Abstract

Vitamin D3 has been described to have different extraskeletal roles by acting as parahormone in obesity, diabetes, cancer, cognitive impairment, and dementia and to have important regulatory functions in innate immunity. There are no studies showing extraskeletal changes associated with hypovitaminosis D3 in eating disorders. Methods. We have analyzed the blood of 18 patients affected by anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa collected over a 15-month period. We performed a panel of chemical and clinical analyses: the assay of vitamin D3, the immunoblotting of vitamin D receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, and the genotyping of 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter linked polymorphic region. Results. We choose 18 patients with a normal blood test profile such as thyroid hormones, hepatic and renal parameters, triglycerides, proteins, vitamin B12, and folic acid. Among these emerged the case of a woman with long-term anorexia nervosa and the case of a woman with long-term bulimia nervosa both complicated by anxiety and depression, severe hypovitaminosis D3, decrease of vitamin D receptor, leukopenia, and 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter linked polymorphic region short allele. Conclusion. The results induce hypothesising that the severe hypovitaminosis D3 might be responsible for the lack of the inflammatory response and the depressive symptoms in patients with long-term eating disorders.

1. Introduction

The eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN), have been classically described with a clear female preponderance [1]. AN is a psychopathology characterized by the relentless drive for thinness and/or a morbid fear of fatness and BN is characterized by recurrent episodes of overeating in which large amounts of food are consumed in short periods [2]. Both are often accompanied by comorbid psychiatric disorders, that is, affective, anxiety, and personality disorders [2]. Eating disorders have multifactorial etiology, from endocrine abnormalities to genetic, psychological, and environment factors [3]. Individuals with AN and BN are consistently characterized by perfectionism, obsessive-compulsiveness, and dysphoric mood [4].

Vitamin D3 is recognized to have different extraskeletal roles by acting as parahormone. Recent evidence correlates serum vitamin D3 deficiency to obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular risks, cancer [5], cognitive impairment, and dementia [6]. The anti-inflammation activity of vitamin D3 has drawn more and more attention of researchers to investigate its role in regulating the progression of inflammatory diseases [7] as an important regulator of innate immunity [8]. Vitamin D3 deficiency has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease [9], chronic kidney disease [10], asthma, and atopy [11]. Until now vitamin D3 deficiency in patients with eating disorders was correlated only with the risk of osteoporosis [12, 13]. It is known that vitamin D3 modulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) [14], molecule involved in inflammation related to the diet [15, 16].

Today is growing acknowledgement that serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) variations make a substantial contribution to the pathogenesis of AN and BN. Neuroendocrine rhythms, including food intake, sleep, and reproductive activity together with mood, emotion, and cognition, are regulated by the midbrain raphe 5-HT system [17]. 5-HT is a monoamine neurotransmitter synthesized in the presynaptic neuron and released, during neurotransmission process, by presynaptic vesicles into the synaptic cleft; then it binds to receptors on the postsynaptic neuron where it is metabolised by the monoamine oxidase A enzyme. The 5-HT transporter (5-HTT) resides in the presynaptic membrane allowing reuptake of excess hormone from the synaptic cleft [18]. Relationship between 5-HT dysfunction and dysregulation of eating behaviour, mood, and general psychopathology was widely reported in AN and BN [4, 19, 20]. 5-HTT function has impact on early brain development, event-related synaptic plasticity, depression, and bipolar, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, schizophrenic, and eating disorders and it is a prime target for widely used antidepressants [17]. 5-HTT polymorphism is generated by a 44 bp deletion and involves repeat units 6–8, and it is located close to a “hot spot” for deletion mutagenesis (TGCAGC) in the linked polymorphic region; allelic variation in 5-HTT gene plays a role in the expression and modulation of complex traits and behaviour [17]. Associations between 5-HTT-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) variations and eating-disorder subphenotypes were demonstrated [21]. In this way 5-HTTLPR deleted (S) allele seems to represent a risk factor for eating disorders, especially for AN [22]. Patrick and Ames reported a regulation of 5-HT synthesis by vitamin D3 in patients with autism [23], attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and impulsive behaviour [24].

The aim of the work was to highlight the association among severe hypovitaminosis D3, reduction of vitamin D receptor (VDR), leukopenia, and 5-HTTLPR in patients with long-term AN and BN.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

All participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in this project and were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol and process were assessed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Aziende Sanitarie (CEAS) della Regione Umbria, Italy.

2.2. Patients

Blood samples of 18 patients affected by AN (n. 11) and/or BN (n. 7) were collected over a 15-month period (October 2014–January 2015) from the Department of Eating Disorder, Palazzo Francisci (USL 1 Umbria, Todi, Italy). The population consisted of all females; average age was 40 years (range 14–65 yrs). The chemical-clinic analyses were performed in the diagnostic laboratory of Todi (USL 1 Umbria, Italy). Whole blood, centrifuged cells, and serum were stored at −20°C until used for the assay of vitamin D3, immunoblotting, and genotyping analysis.

2.3. Materials

Standard vitamin D3 was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Missouri, USA); anti-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and anti-vitamin D receptor (VDR) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (California, USA).

2.4. Clinical Measures

Participants' weight and height were evaluated. The levels of thyroid hormones, hemochrome, hepatic and renal parameters, iron, ferritin, cholesterol, triglycerides, proteins, vitamin B12, and folic acid were measured.

2.5. Serum Assays for Vitamin D3

Serum vitamin D3 levels were measured by LC/MS/MS method. Before the analysis, the sample was prepared by adding 150 μL of precipitation reagent, containing Internal Standard, to 50 μL of patient serum or quality control serum; after 10 minutes of incubation, 50 μL of supernatant was injected. The signal from the analytes was measured against the calibration curve using the MultiQuant 2.1 software. For the analysis, Shimadzu UFLC-XR system, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan, equipped with a DGU-20A3 degasser, LC-20AD XR binary pump, SIL-20ACXR autosampler, CTO-20AC column oven, and a communication bus module CBM-20A was used. The UFLC system was connected to a 4000 QTRAP linear ion trap mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Concord, ON, Canada) equipped with an APCI source operated in the positive ionization mode. A 6-port automatic switching valve was interposed between the chromatographic system and the mass spectrometer. The controller software was Analyst version 1.6. The limit of detection (LLOD) for this assay was 0.67 μg/L. The low limit of quantification (LLOQ) was 2.25 μg/L, and the linearity was 2.25–250 μg/L. CVs were 6% at various concentrations across the analytical measurement range.

2.6. Electrophoresis and Western Blot Analysis

The analysis was performed as previously reported [25]. 30 μg of protein was used for SDS-PAGE electrophoresis in 10% polyacrylamide slab gel. Proteins were transferred into nitrocellulose for 90 min, and the membranes were blocked for 30 min with 0.5% no fat-dry milk in PBS, pH 7.5, and incubated overnight at 4°C with antibody anti-PPARγ or VDR. The blots were incubated with horseradish-conjugated secondary antibodies for 90 min. The enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reaction was performed with the ECL kit from Amersham (Rainham, Essex, UK). Immunoblots of proteins were reprobed after stripping. The apparent molecular weight of the proteins was calculated according to the migration of molecular size standard. The area density of the bands was evaluated by densitometry scanning and analyzed with Scion Image.

2.7. Genotyping of 5-HTTLPR

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from whole blood samples using QIAamp® DNA Mini kit (QIAGEN). Genotyping of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism was performed by polymerase chain reaction using the Phusion Hot Start II High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific). The following primer pair was used: 5′-GGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC-3′ (primer forward), 5′-GAGGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC-3′ (primer reverse) [26, 27]. The amplification of ~50 ng of gDNA was carried out after 30′′ of initial denaturation at 98°C for 35 cycles (denaturation at 98°C for 15′′, annealing at 69°C for 30′′, and extention at 72°C for 15′′) followed by a final extention at 72°C for 5′. 10 μL aliquots of each PCR product were resolved on 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis in 1x TBE buffer at 90 Volts. Genotype was determined by fragment sizes: 484 bp (S, short allele) and 528 bp (L, long allele). 100 bp SHARPMASS (Euroclone) was used as DNA ladder.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Three experiments performed in duplicate were performed for each analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and t-test was used for statistical analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results

AN (n. 11) and BN (n. 7) patients were selected to have normal blood test profile as thyroid hormones, hepatic and renal parameters, triglycerides, proteins, vitamin B12, and folic acid. Thus 18 patients were enrolled.

To highlight a possible association with immunity cells and to exclude defects of intestinal absorption and/or of metabolic disorders, the concentration of vitamin D3 was correlated to the total white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils (N), lymphocytes (L), iron, ferritin, transferrin, cholesterol, and glycemia (Table 1). All patients had normal levels of ferritin, transferrin, and glycemia, and only 3 patients showed low levels of iron and 1 patient low level of cholesterol, without changes of vitamin D.

Table 1.

Parameters considered for the study: ED = eating disorder; TO = time of onset (years); VD3 = vitamin D3 (16–60 ng/mL, normal values); WBC = white blood cells (3.6–9.6, normal values); N = neutrophils (42%–75%, 1.9 × 103–8.0 × 103, normal values); L = lymphocytes (20.5%–51.1%, 0.9 × 103–3.5 × 103, normal values); I = iron (55–150 μg/dL, normal values); F = ferritin (11–307 μg/dL, normal values); T = transferring (180–360 μg/dL, normal values); C = cholesterol (130–220 mg/dL, normal values); G = glycemia (60–110 mg/dL, normal values).

| N° | Age | ED | TO | VD3 | WBC | N | L | I | F | T | C | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 | BN | <10 | 10.4 | 8.6 | 79 | 15.0 | 64 | 50 | 207 | 166 | 72 |

| 2 | 18 | AN | <10 | 27.0 | 4.38 | 37.8 | 52.0 | 51 | 74.8 | 203 | 139 | 77 |

| 3 | 19 | BN | <10 | 35.0 | 7.75 | 70.5 | 20.9 | 126 | 30.5 | 313 | 144 | 85 |

| 4 | 41 | AN | <10 | 18.6 | 14.29 | 67.7 | 25.4 | 166 | 63 | 294 | 190 | 84 |

| 5 | 16 | BN | <10 | 13.3 | 4.19 | 53.7 | 36.5 | 140 | 59.9 | 254 | 146 | 76 |

| 6 | 55 | BN | <10 | 14.0 | 4.32 | 56 | 34.3 | 91 | 45.7 | 231 | 165 | 90 |

| 7 | 16 | AN | <10 | 22.0 | 4.27 | 60.4 | 28.8 | 59 | 60.7 | 212 | 110 | 70 |

| 8 | 40 | AN | <10 | 25.4 | 5.99 | 49.1 | 42.5 | 119 | 59.0 | 272 | 170 | 72 |

| 9 | 23 | BN | <10 | 18.1 | 4.69 | 66.1 | 22.5 | 85 | 18.8 | 242 | 163 | 72 |

| 10 | 18 | AN | <10 | 19.5 | 4.66 | 46.9 | 43.2 | 94 | 183.5 | 211 | 147 | 103 |

| 11 | 15 | AN | <10 | 17.5 | 4.70 | 60.0 | 31.2 | 98 | 54 | 208 | 213 | 77 |

| 12 | 18 | BN | <10 | 27.1 | 6.78 | 67.9 | 22.7 | 40 | 41.6 | 245 | 158 | 71 |

| 13 | 29 | AN | 15 | 3.60 | 2.91 | 54.4 | 36.6 | 67 | 43.1 | 248 | 158 | 82 |

| 14 | 14 | AN | <10 | 20.7 | 4.37 | 57.0 | 32 | 128 | 62.8 | 215 | 160 | 76 |

| 15 | 65 | AN | <10 | 30.0 | 6.62 | 66.0 | 22.6 | 70 | 81.3 | 266 | 157 | 74 |

| 16 | 44 | BN | 26 | 4.00 | 3.21 | 64.0 | 17.0 | 82 | 47.5 | 212 | 171 | 89 |

| 17 | 18 | AN | <10 | 31.6 | 4.81 | 47.9 | 40.7 | 48 | 65.8 | 262 | 226 | 80 |

| 18 | 18 | AN | <10 | 27.5 | 4.47 | 41.1 | 48.0 | 60 | 216 | 219 | 133 | 72 |

Of 18 patients, 13 presented normal levels of vitamin D3, between 16 and 60 ng/mL [28] (group A) and 5 patients were vitamin D3-deficient. We chose to divide patients with low levels of vitamin D3 in 2 groups: patients with 10–16 ng/mL vitamin D3 (group B, patients 1, 5, and 6) and patients with 1–4 ng/mL (group C, patients 13, 16).

The patients of groups A and B showed no changes in WBC; only patient n. 2 presented reduction of N and increase of L as a sign of possible chronic inflammation (Table 1). Interestingly, patients of group C had low level of total WBC, patient 13 low level of N (1.59 × 103), and patient 16 low level of L (0.71 × 103). These data could suggest, therefore, the existence of a relation between the low level of vitamin D3 and the WBC disorders.

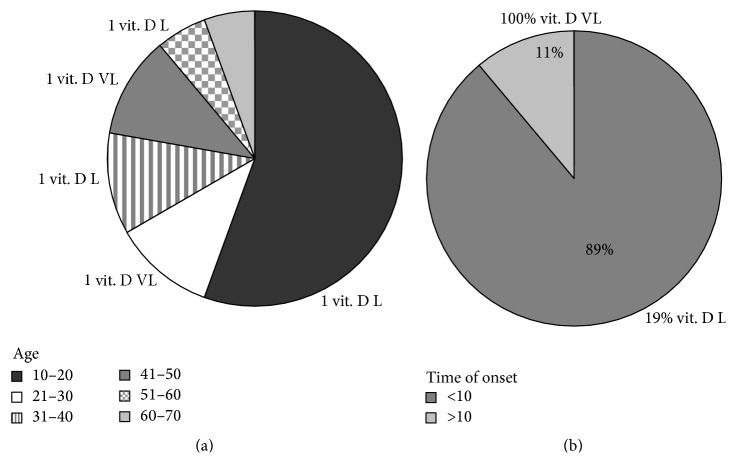

It is important to note that there was no correlation between the concentration of vitamin D3 and age. In fact, of 18 patients 10 were found to have an age in the range of 10–20 years, 2 in the range of 21–30 years, 2 in the range of 31–40 years, and 2 in the range of 41–50 years, and 1 patient was found to have an age in the range of 51–61 years and 1 in the range of 61–70 years (Figure 1(a)). Patients with low concentration of vitamin D3 had 16, 40, and 55 years and patients with very low level of vitamin D3 had 29 and 44 years (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

Level of vitamin D3 in patients affected with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. The data were analysed in relation to (a) the age and (b) time of the onset. Vit. D L, low level vitamin D3; Vit. D VL, very low level of vitamin D3.

Differently a relation between level of vitamin D3 and time of onset of the eating disorders was evident. In fact, of 18 patients 16 (89%) had a time of onset under 10 years and included patients with normal level and low level of vitamin D3, whereas 2 patients (11%) had a very long history of disease, one with AN (patient n. 13) and one with BN (patient n. 16), and both had very low level of vitamin D3 (Table 1 and Figure 1). The results suggested the importance of blood concentration of vitamin D3 in patients who had a very long history on eating disorders but remained unknown if these patients had also deficiency of VDR in the blood cells.

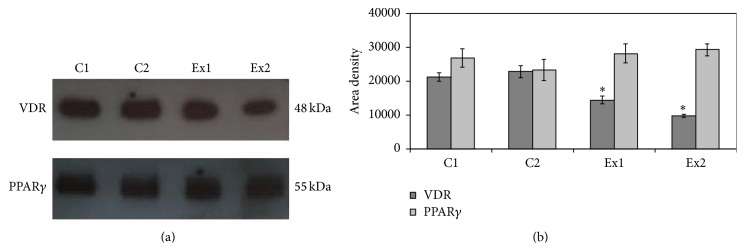

To address this question, the immunoblotting analysis was performed with a specific antibody against vitamin D3 receptor (VDR), in patients n. 13 (experimental 1, Ex1) and n. 16 (experimental 2, Ex2). Patient number 11 with normal level of vitamin D3 (control 1, C1) and patient number 5 with low level of vitamin D3 (control 2, C2), both with similar blood test profile, were chosen as controls.

The results highlighted that the band density of VDR, corresponding to 48 kDa apparent molecular weight, was less colored in Ex samples than in C samples (Figure 2(a)). The analysis of band density showed that VDR of Ex patients was significantly lower than that present in C patients (Figure 2(b)). In particular the VDR Ex1 was reduced 33% and Ex2 55% with respect to that of C patients whose value was very similar.

Figure 2.

Immunoblotting of vitamin D receptor (VDR) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). (a) Immunoblot of proteins was probed with specific antibodies and visualized by ECL in a patient with anorexia nervosa and normal level of vitamin D3 (C1), a patient with bulimia nervosa and slightly reduced level of vitamin D3 (C2), a patient with anorexia nervosa and very low level of vitamin D3 (Ex1), and a patient with bulimia nervosa and very low level of vitamin D3 (Ex2). Apparent molecular weight was calculated according to the migration of molecular size standards. (b) The area density was calculated with Scion Image programme on densitometry scanning; the data represent the mean ± SD of three experiments performed in duplicate. (Significance, ∗ P < 0.001 versus C1 and C2 sample.)

Since PPAR is regulated by vitamin D, we choose to test PPAR expression by immunoblotting to evaluate an activation of the inflammatory pathway related to the diet. No changes in protein level were found (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)).

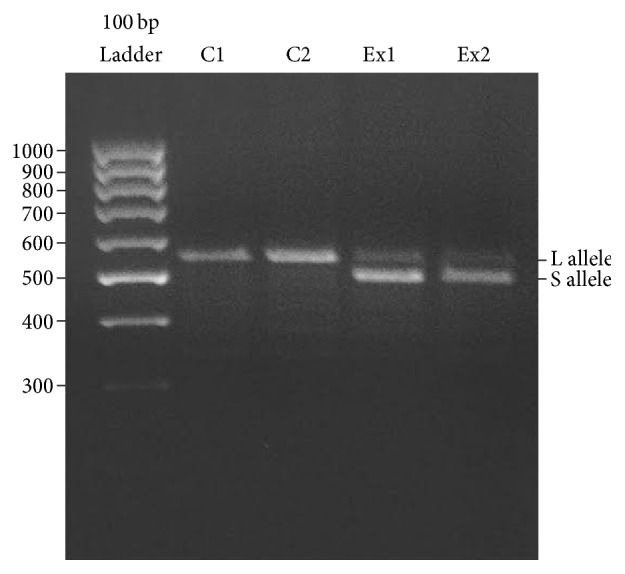

The two experimental patients with very low level of vitamin D3 and reduction of VDR had family problems, negativistic and depressive personality disturbances. It was demonstrated that 5-HTTLPR had an impact on the development of eating-disorder symptoms [29] and thus we studied 5-HTTLPR in C and Ex patients chosen for the study. Our results demonstrated the presence of 5-HTTLPR variant short allele (S) in both Ex samples with a very long history of AN (Ex1) and BN (Ex2) that was absent in C patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of 5-HTTLPR polymorphism amplified by PCR. The two patients with very low level of vitamin D3, E1, and E2 bear the short allele (S). The two control patients are instead homozygous for the long allele (L). The molecular weight of the corresponding bands is calculated according to the migration of molecular size standards (see Section 2).

3.2. Discussion

We herein reported the case of a woman with long-term AN and the case of a woman with long-term BN complicated by very low level of vitamin D, decrease of VDR, leukopenia, and the S allele of the 5-HT transporter polymorphism. This information emerged from a study of 18 AN (n. 11) and BN (n. 7) patients without blood test profile that suggested endocrine, metabolic, or absorption disorders. Because the goal of the work was to highlight associations of very low amount of vitamin D3 with other parameters in patients with eating disorders, as controls we chose two patients enrolled in the same study, one with AN who had normal levels of vitamin D3 and one with BN who had slightly low value of vitamin D. It was known that vitamin D3 deficiency increases the risk for acquiring several infectious diseases [30] since it had effects on innate and adaptive immunity and has antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory functions [31]. Our data showed that the only two patients who had severe hypovitaminosis presented reduction of WBC. At the moment we do not know if these patients had a defect of immunity response. It will be interesting in the future to investigate the association of immunodeficiencies and severe hypovitaminosis D3 in AN and BN patients. It could be very important because we showed that the blood cells of the two patients with severe hypovitaminosis D3 had a reduced content of the VDR and T cells have been shown to express the VDR and to be both direct and indirect targets of vitamin D3 [32]. We have recently demonstrated that VDR is located in nuclear lipid microdomains that act as platform for active chromatin anchoring so that vitamin D3 can regulate gene expression [33]. So we speculate on the possibility that the very low level of vitamin D3 and the reduction of VDR in blood cells might be responsible for the S allele of the 5-HTT polymorphism that was described to be related to eating disorder, as reported above [21]. On the other hand, the 5-HTTLPR S allele has been associated with differential susceptibility for anxiety and depression in multiple psychiatric disorders [34] and the two AN and BN patients under study presented these symptoms in their personal history. It could be due to the modification of the serotonergic systems that support emotion by 5-HTTLPR S allele that induced reduction of gene and protein expression [17]. In this way the transporter function was less efficient and consequently serotonin remained in the synapse longer and was recycled more slowly, resulting in a net reduction in circulating serotonin [17].

4. Conclusions

The most prominent feature of the study was the identification of a woman with long-term AN and a woman with long-term BN with severe hypovitaminosis D3. This study provides a unique insight into the association among the very low level of vitamin D3, the decrease of VDR, leukopenia, and 5-HTTLPR extended to emotional dysfunction. The results induce hypothesising that the severe hypovitaminosis D3 might be responsible for lack of inflammatory response and reduction in mood in patients with long-term eating disorders. The results could be useful to use vitamin D3 as anti-inflammatory molecule for novel therapies in the treatment of eating disorders.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by University of Udine, Italy, Associazione “Mi Fido di Te” ONLUS and Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Città di Castello, Italy.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Andersen A. E., Ryan G. L. Eating disorders in the obstetric and gynecologic patient population. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;114(6):1353–1367. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c070f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharan P., Sundar A. S. Eating disorders in women. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;57(6, supplement 2):S286–S295. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.161493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Culbert K. M., Racine S. E., Klump K. L. What we have learned about the causes of eating disorders—a synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56(11):1141–1164. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaye W. Neurobiology of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Physiology & Behavior. 2008;94(1):121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matyjaszek-Matuszek B., Lenart-Lipińska M., Woźniakowska E. Clinical implications of vitamin D deficiency. Przegląd Menopauzalny. 2015;14(2):75–81. doi: 10.5114/pm.2015.52149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee A., Khemka V. K., Ganguly A., Roy D., Ganguly U., Chakrabarti S. Vitamin D and Alzheimer’s disease: neurocognition to therapeutics. International Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2015;2015:11. doi: 10.1155/2015/192747.192747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin Z., Li W. The roles of vitamin D and its analogs in inflammatory diseases. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;15:1–20. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150915111557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimitrov V., White J. H. Species-specific regulation of innate immunity by vitamin D signaling. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Pinto R., Pietropaoli D., Chandar A. K., Ferri C., Cominelli F. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and vitamin D deficiency. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2015;21(11):2708–2717. doi: 10.1097/mib.0000000000000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W.-C., Zheng C.-M., Lu C.-L., et al. Vitamin D and immune function in chronic kidney disease. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2015;450:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morales E., Sanchez-Solis M., Garcia-Marcos L. Vitamin D metabolism genes in asthma and atopy. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;15(11):913–926. doi: 10.2174/1389557515666150519105944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modan-Moses D., Levy-Shraga Y., Pinhas-Hamiel O., et al. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in adolescent inpatients diagnosed with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2015;48(6):607–614. doi: 10.1002/eat.22347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misra M., Klibanski A. Bone health in anorexia nervosa. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2011;18(6):376–382. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32834b4bdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee T.-I., Kao Y.-H., Chen Y.-C., Tsai W.-C., Chung C.-C., Chen Y.-J. Cardiac metabolism, inflammation, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors modulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in diabetic rats. International Journal of Cardiology. 2014;176(1):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu W. X., Wang T., Zhou F., et al. Voluntary exercise prevents colonic inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obese mice by up-regulating PPAR-γ activity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2015;459(3):475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ooi J. H., Li Y., Rogers C. J., Cantorna M. T. Vitamin D regulates the gut microbiome and protects mice from dextran sodium sulfate-induced coliti. Journal of Nutrition. 2013;143(10):1679–1686. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heils A., Teufel A., Petri S., et al. Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1996;66(6):2621–2624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadkowski M., Dennis B., Clayden R. C., et al. The role of the serotonergic system in suicidal behaviour. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2013;9:1699–1716. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s50300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaye W. H., Gwirtsman H. E., George D. T., Ebert M. H. Altered serotonin activity in anorexia nervosa after long-term weight restoration: does elevated cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid level correlate with rigid and obsessive behavior? Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48(6):556–562. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810300068010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monteleone P., Brambilla F., Bortolotti F., Maj M. Serotonergic dysfunction across the eating disorders: relationship to eating behaviour, purging behaviour, nutritional status and general psychopathology. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30(5):1099–1110. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steiger H. Eating disorders and the serotonin connection: state, trait and developmental effects. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2004;29(1):20–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calati R., De Ronchi D., Bellini M., Serretti A. The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and eating disorders: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44(3):191–199. doi: 10.1002/eat.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick R. P., Ames B. N. Vitamin D hormone regulates serotonin synthesis. Part 1: relevance for autism. The FASEB Journal. 2014;28(6):2398–2413. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-246546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick R. P., Ames B. N. Vitamin D and the omega-3 fatty acids control serotonin synthesis and action. Part 2. Relevance for ADHD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and impulsive behaviour. The FASEB Journal. 2015;29(6):2207–2222. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-268342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartoccini E., Marini F., Damaskopoulou E., et al. Nuclear lipid microdomains regulate nuclear vitamin D3 uptake and influence embryonic hippocampal cell differentiation. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2011;22(17):3022–3031. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-03-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payton A., Gibbons L., Davidson Y., et al. Influence of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms on cognitive decline and cognitive abilities in a non demented elderly population. Molecular Psychiatry. 2005;10(12):1133–1139. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J., Kang Q., Jiang W., et al. The 5-HTTLPR confers susceptibility to anorexia nervosa in Han Chinese: evidence from a case-control and family-based study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119378.e0119378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holick M. Vitamin D. In: Ross A. C., editor. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. pp. 1–1616. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akkermann K., Kaasik K., Kiive E., Nordquist N., Oreland L., Harro J. The impact of adverse life events and the serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism on the development of eating disorder symptoms. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46(1):38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watkins R. R., Lemonovich T. L., Salata R. A. An update on the association of vitamin D deficiency with common infectious diseases. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2015;93(5):363–368. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amaya-Mejía A. S., O'Farrill-Romanillos P. M., Galindo-Pacheco L. V., et al. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with common variable immunodeficiency, with autoimmune diseases and bronchiectasis. Revista Alergia Mexico. 2013;60(3):110–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J., Bruce D., Cantorna M. T. Vitamin D receptor expression controls proliferation of naïve CD8+ T cells and development of CD8 mediated gastrointestinal inflammation. BMC Immunology. 2014;15, article 6 doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-15-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cascianelli G., Villani M., Tosti M., et al. Lipid microdomains in cell nucleus. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2008;19(12):5289–5295. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Homberg J. R., Lesch K.-P. Looking on the bright side of serotonin transporter gene variation. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69(6):513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]