Abstract

Study Objective

To validate the virtual reality VBLaST-PT (the peg transfer task) for concurrent validity based on its ability to differentiate between novice, intermediate and expert groups of gynecologists, and the gynecologists’ subjective preference between the physical FLS system and the virtual reality system.

Design

Prospective study (Canadian Task Force II-2)

Setting

Academic medical center.

Participants

Obstetrics and gynecology residents (n = 18), and attending gynecologists (n = 9)

Interventions

Twenty-seven subjects were divided into three groups: novices (PGY1-2, n = 9), intermediates (PGY3-4, n = 9), and experts (attendings, n = 9). All subjects performed ten trials of the peg transfer on each simulator. Assessment of laparoscopic performance was based on FLS scoring while a questionnaire was used for subjective evaluation.

Measurements and Main Results

The results show that the performance scores in the two simulators were nearly identical. Experts performed better than intermediates and novices in both the FLS trainer and the VBLAST© and intermediates performed better than novices in both simulators as well. The results also show a significant learning effect on both trainers for all subgroups however the greatest learning effect was in the novice group for both trainers. Subjectively 74% participants preferred the FLS over the VBLaST© for training laparoscopic surgical skills.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the peg transfer task was reproduced well in the VBLaST in gynecologic surgeons and trainee’s. The VBLaST© has the potential to be a valuable tool in laparoscopic training for gynecologic surgeons.

Introduction

Performing minimally invasive surgery requires development and refinement of a select set of psychomotor skills not utilized in traditional open surgical procedures. In obstetrics and gynecology residency and in gynecologic surgical subspecialty training the traditional approach of “see one, do one, teach one” as the cornerstone of teaching trainees to develop safe surgical practice is outdated. Surgical simulation skills arcades and centers have been developed to provide trainees of all levels a safe, non-threatening learning environment. The development and assessment of the necessary laparoscopic psychomotor surgical skills required for safe surgical practice can, in part be undertaken utilizing simulation trainers. A variety of surgical simulation trainers have been developed for use in training and assessing minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons. (1,2,3)

The Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) program was developed by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) as a tool for assessment of basic knowledge and surgical skills necessary for basic laparoscopic surgery. When originally developed, the FLS program was designed to be applicable to all surgical specialists who perform laparoscopy including general surgeons, urologists, thoracic surgeons and gynecologists.(4) The FLS program is comprised of a cognitive examination as well as a manual skills section composed of 5 separate tasks. The skills component has been validated in gynecologists and the FLS program has been incorporated in many Ob/Gyn residency training programs. (5, 6, 7) For surgical residents successful completion of the FLS exam is a requirement before being allowed to take the qualifying Examination of the American Board of Surgery. Perhaps the major drawbacks of the FLS practical, manual skills exam component is the intensity of labor that is required to perform a validated assessment with high inter-rater reliability in a cost-effective fashion. This includes proctor training, test center availability, proctor expense and the cost of supplies that are required to administer and proctor the examination.

The Virtual Basic Laparoscopic Skill Trainer (VBLaST©) (8) is a virtual reality simulator that is being developed to simulate the FLS tasks with funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The VBLaST-PT© is the version that simulates the peg transfer task of the FLS. Unlike other trainers, the VBLaST-PT© system is capable of measuring performance without the need for a proctor or replenishing training and testing materials. The VBLaST-PT© provides realistic haptic feedback which is an essential component of minimally invasive simulators and has undergone face and construct validation in surgical trainees and experts. (9, 10, 11) (12, 13, 14)

The objective of this study was to assess the value of the current VR technology used in the peg transfer task of the VBLaST© based on the subjective preference of the gynecologic surgeons, their objective performance on the simulator and to investigate the ability of the VBLaST-PT© to differentiate between novice, intermediate and expert gynecologists.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty seven (27) subjects (26–45 years old; 2 males, 25 females; 25 right handed, 2 left handed), to include all levels of OB/Gyn residency and attendings, were recruited in this Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved study. They were divided into three groups – novices, intermediates and experts, based on their experience level with 9 subjects in each group as shown on Table 1.

Table 1.

subjects’ expertise levels

| Expertise level | Novices | Intermediates | Experts | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 9 | 9 | 9 | ||

| Post-graduate year | PGY1 | PGY2 | PGY3 | PGY4 | Attendings |

| Number of subjects | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 9 |

The first and second year OB/Gyn residents (PGY1 and PGY2) were included in the “novices” group, third and fourth year OB/Gyn residents (PGY3 and PGY4) were included in the “intermediates”, and the OB/Gyn attendings were included in the “experts” group. All residents were recruited at the beginning of their academic year while the attendings had varying numbers of years of practice (from 0 to 8). First and second year OB/Gyn residents were included in the novice group (Nov) because they had limited laparoscopic experience (most having performed less than 10 laparoscopic cases). Third and fourth year OB/Gyn residents were included in the intermediate group (Int) because of their intermediate laparoscopic experience (most having performed more than 10 but fewer than 50 laparoscopic cases). Attendings were selected in the expert group (Exp) due to their advanced laparoscopic experience, most having performed more than 50 laparoscopic cases.

Apparatus

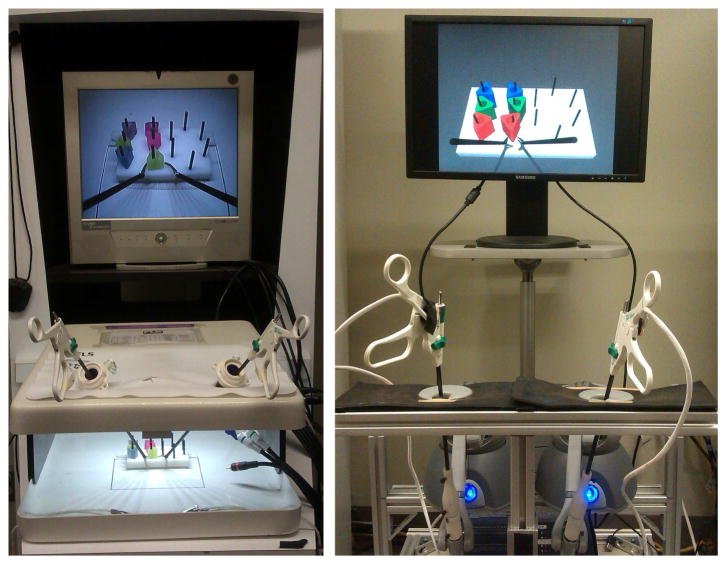

The VBLaST-PT© and the FLS trainers with the peg transfer task, were used for this experiment (Figure 1). The trainers workspace consists of a peg board placed in the center of the box trainer with 12 pegs and six rings. For each trial, the six rings were initially positioned on the left side of the peg board.

Figure 1.

The peg transfer simulators, (Left) the FLS, (Right) the VBLaST-PT©

The VBLaST-PT© is a VR simulation of the FLS trainer workspace connected to a physical user interface. This user interface was built using two laparoscopic graspers connected to two PHANTOM Omni haptic devices (Geomagic Inc., Boston, MA, USA) aiming to transmit force feedback to the users.

One experimenter recorded the participants’ performance (including the completion time and errors) for the FLS trainer, while the performance measures for the VBLaST-PT© were automatically recorded by the system.

Experimental procedure

The peg transfer task is the first of the five standard psychomotor tasks in the FLS curricula. It consists of using two graspers (one in each hand), to pick up one ring at a time with the left hand, transfer it to the right hand, and place it on the right side of the peg board. Once all the six rings were transferred, the users are asked to transferring them back to the left side to complete one trial.

Prior to performing the task, the participants completed a questionnaire detailing the demographics and their previous experiences with laparoscopic procedures and trainers. The participants were then given verbal instructions by one experimenter on how to perform the task. After that, they were asked to perform ten trials of the peg transfer task in the VBLaST-PT© simulator and ten trials in the FLS trainer box. The presentation order of the simulators was counterbalanced meaning that half of the subjects started on the VBLaST-PT© while the other half started on the FLS trainer. At the end of the session, the participants were asked to assess some features of the VBLaST-PT© (visual appearance, haptic feedback, 3D perception, tools movement and overall quality and reliability of the system as a training and assessment tool) using a subjective questionnaire with a 5-point Likert scale (from (1) representing very poor/not satisfactory to (5) representing very good/very satisfactory).

Measurements

A total raw score (ranging from 0 to 300), using a combination of the task completion time and the number of rings dropped outside of the board, was used to assess the users’ performance on each trainer. To obtain comparable scores, the raw scores for both systems were computed using the same formula based on the undisclosed scoring metric (15) obtained from the SAGES FLS committee. Using the conventional method of normalizing data (12, 15), these raw scores were then normalized by dividing them by the best score obtained by one of the experts in each condition (FLS experts’ best score for the FLS condition and VBLaST experts’ best score for the VBLaST condition). The FLS and VBLaST normalized scores ranged from 0 to 100.

Data analysis

The experiment was a 2 (simulators) × 3 (experience levels) mixed design. The Pearson’s correlation test was used to assess the correlation between the FLS scores and the VBLaST scores. Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) with an alpha value of 0.05 were used to evaluate the effect of the simulator and the experience levels on the performance scores and on the gain in scores. The Friedman rank sum test was used to examine the learning effect over the ten trials. A multiple regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between the dependent variables (the performance scores) and the independent variable (the expertise level) for each trainer. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to choose the best-fit linear model. Finally, descriptive statistics were used to analyze the subjective evaluation by calculating the average ratings and their standard errors. The data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Correlation

The Pearson’s correlation test showed that the FLS and VBLaST-PT © mean normalized scores had a correlation of 0.80 (Pearson’s r (25) = 0.80, p < 0.001).

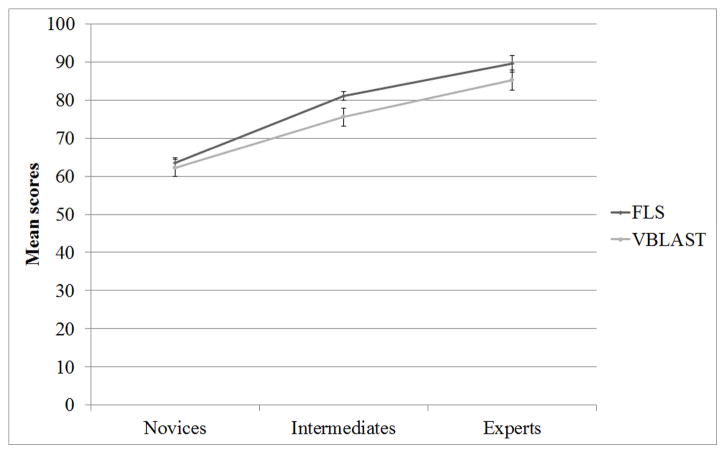

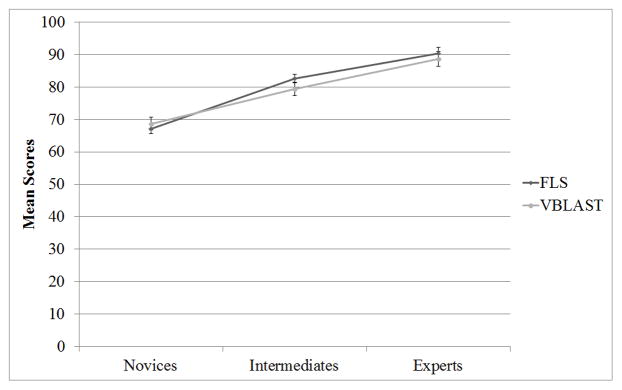

Effect of experience level and simulator

A two-way mixed design (split-plot) ANOVA showed that there is a main effect of simulator (F(1,24) =5.45, p=0.02) and a main effect of the expertise level (F(2,24) = 27.88, p < 0.001) on the performance scores (Figure2). No significant interaction effect was observed (F(2,24) =0.59, p = 0.56).

Figure 2.

Effect of simulator and experience level on performance scores

Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the experts performed better than the intermediates (p = 0.02) and the novices (p < 0.001) in both simulators. Moreover, the intermediates performed better than the novices (p < 0.001) in both simulators.

Linear models

The expertise level significantly predicted the FLS performance score (b = 12.98, t(26) = 7.38, p = 0.01, adjusted R-squared= 0.67). The linear model is:

The expertise level significantly predicted the VBLaST performance score (b = 11.53, t(26) = 5.54, p = 0.01, adjusted R-squared= 0.53). The linear model is:

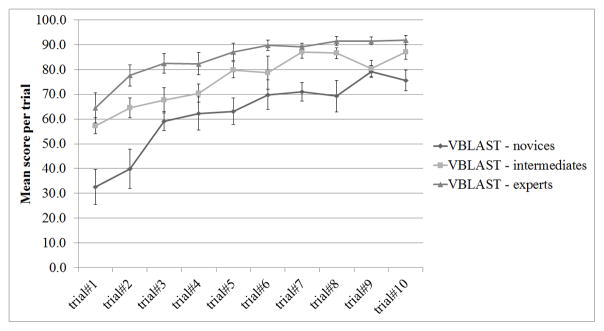

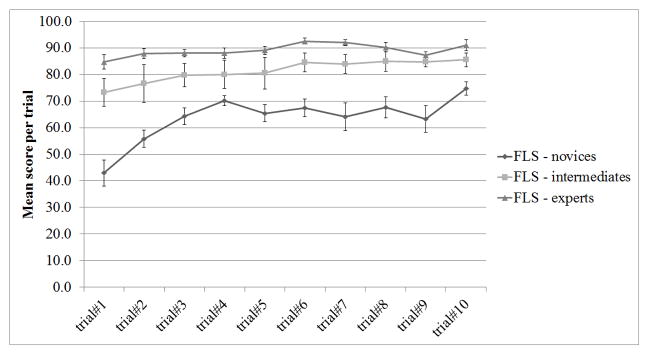

Learning effect

The Friedman rank sum test showed a significant learning effect from trial #1 to trial #10 in both FLS and VBLaST-PT© systems (χ2(9)=47.12, p < 0.000; χ2(9)= 131.22, p < 0.000, respectively; Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Learning effect over 10 trials for the VBLaST performance scores

Figure 4.

Learning effect over 10 trials for the FLS performance scores

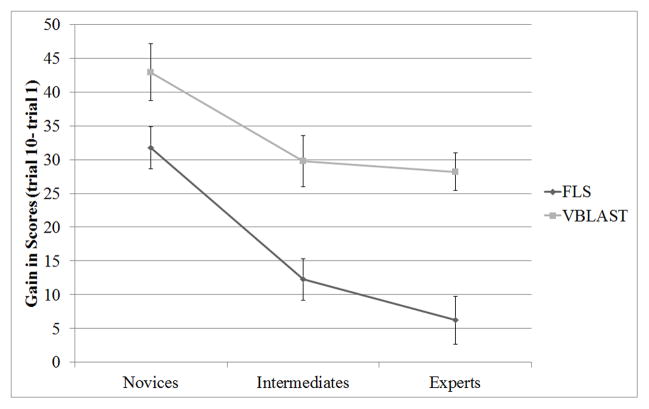

Gain in scores

A two-way mixed design (split-plot) ANOVA showed that there is a main effect of simulator (F(1,24) =27.5, p<0.000) and a main effect of the expertise level (F(2,24) =9.85, p<0.001) on the gain in scores between the first and the last trials (Figure 5). No significant interaction effect was observed (F(2,24) =0.758, p=0.48).

Figure 5.

Mean gain in scores between the first and the last trials

Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the novices improved their performance significantly more than the intermediates (p=0.01) and significantly more than experts (p=0.001). No significant differences on the gain in scores were observed between intermediates and experts.

Comparison over trial 3 to trial 10

In order to eliminate any effect of an adaptation period for the VR technology, the two first trials on each simulator were removed (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of simulator and experience level on the mean performance scores for trials 3 to 10

A two-way mixed design (split-plot) ANOVA showed that there was no main effect of simulator (F(1,24) =1.18, p=0.29) while a significant main effect of the expertise level was found (F(2,24) =22.42, p<0.000). No significant interaction effect was observed (F(2,24) =1.10, p=0.35).

Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the experts performed better than the intermediates (p=0.04) and the novices (p<0.000), and that the intermediates performed better than the novices (p<0.001) in both simulators.

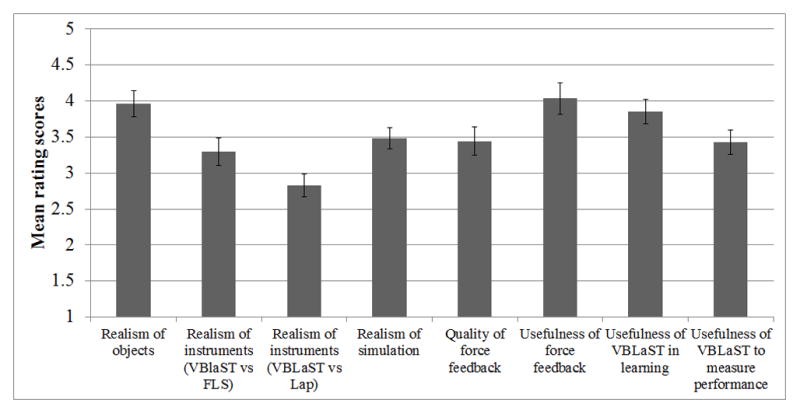

Subjective evaluation

The subjective ratings of the VBLaST-PT© features are shown in Figure 7. The average rating for the usefulness of force feedback (4.05), the realism in rendering (3.96), and the usefulness of the system for learning laparoscopic skills (3.85) were rated the highest. Realism of instrument handling compared to laparoscopic surgery had the lowest rating (2.82). 26% of the subjects preferred using the VBLaST over the FLS trainer for training laparoscopic surgery skills.

Figure 7.

Subjective evaluation of the VBLaST

DISCUSSION

In our study, the VBLaST© peg transfer simulator with haptic feedback compared exceptionally well to the FLS trainer box in gynecologic surgeons and trainee’s. We hypothesized that subjects with more training and experience would perform better than those with less training and experience and better than novices in both systems. The results showed a significant and strong correlation between the VBLaST-PT© and FLS box trainer scores for all levels of experience suggesting that the Peg transfer task was well reproduced in this virtual FLS trainer. Our study also identified a significant learning effect in both the virtual and standard FLS over 10 trials which was inversely proportional to experience (Figures 3, 4). We also noted that there was significant gain in score between the first and last trials in the novice group which was significantly greater than the gains seen in intermediate and expert groups. The mean gains in scores between first and tenth trial were significantly higher in the VBLaST© trials versus the FLS trials in all groups (Figure 5). These results suggest that all participants found the novelty of the VBLaST© system initially a challenge and that an adaptation period to the virtual environment was required. If we consider the first two rounds as an adaptation period for both tasks and measure only trials 3–10, we see nearly identical average scores within each experience group (Figure 6). We believe that this demonstrates that some adaption to the virtual environment is necessary but that following this VBLaST-PT© correctly simulated the FLS peg transfer task.

In order to better understand the potential limitations of the virtual environment our study included a subjective evaluation of various aspects of the VBLaST© system (Figure 7). Our test subjects found the virtual objects realistic and the force feedback useful but they were less impressed with the realism of the instrument handling. While our subjects all rated the VBLaST© system as useful in learning, 74% of the subjects preferred using the FLS trainer for training laparoscopic surgery skills over the VBLaST© system. This may be due to the fact that the FLS trainer box is the traditional tool on which subjects first learned to perform basic skills, and the novelty of computer generated images and videogame-like environment creates unfamiliarity. Subjects may require a period of adaptation to become comfortable with the new interface. We believe that further improvements in the instrument handling including both hardware and software components will bring us closer to the equivalence of the virtual experience of this FLS task.

Several virtual reality trainers have been tested and validated in gynecologic surgeons. Unfortunately these virtual trainers tend to specifically test virtual gynecologic surgical procedures and not skill exercises common to all surgeons. (16,17) Given the high complexity of gynecologic minimally invasive surgical procedures, we expect our graduating residents to be proficient in the same basic surgical skills contained in the FLS curriculum for surgery residents. It is a challenge to justify that they should be held to a different standard than graduating general surgery residents who are required to pass the FLS exam before sitting for their boards. Nationally, if graduating chief obstetrics and gynecology residents were tested in basic laparoscopic proficiency as demonstrated by successful completion of the FLS skills component, we would ensure a base skills standard across surgical specialties. Development of the Virtual Basic Laparoscopic Skills Trainer will eventually include the other four FLS skills tasks. These include virtual ligation loop, pattern cutting, extra and intracorporeal knot tying tasks. Given the results of this validation study and that the original intention for FLS was for the test to be applicable to all surgical specialties, inclusion of gynecologist with general surgeons in our subsequent testing and validation studies of the remaining VBLaST© tasks is now justified.

Ultimately we believe that virtual reality trainers such as the VBLaST-PT© will play an integral role in obstetrics and gynecology residency surgical training. Our study here demonstrates the validation of the VBLaST-PT© in gynecologist and trainees and takes us one step closer to utilizing this exciting technology to provide a solid foundation of laparoscopic skills in our trainees.

Acknowledgments

Funding Information: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant NIBIB RO1EB010037-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Arden D, Hacker MR, Jones DB, Awtrey CS. Description and validation of the Pelv-Sim: a training model designed to simulate gynecologic minimally invasive suturing skills. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(6):707–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tunitski-Bitton AE, King CR, Ridgeway B, Barber MD, et al. Development and Validation of a Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy Simulator Model for Surgical Training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Jan 21; doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.12.124. S1553-4650(14)00031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gala R, Orejuela F, Gerten K, Lockrow E, Kilpatric C, et al. Effect of validated skills simulation on operating room performance in obstetrics and gynecology residents: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Mar;121(3):578–584. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318283578b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters JH, Fried GM, Swanstrom LL, et al. Development and validation of a comprehensive program of education and assessment of the basic fundamentals of laparoscopic skills. Surgery. 2003;135(1):21–27. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng B, Hur H, Johnson S, Swanstrom L. Validity of using Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) program to assess laparoscopic competence for gynecologist. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:152–160. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0539-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hur HC, Arden D, Dodge LE, Zheng B, Ricciotti HA. Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery: A Surgical Skills Assessment Tool in Gynecology. JSLS. 2011;15:21–26. doi: 10.4293/108680810X12924466009122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antosh DD, Auguste T, George EA, Sokol AI, et al. Blinded assessment of operative performance after fundamentals of laparscopic surgery in gynecology training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(3):353–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankaranarayanan G, Lin H, Arikatla VS, Mulcare M, Zhang L, Derevianko A, et al. Preliminary face and construct validatio study of a virtual basic laparoscopic skill trainer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2010;20(2):153–157. doi: 10.1089/lap.2009.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chellali A, Dumas C, Melleville-Pennel I. Haptic communication to support biopsy procedures learning in virtual environments. Presnece: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. 2012;21(4):470–489. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panait L, Akkary E, Bell R, Robters K, et al. The Role of Haptic Feedback in Laparoscopic Simulation Training. J Surg Res. 2009;156(2):312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strom P, Hedman L, Sarna L, Kjellin A, et al. Early exposure to haptic feedback enhances performance in surgical simulator training: a prospective randomized crossover study in surgical residents. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(9):1383–1388. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0545-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arikatla V, Sankaranarayanan G, Ahn WWW, Chellali A, De S, Cao C, et al. Face and construct validation of a virtual peg transfer simulator. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(5):1721–1729. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2664-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Sankaranarayanan G, Arikatla V, Ahn W, Grosdemouge C, et al. Characterization of the learning curve of the VBLaST-PT (Virtual Basic Laparoscopic Skill Trainer) Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3603–3615. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2932-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chellali A, Zhang L, Sankaranarayanan G, Arikatla VS, Ahn W, Derevianko A, et al. Validation of the VBLaST peg transfer task: a first step toward an alternate training standard. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(10):2856–2862. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3538-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser SA, Klassen DR, Feldman LS, Ghitulescu GA, Stanbridge D, Fried GM. Valuating laparoscopic skills: setting the pass/fail score for the MISTELS system. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(6):964–967. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aggarwal R, Tully A, Larsen CR, Miskry T, Farthing A, Darzi A. Virtual reality simulation training can improve technical skills during laparosocpic salpingectomy for ectopic pregnancy. BJOG. 2006 Dec;113(12):1382–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janse JA, Goedegebuure RS, Veerema S, Broekmans FJ, Schreuder HW. Hysteroscopic sterilization using a virtual reality simulator: assessment of learning curve. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Nov-Dec;20(6):775–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]