Abstract

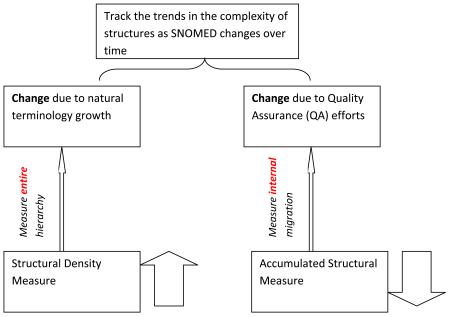

The Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) is an extensive reference terminology with an attendant amount of complexity. It has been updated continuously and revisions have been released semi-annually to meet users’ needs and to reflect the results of quality assurance (QA) activities. Two measures based on structural features are proposed to track the effects of both natural terminology growth and QA activities based on aspects of the complexity of SNOMED CT. These two measures, called the structural density measure and accumulated structural measure, are derived based on two abstraction networks, the area taxonomy and the partial-area taxonomy. The measures derive from attribute relationship distributions and various concept groupings that are associated with the abstraction networks. They are used to track the trends in the complexity of structures as SNOMED CT changes over time. The measures were calculated for consecutive releases of five SNOMED CT hierarchies, including the Specimen hierarchy. The structural density measure shows that natural growth tends to move a hierarchy’s structure toward a more complex state, whereas the accumulated structural measure shows that QA processes tend to move a hierarchy’s structure toward a less complex state. It is also observed that both the structural density and accumulated structural measures are useful tools to track the evolution of an entire SNOMED CT hierarchy and reveal internal concept migration within it.

Keywords: Terminology, SNOMED CT, Complexity Measure, Abstraction Network, Quality Assurance

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

The Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) [1] is a large and complex structure, with its January 2015 release containing about 315,904 concepts organized into 19 hierarchies. Introduced in its original form by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) in 1977, SNOMED CT has been proposed for use as a standard in general encoding in Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems. In 2007, SNOMED CT’s ownership was transferred from CAP to the International Health Terminology Standards Development Organization (IHTSDO).

To meet the needs of users around the world, SNOMED CT has been continuously evolving since its creation via the merger of SNOMED RT and CTV3 [2]. New SNOMED CT releases are published twice a year, in January and July, with each release including refinements to descriptions, enhancements of concept definitions, and additions of new concepts. At the same time, SNOMED CT undergoes a clinical and technical quality assurance (QA) process conducted by IHTSDO’s Quality Assurance Committee [3]. For a review of SNOMED CT users’ views regarding evolution and QA, see [4].

In this paper, we examine the effects of these two kinds of modifications, namely, natural growth and QA, on the complexity of a SNOMED CT hierarchy. Our hypothesis is that, in general, modeling errors (e.g., missing relationships, incorrect parents) contribute to structural disorderliness. The question is: can one expect to see a simplification of the hierarchy structure due to the reduction of such disorderliness after a QA regimen has been carried out? And we would like to ask the same question concerning a natural growth period. Toward this end, we posit a way to assess the complexity of a hierarchy based on previously defined abstraction networks for SNOMED CT. An abstraction network is a framework that, among other things, forms the basis for systematic QA. Specifically, we use the area taxonomy and partial-area taxonomy that are derived via structural analyses of the underlying SNOMED CT hierarchy. In this context, two derived complexity measures are proposed for quantifying the complexity of a hierarchy. One is called the structural density measure; the other is called the accumulated structural measure.

As a test-bed, the measures are applied to the Specimen hierarchy in order to track its changing complexity during the years 2004 to 2013. During that time, we personally carried out two QA processes on the 2004 and 2007 releases. Also, new concepts had been added to the hierarchy due to natural growth in the interim, and their introduction may have indeed led to new errors. Furthermore, both editing and the QA of a hierarchy are difficult tasks, which by themselves are never foolproof. A domain-expert auditor may very well overlook some errors, and the editorial policies may be incomplete or inconsistent. We look for any further impact of this subsequent QA effort on the complexity measures in comparison to the impact of the initial QA audit for the same hierarchy. An initial report of this study appeared in [5]; however, the research further evolved with changes in the definitions of the complexity measures. We also look for the trend of a hierarchy’s complexity due to the natural development of SNOMED CT and the trend due to the mixed impact of both kinds of activities. By tracking the structural density measure over multiple years, we are able to identify when intensive QA activities have taken place. While our focus is on the Specimen hierarchy, we also analyze changes in complexities involving four other hierarchies with the use of the structural density measure.

2 Background

2.1 Area Taxonomy and Partial-area Taxonomy

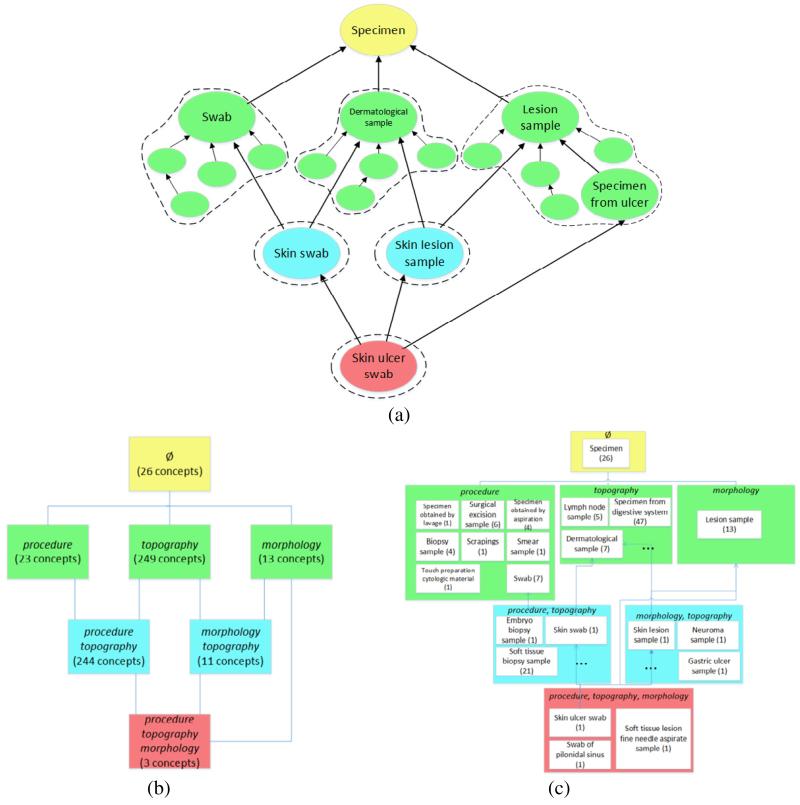

The area taxonomy and the partial-area taxonomy [6, 7] of a SNOMED CT hierarchy are derived automatically from the respective lateral (i.e., non-IS-A) relationships exhibited by the concepts. The partial-area taxonomy also relies on local configurations of the IS-A hierarchy itself. Both taxonomies are based on the notion of area, a collection of all concepts with the exact same set of relationships. Such a collection is denoted by its respective list of relationships (inside braces). For example, in Figure 1(a), showing concepts from Specimen, Lesion sample and its child Specimen from ulcer have only one relationship morphology (not displayed). Thus, they are grouped into the area {morphology}. Swab has only one relationship procedure and thus is in the area {procedure}. Skin swab belongs to the area {topography, procedure} due to it exhibiting those two relationships.

Figure 1.

(a) Concepts from SNOMED CT’s Specimen hierarchy (arrows are IS-As; colors denote numbers of lateral relationships for each concept: yellow = 0, green = 1, blue = 2, red = 3); (b) Excerpt of area taxonomy corresponding to Figure 1(a) (a box is an area; again, colors denote numbers of relationships); (c) Excerpt of partial-area taxonomy corresponding to Figure 1(a)

An area taxonomy is a graph structure that consists of only the areas represented (as nodes) and hierarchical child-of relationships connecting them. A portion of the area taxonomy for SNOMED CT’s Specimen hierarchy corresponding to Figure 1(a) is shown in Figure 1(b). The area at the top is on Level 0 (equal to its number of relationships) and is named Ø for the empty set of its relationships. It contains all concepts with no relationships. The dashed bubbles in Figure 1(a), below the level of Specimen, denote area membership in Figure 1(b). The number of concepts in each area appears in parentheses under the name.

A root of an area is a concept, of that area, whose parents all reside in other areas. An area may have more than one root. The child-of relationships—the arrows in the figure—are derived from the IS-As of the roots as described in [6].

The partial-area taxonomy extends the area taxonomy by further refining areas with multiple roots. In addition to areas, the partial-area taxonomy includes partial-areas, each being a set of concepts comprising a single root and all its descendants within one area. Figure 1(c) is the portion of the Specimen hierarchy’s partial-area taxonomy refining Figure 1(b). The nodes representing the partial-areas are embedded in the respective area nodes. A partial-area’s label is its constituent root, which hierarchically sits atop (and thus subsumes) all other concepts in the partial-area. For example, partial-area Swab has that concept plus its six descendants in the area {procedure}. Note that while the root concepts name the partial-areas, the names of the non-root concepts are hidden. We observe that in the area {procedure}, eight partial-areas are shown in Figure 1(c), e.g., Biopsy sample, Smear sample, and Swab. The number in parentheses alongside a partial-area name indicates its number of concepts. For example, in the area {procedure}, we see partial-area Biopsy sample (4) whose other three non-root (hidden) concepts are Specimen from unspecified body site obtained by biopsy, Specimen obtained by fine needle aspiration procedure, and Specimen from unspecified body site obtained by fine needle aspiration, which is a child of the previous two children of the root.

The child-of relationships in the partial-area taxonomy are defined between partial-areas and are derived from the IS-As directed from the roots, similarly to those in the area taxonomy. To minimize the number of arrows, we use graphical abbreviations described in [6].

In [8], it was shown that concepts residing in more than one partial-area (“overlapping” concepts) have a higher likelihood of being in error than other concepts. Thus, they were chosen as a basis for a QA regimen. Furthermore, in [8], we introduced the disjoint partial-area taxonomy in which such overlapping concepts are extracted to form special partial-areas of their own.

2.2 Previous attempts on SNOMED CT complexity measures

The issue we are investigating is how to assess the complexity of a SNOMED CT hierarchy. In particular, we are interested in studying how complexity measures reflect on the evolution of a given hierarchy over multiple releases as a result of QA regimens and natural development of that hierarchy. One natural criterion is a global weighting function for a hierarchy such as size (the number of concepts) or height (number of levels in the longest hierarchical path). Indeed, in a comparison of such measures following our first audit of the Specimen hierarchy in the 2004 SNOMED CT release, the number of concepts was reduced from 1,056 to 1,044 (July 2005 release), and the height was reduced from 12 to ten. At the same time, SNOMED CT’s total concepts went up from 357,134 to 364,461. Furthermore, only two hierarchies of SNOMED CT decreased in size during this period, the second of which was the huge Clinical Finding hierarchy obtained by integrating the two hierarchies Finding and Disorder. We attribute the decrease in the size of the Specimen hierarchy, which went against the general trend of growth in SNOMED CT during the same period, to the correction of duplicate concept errors (such as Ear sample and Specimen from ear) and the removal of improper concepts due to our QA efforts [6, 7]. The former were caused by the failure to identify the synonymy of “sample” and “specimen” when integrating SNOMED RT and CTV3 into SNOMED CT [9]. The errors we found were reported to CAP and were corrected in future releases. The reduction in height can be attributed to finding errors in some of the most complex concepts in the hierarchy, which participated in the longest hierarchical paths.

However, these measures are more magnitude measures than complexity measures. The size measure accounts only for limited QA impacts such as erroneous concepts eliminated from the hierarchy, but not for other errors that were corrected. The size is also influenced by concepts added to the hierarchy as part of normal expansion. The height measure reflects only QA on a few concepts in the longest hierarchical path. Furthermore, such global measures fail to take into account the role of lateral relationships in the complexity of the concepts. For example, a hierarchy may keep its size and height while going through a QA process, which may make it simpler or more complex.

To illustrate the difficulty of using the size measure, note that the Specimen hierarchy grew from 1,044 concepts in July 2005 to 1,052 in January 2007, while no special QA was done. Finally, the number grew to 1,056 (the original number in 2004) in July of 2007, before a second QA effort was applied. Having two releases (2004 and 2007) of the same size does not necessarily imply that they are of the same complexity.

A complexity measure of a terminological system should reflect its level of difficulty of use and maintenance. The measure should be based on underlying quantifiable system characteristics that are expected to be higher when the ability to perform such activities (including navigation, concept updates, etc.) becomes more difficult. We will restrict the range of complexity measure values to [0, 1]. Let us note that others sometimes use expanded ranges, e.g., [0, 2000] (as is done in [10]).

3 Methods

In the following, we present a basic structural complexity function along with two derived measures: the structural density measure and the accumulated structural measure. The measures are based on lateral relationship (just “relationship,” for short) distributions and various concept groupings that are associated with the abstraction networks. The structural density measure is used to help track changes in the overall complexity of a hierarchy as it evolves over time. The accumulated complexity measure is used to reflect the internal transitions of a hierarchy over time. In general, we are interested in investigating a potential usage of complexity measures as an instrument to observe the evolution of a SNOMED CT hierarchy and track the trend of SNOMED CT terminology development.

3.1 Structural Complexity Measure

We assert that a concept C with two given relationships is more complex than a parent concept P exhibiting only one of those relationships, since concept C with multiple relationships expresses more detailed knowledge than concept P. Similarly, we assert that a concept C with three given relationships is more complex than a parent concept having two out of the three relationships.

For example, as is seen from Figure 1(a) and Figure 1(c), the concept Skin swab in the area {procedure, morphology} has a parent Swab in the {procedure} area, and another parent Dermatological sample in the {morphology} area. In this case, Skin swab is the specialization of the two parents. From the complexity point of view, it is more complex as compared to either one of its parents because it has the extra knowledge expressed by the relationship inherited from the other parent.

Similarly, a root concept Skin ulcer swab in the area {morphology, topography, procedure} (see Figure 1(a) and Figure 1(c)) has three parents in three separate areas. One parent Skin swab, with two relationships, was mentioned above. Another parent Skin lesion sample, with two relationships, is from {morphology, topography}. A third parent Specimen from ulcer, with the one relationship morphology, is a non-root concept in the partial-area Lesion sample in {morphology}. The concept Skin ulcer swab is more complex than the one-relationship parent Specimen from ulcer. It is also more complex than each of the two parents with two relationships.

The higher complexity when comparing a descendant concept to its ancestor is obvious. In general, we measure structural complexity of a concept by the number of its relationships, since as mentioned, the structure of a concept is its set of relationships. In the context of the area taxonomy: a concept on a lower-numbered level is simpler than a concept on a higher-numbered level. This assumption is called the structural assumption, since it is based on a structural feature of the area taxonomy. In measuring structural complexity by the number of relationships, independent of their kind, we extend the notion of higher structural complexity from the case of comparing a child concept to its parent concept to the case of comparing any pair of concepts, where the first has more relationships than the second. The justification for this generalization is that, even in the first case, the reason for the higher complexity of the child is its extra relationship. The area levels of the area taxonomy serve to partition the concepts of the hierarchy according to their numbers of relationships, and thus partitioning the concepts according to their structural complexity. If, as a result of a QA phase, we see an increase in the number of concepts in a lower-numbered area level of a hierarchy at the expense of a decrease in the number of concepts in a higher-numbered area level, then this change can be interpreted as a simplification of the hierarchy structure. Such a change may occur when discovering an unnecessary relationship for a group of concepts. Of course, a concept must first be modeled with all its necessary relationships. A simpler representation of a concept is seen as a desired quality in the modeling of a terminology, but is only secondary to correctness. Hence, the QA process should not seek to delete required relationships just for the sake of simplification. However, as a result of QA, where relationships of concepts are removed or added, we expect to see changes in the structural complexity.

Hence, we are looking for a complexity measure that will enable the comparison of two states of the same SNOMED CT hierarchy as it evolves over time. We are interested in a measure that reflects the number of concepts in the various levels and the changes to those numbers due to the migration of concepts from one level to another (as their relationships change) as a result, for example, of QA. This is different from, say, a global complexity measure that just reflects the total number of relationships in a hierarchy and their partition into levels. Such a related measure is of course also important and will be introduced later.

To formalize this measure, we defined the structural complexity function S(x, H), which is a function from the non-negative integers and a hierarchy to the number of concepts with the corresponding number of relationships, where x represents a level and H is a hierarchy. That is, S(x, H) is the number of concepts on Level x of the area taxonomy of hierarchy H. When there is no ambiguity regarding H, we will often omit it. For a given hierarchy of Levels 0, 1, 2, …, m, we often write the sequence (S(0), S(1),…, S(m)). The function S is a structural measure as it depends solely on the number of relationships, not on their kind. It is a global structural measure for the complexity of the hierarchy because it is dependent on all concepts and their respective structure. To interpret the structural complexity: if more concepts lose relationships than gain relationships, then in the area taxonomy, there is an increase in the number of concepts in lower-numbered levels and a decrease in the number of concepts in higher-numbered levels. In this case, we say that the complexity function is going through a downward weight-shifting towards the lower-numbered levels; we say that the structural complexity is reduced.

3.2 Structural Density Measure

To measure the complexity of an entire hierarchy, we define the Structural Density Measure SD, which is a complexity measure with respect to the average number of relationships per concept (AVGrel) as follows:

where m is the highest level in H. The interpretation of SD(H) is as follows: if the average number of relationships per concept decreases, then SD(H) also decreases and it implies a simplification of the structure; otherwise, it implies an increase in the structural complexity. Hence, when the structural complexity function goes through a downward weight-shifting, SD(H) also decreases. We see that in the rare case where the average number of relationships AVGrel is less than 1, we define SD(H) = 0 to ensure 0 ≤ SD(H) ≤ 1.

3.3 Accumulated Structural Measure

The structural density measure is still not completely satisfying since it fails to reflect the impact of concepts’ migrations from one level to another when the hierarchy is transformed from one state to the next. For instance, there was a large increase in the number of concepts on Level 1 for the July 2007 SNOMED CT. A reason for this phenomenon was a “weight shifting” from the higher-numbered Level 3 towards the lower-numbered Level 1. The condition where one element of (S(0), S(1),…, S(m)) increases while another element decreases does not communicate the decrease in structural complexity that took place. To reflect the above described downward weight-shifting phenomenon, an accumulated structural measure is desirable, which not only measures the changes in the number of concepts at the different levels but also reflects the direction of the migration.

We would like to define a structural complexity measure that will enable a comparison of two states of the same SNOMED CT hierarchy and express the situation where a hierarchy in one state is more complex than in another. Consider, for example, a downward weight-shifting transformation that occurs when, say, 20 concepts on Level 2 in a hierarchy H at time t (denoted Ht) have lost one relationship at the state t+1. In such a case, the total number of concepts in Ht and in Ht+1 is equal, and we would consider Ht+1 to be structurally less complex. However, the structural complexity function S does not express this fact. To illustrate this, assume that Ht has five levels with 50 concepts each. Then the S sequence for Ht is (50, 50, 50, 50, 50), and it is (50, 70, 30, 50, 50) for Ht+1. By comparing these sequences, it is not possible to judge which is more complex since S(1, Ht+1) > S(1, Ht), but S(2, Ht+1) < S(2, Ht) (while all other components are equal).

To achieve our purpose of defining a structural complexity measure that can quantify that Ht+1 is less complex than Ht, we define the Accumulated Structural Measure function Sc from S as follows:

And for j = 1, …, m

In sequence notation with respect to all levels, we get (50, 100, 150, 200, 250) for Ht from Sc and (50, 120, 150, 200, 250) for Ht+1. In this case, Sc(1, Ht+1) > Sc(1, Ht), while all other components are equal.

In general, for two hierarchy states Ht and Ht+1 of the same total number of concepts, and with m levels, we say Ht+1 dominates Ht if

-

(1)

There exists p (0 ≤p<m) such that ∀ i, p ≤ i ≤ m, Sc(i, Ht+1) ≥ Sc(i, Ht).

and

-

(2)

There exist j and k such that ∀ i, j ≤ i ≤ k, Sc(i, Ht+1) > Sc(i, Ht).

According to condition (1), Sc(i, Ht+1) ≥ Sc(i, Ht) is only required beyond the Level p. Condition (2) states that there exists an interval of (k − j + 1) levels above p reflecting an overall downward weight-shifting transformation from Ht to Ht+1.

When Ht+1 dominates Ht, we say that the hierarchy state Ht is structurally more complex than the hierarchy state Ht+1. Such a transformation may involve a simple downward weight-shifting between two consecutive levels, as in the example above, or it may involve more complex transformations. For example, some concepts in Level 2 might lose one relationship while fewer concepts in Level 1 gain one relationship, so that the net change is a downward weight-shifting. Other more complex transformations may involve more than two levels, e.g., a net downward weight-shifting from Level 2 to Level 1, a net downward weight-shifting from Level 3 to Level 1, and a net downward weight-shifting from Level 3 to Level 2. For such a combination of two or three downward weight-shiftings, there will be an interval [1, 2] of indices such that Sc(i, Ht+1) > Sc(i, Ht), for 1 ≤ i ≤ 2. (Note that in such a case, Sc(3, Ht) = Sc(3, Ht+1), due to the accumulative nature of Sc.)

Now let us illustrate the domination between two actual states of the Specimen hierarchy for the July 2007 release and the July 2013 release of SNOMED CT. Table 1 shows the structural complexity function S for the Specimen Hierarchy of July 2004 and July 2007, a duration when our QA efforts [6, 7] took place. Comparing the values, we see that S is larger for Levels 1 and 2 in 2007, while in 2004, it is larger for Levels 0, 3, and 4. Thus, one cannot conclude which hierarchy state is more complex.

Table 1. Structural complexity function for Specimen Hierarchy (2004 vs. 2007).

| Level(l) | # Concepts (2004) | #Concepts (2007) |

|---|---|---|

| S(l) | S(l) | |

| 0 | 29 | 21 |

| 1 | 399 | 468 |

| 2 | 430 | 517 |

| 3 | 194 | 48 |

| 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Total: | 1,056 | 1,056 |

Table 2 shows a similar comparison for Sc. Here, we see a clear domination of the hierarchy for 2007 over 2004, implying that the Specimen hierarchy of 2007 is structurally simpler. Hence, in this case, the QA effort helped to turn the Specimen hierarchy into a structurally simpler hierarchy.

Table 2. Accumulated structural measure for Specimen Hierarchy (2004 vs. 2007).

| Level(l) | # Concepts (2004) | #Concepts (2007) |

|---|---|---|

| Sc(l) | Sc(l) | |

| 0 | 29 | 21 |

| 1 | 428 | 489 |

| 2 | 858 | 1006 |

| 3 | 1052 | 1054 |

| 4 | 1056 | 1056 |

| Total: | 1,056 | 1,056 |

We note that in case Ht+1 dominates Ht, Ht+1 will also have a lower structural density measure since the denominator is decreased in Ht+1 while the numerator does not change. For example, SD(H) for the Specimen hierarchy was decreased from 1 – 1056/1827 = 0.422 in 2004 to 1 – 1056/1654 = 0.362 in 2007.

The conditions (1) and (2) are given for the case where the total number of concepts in Ht+1 is equal to that in Ht. In case the number of concepts in Ht+1 is smaller or larger than in Ht, a scaling will be needed to bring the number of concepts in line to enable a comparison. Note that we are using scaling as a form of normalization in order to maintain the measures in units of concept counts. For the scaling, we look at the percentage of the number of concepts in each level. The scaling is illustrated with the July 2013 release of 1,431 concepts, to be compared with the July 2007 release of 1,056 concepts. Table 3 shows the computation involved in the scaling.

Table 3. Scaling for the 2013 Specimen Hierarchy.

| Level | # on Level | % of Level | Proportional level reduction | Scaled # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 29 | 2 | 8 | 22 |

| 1 | 426 | 30 | 113 | 313 |

| 2 | 624 | 44 | 165 | 459 |

| 3 | 340 | 24 | 90 | 250 |

| 4 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Total | 1,431 | 100 | 375 | 1,056 |

The percentage of the levels appears in column 3. The level difference (up or down) between the number of concepts in the two hierarchy states is distributed between the levels according to their percentages. Column 4 shows the proportional distribution of the 375 (= 1431 – 1056) concepts among the levels. For example, the number at Level 1 is 113 (=375*30%). The number of concepts in the new hierarchy state is modified (up or down) according to the level differences to yield a proportional distribution of the number of concepts in hierarchy state Ht, according to the level percentages of hierarchy state Ht+1. The last column of Table 3 shows the scaled level numbers obtained in reducing the size of Ht+1 (1,431) into the size of Ht (1,056). For example, before scaling the actual number of concepts on Level 1 (July 2013) is 426, which is 30% of the 1,431 concepts; after scaling the number of concepts at Level 1 becomes 313, which is also 30% but with respect to the scaled-down total of 1,056 concepts. The scaling enables a fair comparison of the cumulative structural complexity functions of two hierarchy states of different sizes to check for possible domination.

4 Results

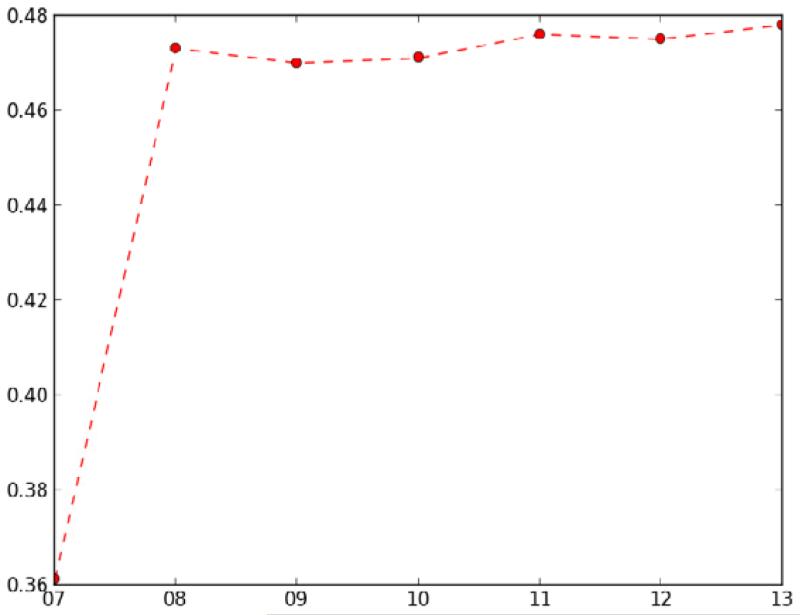

4.1 Using the Structural Density Measure to Track Natural Terminology Growth

We applied the complexity measures to compare the state of the Specimen hierarchy over a long period of time, irrespective of any QA. In particular, we compared the versions from July 2007 to that of July 2013, which is presented in Figure 2. During that seven-year interval, the number of concepts grew from 1,056 to 1,431, while the number of relationships grew from 1,654 to 2,742 (with the average number of relationships per concept growing from 1.75 to 1.91). This growth is reflected by the structural density measure, which increased from 0.361 to 0.478.

Figure 2.

Structural density measure for Specimen hierarchy over seven years of releases

We also compared the structural density measure across different hierarchies in SNOMED CT for the July 2013 release, which is shown in Table 4. According to the definition of the structural density measure, the larger the value, the more complex the hierarchy. By looking at the value, we can get a preliminary idea about the make-up of a hierarchy. If two values are relatively close, then it would not be justified in deeming one hierarchy more complex than the other. However, a clear difference allows us to make an initial judgment about which hierarchy is more complex. For example, as demonstrated in the table, the Situation hierarchy is structurally more complex than the Pharmaceutical hierarchy, since the structural density measures for Situation and Pharmaceutical hierarchies are 0.679 and 0.365, respectively.

Table 4. Structural density measures for five SNOMED hierarchies for July 2013.

| Hierarchy (H) | # Concepts | Avg. # Rels | SA(H) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | 6,209 | 3.118 | 0.679 |

| Pharmaceutical | 17,146 | 1.576 | 0.365 |

| Procedure | 56,358 | 2.392 | 0.582 |

| Specimen | 1,431 | 1.916 | 0.478 |

| Clinical Finding | 99,230 | 1.805 | 0.446 |

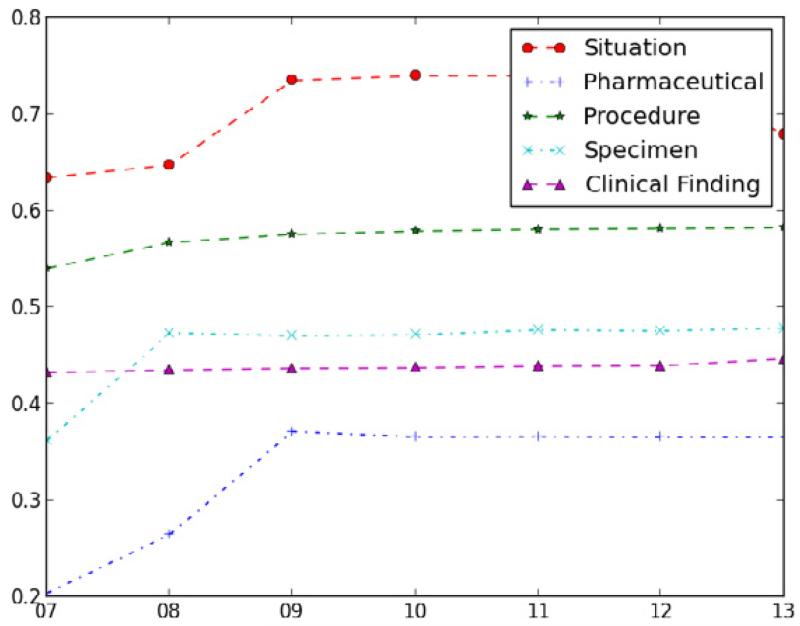

Additionally, we applied the structural density measures to the above five hierarchies to track the natural development of those hierarchies over multiple years’ development, which is shown in Figure 3. As shown in the figure, in general, all five hierarchies demonstrate a trend of increasing complexity over the seven years. Some of the hierarchies, such as Situation, Specimen, and Pharmaceutical, present “inflection points” at some specific year.1 This phenomenon will be discussed below.

Figure 3.

Structural density measures for Situation, Pharmaceutical, Prodcedure, Specimen, and Clinical Finding hierarchies over seven years.

4.2 Using the Accumulated Structural Measure to Track Concept Migrations within a Hierarchy

To obtain the more detailed picture about what happened at the various levels, it helps to compare the structural complexity measure and accumulated structural measure for the two releases. (As discussed, scaling down is used for the July 2013 release due to its greater number of concepts (see Table 3)).

The values of the structural complexity and the accumulated structural measure are given in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. In Level 1, there were 313 concepts (after scaling) in July 2013 in comparison to 399 in July 2004. As shown in Table 6, the accumulated structural complexity values for Level 1 were 335 and 428, respectively. The main change in the structural complexity is due to the growth of Level 3 at the expense of Level 1. When considering the absolute number of relationships, growth occurred in all levels except Level 0, but it was highest for Level 3 and also meaningful for Level 2. From Table 6, we see that H2004 dominates H2013 for all levels. Hence, H2013 is structurally more complex.

Table 5. Structural Complexity Measure (2004, 2013).

| Level (i) | S(i, H2004) | S(i, H2013) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 29 | 22 |

| 1 | 399 | 313 |

| 2 | 430 | 459 |

| 3 | 194 | 250 |

| 4 | 4 | 12 |

| Total: | 1,056 | 1,056 |

Table 6. Accumulated Structural Measure (2004, 2013).

| Level (i) | SC(i, H2004) | SC(i, H2013) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 29 | 22 |

| 1 | 428 | 335 |

| 2 | 858 | 794 |

| 3 | 1052 | 1044 |

| 4 | 1056 | 1056 |

Two QA efforts were conducted on SNOMED CT’s Specimen hierarchy. In the first, various QA techniques were applied to the July 2004 release. The techniques and results were documented in [6, 7]. The July 2007 release reflects the correction of the discovered errors. The second QA process, comprising three separate efforts, took place on the 2007 Specimen hierarchy. During the first effort, all partial-areas of one concept (singletons) were reviewed. In the second and third efforts, all overlapping concepts of partial-areas and a set of non-overlapping concepts of a control sample, respectively, were reviewed. These efforts were reported in [8, 11]. As with the audit on the 2004 version, corrections of errors that were found in all three efforts for the 2007 release are reflected in the July 2008 release.

To assess the impact of the first QA effort on the complexity of the Specimen hierarchy, we will compare the complexity measures for 2004 and 2007. Similarly, to assess the impact of the second QA effort, we will compare the complexity measures for 2007 and 2008. For convenience, we will refer to the states of the Specimen hierarchy as H1 for 2004, H2 for 2007, and H3 for 2008.

Table 7 compares the number of concepts of all different levels for the three states of the Specimen hierarchy. For example, on Level 1 and Level 2, the values of the structural complexity function S(1, H2) and S(2, H2) reflect a large increase for concepts with one and two relationships in 2007, representing many more concepts with lower structural complexity as compared to 2004. The increase for Levels 1 and 2 is from 399 and 430 in 2004 to 468 and 517 in 2007, respectively. These increases are balanced by the decrease in concepts on Level 3 from 194 in 2004 to 48 in 2007. The total number of concepts of H1 and H2 is the same, following the initial decrease and subsequent increase due to changes in intermediate states as reported earlier. So the total number of concepts of H1 and H2 is equal by coincidence.

Table 7. Structural Complexity Measures S(i, H) for 2004, 2007, and 2008.

| Level (i) | S(i, H1) | S(i, H2) | S(i, H3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 29 | 21 | 18 |

| 1 | 399 | 468 | 357 |

| 2 | 430 | 517 | 405 |

| 3 | 194 | 48 | 264 |

| 4 | 4 | 2 | 12 |

| Total: | 1,056 | 1,056 | 1,056 |

Interestingly, the picture is reversed when comparing H2 and H3. A large decrease occurs for Levels 1 and 2, balanced by an increase in Levels 3 and 4. Note that the number of concepts in the Specimen hierarchy in 2008 was actually 1,173, and the 1,056 total listed for H3 in Table 7 reflects the scaling operation (see Section 3) as reported in Table 3.

We note that the decreases in S(1, H3) and S(2, H3) in 2008 from the corresponding numbers in 2007 are not as sharp as they seem from Table 8, which shows the scaled-down numbers. The actual S(1, H3) = 397 and S(2, H3) = 450 (see Table 3) still reflect a decrease versus H2, but are in line with S(1, H1) = 399 and S(2, H1) = 430.

Table 8. Accumulated Structural Measure for 2004, 2007, and 2008.

| Level (i) | SC(i, H1) | SC(i, H2) | SC(i, H3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 29 | 21 | 19 |

| 1 | 428 | 489 | 378 |

| 2 | 858 | 1,006 | 755 |

| 3 | 1,052 | 1,054 | 1,046 |

| 4 | 1,056 | 1,056 | 1,056 |

Table 8 shows the accumulated structural measures SC for H1, H2, and H3. As already shown in Section 3 above, H2 dominates H1, implying that H2 is a less structurally complex hierarchy state. On the other hand, H2 also dominates H3. Hence, H3 is a more complex hierarchy state than H2. When comparing H1 and H3, we see that H1 dominates and is thus less complex than H3. Hence, H3 is the most structurally complex hierarchy state of these three states for the Specimen hierarchy.

The structural density measures for H1, H2, and H3 is 0.422, 0.362, and 0.474, respectively, again showing H3 is the most structurally complex of the three states.

5 Discussion

In this paper, we set out to define complexity measures for a SNOMED CT hierarchy and explore the changes in those measures as the hierarchy goes through QA and experiences natural growth. We introduced one basic structural measure along with two derived aggregates.

5.1 Interpretation

When doing QA work, we eliminate or change incorrect knowledge elements and add missing ones. The idea of a connection of some sort between QA and complexity stems from the possibility that errors in the modeling of concepts cause some disorderliness in the knowledge of a hierarchy. If so, the auditing may help to decrease disorderliness. If disorderliness is expressed by an increase in complexity of a hierarchy, then perhaps QA will be manifested as a decrease in the complexity of the hierarchy.

However, one needs to be aware that complexity also relates to how extensive and involved the knowledge represented in the hierarchy is, and is not necessarily quantifying errors. Hence, the connection between QA and complexity may be subtle, depending on the kind of QA efforts applied, and also on any further development that has taken place in a hierarchy. Furthermore, there may be differences between an initial audit phase and a subsequent audit phase.

As we saw in Section 4, there is a difference in the changes between the two QA periods tracked in this study. The first QA phase yields a decrease in complexity measures of both kinds. First, let us concentrate on the structural density measures. The structural density measure was reduced from 0.422 to 0.362 reflecting a reduction of 203 relationships (from 1,857 to 1,654) between 2004 and 2007. (This count does not include occurrences of multiple targets for the same relationship with respect to the same source concept, which are not reflected in the definition of the structural complexity.) The reduction of 203 erroneous relationships in a hierarchy of 1,056 concepts is a meaningful improvement in both quality and simplicity. The amount of incorrect relationships is even higher than it seems to be if one also considers the relationships that were found to be missing and were subsequently added, since those cancel the impact of the same number of deleted relationships. Obviously, it is imperative that concepts have the correct relationships, even if it makes them more complex. To illustrate such an example, in 2004, the partial-area Specimen from digestive system had an extraneous identity relationship that was subsequently removed from its 38 concepts [6]. This improvement in structural complexity obtained by the movement of concepts from Levels 3 and 4 to Levels 1 and 2 (see Table 7) is properly captured by the accumulated structural measure for which H2 dominates H1 (see Table 8). Hence, as a result of the 2004 QA phase, the Specimen hierarchy became structurally simpler. That is, in parallel to many errors being corrected, the hierarchy’s concepts became less structurally complex. The average number of relationships per concept was reduced from 1.76 to 1.57.

The picture for the second QA phase applied for the 2007 Specimen hierarchy is very different. The structural density measure increased even beyond the original 2004 level. For example, the structural density measure grew to 0.474, 30% higher than in 2004. This increase is well reflected by the accumulative structural measure, where H3 is dominated by both H1 and H2, that is, H3 is more complex than both.

An obvious question is: what is the reason for such a change in the number of relationships between the first QA audit and the second. In 2004, we did not audit overlapping concepts but we audited singletons and other small partial-areas. We discovered so many incorrect relationships that after accounting for the added relationships, we still had a net decrease of 203 relationships.

One possibility is that incorrect relationships, that need to be deleted (i.e., errors of commission), are relatively easier to detect than missing relationships that need to be included (i.e., errors of omission). The erroneous knowledge asserted by incorrect relationships is perhaps sticking out like a sore thumb. These relationships are detectable even on a cursory review. On the other hand, to detect a missing relationship, one has to absorb all the existing knowledge and then surmise that some is missing, which can be a much more demanding mental task. Hence, we assume that almost all incorrect relationships were discovered in the 2004 audit, while only a portion of the missing relationships were uncovered and added in that initial QA phase. Also, we see that a net of 117 concepts were added to the Specimen hierarchy during this period, which we attribute to the routine developmental work done by CAP (which maintained SNOMED CT at the time). In summary, the period of 2007–2008 was not a period of just QA activity but one of combined development and auditing. Hence, it is difficult to isolate the impact of QA itself on the complexity.

Another interesting phenomenon is manifested by tracking the structural density measure over seven years’ releases for five SNOMED CT hierarchies (Specimen, Situation, Pharmaceutical, Procedure, and Clinical Finding) as shown in Figure 3. “Inflection points” can be seen in the Pharmaceutical, Specimen, and Situation hierarchies, all of which experienced QA processes during the measurement period. For example, QA took place in 2009–2010 to improve the Pharmaceutical hierarchy in its use in delivering better health care to people and support the representation of drugs, with a perspective closer to patients. This QA process was documented in IHTSDO’s Collaborative WorkSpace [12, 13]. Before this QA, the structural density measure increased due to the fact that 174 new concepts were added to the higher-numbered levels in the Pharmaceutical hierarchy. On the other hand, the QA process eliminated some unnecessary relationships, and thus it showed a declining trend afterwards. The Specimen hierarchy also shows an inflection point during the years 2007–2008 due to QA, which was discussed above.

5.2 Comparison with Existing Complexity Measures

Some existing complexity measures, mainly based on the quantity, ratio, and correlation of concepts and relationships, have been used to evaluate ontologies, particularly from the viewpoint of evolution [14, 15]. In [10], a simple cognitive complexity model was introduced to determine the cognitive complexity of justifications for entailments of OWL ontologies.

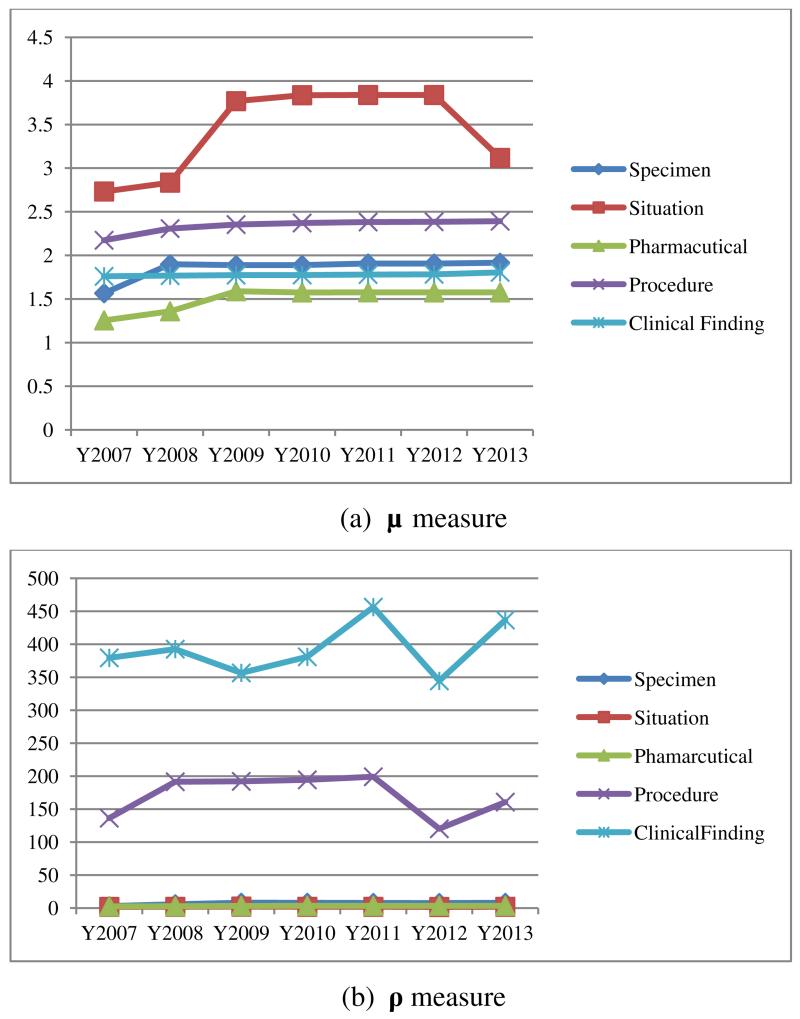

We compared our measures with the μ values and ρ values mentioned in [14, 15]. Our proposed structural density measure focuses on relationship density, and similarly μ measures average relationships per concept. So when tracking the evolutions of the SNOMED CT hierarchies analyzed herein using both measures, the trends are observed to be consistent (see Figure 3 and Figure 4(a)). However, when we compare the evolutions of structural density measure with ρ, the average paths per concept (see Figure 3 and Figure 4(b)), we find that the trends tend to be varied depending on the particular hierarchy. For the Pharmaceutical hierarchy, the trends are consistent with a stable increase over the seven years. For some hierarchies, such as Procedure, the trend for the structural density measure shows a stable increase whereas the trend for the ρ measure shows an initial increase during the years 2007–2008 and later decreases during 2011–2012. This difference is due to the fact that the structural density measure and ρ focus on different aspects. The latter focuses on definitional relationship density, while the former focuses on hierarchical relationship density. None of the existing complexity measures can reflect internal migration within a hierarchy as does our proposed accumulated structural measure.

Figure 4.

(a) μ measure (b) ρ measure for Situation, Pharmaceutical, Procedure, Specimen, and Clinical Finding hierarchies over seven years

5.3 Limitations and Future Work

In this paper, we concentrated on structural aspects of SNOMED CT and their impact on complexity measures as reflected explicitly by the levels of the partial-area taxonomy. However, as an abstraction network [16], the PAT has hierarchical semantic clustering aspects in addition to its structural aspects. The duality is manifested by the areas for the structural features and the partial-areas for the hierarchical clustering features. In the future, we are going to concentrate on introducing complexity measures that factor in the hierarchical clustering.

In this work, we have shown that the Specimen hierarchy of SNOMED CT became simpler according to our complexity measures due to an initial QA effort. The situation for a subsequent QA effort was a mixed result due to several issues discussed above. More experiments with other hierarchies of SNOMED CT or similar terminologies (e.g., NCIt) are needed to further study the connection between complexity and the impact of QA on a hierarchy of a DL-based terminology [17-19] such as SNOMED CT. In particular, in [20], QA was performed on the “bleeding” subhierarchy of Clinical Finding with a focus on its overlapping concepts. That work provides perspective on the impact of QA on overlapping concepts in another hierarchy.

A major limitation of our suggested complexity measures is that they are not applicable to SNOMED CT hierarchies without outgoing relationships. Eleven out of the 19 hierarchies (e.g., the Physical Object hierarchy) fall into this category. The concepts of these hierarchies just serve as targets for the relationships from other hierarchies. Thus, the area taxonomy and the partial-area taxonomy are not defined for them. (In [21], we introduced the “converse abstraction network” to handle such hierarchies.) Hence, neither of the two complexity measures is applicable. It is a research problem to identify what aspects of such a hierarchy need to be reflected in a complexity measure. The recently introduced Tribal Abstraction Networks for such SNOMED CT hierarchies [22] may point to an interesting direction.

A particular problem we encountered was in reporting the complexity measure for the period 2007–2008, during which time the Specimen hierarchy went through three separate audits and, evidently, regular content development performed by CAP. We note that, potentially, these two activities may influence changes in the complexity measures in different ways. A future research problem is to investigate the impact of content development on complexity measures of a hierarchy. We expect a different impact from that of QA due to several factors. We also expect different impacts in early development stages versus later stages. For example, in early stages, new concepts are expected to be less complex (with few relationships), while in later stages, many simple concepts are already in the hierarchy and typically more complex concepts (with relatively more relationships) are added. Also, in earlier stages, many new concepts are expected to be roots of new partial-areas, while in later stages concepts are mostly joining existing partial-areas. Such phenomena will influence the complexity measures differently.

To investigate such phenomena, one has to identify precisely when a hierarchy goes through the different processes. For example, in the SNOMED CT releases of July 2008, July 2009, July 2010, and July 2011, July 2012, and July 2013, we observed the following numbers of concepts in the Specimen hierarchy, respectively: 1,173, 1,236, 1,266, 1,330, 1,331, and 1,431. To our knowledge, there was no QA activity for this hierarchy during this period. Hence, the period from July 2008 through July 2013 represented a time of just content development, for which one could investigate the impact on the complexity measures.

Another interesting research problem is what will happen if a QA effort were to target the new concepts added to the Specimen hierarchy during a phase of content development, as for this period of July 2008 – July 2013. Would we see a decrease in the complexity due to such an audit, as we saw for the initial audit of 2004?

We observed an increase in the structural complexity when comparing the releases of 2013 to that of 2004. This is not unexpected because concepts added later in the hierarchy’s life cycle tend to be more complex and have more relationships, since the simpler ones in the lower-numbered levels already exist. The cohesiveness of the hierarchy tends to improve over time since concepts added later, more often joining existing partial-areas than establishing new ones.

However, this broad range comparison overlooks important facts that were exposed when tracking the impact of QA efforts. For example, the structural complexity declined at first due to the initial 2004 audit, but later increased. These observations support our opinion that more refined analysis is needed to reflect different change patterns for QA versus content development. Furthermore, there are differences between changes occurring during the initial periods of a hierarchy’s cycle and later periods when the hierarchy is in a more mature state. Such differences exist for both QA activity and content development activity.

We had the option of auditing the July 2005 release instead of the July 2007 release. During the July 2004 – July 2005 period, the Specimen hierarchy seemed to have gone strictly through auditing, as reported in [6, 7]. The following two years of release periods showed very slow growth of 12 concepts. We are not sure if these 12 concepts were added as a result of our QA reports or some other QA performed by CAP, or just reflected a slow development process. We decided to use the July 2007 release as both ending the first QA period (of 2004) and starting the second QA period (ending July 2008) for several reasons. First and foremost, the impact of the addition of the 12 concepts seems negligible compared to the major changes that resulted from auditing, as described in Section 4. Second, it was simpler to deal with only three states of the hierarchy, where H2 represented both the end of the first period and the beginning of the second. Otherwise, we would have needed to process the July 2005 version, as the end state for the first QA period, and deal with the increase in size (from 1,044 concepts to 1,056). The third reason was that the coincidence of H2 and H1 having the same number of concepts enabled the direct comparison of the structural complexity measures of 2004 and 2007 without introducing scaling. This simplified the presentation of the results.

6 Conclusion

The structural density measure and the accumulated structural measure were introduced to quantify the complexity of a SNOMED CT hierarchy. They are based, respectively, on characteristics of the area taxonomy and partial-area taxonomy abstraction networks that we previously introduced. Both measures are derived automatically via analysis of structural aspects of the hierarchy.

The suggested measures offer quantitative ways to track a hierarchy’s natural growth and QA efforts by showing the changes over time. In particular, we focused on the changes occurring to the Specimen hierarchy. We also analyzed and compared the changes in four other hierarchies. The structural density measure shows that natural growth moves a hierarchy’s structure toward a more complex state, whereas the accumulated structural measure shows that QA processes tend to move the hierarchy’s structure toward a less complex state. It is also observed that both the structural density and accumulated structural measures are useful tools to track the evolution of an entire hierarchy, and they can also be useful in revealing changes in the complexity within a SNOMED CT hierarchy.

Highlights.

We developed two measures based on structural features to track the effects of both natural terminology growth and quality assurance (QA) activities.

The two measures are called structural density measure and accumulated structural measure.

The structural density measure shows that natural growth tends to move a hierarchy’s structure toward a more complex state, whereas the accumulated structural measure shows that QA processes tend to move a hierarchy’s structure to a less complex state.

Both measures are useful tools to track the evolution of an entire SNOMED CT hierarchy and reveal internal concept migration within it.

Acknowledgment

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01CA190779. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

An inflection point is a point on a curve at which the curve changes from being concave (concave downward) to convex (concave upward), or vice versa.

References

- [1].IHTSDO: International Health Terminology Standards Development Organization Available at www.ihtsdo.org.

- [2].OpenClinical: knowledge mangement for medical care. Available at http://www.openclinical.org/medTermSnomedCT.html.

- [3].IHTSDO Quality Assurance Committee Available at http://www.ihtsdo.org/participate/join-a-committee/quality-assurance-committee.

- [4].Elhanan G, Perl Y, Geller J. A survey of SNOMED CT direct users, 2010: impressions and preferences regarding content and quality. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 18:i36–i44. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wei D, Wang Y, Perl Y, Xu J, Halper M, Spackman KA. Complexity measures to track the evolution of a SNOMED hierarchy; AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings: American Medical Informatics Association; 2008; pp. 778–782. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wang Y, Halper M, Min H, Perl Y, Chen Y, Spackman KA. Structural methodologies for auditing SNOMED. Journal of biomedical informatics. 40:561–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2006.12.003. l2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Halper M, Wang Y, Min H, Chen Y, Hripcsak G, Perl Y, Spackman KA. Analysis of Error Concentrations in SNOMED; AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings: American Medical Informatics Association; 2007; pp. 314–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wang Y, Halper M, Wei D, Perl Y, Geller J. Abstraction of complex concepts with a refined partial-area taxonomy of SNOMED. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2012;45:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Spackman K. Rates of change in a large clinical terminology: three years experience with SNOMED Clinical Terms; AMIA Annual Symposium Proceeding; 2005; pp. 714–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Horridge M, Bail S, Parsia B, Sattler U. The cognitive complexity of OWL justifications; The 10th International Semantic Web Conference, ISWC 2011; Bonn, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2011.pp. 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang Y, Halper M, Wei D, Gu H, Perl Y, Xu J, Elhanan G, Chen Y, Spackman KA, Case JT, Hripcsak G. Auditing complex concepts of SNOMED using a refined hierarchical abstraction network. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2012;45:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Campbell K, Castillo S, Browne E. IHTSDO Workbench Guide: Introduction and Overview. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [13].IHTSDO Collaborative WorkSpace Available at https://csfe.aceworkspace.net/sf/sfmain/do/home.

- [14].Zhe Y, Dalu Z, Chuan Y. Evaluation Metrics for Ontology Complexity and Evolution Analysis; e-Business Engineering, 2006. ICEBE ‘06. IEEE International Conference on; 2006.pp. 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhe Y, Dalu Z, Chuan Y. Ontology analysis on complexity and evolution based on conceptual model. In: Ulf L, Felix N, Barbara E, editors. Data Integration in the Life Sciences. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2006. pp. 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Halper M, Gu H, Perl Y, Ochs C. Abstraction networks for terminologies: Supporting management of “big knowledge”. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. 2015;64:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wei D, Bodenreider O. Using the abstraction network in complement to description logics for quality assurance in biomedical terminologies-a case study in SNOMED CT. Studies in health technology and informatics. 2010;160:1070–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Spackman KA. Normal forms for description logic expressions of clinical concepts in SNOMED RT; Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium; 2001; pp. 627–631. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Schulz S, Markó K, Suntisrivaraporn B. Formal representation of complex SNOMED CT expressions. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2008;8:S9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ochs C, Perl Y, Geller J, Halper M, Gu H, Chen Y, Elhanan G. Scalability of Abstraction-Network-Based Quality Assurance to Large SNOMED Hierarchies; AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings: American Medical Informatics Association; pp. 1071–1080. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wei D, Halper M, Elhanan G, Chen Y, Perl Y, Geller J, Spackman KA. Auditing SNOMED relationships using a converse abstraction network; AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings: American Medical Informatics Association; 2009; pp. 685–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ochs C, Geller J, Perl Y, Chen Y, Agrawal A, Case JT, Hripcsak G. A tribal abstraction network for SNOMED CT target hierarchies without attribute relationships. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 22:628–639. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-003173. l2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]