Abstract

Purpose of review

The paediatric HIV epidemic is changing. Over the past decade, new infections have substantially reduced whilst access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) has increased. Overall this success means that numbers of children living with HIV are climbing. In addition, the problems in adults of chronic inflammation resulting from persistent immune activation even following ART-mediated suppression of viral replication are magnified in children infected from birth.

Recent findings

Features of immune ontogeny favor low immune activation in early life, whilst specific aspects of paediatric HIV infection tend to increase it. A subset of ART-naïve non-progressing children exists in whom normal CD4 counts are maintained in the setting of persistent high viremia and yet in the context of low immune activation. This sooty mangabey-like phenotype contrasts with non-progressing adult infection characterized by the expression of protective HLA class I molecules and low viral load. The particular factors contributing to raised or lowered immune activation in paediatric infection, and that ultimately influence disease outcome, are discussed.

Summary

Novel strategies to circumvent the unwanted long-term consequences of HIV infection may be possible in children in whom natural immune ontogeny in early life militates against immune activation. Defining the mechanisms underlying low immune activation in natural HIV infection would have applications beyond paediatric HIV.

Keywords: paediatric HIV, immune activation, immune ontogeny

INTRODUCTION

Of the 37 million people living with HIV, 2.6 million are children (UNAIDS 2014). Despite optimized strategies of prevention-of-mother-to child transmission (PMTCT), an estimated 220,000 children became HIV infected in 2014, leaving HIV/AIDS still a major cause for infant and child death mainly in sub-Saharan countries (150,000 deaths per year) (UNAIDS 2014). Without treatment, vertically infected infants progress to disease more rapidly than adults, with a mortality exceeding 50% after 2 years (1-3). The differential rates of HIV disease progression in adults and children relate in part to the ontogeny of the immune response. Immunity in early infancy is characterized by a highly active innate immune system and the preferential induction of Th2 and Th17 cell responses. This immune strategy protects the child against extracellular bacterial pathogens rather than against intracellular bacterial pathogens and viruses (4, 5). CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, which are abundant at birth (6, 7), inhibit Th1 cell immunity and help maintain T cell tolerance. This Th2-directed bias in early life is likely to be an adaptation that has evolved to prevent harmful pro-inflammatory Th1 responses against maternal allo-antigens while in-utero (8) and the plethora of newly encountered environmental antigens after birth (3). However, this ‘approach’ compromises immunity to intracellular pathogens such as HIV (9).

Successful, disease-free co-existence with HIV, whether in adult or paediatric infection, appears to depend not so much on containment of viral replication, but on the persistent generalized immune activation that typically results from HIV infection. A small fraction of ART-naïve, HIV-infected adults achieve a state of ‘elite’ control of viral replication, in which viral load is maintained below the level of detection; and yet a proportion of even these ‘elite controllers’ develop AIDS as a result of high immune activation (10). The clearest example of the disconnect between the level of viral replication and disease comes from the natural hosts of SIV infection, in which high viral loads of 104-105 copies/ml of SIV are associated with a normal life span, normal CD4 counts and low immune activation in non-human primates such as the sooty mangabey or African green monkey (11).

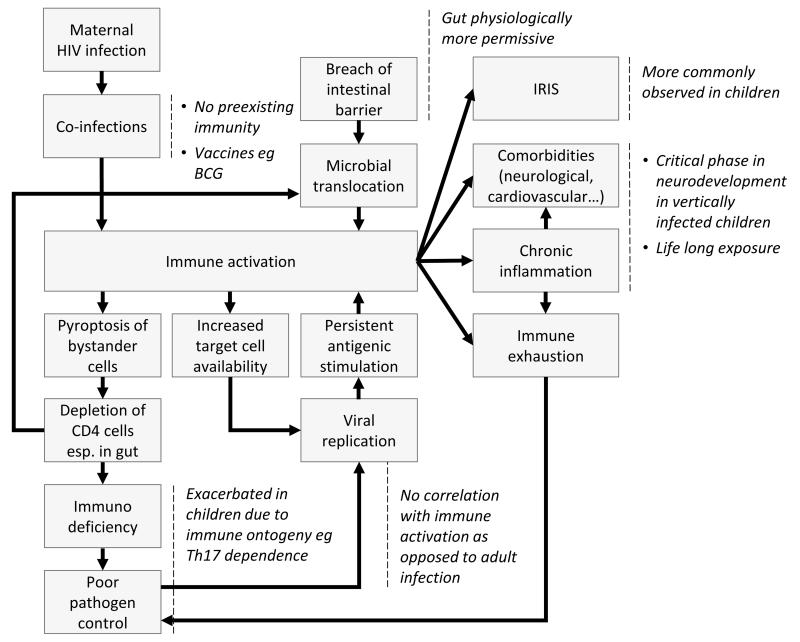

Persistent systemic immune activation is believed to play a key role in HIV pathogenesis as a result of depletion of CD4+ cells in a vicious circle of inflammation partially triggered by microbial translocation (12), leading to immune activation, increased numbers of CD4+ T-cells susceptible to infection, and activation-induced cell death through apoptosis and pyroptosis of bystander cells (13, 14) **. Please see Figure 1 for further illustration. The structural damage to the gut caused by CD4 depletion, and viral replication resulting from infection of increased numbers of susceptible targets cells maintains the cycle. A second important observation is that, although immune activation levels are decreased following successful suppression of viral replication by anti-retroviral therapy (ART), these remain higher than in uninfected controls (10). The consequence already being observed in ART-treated, HIV-infected adults are the diseases associated with ageing, such as cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular accidents and cancers (15, 16). HIV-infected children, therefore, even if successfully treated with ART, face a lifetime of elevated immune activation. Thus, evaluating the potential impact of chronic immune activation and inflammation on the developing immune system and on disease outcome in paediatric HIV infection is of particular importance, as the numbers of ART-treated HIV-infected children grows exponentially (UNAIDS 2014), and survival to adulthood is now the norm.

Fig 1. The vicious cycle of inflammation in HIV infection, and features especially observed in paediatric infection.

Refer to the text for further elaboration.

Immune activation, viral load and disease progression in paediatric and adult infection

Immune activation is a stronger prognostic indicator of disease outcome than viral load in adult infection (17, 18). It has been reported that immune activation as early as 1-2 months of age can predict which children will become long-term non-progressors (19). A striking difference between adult and paediatric infection is that CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation is significantly associated with CD4+ percentage and absolute CD4 count but not with viral load (20, 21) whereas in adult infection the two (immune activation and viral load) are strongly correlated (22). Again in contrast to adults, viral load itself is not a strong predictor of disease progression in infants (23, 24). Viral set point is only established after several years of infection as opposed to a few weeks in adult infection (25, 26) and there is a substantial overlap in viral loads between children who progress and those who do not progress to disease (24, 27). Hence, the relationship between viral load and immune activation is weaker in children than in adults (17, 19, 21, 28, 29).

Although normal CD4 counts in adult HIV infection are typically associated with low viral loads, a rare subset of ART-naïve adults have stable CD4 counts that are maintained despite persistent high viral setpoints of 104-105 copies/ml (30-34) (34)**. This phenotype of high viral loads and high CD4 counts is more typical in non-progressing paediatric than adult infection (35). In non-progressing paediatric infection, high viral loads are associated with low levels of immune activation (35). Studies of adult viremic non-progressors (AVNP) have been somewhat compromised by the extreme rarity of these subjects (study numbers ranging from between 3 in the smallest and 9 in the largest analysis) and among these there is some disagreement over whether immune activation is also decreased in the AVNPs (30, 31, 33, 34)(34)**. In AVNPs there is lower expression of interferon-stimulated genes despite high viral loads (31). This phenotype in non-progressing paediatric infection and in AVNP is therefore reminiscent of that described above in relation to the natural hosts of SIV infection, such as sooty mangabeys and African green monkeys (11, 36). Overall some 40 non-human primates appear to have evolved an immune strategy against SIV infection that employs minimal engagement of the adaptive immune response with the virus (37), in complete contrast to what is observed in typical HIV infection. However, the mechanisms by which, on the one hand, viral load, and on the other, low immune activation and high CD4 counts, are dislocated in AVNPs and non-progressing children, remained to be fully defined.

Microbial translocation and immune activation in children

Microbial translocation through the gut is a major contributor of ongoing chronic immune activation (12). The cause of microbial translocation is the concentration of activated CD4+ CCR5+ T-cells in the gastrointestinal tract that are highly susceptible to HIV infection. In the SIV model of pathogenic HIV infection, 70% of intestinal CD4+ T-cells are depleted within 3 weeks of infection (38, 39). This results not only in the loss of CD4+ T-cell function but also in structural damage to the intestinal mucosal barrier.

In particular, Th17 CD4+ T-cells play a key structural role in maintenance of the mucosal epithelium, in addition to their immune function in host defense against extracellular pathogens. However, Th17 CD4+ T-cells are preferentially lost in pathogenic HIV and SIV infection (40, 41). There is a hint from studies of nonpathogenic SIV infection that Th17 cells play a critical part in shaping the pattern of ongoing immune activation and thereby ultimately in determining whether the infection is pathogenic. Like adult HIV infection and SIV infection in the Indian rhesus macaque, acute SIV infection in sooty mangabeys and African green monkeys results in severe depletion of the CD4+ T-cells in the gut mucosa (42, 43). However, in contrast, in non-pathogenic SIV infection Th17 CD4+ T-cells in the gut are maintained at normal levels (44), suggesting that these cells may be especially important in limiting microbial translocation.

These considerations of the factors that may contribute to high levels of immune activation in pathogenic HIV and SIV infection highlight the specific challenges facing infected children. The infant intestinal epithelium is physiologically more permissive to antigens than that of adults, and especially so in the case of children born prematurely. One-third of babies born to HIV-infected mothers are born before 37 weeks gestation (45). Consequently, markers of microbial translocation are elevated compared to adults both in HIV-infected children as well as in HIV-negative controls in early life (46, 47). Additional factors such as low birth-weight, and the gut microbiome, influence the degree of microbial translocation (48, 49). Factors increasing the levels of immune activation in infants include the use of chronic broad-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis (48), in addition to other alterations in the diet (50). The maternal influence on immune activation in the child is indicated by the finding that, compared to unexposed uninfected infants, HIV-exposed uninfected neonates show lower CD4+ counts and enhanced levels of immune activation (51). Furthermore the demonstration in the human fetal intestine of large numbers of CD4+CCR5+ T cells, including those with Th17 phenotypes, indicates that infants are indeed susceptible to in utero and/or peri-partum HIV-1 infection (52) and to the vicious cycle of events described above that follow from loss of CD4+ T-cells from the intestinal mucosa. As in adult infection, many studies have shown HIV-infected ART-naïve children show increased levels of plasma markers of microbial translocation (sCD14, LPS, 16srDNA) when compared to healthy controls, the highest levels being observed in the most severely immune-compromised children (46, 47, 53-55). As in adults, these raised levels of immune activation are not fully suppressed by ART.

Impact of maternal factors on immune activation in the child

It has long been known that disease progression in HIV-infected children is correlated with maternal health status at delivery (2, 56-59). Thus, in addition to the fact that HIV-infected children are infected earlier in life compared to adults, paediatric infection also differs in factors related to host genetics, host immunity, to the transmitted virus, and to the environment shared between mother and child.

Influence of maternal breast milk and maternal antibody transmission

Breast milk itself, which contains factors such as lactoferrin and TGF-b, may contribute to the maintained integrity of the epithelial barrier and to reduced microbial translocation (48). However, as mentioned above in relation to the presence of prophylactic antibiotics, the diet has a major impact on the composition of gut microbiota, disruption of which may lead to mucosal inflammation and increased microbial translocation. It is apparent that the risk of mother-to-child transmission via breast-milk is significantly lower when breast-feeding is exclusive of supplementary feeding from formula, other liquids, and solids (60-63). The underlying reason for this remains unknown but the impact of an ever-changing diet on the gut microbiota, in addition to the introduction of unsterilized water, is likely to result in increased gut inflammation, an increased risk of infection and increased microbial translocation. Even in mothers who are exclusively breast-feeding, it is likely that the health status of the mother may affect the quality of her breast milk, and therefore impact on the gut microbiome, as well as the general nutritional status, of the infant. Furthermore, breast-feeding increases the risk of infections other than HIV, such as CMV, that will increase immune activation. The fact that the mother has transmitted HIV to the child means that she is likely to have a high viral load and a low CD4 count (64, 65) and therefore herself is at high risk of the range of opportunistic infections associated with HIV, most commonly TB. The impact of co-infections on immune activation in the child is discussed further below.

Finally, maternal antibodies are transmitted both in breast milk and transplacentally. Protection against mortality resulting from gastro-intestinal and respiratory tract infections in breast-fed infants explains the paradoxical benefit of exclusive breast-feeding in babies, whether HIV infected or not, born to HIV-infected mothers (60-63). In contrast, transmission of HIV-specific antibodies across the placenta do not appear to influence paediatric disease outcome, for the reason that maternal antibodies against transmitted viruses are non-neutralizing (65, 66).

Influence of maternal genetics

Among the host genetics relevant to HIV immune activation that are shared by mother and child, most notable are the HLA genes. The particular HLA class I genes expressed have a major impact on disease outcome in adult infection. In particular, alleles such as HLA-B*27, HLA-B*57, HLA-B*58:01, and HLA-B*81:01 are associated with protection against rapid progression, whereas HLA-B*18:01, HLA-B*35, HLA-B*45:01 and HLA-B*58:02 are associated with rapid progression (67). Since MTCT is associated with high maternal viral load (64, 65) this explains the observation that transmitting mothers are more likely to express HLA class I alleles associated with rapid progression (68). In turn, because the children inherit half the HLA genes from the mother, HIV-infected children start with an apparent HLA disadvantage compared to HIV-infected adult recipients. Furthermore, the transmitted virus is likely to be adapted to maternally inherited HLA genes. Alternatively, if MTCT follows acute infection in the mother during pregnancy, the virus transmitted to the child may be adapted to the paternally inherited HLA genes. Transmission of pre-adapted strains of virus significantly undermines the ability of the immune system to control HIV replication (69-71).

The relatively low expression in infected children of HLA class I genes that are protective in adult infection may not, however, be as disadvantageous as it at first appears. Low immune activation in non-progressing adult infection is typically the result of a strong, broadly directed, HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell response against HIV that is restricted by these protective HLA class I molecules such as HLA-B*27/57/58:01/81:01 (67). In a subset of these individuals viral replication is successfully suppressed and immune activation reduced to low levels. In the majority of cases, however, the virus ‘wins’ this contest, and the aggressive immune response adopted in adult infection does not succeed. In HIV-infected infants expressing these ‘protective’ HLA alleles, the same HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell responses may be generated against the virus, but owing to the factors relating to immune ontogeny described above, these responses usually have no impact on viral replication, or on disease outcome generally in paediatric infection (72) **. In the interest of minimizing immune activation, therefore, it may be a more successful strategy in paediatric infection to make no adaptive immune response against the virus.

In contrast, it has been suggested that HLA alleles such as HLA-B*35, that are normally associated with disease-susceptibility in adult infection, may contribute to the phenomenon of post-treatment control, as illustrated in the so-called Visconti cohort (73). A possible mechanism here may relate to the differential avidity of HLA molecules to bind to leucocyte immunoglobulin-like receptors, such as LILR-B2, that are expressed mainly on myelomonocytic such as dendritic cells (74)*. Disease protective HLA such as HLA-B*27/57/58:01 bind relatively weakly to LILRB2,* whereas disease-susceptible alleles such as HLA-B*35/45:01 bind with high avidity. This may interfere with the ability of virus-infected cells to prime CD8+ T-cells, either directly, or as a result of a regulatory role of LILRB2 binding to DCs. In this latter case, higher avidity HLA-LILRB2 interactions result in altered DC cytokine production and lower immune activation (75).

Influence of transmitted virus

As described above, HIV-infected children are more likely than adults to be recipients of a transmitted virus that is highly adapted to autologous HLA class I molecules. This is likely to reduce the HIV-specific epitopes available for CD8+ T-cell recognition. However, perhaps more importantly in the case of paediatric infection, there may be effects of multiple escape mutants on viral replicative capacity that will have a greater and more direct impact on immune activation. In adults, transmission of viruses with high viral replicative capacity (VRC) result in a pattern of response in recipients characterized by high immune activation and rapid disease progression, effects that were independent of viral load (76)**.

Furthermore, virus with high VRC tended to be localized within naïve and central memory CD4+ T-cell compartments, characteristic of pathogenic infection. Whilst it is clear that viruses with higher VRC tend to be favored in adult transmission (77)*, transmission of HIV across the placenta may involve distinct mechanisms. Strategies designed to prevent MTCT have tended to be most successful at blocking intra-partum and post-partum transmission, therefore increasing the proportion of transmissions that arise in utero (for example, see (78)), and it is notable that in the limited studies undertaken to date, VRC of the virus transmitted to the child (recipient) tends to be lower than in the infected mother (donor) (72, 79) – the opposite of that observed in adult transmission (77)*.

This scenario prompts the hypothesis that certain viral adaptations might be required to enable virus to cross the placental barrier, which however reduce VRC post-transmission. If this were the case, this would represent an additional factor favoring low immune activation in paediatric infection.

Co-infections, vaccinations and immune activation

It is evident that infancy and early childhood is characterized by a stream of new infections that are an inevitable rite of passage from birth into the outside world. Maternal antibody, especially in breast-fed infants, delays the onset of many common infections until the latter part of the first year. However some infections are not prevented by maternal antibody, the most prominent being CMV. In sub-Saharan Africa, almost two-thirds of infants have become infected by 3 months of age, and 85% by 12 months (80). CMV infection is associated with increased immune activation in HIV-uninfected and co-infected children (80, 81). As might be expected, CMV/HIV co-infected in children is associated with more rapid disease progression and greater morbidity, including impaired brain growth and/or motor deficits (82).

Other important diseases of childhood that are not prevented by maternal antibody are those incorporated into the vaccine schedule. Most notable amongst these is BCG, which in addition to having specific effects of reducing TB infection and disease, such as military TB and TB meningitis (83, 84), has non-specific beneficial effects in protection against non-mycobacterial pathogens (85-87). The non-specific effects of BCG appear to be mediated via epigenetic histone methylation of the NOD2 gene, resulting in increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 (88, 89). Certainly in relation to HIV infection it is clear that BCG increases immune activation and escalates the risk of infection and of disease progression in infected children (90)*. However, not only active but also latent TB infection increases immune activation in HIV-infected individuals (91). Thus there are significant beneficial and detrimental effects of BCG, the balance between which may depend on the particular setting and population. New TB vaccination strategies are currently being actively explored (90)*.

Immune activation and ART and in paediatric infection

As described in adult infection, ART-treated children demonstrate reduced levels of immune activation that, however, do not reach those of uninfected controls (1, 20, 55, 92). It is clear that early ART reduces the size of the latent HIV reservoir both in paediatric and adult infection (93, 94). Recently it has been shown that immune activation (HLA-DR, CD38) and exhaustion markers (Tim-3, PD-1, Lag-3) are strongly associated with reservoir size in ART-treated adults, the latter predicting duration of post-treatment control (that is, after ART is discontinued) (95)**. Thus it might be anticipated that minimizing the viral reservoir with early ART might, equally, minimize the level of immune activation and the non-AIDS ‘ageing’ diseases associated with persistent immune activation. In paediatric infection there is some suggestion that early ART may be especially effective in bringing reservoirs down to a level from which future eradication efforts might be effective. This follows on from the anecdotal case of the Mississippi child, who maintained aviremia for >2yrs having initiated ART at 30hrs of age, and discontinued ART approximately 19 months later (96, 97). More recently the anecdotal case of a ‘Visconti’ child was reported, who had maintained aviremia for 12 years having discontinued ART at 6 years of age (98). The tolerogenic immune environment that exists in newborns and through early life, together with the relative paucity of activated memory CD4+ T-cells in the blood that are the targets of HIV infection (52), may tend to prevent the vicious cycle of immune activation that is observed in adult infection, and thereby limit the ability of the virus to establish an extensive viral reservoir of infection. Having said this, as described above, an abundance of activated CCR5+ CD4+ T-cells are present in the fetal gut, and so any limitations the in utero environment impose on the ability of HIV to establish reservoirs of infection in long-lived, latently infected CD4+ T-cells, are only relative.

CONCLUSIONS

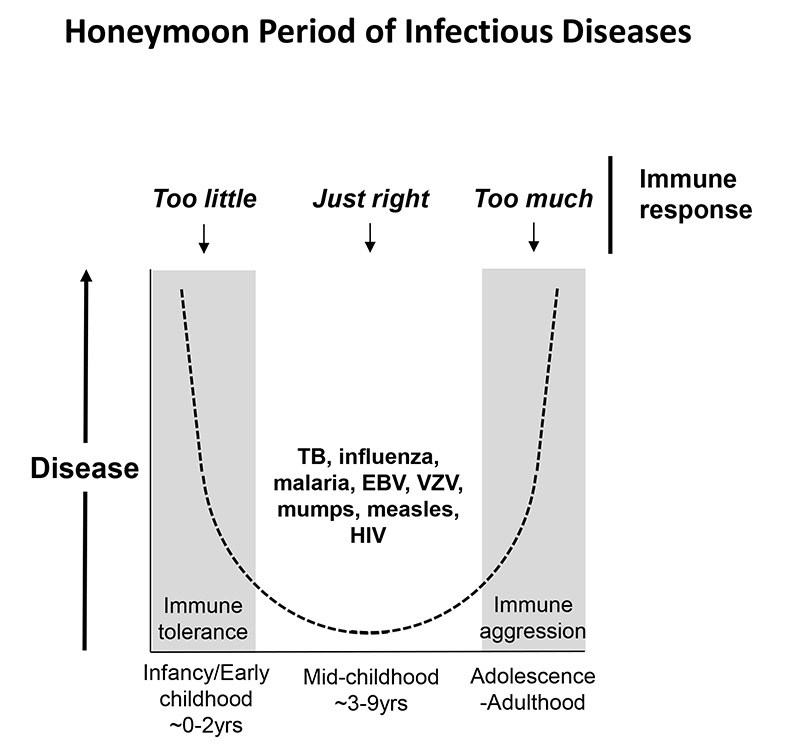

HIV infection illustrates the fine line between too weak an immune response, which leaves the host susceptible to pathogen-mediated disease; and too strong an immune response, which leaves the host vulnerable to immunopathology. The immune response in-utero and in early life has been adapted over the course of evolution to adopt a tolerogenic environment, and a Th2/Th17-biased adaptive immune response. In adulthood, the immune response is broadly pro-inflammatory and Th1 CD4 T-cell driven. Between these two extremes, lies the so-called ‘honeymoon’ period of infectious diseases (99), in which, during the middle years of childhood, disease and mortality from a range of infections is less than in infancy and early childhood, and also less than in adolescence and adulthood (Figure 2) (99, 100). Examples include TB disease (101), influenza (102), malaria (103), glandular fever (EBV), chicken pox (VZV), mumps, measles – and HIV (104, 105). In the case of HIV, however, it appears that there are two distinct immune strategies that can be successful. In the adults, an aggressive immune response driven by broadly-based CD8+ T-cell responses restricted by protective class I HLA molecules such as HLA-B*57 can, in a minority of cases, suppress viremia and achieve ‘elite’ control. In the small subset of non-progressing children, disengagement with the virus by the adaptive immune response, perhaps in a manner adopted by the natural hosts of SIV infection, results in no containment whatsoever of the virus, but without immune activation, and therefore without disease. The problem for most children infected with HIV, therefore, in the first months and early years of life is not that they do not engage sufficiently with the virus, but that they engage too much. In part this may be a consequence of gut immaturity, and the consequences of microbial translocation that over-ride the bias of the tolerogenic state of immune ontogeny towards low immune activation. Defining the factors that in non-progressing children succeed in preventing the vicious cycle of HIV-driven immune activation to become established, becomes ever more important. Please see Table 1/Box for summary of the specific features of immune activation in paediatric HIV infection.

Fig 2. Model of the ‘honeymoon’ period of infectious disease in childhood.

(99) In early childhood, and also in adolescence-adulthood, disease and mortality from infections such as TB, influenza, malaria, EBV, VZV, mumps, measles and HIV are greater than in mid-childhood. This honeymoon period may represent the phase between ‘tolerance’ and ‘aggression’ of the immune response (100) when the immune response is perfectly balanced to engage successfully with the pathogen and yet minimize immunopathology. In HIV infection, the optimal strategy in paediatric infection may be to minimize engagement with the virus (see text).

Table/Box. Features specific to paediatric HIV infection in relation to immune activation.

Timing of HIV infection

|

Transmitter is HIV-infected mother

|

Summary in key bullets.

The timing of paediatric HIV infection has two opposing effects in relation to immune activation. Immune ontogeny predisposes towards low immune activation in utero and in early life. In contrast, immaturity of the gut at these stages of development results in increased microbial translocation even in HIV-uninfected infants.

A key factor in paediatric infection initiating the vicious cycle of inflammation may be the disproportionate infection of Th17 CD4+ T-cells in the gut, cells upon which infants depend both functionally for defence against extracellular pathogens, but also structurally for maintained integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier.

Maternal factors have a strong influence on immune activation and disease outcome in paediatric HIV infection. These include the nature of infant feeding on intestinal microbiota, antibody transmission in breast-milk and transplacentally, transmission of infections such as CMV and TB, the impact of shared genetics such as HLA class I haplotypes, the transmission of pre-adapted viruses from mother-to-child, and the impact of viral replicative capacity on immune activation in the child recipient.

Infancy and early life is characterized by exposure to a range of new pathogens, in particular, in HIV-infected children, CMV and TB, all of which to varying degrees increase immune activation. Vaccinations may have a similar impact. The benefits of BCG-mediated protection against severe TB disease, and of the non-specific effects of this vaccine are finely balanced against the disadvantages by the increased risk of HIV infection and more rapid disease progression it also brings.

Acknowledgements

None

Financial support and sponsorship – Nil [PJRG is a Wellcome Trust Investigator]

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest - none

References

- 1.De Rossi A, Masiero S, Giaquinto C, Ruga E, Comar M, Giacca M, et al. Dynamics of viral replication in infants with vertically acquired human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(2):323–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI118419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newell ML, Coovadia H, Cortina-Borja M, Rollins N, Gaillard P, Dabis F, et al. Mortality of infected and uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Africa: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2004;364(9441):1236–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prendergast AJ, Klenerman P, Goulder PJ. The impact of differential antiviral immunity in children and adults. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(9):636–48. doi: 10.1038/nri3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tobin NH, Aldrovandi GM. Are infants unique in their ability to be “functionally cured” of HIV-1? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kollmann TR, Crabtree J, Rein-Weston A, Blimkie D, Thommai F, Wang XY, et al. Neonatal innate TLR-mediated responses are distinct from those of adults. J Immunol. 2009;183(11):7150–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godfrey WR, Spoden DJ, Ge YG, Baker SR, Liu B, Levine BL, et al. Cord blood CD4(+)CD25(+)-derived T regulatory cell lines express FoxP3 protein and manifest potent suppressor function. Blood. 2005;105(2):750–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy O. Innate immunity of the newborn: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(5):379–90. doi: 10.1038/nri2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mold JE, Michaelsson J, Burt TD, Muench MO, Beckerman KP, Busch MP, et al. Maternal alloantigens promote the development of tolerogenic fetal regulatory T cells in utero. Science. 2008;322(5907):1562–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1164511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muenchhoff M, Prendergast AJ, Goulder PJ. Immunity to HIV in Early Life. Front Immunol. 2014;5:391. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt PW, Brenchley J, Sinclair E, McCune JM, Roland M, Page-Shafer K, et al. Relationship between T cell activation and CD4+ T cell count in HIV-seropositive individuals with undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(1):126–33. doi: 10.1086/524143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silvestri G, Sodora DL, Koup RA, Paiardini M, O'Neil SP, McClure HM, et al. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity. 2003;18(3):441–52. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12(12):1365–71. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doitsh G, Galloway NL, Geng X, Yang Z, Monroe KM, Zepeda O, et al. Cell death by pyroptosis drives CD4 T-cell depletion in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 2014;505(7484):509–14. doi: 10.1038/nature12940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Refs 13 and 14 **This study and ref 14 describe a major cause of HIV-uninfected CD4 T-cell loss in HIV infection via the pyroptotic pathway.

- 14.Monroe KM, Yang Z, Johnson JR, Geng X, Doitsh G, Krogan NJ, et al. IFI16 DNA sensor is required for death of lymphoid CD4 T cells abortively infected with HIV. Science. 2014;343(6169):428–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1243640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy Study G. El-Sadr WM, Lundgren J, Neaton JD, Gordin F, Abrams D, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(22):2283–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Group ISS. Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, et al. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giorgi JV, Hultin LE, McKeating JA, Johnson TD, Owens B, Jacobson LP, et al. Shorter survival in advanced human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection is more closely associated with T lymphocyte activation than with plasma virus burden or virus chemokine coreceptor usage. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(4):859–70. doi: 10.1086/314660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deeks SG, Kitchen CM, Liu L, Guo H, Gascon R, Narvaez AB, et al. Immune activation set point during early HIV infection predicts subsequent CD4+ T-cell changes independent of viral load. Blood. 2004;104(4):942–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul ME, Mao C, Charurat M, Serchuck L, Foca M, Hayani K, et al. Predictors of immunologic long-term nonprogression in HIV-infected children: implications for initiating therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(4):848–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ssewanyana I, Elrefaei M, Dorsey G, Ruel T, Jones NG, Gasasira A, et al. Profile of T cell immune responses in HIV-infected children from Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(11):1667–70. doi: 10.1086/522013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prendergast A, O'Callaghan M, Menson E, Hamadache D, Walters S, Klein N, et al. Factors influencing T cell activation and programmed death 1 expression in HIV-infected children. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28(5):465–8. doi: 10.1089/AID.2011.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, Brown JA, Moodley ES, Reddy S, et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature. 2006;443(7109):350–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrams EJ, Weedon J, Steketee RW, Lambert G, Bamji M, Brown T, et al. Association of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) load early in life with disease progression among HIV-infected infants. New York City Perinatal HIV Transmission Collaborative Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(1):101–8. doi: 10.1086/515596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shearer WT, Quinn TC, LaRussa P, Lew JF, Mofenson L, Almy S, et al. Viral load and disease progression in infants infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Women and Infants Transmission Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(19):1337–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705083361901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ofori-Mante JA, Kaul A, Rigaud M, Fidelia A, Rochford G, Krasinski K, et al. Natural history of HIV infected paediatric long-term or slow progressor population after the first decade of life. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(3):217–20. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000254413.11246.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McIntosh K, Shevitz A, Zaknun D, Kornegay J, Chatis P, Karthas N, et al. Age- and time-related changes in extracellular viral load in children vertically infected by human immunodeficiency virus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15(12):1087–91. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biggar RJ, Broadhead R, Janes M, Kumwenda N, Taha TE, Cassol S. Viral levels in newborn African infants undergoing primary HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2001;15(10):1311–3. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mekmullica J, Brouwers P, Charurat M, Paul M, Shearer W, Mendez H, et al. Early immunological predictors of neurodevelopmental outcomes in HIV-infected children. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(3):338–46. doi: 10.1086/595885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Resino S, Seoane E, Gutierrez MD, Leon JA, Munoz-Fernandez MA. CD4(+) T-cell immunodeficiency is more dependent on immune activation than viral load in HIV-infected children on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(3):269–76. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000222287.90201.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choudhary SK, Vrisekoop N, Jansen CA, Otto SA, Schuitemaker H, Miedema F, et al. Low immune activation despite high levels of pathogenic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 results in long-term asymptomatic disease. J Virol. 2007;81(16):8838–42. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02663-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotger M, Dalmau J, Rauch A, McLaren P, Bosinger SE, Martinez R, et al. Comparative transcriptomics of extreme phenotypes of human HIV-1 infection and SIV infection in sooty mangabey and rhesus macaque. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2391–400. doi: 10.1172/JCI45235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curriu M, Fausther-Bovendo H, Pernas M, Massanella M, Carrillo J, Cabrera C, et al. Viremic HIV infected individuals with high CD4 T cells and functional envelope proteins show anti-gp41 antibodies with unique specificity and function. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw JM, Hunt PW, Critchfield JW, McConnell DH, Garcia JC, Pollard RB, et al. Short communication: HIV+ viremic slow progressors maintain low regulatory T cell numbers in rectal mucosa but exhibit high T cell activation. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(1):172–7. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klatt NR, Bosinger SE, Peck M, Richert-Spuhler LE, Heigele A, Gile JP, et al. Limited HIV infection of central memory and stem cell memory CD4+ T cells is associated with lack of progression in viremic individuals. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(8):e1004345. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Ref 34 The largest study of AVNP to date (n=9) demonstrates the lower level of HIV DNA in stem cell memory T-cells and central memory T-cells in AVNP compared to putative progressors, matched for CD4 count. This cellular localization of the viral reservoir is reminiscent of the arrangement in the sooty mangabey and African green monkey. Surprisingly immune activation levels were not lower in the AVNP in this study.

- 35.Adland E. Mechanisms of non-pathogenicity in HIV – Lessons from paediatric infection. IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chahroudi A, Bosinger SE, Vanderford TH, Paiardini M, Silvestri G. Natural SIV hosts: showing AIDS the door. Science. 2012;335(6073):1188–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1217550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunham R, Pagliardini P, Gordon S, Sumpter B, Engram J, Moanna A, et al. The AIDS resistance of naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys is independent of cellular immunity to the virus. Blood. 2006;108(1):209–17. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, Knight HL, et al. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 1998;280(5362):427–31. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kewenig S, Schneider T, Hohloch K, Lampe-Dreyer K, Ullrich R, Stolte N, et al. Rapid mucosal CD4(+) T-cell depletion and enteropathy in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(5):1115–23. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brenchley JM, Paiardini M, Knox KS, Asher AI, Cervasi B, Asher TE, et al. Differential Th17 CD4 T-cell depletion in pathogenic and nonpathogenic lentiviral infections. Blood. 2008;112(7):2826–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cecchinato V, Trindade CJ, Laurence A, Heraud JM, Brenchley JM, Ferrari MG, et al. Altered balance between Th17 and Th1 cells at mucosal sites predicts AIDS progression in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(4):279–88. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon SN, Klatt NR, Bosinger SE, Brenchley JM, Milush JM, Engram JC, et al. Severe depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells in AIDS-free simian immunodeficiency virus-infected sooty mangabeys. J Immunol. 2007;179(5):3026–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandrea IV, Gautam R, Ribeiro RM, Brenchley JM, Butler IF, Pattison M, et al. Acute loss of intestinal CD4+ T cells is not predictive of simian immunodeficiency virus virulence. J Immunol. 2007;179(5):3035–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Favre D, Lederer S, Kanwar B, Ma ZM, Proll S, Kasakow Z, et al. Critical loss of the balance between Th17 and T regulatory cell populations in pathogenic SIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(2):e1000295. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zack RM, Golan J, Aboud S, Msamanga G, Spiegelman D, Fawzi W. Risk Factors for Preterm Birth among HIV-Infected Tanzanian Women: A Prospective Study. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2014;2014:261689. doi: 10.1155/2014/261689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallet MA, Rodriguez CA, Yin L, Saporta S, Chinratanapisit S, Hou W, et al. Microbial translocation induces persistent macrophage activation unrelated to HIV-1 levels or T-cell activation following therapy. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1281–90. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339e228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papasavvas E, Azzoni L, Foulkes A, Violari A, Cotton MF, Pistilli M, et al. Increased microbial translocation in </= 180 days old perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-positive infants as compared with human immunodeficiency virus-exposed uninfected infants of similar age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(10):877–82. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31821d141e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kourtis AP, Ibegbu CC, Wiener J, King CC, Tegha G, Kamwendo D, et al. Role of intestinal mucosal integrity in HIV transmission to infants through breast-feeding: the BAN study. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(4):653–61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sherman MP. New concepts of microbial translocation in the neonatal intestine: mechanisms and prevention. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37(3):565–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen S, Nielsen DS, Lauritzen L, Jakobsen M, Michaelsen KF. Impact of diet on the intestinal microbiota in 10-month-old infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(5):613–8. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3180406a11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bunders MJ, van Hamme JL, Jansen MH, Boer K, Kootstra NA, Kuijpers TW. Fetal exposure to HIV-1 alters chemokine receptor expression by CD4+T cells and increases susceptibility to HIV-1. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6690. doi: 10.1038/srep06690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bunders MJ, van der Loos CM, Klarenbeek PL, van Hamme JL, Boer K, Wilde JC, et al. Memory CD4(+)CCR5(+) T cells are abundantly present in the gut of newborn infants to facilitate mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. Blood. 2012;120(22):4383–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pilakka-Kanthikeel S, Huang S, Fenton T, Borkowsky W, Cunningham CK, Pahwa S. Increased gut microbial translocation in HIV-infected children persists in virologic responders and virologic failures after antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(6):583–91. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31824da0f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pilakka-Kanthikeel S, Kris A, Selvaraj A, Swaminathan S, Pahwa S. Immune activation is associated with increased gut microbial translocation in treatment-naive, HIV-infected children in a resource-limited setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(1):16–24. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anselmi A, Vendrame D, Rampon O, Giaquinto C, Zanchetta M, De Rossi A. Immune reconstitution in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children with different virological responses to anti-retroviral therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150(3):442–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blanche S, Mayaux MJ, Rouzioux C, Teglas JP, Firtion G, Monpoux F, et al. Relation of the course of HIV infection in children to the severity of the disease in their mothers at delivery. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(5):308–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402033300502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lambert G, Thea DM, Pliner V, Steketee RW, Abrams EJ, Matheson P, et al. Effect of maternal CD4+ cell count, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and viral load on disease progression in infants with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. New York City Perinatal HIV Transmission Collaborative Study Group. J Pediatr. 1997;130(6):890–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tovo PA, de Martino M, Gabiano C, Galli L, Tibaldi C, Vierucci A, et al. AIDS appearance in children is associated with the velocity of disease progression in their mothers. J Infect Dis. 1994;170(4):1000–2. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abrams EJ, Wiener J, Carter R, Kuhn L, Palumbo P, Nesheim S, et al. Maternal health factors and early paediatric antiretroviral therapy influence the rate of perinatal HIV-1 disease progression in children. AIDS. 2003;17(6):867–77. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304110-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coutsoudis A, Pillay K, Kuhn L, Spooner E, Tsai WY, Coovadia HM, et al. Method of feeding and transmission of HIV-1 from mothers to children by 15 months of age: prospective cohort study from Durban, South Africa. AIDS. 2001;15(3):379–87. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coovadia HM, Rollins NC, Bland RM, Little K, Coutsoudis A, Bennish ML, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 infection during exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life: an intervention cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369(9567):1107–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iliff PJ, Piwoz EG, Tavengwa NV, Zunguza CD, Marinda ET, Nathoo KJ, et al. Early exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of postnatal HIV-1 transmission and increases HIV-free survival. AIDS. 2005;19(7):699–708. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000166093.16446.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuhn L, Sinkala M, Kankasa C, Semrau K, Kasonde P, Scott N, et al. High uptake of exclusive breastfeeding and reduced early post-natal HIV transmission. PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sperling RS, Shapiro DE, Coombs RW, Todd JA, Herman SA, McSherry GD, et al. Maternal viral load, zidovudine treatment, and the risk of transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from mother to infant. paediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(22):1621–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611283352201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dickover RE, Garratty EM, Herman SA, Sim MS, Plaeger S, Boyer PJ, et al. Identification of levels of maternal HIV-1 RNA associated with risk of perinatal transmission. Effect of maternal zidovudine treatment on viral load. JAMA. 1996;275(8):599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu X, Parast AB, Richardson BA, Nduati R, John-Stewart G, Mbori-Ngacha D, et al. Neutralization escape variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are transmitted from mother to infant. J Virol. 2006;80(2):835–44. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.835-844.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goulder PJ, Walker BD. HIV and HLA class I: an evolving relationship. Immunity. 2012;37(3):426–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goulder PJ, Brander C, Tang Y, Tremblay C, Colbert RA, Addo MM, et al. Evolution and transmission of stable CTL escape mutations in HIV infection. Nature. 2001;412(6844):334–8. doi: 10.1038/35085576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goepfert PA, Lumm W, Farmer P, Matthews P, Prendergast A, Carlson JM, et al. Transmission of HIV-1 Gag immune escape mutations is associated with reduced viral load in linked recipients. J Exp Med. 2008;205(5):1009–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carlson JM, Le AQ, Shahid A, Brumme ZL. HIV-1 adaptation to HLA: a window into virus-host immune interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23(4):212–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crawford H, Lumm W, Leslie A, Schaefer M, Boeras D, Prado JG, et al. Evolution of HLA-B*5703 HIV-1 escape mutations in HLA-B*5703-positive individuals and their transmission recipients. J Exp Med. 2009;206(4):909–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Adland E, Paioni P, Thobakgale C, Laker L, Mori L, Muenchhoff M, et al. Discordant Impact of HLA on Viral Replicative Capacity and Disease Progression in paediatric and Adult HIV Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(6):e1004954. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Ref 72 This study is the largest to date of non-progressing paediatric HIV infection and highlights the relatively insignificant role of HLA class I in this group compared to non-progressing adult infection. As in adults, viral replicative capacity is associated with disease progression rates but other factors contribute. Curiously, in contrast to adult donor-recipient pairs, viral replicative capacity in the child tended to be lower than in the mother.

- 73.Saez-Cirion A, Bacchus C, Hocqueloux L, Avettand-Fenoel V, Girault I, Lecuroux C, et al. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(3):e1003211. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bashirova AA, Martin-Gayo E, Jones DC, Qi Y, Apps R, Gao X, et al. LILRB2 interaction with HLA class I correlates with control of HIV-1 infection. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(3):e1004196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Ref 74 This study intriguingly highlights a potential mechanism by which HLA class I molecules normally associated with rapid adult progression may be associated with post-treatment control, as a result of high avidity binding to LILRB2. This may also have relevance in HIV-infected children in whom these disease-susceptible HLA are enriched.

- 75.Huang J, Goedert JJ, Sundberg EJ, Cung TD, Burke PS, Martin MP, et al. HLA-B*35-Px-mediated acceleration of HIV-1 infection by increased inhibitory immunoregulatory impulses. J Exp Med. 2009;206(13):2959–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Claiborne DT, Prince JL, Scully E, Macharia G, Micci L, Lawson B, et al. Replicative fitness of transmitted HIV-1 drives acute immune activation, proviral load in memory CD4+ T cells, and disease progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(12):E1480–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421607112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Ref 76 This study of Zambian adult transmission pairs identifies a link between the replication capacity of transmitted virus and levels of immune activation – independent of viral load effect - in the recipient.

- 77.Carlson JM, Schaefer M, Monaco DC, Batorsky R, Claiborne DT, Prince J, et al. HIV transmission. Selection bias at the heterosexual HIV-1 transmission bottleneck. Science. 2014;345(6193):1254031. doi: 10.1126/science.1254031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Ref 77This study demonstrates that viruses with higher replication capacity tend to be transmitted in adult infection.

- 78.Mphatswe W, Blanckenberg N, Tudor-Williams G, Prendergast A, Thobakgale C, Mkhwanazi N, et al. High frequency of rapid immunological progression in African infants infected in the era of perinatal HIV prophylaxis. AIDS. 2007;21(10):1253–61. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281a3bec2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Naidoo V. Mother to Child HIV Transmission is associated with a Gag-Protease-driven Viral Fitness Bottleneck. CROI- Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miles DJ, van der Sande M, Jeffries D, Kaye S, Ismaili J, Ojuola O, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in Gambian infants leads to profound CD8 T-cell differentiation. J Virol. 2007;81(11):5766–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00052-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bekker V, Bronke C, Scherpbier HJ, Weel JF, Jurriaans S, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, et al. Cytomegalovirus rather than HIV triggers the outgrowth of effector CD8+CD45RA+CD27- T cells in HIV-1-infected children. AIDS. 2005;19(10):1025–34. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000174448.25132.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kovacs A, Schluchter M, Easley K, Demmler G, Shearer W, La Russa P, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection and HIV-1 disease progression in infants born to HIV-1-infected women. paediatric Pulmonary and Cardiovascular Complications of Vertically Transmitted HIV Infection Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(2):77–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907083410203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trunz BB, Fine P, Dye C. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2006;367(9517):1173–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roy A, Eisenhut M, Harris RJ, Rodrigues LC, Sridhar S, Habermann S, et al. Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g4643. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aaby P, Roth A, Ravn H, Napirna BM, Rodrigues A, Lisse IM, et al. Randomized trial of BCG vaccination at birth to low-birth-weight children: beneficial nonspecific effects in the neonatal period? J Infect Dis. 2011;204(2):245–52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shann F. The nonspecific effects of vaccines and the expanded program on immunization. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(2):182–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Prentice S, Webb EL, Dockrell HM, Kaleebu P, Elliott AM, Cose S. Investigating the non-specific effects of BCG vaccination on the innate immune system in Ugandan neonates: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:149. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0682-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kleinnijenhuis J, Quintin J, Preijers F, Joosten LA, Ifrim DC, Saeed S, et al. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(43):17537–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202870109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wen H, Dou Y, Hogaboam CM, Kunkel SL. Epigenetic regulation of dendritic cell-derived interleukin-12 facilitates immunosuppression after a severe innate immune response. Blood. 2008;111(4):1797–804. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tchakoute CT, Hesseling AC, Kidzeru EB, Gamieldien H, Passmore JA, Jones CE, et al. Delaying BCG vaccination until 8 weeks of age results in robust BCG-specific T-cell responses in HIV-exposed infants. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(3):338–46. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Ref 90 This study, together with the correspondence following it, highlights the fine balance between the advantages and disadvantages of the BCG vaccination in a setting where both HIV and TB prevalence are exceptionally high.

- 91.Sullivan ZA, Wong EB, Ndung'u T, Kasprowicz VO, Bishai WR. Latent and Active Tuberculosis Infection Increase Immune Activation in Individuals Co-Infected with HIV. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(4):334–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cotugno N, Douagi I, Rossi P, Palma P. Suboptimal immune reconstitution in vertically HIV infected children: a view on how HIV replication and timing of HAART initiation can impact on T and B-cell compartment. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:805151. doi: 10.1155/2012/805151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Persaud D, Palumbo PE, Ziemniak C, Hughes MD, Alvero CG, Luzuriaga K, et al. Dynamics of the resting CD4(+) T-cell latent HIV reservoir in infants initiating HAART less than 6 months of age. AIDS. 2012;26(12):1483–90. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283553638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Buzon MJ, Martin-Gayo E, Pereyra F, Ouyang Z, Sun H, Li JZ, et al. Longterm antiretroviral treatment initiated at primary HIV-1 infection affects the size, composition, and decay kinetics of the reservoir of HIV-1-infected CD4 T cells. J Virol. 2014;88(17):10056–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01046-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hurst J, Hoffmann M, Pace M, Williams JP, Thornhill J, Hamlyn E, et al. Immunological biomarkers predict HIV-1 viral rebound after treatment interruption. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **Ref 95 The hypothesis that some HIV-infected individuals might become post-treatment controllers of HIV infection, following early initiation of ART and its subsequent discontinuation, has gained traction, both in adult and paediatric HIV infection. Defining which individuals will fail and which will succeed following ART discontinuation becomes critical question. This study on the SPARTAC cohort identifies PD-1, Tim-3 and Lag-3 prior to ART as markers that strongly predict time to viremic rebound.

- 96.Persaud D, Gay H, Ziemniak C, Chen YH, Piatak M, Jr., Chun TW, et al. Absence of detectable HIV-1 viremia after treatment cessation in an infant. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1828–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Luzuriaga K, Gay H, Ziemniak C, Sanborn KB, Somasundaran M, Rainwater-Lovett K, et al. Viremic relapse after HIV-1 remission in a perinatally infected child. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):786–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1413931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Saez-Cirion A. CROI- Conference of Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ahmed R, Oldstone MB, Palese P. Protective immunity and susceptibility to infectious diseases: lessons from the 1918 influenza pandemic. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(11):1188–93. doi: 10.1038/ni1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mold JE, McCune JM. At the crossroads between tolerance and aggression: Revisiting the “layered immune system” hypothesis. Chimerism. 2011;2(2):35–41. doi: 10.4161/chim.2.2.16329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, Hesseling AC, Obihara CC, Nelson LJ, et al. The clinical epidemiology of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(3):278–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Langford C. The age pattern of mortality in the 1918-19 influenza pandemic: an attempted explanation based on data for England and Wales. Med Hist. 2002;46(1):1–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Murray CJ, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS, Andrews KG, Foreman KJ, Haring D, et al. Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9814):413–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Darby SC, Ewart DW, Giangrande PL, Spooner RJ, Rizza CR. Importance of age at infection with HIV-1 for survival and development of AIDS in UK haemophilia population. UK Haemophilia Centre Directors' Organisation. Lancet. 1996;347(9015):1573–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Marinda E, Humphrey JH, Iliff PJ, Mutasa K, Nathoo KJ, Piwoz EG, et al. Child mortality according to maternal and infant HIV status in Zimbabwe. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(6):519–26. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000264527.69954.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]