Abstract

Background

Female sex hormones are known to have immunomodulatory effects. Therefore, reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use could influence the risk of multiple myeloma in women. However, the role of hormonal factors in multiple myeloma etiology remains unclear because previous investigations were underpowered to detect modest associations.

Methods

We conducted a pooled analysis of seven case–control studies included in the International Multiple Myeloma Consortium, with individual data on reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use from 1,072 female cases and 3,541 female controls. Study-specific odd ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using logistic regression and pooled analyses were conducted using random effects meta-analyses.

Results

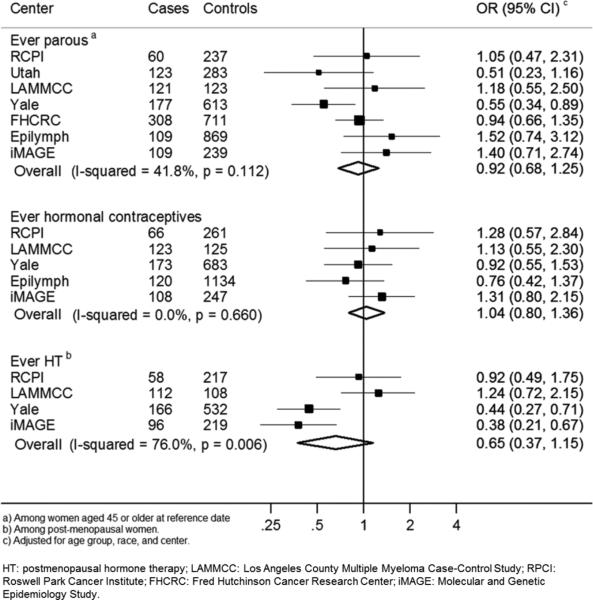

Multiple myeloma was not associated with reproductive factors, including ever parous (OR=0.92, 95%CI=0.68-1.25), or with hormonal contraception use (OR=1.04, 95%CI=0.80-1.36). Postmenopausal hormone therapy users had non-significantly reduced risks of multiple myeloma compared with never users, but this association differed across centers (OR=0.65, 95%CI=0.37-1.15, I2=76.0%, p-heterogeneity= 0.01).

Conclusions

These data do not support a role for reproductive factors or exogenous hormones in myelomagenesis.

Impact

Incidence rates of multiple myeloma are higher in men than in women, and sex hormones could influence this pattern. Associations with reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use were inconclusive despite our large sample size, suggesting that female sex hormones may not play a significant role in multiple myeloma etiology.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignancy characterized by the accumulation of clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow, abnormal secretion of monoclonal protein and end organ damage (1). Incidence rates are higher in men than in women (2). Because female sex hormones have immunomodulatory effects, reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use may affect risk for MM. However, the role of hormonal factors in MM etiology remains unclear. A few studies addressed possible associations between MM risk and reproductive factors, such as parity (3–6) or use of postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT) (6–8), but yielded inconsistent results as most studies were underpowered. We conducted a pooled analysis of case–control studies included in the International Multiple Myeloma Consortium (IMMC) to clarify the role of hormonal factors in the etiology of MM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We pooled individual-level questionnaire data from the seven IMMC case-control studies that collected information on reproductive factors among women (1,072 cases and 3,541 controls). These studies were: Los Angeles County Multiple Myeloma Case-Control Study (LAMMCC), Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI), Utah, Epilymph, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) 1980s, National Cancer Institute (NCI)-Yale, and Molecular and Genetic Epidemiology Study (iMAGE). Enrollment period, age eligibility, study design, sample sizes, and participation rates within each study are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. Parity was defined as number of live-births in NCI-Yale, iMAGE, and RCPI, and as number of children in all other studies.

Within each study, we computed odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) using unconditional logistic regression, adjusting for age group (four categories), race (except for Epilymph, which did not collect these data), and study center (for multicentric studies: Epilymph and FHCRC 1980s). Random-effects models were used to calculate pooled estimates using the DerSimonian & Laird method. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the I2 statistic and p-heterogeneity using the Mantel-Haenszel method. Analyses on parity and gravidity were restricted to women aged 45 or older, as they are likely to have completed their reproductive history. Analyses on HT were restricted to postmenopausal women, defined as women who reported cessation of their menstrual periods. Wald tests were utilized to assess heterogeneity between strata.

RESULTS

In this pooled analysis, we did not observe any statistically significant association between MM and age at menarche or at menopause, ever pregnant, number of pregnancies, ever parous, number of children, age at first birth, or cause of menopause (Table 1). The association between MM and ever use of hormonal contraceptives was not significant (OR=1.04, 95%CI=0.80-1.36; Table 1). Similarly, we saw no significant associations or consistent patterns for age and year at first use, duration, or time since last hormonal contraceptive use.

Table 1.

Associations between reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use and multiple myeloma risk.

| Co | Ca | Pooled OR (95%CI)* | I2 | P-het | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REPRODUCTIVE FACTORS | |||||

| Age at menarchea | |||||

| Total | 1335 | 482 | No. centers=4 | ||

| <11 | 256 | 86 | Ref | ||

| 12-13 | 717 | 271 | 1.20 (0.89, 1.63) | 0.0% | 0.58 |

| >14 | 362 | 125 | 1.03 (0.73, 1.45) | 0.0% | 0.57 |

| Ever pregnantc | |||||

| Total | 2321 | 691 | No. centers=6 | ||

| No | 228 | 69 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2093 | 622 | 0.90 (0.57, 1.44) | 48.2% | 0.09 |

| No of pregnanciesb | |||||

| Total | 1494 | 593 | No. centers=5 | ||

| None | 142 | 64 | Ref | ||

| 1 | 145 | 52 | 0.80 (0.39, 1.64) | 55.2% | 0.06 |

| 2 | 329 | 134 | 0.83 (0.57, 1.20) | 0.0% | 0.78 |

| 3 | 296 | 118 | 0.90 (0.50, 1.60) | 51.8% | 0.08 |

| >4 | 582 | 225 | 0.91 (0.54, 1.54) | 50.3% | 0.09 |

| Ever parousd | |||||

| Total | 3075 | 1007 | No. centers=7 | ||

| Never | 408 | 150 | Ref | ||

| Ever | 2667 | 857 | 0.92 (0.68, 1.25) | 41.8% | 0.11 |

| No. of childrend | |||||

| Total | 3075 | 1007 | No. centers=7 | ||

| None | 408 | 150 | Ref | ||

| 1 | 410 | 138 | 0.95 (0.66, 1.38) | 30.9% | 0.19 |

| 2 | 802 | 274 | 0.96 (0.75, 1.24) | 0.0% | 0.46 |

| 3 | 635 | 190 | 0.91 (0.60, 1.37) | 53.1% | 0.05 |

| >4 | 820 | 255 | 0.91 (0.64, 1.30) | 41.3% | 0.12 |

| Age at first birthe | |||||

| Total | 1941 | 449 | No. centers=4 | ||

| Nulliparous | 255 | 64 | Ref | ||

| <20 | 237 | 66 | 0.97 (0.50, 1.89) | 54.4% | 0.09 |

| 20-<25 | 749 | 167 | 0.99 (0.58, 1.70) | 56.1% | 0.08 |

| 25+ | 700 | 152 | 0.96 (0.59, 1.57) | 44.8% | 0.14 |

| Age at menopauseb | |||||

| Total | 1265 | 524 | No. centers=5 | ||

| <45 | 414 | 184 | Ref | ||

| 45-49 | 313 | 118 | 1.00 (0.74, 1.35) | 0.0% | 0.46 |

| >50 | 538 | 222 | 1.12 (0.86, 1.45) | 0.0% | 0.58 |

| Cause of menopausef | |||||

| Total | 800 | 397 | No. centers=4 | ||

| Natural | 433 | 197 | Ref | ||

| Surgical / Therapeutic | 367 | 200 | 1.11 (0.80, 1.54) | 36.7% | 0.19 |

| EXOGENOUS HORMONE USE | |||||

| Ever hormonal contraceptiong | |||||

| Total | 2450 | 590 | No. centers=5 | ||

| Never used | 1805 | 426 | Ref | ||

| Ever used | 645 | 164 | 1.04 (0.80, 1.36) | 0.0% | 0.66 |

| Age at first hormonal contraceptiong | |||||

| Total | 2434 | 587 | No. centers=5 | ||

| Never used | 1805 | 426 | Ref | ||

| <25 | 421 | 101 | 1.07 (0.76, 1.49) | 0.0% | 0.80 |

| >25 | 208 | 60 | 1.08 (0.76, 1.54) | 0.0% | 0.42 |

| Year at first hormonal contraceptiong | |||||

| Total | 2434 | 587 | No. centers=5 | ||

| Never used | 1805 | 426 | Ref | ||

| <1975 | 353 | 119 | 1.19 (0.87, 1.62) | 0.0% | 0.87 |

| ≥1975 | 276 | 42 | 1.18 (0.65, 2.14) | 19.6% | 0.29 |

| Time since last hormonal contraceptiong | |||||

| Total | 2421 | 588 | No. centers=5 | ||

| Never used | 1891 | 428 | Ref | ||

| <20 | 275 | 70 | 1.22 (0.84, 1.76) | 0.0% | 0.50 |

| >20 | 255 | 90 | 1.09 (0.75, 1.58) | 15.2% | 0.32 |

| Years of hormonal contraceptiong | |||||

| Total | 2415 | 582 | No. centers=5 | ||

| Never used | 1805 | 426 | Ref | ||

| <5 | 217 | 69 | 1.30 (0.92, 1.83) | 0.0% | 0.89 |

| >5 | 393 | 87 | 0.96 (0.57, 1.63) | 55.6% | 0.06 |

| Ever HTa | |||||

| Total | 1076 | 432 | No. centers=4 | ||

| Never used | 703 | 307 | Ref | ||

| Ever used | 373 | 125 | 0.65 (0.37, 1.15) | 76.0% | 0.01 |

| Age first used HTa | |||||

| Total | 1057 | 425 | No. centers=4 | ||

| Never used | 703 | 307 | Ref | ||

| <50 | 197 | 72 | 0.60 (0.31, 1.17) | 71.5% | 0.01 |

| >50 | 157 | 46 | 0.61 (0.41, 0.90) | 4.5% | 0.37 |

| Year first used HTa | |||||

| Total | 1057 | 425 | No. centers=4 | ||

| Never used | 703 | 307 | Ref | ||

| <1980 | 143 | 54 | 0.58 (0.33, 1.04) | 38.9% | 0.18 |

| ≥1980 | 211 | 64 | 0.81 (0.37, 1.77) | 75.3% | 0.01 |

| Time since last HT consumptiona | |||||

| Total | 1055 | 424 | No. centers=4 | ||

| Never used | 703 | 307 | Ref | ||

| Current | 150 | 41 | 0.84 (0.30, 2.38) | 77.1% | <0.01 |

| <10 | 116 | 46 | 0.90 (0.37, 2.16) | 76.5% | 0.01 |

| >10 | 86 | 30 | 0.52 (0.21, 1.26) | 57.9% | 0.07 |

| Years of HT usea | |||||

| Total | 1056 | 423 | No. centers=4 | ||

| Never used | 703 | 307 | Ref | ||

| <5 | 136 | 54 | 0.64 (0.30, 1.37) | 71.4% | 0.01 |

| >5 | 217 | 62 | 0.56 (0.33, 0.97) | 57.6% | 0.07 |

Adjusted for center, age (four categories), and race (white, black and others).

Co: controls Ca: cases, OR: Odds Ratio, CI: Confidence interval, P-het: p-value for heterogeneity, HT: postmenopausal hormone therapy.

Studies with data on periods starting, ever HT use, number of years HT was used, years since last HT consumption and age at first post-menopausal HT use were LAMMCC, RPCI, NCI-Yale and iMAGE. Analyses on HT variables were performed among postmenopausal women.

Analyses on periods stopping were performed among postmenopausal women. Analyses on number of pregnancies were performed among women aged 45 or older at reference date. Studies with data on periods stopping and number of pregnancies were LAMMCC, RPCI, NCI-Yale, iMAGE, and Utah.

Among women aged 45 or older at reference date. Studies with data on ever being pregnant were LAMMCC, RPCI, NCI-Yale, iMAGE, Utah and Epilymph.

Among women aged 45 or older at reference date. All studies collected data on parity and number of children.

Among women aged 45 or older at reference date. Studies with data on age at first child were RPCI, Epilymph, NCI-Yale and iMAGE.

Among postmenopausal women. Studies with data on cause of menopause were LAMMCC, RPCI, Utah and iMAGE.

Studies with data on hormonal contraception use, number of years hormonal contraception was used, years since last hormonal contraception consumption and age at first hormonal contraception use were LAMMCC, RPCI, Epilymph, NCI-Yale and iMAGE.

HT use showed non-significant decreased risks of MM (OR=0.65, 95%CI=0.37-1.15), but also showed significant heterogeneity between centers (I2= 76.0%, p=0.01, Figure 1). Further adjustment for BMI, education, tobacco, and alcohol yielded a similar risk estimate (OR=0.70, 95%CI=0.39-1.25). Inverse associations were observed among women taking HT at ages 50 or older, or for more than 5 years, compared with never use (OR=0.61, 95%CI=0.41-0.90; and OR=0.56, 95%CI=0.33-0.97, respectively), although heterogeneity between centers hampered interpretation (Supplemental Figure 1). Stratified analyses by cause of menopause, education, and BMI did not reveal statistically significant heterogeneity (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Study-specific risks of multiple myeloma for ever versus never parous, hormonal contraceptives and postmenopausal hormone therapy.

DISCUSSION

This large pooled analysis of 1,072 female cases and 3,541 controls yielded null associations between MM and reproductive factors. To our knowledge, 3 case-control studies (3–5,8) and 3 cohorts (4,6,7) have previously evaluated associations between reproductive factors, or exogenous hormone use and risk of MM. Inconsistent results were observed for parity and MM, with both significant inverse associations (5), increased risks (4), and null results (3,6). Previously reported associations for hormonal contraceptives and MM have been null (5,6). Significant inverse associations for HT use were observed in an Italian case-control study (8), but these associations were not corroborated in two cohort studies (6,7). However, conclusions in these studies have been limited by small sample sizes of women using HT.

Our study was based on a large dataset with individual-level information on reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use, yet we did not observe consistent patterns with these factors and MM risk. We had the ability to control for a variety of potential confounders, including education, BMI and alcohol use. Ignoring these variables may have biased previous studies of HT and cancer, due to the potential for selection bias and a healthy user effect. We did not observe clear evidence of confounding by those variables in the present analysis, although residual confounding cannot be discarded in explaining some of our results, in particular for HT. Also, use of controls that may not be representative of the population from which the cases arose was an inherent limitation of some of the participating studies’ design. In summary, our data do not support a significant role for reproductive factors or exogenous hormones in myelomagenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

The work conducted by L. Costas was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness - Carlos III Institute of Health (Río Hortega CM13/00232 and M-AES MV15/00025), and the University of Barcelona (Research Abroad Grant 2012). This work was partially supported by the public grants from Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness - Carlos III Institute of Health (PI11/01810, PI14/01219), and Catalan Government (2014SGR756). Epilymph was supported by European Commission 5th Framework Programme (QLK4-CT-2000-00422); 6th Framework Programme (FOOD-CT-2006-023103); Carlos III Institute of Health (FIS PI081555, RCESP C03/09, RTICESP C03/10, RTICRD06/0020/0095, CIBERESP and European Regional Development Fund-ERDF); Marató TV3 Foundation (051210); International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC-5111); MH CZ - DRO (MMCI, 00209805), RECAMO CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0101; Fondation de France (1999 008471; EpiLymph-France); Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC, Investigator Grant 11855); Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research, PRIN programme (2007WEJLZB, 20092ZELR2); and the German Federal Office for Radiation Protection (StSch4261 and StSch4420; Epilymph Germany). Funding for the Utah study was, in part, from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society 6067-09 (to N.J. Camp) and the NCI CA152336 (to N.J. Camp). Data collection for the Utah resource was made possible by the Utah Population Database (UPDB) and the Utah Cancer Registry (UCR). Partial support for all datasets within the UPDB was provided by the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) and the HCI Cancer Center Support grant, P30 CA42014 from the NCI. The UCR is funded by contract HHSN261201000026C from the NCI SEER program with additional support from the Utah State Department of Health and the University of Utah. The work conducted by B.M. Birmann was supported, in part, by grants from the NCI (K07 CA115687, R01 CA127435, R01 CA149445) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-11-020-01-CNE)The work conducted by E.E. Brown was supported, in part, grants from the NCI (U54CA118948, R21CA155951, R25CA76023, R01CA186646, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA13148) and the American Cancer Society (IRG60-001-47).The work conducted by S.S. Wang was supported, in part, by federal funds from the NCI, NIH, under R01CA036388, R01CA077398, and K05CA136967 and by the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA033572. The NCI-Yale Myeloma Study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos M-V, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e538–48. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith A, Roman E, Howell D, Jones R, Patmore R, Jack A, et al. The Haematological Malignancy Research Network (HMRN): a new information strategy for population based epidemiology and health service research. Br J Haematol. 2010;148:739–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavani A, Pregnolato A, Vecchia CL, Franceschi S. A case-control study of reproductive factors and risk of lymphomas and myelomas. Leuk Res. 1997;21:885–8. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(97)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang SS, Voutsinas J, Chang ET, Clarke CA, Lu Y, Ma H, et al. Anthropometric, behavioral, and female reproductive factors and risk of multiple myeloma: a pooled analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:1279–89. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0206-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costas L, Casabonne D, Benavente Y, Becker N, Boffetta P, Brennan P, et al. Reproductive factors and lymphoid neoplasms in Europe: findings from the EpiLymph case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:195–206. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9869-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morton LM, Wang SS, Richesson DA, Schatzkin A, Hollenbeck AR, Lacey JV. Reproductive factors, exogenous hormone use and risk of lymphoid neoplasms among women in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study Cohort. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2737–43. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teras LR, Patel AV, Hildebrand JS, Gapstur SM. Postmenopausal unopposed estrogen and estrogen plus progestin use and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study-II Cohort. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:720–5. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.722216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altieri A, Gallus S, Franceschi S, Fernandez E, Talamini R, La Vecchia C. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of lymphomas and myelomas. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2004;13:349–51. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000136573.16740.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.