Abstract

Background:

Good communication skills and rapport building are considered the cardinal tools for developing a patient-doctor relationship. A positive, healthy competition among different health care organizations in Saudi Arabia underlines an ever increasing emphasis on effective patient-doctor relationship. Despite the numerous guidelines provided and programs available, there is a significant variation in the acceptance and approach to the use of this important tool among pediatric residents in this part of the world.

Objective:

To determine pediatric residents' attitude toward communication skills, their perception of important communication skills, and their confidence in the use of their communication skills in the performance of their primary duties.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among all pediatrics trainee residents working in 13 different hospitals in Saudi Arabia. A standardized self-administered questionnaire developed by the Harvard Medical School was used.

Results:

A total of 297 residents out of all trainees in these centers participated in the data collection. The 283 (95%) residents considered learning communication skills a priority in establishing a good patient-doctor relationship. Thirty four percent reported being very confident with regard to their communication skills. Few residents had the skills, and the confidence to communicate with children with serious diseases, discuss end-of-life issues, and deal with difficult patients and parents.

Conclusion:

Pediatric residents perceive the importance of communication skills and competencies as crucial components in their training. A proper comprehensive communication skills training should be incorporated into the pediatric resident training curriculum.

Keywords: Communication skills, pediatrics, residents, Saudi Arabia

INTRODUCTION

International studies indicate that most health care facilities acknowledge the role of effective communication skills in establishing a good patient-doctor relationship.[1,2,3] In spite of several worldwide publications on guidelines that describe the need to acquire good communication skills and their impact on the outcome of overall management,[4,5] there are still a lot of variations in the use of this very important tool in health facilities throughout Saudi Arabia. Studies show that good communication and a better patient-doctor relationship correlate directly with improved quality of care.[6] In pediatrics, this communication is unique, as it involves both patients and their families. However, although most pediatric residents understand and acknowledge the importance of effective communication skills, they have much difficulty in using these skills confidently.[7] Communicating with children and their families sometimes is complex and influenced by the developmental and cognitive stage of the child, bashfulness of Saudi mothers, different sociocultural norms, and the little time the residents have to explain the situation. Training residents to acquire better skills can significantly increase their confidence in coping with difficult situations.[8] Effective rapport building not only alleviates the anxiety in the patients and their families but also improves the overall satisfaction level.[9] Parents value physicians who endeavor to understand their point of view, appreciate their concerns, communicate freely with them, and also have good clinical skills and knowledge.[10]

It is imperative that all our residents are well-acquainted with and have good communication skills to improve overall success of management. This can be achieved by various methods when residents are trained in a professional environment.[11]

The objective of the study was to determine pediatric residents' attitude toward patient-doctor communication skills and their perception of the significance of developing good patient-doctor communication skills, and to assess their level of confidence in using these skills.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional survey utilized a 47-item self-administered questionnaire to measure the pediatric residents' perception, attitudes, and confidence level regarding communication skills in their professional life during their residency and training program.

The sample included 297 pediatric residents enrolled in training programs in 13 different teaching hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Self-administered questionnaires were mailed to the program coordinators and directors for distribution to all trainee residents. The residents were asked to answer all questions and return the questionnaires to program coordinators and directors to be sent back to the principal investigator.

To examine residents' attitudes and perceptions of communication skills, a self-administered questionnaire developed by Harvard University was used after obtaining permission from the author.

The first part of the survey consisted of 14 items designed to evaluate the agreement of the participants that learning to communicate effectively with the patient was a priority. The second component of the questionnaire assessed the level of the resident physicians' understanding of the significance of developing their communications skills in the area of physician-patient relationship during their residency program. It also addressed how important they thought it was for the house staff to develop specific communication skills (importance scale) during their residency training and how confident they were about their own communication skills in each area (confidence scale). A five-point Likert scale was used to evaluate their responses. The Importance Scale contained 16 items, each ranging from 1 to 5 with a descriptive rating of “very low” to “very high.” The Confidence scale also had 16 items that ranged from 1 to 5 with a descriptive rating of “not confident” to “very confident.” The two scales asked the same questions consisting of 16 communications skills on the ability to discuss end-of-life issues with a patient and/or family, speak to children about serious illness, deliver bad news about illness to a patient and the family, deal with a “difficult” patient or parent, cultural awareness/sensitivity, understand psychosocial aspects of patient care and/or patients' perspective on their illness. The survey also included the demographic data of the residents such as program year, gender, and age and whether they had previously participated in a program to improve their communication skills with patients.

Statistical package for social science (SPSS) for Windows was used for data entry and analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all survey and demographic questions. Scale variables for all questions were evaluated for reliability using Cronbach's alpha.

RESULTS

The 297 pediatric residents enrolled in residency training programs in 13 different hospitals in Saudi Arabia participated in the survey. The response rate was 60% (n = 495): 49.5% were females. Of the residents, 34.4% were in their 1st year residency and 23.6% in the 2nd year, and were together considered as junior level residents; 25.1% were in the 3rd year and 17% in the 4th year of the residency program were also considered as junior level residents. There were 37.7% of mostly senior residents, 80% of whom had previously participated in a program to improve their communication skills with patients. A five-point Likert scale was used to assess the importance and confidence scales. Cronbach's alpha calculated for each scale was 0.940 and 0.921, respectively.

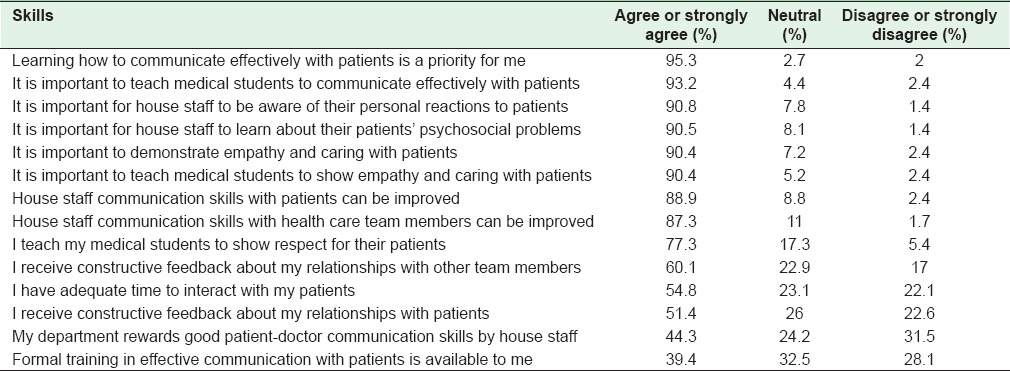

The majority (95.3%) of the residents in the study responded with either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” in learning how to communicate effectively with their patients. It is important for medical students to be taught to communicate effectively with patients (93.2%). Most of them agreed that it was important for house staff to be aware of their personal reactions to patients (90.8%) and to learn about their patients' psychosocial problems (90.5%). Similarly, they also realized that it is both important to demonstrate empathy and care (90.4%), and teach medical students to show empathy and care to patients (90.4%). About 88.9% of them agreed that the communication skills of house staff with the patients could be improved.

There was no significant difference between males and females with regard to their attitude toward the communication skills. However, a higher percentage of senior level residents (85%) compared to junior level residents (65%) believed that it was important. Next in importance was for house staff to learn about their patients' psychosocial problems (88.7%), followed by the understanding psychosocial aspects of patient care (88.6%). These were considered high or very high.

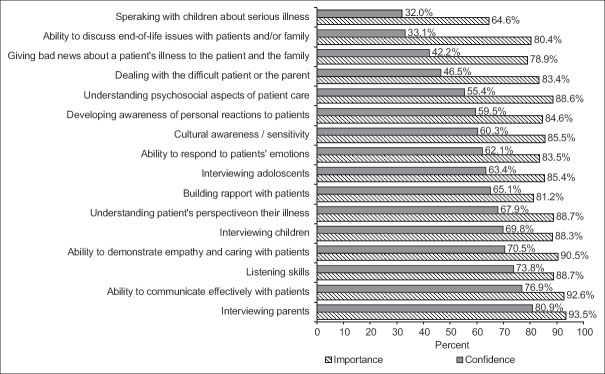

On the 16 communication skills studied, 80.9% of residents rated their confidence for interviewing or interacting with the parents of their patients as either “rather confident” or “very confident” followed by the ability to communicate effectively with patients (76.9%) and listening skills (73.8%). Seventy point 5% of residents indicated their ability to demonstrate empathy and care with patients and interview children, while 69.8% at the senior level rated their skills as confident. On the 16 communication skills included in the questionnaire, 60% or more of the house staff rated their confidence for ten of the skills as rather or very confident [Figure 1]. Statistically, there was no significant difference between the males and females in general. However, the senior level residents considered their confidence in communication skills significantly higher than their junior level colleagues (P = 0.04) with no gender differences at the senior level.

Figure 1.

Residents’ rating of self confidence in various communication skills and importance of communication skills

Sixty percent or fewer agreed or strongly agreed that various system supports related to communication skills were available in their training program. Half of them agreed or strongly agreed that they had adequate time to interact and receive constructive feedback on their relationship with their patients [Table 1]. About 40% agreed that formal training in effective communications with patients was available to them. There was no significant difference between the levels or genders.

Table 1.

Perception of training residents and their attitude toward communication skills

DISCUSSION

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in the USA requires residency programs to teach and assess interpersonal and communication competencies.[7] We could not find any national or international literature listed in PubMed reporting country-wise pediatric residents' assessment of their communication skills, so we tried to survey all the residency programs running at different hospitals in Saudi Arabia as regards the resident's perspectives of communication skills. We observed that there was a very strong agreement among the pediatric residents with learning to communicate effectively with their patients and the significance of teaching communication skills to medical students. Around 90% of the residents also saw the need for education in areas other than communication skills such as the awareness of their personal reactions to patients, psychosocial problems of their patients, and the demonstration of empathy and care to their patients. While the house staff clearly highlighted their understanding of the importance of learning communication skills, only one-third of them felt confident enough to speak with their pediatric or adolescent patients about serious illness and discuss the end-of-life issues with them or their families. Next came the breaking of bad news about a patient's illness to the patient and/or the family (42.2%). Developing the skill to deliver bad news to a patient or the family is necessary for quality care. Insensitivity on the part of the physician can lead to a lot of distress. Discussion of end-of-life issues with a patient or the family was considered very important (80.4%) by the residents, but only one-third were confident enough to handle this issue in a professional manner. This also highlights the need to improve the training of house staff in palliative care.

This study also highlights the need to make formal training in effective communication with patients available to the residents in their training program as this has been proved to help in improving the patient-physician relations outcomes.[12] Many different training programs are available that are based on different theories such as goals, plans, and action theories,[13] sociolinguistic theory,[14] and Leventhal's common-sense model.[15]

Only half of the residents reported receiving constructive feedbacks on their relationship with their patients, and less than a half of them said they had been rewarded by their departments on good patient-doctor communication skills.

The main limitation of the study was low response rate (60%). The questionnaire used was adapted from Harvard Medical School in Boston, USA. We did not have any means to measure the confounding effect of the cultural difference between the two countries.

CONCLUSION

The ability for members of the health care team to clearly and concisely communicate with the patient is a vital part of delivering quality care. The pediatric residents in our study showed a high level of confidence in basic communication skills such as interviewing parents, communicating with patients, and listening and demonstrating empathy and care, which is a core value of our culture in the Arabian Peninsula. However, when it came to more complex issues such as speaking about serious illnesses, discussion on end-of-life issues with the patients or their parents, and the delivery of bad news, the level of confidence was fairly low even though they realized their importance in medical practice. Based on the findings of this study, we stress the need for a continuous training program on the core and advanced communication skills as described in this study. Moreover, continued assessment of interpersonal skills should be part of the residency program and a requirement for the completion of the entire residency training program.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, Cole-Kelly K, Frankel R, Buffone N, et al. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: The Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79:495–507. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkman WB, Geraghty SR, Lanphear BP, Khoury JC, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Dewitt TG, et al. Effect of multisource feedback on resident communication skills and professionalism: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:44–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Zanten M, Boulet JR, McKinley DW, DeChamplain A, Jobe AC. Assessing the communication and interpersonal skills of graduates of international medical schools as part of the United States medical licensing exam (USMLE) step 2 clinical skills (CS) exam. Acad Med. 2007;82(10 Suppl):S65–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318141f40a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sans-Corrales M, Pujol-Ribera E, Gené-Badia J, Pasarín-Rua MI, Iglesias-Pérez B, Casajuana-Brunet J. Family medicine attributes related to satisfaction, health and costs. Fam Pract. 2006;23:308–16. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rider EA, Keefer CH. Communication skills competencies: Definitions and a teaching toolbox. Med Educ. 2006;40:624–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rider EA, Volkan K, Hafler JP. Pediatric residents' perceptions of communication competencies: Implications for teaching. Med Teach. 2008;30:e208–17. doi: 10.1080/01421590802208842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamiani G, Meyer EC, Leone D, Vegni E, Browning DM, Rider EA, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of an innovative approach to learning about difficult conversations in healthcare. Med Teach. 2011;33:e57–64. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.534207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shendurnikar N, Thakkar PA. Communication skills to ensure patient satisfaction. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:938–43. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0958-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson R, Barbara A, Feldman S. What patients want: A content analysis of key qualities that influence patient satisfaction. J Med Pract Manage. 2007;22:255–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sebiany AM. New trends in medical education. The clinical skills laboratories. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1043–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coyne JC, Racioppo MW. Never the Twain shall meet. Closing the gap between coping research and clinical intervention research? Am Psychol. 2000;55:655–64. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger CR. Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller K. Communication Theories: Perspectives, Processes, and Contexts. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donovan HS, Ward S. A representational approach to patient education. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33:211–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]