Abstract

Background and study aims

Preoperative biliary drainage is often initiated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in patients with potentially resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (PHC), but additional percutaneous transhepatic catheter (PTC) drainage is frequently required. This study aimed to develop and validate a prediction model to identify patients with a high risk of inadequate ERCP drainage.

Patients and Methods

Patients with potentially resectable PHC and preoperative (attempted) ERCP drainage were included from two specialty center cohorts between 2001 and 2013. Indications for additional PTC drainage were failure to place an endoscopic stent, failure to relieve jaundice, cholangitis, or insufficient drainage of the future liver remnant. A prediction model was derived from the European cohort and externally validated in the USA cohort.

Results

108 of 288 patients (38%) required additional preoperative PTC after inadequate ERCP drainage. Independent risk factors for additional PTC were proximal biliary obstruction on preoperative imaging (Bismuth 3 or 4) and pre-drainage total bilirubin level. The prediction model identified three subgroups: patients with a low risk of 7%, a moderate risk of 40%, and a high risk of 62%. The high-risk group consisted of patients with a total bilirubin level above 150 μmol/L and Bismuth 3a or 4 tumours, who typically require preoperative drainage of the angulated left bile ducts. The prediction model had good discrimination (AUC 0.74) and adequate calibration in the external validation cohort.

Conclusions

Selected patients with potentially resectable PHC have a high risk (62%) of inadequate preoperative ERCP drainage requiring additional PTC. These patients might do better with initial PTC instead of ERCP.

INTRODUCTION

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (PHC) is the most common type of cholangiocarcinoma with a median overall survival of 12 months if locally advanced or metastatic at presentation.[1] A combined extrahepatic bile duct and liver resection for resectable tumours has a median overall survival of 30 to 40 months in large series.[2-4] Unfortunately, surgical resection has been associated with a high rate of postoperative mortality (3-18%).[2-9] Liver failure is the most common cause of postoperative death, and has been attributed to extended liver resections in the setting of biliary obstruction and cholangitis.[10,11] Biliary drainage of the future liver remnant (FLR) is recommended by some to resolve biliary obstruction and improve liver function preoperatively.[12] Adequate drainage of the FLR, as reflected by normalized total bilirubin level and normal caliber biliary ducts, can potentially decrease postoperative morbidity, provided that the FLR volume is adequate. Two methods are used for biliary drainage: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and percutaneous transhepatic catheter (PTC) drainage.

The majority of patients referred to specialty centers for surgical treatment have already undergone (attempted) endoscopic drainage before referral.[13] However, ERCP for proximal biliary obstruction may not always offer adequate biliary drainage, and may contaminate undrained segments.[13,14] Many patients require additional PTC to obtain adequate preoperative biliary drainage or to treat infectious complications related to failed endoscopic stents. PTC has the advantage of offering selective drainage of the FLR, and can be useful in treating cholangitis with multiple isolated segments. In a previous report, out of 90 patients in whom biliary drainage for potentially resectable PHC was initiated with ERCP, 30 patients (33%) required additional preoperative PTC.[13]

Patients who have a high risk for additional preoperative PTC after inadequate initial ERCP may benefit from PTC drainage as the initial treatment. These patients could avoid the risks associated with ERCP including acute pancreatitis and contamination of undrained liver segments. The aim of this study was to develop and validate a prediction model to identify patients with a high risk of requiring additional preoperative PTC after initial ERCP drainage.

METHODS

Patients

Consecutive patients who underwent exploratory laparotomy with curative intent for presumed PHC between January 2001 and December 2013 were identified from prospectively maintained databases at two institutions: the Academic Medical Center (AMC) in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, USA. Criteria used in both centers to select patients for exploratory laparotomy and potential resection are detailed in Table 1. The institutional review board at both institutions approved this study; at MSKCC, compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was ensured.

Table 1.

Imaging criteria used in AMC and MSKCC to select patients for exploratory laparotomy and potential resection of PHC.

| Metastasis* | - No distant metastases (e.g., peritoneal, lung, or liver) |

| - No lymph node metastases beyond the hepatoduodenal ligament | |

|

| |

| Future liver remnant | Anticipated: |

| - Adequate volume (30-40%) | |

| - Tumor-free portal vein, after venous reconstruction if necessary | |

| - Tumor-free hepatic artery | |

| - Tumor free proximal and distal bile duct | |

Bilateral obstruction of 2nd order bile ducts (Bismuth 4) was not considered unresectable by itself.

Endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration or percutaneous biopsy may be used in selected patients to rule out metastases beyond the hepatoduodenal ligament.

All included patients had an obstruction of the common hepatic duct with or without obstruction of the bifurcation and 2nd order bile ducts that was suspicious for PHC. Patients with obstruction of the left or right hepatic duct alone without obstruction of the bifurcation were not included in this study, since these tumours normally do not cause jaundice and have no indication for preoperative stenting. All patients who underwent (attempted) ERCP with plastic stent placement as the initial biliary drainage procedure were included. Exclusion criteria were: no (attempted) preoperative drainage, endoscopic metal stents,[15,16] and a history of benign bile duct obstruction or cholecystitis with drainage procedures prior to suspicion of PHC. Patients who underwent PTC as initial drainage method were not included in the study cohort but were separately analysed.

Preoperative biliary drainage

Adequate preoperative biliary drainage requires decompression of bile ducts in the FLR with a total bilirubin level below 50 μmol/L (2.9 mg/dL). Hence, the left liver segments need to be drained in patients scheduled for right hepatectomy, and the right liver segments need to be drained in patients scheduled for left hepatectomy. Attempt at ERCP drainage was initiated in either a regional center before referral, or after referral to one of the two specialty centers. The initial ERCP drainage procedure most often resulted in placement of a single 10 Fr stent if technically successful. At presentation in the specialty centers, all patients with a suspicion of PHC were staged with CT and/or MRI and evaluated in a multidisciplinary team meeting.[17] Preoperative biliary drainage or additional biliary drainage was considered if cholestasis was present in the FLR as evidenced by elevated total bilirubin level and/or dilated bile ducts in the FLR, or if there were signs of cholangitis not responding to antibiotic treatment. When additional drainage was indicated, at AMC, the optimal method (repeat ERCP or PTC) for the additional drainage procedure was selected during a multidisciplinary team meeting, based on the cause of drainage failure and the biliary anatomy.[16] In some patients, repeat ERCP was used to obtain adequate drainage and PTC was not required. In others, repeat ERCP was not considered technically feasible and additional PTC was used. At MSKCC, PTC was used in all patients who required additional biliary drainage before exploratory laparotomy. At both centers the decision to proceed with additional PTC was ultimately at the discretion of the attending surgeon. Techniques of ERCP and PTC drainage have been described previously.[13]

Definitions

The endpoint in the prediction model was the indication for additional PTC after initial (attempted) ERCP drainage. Indications for additional PTC were classified as one of the following: technical failure of ERCP drainage defined as the inability to insert a draining stent; therapeutic failure of endoscopic stents, defined as persistent jaundice or recurrent jaundice prior to surgery; cholangitis after ERCP not responding to antibiotic treatment, characterized by fever, leukocytosis and total bilirubin; insufficient drainage of the FLR, characterized by persistent dilatation of the FLR bile ducts. The latter indication occurred when an endoscopic stent was placed in the contralateral bile ducts, and relieved jaundice without draining the bile ducts in the FLR, maintaining the increased risk of postoperative liver failure from obstruction in the FLR despite a normalized bilirubin level.[6] Study variables were restricted to data that was available before biliary drainage was initiated. These variables include demographics, comorbidities (Charlson comorbidity score),[18] hospital type of initial procedure (specialty versus regional center), pre-drainage total bilirubin level, and proximal extent of bile duct obstruction on imaging according to the Bismuth criteria.[19,20] The available preoperative images were retrospectively reviewed when the level of bile duct obstruction was missing in the original radiology reports (CN in AMC and BG in MSKCC).

Statistical analysis

The study variable pre-drainage total bilirubin level had 11% missing values (n=17) in the AMC cohort and 19% (n=25) in the MSKCC cohort. These values were missing when the referring center had not included lab values in the referral letter, and were therefore considered missing at random. Missing pre-drainage total bilirubin values were imputed with multiple imputation in both the derivation and validation cohort (5 imputation cohorts).[21] A regression model was used with all study variables as well as the available preoperative bilirubin levels. The data was pooled using Rubin’s rule.[22]

Univariable and multivariable analysis were based on the AMC cohort, which led to the development of a prediction model. Study variables were dichotomized around a cut-off, as determined by optimal sensitivity and specificity in the derivation dataset,[23] to allow clinical interpretation. In univariable analysis, associations were analysed using Fisher’s exact test, Pearson Chi-square or Mann-Whitney U as applicable. All study variables were entered in a multivariable logistic regression model, and evaluated using automated conditional backward selection with a cut-off value of P=0.1 to be retained in the regression model. Risk groups that were identified by the multivariable analysis were then collapsed into three groups (i.e. high, moderate, and low risk) using nearest neighbor clustering.[24] Logistic regression with the new grouping variable as a single predictor was used to determine the corresponding predicted outcomes. The resultant prediction model is presented as a table with predictions. This model was subsequently validated in the external MSKCC cohort. We assessed the prediction model in terms of discrimination (area under the curve [AUC]), and calibration.[25]

Subsequently, the total number of drainage procedures was analysed in patients who underwent PTC, with and without previous ERCP, using univariable analysis as described above. This comparison aimed to assess the potential gain if patients had been treated with initial PTC instead of initial ERCP, as proposed in the prediction model. All analyses were performed in SPSS v22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and R (a language and environment for statistical computing), version 3.0.2.

RESULTS

Study cohort

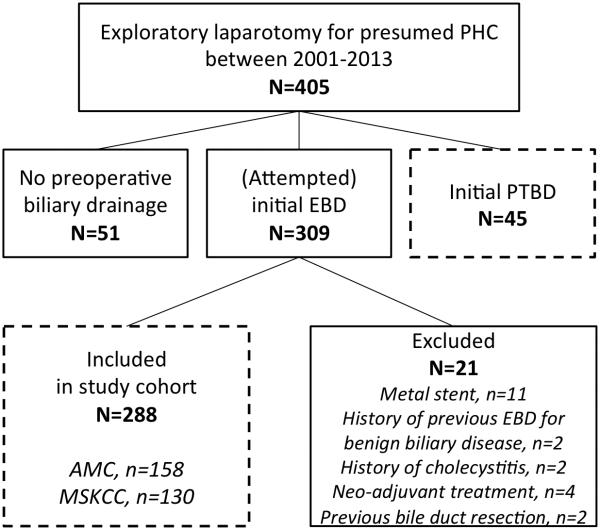

405 patients who underwent exploratory laparotomy with curative intent for presumed PHC were identified from the two databases. Patients without preoperative biliary drainage (n=51) were excluded, and patients with initial PTC (n=45) were analysed separately. Preoperative biliary drainage was initiated with (attempted) ERCP in the other 309 patients (76%). An additional 21 patients were excluded, of which 11 for metal stent placement, resulting in 288 patients for the final study cohort (158 from AMC in the derivation cohort and 130 from MSKCC in the validation cohort). Figure 1 details the inclusions and exclusions in a flowchart.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of in- and exclusions in the study. Boxes with dashed lines contain patients included in the study. Patients with initial (attempted) ERCP drainage meeting secondary exclusion criteria were included in the study cohort for the prediction model. Patients with initial PTC drainage were analyzed separately.

In the study cohort, final pathology after surgery confirmed the diagnosis of PHC in 273 of the 288 patients (95%) and 15 patients (5%) had benign disease. Among patients with PHC, 122 (45%) underwent bile duct resection combined with a liver resection and 25 (9%) underwent a bile duct resection only; 126 patients (46%) underwent no resection due to an intraoperative diagnosis of locally advanced or distant-metastatic disease. Postoperative 90-day mortality after resection of PHC was 14% (21 out of 147 patients), and median overall survival after resection of PHC was 37 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 25-49 months). Surgical and survival outcomes in groups with ERCP alone and additional PTC are detailed in Table e1 and Figure e1.

Preoperative biliary drainage procedures

The median number of preoperative ERCP drainage procedures in the prediction model cohort was 1 (range, 1-5), although 121 patients (42%) underwent 2 or more ERCP procedures. ERCP drainage was adequate in 180 patients (62.5%), but ultimately 108 of the 288 patients (37.5%) required additional PTC after initial ERCP. Therapeutic failure of endoscopic stents was the most common indication for additional PTC (n=42; 15%), followed by cholangitis after ERCP (n=31; 11%), technical failure of endoscopic stenting (n=18; 7%), and insufficient drainage of the FLR (n=17; 6%). A single PTC procedure was sufficient in 35 of these patients (32%), but the median number of additional PTC procedures was 2 (range, 1-6), and 35 patients (32%) required 3 or more PTC procedures. Patient characteristics and biliary drainage details from the two separate cohorts (AMC and MSKCC) are presented in Table 2. Indications for additional PTC in each center are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the two study cohorts.

| Variable | AMC (n=158) |

MSKCC (n=130) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at laparotomy, yrs | 64 (13) | 68 (17) |

| Male | 114 (58%) | 83 (42%) |

| Median BMI, kg/m2 | 25 (5) | 27 (6) |

| Median Charlson comorbidity score | 0 (1) | 0 (1) |

| Extent of bile duct obstruction | ||

| Bismuth 1/2 | 29 (18%) | 42 (32%) |

| Bismuth 3b – left 2nd order bile ducts | 39 (25%) | 20 (15%) |

| Bismuth 3a – right 2nd order bile ducts | 60 (38%) | 37 (29%) |

| Bismuth 4 – bilateral 2nd order bile ducts | 30 (19%) | 31 (24%) |

| Median pre-drainage total bilirubin, μmol/L * | 166 (172) | 152 (186) |

| (Attempted) ERCP drainage in regional hospital before referral |

114 (72%) | 128 (98%) |

| Median no. of ERCP drainage procedures | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Median time between 1st ERCP procedure and laparotomy, days |

87 (54) | 46 (31) |

| Additional PTC after initial ERCP drainage | 65 (41%) | 43 (33%) |

| Median no. of PTC procedures if any | 2 (2) | 2 (1) |

Categorical data are presented as no. (%). Continuous data are shown as the median (interquartile range).

To convert total bilirubin level to mg/dL, divide by 17.1.

Table 3.

Indications for additional PTC in the two study cohorts.

| Indication | AMC (n=158) |

MSKCC (n=130) |

|---|---|---|

| ERCP drainage technical failure | 6 (4%) | 12 (9%) |

| ERCP drainage therapeutic failure | 27 (17%) | 15 (12%) |

| Cholangitis | 21 (13%) | 10 (8%) |

| Insufficient drainage of the FLR | 11 (7%) | 6 (5%) |

| Total number of patients requiring additional PTC drainage | 65 (41%) | 43 (33%) |

Indications are presented as No. (%). FLR, future liver remnant.

Multivariable analysis

Demographics, comorbidities, and the hospital type of initial ERCP procedure (specialty versus regional referring center), were not associated with the indication for additional PTC after initial ERCP. The pre-drainage bilirubin level showed predictive value, after determining a cut-off of 150 μmol/L (sensitivity 0.69, 95% CI 0.56-0.80; specificity 0.55, 95% CI 0.44-0.66). Multivariable analysis in the AMC cohort showed that a pre-drainage total bilirubin level above 150 μmol/L (8.8 mg/dL) and the proximal extent of bile duct obstruction were independent predictors. (Table 4) Eight risk groups (2×4) were identified based on these predictors.

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of risk factors for additional PTC drainage in the AMC derivation study cohort.

| Variable | Total patients, n |

Additional PTC, n (%) |

Univariable

P-value |

Multivariable

P-value |

Odds ratio (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables selected | |||||

| Pre-drainage total bilirubin ≥150 μmol/L (8.8 mg/dL) | 0.02 | ||||

| No | 67 | 21 (31%) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 91 | 44 (48%) | 0.02 | 2.4 (1.2-5.0) | |

| Extent of bile duct obstruction | <0.001 | ||||

| Bismuth 1/2 | 29 | 2 (7%) | Reference | ||

| Bismuth 3b – left 2nd order bile ducts | 39 | 16 (41%) | 0.004 | 10.3 (2.1-50.4) | |

| Bismuth 3a – right 2nd order bile ducts | 60 | 30 (50%) | 0.001 | 14.9 (3.2-69.6) | |

| Bismuth 4 – bilateral 2nd order bile ducts | 30 | 17 (57%) | <0.001 | 18.8 (3.7-95.7) | |

| Variables not selected | |||||

| Male gender | 114 | 50 (44%) | 0.47 | ||

| Age ≥65 years | 75 | 26 (35%) | 0.15 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index ≥2 | 29 | 9 (31%) | 0.30 | ||

| (Attempted) ERCP drainage in regional hospital | 114 | 48 (42%) | 1.00 |

Data are presented as no. (%).

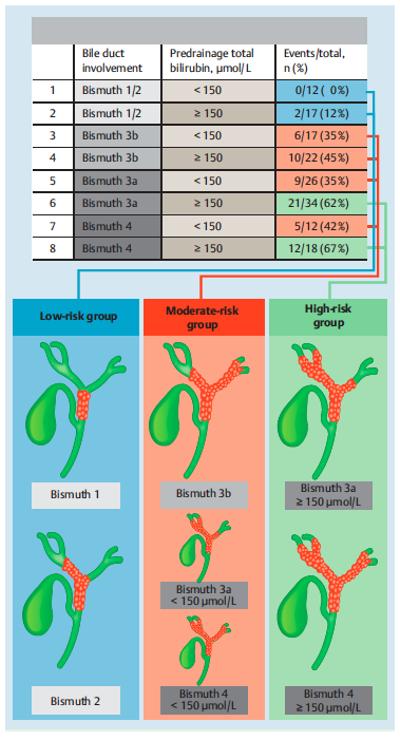

Model derivation

The 8 risk groups were collapsed into three risk groups based on the observed incidence of additional PTC in the AMC cohort. (Figure 2) The low-risk group (n=29) consisted of patients without 2nd order bile duct obstruction (Bismuth 1 or 2). The moderate-risk group (n=77) consisted of patients with left-sided 2nd order bile duct obstruction (Bismuth 3b) regardless of the pre-drainage total bilirubin level, and patients with right or bilateral 2nd order bile duct obstruction (Bismuth 3a or 4) in combination with a pre-drainage total bilirubin level below 150 μmol/L (8.8 mg/dL). The high-risk group (n=52) consisted of patients with right or bilateral 2nd order bile duct obstruction (Bismuth 3a or 4) and a pre-drainage total bilirubin level above 150 μmol/L (8.8 mg/dL). The corresponding predicted risks were 7% for the low-risk group, 40% for the moderate-risk group, and 62% for the high-risk group.

Figure 2.

Detailed and schematic presentation of the prediction model. Eight groups were identified from multivariable analysis. These groups were collapsed into three risk groups (i.e. low, moderate or high risk) based on the observed event rate of additional PTC drainage in the derivation cohort. Illustrations on the right side of the figure schematically show how patients are categorized into the three risk groups.

Model validation

The prediction model showed good discrimination in the AMC derivation cohort (AUC 0.72; 95% CI 0.63-0.80), as well as in the MSKCC validation cohort (AUC 0.74; 95% CI 0.64-0.83). Table 5 shows adequate calibration of the prediction model. Patients in the high-risk group required additional preoperative PTC in 62% of patients in the MSKCC validation cohort, which was identical to the predicted risk.

Table 5.

Calibration table showing the predicted risks and observed event rates of additional PTC drainage after inadequate ERCP drainage in the MSKCC validation cohort.

| Risk group | Predicted risk | Observed events in MSKCC, n/total n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Low risk | 7% (0-42) | 6/42 (14%) |

| Moderate risk | 40% (23-57) | 13/49 (27%) |

| High risk | 62% (45-79) | 24/39 (62%) |

Predicted risks are shown as percentages (95% confidence interval). Low risk: patients with Bismuth 1 or 2 tumours. Moderate risk: patients with Bismuth 3b tumours, and patients with Bismuth 3a or 4 in combination with a pre-drainage total bilirubin level below 150 μmol/L (8.8 mg/dL). High risk: patients with Bismuth 3a or 4 and a pre-drainage total bilirubin level above 150 μmol/L.

Patients with initial PTC

The number of drainage procedures was compared between the group of 108 patients who underwent additional PTC after inadequate ERCP drainage and the group of 45 patients that underwent initial PTC without previous ERCP. Both groups were comparable in terms of the predictive factors identified in this study, as shown in Table 6. The median total number of preoperative drainage procedures was significantly lower in those patients that were treated with initial PTC (2 versus 4, respectively; P <0.001).

Table 6.

Numbers of drainage procedures in patients who underwent additional PTC drainage and patients who underwent initial PTC drainage.

| Variable | Additional PTC after initial ERCP (n=108) |

Initial PTC (n=45) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive factors in the prediction model | |||

| Extent of bile duct obstruction | 0.73 | ||

| Bismuth 1/2 | 9 (8%) | 5 (11%) | |

| Bismuth 3b – left 2nd order bile ducts | 22 (20%) | 12 (27%) | |

| Bismuth 3a – right 2nd order bile ducts | 44 (41%) | 15 (33%) | |

| Bismuth 4 – bilateral 2nd order bile ducts | 33 (31%) | 13 (29%) | |

| Median pre-drainage total bilirubin, μmol/L* | 193 (160) | 190 (138) | 0.66 |

| Preoperative biliary drainage procedures | |||

| Median no. of ERCP procedures prior to PTC | 1 (1) | n/a | |

| Median no. of PTC procedures | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0.64 |

| Median total preoperative biliary drainage procedures |

4 (2) | 2 (2) | <0.001 |

Categorical data are presented as no. (%). Continuous data are shown as the median (interquartile range).

To convert total bilirubin level to mg/dL, divide by 17.1.

DISCUSSION

Preoperative biliary drainage potentially creates a safer environment in jaundiced patients prior to liver surgery for PHC; it improves function and regeneration in the future liver remnant.[12] The choice to use drainage and the method of drainage should be tailored to the anticipated resection, following careful examination of CT and/or MRI images.[16] Not all patients benefit from preoperative drainage, e.g. patients scheduled for pancreatectomy or local bile duct resection,[26] but it has been shown to reduce perioperative morbidity in patients selected for large liver resections for PHC.[6,7]

This study set out to predict inadequate preoperative ERCP drainage requiring additional PTC in patients with potentially resectable PHC. Two predictors were identified: the proximal extent of bile duct obstruction and the pre-drainage total bilirubin level. These factors were used to design a prediction model with three risk groups that was derived from the AMC cohort in Europe. The risk groups varied in the predicted risk of additional PTC after initial ERCP: low (7%), intermediate (40%), and high (62%) risk. The high-risk subgroup consists of patients with both a high pre-drainage bilirubin level (≥150 μmol/L or 8.8 mg/dL) and right-sided or bilateral 2nd order bile duct obstruction (Bismuth type 3a or 4). External validation in the MSKCC cohort in the United States showed good discriminative power and adequate calibration.

This prediction model can be applied as a clinical decision rule for patients with potentially resectable PHC. An initial ERCP appears futile or even harmful in patients with a high risk (62%) of requiring additional preoperative PTC; the use of ERCP drainage in patients with an intermediate risk (40%) of requiring additional PTC may be subject to debate; the use of ERCP drainage in patients with a low risk (7%) of requiring additional PTC seems justified.

A median total of four preoperative drainage procedures were observed in patients who required additional PTC after inadequate ERCP drainage. In comparison, we analysed the number of drainage procedures in a comparable group of 45 patients who underwent initial PTC without previous ERCP, and showed that these patients underwent significantly fewer drainage procedures. Reducing the number of preoperative biliary drainage procedures in patients with PHC is important because every biliary drainage procedure has associated procedural risks (e.g., acute pancreatitis) and may cause patient discomfort.[13] Moreover, biliary drainage, and in particular inadequate biliary drainage can cause cholangitis, which is the most important risk factor for postoperative mortality after major liver resections for PHC.[5,11]

The total bilirubin level reflects the extent and severity of obstruction in the bile ducts, and may represent a difficult stricture to drain endoscopically. The level of bile duct involvement predicts the need for additional preoperative PTC for several reasons. ERCP drainage is less technically demanding and has good outcome in patients with Bismuth 1 or 2 tumours, as previously shown by others.[27] Tumours with obstruction of 2nd order bile ducts (i.e. ≥Bismuth 3) are more difficult to manage endoscopically, but the anatomical relation between tumour and bile ducts is critical within this group. The left liver segments are more difficult to drain endoscopically than the right, because the angle of the left hepatic duct is sharper and more difficult to negotiate with the endoscopic guide wire. Therefore, preoperative PTC drainage is more required in patients with type 3a or 4 tumors, who often require right (extended) hepatectomy and preoperative drainage of the left liver segments, compared to patients with type 3b tumors, who require left hepatectomy and preoperative drainage of the right liver segments. In addition, Bismuth 3a and 4 tumours cause isolation of two large sections of the liver, the right anterior and posterior section, representing about two-thirds of the liver volume.[28] Therapeutic failure after ERCP drainage is common in these patients because a single stent only drains about a third of the liver, and there is a higher risk of contaminating obstructed biliary radicles and cholangitis. Corroboratively, type 3a and 4 tumours had the highest Odds ratios for requiring additional PTC in the statistical model, and were consequently grouped together as ‘high-risk’ by the automated clustering.

Endoscopic guidelines, including the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline published in this journal, recommend that endoscopic drainage of perihilar strictures should be performed in high-volume centers.[15,16] Although the hospital type of initial ERCP (regional versus specialty center) was not associated with failure or success of preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage in this study, it seems preferable to refer patients at an early stage. Multidisciplinary teams in specialty centers have wide experience in assessing resectability, evaluating the indication for biliary drainage, and choosing the optimal method of biliary drainage to be used. Moreover, both ERCP and PTC are readily available in most Western high-volume centers, whereas only few regional centers hold the expertise for PTC.

There are a number of strengths to this study. Although it has previously been shown that PTC is a better option compared to ERCP for palliative drainage of Bismuth 3 and 4 tumors, this is the first study providing a clinical decision rule for preoperative drainage in patients with potentially resectable PHC. Furthermore, the study setup of focusing on patients with ERCP stents reflects current practice, since most patients are currently being referred to specialty centers with an ERCP stent in situ. Many of these patients (38% in the present study) have inadequate drainage after ERCP, and could thus have benefited from initial PTC drainage. Derivation of the prediction model in a European center and subsequent validation in a US center also showed that the predictions are robust and surpass cultural differences in drainage policy that may exist between centers. Finally, this is the largest reported series of patients with biliary drainage for PHC (n=288), while it consists solely of patients who were selected for surgical therapy.

There are several limitations to this retrospective study. The cohorts included patients who underwent drainage in regional or specialty centers in two different continents, so some heterogeneity in procedural methods can be expected. Consequently, the results of this study may not translate to specialized endoscopists with vast experience in drainage of PHC. Secondly, as the model was optimized for prediction, care must be taken when interpreting the presented Odds ratios for understanding of etiologic risk factors, since they were not adjusted for all potential confounders. Thirdly, selection of predictors in the model was based on backward regression, even though more sophisticated methods have recently been developed, e.g. model selection with the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO).[29] Nonetheless, discrimination and calibration were both good in the external validation dataset, which we took as evidence that the derived prediction model was accurate. Fourthly, we used multiple imputation of the missing pre-drainage total bilirubin levels in both the derivation and validation cohort.[21] Although imputation may have introduced a small bias, imputation of missing variables has been shown to decrease the risk of bias by not excluding patients with missing values.[30] Fifthly, this study included 288 patients who underwent exploratory laparotomy after initial endoscopic drainage, but the intended resection was not performed in a large subset of patients (46%) due to an intraoperative diagnosis of locally advanced or distant metastatic disease. Unfortunately, a finding of inoperability at the time of surgery is common among patients with PHC, and improvements in preoperative staging are much needed for better patient selection. Lastly, this study could not evaluate whether PTC is associated with a lower rate of complications or better oncologic outcome than ERCP. Opinions on the preferred method of preoperative biliary drainage vary greatly, all based on retrospective data. ERCP is widely available, and is considered to be less invasive than PTC. Japanese institutions advocate ERCP drainage, and in particular endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, because percutaneous catheter tract metastases have been described in 2-5% after preoperative PTC and resection of PHC.[31-33] Other centers prefer to use preoperative PTC.[3,4] Percutaneous drainage has the ability to selectively drain liver segments, and percutaneous catheters may reduce hepaticojejunostomy leaks postoperatively. Moreover, preoperative PTC has been associated with lower rates of cholangitis in small series.[13,14] A clinical trial is currently being conducted to assess such differences.[34]

In conclusion, we derived and validated a prediction model that identifies patients with potentially resectable PHC who likely require preoperative PTC after inadequate drainage with ERCP alone. Patients with obstruction of the right or bilateral 2nd order bile ducts (Bismuth 3a or 4), and a total bilirubin level above 150 μmol/L (8.8 mg/dL), have a high risk (62%) of requiring additional preoperative PTC after initial ERCP drainage. These patients should therefore be considered for initial PTC rather than endoscopic drainage, to minimize the total number of drainage procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding:

JW received a grant from the Academic Medical Center Young Talent Fund, and BG received a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

For the remaining authors none were declared.

This study has been presented at the United European Gastroenterology Week in Vienna, October 18-22, 2014.

REFERENCES

- 1.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebata T, Kosuge T, Hirano S, et al. Proposal to modify the International Union Against Cancer staging system for perihilar cholangiocarcinomas. Br J Surg. 2014;101:79–88. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuo K, Rocha FG, Ito K, et al. The Blumgart preoperative staging system for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of resectability and outcomes in 380 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Ardito F, et al. Improvement in perioperative and long-term outcome after surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: results of an Italian multicenter analysis of 440 patients. Arch Surg. 2012;147:26–34. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagino M, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, et al. Evolution of surgical treatment for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a single-center 34-year review of 574 consecutive resections. Ann Surg. 2013;258:129–140. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182708b57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy TJ, Yopp A, Qin Y, et al. Role of preoperative biliary drainage of liver remnant prior to extended liver resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:445–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farges O, Regimbeau JM, Fuks D, et al. Multicentre European study of preoperative biliary drainage for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2013;100:274–283. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuhaus P, Thelen A, Jonas S, et al. Oncological superiority of hilar en bloc resection for the treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1602–1608. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser GM, Paul A, Sgourakis G, et al. Novel prognostic scoring system after surgery for Klatskin tumor. Am Surg. 2013;79:90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagino M, Kamiya J, Uesaka K, et al. Complications of hepatectomy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2001;25:1277–1283. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakata J, Shirai Y, Tsuchiya Y, et al. Preoperative cholangitis independently increases in-hospital mortality after combined major hepatic and bile duct resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:1065–1072. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0464-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iacono C, Ruzzenente A, Campagnaro T, et al. Role of preoperative biliary drainage in jaundiced patients who are candidates for pancreatoduodenectomy or hepatic resection: highlights and drawbacks. Ann Surg. 2013;257:191–204. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826f4b0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kloek JJ, van der Gaag NA, Aziz Y, et al. Endoscopic and percutaneous preoperative biliary drainage in patients with suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Onodera M, et al. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage is the most suitable preoperative biliary drainage method in the management of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:242–248. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan SA, Davidson BR, Goldin RD, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: an update. Gut. 2012;61:1657–1669. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumonceau J-M, Tringali A, Blero D, et al. Biliary stenting: indications, choice of stents and results: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline. Endoscopy. 2012;44:277–298. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Gulik TM, Kloek JJ, Ruys AT, et al. Multidisciplinary management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumor): extended resection is associated with improved survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:170–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bismuth H, Nakache R, Diamond T. Management strategies in resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:31–38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199201000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vergouwe Y, Royston P, Moons KGM, et al. Development and validation of a prediction model with missing predictor data: a practical approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Budczies J, Klauschen F, Sinn BV, et al. Cutoff Finder: a comprehensive and straightforward Web application enabling rapid biomarker cutoff optimization. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cover T, Hart P. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. Information Theory, IEEE Transactions on 1967. 13:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steyerberg ES. Clinical prediction models. Springer; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Gaag NA, Rauws EA, van Eijck CH, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:129–137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paik WH, Park YS, Hwang JH, et al. Palliative treatment with self-expandable metallic stents in patients with advanced type III or IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a percutaneous versus endoscopic approach. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2009;69:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vienne A, Hobeika E, Gouya H, et al. Prediction of drainage effectiveness during endoscopic stenting of malignant hilar strictures: the role of liver volume assessment. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2010;72:728–735. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, et al. Springer Series in Statistics. Springer-Verlag New York; New York, NY: 2009. The Elements of Statistical Learning Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen KJM, Donders ART, Harrell FE, et al. Missing covariate data in medical research: to impute is better than to ignore. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawashima H, Itoh A, Ohno E, et al. Preoperative endoscopic nasobiliary drainage in 164 consecutive patients with suspected perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a retrospective study of efficacy and risk factors related to complications. Ann Surg. 2013;257:121–127. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318262b2e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang S, Song G-W, Ha T-Y, et al. Reappraisal of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage tract recurrence after resection of perihilar bile duct cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36:379–385. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi Y, Nagino M, Nishio H, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage catheter tract recurrence in cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1860–1866. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiggers JK, Coelen RJS, Rauws EA, et al. Preoperative endoscopic versus percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in potentially resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (DRAINAGE trial): design and rationale of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterology. 2015;15:20. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0251-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.