Abstract

Background

Along with changes in cannabis laws in the United States and other countries, new products for consuming cannabis are emerging, with unclear public health implications. Vaporizing or “vaping” cannabis is gaining popularity, but little is known about its prevalence or consequences.

Methods

This study characterized the prevalence and current patterns of vaping cannabis among a large national sample of cannabis users. An online survey was distributed through Facebook ads targeting individuals with interests related to cannabis use. The sample comprised 2,910 cannabis users (age: 18-90, 84% male, 74% Caucasian).

Results

A majority (61%) endorsed lifetime prevalence of ever vaping, 37% reported vaping in the past 30 days, 20% reported vaping more than 100 lifetime days, and 12% endorsed vaping as their preferred method. Compared to those that had never vaped, vaporizer users were younger, more likely to be male, initiated cannabis at an earlier age, and were less likely to be African American. Those that preferred vaping reported it to be healthier, better tasting, produced better effects, and more satisfying. Only 14% reported a reduction in smoking cannabis since initiating vaping, and only 5% mixed cannabis with nicotine in a vaporizer. Many cannabis users report vaping cannabis, but currently only a small subset prefers vaping to smoking and reports frequent vaping.

Conclusion

Increases in availability and marketing of vaping devices, and the changing legal status of cannabis in the United States and other countries may influence patterns of use. Frequent monitoring is needed to assess the impact of changing cannabis laws and regulations.

Keywords: Cannabis, Marijuana, Vaping, Facebook, E-Cigarettes, Survey

1. INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of using electronic cigarettes (e-cigs) to vaporize nicotine is rapidly growing and generating debate and research on its potential benefit and harm (Arrazola et al., 2015; Gostin and Glasner, 2014; Hajek et al., 2014). Similarly, devices now use similar electronic technologies to vaporize cannabis, and this practice is gaining popularity as an alternative to smoking cannabis products. Vaporizing, or ‘vaping’ cannabis refers to the process of heating cannabis concentrates, liquid, or plant material to a temperature that releases an aerosolized mixture of water vapor and active cannabinoids, which is then consumed by inhalation. Vaping devices for cannabis vary widely, from large tabletop units to small pen-style devices that are similar to e-cigs, and depending on the device, additional substances such as flavoring agents can be added to enhance the vaping experience (Giroud et al., 2015). Few studies have examined the practice of vaping cannabis, and little is known about its prevalence, patterns, or consequences.

Two small survey studies suggest that cannabis users believe vaping to be less harmful to their health than typical combustible smoking methods (Etter, 2015; Malouff et al., 2014), which is similar to tobacco users perceptions of e-cigs (Zhu et al., 2013). This theoretical benefit relates to reduction in the ingestion of potentially harmful cannabis smoke, which contains tar (phenols and carcinogens such as benzopyrene and benzanthracene), ammonia, hydrogen cyanide, and nitrosamines in comparable amounts to tobacco smoke (Tashkin, 2013), a benefit that may extend to concerns about second-hand cannabis smoke. A laboratory study evaluating contents of cannabis smoke and vapor found that the vaporizer extracted more active cannabinoids with fewer carcinogenic byproducts than smoking at 230 degrees Celsius, but lower temperatures extracted minimal amounts of cannabinoids, suggesting that temperature control is important (Pomahacova et al., 2009). A study directly comparing the impact of smoking vs. vaping cannabis reported fewer respiratory problems associated with vaping (Earleywine and Barnwell, 2007), supporting the contention that vaping affords a harm reduction effect on respiratory disorders caused by cannabis smoking.

Aside from this potential health advantage of vaping over smoking, initial surveys have identified a number of other appealing aspects of vaping (Etter, 2015; Malouff et al., 2014). First, some believe that vaping provides a more efficient way to use cannabis (more positive effect for less cost or effort). Objective evidence for differences in psychoactive effects between vaping and smoking is lacking, however; a laboratory study of three cannabis cigarette concentrations (1.7%, 3.4%, and 6.8% THC) did not show clear differences in ratings of “high” between vaping and smoking, but 14 of 18 participants reported preference for vaping, and expired carbon monoxide levels were lower after vaping (Abrams et al., 2007). Survey respondents identified two other positive features of vaping: better taste and the ability to use it more discreetly with little or no smell (Etter, 2015; Malouff et al., 2014).

As with use of e-cigs, public health concerns related to vaping cannabis warrant attention (Budney et al., 2015). First, little is known about the potential negative effects of acute and long-term inhalation of aerosols emitted by vaping devices. While vaping eliminates many of the potentially harmful byproducts of cannabis smoke (Pomahacova et al., 2009), more information is needed to determine the overall safety profile of vaporization. Second, the perceived positive attributes of vaping cannabis mentioned above could result in increased prevalence or frequency of cannabis use. Perceptions that vaping is a safer, better tasting experience that provides a more efficient high and can be used discreetly in locations where smoking cannot occur could contribute to earlier initiation of use, more rapid escalation of use, more frequent use, and therefore more problematic use of cannabis. Last is the contribution of vaping cannabis to an emerging “vaping culture” (Gostin and Glasner, 2014), which includes marketing of vaping devices not just for nicotine or cannabis, but for inhaling non-psychoactive flavors, which could increase the prevalence and decrease age of onset of cannabis (or nicotine) use via vaping devices.

The primary goal of the present online survey was to characterize age of onset, prevalence, and current patterns of vaping among cannabis users. Facebook was utilized to facilitate rapid data collection in a large, national sample of cannabis users and to obtain initial benchmarks for vaping. Previous studies have begun to assess trends in vaporizer use (Etter, 2015; Malouff et al., 2014), however, sample sizes were small and only included individuals that reported vaping cannabis and/or nicotine, so prevalence among cannabis users, and differences between cannabis users that vaped vs. never vaped were not assessed. To address these gaps, this survey assessed: 1) lifetime and current prevalence of vaping, 2) demographic differences between those who vape and those who do not, 3) reasons for vaping, 4) comparisons between smoking and vaping, 5) within-person vaping and smoking patterns, and 6) the relationship between vaping and other substance use (e.g., tobacco use, vaping flavors).

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants and recruitment

Participants were adult (≥ 18 years of age) cannabis users from the United States who responded to advertisements on Facebook seeking volunteers to complete an online survey about cannabis use. Advertisements for the survey were shown to a targeted audience of cannabis users through proprietary marketing algorithms that utilized Facebook users’ self-reported interests. Examples of the self-reported interests that were used to target cannabis users included organizations with pro-cannabis interests such as NORML or High Times Magazine, legalization movements (e.g., Colorado Amendment 64), and popular media that were automatically suggested by Facebook (e.g., comedians and musicians/bands that were associated with cannabis use interests). Participants were recruited in two phases; phase 1 was collected over a 35 day period in October and November, 2014, and phase 2 over an 8 day period in February, 2015. The advertisements contained a hyperlink that directed potential participants to a survey hosted on Qualtrics with all automatic data collection features disabled to preserve anonymity. Prior to completing the survey, participants were directed to an informed consent page approved by Dartmouth College’s Institutional Review Board. Respondents that consented were then directed to the survey, which was designed to take < 10 minutes to complete, and no compensation was provided.

2.2 Survey

The survey comprised 63 and 72 items in phase 1 and 2, respectively. Survey items included: demographics (i.e., age, gender, race, education, income), cannabis use characteristics by route of administration (i.e., age of onset, lifetime prevalence and current patterns of cannabis smoking and vaping), reasons and preferences for vaping cannabis, types of vaporizer devices used, comparisons between smoking and vaping cannabis, and other substance use. Cannabis dependence was assessed using the Severity of Dependence Scale (Gossop et al., 1995) and tobacco dependence was assessed using the Fagerstrom Test of Cigarette Dependence (FTCD: Heatherton, et al., 1991). Additional questions assessing demographics, vaping patterns, and other substance use were added to the survey in phase 2 but were not included in the current analysis. Survey results were analyzed using descriptive statistics, and comparisons between individuals that ever vaped vs. never vaped were conducted using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Participant characteristics

Advertisements for the survey were shown to 168,894 people, out of whom 3,708 (2.2%) clicked the advertisement link, and of which 2,910 (1.7%) were included in the final sample. Respondents were excluded if they: did not consent (N = 60), did not report ever using cannabis (N = 103), responded incorrectly to a data check question asking them to choose the number 4 from a 5-choice categorical response (N = 47), were not from the United States (N = 13), or if they failed to respond any of these items (N = 575). A total of 2,357 of the 2,910 respondents (81%) finished the survey. The mean percentage of missing data for each item was 4% (range 0% to 23%). All available data from every respondent was used in the analyses.

A comparison with 2,014 US state census data indicated that the proportional distribution of participants from each state corresponded closely to the population distribution across US states (r = 0.94, p<.001). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Respondents were primarily male (84%) and Caucasian (74%), with a mean age of 32.4 (SD 15.5). The sample contained somewhat fewer minorities than the general population (74% white, 8% African-American, and 15% Hispanic), and were less educated (with half having a high school education or less).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total (n=2,910) |

Ever Vaped (n=1,783) |

Never Vaped (n=1,127) |

p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or % | M (SD) or % | M (SD) or % | ||

| Age | 32.4 (15.5) | 28.6 (13.1) | 38.4 (17.0) | <.001 |

| Gender | <.001 | |||

| Male | 84.3% | 63.4% | 36.6% | |

| Female | 15.3% | 49.7% | 50.3% | |

| Race | <.001 | |||

| Caucasian | 74.4% | 63.4% | 36.6% | |

| African-American | 7.5% | 41.9% | 58.1% | |

| Hispanic | 14.6% | 59.6% | 40.4% | |

| Other | 3.5% | 60.6% | 39.4% | |

| Education | NS | |||

| High School or less | 53.2% | 62.3% | 37.7% | |

| Some College | 32.4% | 58.7% | 41.3% | |

| Bachelor’s or higher | 14.4% | 63.2% | 36.8% | |

| Age of First Cannabis Use | ||||

| Any Method | 15.7 (4.4) | 15.2 (3.5) | 16.5 (5.3) | <.001 |

| Smoking | 15.6 (4.1) | 15.0 (2.6) | 16.5 (5.6) | <.001 |

| Vaping | N/A | 24.2 (12.2) | N/A | |

| Frequency of Current (past 30 days) Cannabis Smoking | ||||

| Occasional (<11 days) | 35.4% | 41.1% | 58.9% | |

| Daily | 40.3% | 73.3% | 26.7% | |

: Note: t-tests and chi square tests were used to assess group differences between respondents who ever vaped cannabis compared to those who never vaped.

3.2 Prevalence and patterns of vaping cannabis

Sixty-one percent (n=1,783) of respondents reported lifetime use of a vaporizer to administer cannabis (i.e., ever vaped). Only three respondents reported ever vaping with no lifetime cannabis smoking. Mean age of first cannabis use was 15.7 years (SD = 4.4). Among those who had ever vaped, first time cannabis vape experience occurred a mean of 8.5 years after first cannabis use. The most popular type of vaping device endorsed was a vaping pen (45%), followed by a tabletop device (23%), a portable device (15%), and an e-cig (11%).

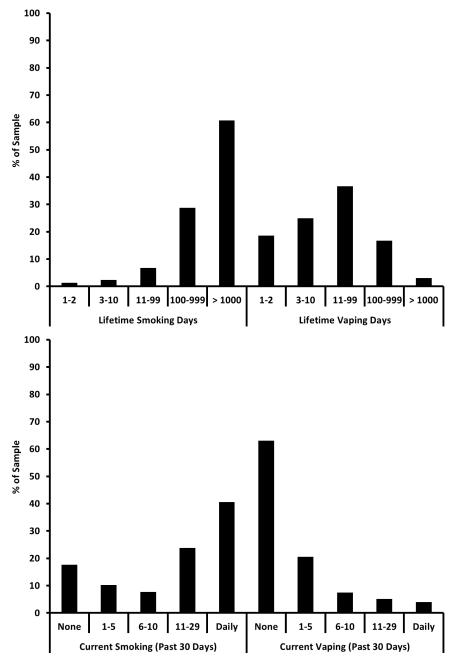

Patterns of lifetime and current (past 30 days) cannabis smoking and vaping are presented in Figure 1. The majority of the sample comprised highly experienced cannabis smokers, with 90% reporting 100 or more lifetime days of smoking. Approximately two-thirds of the sample reported frequent cannabis smoking (i.e., at least 11 out of the past 30 days). Vaping cannabis was less frequent, with about 20% reporting 100 or more lifetime days of vaping, and less than 10% reported frequent current vaping (i.e., 11 or more of the past 30 days).

Figure 1.

Days of lifetime cannabis use (top panel) and current (past 30 days) cannabis use (bottom panel) by smoking and vaping. The horizontal axes display the categorical response options for lifetime and current days of cannabis use, and the vertical axes display proportion of the respondents that chose each option.

Of those that endorsed vaping in the past 30 days, the vast majority reported dual use (i.e., smoking and vaping cannabis); 76% reported that smoking remained their most common route of administration, 21% reported smoking and vaping at similar rates, and 3% reported vaping more frequently than smoking. A minority (12%) reported vaping as their preferred route of administration, and only seven respondents endorsed vaping exclusively. Since initiating vaping, 75% reported that their rate of cannabis smoking remained the same, while 14% reported a decrease and 11% reported an increase.

3.3 Characteristics of vaporizer users

Comparisons between those that ever vaped and never vaped are presented in Table 1. Male cannabis users were more likely to have ever vaped than females (63% vs. 50%; χ 2(2, N = 2,906) = 30.0, p < .001). African-Americans were less likely to endorse ever vaping than other ethnic groups (χ 2(3, N = 2,822) = 37.8, p < .001). Those who had ever vaped cannabis were younger than those who had not (t(2,233) = 15.3, p < .001), and reported a younger age of initiation of cannabis use (t(2,868) = 8.1, p<.001). Daily cannabis smokers were more likely to report ever vaping than occasional (i.e., <11 days of use in the last 30) cannabis smokers, (73% vs 41%; χ 2 (1, N = 2,202) = 234.1, p<.001], and to report vaping in the past 30 days [42% vs 19%; χ 2 (1,N = 1,271) = 63.9, p<.001]. No differences in education or income were observed between those that ever vaped vs never vaped.

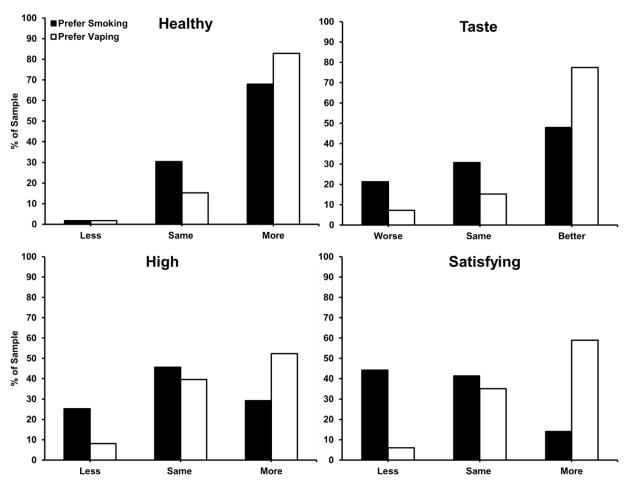

3.4 Comparisons between smoking and vaping and reasons for vaping cannabis

Figure 2 presents comparisons between vaping and smoking for those that reported any lifetime experience with vaping. Among those that preferred vaping to smoking, responses across all comparisons favored vaping (i.e., healthier, better taste, better high, more satisfying). Regardless of preference for vaping or smoking, a majority of respondents (72%) endorsed vaping as healthier than smoking, and a smaller majority (55%) reported that vaping tasted better than smoking. Ratings of high and satisfying were more evenly distributed and greater differences between preference for vaping or smoking emerged. For ratings of high, 52% of those that preferred vaping endorsed a more substantial high from vaping, while 46% of those that preferred smoking thought both methods produced a similar high. For satisfying, 59% of those that preferred vaping endorsed feeling more satisfied with vaping, while 44% of those that preferred smoking reported less satisfaction from vaping.

Figure 2.

Questions assessing the effects of vaping cannabis compared to smoking cannabis on health effects, taste, high, and satisfaction among participants that preferred smoking (black bars), and vaping (white bars). The horizontal axes display the categorical response options for each question and the vertical axes display the percent of the sample that chose each option

3.5 Relationship between vaping cannabis and other substances

Lifetime tobacco use prevalence did not differ between those that ever vaped vs never vaped cannabis (82% for both groups), nor did mean age of first tobacco use (vaped: M = 14.7, SD= 3.4; never vaped: M = 14.9, SD = 4.2). Those who ever vaped cannabis were more likely to report e-cig use [75% vs 49%; χ2 (1,N = 2,037) = 143.9, p<.001], and mean age of first e-cig use was younger for those who had vaped cannabis (23.9 vs 32.5, t(1,281) = 11.6, p<.001). Of note, few respondents (5%) reported ever mixing nicotine and cannabis in a vaporizer, and only 2% reported mixing nicotine and cannabis at all in the past 30 days.

Thirty-two percent of the total sample reported vaping flavors (either with or without nicotine/cannabis) during their lifetime, with a mean age of first use of 24.8 years (SD = 12.0). Of these, 67% vaped flavors and nicotine together the first time they vaped a flavor, while 21% vaped a flavor alone and 11% vaped flavors and cannabis the first time they vaped a flavor. Respondents that endorsed ever using tobacco or nicotine were more likely to have vaped flavors than non-tobacco users [38% vs 16%; χ2 (1,N = 2,540) = 79.8, p<.001]. Forty-one percent of those that ever vaped flavors reported current (past 30 days) use of flavors; of which 83% mixed flavors with nicotine and 17% mixed flavors with cannabis.

3.6 Inexperienced vs. experienced vaporizer users

Exploratory analyses using chi square and t-tests were conducted to compare inexperienced vs. experienced vaporizer users (i.e., lifetime use on 10 or less days vs 100 or more) on demographic and vaping characteristics. Compared to inexperienced vapers, experienced vapers were slightly more likely to be male (88% vs. 84%, p<.05) and more educated (e.g., 25% vs 10% had a bachelor’s degree or higher, p<.001). There were no differences between groups on race or severity of cannabis dependence. Experienced vapers were also more experienced cannabis smokers (85% vs. 60% reported smoking 1000 or more lifetime smoking days, p<.001, and 85% vs. 72% reported smoking at least 11 out of the past 30 days, p<.001). Experienced vapers rated vaping as more positive than smoking (i.e., more satisfying, healthier, better high, better taste, p’s<.001). Experienced vapers were more likely to use tabletop and/or portable devices and less likely to use pen style devices (36% vs 45%, p<.01).

4. DISCUSSION

The majority of cannabis users in this sample had tried vaping cannabis, but frequent vaping was less common, and only a small subset of cannabis users preferred vaping to smoking, or indicated that vaping had substantially changed their frequency of smoking cannabis. These findings are similar to a previous report indicating that only a minority of individuals report vaping as primary method for cannabis use (Earleywine and Barnwell, 2007). Although detailed data on the marketing of vaping devices for cannabis are not yet available, trends in use and marketing of e-cigs suggest that vaping nicotine is becoming increasingly popular (Arrazola et al., 2015). Moreover, the US market for legal cannabis in the limited amount of states having operational cannabis dispensaries nearly doubled from 1.5 billion in 2013 to 2.7 billion in 2014 (Budney et al., 2015). As legalization of medical and recreational cannabis gains momentum and the cannabis industry grows alongside it, one would expect that trends in cannabis vaping will parallel the e-cig trend and increase rapidly. Repeated monitoring to inform policy-related decisions related to cannabis and vaping devices is essential; the survey method used here, Facebook, offers one avenue for facilitating frequent, low cost monitoring of this phenomenon.

Also similar to prior studies (Etter, 2015; Malouff et al., 2014), cannabis users who preferred vaping rated it as a generally more positive and potentially reinforcing experience than smoking, though laboratory studies are needed to confirm the subjective and reinforcing effects of vaping cannabis. Similar to e-cigs for nicotine (Gostin and Glasner, 2014), these perceived positive aspects of vaping cannabis may have both positive and negative implications (Budney et al., 2015). As discussed above, vaping cannabis reduces the carcinogens ingested with smoking cannabis (Pomahacova et al., 2009). However, a major concern with vaping is that its other positive attributes (i.e., more satisfying, better taste and effect, more discreet) have the potential to increase prevalence and frequency of cannabis use, leading to greater initiation, increased rates of cannabis use disorder, and other deleterious effects such as driving under the influence. Of note, users in the current survey did not generally report an increase or a decrease in use of cannabis since vaping; however, it is important to note that retrospective reports of cannabis use may be biased by a number of factors. Longitudinal studies that include more valid measures of cannabis use are needed to better understand how the increased presence and awareness of vaping impacts initiation, frequency, and problems associated with cannabis use.

Vaporizer users tended to be younger, male, less likely African American, earlier initiators and more frequent cannabis users, consistent with previous findings (Etter, 2015), and with cannabis users overall (Haberstick et al., 2014; Stinson et al., 2006). A few possibilities for this profile merit mention. First, younger age is generally associated with greater sensation and novelty seeking (e.g., Steinberg et al., 2009), and as such younger cannabis users may be more attracted to the novelty of vaping compared to older individuals. Second, heavier cannabis users might be (a) more likely to be exposed to vaping devices, and (b) more likely to invest in a more expensive method/device for using cannabis. Third, males are more likely and African Americans less likely to use cannabis in general and males tend to be higher than females on sensation seeking. Replication of these profiles using different sampling methods is clearly needed.

Nicotine e-cig use was greater among those that ever vaped cannabis, but relatively few reported mixing nicotine and cannabis in a vaporizer, which is similar to a previous report assessing 96 vaporizer users (Malouff et al., 2014), but still somewhat unexpected given the common pattern of co-use of cannabis and tobacco (Agrawal et al., 2012; Ramo and Prochaska, 2012). Nonetheless, it remains of some concern that positive experiences associated with vaping cannabis and nicotine individually may negatively impact quit rates for cannabis or tobacco use, especially given the large proportion that report a history of vaping both substances. A related concern to address is whether vaping cannabis increases risk for initiating e-cigs, and whether this leads to initiation of combustible tobacco use. Last, most respondents who vaped both substances reported mixing flavors with nicotine, but not with cannabis. Flavored nicotine mixtures are heavily marketed for e-cigs, and presumably appeal to youth and prompt initiation; flavored cannabis preparations for vaping are not currently available to our knowledge. If the vaping trend continues to escalate, flavored cannabis mixtures or prepared mixtures of cannabis and tobacco may become more widely available.

Limitations to this study warrant mention. First, the study comprised a self-selected sample of cannabis users recruited via Facebook. Although the sample represented the geographic regions of the US, it over represented males and underrepresented ethnic minorities, and may not generalize to cannabis users across a broader demographic range, or to those that are less willing to share information online. Although national survey data suggest that the prevalence of cannabis is greater in males (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015), it is likely that our recruitment methodology contributed to the specific profile of this sample. Previous studies using Facebook to recruit cannabis users report capturing similar ratios for gender and ethnicity (i.e., Ramo and Prochaska, 2012). Note that Facebook ad campaigns can be readily manipulated to target specific samples; ours targeted individuals that “liked” Facebook pages associated with pro-cannabis interests, which may have resulted in targeting a greater proportion of Caucasian and male respondents. Second, data were comprised of individuals across the United States. Although results were similar to the two smaller international surveys (Etter, 2015; Malouff et al., 2014), prevalence and patterns of use may align differently within US states (Borodovsky et al., 2015), and internationally depending on cannabis laws and other environmental contexts. Third, we did not assess reasons for cannabis use in general, and as a result it is unclear if using cannabis for medical and/or recreational purposes impacts rates of vaping cannabis. Questions assessing reasons for vaping were limited to those with vaping experience, so reasons or perceptions of vaping between those who vaped and those who had not could not be compared. Fourth, all available data were included in the analyses, including data from individuals that did not report age (23% of the sample). Last, although this survey was distributed to individuals 18 years of age and older, it is possible that some respondents that completed the survey were under the age of 18.

Many cannabis users have initiated vaping, but currently few appear to be vaping frequently and report preferring vaping to smoking. Those that do vape consider it to be a safer, more positive experience than smoking. Increases in availability and marketing of vaping devices, and the changing legal status of cannabis in the United States and other countries may influence patterns of use (Daniulaityte et al., 2015). Using Facebook or other social media platforms can facilitate rapid, repeated assessments of developing trends in cannabis use. Future surveys should assess patterns and perceptions at regular intervals in a broader range of the population to better document and respond to the changing landscape of cannabis use.

Highlights.

Online survey assessed current patterns of vaping in large sample of cannabis users

The majority of users had tried vaping cannabis but frequent vaping was not common

Few preferred vaping cannabis to smoking

Those that prefer vaping consider it to be a safer, more positive experience

Using Facebook can facilitate rapid repeated assessments of cannabis vaping

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by NIH-NIDA grants R01-DA032243, P30-DA029926, and T32-DA037202; the NIH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

DCL, BSC, JDS and AJB designed the survey. BSC managed online recruitment efforts. DCL, BSC and JTB conducted the analyses of the data. DCL and AJB wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Abrams DI, Vizoso HP, Shade SB, Jay C, Kelly ME, Benowitz NL. Vaporization as a smokeless cannabis delivery system: a pilot study. Clin. Pharmacol. Thera. 2007;82:572–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100200. doi: 6100200 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Budney AJ, Lynskey MT. The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: a review. Addiction. 2012;107:1221–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Apelberg BJ, Bunnell RE, Choiniere CJ, King BA, Cox S, McAfee T. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2014. MMWR. 2015;64:381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky JT, Crosier BS, Lee DC, Sargent JD, Budney AJ. Smoking, Vaping, Eating: Is Legalization Impacting the Way People use Cannabis? 2015. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Budney AJ, Sargent JD, Lee DC. Vaping cannabis (marijuana): parallel concerns to e-cigs? Addiction. 2015;110:1699–1704. doi: 10.1111/add.13036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality . 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Nahhas RW, Wijeratne S, Carlson RG, Lamy FR, Martins SS, Boyer EW, Smith GA, Sheth A. “Time for dabs”: analyzing Twitter data on marijuana concentrates across the US. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;155:307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earleywine M, Barnwell SS. Decreased respiratory symptoms in cannabis users who vaporize. Harm Reduct. J. 2007;4 doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter JF. Electronic cigarettes and cannabis: an exploratory study. Eur. Addict. Res. 2015;21:124–130. doi: 10.1159/000369791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroud C, de Cesare M, Berthet A, Varlet V, Concha-Lozano N, Favrat B. E-cigarettes: a review of new trends in cannabis use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015;12:9988–10008. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120809988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Darke S, Griffiths P, Hando J, Powis B, Hall W, Strang J. The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS): psychometric properties of the SDS in English and Australian samples of heroin, cocaine and amphetamine users. Addiction. 1995;90:607–614. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9056072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostin LO, Glasner AY. E-cigarettes, vaping, and youth. JAMA. 2014;312:595–596. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberstick BC, Young SE, Zeiger JS, Lessem JM, Hewitt JK, Hopfer CJ. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol and cannabis use disorders in the United States: results from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;136:158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, Etter JF, Benowitz N, Eissenberg T, McRobbie H. Electronic cigarettes: review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit. Addiction. 2014;109:1801–1810. doi: 10.1111/add.12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Rooke SE, Copeland J. Experiences of marijuana-vaporizer users. Subst. Abuse. 2014;35:127–128. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.823902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomahacova B, Van der Kooy F, Verpoorte R. Cannabis smoke condensate III: the cannabinoid content of vaporised cannabis sativa. Inhal. Toxicol. 2009;21:1108–1112. doi: 10.3109/08958370902748559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo D, Prochaska J. Prevalence and co-use of marijuana among young adult cigarette smokers: an anonymous online national survey. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2012;7:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Albert D, Cauffman E, Banich M, Graham S, Woolard J. Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: evidence for a dual systems model. Dev. Psychol. 2008;44:1764–1778. doi: 10.1037/a0012955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Pickering R, Grant BF. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychol. Med. 2006;36:1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. doi: S0033291706008361 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin DP. Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2013;10:239–247. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201212-127FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S-H, Gamst A, Lee M, Cummins S, Yin L, Zoref L. The use and perception of electronic cigarettes and snus among the US population. Plos One. 2013;8:e79332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]