Abstract

Massachusetts and the Netherlands have implemented comprehensive health reforms, which have heightened the importance of performance measurement. The performance measures addressing access to health care and patient experience are similar in the two jurisdictions, but measures of processes and outcomes of care differ considerably. In both jurisdictions, the use of health outcomes to compare the quality of health care organizations is limited, and specific information about costs is lacking. New legislation in both jurisdictions led to the establishment of institutes to monitor the quality of care, similar mandates to make the performance of health care providers transparent, and to establish a shared responsibility of providers, consumers and insurers to improve the quality of health care.

In Massachusetts a statewide mandatory quality measure set was established to monitor the quality of care. The Netherlands is stimulating development of performance measures by providers based on a mandatory framework for developing such measures. Both jurisdictions are expanding the use of patient-reported outcomes to support patient care, quality improvement, and performance comparisons with the aim of explicitly linking performance to new payment incentives.

Keywords: Health Care Quality Assessment, Quality Indicators, Health Care Reform

1. Introduction

Massachusetts and the Netherlands each implemented system-wide health reforms in 2006 [1, 2]. With a population of 6.5 million, Massachusetts’ reforms in 2006 achieved near-universal insurance coverage through increased public insurance for low-income residents and increased private coverage for middle and higher-income residents [2]. In August 2012 a law was enacted to reduce the growth in health care costs while also improving health care quality. Under supervision of a Health Policy Commission and informed by a new Center for Health Information and Analysis, Massachusetts is poised to address these challenges with a variety of performance measures [3]. As Massachusetts implements the blueprint that guides the new national health care reform in the United States, many eyes are focused on its efforts to improve quality and contain costs.

The reforms in the Netherlands, with 16.7 million residents, moved from a predominantly public insurance system with universal coverage towards a regulated privatized market system. In the beginning of 2012 the Minister of Healthcare announced the establishment of the Dutch Quality Institute to coordinate the monitoring of quality, accessibility and affordability of health care in the Netherlands.

A key component of the reforms in both jurisdictions was the establishment of regulated competitive insurance markets, which include a marketplace (called an “exchange” in the United States) where individuals and employers can compare and purchase health insurance plans. In addition, the reforms aim to establish regulated competitive markets for health care purchasing and health care provision. Regulated competition assumes that if these markets work properly, they will improve the quality of care and contain costs through increased efficiency [4].

The reforms increase the importance of performance measurement and reporting to support consumers in making informed decisions and to provide leverage for insurers as competitive purchasers. It provides care suppliers with benchmark information, helping them to increase their market share. The goals of performance measurement in this context are twofold: to promote accountability to the public and to improve the performance of the health system [5]. In this article we compare performance measurement in the health care systems of Massachusetts and the Netherlands. Our aim is to use this comparison to derive lessons about the challenges of using performance measurement to improve quality and to discuss avenues for addressing these challenges. We are not aiming at a comprehensive and detailed comparison but will explore three main avenues. First we describe the governance in both jurisdictions for monitoring the performance of the health care system. Second, we compare the availability of performance measures in Massachusetts and the Netherlands: what measures are available, by whom they are developed, collected and presented, and for what purposes. We limit our comparisons to publicly available, and therefore accessible, performance measures in both jurisdictions. Third, we compare the actual use of quality measures in Massachusetts and the Netherlands for choosing providers and health plans, and for performance-based contracting.

2. Comparative framework

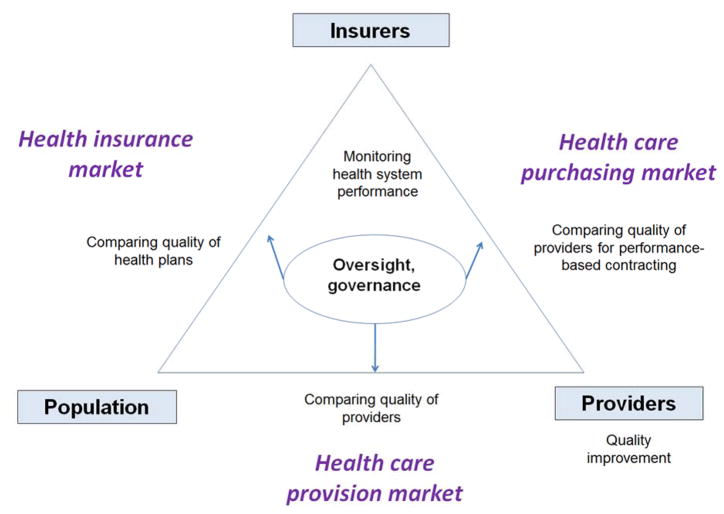

Performance measurement and reporting can occur at different levels and have different purposes, with consequences for the choice of measures and how they are collected and presented [6]. Health system performance can be used at several levels reflecting differing interactions between participants in the health care system. Clinicians may use quality measures to assess individual interactions with patients and for quality improvement within their organizations. Comparisons of the performance of health care providers can inform health insurers as they implement performance-based contracting, and public reporting can support patients and consumers in choosing health plans and providers. Taken together, performance measures enable government to monitor the quality of the health care system as a whole. Figure 1 summarizes the different purposes of quality measurement within the health care system and shows the involvement of multiple participants. In comparing the two jurisdictions we assessed the roles of these participants in collecting and using quality and performance information. We then analyzed similarities and differences in the approaches of Massachusetts and the Netherlands.

Figure 1.

Comparative framework for the use of quality measures

The comparisons were informed by a targeted literature search in PubMED and Google Scholar to find both peer reviewed publications and grey literature. We used a wide-angle approach using combinations of the following search terms: performance measures, quality indicators, accreditation, certification, pay for performance, payment, incentive, quality, consumer decision making, patient decision making, consumer choice, patient choice, Massachusetts, and the Netherlands. In addition, we used policy documents, websites and information from key-informants in both jurisdictions.

3. Governance of Health Care System Performance

Performance information is essential for the regulatory role of government to monitor the overall quality of the system. Specifically, monitoring can assure a level playing field to guide the market rules for competition [7]. The governments in Massachusetts and the Netherlands established institutions to stimulate coherent and comprehensive monitoring of safety, quality, and effectiveness of healthcare, and to allow for linking these aspects to monitoring of the costs of care.

Based on the recently adopted legislation in Massachusetts a new Health Policy Commission was established to monitor the reform of the health care delivery and payment systems in Massachusetts and to develop policy to reduce overall cost growth while improving the quality of patient care. The newly established Center for Health Information and Analysis will report on health care quality and cost on behalf of the Commission. The legislation includes the mandate for a Statewide Quality Advisory Committee (SQAC) to recommend a standard quality measure set for public reporting. The Committee delivered its first set of recommendations by the end of 2012 and the standardized set of 135 quality indicators is expected to be implemented under the new legislation, through expanded public reporting of quality and costs of health care providers for the most common health care services [8].

In the Netherlands, the newly established governmental Dutch Quality Institute started operating in 2012 and will reside under the Dutch Healthcare Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland) for monitoring the quality of care. The main task of the Institute is to impose a mandatory framework for the development of care standards, clinical guidelines and performance measures. The mandate of the Institute will be law enforced. Its role is to facilitate the development of multiple sets of disease- and provider-specific quality measures. The Institute will develop quality measures if providers do not take responsibility themselves. The Institute is not responsible for affordability and accessibility of health care which is instead included within another department of the Dutch Healthcare Institute.

4. Availability of Quality Measures

Quality measures are derived from data collected via patients, health care providers and health plans. Patient-reported, clinical and administrative data are then used to quantify the quality of a selected aspect of care. Requirements for validity and reliability are high when using quality measures for accountability, and data are expected to be collected through standardized and detailed specifications [6]. In both jurisdictions quality measure sets have been developed to allow for the publication of comparative information.

Characteristics of publicly reported quality measures at the hospital or physician group level in Massachusetts and the Netherlands are presented in Table 1. Publicly reported quality measure sets in Massachusetts are dominated by four mandated sets [9]: (1) Hospital process measures as developed under auspices of the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), (2) the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Survey (HCAPHS) developed under auspices of the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ), (3) the Healthcare Effectiveness and Data and Information Set (HEDIS) as developed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), and (4) the Ambulatory Care Experiences Survey (ACES) as developed by Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (MHQP). MHQP is a non-profit coalition of physicians, hospitals, health plans, purchasers, patient and public representatives, academics, and government agencies working together to promote improvement in the quality of health care services in Massachusetts [10]. A statewide report by the governmental Division of Health Care Finance and Policy provides insight in the cost and quality of hospitals in Massachusetts using 38 cost measures and 33 quality measures [11].

Table 1.

Examples of publicly reported quality measures at hospital or medical group level in Massachusetts and the Netherlands

| Indicators | Massachusetts | Massachusetts and the Netherlands | Netherlands |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening and prevention | Well-child visits Colorectal cancer screening Chlamydia screening |

Breast cancer screening* Cervical cancer screening* |

|

| Process of Health Care | CVD management Imaging tests LBP when appropriate Spirometry test COPD Pediatric medication and testing AMI management Heart failure management Pneumonia management |

Diabetes management Medication monitoring (Surgical) infection prevention |

Pain management in surgery and childbirth Volume of surgical procedures Breast cancer management Stroke management Hip fracture surgery <24 hours hospitalization Hip replacement management Ear/nose/throat surgery management Urinary incontinence management |

| Health Outcomes | Risk-adjusted Readmission Rates for heart attack, heart failure, pneumonia | Massachusetts: Mortality (HSMR) for angioplasty, bypass surgery, hip fracture, hip replacement, stroke, heart attack, heart failure, pneumonia Netherlands: Overall HSMR; death after hospitalization heart attack & angioplasty |

Pain severity after surgery Residual malignant tissue after breast cancer surgery Re-surgery incidence (hip fracture, colorectal cancer, ear/nose/throat surgery) Death <1 yr after cardiology outpatient consult |

| Access to Health care | Access to preventive services, ambulatory services, primary care physician, annual dental visit, substance abuse therapy | ||

| Patient Experience | HCAHPS CG-CAHPS ACES |

Dutch CQ-index is based on CAHPS methodology and measures similar domains. ACES and CQ- Primary Care Physician index** cover similar domains. | CQ-index |

Source: Public websites; Massachusetts: hospital compare, my healthcare options, quality insights, Netherlands: kiesbeter.nl, ziekenhuizentransparant.nl Notes CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; LBP: Low Back Pain; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; HSMR: Hospital Standardized Mortality Rate; HCAPHS: Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers; CG-CAHPS: Clinician/Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers; CQ-index: Consumer Quality Index;

Conducted by regional groups within national population screening programs;

Results of CQ-Primary Care Physician Index are not publicly available yet.

In the Netherlands, quality measure sets for different providers (e.g. hospitals, pharmacy, mental healthcare, physical therapy practices) and specific diseases (diabetes, COPD, cardiovascular risk management) have been developed under the auspices of the Health Care Inspectorate [12, 13]. Patient experience is captured via the Consumer Quality Index (CQ-index). The use of the CQ-index by insurers is coordinated by the Miletus foundation, a collaborative of health insurers in the Netherlands; another large part of the development and use of the CQ-index runs via patient organizations. The quasi-governmental National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) has been commissioned by the Minister of Health Care to assess the performance of the Dutch health care system. RIVM uses a set of 125 indicators for monitoring aspects of healthcare at aggregate level [14].

Detailed description and comparisons of available quality measure sets in both jurisdictions are presented in the Supplementary file. The majority of quality measures in both settings are aimed at the process of care, although the specifications show substantial differences between the measures. The availability of health outcome measures is limited in both settings. Blood pressure, Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1C) and Cholesterol levels (LDL) are commonly used clinical outcome measures in Massachusetts [10]. In the Netherlands a widely used clinical outcome measure is pain level after surgery.

Patient experience in the Netherlands is assessed with the Dutch CQ-index and in and Massachusetts using the American CAHPS survey. These surveys are based on similar methodology [15]. Massachusetts Health Quality Partners uses a survey instrument for patient experience in primary care derived from the clinician/group CAPHS survey and the state mandated ACES survey [10]. The Dutch CQ-index includes several instruments that measure patient experiences with a broad spectrum of specific conditions or specific hospital procedures, including patient-reported outcome measures that are aimed at capturing (physical) functioning and the outcome appropriate for the intervention measured [16].

4.1 Quality improvement

Quality improvement is inherent to the professional responsibility of health care providers and the formative use of indicators for quality improvement is considered to be of great benefit to be discussed and interpreted by clinicians in the light of local contexts [17, 18]. Data may be used for self-reflection and continuous education of individual health care providers, or for benchmarking and strategic purposes of the healthcare organization. A variety of sources for quality measures may be used, and data collection and interpretation is usually conducted at the practice level. For use in Massachusetts and other US states, clinical quality measures for specific diseases and evidence-based treatment interventions are published in the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (NQMC) by the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ). Measure developers are usually professional bodies who are encouraged by AHRQ to submit their quality measures for consideration. Each submitted measure is reviewed against a standard set of inclusion criteria for the NQMC [19]. In the Netherlands, clinical quality measures have been developed and endorsed by professional bodies, which typically derive from recommendations in clinical practice guidelines [20].

4.2 Comparing the quality of providers

Consumer comparisons of the quality of health care providers are supported by publicly-available performance data disseminated by governments in both jurisdictions; even if the data are collected by private sector organizations. In Massachusetts, the interactive website My HealthCare Options, sponsored by the governmental Health Care Quality and Cost Council, supports patients and families in selecting a hospital or primary care group [21]. The Council publishes ratings from other recognized organizations such as Massachusetts Healthcare Quality Partners (MHQP) and calculates some new ratings from their own health care database. Quality and cost ratings can be searched by location, provider, medical condition or procedure. The ratings for specific providers are reported as below, equivalent to, or above the state average. Cost ratings are limited due to lack of available data from providers. Data on the quality of primary care groups can also be searched by location, medical group, doctor’s office, and doctor’s name via the interactive website of MHQP [10].

Quality ratings of hospitals, nursing homes, home care organizations, and disabilities care organizations in the Netherlands are published on the government-funded website Kiesbeter.nl [choosing better] [22]. The presented data are based on a variety of resources and ratings have three levels, corresponding to quality that is below, equivalent to, or above the national average. The website also shows the accreditation status of providers and provides limited information on costs. Sixty-one hospitals are currently accredited, which is approximately 50% of all hospitals in the Netherlands [23].

4.3 Comparing the quality of health plans

Massachusetts’ residents can use the accreditation status of health plans as conducted by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) to make an informed choice about purchasing coverage with a specific health plan. Accreditation is voluntary but all 13 Health Maintenance Organizations and Medicaid health plans in Massachusetts (n=13) were NCQA accredited in 2011, compared to approximately 60% of health plans in the rest of the US. The Massachusetts Health Connector acts as an insurance exchange where private health plans are offered and people are given information for choosing a health plan [24]. At the state level an annual report about the quality of care and service of health plans is published by the governmental Division of Health Care Finance and Policy based on HEDIS data [25].

In the Netherlands, the governmental website Kiesbeter.nl provides an interface to compare premiums, deductibles and supplementary coverage for all health plans. Similar information is provided on private websites such as Independer.nl and Consumentenbond.nl. A quality rating of the administrative services of health plans is also included on Kiesbeter.nl based on experience of consumers. Health plans received confidential reports in which their performance is compared with the average across all health plans based on consumer experience [26]. However, due to budget cuts and private initiatives these ratings are no longer collected and published on the governmental website.

A key difference between the Massachusetts Health Connector and the Dutch consumer websites is that the Health Connector was established to support low- and middle-income residents to obtain subsidized health insurance, and to create a health insurance exchange to assist higher-income residents to obtain unsubsidized insurance. Health plans of the Health Connector are offered by a selected number of insurers and carry the seal of approval of the Health Connector for high quality and good value. The Dutch websites are aimed at comparisons of all available insurers.

5. The use of quality measures in practice

5.1 Quality improvement

Many health care organizations and providers use quality indicators for quality improvement activities, although this type of use rarely results in publicly available information [27]. Structural capabilities intended to improve quality of care among physician groups in Massachusetts, such as frequent meetings to discuss quality and physician awareness of patient experience ratings, were associated with better performance [28, 29]. The majority of Massachusetts physician groups that receive patient experience reports are engaged in efforts to improve patient experience [30]. Examples of the use of indicators for quality improvement in the Netherlands have been published for head-neck cancer, diabetes and pneumonia [31].

5.2 Choosing providers

The evidence for the consumers’ or patients’ use of quality information to select providers in Massachusetts and the Netherlands is limited. A Massachusetts survey in 2007 showed that the lack of objective information or independent ratings of doctors and hospitals led consumers to rely primarily on subjective recommendations from professionals, friends and family [32]. An evaluation of the website kiesbeter.nl in the Netherlands showed that most visitors reported it was not useful in their decision making [33]. In addition, a survey of Dutch households showed that respondents tend to stay with their general practitioner even if they had the option to switch to a higher quality alternative [34].

5.3 Choosing health plans

Consumer mobility between health plans is considered important for adequate functioning of the health care markets. However, in both jurisdictions the ability of people to switch between health plans is limited due to the large proportion of collective contracting via employers or other group purchasing organizations. Many consumers rely on a group purchasing organization to assess information about quality, patient experience and price [35]. After initial implementation of health reform in the Netherlands about 18% of people switched to a different insurance company, while mobility decreased to 3% in 2009. Recent estimates show an increasing switching rate (6–8%), mainly due to increased premiums [36]. Surveys in the Netherlands have shown that costs and to a lesser extent the benefits package are the main drivers for switching insurance plans, as opposed to quality [37].

5.4 Performance-based contracting

Health insurers are increasingly using quality information for performance-based payment and selective contracting of providers [38]. One model, pay-for-performance gives providers financial incentives to increase quality of care. Massachusetts has ample experience with pay-for-performance. As early as 2004, 89% of Massachusetts physician groups had pay-for-performance incentives [39]. However, early evaluations of pay-for-performance initiatives show limited impact on improving quality [40–42]. A promising approach was introduced in 2009 with the Alternative Quality Contract (AQC) by the largest insurer in the state. AQC is a hybrid payment reform model based on global payment and pay-for-performance. Providers receive an annual fee for the care of each patient, with higher payments for patients deemed to be greater health risks and with bonuses for high-quality care. Early results suggest that global budgets with pay-for-performance slow the growth in medical spending while improving quality of care. An important success factor of the AQC project is the partnership between the insurer and health care providers [43].

In the Netherlands, experience with pay for performance is limited, although a recent study concluded that the Netherlands seems well suited for pay for performance, based on existing risk adjustment data collected by health plans and the introduction of bundled payments for chronic disease care [44]. Early results from adoption of bundled payment for diabetes care in the Netherlands show improvement in care coordination, although it is too early to draw conclusions about the effects of the new payment system on the quality or the overall costs of care [45].

6. Implications for future policy

The recent developments in Massachusetts and the Netherlands to stimulate performance measurement share many similarities, but also some important differences. We highlight lessons in four key areas of future policy: (1) governance of performance measurement, (2) availability of quality measures, (3) the use of quality measures, and (4) integration of data collection

6.1 Governance of performance measurement

Both jurisdictions are in still in early stages of implementing legislation with newly established institutions and the next several years will be a test of their objectives. The objectives of the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission are comprehensive, looking at multiple aspects of reforming health care delivery and payment systems in Massachusetts. The Dutch Quality Institute’s objectives are more narrowly defined with a focus on the quality of health. In monitoring the quality of the health care system, the Dutch Quality Institute and the Massachusetts Health Policy Committee have a similar mandate. They can require providers to provide data about their quality, but do not have direct regulatory power to force the system to change. Instead they will monitor the quality of health care and are aiming at establishing a shared responsibility of providers, consumers and insurers to improve the quality of health care. Both institutions rely heavily on the partnership with health care providers in establishing monitoring systems. Health care providers collect and produce the data while the state and national institutions establish the rules and standards that promote comparability and validity of the data.

6.2 Availability of quality measures

Our description showed the limited use of measures that capture patient-reported and other clinical health outcomes in the two jurisdictions. Among the reasons that health outcome measures are less well developed is that they are less feasible, more subject to confounding, and less directly actionable than process measures. Outcome measures often require risk adjustment for specific populations in assessing benefits or changes related to specific health interventions [6]. Both jurisdictions aim to expand the use of outcome measures and are starting to address the challenges of data collection and analysis.

The abundance of available measures in both jurisdictions creates the risk of overload of quality information. Massachusetts addressed this issue by prioritizing measures based on sufficient validity and practicality. However, its first standard set still contains 135 quality measures out of 186 measures considered for inclusion. The Dutch Quality institute does not aim at establishing a list of mandated quality measures. Instead, stakeholders in healthcare will be able to submit quality measures to a public registry if the measures meet certain (methodological) criteria. The Dutch Quality Institute published a framework with criteria for the development of standards of care, clinical practice guidelines and quality measures in anticipation of its formal endorsement role [46].

The different approaches of the two jurisdictions in establishing quality measures may have consequences for their further use. The Massachusetts’ approach (a mandated standard quality measure set) increases comparability between providers, and may facilitate informed decision making of consumers and purchasers of health care. The Dutch approach (a registry of endorsed measures that providers can select) may lead to variable selection of quality measures, thus limiting comparability. The Netherlands could learn from the approach in Massachusetts by establishing a minimum set of quality measures for longitudinal monitoring, which would also allow for international comparisons when common measures are used. For both jurisdictions we recommend selecting a small core set of quality measures to increase the feasibility for longitudinal monitoring and comparisons.

A strength of the Dutch approach is that quality measures developed by clinical groups typically result in measures useful internally for quality improvement and providers may be more inclined to use them. Engagement of providers in data collection and use of quality measures is essential for a sustainable system of performance measurement and is a key component for further implementation. Massachusetts may learn from the Dutch approach to stimulate providers to take responsibility themselves, thus increasing the likelihood that they are actually utilized.

6.3 The use of quality measures in practice

The limited use of quality information by consumers in selecting providers is striking given that consumers report valuing quality information about their providers; yet a vast majority of the public says that they have never seen comparative quality information [47]. Evidence that public reporting stimulates quality improvement of providers is stronger, suggesting that quality improvement activities increase in response to public report cards [48, 49]. Limited evidence exists for choosing health plans, suggesting that consumers tend to choose health plans that perform better, although use of the data in health plan choice varies among consumers and across population subgroups [48, 50–52].

Both jurisdictions aim to support consumer decisions. This includes an important task to present the quality and cost of health care services in a format that is understandable and valuable to consumers and which actually improves the likelihood that they will use the data to make informed decisions. Evidence suggests that presenting cost data alongside easy to interpret quality information and highlighting high-value options improves the likelihood that consumers will choose those options [53]. Many consumers continue to believe that more care is better care and that higher cost is a signal of higher quality [54]. The challenge is in presenting and targeting the available information to support decision making [55]. Analysis of preference profiles of consumers shows that comparative information derived from quality measures indeed can support consumers in fulfilling as critical role in choosing providers. However this will only be effective if the information is tailored to the specific situation of the patient [56].

New models of performance-based contracting are emerging in Massachusetts based on partnership between insurers and health care providers. Further development of such payment reform models may assist in the stimulating the meaningful use of quality measures for a variety of purposes. Initiatives in the Netherlands can build on the Massachusetts experience.

6.4 Integration of data collection

Data collection for quality improvement purposes is provided by health care professionals and patients, and it is a challenge to aggregate information at a higher level for accountability purposes in such a way that transparency is experienced by healthcare providers as positive and not as burden. Overcoming this challenge should be the main focus in both Massachusetts and the Netherlands, by creating quality measure sets that can be used both at the level of quality improvement and at the aggregate level. A promising initiative to address this challenge is the use of patient-reported outcome measures. These measures have the potential to be used at the aggregate level for performance measurement while simultaneously serving their purpose at the clinical level to focus on a patient’s individual health goals across a variety of dimensions [57].

An initiative for implementing patient-reported outcome measures at both the clinical and aggregate levels has been launched by Partners HealthCare, the largest provider organization in Massachusetts. In addition, Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (MHQP) aims at advancing the adoption of patient-reported outcomes measurement and reporting across Massachusetts as key strategic priority for 2013. Also in the Netherlands several initiatives have been established. Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center started a project to use outcomes as reported by patients for reducing variation in clinical practice [58]. The Miletus Foundation initiated a platform for researchers to stimulate national collaboration in the development, use and evaluation of patient-reported outcomes.

7. Conclusion

The Massachusetts Health Policy Commission and the Dutch Quality Institute share a similar mandate to monitor the quality of the health care system. Both jurisdictions rely on and should further invest in engagement of and partnership with patients, health care providers and insurers in order to establish reliable and meaningful quality monitoring systems. The main challenges are (a) to create a routine flow of data collection that allows for use at the clinical level and quality improvement, as well as for aggregation of the data at a higher level for accountability purposes and performance-based contracting; (b) to establish a carefully-selected core set of standardized quality measures which includes patient-reported health outcomes in order to prevent an overload of quality information, and (c) to present easy to interpret and tailored information on quality and cost to support decision making of consumers. The tasks are formidable. The two jurisdictions should be able to learn from each other, especially when they select different solutions to the same challenge. More generally, increased monitoring and exchange of experiences regarding the use of performance indicators across many jurisdictions would be helpful in meeting one the largest challenges facing health systems today.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr. Van der Wees and Dr. Van Ginneken are supported by a Harkness Fellowship in Health Policy and Practice from the Commonwealth Fund. The views presented here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to The Commonwealth Fund or its directors, officers, or staff. Dr. Ayanian is supported by the Health Disparities Research Program of Harvard Catalyst/The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH Award #UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers). The sponsors did not have a role in the study design, data collection and analysis, or writing of the report.

Contributor Information

Philip J. Van der Wees, Email: p.vanderwees@iq.umcn.nl, vanderwees@hcp.med.harvard.edu.

Maria W.G. Nijhuis-van der Sanden, Email: r.nijhuis@iq.umcn.nl.

Ewout van Ginneken, Email: ewout.vanginneken@tu-berlin.de, evangin@hsph.harvard.edu.

John Z. Ayanian, Email: ayanian@hcp.med.harvard.edu.

Eric C. Schneider, Email: eschneid@rand.org.

Gert P. Westert, Email: g.westert@iq.umcn.nl.

References

- 1.van de Ven WP, Schut FT. Universal mandatory health insurance in the Netherlands: a model for the United States? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):771–781. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonough JE, Rosman B, Butt M, Tucker L, Howe LK. Massachusetts health reform implementation: major progress and future challenges. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(4):w285–297. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.w285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayanian JZ, Van der Wees PJ. Tackling rising health care costs in Massachusetts. New Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):790–793. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1208710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enthoven AC. The history and principles of managed competition. Health Aff (Millwood) 1993;12(Suppl):24–48. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.suppl_1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PC, Mossialos E, Papanicolas, Leatherman S. European Osservatory on Health Systems and Policies. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2009. Performance Measurement for Health System Improvement: experiences, challenges and prospects. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner LA, Snow V, Weiss KB, Amundson G, Schneider E, Casey D, Hornbake ER, Manaker S, Pawlson LG, Reynolds P, et al. Leveraging improvement in quality and value in health care through a clinical performance measure framework: a recommendation of the American College of Physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25(5):336–342. doi: 10.1177/1062860610366589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Ginneken E, Swartz K. Implementing insurance exchanges--lessons from Europe. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(8):691–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1205832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SQAC: Statewide Quality Advisory Committee. Year 1 Final Report. Boston: Center for Health Information and Analysis; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.An Act to promote cost containment, transparency and efficiency in the provision of quality health insurance for individuals and small businesses. Chapter 288 of 2010; 2010

- 10.Massachusetts Healthcare Quality Partners (MHQP) Quality Insights: Healthcare Performance in Massachusetts. 2013 Available from: http://www.mhqp.org/quality/whatisquality.asp?nav=030000.

- 11.DHCFP: Measuring Health care Quality and Cost in Massachusetts. Boston: Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zichtbare Zorg. 2012 Available from: http://www.zichtbarezorg.nl/page/Programma-Zichtbare-Zorg.

- 13.Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg. Kwaliteitsindicatoren. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westert G, van den Berg MJ, Zwakhals SLN, Heijink R, de Jong JD, Verkleij H. Dutch Health Care Performance Report. Bilthoven: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delnoij DMJ, ten Asbroek G, Arah OA, de koning JS, Stam P, Vries P, Klazinga NS. Made in the USA: the import of American Consumer Assessment of Health Plan Surveys (CAHPS®) into the Dutch social insurance system. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(6):652–659. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Boer D, Delnoij D, Rademakers J. The discriminative power of patient experience surveys. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:332. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landon BE. Use of quality indicators in patient care: a senior primary care physician trying to take good care of his patients. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(9):956–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman T. Using performance indicators to improve health care quality in the public sector: a review of the literature. Health services management research: an official journal of the Association of University Programs in Health Administration/HSMC, AUPHA. 2002;15(2):126–37. doi: 10.1258/0951484021912897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) 2012 doi: 10.1080/15360280802537332. Available from: http://qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.CBO. Handleiding Indicatorontwikkeling. Utrecht: CBO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.My health Care Options. Massachusetts Health Care Quallity and Cost Council; 2013. Available from: http://hcqcc.hcf.state.ma.us. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiesbeter.nl. 2013 Available from: http://www.kiesbeter.nl/zorg-en-kwaliteit/zoek-op-kwaliteit/

- 23.Accrediation of hospitals. NIAZ; 2012. Available from: www.niaz.nl. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority. 2012 Available from: https://www.mahealthconnector.org/portal/site/connector/template.PAGE/menuitem.55b6e23ac6627f40dbef6f47d7468a0c.

- 25.DHCFP. Guide to managed care in Massachusetts. Boston: Division of Health Care Finance and Policy; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendriks M, Spreeuwenberg P, Rademakers J, Delnoij DM. Dutch healthcare reform: did it result in performance improvement of health plans? A comparison of consumer experiences over time. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:167. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussey PS, Mattke S, Morse L, Ridgely MS. health R, editor. Evaluation of the use of AHRQ and other quality indicators. Santa Monica: RAND; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedberg MW, Safran DG, Coltin KL, Dresser M, Schneider EC. Readiness for the Patient-Centered Medical Home: structural capabilities of Massachusetts primary care practices. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24(2):162–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0856-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedberg MW, Coltin KL, Safran DG, Dresser M, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC. Associations between structural capabilities of primary care practices and performance on selected quality measures. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151(7):456–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-7-200910060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedberg MW, SteelFisher GK, Karp M, Schneider EC. Physician groups’ use of data from patient experience surveys. Journal of general internal medicine. 2011;26(5):498–504. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1597-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wollersheim H, Hermens R, Hulscher M, Braspenning J, Ouwens M, Schouten J, et al. Clinical indicators: development and applications. The Netherlands journal of medicine. 2007;65(1):15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.BCBS. Looking for answers: How consumers make health care decisions in Massachusetts. Boston: Blue Cross Blue Shield Massachusetts; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colijn JJ. Gebruik en waardering van kiesBeter.nl in 2009. Bilthoven: RIVM; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boonen LH, Donkers B, Schut FT. Channeling consumers to preferred providers and the impact of status quo bias: does type of provider matter? Health Serv Res. 2011;46(2):510–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lako CJ, Rosenau P, Daw C. Switching health insurance plans: results from a health survey. Health Care Anal. 2011;19(4):312–328. doi: 10.1007/s10728-010-0154-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brabers AEM, Reitsma-van Rooijen M, De Jong JD. The Dutch health insurance system: Mostly competition on price rather than quality of care. Eurohealth. 2012;18(1):30–33. [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Jong JD, van den Brink-Muinen A, Groenewegen PP. The Dutch health insurance reform: switching between insurers, a comparison between the general population and the chronically ill and disabled. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider EC, Hussey PS, Schnyer C. Payment Reform: Analysis of models and performance measurement implications. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehrotra A, Pearson SD, Coltin KL, Kleinman KP, Singer JA, Rabson B, Schneider EC. The response of physician groups to P4P incentives. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(5):249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson SD, Schneider EC, Kleinman KP, Coltin KL, Singer JA. The impact of pay-for-performance on health care quality in Massachusetts, 2001–2003. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(4):1167–1176. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan AM, Blustein J. The effect of the MassHealth hospital pay-for-performance program on quality. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(3):712–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blustein J, Weissman JS, Ryan AM, Doran T, Hasnain-Wynia R. Analysis raises questions on whether pay-for-performance in Medicaid can efficiently reduce racial and ethnic disparities. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(6):1165–1175. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song Z, Safran DG, Landon BE, Landrum MB, He Y, Mechanic RE, Day MP, Chernew ME. The ‘Alternative Quality Contract,’ Based On A Global Budget, Lowered Medical Spending And Improved Quality. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(8):1885–1894. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pomp M. Background paper for the Council for Public Health and Health Care. Raad voor de Volksgezondheid en Zorg; 2010. Pay for performance and health outcomes: a next step in Dutch health care reform? [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Bakker DH, Struijs JN, Baan CB, Raams J, de Wildt JE, Vrijhoef HJ, Schut FT. Early results from adoption of bundled payment for diabetes care in the Netherlands show improvement in care coordination. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(2):426–433. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.College voor Zorgverzekeringen (CVZ) Toetsingskader kwaliteitsstandaarden en meetinstrumenten [Proposal for an assessment framework for care standards and quality measures in health care] Diemen: CVZ; 2013. Consultatiedocument. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sinaiko AD, Eastman D, Rosenthal MB. How report cards on physicians, physician groups, and hospitals can have greater impact on consumer choices. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012 Mar;31(3):602–611. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jan 15;148(2):111–123. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith MA, Wright A, Queram C, Lamb GC. Public reporting helped drive quality improvement in outpatient diabetes care among wisconsin physician groups. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012 Mar;31(3):570–577. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faber M, Bosch M, Wollersheim H, Leatherman S, Grol R. Public reporting in health care: how do consumers use quality-of-care information? A systematic review. Medical care. 2009 Jan;47(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181808bb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolstad JT, Chernew ME. Quality and consumer decision making in the market for health insurance and health care services. Med Care Res Rev. 2009 Feb;66(1 Suppl):28S–52S. doi: 10.1177/1077558708325887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ketelaar NA, Faber MJ, Flottorp S, Rygh LH, Deane KH, Eccles MP. Public release of performance data in changing the behaviour of healthcare consumers, professionals or organisations. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011;11:CD004538. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004538.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hibbard JH, Greene J, Sofaer S, Firminger K, Hirsh J. An experiment shows that a well-designed report on costs and quality can help consumers choose high-value health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(3):560–568. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehrotra A, Hussey PS, Milstein A, Hibbard JH. Consumers’ And Providers’ Responses To Public Cost Reports, And How To Raise The Likelihood Of Achieving Desired Results. Health Aff (Milwood) 2012;31(4):843–51. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hibbard JH, Peters E. Supporting informed consumer health care decisions: data presentation approaches that facilitate the use of information in choice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24:413–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.141005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Groenewoud S. A study of search and selection processes and the use of performance indicators in different patient groups. Rotterdam: Erasmus University; 2008. It’s your choice. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. Goal-oriented patient care--an alternative health outcomes paradigm. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):777–779. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1113631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lamberts MP, Drenth JP, van Laarhoven CJ, Westert GP. Outcome of treatment reported by patients: instrument to reduce variations in clinical practice. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2013;157(7):A5369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.