Abstract

The Na+-coupled betaine symporter BetP shares a highly conserved fold with other sequence unrelated secondary transporters, e.g., with neurotransmitter symporters. Recently, we obtained atomic structures of BetP in distinct conformational states, which elucidated parts of its alternating access mechanism. Here, we report for the first time a structure of BetP in a new outward-open state in complex with an anomalous scattering substrate, adding a fundamental piece to an unprecedented set of structural snapshots for a secondary transporter. In combination with molecular dynamics simulations these structural data highlight important features of the sequential formation of the substrate and sodium-binding sites, in which coordinating water molecules play a crucial role. We observe a strictly interdependent binding of betaine and sodium ions during the coupling process. All three sites undergo progressive reshaping and dehydration during the alternating-access cycle, with the most optimal coordination of all substrates found in the closed state.

Introduction

BetP, an osmotic-stress regulated transporter from the betaine/choline/carnitine transporter family (BCCT) shares the conserved LeuT-like fold 1 of two inverted structural repeats of five transmembrane helices 2, 3, whose pseudo-symmetry has been proposed as mechanistic basis of the alternating-access mechanism of transport 4. Various transporters from diverse sequence families share this highly conserved fold 5, including other sodium-coupled transporters such as the hydantoin transporter Mhp1 6 and a galactose transporter vSGLT 7. Recently, several crystal structures of conformationally asymmetric BetP trimers have been reported 2, that almost completed our view of the alternating-access cycle for BetP. Nevertheless, some fundamental questions were left unanswered. In particular, a substrate-bound outward-open state of BetP was missing and therefore the molecular understanding of the key events of substrate and co-substrate binding, and the subsequent transition to the closed state, was unclear. Recent structural work on BetP identified a mutant (G153D) carrying an aspartate in the flexible stretch of transmembrane helix 1′ (TMH1′) 1, which is able to transport choline 8, exhibit an elevated apparent affinity for Na+ and preferably crystallizes in an outward-facing state 2. We have reported that crystallization of this mutant resulted in outward-facing open and outward-occluded apo states 2.

As most of the BetP structures exhibit only moderate resolution of ~3Å, at which an unambiguous assignment of substrates to the electron density is hampered, here we co-crystallize BetP-G153D in the presence of a choline analogue containing arsenic instead of nitrogen, with which the substrate can be traced by arsenic anomalous scattering. These types of organo-arsenic compounds are natural constituents of many organisms, particularly from marine environments 9. We show here that the slightly altered chemical nature of arseno-choline does not affect binding to BetP-G153D, although it leads to a reduction in Km compared to choline.

Co-crystallization of BetP-G153D and arseno-choline result in crystals in which BetP adopts the missing substrate-bound outward-facing state, with arseno-choline bound to the central binding site and revealing the binding mode of choline in detail. Subsequently, we use the new outward-facing substrate bound structure in molecular dynamics simulations to compare the detailed binding of substrate and sodium in outward-facing open (Ce), and outward-facing substrate bound (CeS) states to that in the closed state (CcS) 2, 10. The results indicate that the two sodium ion-binding sites undergo major re-arrangements that affect their degree of hydration. Thus, the new CeS state represents a missing puzzle piece in what is now an unprecedented set of structural snapshots for a secondary transporter, that together emphasize the role of both sodium ions in shaping and finally closing the central substrate binding site in accordance with the induced fit model.

Results

Binding and transport properties of arseno-choline

Titration of BetP-G153D reconstituted in proteoliposomes with arseno-choline in the presence of 100 mM NaCl (Fig. 1A) revealed a similar binding affinity to that of choline (Table 1). The arseno-choline binding isotherm reveals biphasic binding behavior and positive cooperativity (nHill = 1.69 ± 0.08), similar to the binding behavior of choline. Arsenic sustains two additional electron shells relative to nitrogen. Thus, the coordination of the trimethylarsonium group may differ slightly from that of trimethylammonium, which involves cation-π interactions with tryptophan residues in the substrate-binding site 2. However, that the substrate hydroxyl group appears to interact with the carboxylic side chain 8 of Asp153, which may suffice to compensate for any differences due to the As atom so that the binding affinity is comparable to that of choline. To demonstrate transport of arseno-choline, solid supported membrane (SSM)-based electrophysiology was performed with proteoliposomes of reconstituted 10 BetP-G153D. A transient current corresponding to transmembrane charge displacement was detected after activation with arseno-choline, showing that this compound can be transported (Fig. 1B). The peak maximum current plotted as a function of substrate concentration showed a 4-fold increase in Km for arseno-choline (Km = 523 ± 70 μM) compared to that of choline (Km = 135 ± 28 μM) (Fig. 1B and Table 1), suggesting some effect of the larger trimethylarsonium group on the transport kinetics of this substrate. Nevertheless, our thermodynamic and kinetic studies of arseno-choline indicate that the arseno-derivative can be considered a suitable substrate analogue. Therefore, we included this compound in co-crystallization trials, allowing us to trace binding to BetP-G153D using arsenic anomalous scattering.

Figure 1.

Binding and transport properties of arseno-choline. Closed squares (choline), open squares (arseno-choline). (A) Tryptophan fluorescence binding curve of choline and arseno-choline to BetP-G153D reconstituted in proteoliposomes. Each point shows the average for eight individual measurements. The error bars represent standard deviation (s.d.). (B) Normalized peak currents of sodium coupled transport of choline and arseno-choline to BetP-G153D. The graphs show average values from three individual recordings and the corresponding s.d.

Table 1.

Binding and transport kinetic parameters for choline and arseno-choline.

|

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kd | n | Km | |

|

| |||

| mM | Hill coefficient | μM | |

| Choline | 1.15 ± 0.09 | 1.38 ± 0.37* | 135 ± 28 |

| Arseno-choline | 1.30 ± 0.07 | 1.69 ± 0.08* | 523 ± 70 |

Hill coefficient determined on the basis of the first saturation event 41

An arseno-choline bound outward-open state (CeS)

Co-crystallization of BetP-G153D with arseno-choline yielded crystals diffracting to 2.95 Å resolution (Table S1). As observed previously for this mutant, the crystal structure reveals an asymmetric trimer 2, although unlike the earlier crystal structure, chain A and B adopt an arseno-choline bound outward-open conformation (CeS), and chain C an arseno-choline bound inward-open conformation (CiS) (Fig. 2A). The previous crystal structure of BetP-G153D contained substrate free outward-occluded (Ceoc) and outward-open states (Ce) 2. The appearance of the outward-facing state found exclusively in crystals of this mutant was attributed to the 6-fold higher apparent affinity for sodium, which presumably stabilizes this conformation by occupation of the Na2 site 11, 12. The new CeS state that we report here is also not frequently observed in the LeuT-like fold family. Indeed, only structures of the amino acid antiporter AdiC have been observed in a similar CeS state 13, while for LeuT only the competitive inhibitor-bound outward-open state 14 has been reported (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

Conformational states and arseno-choline binding observed in BetP-G153D. (A) Surface representation showing the periplasmic cavity. Chains A and B are in substrate bound outward-open state (CeS), while chain C is in substrate-bound inward-open conformation (CiS). (B) Central binding sites of chains A, B and C, respectively. Arseno-choline is shown in black, red and purple sticks. Anomalous difference Fourier maps are shown at 4.0σ, 7.0σ and 4.0σ levels for substrates in chain A, B and C, respectively.

In this study, we used an oversaturating concentration of arseno-choline (~8-fold above Kd ~ 1mM), which appears to preferentially populate the CeS state, presumably due to the distinct binding and transport characteristics of this substrate. Thus, the structures of protomers A and B, which we assign to the CeS state, contain a fully open central cavity that renders the central substrate and co-substrate binding sites sterically accessible from the periplasm, whereas a ~18 Å-thick protein density occludes these sites from the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). By contrast, in protomer C the central binding site is fully accessible to the cytoplasm, and is therefore assigned to the CiS state (Fig. 2A).

An anomalous difference Fourier map revealed prominent peaks in the central binding sites of chains A, B and C (Fig. 2B). These could be observed when using a contour level of up to 6.1σ for chain A, 11.8σ for chain B and 5.2σ for chain C. No additional arsenic anomalous peaks were observed at comparable contour levels besides the ones in the central binding sites, indicating that, at least in these conformations of G153D, other high affinity arseno-choline binding sites could not be discerned.

Similar to what was observed for the CcS state1, the binding site in the CeS state is formed by three tryptophan residues from TMH6′ arranged as in a prism (Trp-prism); Trp373, Trp374 and Trp377 coordinate the trimethylarsonium group of the substrate, while the carboxyl group of Asp153 and the backbone amide of Gly151 appear to hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl group of arseno-choline (Fig. 2B). During multiple 200ns-timescale molecular dynamics simulations of CeS monomers of BetP-G153D embedded in a hydrated bilayer of POPG lipids, these hydrogen bonds are readily formed, and the same overall coordination is maintained throughout (Fig. 3), providing confidence in the choice of arsenocholine as a substrate analog. A similar interaction between a side chain carboxyl group and the hydroxyl group of choline has been observed in other choline binding proteins, including: the substrate-binding protein ChoX of the ABC transporter ChoXWU from E. coli 15; the major autolysin (C-Lyta) from S. pneumonia 16; and the choline binding protein OpuBC from B. subtilis 17. This similarity indicates parallels in the binding modes of choline in membrane and soluble proteins.

Figure 3.

CeS state coordination of choline in the S1 binding site of BetP-G153D. (A) Typical coordination of choline (black sticks) during the MD simulations by TMH1′ and TMH6′ (cartoon helices). Key residues (sticks) and water molecules (ball-and-stick) are shown. Non-covalent interactions are shown as dashed lines. (B) Distances were measured between the N atom of choline and the center of mass of the side chains in the tryptophan box (W377, W374, and W377), or between the hydroxyl oxygen of choline and the N backbone atom of G151 or the closest carboxyl oxygen atom of D153. The distribution was calculated over three trajectories, each 200 ns long.

This position of the arseno-choline in the CeS conformations differs from that in the CiS state, where the trimethylarsonium group is displaced from the Trp-prism (Fig. 2B, right). The latter is similar to what was observed for choline as well as for betaine in the CiS state of a previously reported structure 8.

Analysis of the B-factors (Supplementary Fig. S2) and root mean squared fluctuations (RMSF, Supplementary Fig. S3) of the substrate binding site residues in the CeS state suggest that the unwound segment of TMH1′ and perhaps also residues Trp373 and Trp377 of TMH6′ that form the Trp-prism, increase their conformational rigidity upon substrate binding, as compared to the Ce state of BetP (Supplementary Fig. S2). Although such a comparison of B-factors should be considered with caution because the structures differ, a similar trend is observed on comparison of the related states for AdiC and LeuT (Supplementary Fig. S2) for the unwound segments of TMH1′ and for TMH6′, in which B-factors are reduced for the residues involved in substrate or competitive inhibitor binding, respectively 13, 14. Such entropic changes could conceivably facilitate the conformational changes between outward- and inward-facing states, imposing a dependence of the transition on substrate and co-substrate binding.

The Na2 sodium binding site in the CeS state

NaCl titration of BetP-G153D reconstituted in proteoliposomes revealed positive cooperativity (nHill = 1.9 ± 0.2) 2, similar to that observed for WT BetP 2. This cooperativity suggests that the mutant retains the two-Na+ binding stoichiometry of WT BetP 10. Recently, two sodium-binding sites in BetP were localized and functionally validated based on a crystal structure of the CcS state, symmetry considerations and molecular simulations 10. The Na2 site is highly conserved among symporters of the LeuT-like superfamily 18, and a positive peak in the Fo−Fc electron-density map was observed at this site in the earlier BetP CcS structure 2. We detected an equivalent peak in the Fo−Fc electron-density map at the Na2 site in the new CeS state structures (Fig. 4A), suggesting that sodium is bound to the Na2 site in the substrate-bound outward-open (CeS) conformation. This proposal is supported by the fact that a Na+ was stably coordinated at this Na2 site during multiple 200ns-long molecular dynamics simulations of the BetP-G153D CeS state (Fig. 4B–E).

Figure 4.

The Na2 binding site in outward-open states of BetP-G153D. (A) The CeS state structure (protomer B) in side view with Na2 and adjacent central substrate binding site in stick representation, coordinating Na+ (violet sphere) and arseno-choline (black, red and purple sticks), respectively. The inset shows the coordination of a Na+ ion (violet sphere) in the Na2 site. The Fo−Fc electron density map is shown in green at a level of 3.0σ. (B–E) The Na2 site in simulations of the substrate-bound CeS (B–C) and substrate-free Ce (D–E) states: (B, D) Example configurations in simulations of the CeS state (B) and the Ce state (D). Proteins and ions are presented as in (A), waters are shown as balls-and-sticks and water densities are shown as green surfaces. (C, E) Distance between Na+ ion and Na2-site oxygen atoms during three molecular dynamics simulations of the substrate bound CeS state (C), each 200ns long, and the substrate-free Ce state (E), each 100ns-long. (F) Betaine uptake rates in nmol·min−1·mg−1 cell dry weight (cdw) were measured as a function of the external sodium concentration in E. coli MKH13 cells expressing BetP WT or the mutant N309A. Each point shows the average of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent s.d.

We note that the Na2 site coordination in this outward-open state differs slightly from that in structures of the closed CcS state 2. For example, there are occasional fluctuations in the coordination by the F464 backbone carbonyl of CeS (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, the coordination of the Na2 site involves Asn309 from the gating helix TMH5′ (Fig. 4C–D). Asn309 is at the equivalent position of the key cation-substituting group Arg262 in a sodium-independent antiporter, CaiT 19, and is one turn above the position equivalent to Asp189 in vSGLT, which is thought to interact with the Na2 ion in that transporter 20, 21. We tested the importance of this residue for BetP by replacing Asn309 with alanine. Uptake assays in Escherichia coli MKH13 cells reveal that this substitution increases the apparent Km of BetP for sodium ~20-fold (Fig. 4F and Table 2) compared to that of BetP WT, confirming the predicted role of Asn309 in the sodium-dependence of substrate transport, and suggesting that the interaction observed in the CeS simulations is physiologically important.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for apparent sodium affinity measured from betaine uptake of WT BetP and N309A mutant.

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Km | Vmax | |

|

| ||

| μM | (nmol·min−1 · mg−1 cdw) | |

| WT | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 82.9 ± 4.8 |

| N309A | 79.7 ± 16.4 | 123.0 ± 9.7 |

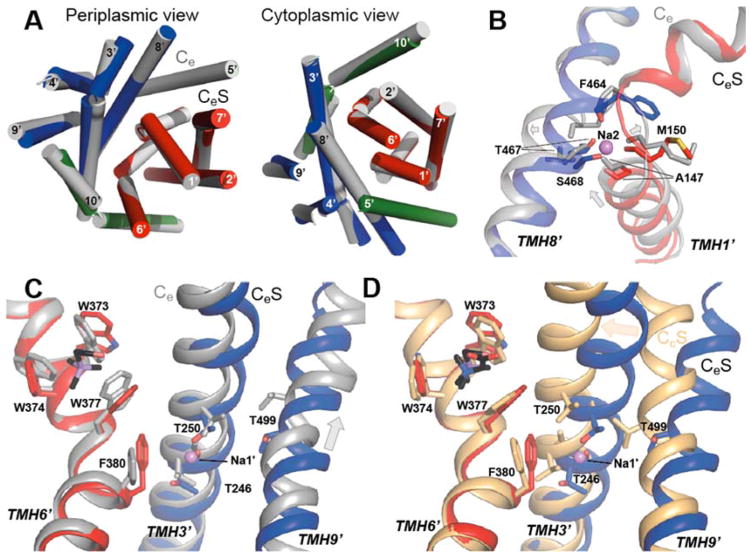

Unlike the aforementioned CeS- and CcS-state structures of BetP, no positive peak was detected at the Na2 site in the substrate-free outward-facing state 2 (Ce). This lack of a positive peak is consistent with the observed distortion of the binding site in the Ce structure (Table 3) due to a number of subtle changes in the structure. These changes are: a ~2 Å displacement and unwinding of the middle of TMH8′ near Phe464; a ~2 Å vertical translation of the cytoplasmic half of TMH3′ towards the site; as well as a shift in the unwound segment of TMH3′ away from the site. As a result, Thr467 and Met150 appear no longer close enough to coordinate the ion in the Ce state compared to the CeS state (Fig. 5A–B). Indeed, during simulations of Ce structures, an ion in the Na2 region was unable to interact with all ligands simultaneously, and mainly interacted with Ala147, Phe464 and Ser468 (Fig. 4D–E). Nevertheless, the ion did not escape from the Ce Na2 site during these simulations, unlike ions placed in the Na2 site of inward-facing (Ci) states of other transporters such as vSGLT 22 and Mhp1 6, where all contributing oxygen atoms are >2 Å further apart than in the Ce state (Table 3), so that the site is effectively abolished. Instead, in simulations of Ce, the Na+ ion maintained coordination by one or other backbone oxygen of TMH3′ (Fig. 4D), as well as an average of 2.0 ± 0.8 water molecules within 3 Å of the ion (Fig. 3E). The high degree of hydration of the Ce-Na2 site is consistent with the lack of a clear peak. This behavior is distinct from ions at Na2 in the inward CiS or closed CcS states, where the site is fully disrupted (and solvent-accessible) or fully formed (and completely inaccessible), respectively10 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Na+ binding site integrity in different states of BetP measured as the distance between coordinating groups in X-ray crystallographic structures and during molecular dynamics simulations thereof.

| State | System | d(Na1′) | Δd(Na1′) | d(Na2) | Δd(Na2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CcS | 4AIN-B | 4.7 | n.a. | 3.8 | n.a. |

| MD* | 4.7±0.3 | 0.0 | 3.5±0.2 | −0.3 | |

| Cc | 4AIN-A | 4.8 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 1.2 |

|

| |||||

| CeS | 4LLH-A | 4.9 | 0.2 | 4.7 | 0.9 |

| 4LLH-B | 4.7 | 0.0 | 3.7 | −0.1 | |

| MD | 5.8±0.5 | 1.1 | 4.0±0.5 | 0.2 | |

|

| |||||

| Ce | 4DOJ-B | 6.7 | 2.0 | 5.9 | 2.1 |

| MD | 5.8±0.4 | 1.1 | 6.1±1.4 | 2.3 | |

|

| |||||

| CiS | 4DOJ-C | 8.0 | 3.3 | 7.7 | 3.9 |

| 4LHH-C | 8.0 | 3.3 | 7.5 | 3.7 | |

| 3PO3-C | 8.3 | 3.6 | 7.4 | 3.6 | |

|

| |||||

| Ci | 3PO3-A | 8.9 | 3.6 | 6.9 | 3.1 |

| 3PO3-B | 6.8 | 2.1 | 7.3 | 3.5 | |

Systems are either crystal structures, listed as PDB and chain identifier, or mean ± standard deviation computed over three 100-ns molecular dynamics simulations of those structures, where available.

Simulations of CcS state described previously 10. Ion binding sites are defined as follows: for Na1, the distance (in Å) between T250 side-chain oxygen (TMH3′) and the center of the F380 (TMH5′) phenyl ring; for Na2, the distance between the carbonyl oxygen atoms of M150 (TMH1′) and F464 (TMH8′). The difference in binding site distances (Δd) is calculated relative to the value for the CcS state in 4AIN-B.

n.a., not applicable.

Figure 5.

Comparison of structures and ion binding sites in CeS (colors), Ce (grey) and CcS (tan) states of BetP and BetP-G153D. Sodium ions (violet spheres), and substrate (black sticks) are shown. Changes from the CeS state to the compared state are indicated using arrows. (A–C) Comparisons of substrate-free Ce (PDB entry 4DOJ chain B, grey) and substrate-bound CeS states (colors), showing the effect of substrate binding on the outward-open states on: (A) the overall structure, with helices shown as cylinders; (B) the Na2 binding site, showing protein (ribbons), binding site residues (sticks) and Na2 ion from the CeS structure (sphere). (C) the substrate site (S1) and Na1′ site, with protein shown as ribbons, and with substrate (black) and binding site residues as sticks. The location of the Na1′ ion is taken from the CeS simulations. (D) Comparison of Na1′ and substrate (S1) binding site regions in the substrate-bound outward-open (CeS, colors) and the substrate-bound closed (CcS; PDB entry 4AIN chain B, tan) states. The Na1′ ion location is taken from the CeS simulations.

In summary, these results suggest that the coordination of the Na2 site becomes progressively optimized as the protein transitions from the Ce through the CeS to the CcS states, where it adopts the most optimal coordination.

The Na1′ sodium binding site in the CeS and Ce states

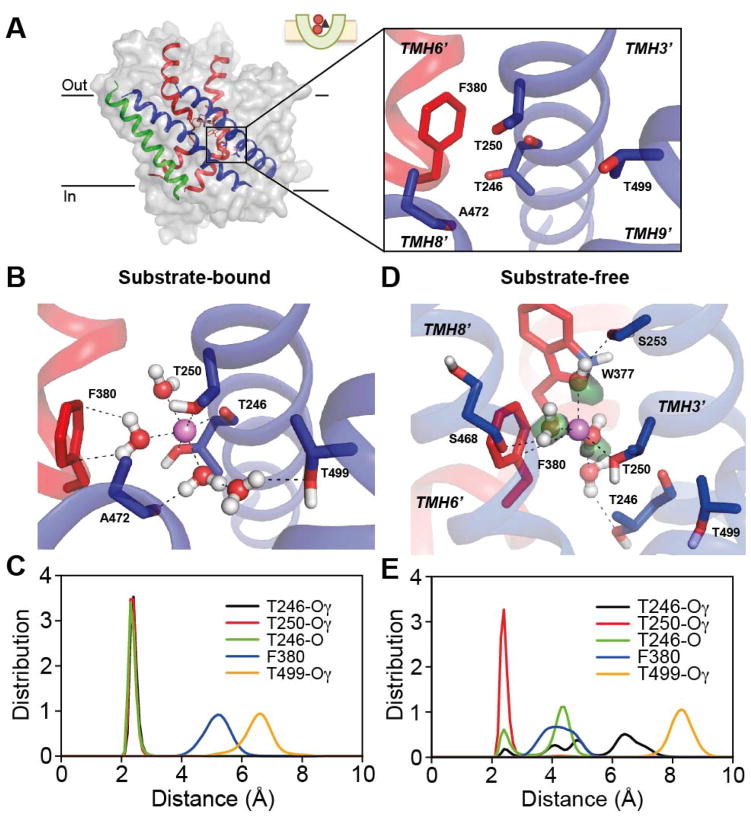

The position of the second sodium-binding site was recently proposed based on the structural symmetry between repeats 10, and the proposal for this so-called Na1′ site (which is distinct from the Na1 site in LeuT) was validated using biophysical assays and molecular simulations10. That study indicated a sodium ion at this position in the CcS state would be coordinated by the hydroxyl groups of Thr246 and Thr250 from TMH3′, by a water molecule that hydrogen bonds to Thr499 from TMH9′, and potentially by a cation-π interaction to the aromatic ring of Phe380 from TMH6′. Although no positive peak for a Na1′ sodium ion was observed in the Fo−Fc electron-density map of the outward-facing CeS state (Fig. 6A), molecular simulations of this CeS state indicated that an ion at the Na1′ site interacts with the two Thr residues in TMH3′ (Fig. 6B) in the same manner as in the closed CcS state 10, albeit with the ion further from the Phe380 ring (5.1 ± 0.5 Å on average in the CeS state) than in the closed CcS state 10 (4.6 ± 0.3 Å). Water molecules became inserted between Phe380 and the ion in the simulations of the CeS state (Fig. 6B) because the extracellular halves of TMH3′ and TMH6′ are further apart (Fig. 5D) than in the closed CcS state (Table 3). These water molecules exchanged readily with bulk waters through the extracellular pathway (Fig. 7). Specifically, ~70 different water molecules came within 3 Å of the Na1′ ion in the outward-facing CeS state and remained for at least 50 ps. Nevertheless, the ion remained coordinated to Thr246 and Thr250 in these simulations (Fig. 6C), apparently stabilized by a network of hydrogen bonds formed by, on average, 2.2 ± 0.4 water molecules residing within 3 Å of the Na1′ ion.

Figure 6.

The Na1′ binding site in outward-open states of BetP-G153D. (A) The CeS state structure (protomer B) in side view with Na1′ site and adjacent central substrate binding site in stick representation, coordinating arseno-choline (black, red and purple sticks). The inset shows residues that form the Na1′ site as reported for the closed substrate-bound CcS state. (B–E) The Na1′ site in simulations of the substrate-bound CeS (B–C) and substrate-free Ce (DE) states: (B, D) Example configurations in simulations of the substrate-bound CeS state (B) and the substrate-free Ce state (D). Proteins and ions are presented as in Fig. 6. (C, E) Distances between the Na+ ion and protein binding site atoms (either oxygen, or the center of the phenyl ring in F380) during simulations of the substrate bound CeS state (C) and the substrate-free Ce state (E).

Figure 7.

Comparison of ion binding site accessibility and coordination in the substrate-free Ce (A) and substrate-bound CeS (B) states of BetP-G153D observed using molecular dynamics simulations. The green surface indicates the density of water molecules occupying the extracellular pathway (defined as waters within 16 Å of D153) during three 200 ns trajectories. Protein snapshots were taken at 81 and 83 ns of the trajectories of the Ce and CeS states respectively. BetP protein is shown as a cut-away surface. Sodium ions are shown as violet spheres. Oxygen atoms of water and protein that form the Na2 and Na1′ binding site in the closed CcS state are shown as red spheres. Oxygen atoms in addition to those from the closed state structure coordinating the ion during molecular simulations of the corresponding state are shown as yellow spheres. Selected helices are shown as cartoons: TMH1′ and its symmetry equivalent TMH6′ (red), and TMH3′ and its symmetry equivalent TMH8′ (blue), with substrate choline shown as sticks.

We also compared the Na1′ site in the CeS state (Fig. 6A–C) with that in the Ce state (Fig. 6D–E), and found a similar situation to that described above for the Na2 site. That is, the sodium ion lacked a typical coordination shell in the Ce state, and yet remained coordinated to one or more of the same ligands (the side chain hydroxyl of Thr250 in this case), with all other ligands then substituted by water molecules (Fig. 6D) that were exchanging with the extracellular solution (Fig. 7). These arrangements were formed within 40 ns in three different simulations of the Ce state, after initially placing the ion centrally between the binding residues. The altered arrangement of the Ce state appears to be attributable to a ~3Å vertical translocation of TMH9′ relative to TMH3′ (Fig. 5C), which separates Thr499 from the other residues in the site (Fig. 5C and 6D), preventing formation of a stable water bridge that includes two water molecules in the CeS state (Fig. 6B) or a single water in the CcS state10.

In spite of the tenuous and minimal number of direct interactions with the protein, the sodium ion at Na1′ in the Ce state formed a stable network of interactions with 3.4 ± 0.5 water molecules (Fig. 6D–E and Fig. 7). These water molecules in turn formed a network of hydrogen bonds with surrounding groups including, notably, the side chain amine of Trp377 from TMH6′ and the Ser253 hydroxyl from TMH3′, both of which shape the substrate binding site 2. The hydrogen bond network also occasionally included the backbone carbonyl of Ala469 or the hydroxyl of Ser468 from TMH8′, which forms the Na2 site (Fig. 6D).

We reiterate that no positive peak in the Fo−Fc electron-density map at the Na1′ site was observed in the CeS state nor in any of the previously crystallized states of BetP 2, despite strong evidence that an ion binds to that region, as described above. This lack of a peak might plausibly be a consequence of the dynamic nature of such a well-hydrated ion binding site, or potentially also of a reduction in occupancy at the Na1′ site in crystals upon dehydration.

Discussion

To date, structures of BetP WT and the choline-transporting mutant BetP-G153D have provided eight distinct conformational states (Ceoc, CeNa, CeS, CcS, CiocS, CiS, Ci, Cc) (Fig. 8) 2, 8, 23, which after comparison to the crystallized outward- and inward-facing states of Mhp1 and LeuT, revealed similar mechanistic principles but also unique features in each individual system 2. The choline-transporting BetP-G153D exhibits a higher affinity for Na+ than WT protein. This mutant also tends to crystallize in the apo outward-occluded and outward-open states, while the WT crystallizes in either inward or closed states, depending on the concentration of co-crystallized substrate. Thus, we have now been able to observe substrate in all three main chain conformations, namely CeS, CcS and CiS. This wealth of BetP structures reveals distinct positions of the substrate during its transport trajectory through BetP. While it should be kept in mind that we are comparing structures that have been crystallized with different substrates, we note that the inward-facing CiS state has been observed with both betaine and choline, with nearly identical positions for both trimethyammonium compounds 2, and therefore the distinct positions observed for substrate in the different states are likely to be physiologically relevant.

Figure 8.

The eight conformations of BetP and BetP-G153D determined by X-ray crystallography to date (green): substrate-free outward-open bound to sodium (Ce2Na) (PDB entry 4DOJ); substrate-bound outward-open (CeS) (PDB entry 4LLH, reported here); substrate-bound closed (CcS) (PDB entry 4AIN); substrate-bound inward-occluded (CiocS) (PDB entry 2WIT); substrate-bound inward-open (CiS) (PDB entries 4DOJ/3P03/4AIN/4LLH); substrate-free inward-open (Ci) (PDB entry 4AMR); substrate-free closed (Cc) (PDB entry 4AIN); and substrate-free outward-occluded (Ceoc) (PDB entry 4DOJ).

The anomalous scattering demonstrated that arsenocholine is bound to the structure reported here, which allowed a comparison of substrate-free (Ce) and -bound (CeS) outward-open states. MD simulations suggest that sodium is bound, albeit loosely, to both the Na1′ and Na2 sites in both states (Figs. 4, 6), and therefore we reassign the Ce structure (monomer B of PDB entry 4DOJ) to a Ce2Na state (Fig. 8). The observation that an ion remains coordinated at a solvent-accessible Na2 site in the substrate-free Ce2Na state mirrors observations for an outward-open structure of another LeuT-fold transporter, Mhp1 6. In both transporters, binding of substrate and formation of the CeS state leads to occlusion of the Na2 site from the extracellular solution (Fig. 7) 6. Our simulations also suggest a concomitant increase in stability of the ion-protein interactions at the Na2 site in the CeS state compared to the Ce2Na state (Fig. 4). These changes reflect a number of small helix reorganizations around the site that improve the Na2 coordination in the CeS state (Fig. 5B), rendering it very similar to that in the CcS state (Table 3) 10.

In the case of the Na1′ site, by contrast, the ion is accessible to water in both the Ce2Na and CeS states (Fig. 7). However, similar to Na2, the Na1′ site exhibits significantly fewer stable protein-ion interactions in the Ce2Na state compared to the substrate-bound form (CeS, Fig. 6) or the closed CcS state 10, due to the shift in TMH9′ (Fig. 5C). Complete closure of the periplasmic pathway in the transition between the two holo forms (CeS to CcS) involves further contraction of TMH3′ and TMH9′ towards TMH8′ (Fig. 5D), which brings the ion ~0.5 Å closer to F380 (Fig. 6 cf. 10).

Meta-stable ion binding sites, such as those seen here for the Ce2Na state, that are proximal to, and involve a number of ligands from, the main binding sites, may be useful because they enhance the local ion concentration. Indeed, solvated, meta-stable sites appear to be a common theme for ion-coupled transporters, and been identified during MD simulations and free energy calculations of vSGLT 20, 21 and Mhp1 24, as well as LeuT 25. The important role of individual water molecules binding sodium within transporter proteins is underlined by the ion-water coordination observed in a recent structure of Drosophila melanogaster dopamine transporter (dDAT) 26, as well as in c-subunits of ATP-synthase rotor rings 27.

Together, these results suggest a sequential Na+/substrate binding process in which ions are loosely associated with partially-formed, partially-hydrated Na1′ and Na2 sites in the outward-open state, in the absence of substrate. Studies of other LeuT homologs indicate distinct roles for the two cations in transport 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 and, in terms of binding order, the most likely scenario appears to be that Na2 would bind before Na1 28. Indeed, spectroscopic and computational evidence that sodium shifts the equilibrium of LeuT towards opening of the central binding site to the periplasm 11, 12, 24; this, combined with the fact that the Na2 site is conserved among sodium-coupled transporters, suggests that Na2 is required for the conformational change. A similar mechanism may be adopted by BetP, since the Na2 site residues are closer together in the outward-open states than in the inward-open states (Table 3).

The finding that both ions bind to the empty transporter before substrate is consistent with electrophysiological studies of human Na+-coupled glucose symporter (hSGLT1), a homolog of vSGLT 30. In the case of BetP and Mhp1, one effect of substrate binding is to occlude the Na2 site, which should reduce the probability of ion unbinding 6, 24. Complete closure to form the CcS state then involves optimization of the binding interactions, at which point the energy gained by binding is maximal. By analogy with enzymatic mechanisms, this closed state is therefore a transition state, in line with the induced transition fit model proposed by Klingenberg 33. However, further analysis of BetP will be required to further validate this hypothesis. For example, in future work it would be of interest to follow the approach of Loo et al 30, and to compute the potential of mean force of the ions along their pathway into the binding sites in BetP to predict whether there is a significant barrier to formation of these assumed states.

In conclusion, results from a combination of structural studies and molecular simulations reveal for the first time for a secondary transporter how binding of coupling ions may involve progressive dehydration and concurrent coordination by protein residues. Studies of subsequent steps in the cycle will be required to address the question of whether the binding steps alone, or other later events, determine the strict ion-substrate coupling in BetP.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of arseno-choline

Arseno-choline was obtained 34 by heating trimethylarsine with bromo-ethanol, followed by re-crystallisation from methanol/acetone; the purity (>99.5 %) of the compounds was established by NMR spectroscopy and HPLC/mass spectrometry (inductively coupled plasma MS and electrospray MS).

Cell culturing and protein purification

Cell culture and protein preparation methods have been described previously23. E. coli DH5αmcr35 were used for the heterologous expression of strep-betP. Cells were grown at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with carbenicillin (50 μg/ml) and induction was initiated with anhydrotetracycline (200 μg/l). Cells were harvested at 4 °C by centrifugation and resuspended in buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) and protease inhibitor Pefabloc 0.24mg/ml. Membranes were isolated from disrupted cells and solubilized with 1% β-dodecyl-maltoside (DDM) when purified protein was subsequently crystallized or reconstituted. The protein was then loaded on a StrepII-Tactin macroprep® column, washed with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 8.6 % Glycerol, 0.1 % DDM, and eluted with 5 mM desthiobiotin, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 8.7% glycerol and 0.6% Cymal-5, if used for crystallization, or 0.1 % DDM if used for reconstitution. Prior to crystallization the protein was loaded onto a Superose 6 (GE Healthcare) size-exclusion column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl and 0.6 % Cymal-5. This purified protein was concentrated at 4 °C to approx. 10 mg/ml at 3000 g in a Vivaspin tube (Vivascience) with a 100k -molecular-weight cut-off, and incubated for 16 hours at 4 °C with either 8 mM arseno-choline or 1 mM arseno-betaine.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis of the pASK-IBA5betP20 and pASK IBA7betPΔN29/E44E45E46/AAA23 plasmids were performed using QuickChangeTM kit (Stratagene), Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase, and specific Oligonucleotides. The mutations were verified by nucleotide sequencing. The fully functional mutant BetP(ΔN29/E44E45E46/AAA/G153D) was used for crystallization purposes yielding in improved diffraction power and isotropy of the crystals.

Crystallization and structure determination

BetP-ΔN29/E44E45E46/AAA/G153D was co-crystallized with 8 mM arseno-choline at 18 °C by vapour diffusion in hanging drops of 1 μl protein solution with 1 μl of 100 mM Na-tri-citrate (pH 5.3–5.6), 300 mM NaCl or RbCl, 17–24% PEG 400 as reservoir solution. Crystals of BetP-ΔN29/EEE44/45/46AAA/G153D diffracted to 2.9 Å and data were collected on the beamline PXII at the Swiss Light Source (Swiss Light Source at the Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen - Switzerland). Data were collected at the K edge for arsenic, using a wavelength of ~1.043 Å. Data were processed using the XDS package36 and the anisotropy was corrected on the UCLA Diffraction Anisotropy Server (http://services.mbi.ucla.edu/anisoscale/)37. Structure was determined by molecular replacement with BetP (PDB entry 4DOJ) as search model using PHASER38 and refinement was performed using PHENIX39 combined with manual rebuilding in COOT40.

Protein reconstitution into liposomes

Functional reconstitution of BetP-G153 was performed as described41. Briefly, liposomes (20 mg phospholipid/ml) from E. coli polar lipids (Avanti polar lipids) were prepared by extrusion through polycarbonate filters (100 nm pore-size) and diluted 1:4 in buffer (250 mM KPi pH 7.5). After saturation with Triton X-100, the liposomes were mixed with purified protein at a lipid/protein ratio of 10:1 (w/w). BioBeads at ratios (w/w) of 5 (BioBeads/Triton X-100) and 10 (BioBeads/DDM) were added to remove detergent. Finally, the proteoliposomes were centrifuged and washed before being frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Tryptophan fluorescence-binding assay

Binding assays were performed with 100 μg/ml of purified BetP-G153D in proteoliposomes41. Choline and arseno-choline concentrations ranged from 0.1 to 16 mM for measurements at 100 mM NaCl and pH 7.5. Choline concentrations ranged from 0.8 to 30 mM at pH 5.5 and 0.8 to 100 mM at pH 7.5 in absence of NaCl. Tryptophan fluorescence emission between 315 and 370 nm was recorded on a Hitachi F-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer and averaged over eight readings, with the excitation wavelength set to 295 nm and a slit width of 2.5 or 5.0 nm for excitation or emission respectively. The mean value and standard deviation at the 340 nm emission maximum was plotted for each substrate concentration. Binding constants were derived by fitting with the program GraphPad Prism version 5.0c for Mac OS X, GraphPad Software42.

SSM-based Electrophysiology

Solid supported membrane-based electrophysiology was performed as described10, 43, 44 using 40 μL of proteoliposomes at a protein concentration of 1 mg/mL. Briefly, experiments were carried out at room temperature (22° C). The solution-exchange protocol consisted of four phases with a total duration 4.8s. (i) nonactivating solution (2.5 s), (ii) activating solution (0.8 s), (iii) nonactivating solution (0.5 s), (iv) resting solution (1.0 s). The resting solution was composed of 250 mM KPi buffer (7.5). Nonactivating and activating solution also contained 250 mM KPi buffer (pH 7.5). The osmolality of nonactivating and activating solution was kept constant. Activation by choline or arseno-choline was performed using a nonactivating solution with x μM glycine plus 500 mM NaCl and an activating solution with corresponding x μM choline or arsenocholine plus 500 mM NaCl. Thereby an osmolar gradient was established when switching from the resting to the non-activating solution at the start of the experiment. Note that during the final experiments (several minutes) the cuvette contained resting solution to ensure low osmolar conditions in the proteoliposomes. Transient currents were recorded at the concentration jumps taking place from nonactivating to activating buffers. The current amplifier was set to a gain of 109–1010 V/A, and low-pass filtering was a 300 – 1,000 Hz.

Transport Assays

Uptake of [14C]-betaine in E. coli cells was performed as described45. E. coli MKH13 cells expressing a particular strep-betP mutant were cultivated at 37 °C in LB medium containing carbenicillin (50 μg/mL) and induced at an OD600 of 0.5 by adding anhydrotetracycline (200 μg/L). After 2 h the cells were harvested and washed in buffer containing 25 mM KPi buffer (pH 7.5) and then were resuspended in the same buffer containing 20 mM glucose. For uptake measurements the external osmolality was adjusted with KCl at a constant value of 800 mOsmol/kg. Sodium titration was performed by adjusting the NaCl concentration in the buffer. Cells were incubated for 3 min at 37 °C before the addition of 250 μM [14C]-betaine. Betaine uptake was measured at various time intervals, after cell samples were passed through glass fiber filters (APFF02500; Millipore) and were washed twice with 2.5 mL of 0.6 M KPi buffer. The radioactivity retained on the filters was quantified by liquid scintillation counting.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were carried for monomers taken from two different crystallographic structures: 1) monomers A and B of the structure presented here (PDB 4LLH), which are both in outward-open substrate-bound (CeS) states; and 2) monomer B of PDB entry 4DOJ, which is in an outward-open apo (Ce) state. Protonation states were assigned according to calculations performed on the X-ray structures using MCCE2.046. Specifically, residues His188, His192, His445, His482 and His570 were protonated at their Nε atom while His176, His176, and His573 were protonated at their Nδ atoms. Based on the same calculations, Glu161 was assumed to be neutral, while Asp153 was charged. The likely location of buried water molecules was identified using DOWSER47.

The protein was inserted into a 50:50 diastereoisomeric mixture of 219 palmitoyl oleoyl phosphatidyl-glycerol (POPG) lipid molecules, hydrated with salt water. Specifically, monomers A and B of the CeS state were solvated by 15140 and 15149 water molecules, plus 245 and 254 sodium ions, respectively and the Ce structure was solvated by 15126 water molecules and 253 sodium ions. All three systems also contain 27 chloride ions to neutralize any net charge and to maintain an ~0.15 M salt concentration. The final systems were ~91 × 91 × 96 Å in size.

In the CeS structures, a substrate choline molecule and an ion at Na2 were placed according to positive peaks observed in the Fo−Fc difference density map, whereas the sodium at Na1′ was placed equidistant between the hydroxyl oxygen atoms of T246 and T250 and the center of the F380 phenyl ring. A water molecule was placed adjacent to the Na1′ so as to indirectly coordinate T499 10. In the Ce structure, sodium ions were placed based on superposition of the simulated CcS structure (monomer B of 4AIN).

The complete monomer-bilayer system was set up using GRIFFIN48. Briefly, GRIFFIN was first used to carve out lipid and water molecules from the equivalent volume of the protein. Subsequently, a three-step optimization was performed, with each step 50ps long and with external forces of 1.0, 2.0, then 3.0 kcal·mol−1·Å2 or 1.0, 1.5, then 2.0 kcal·mol−1·Å2 used for the Ce or CeS structures respectively. After 1,000 steps of conjugate gradients energy minimization, 20 ns of MD simulation was carried out in which all non-hydrogen atoms of the protein, ligand, and bound sodium ions were constrained to their initial positions using springs with progressively smaller force constants, starting at 15 kcal·mol−1·Å2. During the equilibration of the CeS state, distance constraints were applied between choline and the tryptophan box (W373, W374, and W377) as well as with D153, in order to maintain the substrate orientation and position as in the CeS X-ray structures. Similarly, the distances between sodium ions and their coordinating residues (T246, T250, and F380 for Na1 and A147, M150, F464, T467, and S468 for Na2) were constrained. Analysis was carried out every ps of unconstrained simulations, each 200 ns (for CeS) or 100ns (for Ce) in length.

All MD simulations were performed using NAMD49. Periodic boundary conditions were used. A real-space cutoff of 12 Å was used for both van der Waals and long-range electrostatics; the distance at which the switching function began to take effect was 10 Å. The time step was 2 fs. The SHAKE algorithm50 was used to fix all bond lengths. Constant temperature (310 K) was set with a Langevin thermostat51, with a coupling coefficient of 0.2 ps−1. A Nosé–Hoover Langevin barostat52 was used to apply constant pressure normal to the membrane plane, with an oscillation period of 200 fs and the damping time scale set to 50 fs. The surface area in the membrane plane was kept constant.

The all-atom CHARMM27 force field was used for protein53, 54 and ions55, and TIP3P was used for water molecules56. Force field parameters for POPG were kindly provided by H. Jang (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD)57. The parameters for choline were taken from the CHARMM general force field (CGenFF) topology and parameter files58.

The MD trajectories were analyzed with CHARMM and Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD)59.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Susanne Ressl for important insights on using arseno-compounds for co-crystallization, and Caroline Koshy and José Faraldo-Gómez for helpful discussions. We thank Klaus Fendler and Özkan Yildiz for their support with SSM and X-ray diffraction experiments. We also thank the staff of the Swiss Light Source (SLS, PXII) for their continuous support. This work was supported by the International Max Planck Research School (IMPRS), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB807 “Transport and communication across biological membranes”) and the Transport Across Membranes grant (TRAM).

Footnotes

The numbering of the BetP TM-helices was adapted to the LeuT numbering for better comparison. Therefore, TM1′–TM10′ correspond to TM3-TM12, while TM1 and TM2 are now assigned as TM(-2) and TM(-1), respectively.

Author Contributions

C.P. performed transport measurements, processing and refinements of crystallographic data; B.F. performed transport and binding measurements, collection and processing of data; A.M. performed molecular dynamics simulations; K.F. performed synthesis of arseno-compounds; B.F., A.M., L.F., C.Z. and C.P. analyzed the data; C.P., L.F. and C.Z. directed the research; and C.P., L.F., and C.Z. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Yamashita A, Singh SK, Kawate T, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 2005;437:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nature03978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez C, Koshy C, Yildiz O, Ziegler C. Alternating-access mechanism in conformationally asymmetric trimers of the betaine transporter BetP. Nature. 2012;490:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature11403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forrest LR, Kramer R, Ziegler C. The structural basis of secondary active transport mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:167–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forrest LR, et al. Mechanism for alternating access in neurotransmitter transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10338–10343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804659105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong FH, et al. The Amino Acid-Polyamine-Organocation Superfamily. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2012;22:105–113. doi: 10.1159/000338542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimamura T, et al. Molecular basis of alternating access membrane transport by the sodium-hydantoin transporter Mhp1. Science. 2010;328:470–473. doi: 10.1126/science.1186303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faham S, et al. The crystal structure of a sodium galactose transporter reveals mechanistic insights into Na+/sugar symport. Science. 2008;321:810–814. doi: 10.1126/science.1160406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez C, Koshy C, Ressl S, Nicklisch S, Kramer R, Ziegler C. Substrate specificity and ion coupling in the Na+/betaine symporter BetP. EMBO J. 2011;30:1221–1229. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francesconi KA. Current perspectives in arsenic environmental and biological research. Environmental Chemistry. 2005;2:141–145. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khafizov K, et al. Investigation of the sodium-binding sites in the sodium-coupled betaine transporter BetP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E3035–3044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209039109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y, Terry D, Shi L, Weinstein H, Blanchard SC, Javitch JA. Single-molecule dynamics of gating in a neurotransmitter transporter homologue. Nature. 2010;465:188–193. doi: 10.1038/nature09057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claxton DP, et al. Ion/substrate-dependent conformational dynamics of a bacterial homolog of neurotransmitter:sodium symporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:822–829. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kowalczyk L, et al. Molecular basis of substrate-induced permeation by an amino acid antiporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3935–3940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018081108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh SK, Yamashita A, Gouaux E. Antidepressant binding site in a bacterial homologue of neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 2007;448:952–956. doi: 10.1038/nature06038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oswald C, et al. Crystal structures of the choline/acetylcholine substrate-binding protein ChoX from Sinorhizobium meliloti in the liganded and unliganded-closed states. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32848–32859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez-Tornero C, Lopez R, Garcia E, Gimenez-Gallego G, Romero A. A novel solenoid fold in the cell wall anchoring domain of the pneumococcal virulence factor LytA. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:1020–1024. doi: 10.1038/nsb724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pittelkow M, Tschapek B, Smits SH, Schmitt L, Bremer E. The crystal structure of the substrate-binding protein OpuBC from Bacillus subtilis in complex with choline. J Mol Biol. 2011;411:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez C, Ziegler C. Mechanistic aspects of sodium-binding sites in LeuT-like fold symporters. Biol Chem. 2013;394:641–648. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalayil S, Schulze S, Kühlbrandt W. Arginine oscillation explains Na+ independence in the substrate/product antiporter CaiT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17296–17301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309071110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisha I, Laio A, Magistrato A, Giorgetti A, Sgrignani J. A Candidate Ion-Retaining State in the Inward-Facing Conformation of Sodium/Galactose Symporter: Clues from Atomistic Simulations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9:1240–1246. doi: 10.1021/ct3008233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Tajkhorshid E. Ion-releasing state of a secondary membrane transporter. Biophys J. 2009;97:L29–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe A, et al. The mechanism of sodium and substrate release from the binding pocket of vSGLT. Nature. 2010;468:988–991. doi: 10.1038/nature09580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ressl S, Terwisscha van Scheltinga AC, Vonrhein C, Ott V, Ziegler C. Molecular basis of transport and regulation in the Na(+)/betaine symporter BetP. Nature. 2009;458:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature07819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao C, Noskov SY. The molecular mechanism of ion-dependent gating in secondary transporters. PLoS Comp Biol. 2013;9:e1003296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao C, Stolzenberg S, Gracia L, Weinstein H, Noskov S, Shi L. Ion-Controlled Conformational Dynamics in the Outward-Open Transition from an Occluded State of LeuT. Biophys J. 2012;103:878–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penmatsa A, Wang KH, Gouaux E. X-ray structure of dopamine transporter elucidates antidepressant mechanism. Nature. 2013;503:85–90. doi: 10.1038/nature12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meier T, Krah A, Bond PJ, Pogoryelov D, Diederichs K, Faraldo-Gómez JD. Complete ion-coordination structure in the rotor ring of Na+-dependent F-ATP synthases. J Mol Biol. 2009;391:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meinild A-K, Forster IC. Using lithium to probe sequential cation interactions with GAT1. AJP: Cell Physiology. 2012;302:C1661–1675. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00446.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felts B, et al. The two Na+ sites in the human serotonin transporter play distinct roles in the ion coupling and electrogenicity of transport. J Biol Chem. 2013;289:1825–1840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.504654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loo DDF, Jiang X, Gorraitz E, Hirayama BA, Wright EM. Functional identification and characterization of sodium binding sites in Na symporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4557–E4566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319218110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noskov SY, Roux B. Control of ion selectivity in LeuT: Two Na+ binding sites with two different mechanisms. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2008;377:804–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Y, Zomot E, Kanner BI. Identification of a lithium interaction site in the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transporter GAT-1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22092–22099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klingenberg M. Ligand-protein interaction in biomembrane carriers. The induced transition fit of transport catalysis. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8563–8570. doi: 10.1021/bi050543r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irgolic KJ, Junk T, Kos C, McShane WS, Pappalardo GC. Preparation of trimethyl-2-hydroxyethylarsonium (arsenocholine) compounds. Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 1987;1:403–412. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant SG, Jessee J, Bloom FR, Hanahan D. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4645–4649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strong M, Sawaya MR, Wang S, Phillips M, Cascio D, Eisenberg D. Toward the structural genomics of complexes: crystal structure of a PE/PPE protein complex from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8060–8065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602606103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ge L, Perez C, Waclawska I, Ziegler C, Muller DJ. Locating an extracellular K+-dependent interaction site that modulates betaine-binding of the Na+-coupled betaine symporter BetP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E890–898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109597108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Motulsky H. Analyzing Data with GraphPad Prism. GraphPad Software Inc; San Diego CA: 1999. http://www.graphpad.com. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz P, Garcia-Celma JJ, Fendler K. SSM-based electrophysiology. Methods. 2008;46:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khafizov K, Perez C, Quick M, Fendler K, Ziegler C, Forrest L. Structural symmetry reveals the sodium binding sites in the betaine transporter BetP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209039109. under revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perez C, Khafizov K, Forrest LR, Kramer R, Ziegler C. The role of trimerization in the osmoregulated betaine transporter BetP. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:804–810. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexov EG, Gunner MR. Incorporating protein conformational flexibility into the calculation of pH-dependent protein properties. Biophys J. 1997;72:2075–2093. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78851-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, Hermans J. Hydrophilicity of cavities in proteins. Proteins. 1996;24:433–438. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199604)24:4<433::AID-PROT3>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staritzbichler R, Anselmi C, Forrest LR, Faraldo-Gomez JD. GRIFFIN: A Versatile Methodology for Optimization of Protein-Lipid Interfaces for Membrane Protein Simulations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2011;7:1167–1176. doi: 10.1021/ct100576m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips JC, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical-Integration of Cartesian Equations of Motion of a System with Constraints - Molecular-Dynamics of N-Alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adelman SA, Doll JD. Generalized Langevin Equation Approach for Atom-Solid-Surface Scattering - General Formulation for Classical Scattering Off Harmonic Solids. J Chem Phys. 1976;64:2375–2388. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feller SE, Zhang YH, Pastor RW, Brooks BR. Constant-Pressure Molecular-Dynamics Simulation - the Langevin Piston Method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mackerell AD, Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL., 3rd Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feller SE, Gawrisch K, MacKerell AD., Jr Polyunsaturated fatty acids in lipid bilayers: intrinsic and environmental contributions to their unique physical properties. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:318–326. doi: 10.1021/ja0118340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nina M, Beglov D, Roux B. Atomic radii for continuum electrostatics calculations based on molecular dynamics free energy simulations. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:5239–5248. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jang H, Ma B, Woolf TB, Nussinov R. Interaction of protegrin-1 with lipid bilayers: Membrane thinning effect. Biophys J. 2006;91:2848–2859. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vanommeslaeghe K, et al. CHARMM General Force Field: A Force Field for Drug-Like Molecules Compatible with the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Biological Force Fields. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:671–690. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph Model. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.