Abstract

Cardiopulmonary diseases are major causes of death worldwide, but currently recommended strategies for diagnosis and prevention may be outdated because of recent changes in risk factor patterns. The Swedish CArdioPulmonarybioImage Study (SCAPIS) combines the use of new imaging technologies, advances in large‐scale ‘omics’ and epidemiological analyses to extensively characterize a Swedish cohort of 30 000 men and women aged between 50 and 64 years. The information obtained will be used to improve risk prediction of cardiopulmonary diseases and optimize the ability to study disease mechanisms. A comprehensive pilot study in 1111 individuals, which was completed in 2012, demonstrated the feasibility and financial and ethical consequences of SCAPIS. Recruitment to the national, multicentre study has recently started.

Keywords: cardiovascular, epidemiology, metabolism, pulmonary, trial design

Objective

The Swedish CArdioPulmonary BioImage Study (SCAPIS) was initiated as a major joint national effort in Sweden to reduce mortality and morbidity from cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and related metabolic disorders, all of which are important issues for public health. Its main goal was to characterize, in terms of phenotype and environmental and socio‐economic influences, a Swedish cohort of 30 000 men and women aged 50–64 years to obtain novel information that is relevant in today's environment to identify and treat individuals with cardiopulmonary and metabolic diseases and to optimize the ability to investigate disease mechanisms (see Table 1). SCAPIS capitalizes on the latest developments in imaging that enable direct investigation of subclinical disease in multiple organs and vascular beds. In addition, innovative use of large‐scale genotyping and recent developments in metabolomics and proteomics will facilitate the identification of new biomarkers and mechanisms for disease.

Table 1.

Principal aims of SCAPIS

| To use advanced imaging methods to examine atherosclerosis in the coronary and carotid arteries together with information obtained by proteomics/metabolomics/genomics technologies to improve risk prediction for CVD |

| To use advanced imaging methods to examine pulmonary tissue in combination with functional measurements and information obtained by proteomics/metabolomics/genomics technologies to improve diagnosis and risk prediction for COPD |

| To use advanced imaging methods to examine fat deposits together with information obtained by proteomics/metabolomics/genomics technologies to improve understanding of the role of obesity and diabetes in CVD and COPD |

| To improve the understanding of the epidemiology of CVD and COPD |

| To improve the understanding of underlying mechanisms of disease in CVD and COPD |

| To evaluate the cost‐effectiveness and ethics of using new imaging methods and proteomics/metabolomics/genomics technologies in prevention of CVD and COPD |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Background

The recent decline in mortality and morbidity from CVD in Western societies 1, 2 has been mostly attributed to reductions in smoking and plasma cholesterol levels related to lifestyle changes in the population but also to new treatments and improved management of acute myocardial infarction 3, 4. A parallel decrease in histological features of atherosclerotic plaques that are currently considered important for plaque instability has also been observed 5. However, despite these improvements, CVD remains a major threat to public health and accounts for almost 40% of all deaths 6, 7, 8. The first symptom of coronary atherosclerosis is often sudden death or acute coronary syndrome 9, and 75% of fatal coronary events occur outside the hospital in patients with first ever myocardial infarction 10, 11, indicating the importance of improving identification of asymptomatic high‐risk individuals. Furthermore, it is anticipated that the increasing frequency of metabolic risk factors such as obesity, dyslipidaemia and diabetes 12, 13, 14 will soon offset the decline in CVD seen in recent decades 15, 16. Accumulating evidence indicates that obesity, particularly with an ectopic distribution of fat in the abdomen, muscles, liver and pericardium, represents an important new risk factor and plays a pivotal role in the development of atherosclerosis by increasing levels of pro‐atherosclerotic lipoproteins and inflammatory mediators 13, 17.

Although COPD is the third most common cause of death worldwide 18, its impact has not been fully recognized by policy makers. Recent diagnostic tests have identified a number of phenotypes, indicating that COPD is not a single entity 19. In the industrialized world, the most important risk factor for COPD is tobacco smoking, but environmental and occupational exposure to pollutants may also play an important role 20; 5–10% of all COPD cases occur in never‐smokers, with the majority of cases amongst nonsmokers occurring in women 21. Despite progress in the management of COPD in recent years, the prevalence of and mortality due to this condition remain high 22, 23. Many subjects live for years with COPD both before and after diagnosis, which results in substantial disability in the population at a high cost to society 24. Patients with COPD have an increased risk of CVD independent of known CVD risk factors, which has prompted suggestions that these diseases develop through similar mechanisms 25, 26, 27. Abdominal obesity has been identified as a key determinant of the association between the metabolic syndrome and lung function impairment 28.

With modern imaging techniques, it is now feasible to directly visualize early preclinical signs of vascular and pulmonary disease. Computed tomography (CT) can detect and quantify fat deposits within and around different organs 29. High‐resolution ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and coronary CT angiography (CCTA) can identify and characterize subclinical atherosclerotic disease in most vascular beds 30, 31, 32, 33. Multidetector CT (MDCT) of the lungs can detect and stage early signs of pulmonary disease, including emphysema and airway wall thickening 34. These techniques are used in SCAPIS to obtain information that can be applied to improve risk management and explore disease causes. Increased understanding of the underlying mechanisms will facilitate and improve prevention and prediction of prognosis, and result in novel and better‐tailored treatment of CVD, COPD and associated metabolic diseases.

SCAPIS design

SCAPIS is designed as a prospective observational study of a randomly selected sample from the general population. The examinations were selected on the basis of their ability to provide detailed phenotypic information on subclinical disease whilst at the same time being applicable for use in a large study population. The design of the study has been tested in a pilot population.

Study population

The aim was to recruit 30 000 subjects aged 50–64 years randomly selected from the Swedish population register. Subjects are recruited and examinations performed at six Swedish university hospitals (Gothenburg, Linköping, Malmö/Lund, Stockholm, Umeå and Uppsala), each site recruiting 5000 individuals from the respective municipality areas. Recruitment is continuously monitored with respect to sex and age distribution (50–54, 55–59 and 60–64 years). Calculations of the number of incident cases and future CVD and COPD events based on the results from the pilot study confirm that the size of the study allows for relevant subgroup analyses.

Recruitment

All Swedish residents have a unique personal identification number (PIN), which allows unbiased and randomized recruitment from the Swedish population register, almost complete follow‐up, and linkage to registries with information on hospitalizations, living conditions and social welfare (www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistics, www.scb.se/en_/). Initial contact is made by sending out an informational brochure asking the recipient to contact the study centre via telephone, e‐mail or letter. If the centre is not contacted, the recipient is reminded by up to three telephone calls (including one in the evening) and finally by letter. If the centre is contacted and the subject is willing to participate in the study, an appointment is arranged at the study centre. No exclusion criteria are applied except the inability to understand written and spoken Swedish for informed consent. No reimbursement is provided for travel expenses or loss of income. To improve recruitment, the study is advertised in local newspapers and on television. Employers in the catchment areas are targeted to encourage study participation with paid leave.

Virtual cohort

In parallel with the recruitment process, virtual cohorts will be constructed consisting of register‐based census data on hospitalizations, income, education and ethnicity in subjects aged 50–64 years in the catchment areas. The virtual cohorts will be used to gauge the representativeness of the recruited sample compared to the background population.

Examinations and informed consent

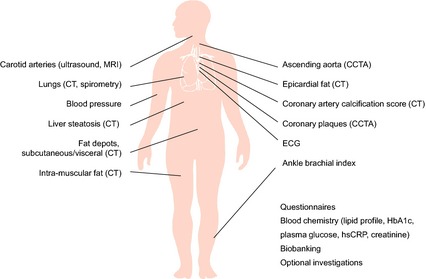

The examinations are performed on two or three occasions within a 2‐week period dependent on logistics at each study site. Core examinations that are common for all sites are performed as well as optional examinations at one or more sites depending on the local research interest (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the information collected from the subjects in SCAPIS. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; ECG, electrocardiogram; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein.

Detailed informed consent is collected from each participant as the first procedure on the first visit.

Questionnaires

A questionnaire, comprising 140 questions separated into sets relating to factors central to the research aims, has been designed to collect detailed information on self‐reported health, family history, medication, occupational and environmental exposure, lifestyle, psychosocial well‐being, socio‐economic status and other social determinants. A food‐frequency questionnaire (Mini‐Meal‐Q) with 35 questions is also used 35.

Biochemistry and biobank storage

A venous blood sample (100 mL) is collected from participants after an overnight fast and is used for immediate analysis and stored in a biobank for later analysis (cholesterol, HDL, triglycerides, calculated LDL, plasma glucose, HbA1c, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein and creatinine). If plasma glucose is ≥7.0 mmol L−1, a repeat sample is taken at the second visit to establish a potential diagnosis of diabetes 36. Blood and spot urine samples for biobank storage are processed in accordance with guidelines from the Swedish Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (BBMRI.se/en/). Further details are provided in the Supporting Information.

Anthropometry, electrocardiography, blood pressure and accelerometry

Body weight is measured on a balance scale with subjects dressed in light clothing without shoes. Body height, waist and hip circumference are also measured according to current recommendations 37. A 12‐lead standard electrocardiogram is recorded in the supine position after a rest for 5 min. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures are measured twice in each arm with an automatic device (Omron M10‐IT, Omron Health care Co, Kyoto, Japan) and the mean of the measurements used. The ankle–brachial index 38 is measured as described in the Supporting Information. Between visits, the participants are equipped with an accelerometer (Actigraph Activity Monitor GT3X‐BT Actigraph, Pensacola, Florida, US) to be worn on the hip to register ambulatory activity for 7 days.

Lung function tests

Dynamic spirometry (Jaeger MasterScreen PFT, Carefusion, Hoechberg. Germany) is performed according to the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study protocol 39 to measure forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and slow vital capacity. Spirometry is performed 15 min after the inhalation of 400 μg salbutamol. Gas diffusing capacity is measured using a single‐breath carbon monoxide diffusion test (Jaeger MasterScreen PFT) according to American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society recommendations 40.

Imaging carotid arteries with ultrasound and MRI

Atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries is imaged using a standardized protocol with a Siemens Acuson S2000 ultrasound scanner equipped with a 9L4 linear transducer (both from Siemens, Forchheim, Germany). The two‐dimensional greyscale ultrasound image is analysed to determine intima–media thickness, plaque size and number of plaques and to differentiate between homogenous and heterogeneous plaque structures and plaques with different echogenicity 32, 41.

Participants with moderate‐to‐large plaques in the carotid arteries (plaque height exceeding 2.5 mm) are asked to return for a third visit to undergo MRI scanning. The MRI procedure is designed to optimize imaging of the following plaque characteristics: size of lipid‐rich necrotic core, thickness of fibrous cap, presence of intraplaque haemorrhage, calcifications and plaque volume 42 (see Supporting Information).

Imaging with CT

CT is performed using a dedicated dual‐source CT scanner equipped with a Stellar Detector (Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens Medical Solution, Forchheim, Germany). A standardized sequential image acquisition work‐flow has been developed to allow the heart, lungs and fat depots to be imaged in one session (see Supporting Information).

Coronary arteries

The calcium content in each coronary artery is measured and summed to produce a total coronary artery calcification score (CACS) according to international standards 43.

Subjects without contraindications to contrast media receive an intravenous beta‐blocker to reduce heart rate (preferably to below 60 beats min−1), sublingual nitroglycerin to induce vasodilatation and an intravenous contrast injection. CCTA is then performed to assess lumen obstruction caused by plaques. The morphology of calcified and noncalcified plaques as well as remodelling of lumen geometry can be assessed; this information is not provided by conventional intra‐arterial angiography 31, 44. CCTA has high inter‐ and intra‐observer agreement in detecting calcified plaques and greater variability in detecting noncalcified plaques 45.

Lung tissue

Early structural changes in lung tissue are imaged by MDCT over the full lung volume. This provides information about airway wall thickness and emphysema which is essential in the phenotyping of COPD.

Fat depots

To investigate the association between disease and fat distribution including ectopic fat accumulation, CT is used to image epicardial, subcutaneous, intra‐abdominal, intramuscular and intrahepatic fat deposits. The liver is also imaged using dual‐energy CT to further characterize the tissue 46 (see Supporting Information).

Optional examinations

Each regional site is allowed to include optional examinations that will not interfere with or affect the core examinations but will allow each site to expand on its own research interests. Examples include collection of faecal samples for mapping of the gut metagenome, sleep apnoea measurements, three‐dimensional electrophysiology, fitness testing, oral glucose tolerance testing and whole‐body plethysmography.

Handling of data and images

Study data will be entered into a central database at the study site through electronic case report forms. Collaboration between SCAPIS and the Western Sweden Regional Image database (‘Bild och Funktionsregistret’, Gothenburg, Sweden) will enable images generated within SCAPIS to be available both to healthcare providers for clinical follow‐up and to research groups across Sweden.

Follow‐up and use of epidemiological databases

Participants will be monitored for future events through annual extensive register searches by linking the unique Swedish PINs to the Swedish National Hospital Discharge Register and the Swedish Cause of Death Register, facilitated by the detailed informed consent obtained at the first visit. End‐points include fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous coronary interventions or death from coronary heart disease; incident cases of stroke defined according to World Health Organization criteria 47 (subtypes of stroke are classified as cerebral infarction, intracerebral haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage); heart failure and atrial fibrillation identified from a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis in the Swedish National Hospital Discharge Register; respiratory events defined as first‐time hospitalization for COPD, pneumonia and respiratory insufficiency; and all‐cause death. There will also be a questionnaire‐based follow‐up after 3–5 years that will mainly focus on outcomes not captured in registers, including symptoms and diseases such as asthma and rhinitis.

High external validity has been demonstrated for myocardial infarction and heart failure identified through registers 48. To increase the quality of reporting, local clinical events committees at each site will adjudicate all end‐points retrieved from the Swedish National Hospital Discharge Register and the Swedish Cause of Death Register based on the information from secondary searches in local hospital registers. The Swedish prescribed drug register will provide data on dispensed prescriptions. Data from high‐quality, national registers on CVD and pulmonary disease (e.g. SWEDEHEART 49, Riks‐STROKE 50 and SWEDVASC 51) will provide detailed information on the type of event and interventions used. A range of other registers is also available with detailed information, for example, on living conditions, salary, education and social welfare (see Supporting Information).

Ethical aspects

SCAPIS has been approved as a multicentre trial by the ethics committee at Umeå University and adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Radiation for imaging

With current imaging modalities, the dose of radiation can be kept low (see pilot data). Evidence from our pilot data indicates that SCAPIS will lead to the early detection of many more cancers than those caused by the additional radiation dose. In addition, multi‐organ imaging will facilitate the detection of other diseases and lead to early treatment. Furthermore, we anticipate that the large amount of information that will result from imaging in SCAPIS will lead to many new scientific discoveries. The radiation safety committee at each hospital has carefully weighed the potential benefits against the potential harm induced by radiation exposure (mainly radiation‐induced lung cancer in the age group considered) and deemed that the radiation dose is justifiable for the SCAPIS population. The SCAPIS steering committee has also considered radiation safety (see Supporting Information).

Medication for imaging

The iodinated contrast agent used for CCTA has the potential to cause renal damage 52, but the frequency of contrast‐induced nephropathy is debated; very few high‐quality studies have been conducted 52, 53, 54, and from a recent large study, it was concluded that contrast material is not associated with increased risk 55. No hospitalizations for renal failure were reported in the pilot trial. However, we will prospectively monitor renal function in the next phase of SCAPIS, using repeated creatinine measurements in a selected population, to investigate the impact of iodinated contrast agents on subtle functional changes.

Pathological findings and their consequences

Because the study design involves very detailed phenotyping of the subjects, many potentially relevant clinical findings related to cardiopulmonary disease will be identified (see pilot data). Established treatment strategies will exist for some but not all of these findings 56. Working groups have thus been created to establish a consensus recommendation on how to deal with the most common clinical findings. These groups comprise expert representatives from cardiology, oncology, radiology and respiratory medicine from the participating university hospitals. All subjects receive information about potential risk factors for disease and any findings that require further investigations and treatment (see pilot data). All advice given is standardized to achieve a similar follow‐up at all sites. The information is routinely accompanied by written advice on changes to promote a healthier lifestyle. However, subjects are clearly informed that no information is revealed about data of uncertain clinical value or data collected solely for future research purposes (e.g. genetic or detailed ‘omics’ data).

Data held within the research database are confidential, never revealed to any external sources and only used in coded format. However, the participants are informed that pathological findings in need of follow‐up in the healthcare system are documented in the hospital's ordinary patient records. Access to this information is controlled by the hospital and treating physicians, not the study organization, and is normally confidential. However, an insurance company has the right to request medical information from, or authorization to access the medical records of, a person who wants to take out life insurance. If data are revealed to an insurance company, they may affect the circumstances for obtaining life insurance.

Quality assurance

Quality at all stages of SCAPIS is essential for the safety of the participants and to obtain valid data. Therefore, all questionnaires, examinations, management of clinical data, data handling, automated data validation, participant information and laboratory techniques are based on the established methods and standard operating procedures (including staff training). National or regional core facilities are used for storing samples and images. Regular training sessions (three to four times per year) are scheduled for all staff. Images for scientific use will be read prospectively by the radiologists in each radiology department. Reproducibility of these readings will be published and assured by regular national training sessions and consensus discussions. Core laboratories will also be used for secondary reading of CT (fat depots, pulmonary imaging and CCTA) and ultrasound images (intima–media thickness and plaque size and texture).

Study data are entered into a central database at the study site through an electronic case report form. Integrity of the data and efficiency of recruitment will be continuously monitored by a central data‐monitoring group.

National study organization

SCAPIS is led by a steering committee comprising representatives from and endorsed by the six participating universities. The steering committee has the overall scientific and fiscal responsibility for SCAPIS. Each university representative will organize a local steering group with competence in cardiology, respiratory medicine and radiology. A scientific advisory board comprising distinguished national and international researchers has been appointed. After collection of data, SCAPIS will be open to national and international researchers after application to and subsequent approval by the steering committee.

SCAPIS pilot trial

The pilot trial of SCAPIS was performed in the city of Gothenburg, Sweden, from February to November 2012. Its primary aims were to examine the feasibility of the study design and to estimate the consequences of pathological findings identified during the examinations on clinical resources within the public healthcare system and on the participants from an ethical perspective. The only difference from the design of the main study outlined above was that participants were recruited from areas with high versus low socio‐economic status, which allowed us to examine participation rates and reasons for nonparticipation. In total, 1111 subjects were recruited (of 2243 invited) and all main aspects of the SCAPIS design were tested. The planned time schedule was adhered to, thus verifying the feasibility of examining 5000 subjects in 3 years at one site.

Participation rates

The overall participation rate was 49.5% (39.9% and 67.8% in areas of low and high socio‐economic status, respectively). Reasons for nonparticipation were as follows: inability to make contact with the subject (37.4%), too busy (15.7%), too sick (6.6%), language difficulties (7.8%), miscellaneous (6.4%) and none given (26.1%). Lack of contact and language difficulties dominated in areas of low socio‐economic status.

Proportion of participants with complete examinations

At least one aliquot of blood was stored and biobanked from 99.6% of the participants, and complete sets of samples were obtained from 93.0%. The questionnaire was completed by 97.7% of the participants, spirometry was performed in 99.5% and complete sets of noncontrast CT images were available from 98.0%. CCTA was performed in 88.2% of the participants.

Radiation dose

The median effective radiation dose used for the comprehensive CT imaging was 4.2 mSv, divided between cardiac (2 mSv for CACS and CCTA combined), pulmonary (2 mSv) and metabolic imaging (0.2 mSv). Ethical considerations for an acceptable radiation dose are discussed in detail in the Supporting Information.

Pathological findings and their consequences

Risk factor patterns were as expected in the population with a high prevalence of dyslipidaemia, hypertension and obesity (Table 2). Previous CVD was not common (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants observed in the SCAPIS pilot trial and predicted in the future total cohort

| SCAPIS pilot n = 1111 | Predicted in total SCAPIS cohorta n = 30 000 | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n | |

| Previous CVD (MI, stroke) | 27 (2.4) | 750 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 27 (2.4) | 750 |

| Dyslipidaemia (total) | 289 (26) | 7800 |

| Dyslipidaemia (treated) | 103 (9) | 2790 |

| Hypertension (total) | 370 (33) | 10 200 |

| Hypertension (treated) | 249 (22) | 6600 |

| Diabetes | 87 (8) | 2340 |

| Current smoking | 200 (18) | 5400 |

| Obesity (BMI >30 kg m−2) | 244 (22) | 6600 |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index.

Previous CVD, atrial fibrillation, hypertension and diabetes data are based on self‐reported health (questionnaire or interview) in combination with laboratory results. Obesity data are derived from direct measurements.

Extrapolation of pilot data to obtain predicted number of participants with different conditions in the total SCAPIS cohort.

The study examinations led to the early diagnosis of three malignant tumours (one hepatocellular carcinoma and two pulmonary adenocarcinomas) and one thoracic aortic aneurysm (6 cm wide), all of which have been treated. As expected, the most common incidental findings were pulmonary nodules, which were managed according to recent recommendations 57. All participants with significant coronary stenosis in critical vascular segments (>50% lumen obstruction in the main stem or proximal left anterior descending artery, three‐vessel disease or CACS of >400) were referred to a cardiologist for relevant management according to a common standardized algorithm written for SCAPIS by a national expert group of cardiologists. All participants with CVD risk factors and newly diagnosed diabetes and/or hypertension were given written recommendations for follow‐up and, if necessary, encouraged to make an appointment with their primary healthcare provider.

Perception of risk

From an ethical perspective, the pilot trial revealed that information on risk and the possibility of suffering from disease was perceived very differently by individual participants. To handle this issue, a number of changes were made to the informed consent form and to the information given to the participants. In addition, a research programme has been launched within SCAPIS to develop instruments that will increase our understanding of how information is perceived by and best delivered to the participants 58.

Financial projections

The experience and results from the pilot study allowed precise estimates of the financial costs of running the full study at each site as well as the resources needed from the healthcare organizations to manage detected disease.

Expected event rates calculated from SCAPIS pilot trial data

We used information (age, sex, systolic blood pressure, HDL and cholesterol) from the CVD‐free subgroup of subjects (no prevalent stroke or myocardial infarction) enrolled in the pilot trial (n = 1074) and calculated their future risk of CVD using information on event rate from four different independent risk algorithms 59, 60, 61, 62, 63. We also extracted information on incidence rate from two separate Swedish cohort studies (see Supporting Information). The average incidence rate from these six values was used to calculate the number of events expected to occur in the total SCAPIS cohort. These estimates were then recalculated to predict incident cases of fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction and stroke as outlined in the Supporting Information. Based on these calculations, we predict that approximately 190 CVD end‐points will occur (i.e. incident cases of nonfatal or fatal myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke) in our cohort of 30 000 subjects within a period of 2 years. At 5 years, there will be nearly 600 events and at 10 years more than 1600 events. In addition, we predict that 120 hospitalizations due to COPD exacerbations and up to 500 COPD exacerbations treated on an outpatient basis will occur in our cohort of 30 000 subjects within a period of 2 years (see Supporting Information).

Because the incidence of CVD, COPD and related metabolic diseases will show large variations dependent on age and sex, socio‐economic status, presence of clinical disease and other risk factors, the size of the study is calculated to allow for important subgroup analyses. The number of subjects in the total SCAPIS cohort expected to develop different conditions is shown in Table 2. The cross‐sectional analyses at baseline will allow direct and detailed studies of the associations between subclinical atherosclerotic disease in the carotid and coronary arteries and risk factors including COPD and ectopic fat distribution. Because the age group under study includes individuals who are clinically healthy but with signs of early disease, a clear advantage of cross‐sectional analyses is the minimal confounding effects of concomitant pharmacological risk factor treatment.

Advantages of SCAPIS compared to other similar cohorts

Building on the tradition of early landmark population studies such as the Framingham Heart Study 64, several large international cohort studies have been completed, or are ongoing or planned, focusing on CVD and COPD 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72. There are also a number of very large ongoing epidemiological initiatives that aim to cover all disease areas and therefore are less specific in their design 73, 74, 75. However, the strength of these studies is their size. Compared with these studies, SCAPIS has the advantage that it combines size with extensive and in‐depth phenotyping and direct imaging of the disease process.

In a few large‐scale international studies, for example the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, the Dallas Heart Study and the BioImage study, extensive cardiovascular and pulmonary imaging has been performed (Table 3) 76, 77, 78. However, the planned size of SCAPIS is almost three times that of the next largest study. Further advantages of SCAPIS include (i) it is the only study using CCTA in the total cohort, which allows direct visualization and quantification of plaques in the coronary arteries; (ii) direct visualization of disease in lung and vessels is combined with detailed metabolic imaging of fat depots on a scale not attempted in any other study; and (iii) an unbiased and randomly selected sample is recruited from the general population. Furthermore, the Swedish identification number and registers provide advantages in selection of the cohort and follow‐up. In addition, because the prevalence of smoking in Sweden is relatively low (18% in the SCAPIS pilot), it is feasible to perform subgroup analyses on never‐smokers.

Table 3.

Comparison of large population‐based imaging studies

| MESA 76 | Dallas heart study 77 | BioImaging 78 | SCAPIS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | 2000 | 2002 | 2008 | 2014 |

| Completion | 2002 | 2004 | 2009 | 2018 |

| Age group (years) | 45–84 | 18–65 |

Men >55–80 Women >60–80 |

50–64 |

| Sample size | 6814 (53% women) | 3072 (55% women) | 6101 (56% women) | 30 000 (50% women) |

| Exclusion criteria | Known CVD, treated cancer | None | Claims of CVD, cancer, etc. | None |

| Population | Stratified for ethnicity | Probability sampling (postal addresses); stratified for ethnicity | Members of Humana Health Plan; stratified for ethnicity | Random population sample |

| Participation rate (%) | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

49 (pilot data) |

| Imaging | ||||

| Atherosclerosis | ||||

| Carotid – ultrasound | 6814 | – | 6104 | 30 000 |

| Carotid – MRI | – | – | 525 | 3000 |

| Coronary artery calcium | 6814 | 2971 | 6104 | 30 000 |

| Coronary plaque | – | – | 380 | 27 000 |

| Pulmonary | ||||

| MDCT | – | – | – | 30 000 |

| Metabolic | ||||

| Liver | 6814 | 2971 | – | 30 000 |

| Epicardial/abdominal/thigh | 6814 | 2971 | – | 30 000 |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; MDCT, multidetector computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Advantages of using CT in population studies of cardiopulmonary disease

A number of imaging modalities can be used to visualize vascular and pulmonary disease. However, because of their invasive nature, radiation burden or length of time required for image acquisition, many of these techniques are not applicable for use in a large population study with healthy volunteers. There are four main reasons for the choice of CT for imaging in SCAPIS: (i) imaging of the coronary circulation, lungs and fat depots can be done in the same session; (ii) fast image acquisition allows high throughput of subjects; (iii) if contrast media is injected, noninvasive assessment of the coronary circulation and plaque disease is possible; and (iv) all of the above can be achieved with acceptable doses of radiation if the most recently developed hardware and software are used.

CACS

CT has been used frequently in population studies to detect coronary arterial calcifications, and CACS has been shown to improve the identification of individuals at high risk of CVD. In the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, CACS was a strong predictor of cardiovascular and coronary events and improved the C statistic (equivalent to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve) from 0.77 (with traditional risk factors) to 0.81 79. Similarly, in the Rotterdam Study, CACS raised the C statistic for coronary events from 0.72 to 0.76 80. CACS has also been shown to improve risk classification in intermediate‐risk individuals. In the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, calcium scores reclassified 55% of intermediate‐risk individuals, including 16% who were upgraded to high risk 81. The overall net reclassification improvement (NRI) was 25%. In the Rotterdam Study, 52% of intermediate‐risk individuals were reclassified, 22% to high risk and the overall NRI was 14% 80. Similar results were obtained in another large population‐based cohort, the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study 82. Thus, the use of CACS is an established technique for improved risk classification. However, its use is not yet recommended for screening of low‐risk populations and is controversial for those at intermediate risk 83, 84, 85. If the incremental value of CACS can be improved by combination with new biomarkers of disease, these recommendations may be revised.

CCTA

At present, no large population studies have published CCTA data from a randomly selected healthy population. Current knowledge of the prognostic potential of CCTA comes from studies of patients assessed with CCTA because of suspected CVD and cardiovascular symptoms. These studies have shown that the degree of stenosis and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis in terms of number of diseased vessels predict mortality 86, 87. Several studies using invasive angiography or CCTA have shown that proximal are more relevant than distal diseased segments for prognosis 87, 88, 89. The large multinational CONFIRM registry, comprising over 20 000 patients with suspected clinical cardiac disease, confirmed the predictive value of segmental plaque burden beyond the degree of stenosis 30. By focusing only on plaques in the proximal segments, the predictive value of CCTA could be improved significantly; the best CCTA parameters to improve outcome beyond clinical risk scores were proximal segments with >50% stenosis 30.

In addition to plaque burden, CCTA‐derived plaque features that appear to identify a high‐risk population include low attenuation plaques, outward remodelling 31 and the ‘ringlike sign’ that is thought to correspond to the presence of a thin‐cap fibroatheroma 44, 90. In a recent study, it was shown that these signs of plaque vulnerability are associated with future acute coronary syndrome events even when the plaques are physiologically nonobstructive as evidenced by a negative stress test 44. These studies thus indicate that coronary plaque vulnerability is determined by factors beyond the degree of stenosis and that CCTA‐derived information on plaque characteristics will improve risk prediction beyond calcium scoring.

CT‐derived information on coronary disease will be combined in SCAPIS with extensive biomarker programmes and detailed phenotyping to identify high‐risk plaque features and expand the understanding of plaque biology.

Possibilities for data analyses to identify gene–metabolite–disease interactions

SCAPIS is an ideal cohort to identify gene–metabolite–disease interactions by combining the extensive phenotyping data with metabolomic/lipidomic, proteomic and genetic analyses. For example, we will test the hypothesis that interplays between dietary intake and genetic composition generates metabolic signatures that in turn are likely to be causally related to the development of myocardial infarction. In an attempt to identify such metabolic signatures, plasma will be analysed (by liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry) from a subgroup of SCAPIS participants after an overnight fast. Using a Mendelian randomization approach 91, 92, we will investigate whether there is a causal association between specific metabolite alterations and genetic variation using genomewide association studies and exome chip analysis. Associations between metabolites/metabolic pathway‐related metabolite patterns and the presence of severe coronary atherosclerosis at baseline will also be investigated as well as the incidence of myocardial infarction during follow‐up. To test whether such relationships are causal or only parallel phenomena, our findings will be validated by identifying genetic variants strongly associated with the plasma concentration of the particular metabolite/metabolic pathway. Such metabolite‐associated gene variants will then be tested for association with the presence of coronary atherosclerosis/incidence of myocardial infarction in the entire SCAPIS population. Gene–metabolite–disease interactions that can be validated in such a three‐stage procedure would imply a causal relationship between the metabolite/metabolite patterns and the presence of disease and suggest a potential drug and lifestyle‐modifiable target for disease prevention.

Limitations

An important aim in the recruitment process is to ensure a reasonably high participation rate 93. High participation rates have been increasingly difficult to achieve in recent years, exemplified by the steady decline in rates observed in the repeated studies of 50‐year‐old men in Gothenburg, Sweden 94. The recruitment strategy used in the pilot study was designed to quantify and describe the anticipated recruitment difficulties from different social strata. As expected, a large difference in participation rates was seen between more and less affluent areas in Swedish society (67% vs. 37%) despite an overall acceptable participation rate of 49%. Financial restraints limit the study to those who understand written and spoken Swedish. This will mean that some immigrants are excluded, thus limiting the generalizability of SCAPIS to these groups in society. Nevertheless, the pilot study clearly demonstrated substantial differences in health associated with socio‐economic status in Swedish society. Furthermore, the pilot study showed that subjects at risk of disease from less affluent areas will participate in the study, albeit at a lower level than those from affluent areas. Given that SCAPIS will comprise 30 000 individuals, its size will be sufficient to overcome this limitation and allow important comparisons to be made between social strata.

Despite the pilot study experience from Gothenburg showing socio‐economic differences in risk factors, we chose to recruit subjects based on a randomized selection of participants from the Swedish population register without stratification for socio‐economic status. The main reason for this decision is that smaller socio‐economic gradients are anticipated at the smaller university sites (Umeå, Linköping and Uppsala) compared to the larger cities (Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö). The gradients will also be qualitatively different between cities, making controlled stratification impossible. In addition, the unique Swedish PIN and availability of detailed registers (with extensive records of hospitalizations, census information, education, employment, sick leave, social welfare and income) will allow us to quantify and statistically compensate for variations in participation rate. Virtual cohorts with the same background as those in the randomized sample will be created, which will enable us to analyse and account for the effects of nonparticipation on both disease and social class.

Conclusion

SCAPIS will create a unique Swedish cohort for studies on CVD, COPD and related metabolic disorders at the highest international level, which will increase knowledge of basal mechanisms and improve risk prediction of these diseases and might lead to more individualized, cost‐effective and better health care. Prevention of premature CVD and COPD is a high priority worldwide, and we anticipate that better risk discrimination will lead to more cost‐effective measures. The size and design of SCAPIS will ensure the ability to statistically account for age, sex and other confounding factors and provide the possibility to study subpopulations with high statistical power. The pilot study has convincingly shown that the protocol with its extensive imaging is feasible, and the planned timescale is realistic.

The creation of an extensive blood and DNA biobank will greatly facilitate the search for new lipid, protein and genetic biomarkers of disease. Once established, the platform will provide the basis for cutting‐edge translational and reverse translational research within gene–environment interaction studies and case–control or case–cohort studies of mechanisms underlying CVD, COPD and related metabolic disorders.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflicts of interest to declare. The manuscript has been handled by an external editor, Professor Sam Schulman, Mac Master University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Supporting information

Table S1. Number of aliquots proposed for delivery to the national biobank resource.

Table S2. Sequences used for magnetic resonance imaging.

Table S3. Details of settings and protocols used for computed tomography in SCAPIS.

Table S4. Epidemiological registers that will be used in SCAPIS.

Table S5. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in women and men free from cardiovascular disease at the baseline examination in the SCAPIS pilot trial.

Table S6. Risk of cardiovascular events in the next 10 years in the SCAPIS pilot trial estimated using four independent risk calculators with risk factors from Table S5.

Table S7. Incidence rate of coronary and stroke events in the Malmö Diet and Cancer study 8.

Table S8. Incidence rate of coronary and stroke events in a registry‐based cohort of men and women living in the city of Gothenburg.

Table S9. The predicted number of accumulated events at 2, 5 and 10 years after study completion.

Figure S1. The algorithm used in SCAPIS to identify subjects for whom administration of contrast medium could pose a risk. eGFR, glomerular filtration rate estimated from the serum creatinine level.

Figure S2. Mortality from ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke in Sweden as a function of age (data from the National Board of Health and Welfare).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Rosie Perkins (Wallenberg Laboratory, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg) for expert editing, Helén Milde and Marit Johannesson (radiology nurses at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg) for excellent work on the CT protocols, Petter Quick (radiology nurse at the Center for Medical Image Science and Visualization, Linkoping University) for helpful advice on protocol application, Bim Boberg (Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation) and Sven‐Anders Benjegård (Gothia Forum, Gothenburg) for expert project management and Anna Sjöström (Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation) for artwork (Fig. 1) The baseline examination of SCAPIS is supported in full by the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation throughout the planning phase and realization of the study; the study is also funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Swedish Research Council and VINNOVA (Sweden's innovation agency).

Bergström G, Berglund G, Blomberg A, Brandberg J, Cederlund K, Engström G, Engvall J, Eriksson M, de Faire U, Flinck A, Hansson MG, Hedblad B, Hjelmgren O, Janson C, Jernberg T, Johnsson Å, Johansson L, Lind L, Löfdahl C‐G, Melander O, Johan Östgren C, Persson A, Persson M, Sandström A, Schmidt C, Söderberg S, Sundström J, Toren K, Waldenström A, Wedel H, Vikgren J, Fagerberg B, Rosengren A (University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg; Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg; Lund University, Lund; Umeå University, Umeå; Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg; University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg; Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge; Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm; County Council of Östergötland, Linköping; Linköping University, Linköping; Linköping University, Linköping; Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm; Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Karolinska University Hospital; Centre for Research Ethics and Bioethics, Uppsala University, Uppsala; Uppsala University Uppsala; Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge; Uppsala; Uppsala University, Uppsala; Lund University Hospital, Lund; Skåne University Hospital, Malmö; County Council of Östergötland; Umeå University, Umeå; Uppsala Clinical Research Centre, Uppsala; Institute of Medicine, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg; Umeå University Hospital, Umeå University, Umeå; Nordic School of Public Health, Gothenburg, Sweden). The Swedish CArdioPulmonary BioImage Study (SCAPIS): objectives and design. J Intern Med 2015; 278: 645–659.

References

- 1. Wilhelmsen L, Welin L, Svardsudd K et al Secular changes in cardiovascular risk factors and attack rate of myocardial infarction among men aged 50 in Gothenburg, Sweden. Accurate prediction using risk models. J Intern Med 2008; 263: 636–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, Rayner M. European cardiovascular disease statistics 4th edition 2012: EuroHeart II. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bjorck L, Rosengren A, Bennett K, Lappas G, Capewell S. Modelling the decreasing coronary heart disease mortality in Sweden between 1986 and 2002. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 1046–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eriksson M, Holmgren L, Janlert U et al Large improvements in major cardiovascular risk factors in the population of northern Sweden: the MONICA study 1986‐2009. J Intern Med 2011; 269: 219–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Lammeren GW, den Ruijter HM, Vrijenhoek JE et al Time‐dependent changes in atherosclerotic plaque composition in patients undergoing carotid surgery. Circulation 2014; 129: 2269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Socialstyrelsen . Causes of Death 2011. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO . Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control, 2011.

- 8. WHO . Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010, 2011.

- 9. Braunwald E. Acute myocardial infarction–the value of being prepared. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 51–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deo R, Albert CM. Epidemiology and genetics of sudden cardiac death. Circulation 2012; 125: 620–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dudas K, Lappas G, Stewart S, Rosengren A. Trends in out‐of‐hospital deaths due to coronary heart disease in Sweden (1991 to 2006). Circulation 2011; 123: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 2087–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Despres JP, Lemieux I, Bergeron J et al Abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome: contribution to global cardiometabolic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008; 28: 1039–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lilja M, Eliasson M, Eriksson M, Soderberg S. A rightward shift of the distribution of fasting and post‐load glucose in northern Sweden between 1990 and 2009 and its predictors. Data from the Northern Sweden MONICA study. Diabet Med 2013; 30: 1054–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosengren A. Declining cardiovascular mortality and increasing obesity: a paradox. Can Med Assoc J 2009; 181: 127–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Capewell S, Buchan I. Why have sustained increases in obesity and type 2 diabetes not offset declines in cardiovascular mortality over recent decades in Western countries? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2012; 22: 307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dulloo AG, Montani JP. Body composition, inflammation and thermogenesis in pathways to obesity and the metabolic syndrome: an overview. Obes Rev 2012; 13(Suppl 2): 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2095–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carolan BJ, Sutherland ER. Clinical phenotypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma: recent advances. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131: 627–34; quiz 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non‐smokers. Lancet 2009; 374: 733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lamprecht B, Schirnhofer L, Kaiser B, Buist S, Studnicka M. Non‐reversible airway obstruction in never smokers: results from the Austrian BOLD study. Respir Med 2008; 102: 1833–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ford ES, Croft JB, Mannino DM, Wheaton AG, Zhang X, Giles WH. COPD surveillance–United States, 1999‐2011. Chest 2013; 144: 284–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopez‐Campos JL, Ruiz‐Ramos M, Soriano JB. Mortality trends in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Europe, 1994‐2010: a joinpoint regression analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jansson SA, Backman H, Stenling A, Lindberg A, Ronmark E, Lundback B. Health economic costs of COPD in Sweden by disease severity–has it changed during a ten years period? Respir Med 2013; 107: 1931–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Engstrom G, Hedblad B, Janzon L. Reduced lung function predicts increased fatality in future cardiac events. A population‐based study. J Intern Med 2006; 260: 560–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Finkelstein J, Cha E, Scharf SM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2009; 4: 337–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Newman AB, Nieto FJ, Guidry U et al Relation of sleep‐disordered breathing to cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2001; 154: 50–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leone N, Courbon D, Thomas F et al Lung function impairment and metabolic syndrome: the critical role of abdominal obesity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 179: 509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gorter PM, van Lindert AS, de Vos AM et al Quantification of epicardial and peri‐coronary fat using cardiac computed tomography; reproducibility and relation with obesity and metabolic syndrome in patients suspected of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2008; 197: 896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hadamitzky M, Achenbach S, Al‐Mallah M et al Optimized prognostic score for coronary computed tomographic angiography: results from the CONFIRM registry (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: an InteRnational Multicenter Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: 468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Motoyama S, Sarai M, Harigaya H et al Computed tomographic angiography characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques subsequently resulting in acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54: 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Prahl U, Holdfeldt P, Bergstrom G, Fagerberg B, Hulthe J, Gustavsson T. Percentage white: a new feature for ultrasound classification of plaque echogenicity in carotid artery atherosclerosis. Ultrasound Med Biol 2010; 36: 218–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van den Bouwhuijsen QJ, Vernooij MW, Hofman A, Krestin GP, van der Lugt A, Witteman JC. Determinants of magnetic resonance imaging detected carotid plaque components: the Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Coxson HO, Dirksen A, Edwards LD et al The presence and progression of emphysema in COPD as determined by CT scanning and biomarker expression: a prospective analysis from the ECLIPSE study. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Christensen SE, Moller E, Bonn SE et al Two new meal‐ and web‐based interactive food frequency questionnaires: validation of energy and macronutrient intake. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. WHO . Definition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate hyperglycaemia, 2006.

- 37. WHO . Waist circumference and waist–hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation, 2008.

- 38. Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P et al Measurement and interpretation of the ankle‐brachial index: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012; 126: 2890–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM et al International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population‐based prevalence study. Lancet 2007; 370: 741–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G et al Standardisation of the single‐breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 720–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ostling G, Persson M, Hedblad B, Goncalves I. Comparison of grey scale median (GSM) measurement in ultrasound images of human carotid plaques using two different softwares. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2013; 33: 431–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Millon A, Mathevet JL, Boussel L et al High‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging of carotid atherosclerosis identifies vulnerable carotid plaques. J Vasc Surg 2013; 57: 1046–51 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McCollough CH, Ulzheimer S, Halliburton SS, Shanneik K, White RD, Kalender WA. Coronary artery calcium: a multi‐institutional, multimanufacturer international standard for quantification at cardiac CT. Radiology 2007; 243: 527–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Otsuka K, Fukuda S, Tanaka A et al Prognosis of vulnerable plaque on computed tomographic coronary angiography with normal myocardial perfusion image. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014; 15: 332–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ovrehus KA, Marwan M, Botker HE, Achenbach S, Norgaard BL. Reproducibility of coronary plaque detection and characterization using low radiation dose coronary computed tomographic angiography in patients with intermediate likelihood of coronary artery disease (ReSCAN study). Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012; 28: 889–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Joe E, Kim SH, Lee KB et al Feasibility and accuracy of dual‐source dual‐energy CT for noninvasive determination of hepatic iron accumulation. Radiology 2012; 262: 126–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hatano S. Experience from a multicentre stroke register: a preliminary report. Bull World Health Organ 1976; 54: 541–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A et al External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jernberg T, Attebring MF, Hambraeus K et al The Swedish Web‐system for enhancement and development of evidence‐based care in heart disease evaluated according to recommended therapies (SWEDEHEART). Heart 2010; 96: 1617–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Asplund K, Hulter Asberg K, Norrving B et al Riks‐stroke ‐ a Swedish national quality register for stroke care. Cerebrovasc Dis 2003; 15(Suppl 1): 5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Troeng T, Malmstedt J, Bjorck M. External validation of the Swedvasc registry: a first‐time individual cross‐matching with the unique personal identity number. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008; 36: 705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rao QA, Newhouse JH. Risk of nephropathy after intravenous administration of contrast material: a critical literature analysis. Radiology 2006; 239: 392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Goergen SK, Rumbold G, Compton G, Harris C. Systematic review of current guidelines, and their evidence base, on risk of lactic acidosis after administration of contrast medium for patients receiving metformin. Radiology 2010; 254: 261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Becker J, Babb J, Serrano M. Glomerular filtration rate in evaluation of the effect of iodinated contrast media on renal function. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 200: 822–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Carter RE et al Intravenous contrast material exposure is not an independent risk factor for dialysis or mortality. Radiology 2014; 273: 714–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Viberg J, Hansson MG, Langenskiold S, Segerdahl P. Incidental findings: the time is not yet ripe for a policy for biobanks. Eur J Hum Genet 2013; 22: 437–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Horeweg N, van der Aalst CM, Thunnissen E et al Characteristics of lung cancers detected by computer tomography screening in the randomized NELSON trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187: 848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harrison M, Rigby D, Vass C, Flynn T, Louviere J, Payne K. Risk as an attribute in discrete choice experiments: a systematic review of the literature. Patient 2014; 7: 151–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP et al Estimation of ten‐year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J 2003; 24: 987–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ridker PM, Paynter NP, Rifai N, Gaziano JM, Cook NR. C‐reactive protein and parental history improve global cardiovascular risk prediction: the Reynolds Risk Score for men. Circulation 2008; 118: 2243–51, 4p following 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ et al General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008; 117: 743–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Bennett G et al 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129: S49–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hippisley‐Cox J, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y et al Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ 2008; 336: 1475–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE Jr. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1951; 41: 279–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Boysen G, Nyboe J, Appleyard M et al Stroke incidence and risk factors for stroke in Copenhagen, Denmark. Stroke 1988; 19: 1345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hofman A, Darwish Murad S, van Duijn CM. The Rotterdam Study: 2014 objectives and design update. Eur J Epidemiol 2013; 28: 889–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G et al Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility‐Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 165: 1076–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Assmann G, Cullen P, Schulte H. Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10‐year follow‐up of the prospective cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study. Circulation 2002; 105: 310–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Vartiainen E, Laatikainen T, Peltonen M et al Thirty‐five‐year trends in cardiovascular risk factors in Finland. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39: 504–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Danesh J, Saracci R, Berglund G et al EPIC‐Heart: the cardiovascular component of a prospective study of nutritional, lifestyle and biological factors in 520,000 middle‐aged participants from 10 European countries. Eur J Epidemiol 2007; 22: 129–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR et al Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD 2010; 7: 32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. The ARIC investigators . The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol 1989; 129: 687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Stolk RP, Rosmalen JG, Postma DS et al Universal risk factors for multifactorial diseases: LifeLines: a three‐generation population‐based study. Eur J Epidemiol 2008; 23: 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Collins R. Protocol for a Large‐scale Prospective Epidemiological Resource ‐ The UK biobank. http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/scientists-3/. 2014.

- 75. Lind L, Elmstahl S, Bergman E et al EpiHealth: a large population‐based cohort study for investigation of gene‐lifestyle interactions in the pathogenesis of common diseases. Eur J Epidemiol 2013; 28: 189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL et al Multi‐ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156: 871–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL et al The Dallas Heart Study: a population‐based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. Am J Cardiol 2004; 93: 1473–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Falk E, Sillesen H, Muntendam P, Fuster V. The high‐risk plaque initiative: primary prevention of atherothrombotic events in the asymptomatic population. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2011; 13: 359–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Folsom AR, Kronmal RA, Detrano RC et al Coronary artery calcification compared with carotid intima‐media thickness in the prediction of cardiovascular disease incidence: the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 1333–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Elias‐Smale SE, Proenca RV, Koller MT et al Coronary calcium score improves classification of coronary heart disease risk in the elderly: the Rotterdam study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 1407–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Polonsky TS, McClelland RL, Jorgensen NW et al Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. JAMA 2010; 303: 1610–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Erbel R, Mohlenkamp S, Moebus S et al Coronary risk stratification, discrimination, and reclassification improvement based on quantification of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 1397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hendel RC, Patel MR, Kramer CM et al ACCF/ACR/SCCT/SCMR/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SIR 2006 appropriateness criteria for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group, American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Interventional Radiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48: 1475–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H et al European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1635–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Waugh N, Black C, Walker S, McIntyre L, Cummins E, Hillis G. The effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of computed tomography screening for coronary artery disease: systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2006; 10: iii–iv, ix‐x, 1‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ostrom MP, Gopal A, Ahmadi N et al Mortality incidence and the severity of coronary atherosclerosis assessed by computed tomography angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52: 1335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Min JK, Shaw LJ, Devereux RB et al Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all‐cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 1161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Graham MM, Faris PD, Ghali WA et al Validation of three myocardial jeopardy scores in a population‐based cardiac catheterization cohort. Am Heart J 2001; 142: 254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mark DB, Nelson CL, Califf RM et al Continuing evolution of therapy for coronary artery disease. Initial results from the era of coronary angioplasty. Circulation 1994; 89: 2015–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tanaka A, Shimada K, Yoshida K et al Non‐invasive assessment of plaque rupture by 64‐slice multidetector computed tomography–comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Circ J 2008; 72: 1276–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. What can mendelian randomisation tell us about modifiable behavioural and environmental exposures? BMJ 2005; 330: 1076–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho‐Melander M et al Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet 2012; 380: 572–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Rothman KJ, Gallacher JE, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol 2013; 42: 1012–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rosengren A, Eriksson H, Hansson PO et al Obesity and trends in cardiovascular risk factors over 40 years in Swedish men aged 50. J Intern Med 2009; 266: 268–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Number of aliquots proposed for delivery to the national biobank resource.

Table S2. Sequences used for magnetic resonance imaging.

Table S3. Details of settings and protocols used for computed tomography in SCAPIS.

Table S4. Epidemiological registers that will be used in SCAPIS.

Table S5. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in women and men free from cardiovascular disease at the baseline examination in the SCAPIS pilot trial.

Table S6. Risk of cardiovascular events in the next 10 years in the SCAPIS pilot trial estimated using four independent risk calculators with risk factors from Table S5.

Table S7. Incidence rate of coronary and stroke events in the Malmö Diet and Cancer study 8.

Table S8. Incidence rate of coronary and stroke events in a registry‐based cohort of men and women living in the city of Gothenburg.

Table S9. The predicted number of accumulated events at 2, 5 and 10 years after study completion.

Figure S1. The algorithm used in SCAPIS to identify subjects for whom administration of contrast medium could pose a risk. eGFR, glomerular filtration rate estimated from the serum creatinine level.

Figure S2. Mortality from ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke in Sweden as a function of age (data from the National Board of Health and Welfare).