Abstract

Carbonic anhydrases (CAs) are enzymes that catalyze the hydration/dehydration of CO2/HCO3− with rates approaching diffusion-controlled limits (kcat/KM ~ 108 M− s−1). This family of enzymes has evolved disparate protein folds that all perform the same reaction at near catalytic perfection. Presented here is a structural study of a β-CA (psCA3) expressed in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in complex with CO2, using pressurized cryo-cooled crystallography. The structure has been refined to 1.6 Å resolution with Rcryst and Rfree values of 17.3 and 19.9%, respectively, and is compared with the α-CA, human CA isoform II (hCA II), the only other CA to have CO2 captured in its active site. Despite the lack of structural similarity between psCA3 and hCA II, the CO2 binding orientation relative to the zinc-bound solvent is identical. In addition, a second CO2 binding site was located at the dimer interface of psCA3. Interestingly, all β-CAs function as dimers or higher-order oligomeric states, and the CO2 bound at the interface may contribute to the allosteric nature of this family of enzymes or may be a convenient alternative binding site as this pocket has been previously shown to be a promiscuous site for a variety of ligands, including bicarbonate, sulfate, and phosphate ions.

Carbonic anhydrases (CAs, EC 4.2.1.1) are metalloenzymes that catalyze the reversible interconversion of CO2 and HCO3−. All CAs follow a two-step ping-pong mechanism. In the hydration direction, CO2 enters the active site where it undergoes nucleophilic attack by a metal-bound hydroxide (the metal is a zinc ion, in most cases), is converted into HCO3−, and then is displaced by a water molecule. In the second step of the reaction, the metal-bound water transfers a proton to the bulk solvent to regenerate the metal-bound hydroxide in readiness for the next cycle of catalysis.1,2

CAs are ubiquitous and found in the deepest branches of life. Demonstrating evolutionary convergence, currently five CA classes have been identified, termed α, β, γ, δ, and ζ, with little to no structural homology. To date, all α- and β-CAs have been shown to be zinc metalloenzymes. The α-CAs have been the most extensively studied because of their role in human pathology and drug targeting; however, the other classes play a greater role in the global carbon cycle.1 In plants, β-CAs are required for transport and maintenance of CO2 and HCO3− concentrations for photosynthesis, and similarly, in prokaryotes they are involved in the maintenance of internal pH and CO2 and HCO3− concentrations required for biosynthetic reactions. Unlike the α-CAs, the β-CAs exhibit much greater phylogenetic diversity.3,4 Their importance in prokaryotic biology can be deduced from their widespread presence in metabolically diverse species.4 The β-CAs play an essential role in facilitating aerobic growth of microbes at low partial pressures of CO2 by providing endogenous HCO3−5−10 Additionally, β-CAs areinvolved in multiple roles such as cyanate degradation, host colonization, host survival, and growth in different organisms isms.11−13 Although β-CAs are essential for growth of microbes such as Escherichia coli,8 Corynebacterium glutamicum,9 Saccharomyces cerevisiae,14 and Helicobacter pylori,15 their full physiological role in the biosphere is still to be discovered.16

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a widely distributed environmental pathogenic bacterium that can cause diseases in animals, including humans. Especially in immune-compromised or otherwise susceptible hosts (patients with HIV, cancer, or burns), it can cause a severe infection of the heart, urinary tract, lungs, and wounds.17,18 It is also one of the major pathogenic bacteria that cause nosocomial infections.19 P. aeruginosa is found in a wide variety of habitats, so it has evolved a mechanism for thriving in environments with different concentrations of CO2. This adaptation is particularly helpful for the bacteria when they infect lungs, which have ~200-fold higher concentrations of CO2 as compared to atmospheric levels (400 ppm);20 the solubility of CO2 in water at 298 K is 55 mM.21 Because P. aeruginosa is resistant to most available antibiotics,19 β-CAs also offer a new target for antibiotic development. Lotlikar et al. have identified three genes encoding three β-CAs (psCA1–3) in P. aeruginosa PAO1.22

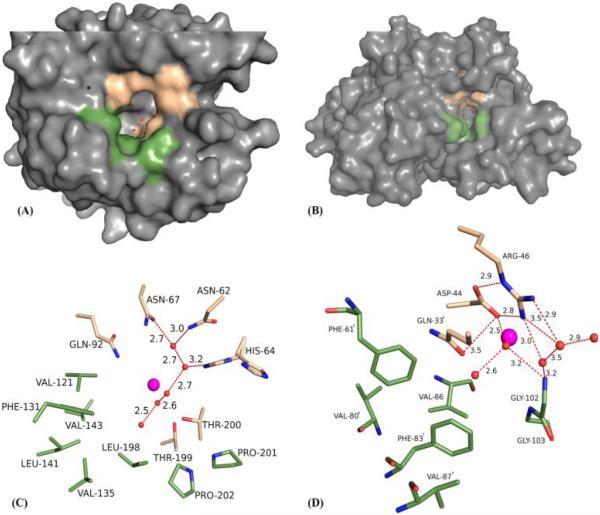

Most CAs are extremely fast enzymes that function at a rate that approaches the diffusion-controlled limit (kcat/KM ~ 108 M−1 s−1) and follow Michaelis–Menten kinetics. The overall fold and oligomeric state of the α- and β-CAs are very different. The α-CAs are mainly monomers (there are a few reported cases of dimers, e.g., hCAs IX and XII, but both of these can function as monomers) with an extended 10-strand twisted β-sheet, flanked by six or more α-helices.2,23 In contrast, the β-CAs are only functional as dimers or larger oligomeric states and have more compact structures: a β-sheet core composed of four or five strands, and four or more α-helices surrounding this core. Interestingly, the active sites of α- and β-CAs do exhibit certain architectural similarities. In both classes, the active sites are clearly divided into two regions, hydrophobic and hydrophilic (Figure 1A,B). In the α-CAs, the active site zinc is located at the base of a 15 Å deep conical cleft, coordinated by three histidines, and highly solvated (20 ordered waters in hCA II), whereas the β-CAs have a much shallower (<10 Å) active site, constructed by dimer formation; in an active configuration, the zinc is coordinated by two cysteines and a histidine and sparsely solvated (four ordered waters in psCA3) (Figure 1C,D). This implies that the mechanism of proton transfer is most likely different between the two CA classes. In α-CAs, this function is conducted by a well-ordered network of water molecules and a histidine proton shuttle residue (His64 in hCAII) (Figure 1C).24 In contrast, site-directed mutagenesis on β-CAs has led to the widely accepted view that a combination of residues are responsible for proton shuttling, and the identity of the residues differs among β-CAs.25-27 However, a unique arrangement of partially conserved amino acid residues in the active site (Asp-Arg dyad, for example) is thought to play an important role in a pH-induced catalytic switch in the opening and closing of the active site, by displacing a zinc-bound solvent molecule (ZBS) (Figure 1D). The ZBS, which can be either OH− or H2O (depending on the pH of the system),16 is the fourth ligand of the tetrahedrally coordinated zinc for both α- and β-CAs in an active state.

Figure 1.

Surface representation of (A) hCA II and (B) psCA3. Beige and green regions represent hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues of the active site, respectively. Stick representations of the active site for (C) hCA II and (D) psCA3. The active site zinc is depicted as a magenta sphere (only one active site of the psCA3 dimer is visible in this view). For all subsequent figures, residues will be as labeled, ordered waters depicted as red spheres, zinc depicted as a magenta sphere, H-bonds represented by red dashes, and distances given in angstroms.

As the CO2 substrate has no dipole moment, it is expected to bind weakly in the active site of these enzymes.28 The dissociation constant of CO2 measured for hCA II has been calculated to be 100 mM. This makes capture of the substrate technically difficult; in fact, until this study, only hCA II has been determined in complex with CO2, using CO2-pressurized cryo-cooled crystallography.28,29

Here we present the first structure of CO2 bound to a β-CA, psCA3, which has allowed a comparison of CO2 binding in two structurally disparate CAs that have undergone convergent evolution to perform the same enzymatic reaction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression, Purification, and Crystallization of psCA3

Cloning, expression, and purification were conducted as described previously.22 The recombinant gene PA4676 was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells with a His tag. The culture was grown at 37 °C in the presence of ampicillin (100 μg/mL) until it reached an OD600 of 1.0 and thereafter induced overnight with isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (100 μg/mL) for protein expression. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer [20 mM Tris, 5 mM imidazole, and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.9)] and lysed by sonication. Protein lysate was collected after centrifuging the lysed cells at 16000 rpm for 50 min and purified using His-tag column chromatography using a Sepharose column. Nonspecifically bound proteins were washed off the column using lysis buffer and wash buffer (lysis buffer with 60 mM imidazole); finally, the protein was eluted with elution buffer (lysis buffer with 300 mM imidazole). The eluted protein was then dialyzed [in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.3)] to remove imidazole and thereafter concentrated to 10 mg/mL using a 10 kDa filter. The crystallization condition of psCA3 crystals was optimized using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion technique; 500 μL of a reservoir solution containing 50% polyethylene glycol 200 and 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) was placed in vapor equilibration with a drop size of 5 μL of a reservoir solution and 5 μL of psCA3 protein. The psCA3 crystals were crystallized after 6 days and grew to approximate dimensions of 400 μm × 150 μm × 150 μm.

CO2 Binding

In order to be trapped as a substrate, CO2 was used as a pressurizing agent during the cryo-cooling process as described below. Using the capillary shielding method,30 psCA3 crystals were picked and soaked into 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7), 10% PEG 200, and a 10% glycerol cryoprotectant solution and inserted into one end of a capillary tube [inside diameter of 991 μm, wall of 25.4 μm (Advanced Polymers, Salem, NH)] to prevent crystal dehydration. The other end of the capillary tube was then filled with 4 μL of cryoprotectant to form a reservoir without touching the crystal. The cryoloop assembly was loaded into the bottom of a high-pressure tube,31 where the crystals were pressurized with 9 bar of CO2 for 10 min. The bottom of the pressure tubes were then immersed into liquid nitrogen and the crystals were cryo-cooled for about 2 min. During this time, the gas pressure was observed to drop below 1 bar as the CO2 solidified.28 The cooled crystals were then recovered from the high-pressure tubes in liquid nitrogen and transferred into a dewar for storage before data collection.31

X-ray Data Collection and Processing

A total of 360 X-ray diffraction image frames were collected at Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS), beamline F1, at a wavelength of 0.978 Å. Data were collected using the oscillation method in intervals of 1° on an ADSC Quantum 270 CCD detector (Area Detector Systems Corp.), with a crystal to detector distance of 195 mm. Indexing, integration, and scaling of X-ray diffraction data were performed using HKL2000.32 The data were scaled to a resolution of 1.6 Å, with an overall completeness and Rsym of 99.3 and 8.0%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Crystallographic Data Collection and Refinement Statistics (PDB entry 5BQ1)

| Data Collection | |

| temperature (K) | 100 |

| wavelength (Å) | 0.978 |

| space group | I222 |

| unit cell dimensions a, b, c (Å) | 71.8, 78.1, 87.7 |

| no. of reflections (theoretical, measured) | 32819, 32530 |

| resolution (Å) | 29.1–1.6 (1.65–1.60)a |

| R sym b | 0.08 (0.50) |

| I/σ (I) | 72.8 (6.1) |

| completeness (%) | 99.3 (98.3) |

| redundancy | 14.1 (10.9) |

| Final Model | |

| Rcrystc (%) | 17.3 (21.4) |

| Rfreed (%) | 19.9 (22.3) |

| no. of atomse (protein, ligand,f water) | 1675, 3 (2), 103 |

| rmsd [bond lengths (Å), angles (deg)] | 0.006, 0.99 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) (favored, allowed, outliers) |

98.5, 1.5, 0.0 |

| average B factor (Å2) [main chain, side chain, CO2 (active site), CO2 (interface), solvent] |

29.4, 34.8, 40.6, 22.4, 35.5 |

Values in parentheses represent data for the highest-resolution bin.

Rsym = Σ(|I - 〈I〉|)/Σ〈I〉.

Rcryst = (Σ|Fo| - |Fc|/Σ|Fobs|) × 100.

Rfree is calculated in same manner as Rcryst, except that it uses 5% of the reflection data omitted from refinement.

Includes alternate conformations.

The value in parentheses represents the total number of ligands bound in the whole structure.

Molecular Replacement and Structure Determination

Starting phases were calculated using molecular replacement from Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 4RXY33 with waters removed. The PHENIX package34 was used for refinement. A randomly selected 5% of the unique reflections was excluded from the refinement data set for the purpose of Rfree calculations,35 and refinements were alternated with manual refitting of the model in COOT.36

RESULTS

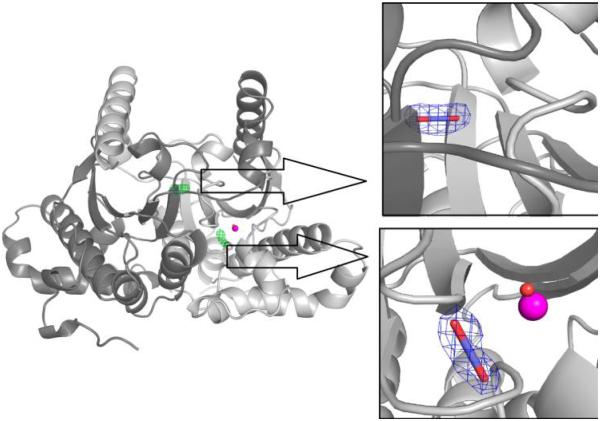

Protein psCA3 crystallized in space group I222, with unit cell dimensions of 71.8, 78.1, and 87.7 Å. The data were phased using coordinates from the recently determined psCA3 structure (PDB entry 4RXY33). The crystallographic asymmetric unit contains a psCA3 dimer. The structure was refined to a resolution of 1.6 Å, with Rcryst and Rfree values of 0.17 and 0.19, respectively; the first two residues were disordered. The crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1, and the coordinates and structure factors have been deposited as Protein Data Bank entry 5BQ1. After the initial refinement of the structure, a difference (Fo – Fc) map clearly showed electron density corresponding to three CO2 binding locations in the psCA3 dimer. As expected, two were positioned in each active site, while the third appeared unexpectedly at the dimeric interface, sandwiched between the two monomers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cartoon representation of the functional dimeric form of psCA3. The green mesh is the difference (Fo − Fc) electron density for the two CO2 binding sites, contoured at 2.0σ. The right panels show details of the CO2 binding sites. The blue mesh is the refined (2Fo − Fc) electron density after modeling building and refinement, contoured at 1.6σ.

Active Site CO2 Binding Site

CO2 was observed bound in the active site of each of the psCA3 monomers. As seen in the case of hCA II, the CO2 displaced a water, termed “deep water” that in the unbound state lies in the hydrophobic pocket and is stabilized by a short strong hydrogen bond (~2.6 Å) with the ZBS28 (Figure 3A). The CO2 resides within the hydrophobic cleft formed by Val66, Gly102, Gly103, Phe61′, Phe83′, Val87′, and Leu88′ (from the second monomer). The CO2 proximal oxygen is 2.8 Å from the ZBS, with an O-ZBS-Zn angle of 113°, thereby orienting the CO2 toward the zinc. In addition, the CO2 is further stabilized by H-bonds with the side chain oxygen of Gln33′ from the adjacent monomer (3.4 Å), and the backbone amide N of Gly103 (3.3 Å) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Hydrogen bond network in the psCA3 active site: (A) open (without CO2) and (B) with CO2. Residues are as labeled. Beige and green regions represent hydrophilic and hydrophobic residues, respectively. Note the displacement of deep water upon CO2 binding.

Dimer Interface CO2 Binding Site

Unexpectedly, a third bound CO2 was observed buried in the dimer interface, sandwiched among symmetry-paired residues Ala49, Val62, and Arg64. The oxygens of CO2 are stabilized by two paired Hbonds with the side chains of Arg64 (from each monomer), with additional stabilization by the hydrophobic residues of Ala49 and Val62 (Figure 4). On the basis of only structural observations, the dimer interface CO2 would appear to be more stable than the active site CO2, as it is completely buried with more stabilizing interactions (in terms of hydrogen bonds and buried surface area) and has a refined B factor of 22.4 Å2 compared to a value of 40.6 Å2 for the active site-bound CO2 (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Secondary binding site for another molecule of CO2 shown at the dimeric interface as (A) a cartoon and (B) sticks (close-up). The two monomers are colored yellow and cyan.

Overall Structure

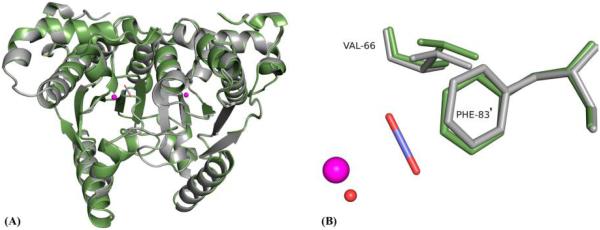

Superposition of the psCA3 structures in the unbound state (PDB entry 4RXY33) onto the complex with CO2 (reported here) showed a main chain rmsd of ~0.3 Å, implying very little structural movement upon substrate binding. However, slight structural perturbations in the side chains of Val66 and Phe81′ in the active site were observed. Val66 moved ~0.5 Å away from the catalytic zinc, possibly because of repulsion from the electronegative oxygens of CO2, and Phe81′ moved ~0.7 Å toward the active site, because of attractive hydrophobic and van der Waals forces on the carbon atom in CO2 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Superposition of unbound psCA3 (gray) and CO2-bound (green) represented as a (A) cartoon and (B) close-up sticks, showing the slight perturbation in two active site residues.

DISCUSSION

This work describes the first structure of a β-CA in complex with its substrate CO2, generated by pressurizing a crystal of psCA3 at room temperature with >5 atm of CO2, and flash-cooling it in liquid nitrogen, as described previously by our group for the α-CA, hCA II.28 The reason this method is able to capture the substrate without catalysis is that as the crystal is exposed to CO2, the pH is reduced to <6.0 and the ZBS (which would be OH− for the catalysis to occur in the hydration direction) gains a proton and becomes a water molecule. As a result of this, CA can no longer perform the CO2 to HCO3− forward reaction. Thus, the CO2 is stably bound in the active site (Figures 2 and 3).

At first, this seems like a reasonable and simple explanation for the observed CO2 binding and is the argument used when CO2 was first captured in hCA II,28 but the β-CAs class is further divided into two types, based on the structural organization of their active site configuration and catalytic pH range. Type I is active over a broad pH range, while type II is active only for an alkaline pH range. With type I, the zinc is coordinated by three residues and the ZBS [an open active site, over a large pH range (Figure 1D)], whereas in type II, the zinc is in an open state at an alkaline pH, but coordinated by four residues (Asp from the Asp-Arg dyad, in a closed state), at low pH.37,38

The type II βCAs have been shown to “switch” from an active (R) to an inactive (T) state at lower pH.18 Interestingly, the β-CA psCA3 used in this study has been previously shown to be type II; hence, at the pH of this study, the Asp-Arg dyad should have switched its conformation to the closed state and displaced the ZBS, thereby eliminating the CO2 binding site.22 However, in unpublished studies, we soaked crystals of psCA3 (initially grown at pH 7) in solutions at pH <6, and they never underwent the pH-induced structural switch. Therefore, it can be argued that crystal packing constraints of psCA3 may inhibit this conformational switch; in another packing configuration, the Asp-Arg dyad might be induced to transform to the T state. These studies are now ongoing. A direct H-bond between CO2 and Gln33′ is particularly interesting as it supports the previously reported and hypothesized importance of Gln33′ (or its equivalent in β-CAs from other organisms) in stabilization of the transition state during the conversion of CO2 to HCO3−. This finding is a direct corroboration of the proposed role of Gln33′ as suggested by site-directed mutagenesis.39

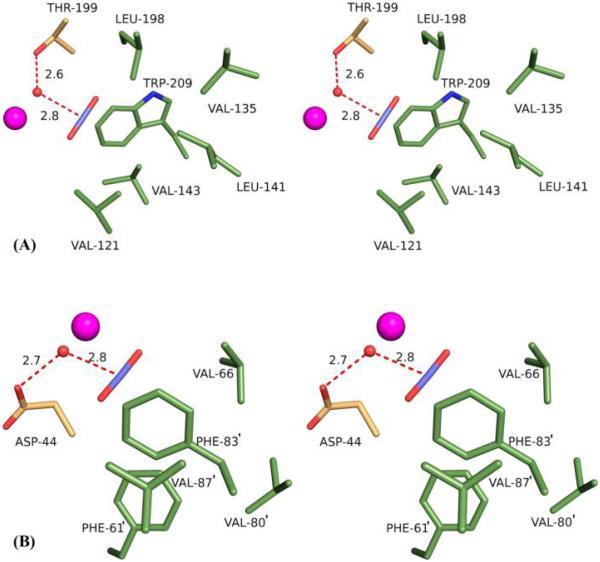

Despite being disparate and evolutionarily distinct structures, the CO2 active binding sites for psCA3 and hCA II are remarkably similar. In both, the CO2 is located in a hydrophobic pocket defined by five residues: in psCA3, the residues are Phe61′, Val66′, Phe83′, Val87′, and Leu88′, while in hCA II, they are Val121, Val135, Leu141, Val143, and Trp209, with some differences in amino acid type and spatial arrangement. Both have an aromatic amino acid (Phe83′ in psCA3 and Trp209 in hCA II) as the assembly core of the hydrophobic cluster cavity. In addition, even though the active site of psCA3 is much shallower and has fewer waters than hCA II, it is noteworthy that the CO2 buries 129.7 Å2 (~87% of its total surface area), comparable to that in hCA II (128.1 Å2). These surface area calculations were performed using PDBePISA40 (Figure 6). Also, relative to the zinc, the orientation of the CO2 is almost identical, with the CO2 central carbon aligned and distanced 2.8 Å from the ZBS, presumably in readiness for nucleophilic attack. The ZBS is stabilized by a H-bond with Thr199 in HCA II and Asp44 in psCA3 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Cross-eyed stereoview of CO2 in the active site of (A) hCA II and (B) psCA3. Residues are as labeled.

Unexpected was the discovery of an additional CO2 binding site at the dimer interface of psCA3, where the CO2 is completely surface “inaccessible” and stabilized by four H-bonds. Of course, in the case of hCA II, which functions as a monomer, this interface does not exist. Hence, this dimer binding site begs the question of how the CO2 binds and whether it has implications for enzyme function, as the active site only forms when psCA3 is a dimer (Figure 1B,D).

It is known that β-CAs, unlike α-CAs, exhibit allostery.16 Previous studies have shown this interface pocket to be a promiscuous site for a variety of ligands, including bicarbonate, sulfate, and phosphate ions. Also, the existence of a noncatalytic bicarbonate ion binding site in Haemophilus influenzae β-CA (HICA, PDB entry 2A8D38) and E. coli β-CA (ECCA, PDB entry 1I6P41) that is characterized by a Trp39-Arg64-Tyr181 (HICA numbering) triad has been identified. In these type II β-CAs, binding of a bicarbonate ion in this allosteric site relocates the side chain of Val47 (HICA numbering) and causes the reorganization of the 44−48 loop; the Asp44-Arg46 dyad is also disrupted. Interestingly, psCA3 also contains this Trp39-Arg64-Tyr182 triad (psCA3 numbering). Though bicarbonate was not found bound in this potential allosteric binding site in psCA3, the CO2 molecule at the dimer interface was only ~6 Å from this site. The CO2 at this site is completely buried, and the only way this molecule could have entered this site seems to be due to the protein dynamics and molecular “breathing”. Possibly, under alkaline pH conditions, CO2 would be converted into HCO3− and bind in the allosteric site; it might then adopt the closed active site configuration as its 44−48 loop underwent reorganization. In addition to HCO3−, other ions such as sulfate,38 phosphate,39 and chloride42 have also been reported to be bound at this site. Hence, we propose that this site may have a biochemical, structural, and physiological role to play and is not just an experimental artifact caused by exposure to pressurized CO2, but it could also just be a highly promiscuous site that can potentially bind many different small molecules. Further experimental studies would be needed to answer this question.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff at CHESS and MacCHESS (Cornell University) for their support and beamtime. CHESS is supported by National Science Foundation Grant DMR-1332208, and MacCHESS is supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM-103485. This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle LLC under DOE Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 with the U.S. Department of Energy. The publisher, by accepting the article, acknowledges that the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for the purposes of the U.S. Government.

Funding

This work has been funded by a Shull Fellowship awarded to M.A. at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and National Institutes of Health Grant GM25154.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CA

carbonic anhydrase

- ZBS

zinc-bound solvent

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- rmsd

root-mean-square deviation

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Frost SC, McKenna R. Carbonic Anhydrase: Mechanism, Regulation, Links to Disease, and Industrial Applications. Springer Science & Business Media; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Aggarwal M, Boone CD, Kondeti B, McKenna R. Structural annotation of human carbonic anhydrases. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013;28:267–277. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2012.737323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Smith KS, Jakubzick C, Whittam TS, Ferry JG. Carbonic anhydrase is an ancient enzyme widespread in prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:15184–15189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Smith KS, Ferry JG. Prokaryotic carbonic anhydrases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000;24:335–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Fukuzawa H, Suzuki E, Komukai Y, Miyachi S. A gene homologous to chloroplast carbonic anhydrase (icfA) is essential to photosynthetic carbon dioxide fixation by Synechococcus PCC7942. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:4437–4441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Guilloton MB, Lamblin AF, Kozliak EI, Gerami-Nejad M, Tu C, Silverman D, Anderson PM, Fuchs JA. A physiological role for cyanate-induced carbonic anhydrase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:1443–1451. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1443-1451.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kusian B, Sültemeyer D, Bowien B. Carbonic anhydrase is essential for growth of Ralstonia eutropha at ambient CO(2) concentrations. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:5018–5026. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.18.5018-5026.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Merlin C, Masters M, McAteer S, Coulson A. Why is carbonic anhydrase essential to Escherichia coli? J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:6415–6424. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.21.6415-6424.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Mitsuhashi S, Ohnishi J, Hayashi M, Ikeda M. A gene homologous to beta-type carbonic anhydrase is essential for the growth of Corynebacterium glutamicum under atmospheric conditions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004;63:592–601. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Burghout P, Cron LE, Gradstedt H, Quintero B, Simonetti E, Bijlsma JJE, Bootsma HJ, Hermans PWM. Carbonic anhydrase is essential for Streptococcus pneumoniae growth in environmental ambient air. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:4054–4062. doi: 10.1128/JB.00151-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Valdivia RH, Falkow S. Fluorescence-based isolation of bacterial genes expressed within host cells. Science. 1997;277:2007–2011. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Bury-Moné S, Mendz GL, Ball GE, Thibonnier M, Stingl K, Ecobichon C, Avé P, Huerre M, Labigne A, Thiberge J-M, De Reuse H. Roles of alpha and beta carbonic anhydrases of Helicobacter pylori in the urease-dependent response to acidity and in colonization of the murine gastric mucosa. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:497–509. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00993-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Guilloton MB, Korte JJ, Lamblin AF, Fuchs JA, Anderson PM. Carbonic anhydrase in Escherichia coli. A product of the cyn operon. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:3731–3734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Götz R, Gnann A, Zimmermann FK. Deletion of the carbonic anhydrase-like gene NCE103 of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae causes an oxygen-sensitive growth defect. Yeast. 1999;15:855–864. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199907)15:10A<855::AID-YEA425>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Clark D, Rowlett RS, Coleman JR, Klessig DF. Complementation of the yeast deletion mutant DeltaNCE103 by members of the beta class of carbonic anhydrases is dependent on carbonic anhydrase activity rather than on antioxidant activity. Biochem. J. 2004;379:609–615. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Rowlett RS. Structure and catalytic mechanism of the beta-carbonic anhydrases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2010;1804:362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Richard P, Le Floch R, Chamoux C, Pannier M, Espaze E, Richt H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa outbreak in a burn unit: role of antimicrobials in the emergence of multiply resistant strains. J. Infect. Dis. 1994;170:377–383. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kalai S, Achour W, Abdeladhim A, Bejaoui M, Ben Hassen A. [Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in immunocompromised patients: antimicrobial resistance, serotyping, and molecular typing] Médecine Mal. Infect. 2005;35:530–535. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Mesaros N, Nordmann P, Plésiat P, Roussel-Delvallez M, Van Eldere J, Glupczynski Y, Van Laethem Y, Jacobs F, Lebecque P, Malfroot A, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance and therapeutic options at the turn of the new millennium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2007;13:560–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Rehm BHA. Pseudomonas: Model Organism, Pathogen, Cell Factory. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Diamond LW, Akinfiev NN. Solubility of CO2 in water from − 1.5 to 100 °C and from 0.1 to 100 MPa: evaluation of literature data and thermodynamic modelling. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2003;208:265–290. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lotlikar SR, Hnatusko S, Dickenson NE, Choudhari SP, Picking WL, Patrauchan MA. Three functional β-carbonic anhydrases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1: role in survival in ambient air. Microbiology. 2013;159:1748–1759. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.066357-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Alterio V, Hilvo M, Di Fiore A, Supuran CT, Pan P, Parkkila S, Scaloni A, Pastorek J, Pastorekova S, Pedone C, Scozzafava A, Monti SM, De Simone G. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of the tumor-associated human carbonic anhydrase IX. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:16233–16238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908301106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Aggarwal M, Kondeti B, Tu C, Maupin CM, Silverman DN, McKenna R. Structural insight into activity enhancement and inhibition of H64A carbonic anhydrase II by imidazoles. IUCrJ. 2014;1:129–135. doi: 10.1107/S2052252514004096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Smith KS, Ingram-Smith C, Ferry JG. Roles of the conserved aspartate and arginine in the catalytic mechanism of an archaeal beta-class carbonic anhydrase. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:4240–4245. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.15.4240-4245.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rowlett RS, Tu C, McKay MM, Preiss JR, Loomis RJ, Hicks KA, Marchione RJ, Strong JA, Donovan GS, Chamberlin JE. Kinetic characterization of wild-type and proton transfer-impaired variants of beta-carbonic anhydrase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;404:197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Björkbacka H, Johansson IM, Forsman C. Possible roles for His 208 in the active-site region of chloroplast carbonic anhydrase from Pisum sativum. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;361:17–24. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Domsic JF, Avvaru BS, Kim CU, Gruner SM, Agbandje-McKenna M, Silverman DN, McKenna R. Entrapment of carbon dioxide in the active site of carbonic anhydrase II. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:30766–30771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805353200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Sjöblom B, Polentarutti M, Djinovic-Carugo K. Structural study of X-ray induced activation of carbonic anhydrase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:10609–10613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904184106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kim CU, Wierman JL, Gillilan R, Lima E, Gruner SM. A high-pressure cryocooling method for protein crystals and biological samples with reduced background X-ray scatter. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2013;46:234–241. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812045013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kim CU, Kapfer R, Gruner SM. High-pressure cooling of protein crystals without cryoprotectants. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2005;61:881–890. doi: 10.1107/S090744490500836X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–26. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Pinard MA, Lotlikar SR, Boone CD, Vullo D, Supuran CT, Patrauchan MA, McKenna R. Structure and inhibition studies of a type II beta-carbonic anhydrase psCA3 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23(15):4831–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Brünger AT. Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature. 1992;355:472–475. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kimber MS, Pai EF. The active site architecture of Pisum sativum beta-carbonic anhydrase is a mirror image of that of alpha-carbonic anhydrases. EMBO J. 2000;19:1407–1418. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Cronk JD, Rowlett RS, Zhang KYJ, Tu C, Endrizzi JA, Lee J, Gareiss PC, Preiss JR. Identification of a novel noncatalytic bicarbonate binding site in eubacterial beta-carbonic anhydrase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4351–4361. doi: 10.1021/bi052272q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Rowlett RS, Tu C, Lee J, Herman AG, Chapnick DA, Shah SH, Gareiss PC. Allosteric site variants of Haemophilus influenzae beta-carbonic anhydrase. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6146–6156. doi: 10.1021/bi900663h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Cronk JD, Endrizzi JA, Cronk MR, O’neill JW, Zhang KY. Crystal structure of E. coli beta-carbonic anhydrase, an enzyme with an unusual pH-dependent activity. Protein Sci. 2001;10:911–922. doi: 10.1110/ps.46301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Huang S, Hainzl T, Grundström C, Forsman C, Samuelsson G, Sauer-Eriksson AE. Structural studies of β-carbonic anhydrase from the green alga Coccomyxa: inhibitor c complexes with anions and acetazolamide. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]