Abstract

Catecholamines, which include the neurotransmitters dopamine and noradrenaline, are known modulators of sensorimotor function, reproduction, and sexually motivated behaviors across vertebrates, including vocal-acoustic communication. Recently, we demonstrated robust catecholaminergic (CA) innervation throughout the vocal-motor system in the plainfin midshipman fish, Porichtys notatus, a seasonal breeding marine teleost that produces vocal signals for social communication. There are two distinct male reproductive morphs in this species: Type I males establish nests and court females with a long duration advertisement call, while type II males sneak-spawn to steal fertilizations from type I males. Like females, type II males can only produce brief, agonistic, grunt-type vocalizations. Here, we tested the hypothesis that intrasexual differences in the numbers of CA neurons and their fiber innervation patterns throughout the vocal-motor pathway may provide neural substrates underlying divergence in reproductive behavior between morphs. We employed immunofluorescence (-ir) histochemistry to measure tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine synthesis) neuron numbers in several forebrain and hindbrain nuclei as well as TH-ir fiber innervation throughout the vocal pathway in type I and type II males collected from nests during the summer reproductive season. After controlling for differences in body size, only one group of CA neurons displayed an unequivocal difference between male morphs: the extraventricular vagal-associated TH-ir neurons, located just lateral to the dimorphic vocal motor nucleus (VMN), were significantly greater in number in type II males. In addition, type II males exhibited greater TH-ir fiber density within the VMN and greater numbers of TH-ir varicosities with putative contacts on vocal motor neurons. This strong inverse relationship between the predominant vocal morphotype and CA innervation of vocal motor neurons suggests catecholamines may function to inhibit vocal output in midshipman. These findings support catecholamines as direct modulators of vocal behavior and differential CA input appears reflective of social and reproductive behavioral divergence between male midshipman morphs.

Keywords: teleost, dopamine, noradrenaline, catecholamine, vocal motor, alternative reproductive tactics, teleost, posterior tuberculum, locus coeruleus, preoptic area

INTRODUCTION

Batrachoidid fishes (midshipman and toadfishes) possess a straightforward repertoire of vocalizations complemented by vocal circuitry that is evolutionarily conserved [Goodson and Bass, 2002; Bass et al., 2008; Bass, 2014]. The plainfin midshipman fish, Porichthys notatus, is a well-studied neuroethological model for investigating the neural and hormonal mechanisms underlying vertebrate vocal behavior. This is due to the fact that the production and recognition of social-acoustic signals is critical to reproduction in this species. In the summer breeding season at sites along the western coast of North America, males vocally court females from under rocky intertidal nests and females localize males by following their call. There are two distinct reproductive male morphs that follow divergent developmental trajectories with corresponding alternative reproductive tactics: type I males defend a nest and vocally court females while type II males do neither but instead sneak spawn in competition with type I males [Brantley and Bass, 1994; Bass, 1996]. Type II males also reach sexual maturity earlier and share a multitude of biochemical, hormonal, morphological, and behavioral similarities to females that are different from type I males [Bass et al., 1996; Goodson and Bass, 2000a; Bass and Forlano, 2008; Remage-Healey and Bass, 2007; Arterbery et al., 2010a, 2010b].

Batrachoidid fishes possess an expansive vocal-motor network, including a rhythmically firing vocal pattern generator (VPG), located in the caudal hindbrain-rostral spinal cord [Chagnaud et al., 2011; Bass et al., 2008; Bass, 2014]. Preoptic and hypothalamic ventral (vT) and anterior (AT) tuberal nuclei, which are reciprocally connected to the ventral telencephalon, project to the midbrain periaqueductal gray (PAG) and paratoral tegmentum, (PTT), which in turn innervate the vocal prepacemaker nucleus (VPP), the most rostral part of the VPG [Goodson and Bass, 2002; Kittelberger and Bass, 2013]. The VPP encodes duration of the call, while its efferent target, vocal pacemaker neurons, encode call frequency (pul se repetition rate) that is delivered by the vocal motor (VMN) nucleus [Chagnaud et al., 2011]. VMN axons exit the brain by way of occipital nerve roots to sound-producing vocal muscle attached to the sides of the swim bladder [Bass et al., 1994]. Type I males are the only morphotype capable of producing agonistic growls and the long duration advertisement call (“hum”) that is attractive to the female, whereas type II males and females can only produce short-duration agonistic grunts [Bass, 1996; Bass and McKibben, 2003; McIver et al., 2014]. Well-established sexual polymorphisms in the midshipman hindbrain-spinal vocal circuitry are related to divergence of male vocal behavior. Type I males have larger vocal muscles in addition to a larger volume VMN with larger motor neurons compared to type II males and females [Bass and Baker, 1990; Bass et al., 1996; Bass and Forlano, 2008]. Despite their relatively small body size and minimal, female-like vocal muscle, type II males possess a testes to body weight ratio that is nine times greater than type I males [Bass, 1996].

Like songbirds [Appeltants et al., 2001, 2002a, 2002b; Mello et al., 1998; Castelino and Ball, 2005; Hara et al., 2007], the vocal-motor pathway in midshipman receives significant catecholaminergic (CA) input [Forlano et al., 2014; Goebrecht et al., 2014]. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine synthesis, can be used as a marker for neurons that synthesize and release the neurotransmitters dopamine (DA) and noradrenaline (NA), known modulators of motivated vertebrate sociosexual behaviors [O’Connell and Hofmann, 2011; Riters, 2012; Kelly and Goodson, 2015]. Recent neuroanatomical studies support a role for catecholamines as modulators of social-acoustic behavior in midshipman. Using cFos-ir as a marker for neural activation, both TH immunoreactive (-ir) neurons in the diencephalic periventricular posterior tuberculum (TPp), known to be dopaminergic [Tay et al., 2011; Yamamoto and Vernier, 2011], and the noradrenergic locus coeruleus (LC) of type I males are preferentially responsive to conspecific advertisement calls compared to ambient noise [Petersen et al., 2013]. There is also seasonal variation in the density of TH-ir fiber innervation throughout the central and peripheral auditory system of female midshipman related to reproductive state [Forlano et al., 2015]. However, relationships between TH-ir and circuitry underlying alternative male reproductive behavior are unexplored. Brain CA nuclei and fiber densities are known to be regulated by steroid hormones [Wilczynski et al., 2003; LeBlanc et al., 2007; Kabelik et al., 2011; Matragrano et al., 2013; Barth et al., 2015], and forebrain dopaminergic neurons in midshipman are located in areas replete with androgen and estrogen receptors and aromatase (estrogen synthase) [Forlano et al., 2001, 2005, 2010, 2014]. Importantly, steroid hormone profiles, estrogen receptor expression, as well as aromatase activity and expression are different between male morphs [Brantley et al., 1993; Schlinger et al., 1999; Forlano and Bass, 2005; Fergus and Bass 2013], which may regulate morph differences in CA neuron number and/or their innervation patterns.

Here, we tested the hypothesis that numbers of CA neurons in key forebrain and hindbrain nuclei and CA fiber innervation patterns throughout hypothalamic, midbrain, and hindbrain components of the midshipman vocal-motor pathway would show intrasexual differences between male midshipman reproductive morphs. Since our measurements included only TH-ir somata and fibers and not specific CA receptor subtypes (which are known to generate diverse effects on physiology) [e.g., Ericsson et al. 2013; Devries et al. 2015], we purposefully did not predict directional differences between morphs a priori. Our results provide evidence that intrasexual differences in numbers of specific CA neurons and CA fiber innervation within the vocal motor system may provide neural substrates underlying alternative reproductive tactics in midshipman males within the summer reproductive season.

METHODS

Animals

Nineteen plainfin midshipman fish (10 type I males and 9 type II males) were collected from intertidal nesting sites along Tomales Bay, California during the summer reproductive season. Animals were held in running seawater tanks at the University of California Bodega Marine Laboratory (BML) prior to sacrifice and tissue collection within 48 hrs of capture. Only type I males that had no eggs or fresh eggs in their nest were collected. This reflects males early in the reproductive season that are actively courting females at night. Once type I male nests are filled with developing embryos, they cease courtship and are fully parental with a significant decline in circulating androgens [Knapp et al., 1999; Sisneros et al., 2004, 2009]. All protocols were in agreement with the guidelines set forth by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the CUNY Brooklyn College and the University of California. Animals were anesthetized by immersion in seawater mixed with 0.025% benzocaine, weighed with a scale (Sartorius Mechatronics TE612, Göttingen, Germany), measured with a metric ruler, and perfused with ice-cold teleost Ringer’s solution followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). Testes were removed, weighed and gonadosomatic index (GSI) was calculated by ratio of testes mass to body mass minus testes mass × 100. Brains were removed, postfixed for one hour, and transferred to 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.2). After incubation in 0.1 M PB with 30% sucrose for 48 hrs, brains were sectioned in the coronal plane at 25 µm with a cryostat and collected in two series onto positively charged slides. One series from each animal was used for this study and were stored at −80°C until processed for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as follows: 20 min in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2), 1 hr in bl ocking solution (PBS + 10% donkey serum (DS) + 0.3% Triton-X-100), 18 hrs at room temperature in anti-TH antibody raised in mouse (Millipore, Temecula, CA) diluted 1:1000 in the aforementioned blocking solution, 5 × 10 min rinses in PBS + 0.5% DS, 2 hr in anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Flour 568 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) diluted 1:200 in the aforementioned blocking solution. Sections were extensively washed in PBS, after which a green fluorescent Nissl stain (NeuroTrace 500/525; Life Technologies) was diluted 1:200 in PBS, applied to the sections and allowed to incubate for 20 min prior to being washed 4 × 10 min with PBS. Slides were coverslipped with Prolong Gold containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole nuclear stain (DAPI; Life Technologies), allowed to cure in the dark at room temperature for approximately 48 hr, then sealed with nail polish and stored at 4°C.

Image Acquisition and Anatomy

Images were acquired on an Olympus BX61 epifluorescence compound microscope using MetaMorph imaging and processing software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Each nucleus was imaged with a 20× objective at a constant exposure time and light level. Each image was comprised of consecutively taken photomicrographs using Texas Red, GFP (where appropriate) and DAPI filter sets (Chroma, Bellow Falls, VT) within a z-stack (sequential acquisition of a specified area with the focused position varied by a constant step ranging around a central plane) containing 5–9 levels, each with a step of 1 µm. These photomicrographs were then combined into a single projected image in MetaMorph using the Stack Arithmetic function and nuclear boundaries were drawn post-acquisition using DAPI to define cytoarchitecture. Sampling strategy was determined per region to account for intrinsic variation in size between nuclei. In the case of tissue loss or damage, the opposite side of the brain was used (for unilateral sampling), or the section was omitted. Experimenter was blind t o the treatment conditions of all slides analyzed.

Cell counts

Numbers of TH-ir neurons were counted in the anterior parvocellular preoptic nucleus (PPa), TPp, and LC, which provide both local and widespread CA projections throughout the teleost brain. We also quantified TH-ir neurons associated with vagal lobes (XL) and area postrema (AP), which run parallel with and appear to provide significant CA input into the VMN [Forlano et al., 2014; Goebrecht et al., 2014]. Individual TH-ir neurons were counted only if the cell’s perimeter was clearly outlined with a labeled neurite in addition to having a nucleus that exhibited colocalization with DAPI. In each animal, total numbers of TH-ir neurons were manually counted in each brain area of interest. In the event that the total cell number in a given nucleus shared a significant relationship with body size (see Statistics), the total number of TH-ir neurons for each subject was divided by its corresponding standard length (SL) to obtain a corrected measure of neurons per cm body length. This method is in line with what has been done in previous studies examining brain cells in sexually polymorphic fish, and has provided novel insight into the neural correlates of alternative reproductive tactics within males of the same species [Grober et al., 1994; Foran and Bass, 1998; Miranda et al., 2003].

Sampling of the PPa was done as previously described [Forlano et al., 2015], starting rostral to the horizontal commissure, with the appearance of parvocellular TH-ir cells clustered ventrolateral to the midline in the caudal-most aspect of the nucleus and continued serially in the rostral direction until their disappearance, just rostral to the anterior commissure. A single image comprised of a z-stack of 9 levels was taken unilaterally of TH-ir neurons for an average of 10 (± 2.5 SD) consecutive sections per animal. There was no difference in the number of sections between groups (unpaired t-test, p > 0.1).

Sampling of the TPp was done as previously described [Petersen et al. 2013; Forlano et al. 2015], and began caudally with the appearance of dense clusters of large, pear-shaped TH-ir neurons lying medial to the medial forebrain bundle (MFB), extending ventrolaterally along the lateral edge of the paraventricular organ (PVO). Up to three images with a z-stack of 9 levels were necessary to capture all TH-ir neurons per section and photomicrographs were aligned prior to analysis to avoid overlap. The TPp was analyzed serially for an average of 7.5 (± 1.7 SD) sections in the caudal-to-rostral direction until the disappearance of large, pear-shaped TH-ir cells adjacent to the midline. The number of sections analyzed was not different between groups (unpaired t-test, p > 0.1).

The LC was identified by the presence of TH-ir neurons dorsolateral to the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) in the isthmal region between the hindbrain and midbrain. Sampling was done as previously described [Petersen et al., 2013; Forlano et al., 2015], and began with the bilateral appearance of TH-ir neurons, continuing serially in the caudal-to-rostral direction for an average of 9.3 (± 2.4 SD) sections per animal until their disappearance. A single image with a z-stack of 7 levels was taken of TH-ir neurons unilaterally per section. Type I males had more sections in this area of the brain (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0183).

Sampling of the vagal-associated TH-ir neurons started at the caudal-most extent of the VMN where large, extraventricular, fusiform bipolar TH-ir neurons first appear lateral to the dorsal half of the VMN throughout its extent. Sampling continued in the rostral direction into the XL where small, round, monopolar TH-ir neurons are found near the ventricle [see Forlano et al., 2014 and Results]. In total, an average of 34.8 (± 10.8 SD) sections were sampled to encompass all vagal-associated TH-ir neurons. With the exception of the rostral extent of the XL where it was necessary to take two images to capture all visible TH-ir neurons, a single image of each section was taken unilaterally with a z-stack of 9 levels. Type I males had more sections throughout this area of the brain (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0032).

The AP was located by the presence of TH-ir neurons within a distinct cytoarchitectural boundary resembling a triangular wedge at the midline in the dorsal-most part of the section. Sampling began with the appearance of TH-ir neurons within the wedge and continued serially from the caudal-to-rostral direction for an average of 10.1 (± 3.3 SD) sections per animal until their disappearance. A single image of each section was taken with a z-stack of 9 levels. Type I males had more sections throughout this area of the brain (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0012).

Fiber analysis

TH-ir fiber innervation was quantified by segmenting TH-ir signal of interest in each image using the Inclusive Threshold feature of MetaMorph. The threshold level for each image was set manually due to subtle variation in background staining. Threshold levels were determined so that pixels selected by MetaMorph were in conformance with what the blind observer deemed to be TH-ir (e.g., distinct labeling above unlabeled structures in the same section). TH-ir fibers covering the area defined as region of interest (ROI) were subsequently measured using the Region Statistics feature to obtain data on total TH-ir area (µm2), total area sampled (µm2), average intensity (intensity independent of area), and integrated (total) intensity (TH-ir area divided by a 0.3225 µm2 distance calibration constant and multiplied by average intensity) per section in the hypothalamus and midbrain, and per fractional area in the VMN. This approach has been similarly employed by other studies examining TH-ir fiber plasticity in songbirds and midshipman [LeBlanc et al., 2007; Matragrano et al., 2011; Forlano et al., 2015].

A measure of percent thresholded area (total TH-ir area ÷ total area sampled) was used to compare fiber innervation of the AT, vT, PAG, and PTT in order to control for potential confounds of body size on density measurements. The AT is located in the ventral hypothalamus, rostral to the dorsal periventricular hypothalamus (Hd) and dorsal to the lateral hypothalamus (LH). The AT was sampled as previously described [Petersen et al., 2013; Forlano et al., 2015] for an average of 5.8 (± 1 SD) consecutive sections were imaged unilaterally on the left side of the brain using a z-stack of 5 levels and TH-ir fiber innervation was quantified within the field of view (143,139 µm2). The vT was sampled unilaterally as previously described [Petersen et al., 2013] in serial sections on the left side of the brain starting at the level of the horizontal commissure. A ROI was drawn around vT in the DAPI channel and transferred to the Texas Red channel where TH-ir fiber density was quantified. On average, 3.6 (± 1 SD) sections were used per animal. The number of sections analyzed throughout the AT and vT did not differ between groups (unpaired t-test, p > 0.5 in both cases).

Sampling of the PAG and PTT started at the caudal division lying lateral to the granule layer of the valvula and dorsal to the nucleus lateralis valvulae [Goodson and Bass 2002], and continued serially toward the rostral division of the nucleus. Images were taken every other section with a z-stack of 5 levels for an average of 7.8 (± 1.6 SD) sections per animal through the PAG and 5.8 (± 1.5 SD) through the PTT. In some cases, both the PAG and PTT could be captured in one image; however, it was necessary to take separate images of the PTT during the transition between the caudal and rostral divisions of the PAG. Two separate ROIs were drawn in the DAPI channel and then transferred to the Texas Red channel where TH-ir fiber innervation was quantified. The PAG appears as a dense layer of cell bodies ventral to the cerebral aqueduct and medial to the periventricular cell layer (Pe) of the torus semicircularis (TS) [Goodson and Bass, 2002; Kittelberger and Bass, 2013]. One ROI was drawn around the layer of cells comprising the PAG, lying ventral to the cerebral aqueduct. The other was drawn around the PTT, with the medial extent defined by the dorsomedial cell layer of the PAG, and the thin band of cells comprising the periventricular cell layer of the torus defined the lateral extent [Goodson and Bass, 2002; Kittelberger and Bass, 2013]. The number of sections analyzed throughout the PAG and PTT did not differ between groups (unpaired t-test, p > 0.2 in both cases).

For the VMN, images were taken with a 20× objective every other section using a z-stack of 5 levels for a total of eight sections per animal spanning toward the rostral extent of the nucleus, with sampling ending at the point where the VMN decreased in size and did not take up the entire field of view. To account for the intrasexual dimorphism in the size of VMN [Bass and Marchaterre, 1989; Bass et al., 1996], a design-based stereological approach was taken by overlaying a five by five rectangular grid on each image and subsampling a constant fractional area (86.11 × 66.11 µm or 5,692.7 µm2) in a random systematic manner five times within the bounds of the nucleus in each section for a total of 40 fractional measurements per animal. In addition to the density of TH-ir fibers per unit area, the area of overlap between TH-ir fibers and fluorescent Nissl-stained motor neurons within the VMN was quantified using MetaMorph’s Measure Colcalization function.

In order to quantify the number of putative TH-ir contacts on individual motor neurons within the VMN, images were taken using a 60× oil-immersion objective from two of the aforementioned fractional samples per section. For this level of analysis, z-stacks were defined by setting an upper and lower limit based on the approximate upper and lower boundaries of each motor neuron and were sampled in 1 µm steps. Fifteen individual motor neurons were sampled per animal using a random systematic method. A region was manually traced around each projected image of a motor neuron and subsequently di lated using a circular morphology filter with a constant diameter of 2.5 µm to estimate putative TH-ir contacts or CA release sites in very close proximity of the motor neuron soma. This was done because CA neuromodulatory signaling is not only confined to the synapse, and often occurs extra-synaptically in a paracrine manner [McLean and Fetcho, 2004b; Descarries et al., 2008]. Each region was then overlaid onto the corresponding Texas Red image, and TH-ir fibers making putative contacts within the morphologically defined boundaries were segmented using the Integrated Morphometric Analysis feature in MetaMorph to obtain a measure of numbers of putative TH-ir contacts per motor neuron.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism version 6 (La Jolla, CA). Pearson correlations were used to examine the relationship between total TH-ir cell number and SL in each nucleus of interest in order to assess the need to control for differences in body size. A series of unpaired Student’s t-tests were utilized at the α = 0.05 significance level to compare TH-ir neuronal and fiber density data in each brain area of interest. A Welch-corrected t-test was used if the result of an F-test showed heterogeneity of variance between groups. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare body mass and GSI between morphs, as the data did not meet Gaussian assumptions. As a way of determining the level of confidence in estimates of total TH-ir cell number, an animal was excluded from analysis if it was missing more than than half the average number of sections sampled per animal for a given brain area. In general, individual animals missing more than half the average number of sections in a region of interest possessed far fewer neurons relative to the rest of the dataset. Statistics are reported as (mean ± standard error, SE) unless otherwise noted.

RESULTS

Morphometrics

Male morphs were easily distinguishable based on behavioral observations in the field, body size data, and gonad morphology as previously reported [Bass and Baker, 1990; Bass, 1992; Brantley and Bass, 1994; Bass et al., 1996]. As expected, type I males were significantly larger in SL (t17 = 10.06, p < 0.0001) and body mass (U = 0, p < 0.0001), while type II males had a significantly greater GSI (U = 0, p < 0.0001) (Table 1). Type I males had significantly more sections throughout the LC, vagal nuclei, and AP (see Methods); however, there were no differences in the average number of TH-ir cells per section between morphs and significant differences became apparent after adjusting total cell number for body size (Table 2). While this approach to controlling for differences in body size between treatment groups is not ideal (ANCOVA is the most appropriate), our data failed to meet the first assumption of that analysis (independence of the covariate and treatment effect) due to the dramatic difference in body size between morphs (Table 1). As such, we utilized Pearson correlations to determine whether or not total TH-ir cell number in each brain area of interest varied significantly with body size. It is important to note that the ratio (total TH-ir neurons divided by SL) will only account for differences in body size if the relationship between the numerator and denominator is a significantly linear relationship [Curran-Everett 2013]. If this condition is not met, the computed ratio will misrepresent the true relationship between total TH-ir cell number and SL, biasing normalized values toward the much smaller type II males. Therefore, we only report normalized TH-ir cell data in nuclei where total TH-ir cell number was significantly correlated to SL.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for morphometric data

| Morphotype | Type I male, N=10 | Type II male, N=9 |

|---|---|---|

| Range (mean ± SD) | Range (mean ± SD) | |

| Standard length (cm) | *14.4–19.9 (16.7 ± 1.8) | 7.7–11 (9.5 ± 1.2) |

| Body mass (g) | *39.2–101.4 (62.7 ± 21.3) | 5.3–16.3 (11.1 ± 4.2) |

| Gonad weight (g) | 0.3–1.6 (0.9 ± 0.4) | 0.3–1.8 (1 ± 0.6) |

| GSI (%) | 0.7–2.4 (1.5 ± 0.5) | *4.1–19.51a (10 ± 5.3) |

Indicates significant difference between morphs (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Summary statistics (mean ± SD) for TH-ir cell count data

| ROI | Morphotype | Total cells | No. sections | Cells / section | Cells / SL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPa | TI (N=9) | 115.2 ± 45.5 | 10.8 ± 2.6 | 11.2 ± 4 | † |

| TII (N=7) | 98 ± 19.7 | 8.9 ± 2 | 11.5 ± 3.3 | † | |

| TPp | TI (N=9) | 289.3 ± 97.2 | 8.1 ± 1.8 | 36.1 ± 10.4 | † |

| TII (N=8) | 225.1 ± 46.7 | 6.9 ± 1.4 | 34.3 ± 12.3 | † | |

| LC | TI (N=9) | 44.2 ± 5.6 | *10.6 ± 2.3 | 4.3 ± 0.9 | † |

| TII (N=8) | 37.6 ± 8.9 | 7.9 ± 1.8 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | † | |

| Vagalpara | TI (N=9) | 11 ± 6.2 | 7.3 ± 4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | † |

| TII (N=9) | 12.1 ± 5.2 | 7 ± 1.9 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | † | |

| Vagalextra | TI (N=9) | 133.4 ± 29.8 | *41.7 ± 9.7 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 7.9 ± 1.9 |

| TII (N=9) | 101.3 ± 34.9 | 27.9 ± 6.9 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | *10.6 ± 3.1 | |

| Vagalall | TI (N=9) | 145.6 ± 34.9 | *41.7 ± 9.7 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 8.7 ± 2.1 |

| TII (N=9) | 112 ± 37.7 | 27.9 ± 6.9 | 4 ± 0.7 | *11.9 ± 3.3 | |

| AP | TI (N=9) | *121.7 ± 29.4 | *12.3 ± 2.7 | 10.1 ± 2.7 | 7.2 ± 1.4 |

| TII (N=9) | 78.4 ± 35.3 | 7.9 ± 2.1 | 10.0 ± 3.7 | 8.4 ± 3.5 | |

Correction for differences in body size not justified due to insignificant relationship between total cell number and standard length.

Indicates significant difference between morphs (p < 0.05).

TH-ir Cell Counts

Forebrain

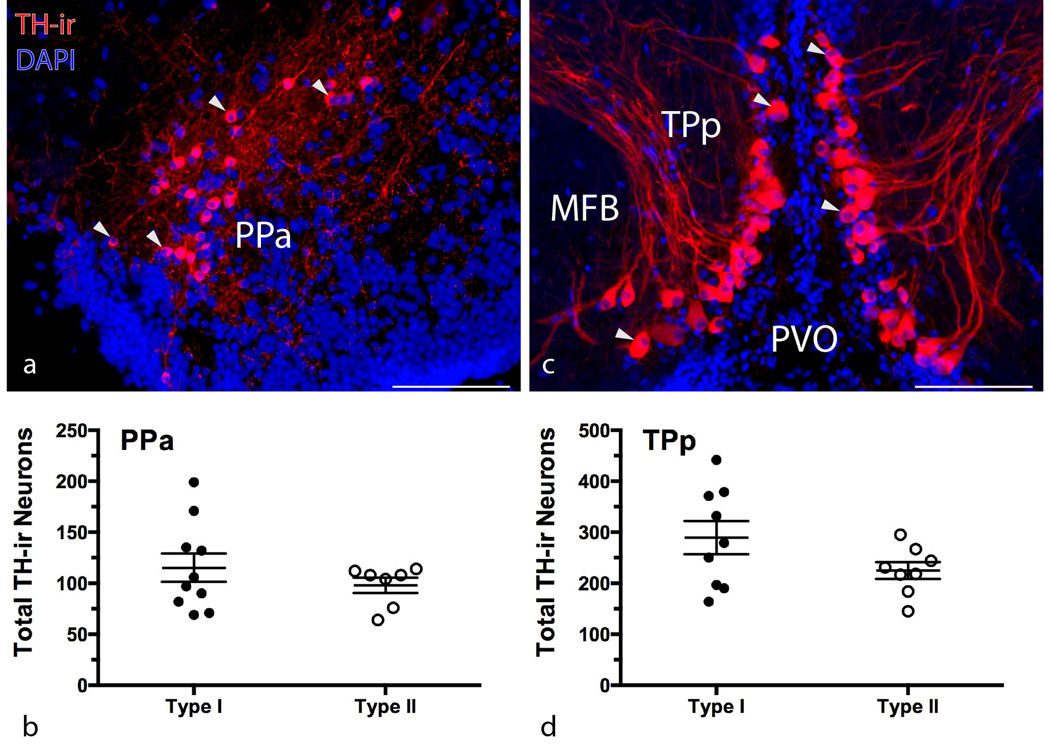

There were no significant differences in total TH-ir cell number between morphs in the PPa (Figure 1b) and TPp (Figure 1d) (unpaired t-test, p > 0.1 in both cases), and there was also no relationship between SL and the total number of PPa neurons (p > 0.1) or TPp neurons (p > 0.07)..

Figure 1.

Intrasexual morphometric comparison of forebrain T H-ir nuclei. Micrographs depict TH-ir neurons (arrowheads) in representative transverse sections through the anterior parvocellular preoptic nucleus (PPa) (a) and periventricular posterior tuberculum (TPp) (c) in a type I male. Right edge of (a) is at the midline, (c) is centered on the midline. MFB = medial forebrain bundle, PVO = paraventricular organ. Scatter dot plots in (b) and (d) represent mean ± SE number of total TH-ir neurons. Scale bar = 100 µm.

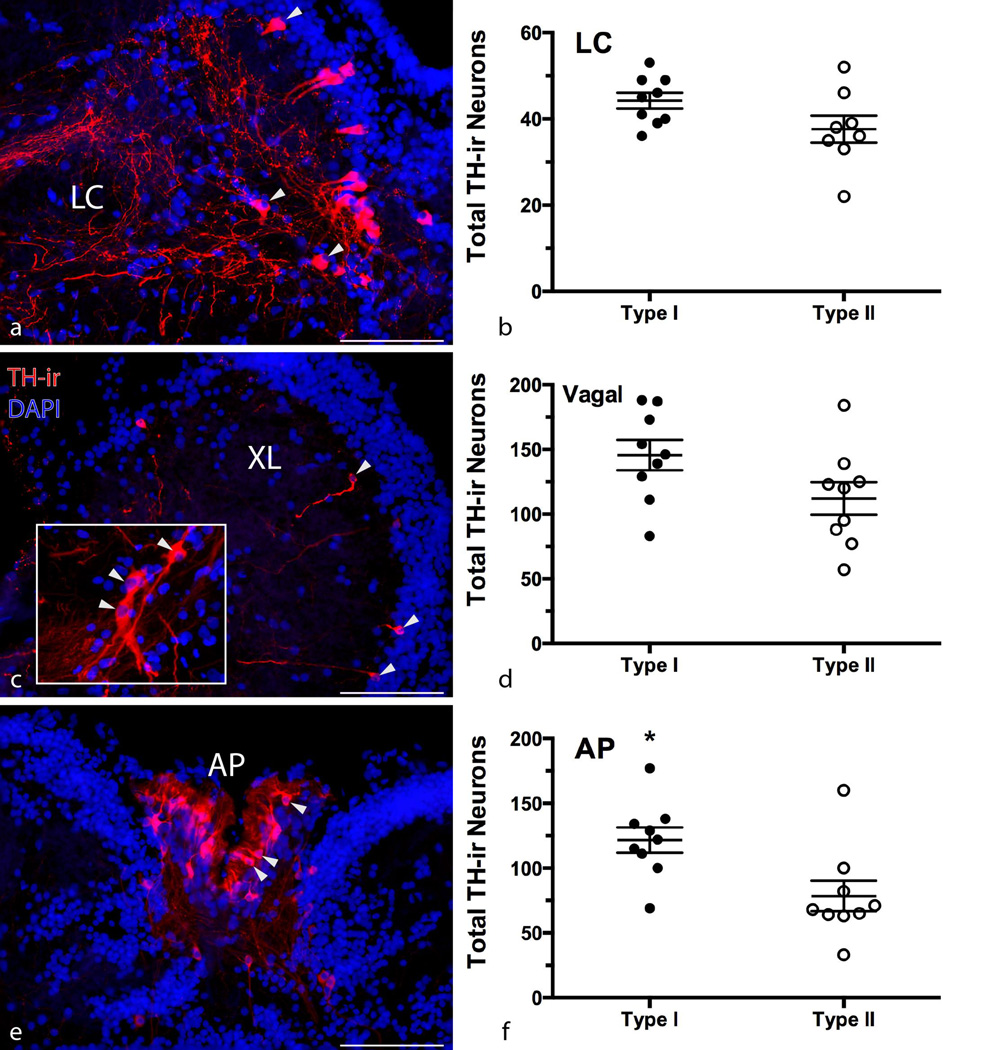

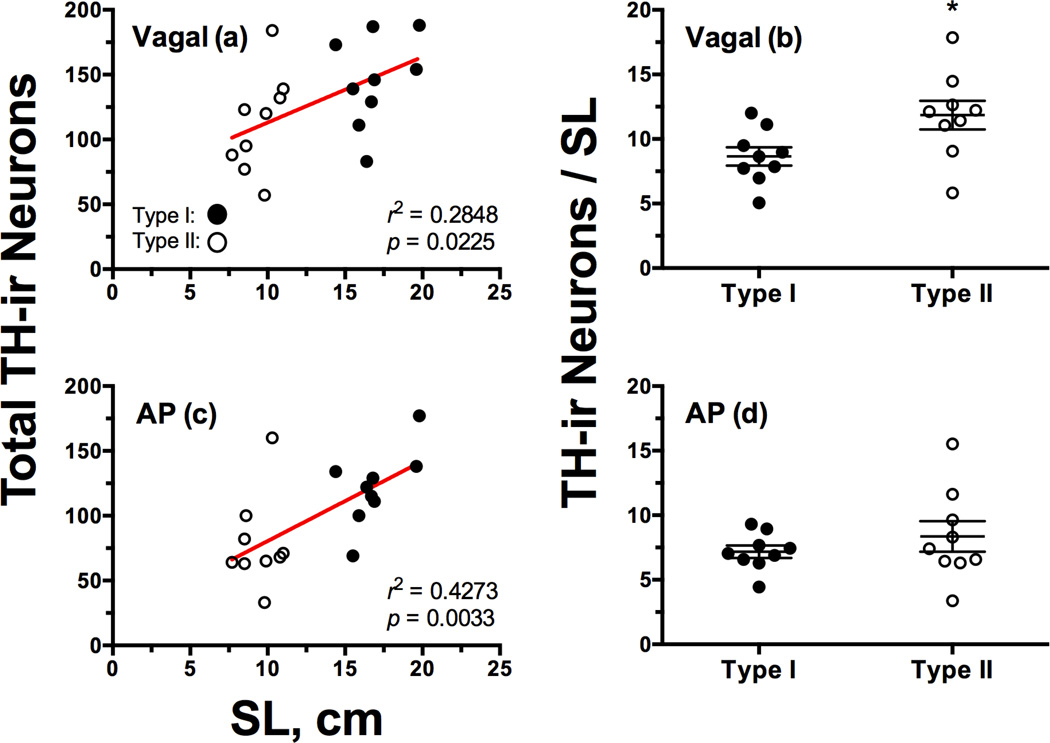

Hindbrain

Similar to forebrain nuclei, there was not a significant difference in total cell number between morphs in the LC (unpaired t-test, p > 0.08) (Figure 2b), and there was no relationship between SL and the total number of LC TH-ir neurons (p > 0.1). With regard to total TH-ir cell number in the vagal nuclei, there was no difference between morphs (unpaired t-test, p > 0.07) (Figure 2d), but type I males did have significantly more total neurons in the AP (t16 = 2.819, p = 0.0123; type I = 121.7 ± 9.815; type II = 78.44 ± 11.78) (Figure 2f). However, there were significant relationships between SL and total numbers of TH-ir neurons associated with vagal nuclei (r2 = 0.2867, p = 0.022) (Figure 3a) and AP (r2 = 0.4273, p = 0.0033) (Figure 3c). After correcting for differences in body size, type II males had 31.4% more vagal TH-ir neurons per cm of body length (t16 = 2.538, p = 0.0219; type I = 8.637 ± 0.7007; type II = 11.85 ± 1.1056) (Figure 3b). There was no difference between morphs after correcting for body size in the AP (Welch-corrected t-test, p > 0.3) (Figure 3d).

Figure 2.

Intrasexual morphometric comparison of hindbrain TH-ir nuclei. Micrographs depict TH-ir neurons (arrowheads) in representative transverse sections through the locus coeruleus (LC) (a), vagal lobe (XL) (c), and area postrema (AP) (e) in a type II male. Right edges of (a) and (c) are at the midline of the brain, (e) is centered on the midline. Inset in (c) depicts larger extraventricular vagal neurons lying caudal and ventrolateral to smaller paraventricular neurons in XL. Scatter dot plots in (b), (d), and (f) represent mean ± SE number of total TH-ir neurons. *p = 0.0123. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 3.

Intrasexual morphometric analysis of the relationship between total TH-ir cell number and body size in the hindbrain. Pearson correlations of total TH-ir cell number scaled to standard length in the vagal-associated nuclei (paraventricular and extraventricular cells combined) (a) and area postrema (AP) (c). Closed circles represent type I males, open circles are type II males. Scatter dot plots in (b) and (d) represent mean ± SE number of TH-ir neurons corrected for body size. *p = 0.0219. See Table 2 for statistical breakdown of TH-ir vagal subgroups.

Relative contribution of paraventricular and extraventricular TH-ir neurons to variation in normalized vagal-associated cell density

Our initial analysis of CA vagal neurons included all cells counted throughout this area of the brain. In zebrafish, TH-ir vagal cells are demarcated into small, monopolar, paraventricular dopaminergic and larger, bipolar extraventricular noradrenergic subgroups using an antibody raised against dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH-ir) [Kaslin and Panula, 2001]. Since the total number of vagal TH-ir neurons varied with body size in our study (Figure 3a), and type II males had more neurons per cm of body length (Figure 3b), we wanted to determine which neuroanatomical subgroup contributed to variation in normalized cell number between morphs. There was no difference in the total number of paraventricular TH-ir cells between morphs (p > 0.6), but there was a trend for type I males having more total extraventricular cells (t16 = 2.102, p = 0.0518; type I = 133.4 ± 9.916; type II = 101.3 ± 11.62). While the total number of paraventricular cells was not correlated to body size (p > 0.8), there was a significant relationship between the total number of extraventricular vagal cells and SL (r2 = 0.3241, p = 0.0137). After size correction, type II males had 28.5% more extraventricular vagal TH-ir neurons per cm of body length (t16 = 2.204, p = 0.0425; type I = 7.992 ± 0.63; type II = 10.65 ± 1.029). It is important to note that out of all TH-ir vagal cells measured, extraventricular cells comprised over 90% of those subsampled (Table 2). These results demonstrate that the putatively noradrenergic extraventricular vagal TH-ir cells contribute to variation in neuron number corrected for body size between morphs.

TH-ir Fiber Analysis

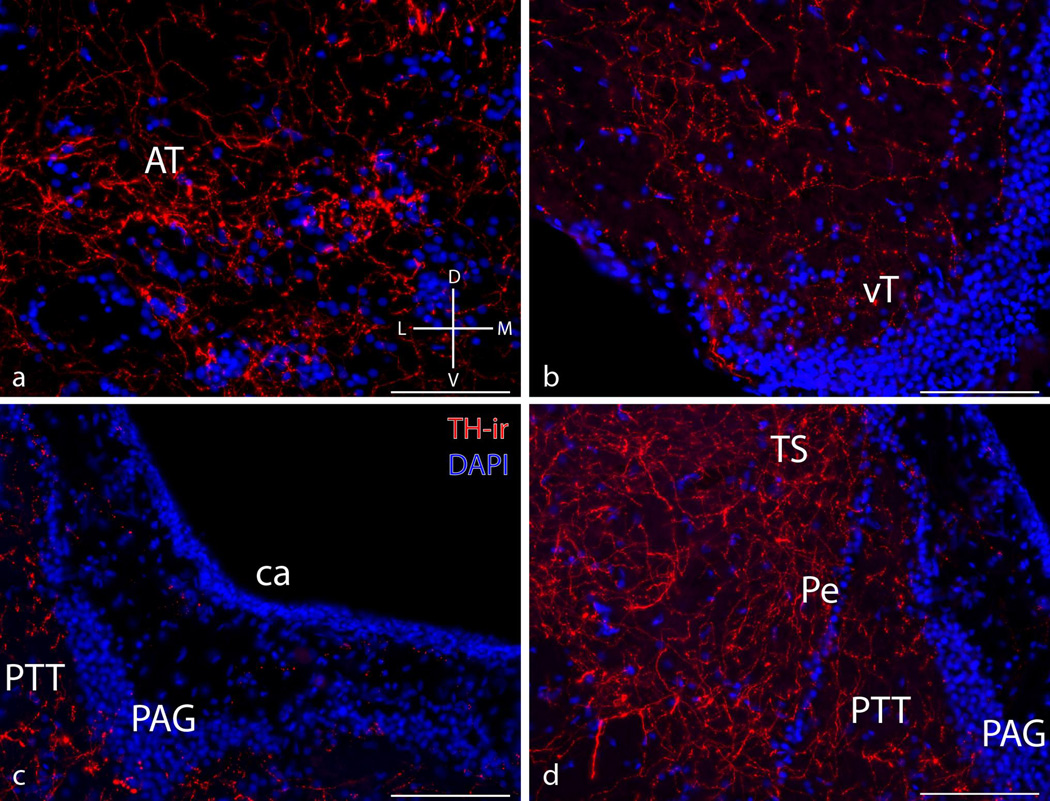

Hypothalamus, midbrain, and hindbrain

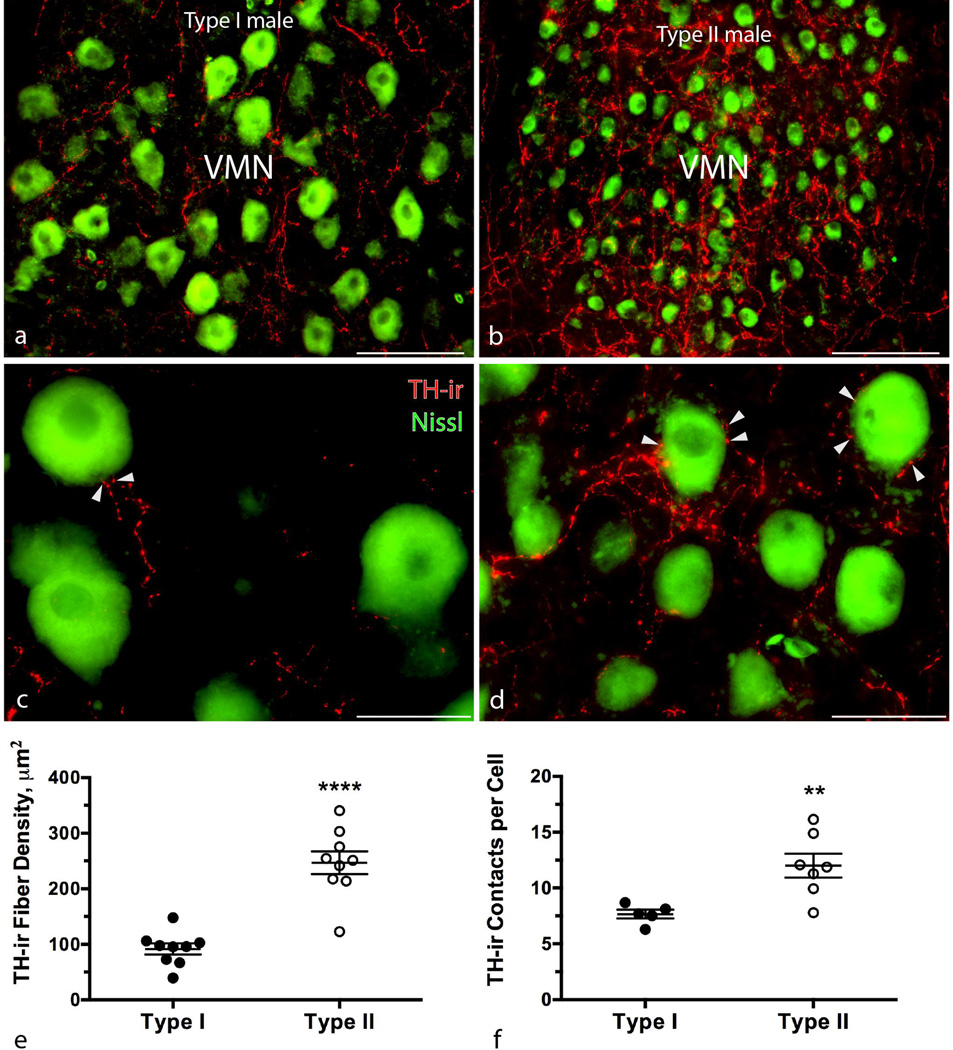

There were no significant differences in percent area covered by TH-ir fibers or intensity within the AT, vT, PAG, or PTT (unpaired t-test, p > 0.07 in all cases) (Figure 4). Within the VMN, type II males had a greater TH-ir fiber density per fractional area (5,692.7 µm2) (t16 = 6.801, p < 0.0001; type I = 91.63 ± 10.04 µm2; type II = 246.8 ± 20.48 µm2) (Figure 5e). While significant differences in integrated (total) intensity (measured in arbitrary units, AU) reflected differences in fiber density (t16 = 6.496, p < 0.0001; type I = 96,842 ± 10,761 AU; type II = 246,657 ± 20,397 AU), TH-ir fibers in the VMN of type I males had higher average intensity per fractional area (t16 = 3.349, p = 0.0041; type I = 112.1 ± 1.213 AU; type II = 107.1 ± 0.8978 AU). As expected, a greater portion of the sampling area was taken up by motor neuron somata in type I males [Bass and Marchaterre, 1989; Bass et al., 1996] (t16 = 3.75, p = 0.0017; type I = 1,053 ± 54.38 µm2; type II = 774.1 ± 50.74 µm2). The area of overlap between TH-ir fibers and motor neuron somata was greater in type II males (t16 = 6.79, p < 0.0001; type I = 9.036 ± 2.067 µm2; type II = 25.06 ± 1.14 µm2). Additionally, type II males had 44.1% more putative TH-ir contacts per motor neuron (Welch-corrected t7.56 = 3.793, p = 0.0059; type I = 7.666 ± 0.3985; type II = 12 ± 1.071) (Figure 5f).

Figure 4.

Micrographs showing representative transverse sections through the hypothalamic and midbrain components of the vocal-motor pathway in a type II male. Anterior tuberal hypothalamus (AT) (a), ventral tuberal hypothalamus (vT) (b), midbrain periaqueductal grey (PAG) (c), and paratoral tegmentum (PTT) (d). Compass in bottom right corner of (a) indicates anatomical orientation across all images: D = dorsal; V = ventral; M = medial; L = lateral. ca = cerebral aqueduct, Pe = periventricular cell layer of TS = torus semicircularis. Mean ± SE TH-ir fiber density for type I vs. type II males: AT (7.37 ± 1.28% vs. 9.1 ± 1.19%); vT (2.59 ± 0.12% vs. 3.1 ± 0.25%); PAG (1.9 ± 0.28% vs. 1.84 ± 0.31%); PTT (7.51 ± 0.82% vs. 7.96 ± 0.89%). Scale bar = 100 µm.

Figure 5.

Intrasexual morphometric comparison of TH-ir fiber density within the vocal motor nucleus (VMN). Micrographs depict representative transverse sections through the VMN at low and high magnifications in a type I (a, c) and type II (b, d) male, Arrowheads in c and d indicate punctate-type contacts on individual motor neurons. Scatter dot plots in (e) represent mean ± SE TH-ir fiber density per fractional area (5,692.7 µm2); (f) are mean ± SE number of putative TH-ir contacts per cell. ****p < 0.0001; **p = 0.0059. Scale bar in (a) and (b) = 100 µm, scale bar in (c) and (d) = 35 µm.

DISCUSSION

Our study found intrasexual dimorphisms in TH-ir neuron and fiber density in close proximity to and within a major component of the hindbrain vocal pattern generator, providing compelling evidence that differences in brain catecholamines (CAs) are an underlying character within the suite of traits that are divergent in male midshipman exhibiting alternative reproductive tactics [see Bass and Forlano, 2008]. Interestingly, quantitative analyses of TH-ir fiber innervation in vocal nuclei in the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain only revealed a significant difference between male morphs in the VMN that spans the hindbrain-spinal transition [Bass et al., 2008]. This difference was evident as both greater overall density of TH-ir fibers per fractional area of the nucleus and also a greater number of putative contacts per VMN soma in type II males. Our measure of contacts per motor neuron included putative CA release sites in close proximity to the edges of sampled motor neurons due to the fact that CAs are well established to be released volumetrically at non-classical synapses in a paracrine fashion [Descarries et al., 2008]. Although inter- and intrasexual dimorphisms of VMN neurons and their efferent muscle targets have been well characterized physiologically and morphologically [Bass and Marchaterre, 1989; Bass and Baker, 1990; Bass et al., 1996], this is the first report of morph differences in efferent fibers to the VMN. It is possible that without TH-ir labeling, morph differences in VMN inputs may not be obvious, especially if TH-ir neurons do not form classical synapses in this area. This could explain why an earlier TEM study did not detect differences in synaptology of the vocal motor nucleus between morphs [Bass and Marchaterre, 1989]. It is interesting to note that we found a small (~5%) but significant difference in average intensity of TH-ir fibers in the VMN that was greater in type I males, although the biological relevance of such a small difference is questionable. Average fiber intensity measurements may reflect differences in enzyme expression independent of density of TH-ir efferent inputs and may indicate a tradeoff of CA production per axon versus greater numbers of efferents per target area.

Origin of male morph differences in TH-ir fiber innervation of VMN

Although the VMN appears to receive input from neighboring TH-ir neurons in XL and AP [Forlano et al., 2014], descending projections from the TPp and LC could also contribute to TH-ir fibers terminating in the VMN, being consistent with known descending projection patterns of these nuclei into the hindbrain and spinal cord of teleosts, notably, the TPp and its diencephalospinal projections as proposed homologs to dopaminergic A11 neurons in mammals [McLean and Fetcho, 2004a, 2004b; Tay et al., 2011; Schweitzer et al., 2012; Forlano et al., 2014; Jay et al., 2015]. Since we utilized TH-ir as a marker for CA neurons, we were unable to distinguish between relative contributions of dopaminergic and noradrenergic fibers in the VMN. However, after differentiating between paraventricular and extraventricular vagal TH-ir neurons [Ma, 1997; Kaslin and Panula, 2001], we determined that the putatively noradrenergic extraventricular neurons contributed to variation in normalized TH-ir cell density between morphs. This suggests possible differential noradrenergic modulation of vocal-motor function between type I and type II males, as they appear to provide significant CA input into the VMN of midshipman [Forlano et al., 2014]. These vagal nuclei are also proposed homologues of the A2 group and its subset in rats, which indeed show a similar neuroanatomical distribution of TH-and DBH-containing neurons. [Hökfelt et al. 1984; Kaslin and Panula, 2001]. Future studies will need to further elucidate any morph differences in CA type, but perhaps more importantly identify the expression of various CA receptor subtypes which would give insight to variation of modulatory input and action on VMN neurons (see below). Although we did not find differences of TH-ir fiber innervation in higher order vocal centers, it is also possible that differential input of dopamine (DA) vs. noradrenaline (NA) may underlie the same total CA fiber density between morphs.

CA innervation and multiple types of DA and NA receptors have been localized not only on spinal motor neurons across vertebrate taxa [Svensson et al., 2003; McLean and Fetcho, 2004b; Tay et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2015], but more importantly on homologous VPG nuclei across vertebrates. For instance, a recent study in rats revealed that expiratory laryngeal motor neurons in the nucleus ambiguus receive close appositions from descending TH-ir varicosities that originate, in part, from the AP and nucleus tractus solitarius [Zhao et al., 2015]. These caudal TH- ir groups also likely provide local innervation of the nucleus ambiguus in mammals [Rinaman, 2011], the tracheosyringeal division of the hypoglossal motor nucleus in birds [Bottjer, 1993; Mello et al., 1998; Appeltants et al., 2001], and the vagal motor nucleus and inferior reticular formation (Ri) in amphibians [Gonzalez and Smeets, 1991], all comparable vocal areas to midshipman VPG nuclei [Bass et al., 2008; Bass, 2014]. As a result, CA modulation of vocal motor patterning may also be a conserved vertebrate character [Forlano et al., 2014].

Functional implications of morph differences in TH-ir innervation of the VMN

Although electrical stimulation at various levels along the vocal motor pathway can elicit short, isolated fictive agonistic “grunts” in type II males and females [Goodson and Bass, 2000a; Remage-Healey and Bass, 2007], these are rarely if ever heard in field recordings [Brantley and Bass, 1994]. Type II males are referred to as “sneaker” males which attempt to steal fertilizations from type I males by surreptitiously gaining access to a type I nest when a female is in the process of depositing her eggs [Brantley and Bass, 1994]. Therefore, minimizing vocalizations would be advantageous for successfully employing this reproductive tactic. Our findings, which demonstrate a strong inverse relationship between density of TH-ir innervation in the VMN and the predominant vocal phenotype, suggest catecholamines may function, in part, to directly inhibit vocal behavior during the breeding season.

There are multiple examples from diverse taxa that show inhibitory action of NA and or DA on vocal circuitry and behavior, although this can vary depending on the receptor that is targeted. Preliminary experimental work in midshipman found that both D1- and D2-like receptors contributed to DA-induced suppression of fictive vocalizations initiated at the level of the PAG [Heisler and Kittelberger, 2012]. Likewise, the drd2 transcripts which encode D2-like dopamine receptor subtypes are upregulated in the VMN relative to the surrounding hindbrain [Feng et al. 2015]. In zebra finches, NA suppresses activity in the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA), a forebrain premotor song control nucleus, via α2-adrenergic receptors (ARs) [Solis and Perkel, 2006]. Similarly NA inhibits the medullary respiratory rhythm generator in newborn rats [Errchidi et al., 1991]. In contrast, NA can have excitatory effects on the firing properties of hypoglossal motor neurons in juvenile rats via α1-adrenoceptors [Parkis et al., 1995]. The inhibitory effect of DA is evident in lamprey, where DA can presynaptically inhibit glutamatergic reticulospinal transmission through D2-receptors [Svensson et al., 2003]. Interestingly, TPp neurons projecting to spinal motor neurons in larval zebrafish show different firing patterns during locomotion and while stationary, and this appears to be dependent on synaptic input to these DA neurons [Jay et al., 2015]. In green tree frogs, activation of D2-like receptors has an inhibitory effect on male advertisement calling, while D1-like and non-specific DA agonists have no effect on vocal behavior [Creighton et al., 2013]. In adult rats, D1-and- D2-receptor antagonism resulted in fewer ultrasonic vocalizations, including delayed initiation of calls and subdued signal complexity [Ringel et al., 2013].

Possible mechanisms for intrasexual male differences in TH-ir

Males were all collected early in the breeding season, characterized as a period of intense vocal courtship by type I males and corresponding sneaking behavior by type IIs [Brantley and Bass, 1994; Sisneros et al., 2004, 2009], therefore, the present study provides a snapshot of brain CA density and distribution at this phase of the reproductive period. At this time of collection, type I males are known to have high levels of circulating 11-ketotestosterone (11-KT) compared to later in the summer during parental phase [Knapp et al., 1999; Sisneros et al., 2004], while type II males have undetectable 11-KT, they have higher plasma levels of testosterone and cortisol compared to type I’s [Brantley et al., 1993; Arterbery et al., 2010a]. Male morphs are not only divergent in circulating steroid levels but also in brain aromatase, 11β-hydroxylase (11β-H), 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD), as well as glucocorticoid and estrogen receptor expression [Schlinger et al., 1999; Arterbery et al., 2010a, 2010b; Bass and Forlano, 2008; Fergus and Bass 2013]. Because steroid hormones are known to regulate CA expression and/or correlate with TH-ir neuron number and fiber density [Wilczynski et al., 2003; Weltzien et al., 2006; LeBlanc et al., 2007; Matragrano et al., 2011], differential circulating or brain-derived steroid hormones may underlie morph differences in the number of TH-ir vagal neurons and innervation patterns of TH-ir fibers terminating into the VMN. Since steroid hormone levels vary seasonally and with vocal behavior in type I males [Sisneros et al., 2004; Genova et al., 2012], there may yet prove to be plasticity in TH-ir innervation of VMN within male morphs between seasons (and likely between courtship and parental phase within the summer reproductive season in type I males), similar to our findings in the auditory system of females [Forlano et al., 2015]. Compellingly, the density of α2-ARs in the song control nuclei of male European starlings varies seasonally, showing an inverse relationship between circulating t estosterone, song nuclei volume, and singing behavior [Riters et al., 2002; Heimovics et al., 2011].

Conclusions

Differential numbers of TH-ir vagal neurons proximal to VMN and CA fiber innervation of the VMN between divergent male morphs of the same species supports a role for catecholamines as important modulators of vocal behavior related to reproductive phenotype. Further studies will be necessary to reveal the distribution of specific CA subpopulations and their receptor subtypes in the vocal-motor pathway of midshipman, and how they may relate to differences in vocal behavior.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab, Sisneros Lab, and Midge Marchaterre for logistical support, Chris Petersen for assisting with perfusions and providing analytical insight, as well as Chris Braun and Thomas Preuss for imparting constructive feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript. We also wish to thank Frank Burbrink, Frank Grasso, Jonathan Perelmuter, and Sunny Scobell for valuable discussions on matters of biometry, and Spencer Kim for histological assistance and contributing authoritative macroinstruction in MetaMorph. Lastly, we thank two anonymous reviews that improved the quality of this paper.

Grant sponsors: National Institutes of Health, grant number: SC2DA034996 (to P.M.F.); CUNY Graduate Center Doctoral Student Research Grant, number: 9 (to Z.N.G.).

WORKS CITED

- Appeltants D, Ball GF, Balthazart J. The distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase in the canary brain: demonstration of a specific and sexually dimorphic catecholaminergic innervation of the telencephalic song control nulcei. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;304:237–259. doi: 10.1007/s004410100360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appeltants D, Ball GF, Balthazart J. The origin of catecholaminergic inputs to the song control nucleus RA in canaries. Neuroreport. 2002a;13:649–653. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200204160-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appeltants D, Ball GF, Balthazart J. Noradrenergic control of auditory information processing in female canaries. Behav Brain Res. 2002b;133:221–235. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arterbery AS, Deitcher DL, Bass AH. Corticosteroid receptor expression in a teleost fish that displays alternative male reproductive tactics. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2010a;165:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arterbery AS, Deitcher DL, Bass AH. Divergent expression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and 11β-hydroxylase genes between male morphs in the central nervous system, sonic muscle and testis of a vocal fish. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2010b;167:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth C, Villringer A, Sacher J. Sex hormones affect neurotransmitters and shape the adult female brain during hormonal transition periods. Front. Neurosci. 2015;9:1–20. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH. Dimorphic male brains and alternate reproductive tactics in a vocalizing fish. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:139–145. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90356-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH. Shaping brain sexuality. Am. Sci. 1996;84:352–363. [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH. Central pattern generator for vocalization: is there a vertebrate morphotype? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014;28:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH, Baker R. Sexual dimorphisms in a vocal control system of a teleost fish: morphology of physiologically identified neurons. J Neurobiol. 1990;21:1155–1168. doi: 10.1002/neu.480210802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH, Forlano PM. Neuroendocrine mechanisms of alternative reproductive tactics: the chemical language of reproductive and social plasticity. In: Oliveira RF, Taborsky M, Brockmann HJ, editors. Alternative Reproductive Tactics: An Integrative Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 109–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH, Marchaterre MA. Sound-generating (sonic) motor system in a teleost fish (Porichthys notatus): sexual polymorphisms and general synaptology of sonic motor nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1989;286:154–169. doi: 10.1002/cne.902860203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH, McKibben JR. Neural mechanisms and behaviors for acoustic communication in teleost fish. Prog. Neurobiol. 2003;69:1–26. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH, Marchaterre MA, Baker R. Vocal-acoustic pathways in a teleost fish. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4025–4039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04025.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH, Horvath BJ, Brothers EB. Nonsequential developmental trajectories lead to dimorphic vocal circuitry for males with alternative reproductive tactics. J Neurobiol. 1996;30:493–504. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199608)30:4<493::AID-NEU5>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH, Gilland EH, Baker R. Evolutionary origins for social vocalization in a vertebrate hindbrain-spinal compartment. Science. 2008;321:417–421. doi: 10.1126/science.1157632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottjer SW. The distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the brains of male and female zebra finches. J Neurobiol. 1993;24:51–69. doi: 10.1002/neu.480240105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantley RK, Bass AH. Alternative male spawning tactics and acoustic signaling in the plainfin midshipman fish, Porichthys notatus. Ethology. 1994;96:213–232. [Google Scholar]

- Brantley RK, Wingfield JC, Bass AH. Hormonal bases for male teleost dimorphisms: Sex steroid levels in Porichthys notatus, a fish with alternative reproductive tactics. Horm Behav. 1993;27:332–347. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1993.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelino CB, Ball GF. A role for norepinephrine in the regulation of context dependent ZENK expression in male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1962–1972. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagnaud BP, Baker R, Bass AH. Vocalization frequency and duration are coded in separate hindbrain nuclei. Nat. Comm. 2011;2:346. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton A, Satterfield D, Chu J. Effects of dopamine agonists on calling behavior in the green tree frog, Hyla cinerea Physiol. Behav. 2013;116–117:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran-Everett D. Explorations in statistics: the analysis of ratios and normalized data. Adv Physiol Educ. 2013;37:213–219. doi: 10.1152/advan.00053.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L, Berube-Carriere N, Riad M, Bo GD, Mendez JA, Trudeau LE. Glutamate in dopamine neurons: synaptic versus diffuse transmission. Brain Res Rev. 2008;58:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries MS, Cordes MA, Stevenson SA, Riters LV. Differential relationships between D1 and D2 receptor expression in the medial preoptic nucleus and sexually-motivated song in male European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) Neuroscience. 2015;301:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslin J, Panula P. Comparative anatomy of the histaminergic and other aminergic systems in zebrafish (Danio rerio) J Comp Neurol. 2001;440:342–377. doi: 10.1002/cne.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson J, Stephenson-Jones M, Pérez-Fernández J, Robertson B, Silderberg G, Grillner S. Dopamine differentially modulates the excitability of striatal neurons of the direct and indirect pathways in lamprey. J Neurosci. 2013;33:8045–8054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5881-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errchidi S, Moteau R, Hilaire G. Noradrenergic modulation of the medullary respiratory rhythm generator in the newborn rat: an in vitro study. J Physiol. 1991;443:477–498. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng NY, Fergus DJ, Bass AH. Neural transcriptome reveals molecular mechanisms for temporal control of vocalization across multiple timescales. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:408. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1577-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus DJ, Bass AH. Localization and divergent profiles of estrogen receptors and aromatase in the vocal and auditory networks of a fish with alternative mating tactics. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:2850–2869. doi: 10.1002/cne.23320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran CM, Bass AH. Preoptic AVT immunoreactive neurons of a teleost fish with alternative reproductive tactics. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1998;111:271–282. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano PM, Bass AH. Steroid regulation of brain aromatase expression in glia: female preoptic and vocal motor nuclei. J Neurobiol. 2005;65:50–58. doi: 10.1002/neu.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano PM, Deitcher DL, Myers DA, Bass AH. Anatomical distribution and cellular basis for high levels of aromatase activity in the brain of teleost fish: aromatase enzyme and mRNA expression identify glia as source. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8943–8955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-08943.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano PM, Deitcher DL, Bass AH. Distribution of estrogen receptor alpha mRNA in the brain and inner ear of a vocal fish with comparisons to sites of aromatase expression. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:91–113. doi: 10.1002/cne.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano PM, Marchaterre M, Deitcher DL, Bass AH. Distribution of androgen receptor mRNA expression in vocal, auditory, and neuroendocrine circuits in a teleost fish. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:493–512. doi: 10.1002/cne.22233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano PM, Kim SD, Krzyminska Z, Sisneros JA. Catecholaminergic connectivity to the inner ear, central auditory and vocal motor circuitry in the plainfin midshipman fish, Porichthys notatus. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:2887–2927. doi: 10.1002/cne.23596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano PM, Ghahramani ZN, Monestime CM, Kurochkin P, Chernenko A, Milkis D. Catecholaminergic innervation of central and peripheral auditory circuitry varies with reproductive state in female midshipman fish, Porichthys notatus. PLOS One. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genova RM, Marchaterre MA, Knapp R, Fergus D, Bass AH. Glucocorticoid and androgen signaling pathways diverge between advertisement calling and non-calling fish. Horm Behav. 2012;62:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebrecht GKE, Kowtoniuk RA, Kelly BG, Kittelberger JM. Sexually dimorphic expression of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the brain of a vocal teleost fish (Porichthys notatus) J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2014;56:13–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Smeets WJ. Comparative analysis of dopamine and tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivities in the brain of two amphibians, the anuran Rana ridibunda and the urodele Pleurodeles waltlii. J Comp Neurol. 1991;303:457–477. doi: 10.1002/cne.903030311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL, Bass AH. Forebrain peptides modulate sexually polymorphic vocal circuitry. Nature. 2000;403:769–772. doi: 10.1038/35001581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL, Bass AH. Vocal-acoustic circuitry and descending vocal pathways in a teleost fish: convergence with terrestrial vertebrates reveals conserved traits. J Comp Neurol. 2002;448:298–322. doi: 10.1002/cne.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober MS, Fox SH, Laughlin C, Bass AH. GnRH cell size and number in a teleost fish with two male reproductive morphs: sexual maturation, final sexual status and body size allometry. Brain Behav Evol. 1994;43:61–78. doi: 10.1159/000113625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara E, Kubikova L, Hessler NA, Jarvis ED. Role of the midbrain dopaminergic system in modulation of vocal brain activation by social context. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3406–3416. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimovics SA, Cornil CA, Ellis JMS, Ball GF, Riters LV. Seasonal and individual variation in singing behavior correlates with α2-noradrenergic receptors in brain regions implicated in song, sexual, and social behavior. Neuroscience. 2011;182:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler EK, Kittelberger JM. Both D1- and D2-like receptors contribute to dopamine induced inhibition of vocal production in the midbrain periaqueductal gray of a teleost fish; Front. Behav. Neurosci. Conference Abstract: Tenth International Congress of Neuroethology; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hökfelt T, Mårtensson R, Björklund A, Kleinau S, Goldsten M. Distributional maps of tyrosine-hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons in the rat brain. In: Björklund A, Hökfelt T, editors. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy Part I, Vol. 2.: Classical transmitters in the CNS. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1984. pp. 277–379. [Google Scholar]

- Jay M, DeFaveri F, McDearmid R. Firing dynamics and modulatory actions of supraspinal dopaminergic neurons during zebrafish locomotor behavior. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabelik D, Schrock SE, Ayres LC, Goodson JL. Estrogenic regulation of dopaminergic neurons in the opportunistically breeding zebra finch. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2011;173:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AM, Goodson JL. Functional interactions of dopamine cell groups reflect personality, sex, and social context in highly social finches. Behav Brain Res. 2015;280:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittelberger JM, Bass AH. Vocal-motor and auditory connectivity of the midbrain periaqueductal gray in a teleost fish. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:791–812. doi: 10.1002/cne.23202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp R, Wingfield JC, Bass AH. Steroid hormones and paternal care in the plainfin midshipman fish (Porichthys notatus) Horm Behav. 1999;35:81–89. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc MM, Good CT, MacDougall-Shackleton EA, Maney DL. Estradiol modulates brainstem catecholaminergic cell groups and projections to the auditory forebrain in a female songbird. Brain Res. 2007;1171:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma PM. Catecholaminergic Systems in the Zebrafish. III. O rganization and Projection Pattern of Medullary Dopaminergic and Noradrenergic Neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1997;381:411–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matragrano LL, Sanford SE, Salvante KG, Sockman KW, Maney DL. Estradiol-dependent catecholaminergic innervation of auditory areas in a seasonally breeding songbird. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:416–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07751.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matragrano LL, LeBlanc MM, Chitrapu A, Blanton ZE, Maney DL. Testosterone alters genomic responses to song and monoaminergic innervation of auditory areas in a seasonally breeding songbird. Dev Neurobiol. 2013;73:455–468. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIver EL, Marchaterre MA, Rice AN, Bass AH. Novel underwater soundscape: acoustic repertoire of plainfin midshipman fish. J Exp Biol. 2014;217:2377–2389. doi: 10.1242/jeb.102772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean DL, Fetcho JR. Ontogeny and innervation patterns of dopaminergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic neurons in larval zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 2004a;480:38–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean DL, Fetcho JR. Relationship of tyrosine hydroxylase and serotonin immunoreactivity to sensorimotor circuitry in larval zebra fish. J Comp Neurol. 2004b;480:57–71. doi: 10.1002/cne.20281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CV, Pinaud R, Ribeiro S. Noradrenergic system of the zebra finch brain: immunocytochemical study of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. J Comp Neurol. 1998;400:207–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda JA, Oliveira RF, Carniero LA, Santos RS, Grober ME. Neurochemical correlates of male polymorphism and alternative reproductive tactics in the Azorean rock-pool blenny, Parablennius parvicornis. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2003;132:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s0016-6480(03)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell LA, Hofmann HA. The vertebrate mesolimbic reward system and social behavior network: a comparative synthesis. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:3599–3639. doi: 10.1002/cne.22735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkis MA, Bayliss DA, Berger AJ. Actions of norepinepherine on rat hypoglossal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1911–1919. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen CL, Timothy M, Kim SD, Bhandiwad AA, Mohr RA, Sisneros JA, Forlano PM. Exposure to advertisement calls of reproductive competitors activates vocal-acoustic and catecholaminergic neurons in the plainfin midshipman fish, Porichthys notatus. PLOS One. 2013;8:e70474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remage-Healey L, Bass AH. Plasticity in brain sexuality is revealed by the rapid actions of steroid hormones. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1114–1122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4282-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaman L. Hindbrain noradrenergic A2 neurons: diverse roles in autonomic, endocrine, cognitive, and behavioral functions. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:222–235. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00556.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringel LE, Basken JN, Grant LM, Ciucci MR. Dopamine D1 and D2 receptor antagonism effects on rat ultrasonic vocalizations. Behav Brain Res. 2013;252:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riters LV. The role of motivation and reward neural systems in vocal communication in songbirds. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33:194–209. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riters LV, Eens M, Pinxten R, Ball GF. Seasonal changes in the densities of α2-noradrenergic receptors are inversely related to changes in testosterone and the volumes of song control nuclei in male European starlings. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:63–74. doi: 10.1002/cne.10131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger BA, Greco C, Bass AH. Aromatase activity in the hindbrain vocal control region of a teleost fish: divergence among males with alternative reproductive tactics. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1999;266:131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer J, Lohr H, Filippi A, Driever W. Dopaminergic and noradrenergic circuit development in zebrafish. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:256–268. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisneros JA, Forlano PM, Knapp R, Bass AH. Seasonal variation of steroid hormone levels in an intertidal-nesting fish, the vocal plainfin midshipman. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2004;136:101–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisneros JA, Alderks PW, Leon K, Sniffen B. Morphometric changes associated with the reproductive cycle and behaviour of the intertidal-nesting, male plainfin midshipman Porichthys notatus. J Fish Biol. 2009;74:18–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis MM, Perkel DJ. Noradrenergic modulation of activity in a vocal control nucleus in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:2265–2276. doi: 10.1152/jn.00836.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson E, Wikström MA, Hill RH, Grillner S. Endogenous and exogenous dopamine presynaptically inhibits glutamatergic reticulospinal transmission via an action of D2-receptors on N-type Ca2+ channels. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:447–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay TL, Ronneberger O, Ryu S, Nitschke R, Driever W. Comprehensive catecholaminergic projectome analysis reveals single-neuron integration of zebrafish ascending and descending dopaminergic systems. Nat. Comm. 2011;2:171. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltzien F, Pasqualini C, Sébert M, Vidal B, Belle NL, Kah O, Vernier P, Dufour S. Androgen-dependent stimulation of brain dopaminergic systems in the female european eel (Anguilla anguilla) Endocrinology. 2006;147:2964–2973. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski W, Yang E, Simmons D. Sex differences and hormone influences on tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive cells in the leopard frog. J Neurobiol. 2003;56:54–65. doi: 10.1002/neu.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Vernier P. The evolution of dopamine systems in chordates. Front Neuroanat. 2011;5:21. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2011.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao WS, Rui-Chen Q, Pilowsky G. Catecholamine inputs to expiratory laryngeal motoneurons in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523:381–390. doi: 10.1002/cne.23677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]