Abstract

Food insecurity is linked to obesity among some, but not all, racial and ethnic populations. We examined the prevalence of food insecurity and the association between food insecurity and obesity among American Indians (AIs) and Alaska Natives (ANs) and a comparison group of whites. Using the 2009 California Health Interview Survey, we analyzed responses from 592 AIs/ANs and 7371 white adults with household incomes at or below 200% of the federal poverty level. Food insecurity was measured using a standard 6-item scale. Sociodemographics, exercise, and obesity were all obtained using self-reported survey data. Logistic regression was used to estimate associations. The prevalence of food insecurity was similar among AIs/ANs and whites (38.7% vs 39.3%). Food insecurity was not associated with obesity in either group in analyses adjusted for sociodemographics and exercise. The ability to afford high-quality foods is extremely limited for low-income Californians regardless of race. Health policy discussions must include increased attention on healthy food access among the poor, including AIs/ANs, for whom little data exist.

Keywords: obesity, Native Americans, American Indians, food insecurity

INTRODUCTION

Food insecurity is defined as limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods.1 Nearly 15% of the US population is food insecure,2 and limited evidence suggests that this prevalence is much higher among American Indians (AIs) and Alaska Natives (ANs).3–7 A recent study reported that almost 40% of the families living on an Indian reservation in South Dakota were food insecure.4 Likewise, in a reservation-based sample of 187 AI households in Montana, 43% of those surveyed were food insecure.5 Our own previous work with reservation communities in Northern California and Washington uncovered numerous structural and environmental barriers to healthy eating, including geographic isolation, the high cost of fresh vegetables and fruits, and limited access to grocery stores and supermarkets.3,8

Food insecurity is associated with an increased risk for obesity,9–13 diabetes,14,15 and other chronic diseases.16–18 Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that food insecure women are, on average, 11 pounds heavier than food secure women.15 Additionally, compared to their food secure counterparts, food insecure women and men were significantly more likely to have diabetes (adjusted relative risk = 2.42; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.44–4.08) and hypertension (adjusted relative risk = 1.20; 95% CI: 1.04–1.38] even after adjusting for body mass index (BMI).15,19

Notably, the food insecurity–obesity paradox may vary by race and ethnicity. A study among an ethnically diverse group of Californians found that food insecurity was associated with obesity predominantly among Hispanic men and women.20 Similarly, one study reported that food insecurity was associated with obesity among a combined group of Hispanic, Asian, and African American women but not among non-Hispanic white women.9 The use of multiple instruments to define and measure food insecurity may contribute to the variation in findings.20,21 For instance, the US Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM),22 implemented widely as the national food security monitoring tool, has shown overall face validity and goodness-of-fit among Asians and Pacific Islanders23 but a high rate of misfit within the Samoan population.23 Thoug a paucity of data exist regarding the appropriateness and accuracy of the HFSSM among AIs/ANs, one study conducted on the subject found that the magnitude and significance of food insecurity differed significantly by choice of food insecurity measure and by choice of subset of food insecurity questions.24 These differences were even more significant for AI/AN households without children.24

The relationship between food insecurity and obesity continues to be poorly understood. The lower intake of nutrients25–27 and significant declines in vegetable and fruit consumption among food insecure individuals is one potential explanation.28,29 Other reasons may include behavioral adaptations to episodic food scarcity (such as the “thrifty gene” hypothesis),30,31 dietary substitutions,32,33 and a lack of geographic access to healthy foods.13,14 Yet no single framework explains the phenomenon. Research is further complicated by the strong link between food insecurity and poverty.34,35 Indeed, poverty has been conceptualized as the broad environmental, social, and political context for food insecurity, and a cycle of mutual influence may promote excess weight gain and poor health outcomes.34

Because AIs/ANs have an annual average household income that is substantially lower than non-Hispanic whites,36 and their access to healthy foods is severely restricted,3,8 they are at high risk for food insecurity. We therefore used data from a large, multi-ethnic community-based survey conducted in California to (1) estimate the prevalence of food insecurity in low-income AIs/ANs and whites and (2) examine the association between food insecurity and obesity in low-income AIs/ANs and whites.

METHODS

Setting and Sample

The California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) is a 2-stage geographically stratified random-digit-dial survey of households throughout California. Residential telephone numbers are selected from predefined geographic areas, and respondents are randomly selected from sampled households. The survey is administered every 2 years and focuses on general public health topics such as health behaviors and risk factors, health insurance coverage, and access to health care services. California has more federally recognized tribes (107) than any state except Alaska, and Los Angeles County is home to the largest urban AI/AN population in the country, thus making the CHIS one of the few randomized surveys with an adequate sample of AIs/ANs. Detailed information about the CHIS methods is available elsewhere.37

Measures

Food Insecurity

The 2009 CHIS measured food insecurity using a validated 6-question scale, derived from the 18-item US Department of Agriculture Household Food Security questionnaire.38 Survey questions assessed food-conserving behaviors and financial means to obtain adequate food in the past 12 months. This survey was only administered to respondents at or below 200% of the federal poverty level because food insecurity is most relevant for lower income groups. Consistent with the US Department of Agriculture guidelines, we created a 3-level variable: a score of 0 to 1 indicated high or marginal food security, 2 to 4 indicated low food security, and 5 to 6 indicated very low food security.22 We refer to high or marginal food security as food secure and low or very low food security as food insecure.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

We examined respondents’ age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, geographic location, income, and participation in a public assistance program as covariates. Age was grouped into the following categories: 18–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–64, and 65 years and older. Congruent with the US Census, AI/AN race was determined by self-identification, alone or in combination with other races.36 Our white category consisted of all persons who self-identified exclusively as white. In the 2009 CHIS, Hispanic ethnicity was measured separately from race. Thus, we treated Hispanic ethnicity as a separate variable. Dichotomous variables included education (at least a high school degree or not), marital status (living together/married or not), and rural or urban using Indian Health Service classifications.37 Participation in public assistance programs was defined by receiving assistance from Temporary Aid for Needy Families/Cal Works, Food Stamps, Women Infants and Children, or Supplemental Security Income. Income was categorized as very poor (0–99% federal poverty level) and poor (100–199% federal poverty level).

Obesity and Exercise

Body mass index was calculated using self-reported height and weight. Obesity was defined as a BMI of 30.0 or greater. We created a physical activity variable by multiplying the number of days in the past week that participants moderate physical activity and the average amount of time spent per day doing these activities.

Statistical Analysis

CHIS data were weighted to be representative of the general California population. All analyses incorporated these weights to account for the complex survey design and provide valid standard errors. Stata version 11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used to conduct all analyses. Statistical significance was based on a type I error rate of 0.05. Categorical variables were summarized by percentages with SEs and continuous variables were represented by means with SEs. Prevalence was estimated with 95% CIs and associations were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs.

Our initial analysis estimated the sex-specific prevalence of food insecurity among impoverished AIs/ANs and whites. We tested for racial group differences using chi-square analysis. Using logistic regression, we then tested whether the odds of food insecurity differed significantly by race, after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

We calculated the race- and sex-specific prevalence of obesity according to food insecurity status. To measure the race- and sex-specific associations between food insecurity and odds of obesity we used logistic regression with obesity as the dependent variable and adjusted for age, Hispanic ethnicity, education, marital status, geographic location, income, participation in a public assistance program, and exercise. Because previous studies have modeled associations between graded levels of food insecurity and obesity,9–13 we also evaluated associations of the 3-level food security variable (high or marginal, low, and very low food security) with obesity. In addition, we tested for interactions between food insecurity and Hispanic ethnicity to determine whether associations of food insecurity with obesity varied by ethnicity.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

In the 2009 CHIS, food insecurity was measured for 592 low-income AIs/ANs and 7371 low income whites. Participant characteristics were similar across groups (Table 1). Males and Hispanics comprised a higher percentage of the AI/AN group than the white group. AI/AN participants were poorer than whites and had greater use of public assistance programs. Additionally, over 60% of the AI/AN population resided in an urban area.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of American Indian/Alaska Native and White Participantsa

| Participant characteristic | American Indian/Alaska Native % (SE) | White % (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–30 | 33 (3.9) | 31 (1.4) |

| 31–40 | 19 (2.6) | 16 (1.2) |

| 41–50 | 20 (4.4) | 18 (1.3) |

| 51–64 | 14 (2.6) | 18 (1.0) |

| 65 and older | 14 (1.8) | 18 (0.7) |

| Male | 53 (3.4) | 43 (1.3) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 52 (4.0) | 39 (1.6) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Less than high school graduate | 35 (4.1) | 27 (1.4) |

| High school graduate or more | 65 (4.1) | 73 (1.4) |

| Married or living together | 43 (4.2) | 50 (1.7) |

| Urban residence | 63 (3.8) | 61 (1.3) |

| Income | ||

| 100%–199% of federal poverty level | 46 (4.4) | 57 (1.4) |

| 0%–99% of federal poverty level | 54 (4.4) | 43 (1.4) |

| Public assistance participationb | 30 (3.4) | 24 (1.2) |

|

| ||

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |

|

| ||

| Weekly minutes of moderate exercise | 161 (24.1) | 114 (6.8) |

All estimates are weighted.

Includes participation in Temporary Aid for Needy Families/Cal Works, Food Stamps, Women Infants and Children, or Supplemental Security Income.

Prevalence of Food Insecurity

The prevalence of food insecurity was high among both low income AIs/ANs and whites (Table 2) and did not differ significantly by racial group in unadjusted analyses (P = .89). Further, the odds of food insecurity did not differ significantly between AIs/ANs and whites in analyses adjusted for age, Hispanic ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, location, income, and public assistance (OR = 0.8, 95% CI: 0.6, 1.2 comparing AIs/ANs to whites).

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of Food Insecurity by Race and Sexa

| Sex | Race

|

|

|---|---|---|

| American Indian/Alaska Native | White | |

| Men | 37.5 (25.6, 51.1) | 37.7 (33.0, 42.7) |

| Women | 40.2 (31.4, 49.7) | 40.6 (36.4, 44.9) |

| All | 38.7 (31.1, 47.0) | 39.3 (36.4, 42.3) |

Prevalence given as percentage with 95% confidence intervals.

Food Insecurity and Obesity

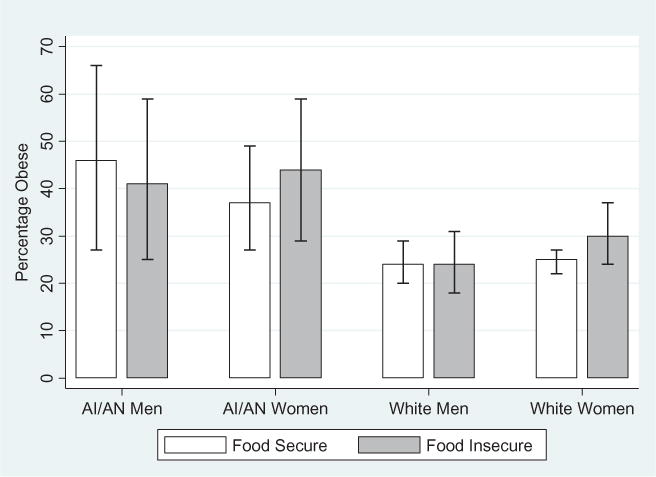

The prevalence of obesity was similar among the food secure and the food insecure in each subgroup defined by race and sex, as shown in Figure 1. Consistent with this pattern, we found no significant association between food insecurity and obesity in the subgroups defined by race and sex, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and exercise (Table 3). Likewise, using graded levels of food security, no significant associations were detected for the subgroups defined by race and sex (Supplemental Table 1). We also did not observe an interaction between Hispanic ethnicity and binary food insecurity. For the 3-level food insecurity variable, we had an insufficient number of observations to examine interactions among AIs/ANs. However, among white women the association between graded food security and obesity varied by Hispanic ethnicity. In contrast to our findings among non-Hispanic white women, Hispanic white women with very low food security had a greater likelihood of obesity than their food secure counterparts (OR = 2.9, 95% CI: 1.5, 5.6; Supplemental Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of obesity by race, sex, and food security. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (color figure available online).

TABLE 3.

Association of Food Insecurity With Obesity by Race and Sexa

| American Indian/Alaska Native men | American Indian/Alaska Native women | White men | White women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Food insecure vs food secure | 0.7 (0.2, 2.7) | 0.9 (0.4, 2.1) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.7) |

OR indicates odds ratio for obesity, comparing the food insecure to the food secure group; CI, confidence interval. ORs are adjusted for age, Hispanic ethnicity, education, marital status, residential location, income, public assistance, and physical activity.

DISCUSSION

We found no difference in the prevalence of food insecurity between AIs/ANs and whites in this sample of low-income adults. Further, food insecurity was not significantly associated with obesity in either the AI/AN or white group. Our study is consistent with the only other published study that examined the relationship between food insecurity and obesity among AIs/ANs.4 This study found that 40% of families living on the Pine Ridge Indian reservation reported experiencing food insecurity, but food insecurity was not linked to obesity among either adults or children.4 Our study is the first to show that a high percentage of low-income urban AIs/ANs are experiencing similar prevalence of food insecurity as AIs/ANs living in rural AI reservation communities.4,5

Our findings add to a growing, but inconsistent, body of literature on the relationship between food insecurity and obesity. Several studies have found that food insecure women are more likely to be obese than food secure women,9–13 but others have not confirmed this relationship39–41 or its persistence over time.42,43 It is also unclear why the relationship between food insecurity and obesity is not consistently observed in men or children.35,44–50 These inconsistencies may be partially due to differences in the measurement of food insecurity. Most studies have used a form of the 18-item HFSSM,22 which assesses 4 levels of food security: high food security, marginal food security, low food security, and very low food security. However, some studies assess food insufficiency, a related concept, with a single question or use alternate instruments.51 For example, one study comparing the accuracy of the HFSSM with the face-valid measures adapted from the Radimer/Cornell measure52 and Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project53 among a group of racially and ethnically diverse Hawaiians found that 85% of the households were classified as food secure by the HFSSM and only 78% were classified as food secure with each of the other food security measures assessed.54

The inconsistent observations regarding food insecurity and obesity could also be explained by variation in the association by race and ethnicity. A recent study among Hispanic women illustrated this point: food insecurity was associated with obesity using a 10-item scale, but food insufficiency was unrelated to obesity.20 Another study of Californian adults found that very low food security was associated with a higher prevalence of obesity among Hispanic men and women and multiracial men but not among non-Hispanic whites, African Americans, Asians, or multiracial women.9 Congruent with these findings, we found that, when using the 3-level measure, Hispanic white women with very low food security were significantly more likely to be obese than their food secure counterparts. Thus, both choice of instrument and race and ethnicity may influence the links between food insecurity and obesity.

The one published study examining the appropriateness of the HFSSM with AIs/ANs reported that, though AIs/ANs had higher levels of food insecurity than non-AIs/ANs as measured by the HFSSM, the magnitude of the differences depended on the choice of measure and on the set of food insecurity questions being asked.24 The study suggests that cultural differences may play a role in the ways in which AIs/ANs and non-AIs/ANs respond to food insecurity questions. For example, AIs/ANs may have larger households in comparison to non-AIs/ANs, which may increase the probability of responding affirmatively to food insecurity questions.24 Additionally, the HFSSM defines food insecurity based on financial constraints and does not measure inadequate food intakes based on limited mobility that prevents travel to purchase food, as is the case in many rural and reservation communities.3,8 These households would not be counted as food insecure by the HFSSM unless they also perceived their food inadequacy as being due to inadequate financial resources.24 Further, AIs/ANs may have different perceptions as to what constitutes an acceptable level of food intake when compared with non-AIs/ANs.24

This study has several limitations. First, all of our participants were residents of California; therefore, our results may not be generalizable to other parts of the country. Nonetheless, this is the first report on the prevalence of food insecurity and the relationship between food insecurity and obesity among a random sample of AIs/ANs. Second, because of our cross-sectional design it not possible to understand the temporal relationships between food insecurity and obesity. Third, our obesity measure was based on self-reported height and weight rather than actual measurement. Although self-reported BMI is typically biased toward underreporting of weight,55 one study that collected both self-reported and measured heights and weights found that the relationship between food insecurity and obesity was more pronounced when using the self-reported measures.56 Lastly, the time of the year individuals are surveyed may influence the prevalence of food insecurity: Hispanic households report experiencing more food insecurity in the winter than in the summer.57

Future studies must design more intensive measures that capture the extent, depth, and severity of food insecurity within AI/AN communities to determine whether those factors play a role in obesity and other health disparities.24 Studies must also examine the overall food environments in AI/AN communities, including the number and type of food outlets, as well as the social eating patterns a community’s members,58,59 which has been shown to contribute to obesity disparities.17,59–67 The mechanisms by which the food environment contribute to food insecurity and individual eating behavior are unknown,17,60,68–70 and even less is known about the food environments in Native American communities,3,8,71 despite rates of obesity (31.2%) and type 2 diabetes (8.5%) that exceed those of non-Hispanic whites (18.5% and 6.6%).72,73 Studies show that reservations and rural tribal areas lack access to food stores, and healthy foods within those stores,3,8,71 and the measures of food insecurity must be amended to capture the problem in these communities. Additionally, studies show that AIs/ANs living in urban areas also report limited access to healthy food;74–76 thus, studies must examine differences among AI/AN communities in diverse geographic settings.

In conclusion, more research on the role of food insecurity is needed to untangle the relationships between food insecurity, obesity, and race and ethnicity. We know little on how social, economic, and institutional factors within food environments—not only for AIs/ANs but for all racial and ethnic groups—contribute to diet-related disparities across populations. Perhaps of greatest relevance for our country’s public health, food insecurity is common among low-income households and could undermine the potential effectiveness of healthy diet and nutrition interventions and programs, contributing to widening diet-related health disparities.19

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Cancer Institute grants U54 CA153498 (Native People for Cancer Control: A Community Networks Program), P50CA148110 (Collaborative to Improve Native Cancer Outcomes, a Center for Native Population Health Disparities), and P30 AG15292 (Native Elder Research Center, a Resource Center for Minority Aging Research).

Footnotes

[Supplemental materials are available for this article. Go to the publisher’s online edition of Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition to view the free supplemental file: Supplemental Tables.doc.].

References

- 1.Anderson SA. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J Nutr. 1990;120(suppl):1555–1600. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.suppl_11.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Agriculture. Food security in the United States. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/foodsecurity/stats_graphs.htm-food_secure. Accessed January 15, 2012.

- 3.Blue Bird Jernigan V, Salvatore AL, Styne DM, Winkleby M. Addressing food insecurity in a Native American reservation using community-based participatory research. Health Educ Res. 2011;27(4):645–655. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer KW, Widome R, Himes JH, et al. High food insecurity and its correlates among families living on a rural american Indian reservation. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown B, Noonan C, Nord M. Prevalence of food insecurity and health-associated outcomes and food characteristics of Northern Plains Indian households. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2007;1(4):37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henchy G, Cheung M, Weill J. WIC in Native American Communities: Building a Healthier America. Washington, DC: Food Research and Action Center; 2000. p. RC023270. (Report Summary). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray EB, Holben DH, Holcomb JP. Food security status and produce intake behaviors, health status, and diabetes risk among women with children living on a Navajo reservation. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2012;7(1):91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connell M, Buchwald DS, Duncan GE. Food access and cost in American Indian communities in Washington State. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1375–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams EJ, Grummer-Strawn L, Chavez G. Food insecurity is associated with increased risk of obesity in California women. J Nutr. 2003;133:1070–1074. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinour LM, Bergen D, Yeh M-C. The food insecurity–obesity paradox: a review of the literature and the role food stamps may play. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1952–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin KS, Ferris AM. Food insecurity and gender are risk factors for obesity. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(1):31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Townsend MS, Peerson J, Love B, Achterberg C, Murphy SP. Food insecurity is positively related to overweight in women. J Nutr. 2001;131:1738–1745. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.6.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson CM. Nutrition and health outcomes associated with food insecurity and hunger. J Nutr. 1999;129(suppl):521S–524S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.521S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gucciardi E, Vogt JA, DeMelo M, Stewart DE. Exploration of the relationship between household food insecurity and diabetes in Canada. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2218–2224. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seligman H, Bindman A, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya A, Kushel M. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1018–1023. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cade J, Upmeier H, Calvert C, Greenwood D. Cost of a healthy diet: analysis from the 1K Women’s Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 1999;2:505–512. doi: 10.1017/s1368980099000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morland K, Wing S, Roux AD. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1761–1768. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swinburn BA, Caterson I, Seidell JC, James WPT. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:123–146. doi: 10.1079/phn2003585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140:304–310. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaiser LL, Townsend MS, Melgar-Quionez HR, Fujii ML, Crawford PB. Choice of instrument influences relations between food insecurity and obesity in Latino women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1372–1378. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolfe WS, Olson CM, Kendall A, Frongillo EA., Jr Hunger and food insecurity in the elderly: its nature and measurement. J Aging Health. 1998;10:327–350. doi: 10.1177/089826439801000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derrickson JP, Fisher AG, Anderson JE. The core food security module scale measure is valid and reliable when used with Asians and Pacific Islanders. J Nutr. 2000;130:2666–2674. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.11.2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gundersen C. Measuring the extent, depth, and severity of food insecurity: an application to American Indians in the USA. J Popul Econ. 2008;21:191–215. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dixon LB, Winkleby MA, Radimer KL. Dietary intakes and serum nutrients differ between adults from food-insufficient and food-sufficient families: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J Nutr. 2001;131:1232–1246. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JS, Frongillo EA. Nutritional and health consequences are associated with food insecurity among US elderly persons. J Nutr. 2001;131:1503–1509. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarasuk VS, Beaton GH. Women’s dietary intakes in the context of household food insecurity. J Nutr. 1999;129:672–679. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kendall A, Olson CM, Frongillo EA., Jr Relationship of hunger and food insecurity to food availability and consumption. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00271-4. quiz 1025–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dave JM, Evans AE, Saunders RP, Watkins KW, Pfeiffer KA. Associations among food insecurity, acculturation, demographic factors, and fruit and vegetable intake at home in Hispanic children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:697–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reaven GM. Hypothesis: muscle insulin resistance is the (“not-so”) thrifty genotype. Diabetologia. 1998;41:482–484. doi: 10.1007/s001250050933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravelli AC, van der Meulen JH, Michels RP, et al. Glucose tolerance in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. Lancet. 1998;351(9097):173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basiotis P, Lino M. Food insufficiency and prevalence of overweight among adult women. Nutr Insights. 2002;26:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drewnowski A. Obesity and the food environment: dietary energy density and diet costs. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finney Rutten LJ, Yaroch AL, Colón-Ramos U, Johnson-Askew W, Story M. Poverty, food insecurity, and obesity: a conceptual framework for research, practice, and policy. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2010;5:403–415. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhattacharya J, Currie J, Haider S. Poverty, food insecurity, and nutritional outcomes in children and adults. J Health Econ. 2004;23:839–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Bureau of the Census. Fact Sheet: American Indians and Alaska Natives. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. California Health Interview Survey. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2009. (CHIS Methodology Series). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blumberg SJ, Bialostosky K, Hamilton WL, Briefel RR. The effectiveness of a short form of the Household Food Security Scale. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1231–1234. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitaker RC, Sarin A. Change in food security status and change in weight are not associated in urban women with preschool children. J Nutr. 2007;137:2134–2139. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.9.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Evenson KR. Self-reported overweight and obesity are not associated with concern about enough food among adults in New York and Louisiana. Prev Med. 2004;38(2):175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olson CM, Strawderman MS. The relationship between food insecurity and obesity in rural childbearing women. J Rural Health. 2008;24:60–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones SJ, Frongillo EA. Food insecurity and subsequent weight gain in women. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(2):145–151. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007246737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones SJ, Frongillo EA. The modifying effects of Food Stamp Program participation on the relation between food insecurity and weight change in women. J Nutr. 2006;136:1091–1094. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.4.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jyoti DF, Frongillo EA, Jones SJ. Food insecurity affects school children’s academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. J Nutr. 2005;135:2831–2839. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.12.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA., Jr Low family income and food insufficiency in relation to overweight in US children: is there a paradox? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.10.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gundersen C, Garasky S, Lohman BJ. Food insecurity is not associated with childhood obesity as assessed using multiple measures of obesity. J Nutr. 2009;139:1173–1178. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.105361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhargava A, Jolliffe D, HOWARD LL. Socio-economic, behavioural and environmental factors predicted body weights and household food insecurity scores in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:438–444. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508894366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feinberg E, Kavanagh PL, Young RL, Prudent N. Food insecurity and compensatory feeding practices among urban black families. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e854–e860. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casey PH, Szeto K, Lensing S, Bogle M, Weber J. Children in food-insufficient, low-income families: prevalence, health, and nutrition status. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:508–514. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitaker RC, Orzol SM. Obesity among US urban preschool children: relationships to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:578–584. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.6.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Larson N, Story M. Food Insecurity and Risk for Obesity Among Children and Families: Is There a Relationship? Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kendall A, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Validation of the Radimer/Cornell measures of hunger and food insecurity. J Nutr. 1995;125:2793–2801. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.11.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wehler CA, Scott RI, Anderson JJ. The Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project: a model of domestic hunger and demonstration project in Seattle, Washington. J Nutr Educ. 1992;24(1 supplement 1):29S–35S. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Derrickson JP, Fisher AG, Anderson JEL, Brown AC. An assessment of various household food security measures in Hawaii has implications for national food security research and monitoring. J Nutr. 2001;131:749–757. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keith SW, Fontaine KR, Pajewski NM, Mehta T, Allison DB. Use of self-reported height and weight biases the body mass index–mortality association. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:401–408. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyons AA, Park J, Nelson CH. Food insecurity and obesity: a comparison of self-reported and measured height and weight. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:751–757. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaiser LL, Melgar-Quinonez H, Townsend MS, et al. Food insecurity and food supplies in Latino households with young children. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2003;35(3):148–153. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19:330–333. ii. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Kaufman JS, Jones SJ. Proximity of supermarkets is positively associated with diet quality index for pregnancy. Prev Med. 2004;39:869–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Franco M. Measuring availability of healthy foods: agreement between directly measured and self-reported data. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;10:1037–1044. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Powell LM, Slater S, Mirtcheva D, Bao Y, Chaloupka FJ. Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang M, Gonzalez A, Ritchie L, Winkleby M. The neighborhood food environment: sources of historical data on retail food stores. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, James SA, Bao S, Wilson ML. Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:660–667. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Jacobs DR., Jr Associations of the local food environment with diet quality—a comparison of assessments based on surveys and geographic information systems: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:917–924. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang MC, Cubbin C, Ahn D, Winkleby MA. Changes in neighbourhood food store environment, food behaviour and body mass index, 1981–1990. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:963–970. doi: 10.1017/S136898000700105X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Glanz K, Yaroch AL. Strategies for increasing fruit and vegetable intake in grocery stores and communities: policy, pricing, and environmental change. Prev Med. 2004;39(suppl 2):75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee H. The role of local food availability in explaining obesity risk among young school-aged children. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1193–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.An R, Sturm R. School and residential neighborhood food environment and diet among California youth. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gittelsohn J, Rowan M. Preventing diabetes and obesity in American Indian communities: the potential of environmental interventions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1179S–1183S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.003509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mokdad A, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the united states. JAMA. 2001;286:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jernigan VBB, Duran B, Ahn D, Winkleby M. Changing patterns in health behaviors and risk factors related to cardiovascular disease among American Indians and Alaska natives. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:677–683. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.164285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miller P. Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations. Helena, MT: The Montana Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services and The Montana Hunger Coalition; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dillinger T, Jett S, Macri M, Grivetti L. Feast or famine? Supplemental food programs and their impact on two American Indian communities in California. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 1999;50:173–187. doi: 10.1080/096374899101210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Halpern P. Obesity and American Indians/Alaska Natives. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.