Summary

Sheep breeds show a broad spectrum of different horn phenotypes. In most modern production breeds, sheep are polled (absence of horns), whereas horns occur mainly in indigenous breeds. Previous studies mapped the responsible locus to the region of the RXFP2 gene on ovine chromosome 10. A 4‐kb region of the 3′‐end of RXFP2 was amplified in horned and polled animals from seven Swiss sheep breeds. Sequence analysis identified a 1833‐bp genomic insertion located in the 3′‐UTR region of RXFP2 present in polled animals only. An efficient PCR‐based genotyping method to determine the polled genotype of individual sheep is presented. Comparative sequence analyses revealed evidence that the polled‐associated insertion adds a potential antisense RNA sequence of EEF1A1 to the 3′‐end of RXFP2 transcripts.

Keywords: antisense RNA, horn growth, polledness, relaxin/insulin‐like family peptide receptor 2, sheep

Horns in ruminants not only serve the purpose of self‐defense against predators but also play an important role in sexual selection through intramale competition. Therefore, horns are an interesting trait not only from an animal breeding but also from an evolutionary perspective (Johnston et al. 2013; Robinson et al. 2006). Nowadays, in domestic sheep there are many breeds which are fixed for polledness as well as some extensively used indigenous breeds that are fully horned.

The development of horns in sheep is controlled by an autosomal locus (OMIA 000483‐9940). Initially an inheritance model with three alleles was proposed: H+ for horns, HL for sex‐limited horns and HP for polledness (Dolling 1961; Coltman & Pemberton 2004). The horn allele has been mapped to OAR 10 in Merino × Romney crosses (Montgomery et al. 1996) as well as in Soay sheep (Beraldi et al. 2006; Johnston et al. 2010). A genome‐wide association study in Soay sheep showed a high association between a SNP on OAR 10 at position 29 415 140 (sheep genome assembly version 3.1) and the horn phenotype (Johnston et al. 2011). Subsequent fine‐mapping revealed the most significant association in the flanking region of the 3′‐end of the relaxin/insulin‐like family peptide receptor 2 (RXFP2) gene. The best associated SNP was located at position 29 455 959 and was shown to be highly predictive for the expression of horns in Soay sheep (Johnston et al. 2011). Independently, a SNP at OAR 10 position 29 389 966 was found to be highly predictive for the polled phenotype in an experimental population of Merino sheep, whereas a dominant maternal imprinting effect of the polled allele was suggested (Dominik et al. 2012).

The associated region in the sheep genome is located on a completely different segment of the genome as the known mutations involved in horn growth of goats and cattle. In goats, the absence of horns is caused by an 11.7‐kb deletion on CHI 1q43 which encompasses no coding regions but exerts regulatory effects on transcripts located nearby (Pailhoux et al. 2001). In polled cattle, two common independent mutations at 1.7 and 1.9 Mb on BTA 1 affecting non‐coding regions that lead to complex gene expression differences have been identified (Medugorac et al. 2012; Allais‐Bonnet et al. 2013; Rothammer et al. 2014; Wiedemar et al. 2014). Additionally, two sporadic de novo mutations affecting horn growth in the absence of the known polled mutations have been described (Capitan et al. 2011, 2012).

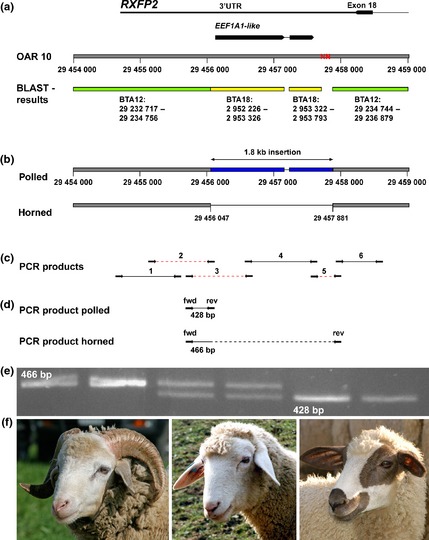

To identify the detailed molecular nature of the ovine mutation causing polledness, the region previously shown to be associated with horn growth in sheep was investigated by sequencing the last exon and the 3′‐UTR (untranslated region) of RXFP2. Primers for six PCR products spanning a 4‐kb segment (Fig. 1c, Table S1) were designed based on the sheep reference genome of a polled Texel sheep. PCR products spanned the last coding exon of RXFP2 and 3500 bp downstream (OAR 10: 29 454 625–29 458 615; Fig. 1c) including a gap in the reference sequence (OAR 10:29 457 699–29 457 798). PCR was performed using animals of polled and horned Swiss sheep breeds (Table 1). PCRs were carried out in 10‐μl volumes with 5 pmol of each primer, 5 μl of Amlitaq Gold 360 Master Mix (LifeTechnologies), 1 μl of 360 GC Enhancer (LifeTechnologies) and 20 ng of genomic DNA. The amplification conditions were 10 min at 95 °C, 32 cycles of 30 s of denaturation at 95 °C, 30 s of annealing at 60 °C and 1 min of elongation at 72 °C, followed by a 7‐min hold at 72 °C. Subsequently, PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel and visualized after staining with ethidium bromide. All PCR products were successfully amplified in polled animals and showed the expected sizes, whereas the product spanning the gap in the reference sequence was 30 bp larger than expected. In contrast, three of the six PCR products were not obtained in the samples of the horned sheep (Fig. 1). Comparative sequence analysis of the sheep with the bovine reference sequence showed two significant blast matches of the segment of OAR 10 to a contiguous region on BTA 12 (Fig. 1a). In detail, the OAR 10 region from 29 454 000 to 29 456 047 corresponds to a region on BTA 12: 29 232 717–29 234 756 (cattle genome assembly UMD3.1) and the OAR 10: 29 457 880–29 459 000 segment corresponds to BTA12: 29 234 744–29 236 879 with 92% and 95% sequence identity respectively. Interestingly, the 1.65‐kb segment in between (OAR 10: 29 456 048–29 457 698) showed several sequence matches on the bovine genome, the most significant being located on BTA 18: 2 952 226–2 953 326 and 2 953 322–2 953 793; BTA 1: 77 037 254–77 036 156 and 77 036 160–77 035 689; BTA 23: 29 962 732–29 961 633 and 29 961 637–29 961 170; BTA 3: 11 905 282–11 904 182 and 11 904 186–11 903 715; and BTA 7: 34 616 886–34 615 793 and 34 615 797–34 615 326 showing sequence identity of 98% (Fig. 1a). As this genomic segment matches other places in the genome of horned cattle, a genomic insertion in the flanking 3′‐region of RXFP2 in hornless sheep was suspected. To check the presence/absence of this potentially inserted segment in horned and polled sheep, primers spanning the whole potential insertion were used to amplify PCR products in horned and polled sheep (Fig. 1d). Interestingly, these PCR products were successfully amplified in the horned sheep, but not in the polled animals.

Figure 1.

A 1.8‐kb insertion in the 3′‐UTR of ovine RXFP2. (a) The gray bar represents the ovine reference sequence of the 3′‐flanking region of RXFP2. The annotated genes are displayed on top of the bar. Note the gap in the reference sequence marked with the red ‘N’. The second bar represents the respective bovine regions obtained by blasting the sheep sequence with the bovine genome. The matches to bovine chromosome 12 are displayed in green and the matches to chromosome 18 in yellow. (b) The 3′‐flanking region of RXFP2 in polled and horned sheep. The 1833‐bp insertion is displayed in blue and marked with an arrow. It is present in polled and absent in horned sheep. (c) PCR products used for screening the region. Product numbers 2, 3 and 5 (marked with red dashed lines) do not amplify DNA of the horned sheep as they span the breakpoints of the insertion. (d) PCR products used for genotyping the insertion. One forward primer (fwd) is combined with two reverse primers (rev). The first reverse primer binds within the insertion and results in amplification of a PCR product of 428 bp. The other reverse primer binds after the insertion and the respective PCR product of 466 bp is amplified in the absence of the insertion. (e) Image of gel electrophoresis of the described PCR products used for genotyping of the insertion. The first two PCR products were obtained from two horned animals, which do not carry the insertion. The two following PCR products are from animals carrying the insertion in heterozygous state; these animals show a polled phenotype. The PCR products to the right were obtained from polled animals carrying the insertion in homozygous state. (f) Exemplary phenotypes matching with the gel image: A horned Bündner Oberländer sheep is shown on the left. A polled Bündner Oberländer sheep, which is heterozygous for the insertion, is shown in the center, and a polled Swiss Mirror sheep, which is homozygous for the insertion, is shown on the right.

Table 1.

Association of the 1.8‐kb insertion with horn phenotypes in Swiss sheep

| Breed | Phenotype | Genotype (1.8‐kb insertion) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt/wt | wt/ins | ins/ins | ||

| Bündner Oberländer sheep | Horned | 23 | ||

| Valais Red sheep | Horned | 48 | ||

| Valais Blacknose sheep | Horned | 48 | ||

| Bündner Oberländer sheep | Polled | 2 | ||

| Engadine Red sheep | Polled | 7 | ||

| Swiss Black‐Brown Mountain sheep | Polled | 19 | ||

| Swiss Mirror sheep | Polled | 47 | ||

| Swiss White Alpine sheep | Polled | 95 | ||

| Total | Horned | 119 | ||

| Polled | 2 | 168 | ||

Sequencing of the PCR products was performed using a BigDye Terminator v.3.1 cycle sequencing kit (LifeTechnologies) after purification with rAPid alkaline phosphatase (Roche) and exonuclease I (New England BioLabs). Sequencing products were resolved on an ABI 3730 capillary sequencer (LifeTechnologies), and the obtained sequence data were analyzed with sequencher 5.1 software. The obtained sequences confirmed the presence of the suggested insertion in polled sheep. Overall, the sequence of hornless sheep corresponds to the reference sequence, except for a segment of 83 bp (OAR 12: 29 457 116–29 457 198), which is present in the reference sequence but absent in the sequenced polled animals (Fig. 1b). In contrast, the sequence of horned sheep was identical to the sheep reference genome up to position OAR 10: 29 456 047, but the subsequent segment of 1833 bp (OAR 10: 29 456 048–29 457 880) was missing (Fig. 1b). This led to the conclusion that the DNA segment is inserted in polled sheep, but not in horned sheep.

A larger cohort of animals belonging to seven Swiss sheep breeds was subsequently genotyped for the presence or absence of this 1.8‐kb insertion (Table 1). Therefore, a forward primer upstream of the inserted segment (fwd 3) in combination with two different reverse primers was used (Fig. 1d), one within the inserted segment (rev 2) and another one distal of the inserted segment (rev 5). PCR was performed under the conditions described above with an elongation time of 45 s, and they were separated on a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. This primer combination led to the amplification of two different PCR products: a 428‐bp fragment if the insertion was present and a 466‐bp fragment in case of absence of the insertion (Fig. 1d,e). Genotyping of seven Engadine Red sheep, 19 Swiss Black‐Brown Mountain sheep, 47 Swiss Mirror sheep (polled), 48 Valais Blacknose sheep (horned), 95 Swiss White Alpine sheep (polled) and 48 Valais Red sheep (horned) revealed that all polled animals showed the insertion in a homozygous state and that it was absent in all horned animals. Genotyping of 25 Bündner Oberländer sheep, an indigenous breed in which animals with both phenotypes (horned and polled) occur, revealed the absence of the insertion in 23 horned animals and the heterozygous state of the insertion in two hornless animals. In conclusion, the genotyping in Swiss sheep showed an association of the 1.8‐kb insertion with the polled phenotype.

Within the polled‐associated insertion, two exons corresponding to the human eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1 (EEF1A1) gene are annotated as EEF1A1‐like in the sheep reference genome (Fig. 1a). The missing segment of 83 bp represents the intron of EEF1A1‐like (Fig. S1). This gene belongs to a family of conserved eukaryotic translation factors in humans which promote binding of aminoacyl‐tRNA to the ribosome (Lund et al. 1996). Human EEF1A1 consists of seven coding exons and has been found to have multiple copies on many chromosomes, some if not all of which represent different pseudogenes (Opdenakker et al. 1987; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/1915). Therefore, it can be assumed that the annotated ovine locus very likely represents a non‐active pseudogene. In addition, recently presented comparative mRNA‐sequencing data showed no expression differences of EEF1A1 (ENSBTAG00000034185) between horned and polled cattle fetuses, indicating no significant role of this transcript during bovine horn growth (Wiedemar et al. 2014). The inserted 1.8‐kb segment lies within the annotated 3.5 kb encompassing the 3′‐UTR of ovine RXFP2, a gene of the relaxin peptide receptor family. The encoded G protein‐coupled receptor is activated by insulin‐like 3 and, with a lower affinity, by relaxin 3 (Bathgate et al. 2013), which belongs to a gene family reported to be absent in ruminants (Wilkinson et al. 2005). RXFP2 is expressed mainly in reproductive tissues and is known to play a crucial role in testis descent; to a lesser extent, it is also expressed in blood, brain, kidney, muscle, thyroid, bone marrow and peripheral lymphocytes (Bathgate et al. 2013). In cattle, the expression of RXFP2 was significantly higher in developing horn buds of horned rather than polled fetuses (Allais‐Bonnet et al. 2013; Wiedemar et al. 2014). Conversely, expression of both ligands, INSL3 and RLN3, was absent in both horned and polled fetuses (Wiedemar et al. 2014).

As the ovine RXFP2 gene is transcribed from the strand opposite the EEF1A1‐like gene, the RXFP2 transcripts of sheep carrying the genomic insertion contain an antisense sequence of the EEF1A1‐like locus within their 3′‐UTR of the mRNA. Therefore, it could be speculated that EEF1A1 transcripts might bind to the 3′‐UTR of the RXFP2 mRNA and inhibit proper processing and translation of RXFP2 once the insertion is present. Sequence comparison of the 3′‐region of the ovine RXFP2 gene with the bovine sequence reveals that horned sheep lacking the 1.8‐kb insertion show a 3′‐UTR sequence more or less similar to that in the cow genome, whereas in polled sheep this sequence is interrupted by the identified 1.8‐kb insertion. It is known that 3′‐UTRs are crucial for mRNA stability and transportation as well as for the whole translation process (De Moor et al. 2005; Szostak & Gebauer 2013). Even if there is no antisense binding, the insertion in the 3′‐UTR present in polled sheep is likely to have an effect on the processing and translation of RXFP2 and might therefore inhibit normal horn growth. In contrast to reported associations of RXFP2 with human testis descent (Bathgate et al. 2013), homozygous polled rams do not show cryptorchidism. This is an indication that the consequence of the insertion is restricted to horn development.

In cattle, the development of horn‐like skin appendages (scurs) is seen only in animals carrying a polled mutation in the heterozygous state (Wiedemar et al. 2014). It would therefore be interesting to study the polled genotype of sheep showing scurs. In addition, the influence of sex on the development of horns (Johnston et al. 2011) or possible maternal imprinting effects (Dominik et al. 2012) should be taken into account and carefully studied in the future. This study provides an efficient PCR‐based method to determine the polled genotype of individual sheep, which is a prerequisite for a better understanding of the postulated inheritance models.

Supporting information

Table S1 Primers used for detection of the sheep polled mutation.

Figure S1 Sequences of horned and polled sheep.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all sheep breeders for providing blood samples of the animals. The authors would like to thank the Swiss sheep breeding association and ProSpecieRara for supporting the sampling. This study was funded in part by grant 31003A_141228 from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

References

- Allais‐Bonnet A., Grohs C., Medugorac I. et al (2013) Novel insights into the bovine polled phenotype and horn ontogenesis in Bovidae. PLoS One 8, e63512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate R.A., Halls M.L., van der Westhuizen E.T., Callander G.E., Kocan M. & Summers R.J. (2013) Relaxin family peptides and their receptors. Physiological Reviews 93, 405–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beraldi D., McRae A.F., Gratten J., Slate J., Visscher P.M. & Pemberton J.M. (2006) Development of a linkage map and mapping of phenotypic polymorphisms in a free‐living population of Soay sheep (Ovis aries). Genetics 173, 1521–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitan A., Grohs C., Weiss B., Rossignol M.N., Reversé P. & Eggen A. (2011) A newly described bovine type 2 scurs syndrome segregates with a frame‐shift mutation in TWIST1 . PLoS One 6, e22242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitan A., Allais‐Bonnet A., Pinton A. et al (2012) A 3.7 Mb deletion encompassing ZEB2 causes a novel polled and multisystemic syndrome in the progeny of a somatic mosaic bull. PLoS One 7, e49084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltman D.W. & Pemberton J.M. (2004) Inheritance of coat colour and horn type in Soay sheep In: Soay Sheep: Dynamics and Selection in an Island Population (Ed by Clutton‐Brock T.H. & Pemberton J.M.), pp. 321–7. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- De Moor C.H., Meijer H. & Lissenden S. (2005) Mechanisms of translational control by the 3'‐UTR in development and differentiation. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology 16, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolling C.H.S. (1961) Hornedness and polledness in sheep. IV. Triple alleles affecting horn growth in the Merino. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 12, 353–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dominik S., Henshall J.M. & Hayes B.J. (2012) A single nucleotide polymorphism on chromosome 10 is highly predictive for the polled phenotype in Australian Merino sheep. Animal Genetics 43, 468–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston S.E., Beraldi D., McRae A.F., Pemberton J.M. & Slate J. (2010) Horn type and horn length genes map to the same chromosomal region in Soay sheep. Heredity 104, 196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston S.E., McEwan J.C., Pickering N.K., Kijas J.W., Beraldi D., Pilkington J.G., Pemberton J.M. & Slate J. (2011) Genome‐wide association mapping identifies the genetic basis of discrete and quantitative variation in sexual weaponry in a wild sheep population. Molecular Ecology 20, 2555–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston S.E., Gratten J., Berenos C., Pilkington J.G., Clutton‐Brock T.H., Pemberton J.M. & Slate J. (2013) Life history trade‐offs at a single locus maintain sexually selected genetic variation. Nature 502, 93–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund A., Knudsen S.M., Vissing H., Clark B. & Tommerup N. (1996) Assignment of human elongation factor 1alpha genes: EEF1A maps to chromosome 6q14 and EEF1A2 to 20q13.3. Genomics 36, 359–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medugorac I., Seichter D., Graf A., Russ I., Blum H., Göpel K.H., Rothammer S., Förster M. & Krebs S. (2012) Bovine polledness ‐ an autosomal dominant trait with allelic heterogeneity. PLoS One 7, e39477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery G.W., Henry H.M., Dodds K.G., Beattie A.E., Wuliji T. & Crawford A.M. (1996) Mapping the Horns (Ho) locus in sheep: a further locus controlling horn development in domestic animals. Journal of Heredity 87, 358–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opdenakker G., Cabeza‐Arvelaiz Y., Fiten P. et al (1987) Human elongation factor 1 alpha: a polymorphic and conserved multigene family with multiple chromosomal localizations. Human Genetics 75, 339–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pailhoux E., Vigier B., Chaffaux S. et al (2001) A 11.7‐kb deletion triggers intersexuality and polledness in goats. Nature Genetics 29, 453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M.R., Pilkington J.G., Clutton‐Brock T.H., Pemberton J.M. & Kruuk L.E. (2006) Live fast, die young: trade‐offs between fitness components and sexually antagonistic selection on weaponry in Soay sheep. Evolution 60, 2168–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothammer S., Capitan A., Mullaart E., Seichter D., Russ I. & Medugorac I. (2014) The 80‐kb DNA duplication on BTA1 is the only remaining candidate mutation for the polled phenotype of Friesian origin. Genetics Selection Evolution 3 46, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak E. & Gebauer F. (2013) Translational control by 3'‐UTR‐binding proteins. Briefings in Functional Genomics 12, 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemar N., Tetens J., Jagannathan V., Menoud A., Neuenschwander S., Bruggmann R., Thaller G. & Drögemüller C. (2014) Independent polled mutations leading to complex gene expression differences in cattle. PLoS One 9, e93435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson T.N., Speed T.P., Tregear G.W. & Bathgate R.A. (2005) Evolution of the relaxin‐like peptide family. BMC Evolutionary Biology 5, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Primers used for detection of the sheep polled mutation.

Figure S1 Sequences of horned and polled sheep.