Abstract

Regulatory B cells that secrete IL-10 (IL-10+ Bregs) represent a suppressive subset of the B cell compartment with prominent anti-inflammatory capacity, capable of suppressing cellular and humoral responses to cancer and vaccines. B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) is a key regulatory molecule in IL-10+ Breg biology with tightly controlled serum levels. However, BLyS levels can be drastically altered upon chemotherapeutic intervention. We have previously shown that serum BLyS levels are elevated, and directly associated, with increased antigen-specific antibody titers in patients with glioblastoma (GBM) undergoing lymphodepletive temozolomide chemotherapy and vaccination. In this study, we examined corresponding IL-10+ Breg responses within this patient population and demonstrate that the IL-10+ Breg compartment remains constant before and after administration of the vaccine, despite elevated BLyS levels in circulation. IL-10+ Breg frequencies were not associated with serum BLyS levels, and ex vivo stimulation with a physiologically relevant concentration of BLyS did not increase IL-10+ Breg frequency. However, BLyS stimulation did increase the frequency of the overall B cell compartment and promoted B cell proliferation upon B cell receptor engagement. Therefore, using BLyS as an adjuvant with therapeutic peptide vaccination could promote humoral immunity with no increase in immunosuppressive IL-10+ Bregs. These results have implications for modulating humoral responses in human peptide vaccine trials in patients with GBM.

Keywords: BLyS, BAFF, Bregs, Lymphopenia, GBM, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Regulatory B cells (IL-10+ Bregs) play an immunosuppressive role in mouse models for autoimmunity and cancer [1–5]. IL-10+ Bregs downregulate effector T cell responses through the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and through cell-to-cell contact [1, 4, 6] and have been shown to promote cancer progression in murine models by upregulating immunosuppressive cell subsets such as regulatory T cells (Tregs) [7]. However, the regulation of these cells, especially in human systems, is not well understood [8, 9]. B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) is a B cell homeostatic cytokine that promotes differentiation and survival of B cells and has been linked to the promotion of IL-10+ Bregs in preclinical and clinical studies [10–13]. Examination of BLyS and IL-10+ Bregs in the context of vaccination may provide important information on the induction of potentially immunosuppressive and detrimental IL-10+ Bregs responses.

Our phase II trial of rindopepimut®, an epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII) vaccine consisting of a 14-amino acid peptide containing the EGFRvIII mutation (PEPvIII, H-Leu-Glu–Glu-Lys–Lys-Gln-Asn-Tyr-Val-Val-Thr-Asp-His-Cys-OH) chemically conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) for the treatment of patients with glioblastoma (GBM) has shown a survival benefit in a multicenter, single-arm phase II clinical trial (ACT-III) [14], likely through an antibody-dependent mechanism. In newly diagnosed patients with GBM, this vaccine was administered with the standard-of-care (SOC) lymphodepleting chemotherapeutic alkylating agent temozolomide (TMZ) and these patients developed supraphysiological EGFRvIII-specific antibody titers [15–18]. Further analysis revealed elevated serum BLyS levels (likely due to the lymphodepletive effects of TMZ), and these BLyS levels directly correlated with vaccine-induced immunoglobulin levels [19]. This clinical observation is supported by preclinical studies demonstrating a role for BLyS in the promotion of humoral responses [20, 21].

In this study, we examine the association of human IL-10+ Bregs with serum BLyS levels in the context of SOC TMZ treatment and PEPvIII-KLH vaccination in patients with GBM [22–24]. Since BLyS levels are elevated in the context of TMZ-induced lymphopenia, we hypothesized that BLyS stimulation may enhance IL-10+ Bregs frequencies in these patients and impede the ability to achieve maximal anti-tumor immune responses [19, 25, 26]. Our studies demonstrated that after serial PEPvIII-KLH vaccination in the context lymphopenia, the frequency of IL-10+ Bregs in GBM patients did not significantly change. In addition, there was no association between the size of the IL-10+ Breg compartment and BLyS serum levels. Further in vitro studies revealed that the frequency of IL-10+ Bregs did not increase upon stimulation with physiologically comparable BLyS levels. However, BLyS enhanced the proliferation and increased the frequency of the global B cell compartment. Taken together, these data suggest that using BLyS as an adjuvant with therapeutic peptide vaccination may not trigger IL-10+ Breg expansion and instead promotes the proliferation of activated B cells and humoral immunity. These results implicate BLyS as a novel adjuvant for enhancing humoral responses in human peptide vaccine trials.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Cryopreserved patient samples were collected by blood draw or leukapheresis from the ACT-II trial, as described in [15]. Briefly, adults with newly diagnosed GBM who had gross total resection of their EGFRvIII-positive tumor and a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) score of ≥80 with no radiographic evidence of progression after radiation therapy were eligible for vaccination. The trial design and informed consent were approved by the FDA (under BB-IND-9944) and the local institutional review boards [15–17]. After tumor resection and conformal external beam radiotherapy (XRT) with concurrent TMZ at a targeted dose of 75 mg/m2, informed consent was obtained. The initial 3 vaccinations of a 14-mer peptide conjugated to KLH were given every two weeks starting within 6 weeks of completing radiation [15, 16]. Subsequent vaccines were given until clinical or radiographic evidence of tumor progression or death. Patients were assigned to receive TMZ at a targeted dose of 100 mg/m2 for the first 21 days of a 28-day cycle (n = 8).

Patient samples selected for analyses were taken at vaccine 1, prior to any vaccination or TMZ treatment at 100 mg/m2 (Pre), and at a patient variable post-vaccination time point that was selected to occur after patient peak serum BLyS levels and near peak anti-EGFRvIII antibody titers (post) [19]. Table 1 includes the serum BLyS levels of GBM patients at the time of IL-10+ Breg analysis. These time points were selected based on our hypothesis that serum BLyS elevation will directly translate into an enhancement of IL-10+ Breg frequency, and based on our available clinical samples. Normal donor samples were collected at Duke University Medical Center.

Table 1.

BLyS serum levels of GBM patients at the time of IL-10+ Breg analysis

| All patients | BLyS serum levels (pg/ml) | BLyS (fold increase) |

|---|---|---|

| ACTII(B6) | 1357 | 1.346 |

| ACTII(B7) | 1786 | 1.772 |

| ACTII(B10) | 2397 | 2.378 |

| ACTII(B11) | 1372 | 1.361 |

| ACTII(B12) | 1688 | 1.675 |

| ACTII(B14) | 1439 | 1.428 |

| ACTII(B15) | 1386 | 1.375 |

| ACTII(B17) | 1337 | 1.326 |

Ex vivo evaluation of IL-10 competency

In accordance with the protocols adopted from Iwata et al. [8], and with the studies from Khoder et al. [9], peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were utilized for these studies because of the limited clinical sample availability. PBMCs were rested overnight (o/n) in RPMI Medium 1640 with GlutaMAX™-I (Gibco) plus 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, GemCell™). Cells were then harvested and plated at 4.0 × 106 cells/ml in 48-well plate for 43 h in media supplemented with 1 µg/ml CD40L (R&D Systems) and 10 µg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Sigma-Aldrich catalog no. L4391). They were subsequently stimulated for 5 h with 50 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, Sigma-Aldrich), 1 µg/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 µg/ml LPS, and 1ul/ml of Brefeldin A (BFA, BD Biosciences GolgiPlug™—Protein Transport Inhibitor).

Cells were washed and stained with monoclonal fluorophore-conjugated antibodies for the following cell surface markers: extracellular peridinin chlorophyll protein complex (PerCP)-anti-CD19 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-anti-CD14 as well as intracellular Allophycocyanin (APC)-anti-IL-10. Intracellular staining was performed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Kit (BD Biosciences) as described by manufacturer.

Ex vivo BLyS-sensitivity assay

In order to examine cell sensitivity to BLyS, cells were stimulated in a similar protocol as used for the determination of IL-10 competency. BLyS (2000 ng/ml; B cell-activating factor (BAFF), R&D Systems) was added to the initial stimulation media as described above, and 4.0 × 106 cells/ml rested PBMCs were stimulated for 67 h in a 48-well plate before being transferred for 5 h to media containing 50 ng/ml PMA (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 µg/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 µg/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 ul/ml of BFA (BD Biosciences). The intracellular staining was performed identically as described above.

B cell proliferation assay

To assess the B cell proliferative response to BLyS stimulation, we stained normal donor PBMCs with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Life Technologies), a fluorescent stain used to track cell proliferation, and stimulated with goat anti-immunoglobulin (Ig)M (Southern Biotech) and BLyS (R&D; 2000 ng/ml) in a 48-well plate (BD Falcon) for 72 h. The cells were then stained for CD19 (PerCP) and analyzed for proliferation by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Based on previous studies demonstrating the impact of BLyS on increasing the IL-10+ Breg frequency among B cells [10–13], our a priori hypothesis was that due to the elevated serum BLyS levels experienced in our GBM patient population [19], this effect will directly translate into an enhancement of IL-10+ Breg frequency within the B cells compartment. Since this hypothesis is unidirectional, a paired, one-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare IL-10+ Bregs frequency in pre- and post-vaccination samples. A Pearson linear regression was used to assess associations and statistical significance when examining associations with various other trial parameters. An unpaired, one-tailed Student’s t test was used when comparing BLyS-induced IL-10+ Bregs frequencies in GBM patients to normal donor samples. Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05. All statistical analysis was completed in GraphPad Prism 5.00.

Results

The frequency of IL-10+ Bregs is unchanged following TMZ and peptide vaccine treatment

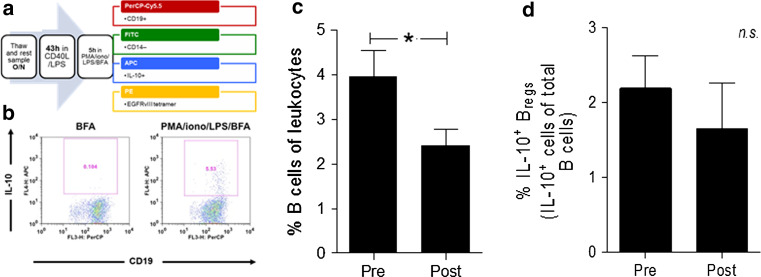

To understand the effect of tumor-specific peptide vaccination and TMZ-induced lymphopenia, on IL-10-secreting IL-10+ Bregs and based on the hypothesis that serum BLyS elevation will directly translate into an enhancement of IL-10+ Breg frequency, we examined PBMCs from cryopreserved samples from PEPvIII-KLH-vaccinated GBM patients undergoing lymphodepletive TMZ treatment, utilizing a functional IL-10+ Breg assay adopted from Iwata et al. [8] and Khoder et al. [9] depicted in Fig. 1a, b. IL-10+ Breg frequency was analyzed at vaccine 1, prior to any vaccination or TMZ treatment at 100 mg/m2 (Pre), and was also analyzed post-vaccination at a time point chosen on a patient by patient basis that was selected to occur after peak serum BLyS levels and near peak anti-EGFRvIII antibody titers (post) [19]. Table 1 includes the serum BLyS levels of GBM patients at the time of IL-10+ Breg analysis. In accordance with previous studies published from this patient population [15], analysis of the B cell population demonstrated an expected reduction in the frequency of B cells (Fig. 1c; *p = 0.0466). This reduction is largely attributed to the lymphodepletive effect of TMZ chemotherapy [15]. Of interest, while the B cell frequency was reduced, there was no significant difference in IL-10+ Breg frequency between these time points (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

IL-10+ Bregs frequency remains constant in glioblastoma patients undergoing TMZ and peptide vaccine. a PBMCs were rested overnight (o/n) in media (RPMI Medium 1640 with GlutaMAX™-I plus 10 % FBS). Cells were harvested and stimulated in a 48-well plate at 4.0 × 106 cells/ml for 43 h in media supplemented with 1 µg/ml CD40L and 10 µg/ml LPS. They were subsequently stimulated for 5 h in media with 50 ng/ml PMA, 1 µg/ml ionomycin, 10 µg/ml LPS, and 1× Brefeldin A (BFA) before being stained for CD19, CD14, IL-10, and, in some experiments, the EGFRvIII tetramer. b A representative flow cytometry sample from a patient sample is shown, compared to the appropriate negative control. c In the same experiments, the frequency of total B cells was found to decrease over the course of vaccination (*p = 0.0466). d No significant difference was observed in the frequency of IL-10+ Bregs in patient PBMC samples (N = 8) from the ACT-II trial (p = 0.20165). Paired one-tailed t test analyses were used to determine statistical significance (*p < 0.05)

The frequency of IL-10+ Bregs does not associate with anti-EGFRvIII antibody titers or patient survival

Published data indicate a potential role for IL-10+ Breg in regulating humoral and cellular responses to vaccines as well as a regulatory role in immunosuppression and cancer progression. We therefore decided to analyze the relationship of IL-10+ Breg frequency with peak anti-EGFRvIII antibody titers and patient survival outcomes. We found that post-vaccination IL-10+ Breg frequency is not related to peak anti-EGFRvIII antibody titers (Fig. 2a; r 2 = 0.03185; p = 0.6724). Also, there does not appear to be any association with overall patient survival (Fig. 2b; r 2 = 0.06793; p = 0.5330) progression-free survival, or time to radiographic progression of disease (Fig. 2c; r 2 = 0.09114; p = 0.4674) measured in months (mo).

Fig. 2.

The frequency of IL-10+ Bregs is not associated with anti-EGFRvIII Ig titer or patient survival. Associations between IL-10+ Breg frequencies and (a) patient peak serum anti-EGFRvIII titer (r 2 = 0.03185; p = 0.6724), (b) patient overall survival in months (mo) (r 2 = 0.06793; p = 0.5330), and (c) patient progression-free survival in months (r 2 = 0.09114; p = 0.4674) were evaluated. The Pearson correlation statistics were used to determine statistical significance

BLyS elevation does not affect the frequency of IL-10+ Bregs but increases the frequency and proliferation of B cells

Since previous preclinical studies have demonstrated a role for BLyS in promoting IL-10+ Breg frequencies, we decided to evaluate whether BLyS serum levels were associated with IL-10+ Breg frequencies in our GBM patients at time of IL-10+ Breg analysis (Table 1). Therefore, we compared IL-10+ Breg frequencies to corresponding patient BLyS serum levels. There was no significant association (Fig. 3a, R 2 = 0.3253; p = 0.1399) between IL-10+ Breg and patient BLyS serum levels. Since our previous findings suggested a strong relationship between serum BLyS and B cell activity [19], we investigated these seemingly incongruous results by stimulating healthy, normal donor PBMC samples with BLyS in addition to ex vivo B cell receptor stimulation before intracellular IL-10 staining. We found no significant difference in IL-10+ Breg frequency when cells were cultured with physiologically relevant levels of BLyS (Fig. 3b; p = 0.4882). However, both the frequency of B cells (Fig. 3c; *p = 0.0283) and the level of proliferation as determined by carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) did increase significantly (Fig. 3d; *p = 0.0284). Thus, BLyS does not appear to affect the IL-10+ Breg compartment in ex vivo samples at the time of peak antibody titer or in vitro healthy donor samples, but does increase global B cell frequency and proliferation.

Fig. 3.

BLyS elevation does not impact frequency of IL-10+ Bregs, but significantly impacts B cell levels and proliferation. a There was no significant relationship observed between the frequency of IL-10+ Bregs and patient serum BLyS levels at the time of IL-10+ Bregs analysis (R 2 = 0.3253; p = 0.1399). Dotted line represents the average serum levels of BLyS in normal donors. b Ex vivo experiments with healthy donor samples found no significant change in the frequency of IL-10+ Bregs in healthy donor PBMC samples in the context of soluble BLyS (2000 ng/ml). c However, ex vivo experiments demonstrated a significant change in the frequency of B cells in healthy donor PBMC samples upon soluble BLyS addition (p = 0.0283). d B cells stimulated with anti-IgM and BLyS proliferated significantly more, as measured by a CFSE proliferation assay (p = 0.0284). Paired one-tailed t test analysis was used to determine statistical significance (*p < 0.05)

Discussion

In the context of tumor-specific vaccination during lymphodepletive TMZ chemotherapy in patients with GBM, we found that IL-10+ Breg frequency was unchanged despite elevated BLyS levels at the time of analysis. While this therapy elicits robust production of anti-EGFRvIII antibodies and results in an increased overall survival when compared to historical controls [14, 15, 24], IL-10+ Breg frequency was not associated with peak anti-EGFRvIII antibody titers, patient survival outcomes, or BLyS levels. These results were unexpected due the mouse and human literature demonstrating a link between BLyS levels and IL-10+ Breg promotion [10–12].

However, recent studies suggest that IL-10+ Breg subsets may not have the same activation-program response to BLyS observed in the greater CD19+ B cell compartment [27], which could account for the IL-10+ Breg dynamics observed in our study. Another important point is the utilization of rested PBMCs for the IL-10+ Breg assay. Many studies utilize purified B cells in stimulation assays in order to specifically stimulate the pure B cell population and to determine the IL-10+ Breg fraction [8, 28]. As we utilized PBMCs, there is the possibility of an indirect B cell stimulation by factors secreted by non-B cell subsets which might contribute to IL-10+ Breg differentiation. Caveats of this study are the limited availability of the clinical samples as well as the decreased lymphocyte counts within these samples due to patient treatment with lymphodepletive TMZ chemotherapy. However, a recent study by Khoder et al. [9] demonstrated that IL-10+ Bregs can be effectively examined from whole PBMCs. Therefore, we believe that our results represent the normal physiology of the IL-10+ Breg compartment and that this compartment is not increased under elevated levels of serum BLyS.

IL-10+ Bregs represent a suppressive compartment of the B cell lineage. While several markers exist to identify different Breg subsets in humans, the reported phenotype of these cells varies between studies [8, 28, 29]. A B cell population with the phenotype CD19+ CD24high CD38high has been shown to secrete large amounts of IL-10 upon stimulation through CD40 [28]. Another human Breg cell subset equivalent to murine B10 cells, which expresses CD24 and the memory-related marker CD27 [8, 30], has also been identified. While different subsets exist for IL-10+ Bregs in both humans and mice, the IL-10+ Breg subset evaluated in this study universally displays the phenotypic markers of CD19+ CD24high CD38high. Therefore, our study focuses on the evaluation of CD19+ CD24high CD38high IL-10+ Bregs, which are largely considered to be the main contributors of IL-10 secretion and regulation. Our study demonstrates that this population might not be as sensitive to the homeostatic cytokine BLyS as previously expected from studies that demonstrate the role of BLyS on IL-10+ Breg homeostasis. It remains to be elucidated whether another distinct regulatory B cell subset characterized by CD1dhigh CD5+ expression, which was previously determined to be sensitive to BLyS-induced expansion [10–13], will be elevated in these patients with elevated serum BLyS levels.

These data indicate that in the context of TMZ-induced lymphopenia and humoral immunity-targeting vaccines, IL-10+ Bregs may not be as responsive to BLyS as nonregulatory B cell subsets. These discrepancies may pertain to differences in BLyS receptor expression or the expression of intracellular adaptor molecules known to regulate receptor-mediated IL-10 induction [13]. Alternatively, in response to BLyS, serial vaccinations with PEPvIII-KLH-inducing anti-EGFRvIII immunoglobulins may differentially affect activation and maturation between regulatory and nonregulatory B cell subsets. Unlike the Treg compartment [31–34], our current and previous findings [19] indicate that there may be diminished IL-10+ Breg responses to tumor-specific vaccines.

These results have implications for interpreting and more effectively modulating humoral responses in human peptide vaccine trials. By delineating the interplay between BLyS, IL-10+ Bregs, and antigen-specific humoral responses, we may ultimately be able to deliver tangible benefits for patients with refractory tumors (i.e., GBM) expressing tumor-specific surface antigens. Importantly, our findings indicate that IL-10+ Bregs may not be a regulatory barrier in the use of BLyS as a humoral adjuvant for vaccine-based cancer immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tracy A. Chewning for her assistance in the preparation of grant applications supporting these studies.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: Specialized Research Center on Primary Tumors of the Central Nervous System P50 NS020023-28 and 3R01-CA-135272-02S1 supplement for Brain Tumor Stem Cell R01, 5P50-NS020023-29, 5R01-CA135272-02S1, and 5R01-CA134844-03. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Authorship contributions

Anirudh Saraswathula designed, performed, and analyzed data and co-wrote manuscript; Elizabeth A. Reap designed and analyzed data and co-wrote manuscript; Bryan D. Choi designed initial experiments and co-wrote manuscript; Robert J. Schmittling performed experiments and analyzed data; Pamela K. Norberg provided critical samples for experimentation and analyzed data; Elias J. Sayour co-wrote the manuscript; James E. Herndon II, and Patrick Healy provided statistical expertise and analysis; Kendra L. Congdon analyzed data and co-wrote manuscript; Gerald E. Archer provided clinical samples and helped design experiments; Luis Sanchez-Perez designed, analyzed, and co-wrote manuscript, and John H. Sampson provided funding.

Abbreviations

- APC

Allophycocyanin

- Bregs

Regulatory B cells

- BAFF

B cell-activating factor

- BFA

Brefeldin A

- BLyS

B lymphocyte stimulator

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- EGFRvIII

Epidermal growth factor receptor variant III

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- IL-10

Interleukin-10

- IL-10+ Bregs

Regulatory B cells that secrete IL-10

- KLH

Keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- KPS

Karnofsky performance status

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- mo

Months

- o/n

Overnight

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PEPvIII

Peptide containing the EGFRvIII mutation

- PerCP

Peridinin chlorophyll protein complex

- PMA

Phorbol myristate acetate

- SOC

Standard of care

- Tregs

Regulatory T cells

- TMZ

Temozolomide

- XRT

External beam radiotherapy

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Employment or leadership position: none; consultant or advisory role: John H. Sampson, Celldex Therapeutics©; stock ownership: none; honoraria: none; research funding: John H. Sampson, Celldex Therapeutics©; expert testimony: none; other remuneration: John H. Sampson received funding from license fees paid by Celldex Therapeutics©. All other authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Anirudh Saraswathula and Elizabeth A. Reap have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Candando KM, Lykken JM, Tedder TF. B10 cell regulation of health and disease. Immunol Rev. 2014;259:259–272. doi: 10.1111/imr.12176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KM, Ishigami T, Hata D, Yamaoka K, Mayumi M, Mikawa H. Regulation of cell division of mature B cells by ionomycin and phorbol ester. J Immunol. 1992;148:1797–1803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsushita T, Tedder TF. Identifying regulatory B cells (B10 cells) that produce IL-10 in mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;677:99–111. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-869-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Haas KM, Poe JC, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. A regulatory B cell subset with a unique CD1dhiCD5+phenotype controls T cell-dependent inflammatory responses. Immunity. 2008;28:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz SI, Parker D, Turk JL. B-cell suppression of delayed hypersensitivity reactions. Nature. 1974;251:550–551. doi: 10.1038/251550a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessel A, Haj T, Peri R, Snir A, Melamed D, Sabo E, Toubi E. Human CD19(+)CD25(high) B regulatory cells suppress proliferation of CD4(+) T cells and enhance Foxp3 and CTLA-4 expression in T-regulatory cells. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:670–677. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olkhanud PB, Damdinsuren B, Bodogai M, Gress RE, Sen R, Wejksza K, Malchinkhuu E, Wersto RP, Biragyn A. Tumor-evoked regulatory B cells promote breast cancer metastasis by converting resting CD4(+) T cells to T-regulatory cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3505–3515. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwata Y, Matsushita T, Horikawa M, et al. Characterization of a rare IL-10-competent B-cell subset in humans that parallels mouse regulatory B10 cells. Blood. 2011;117:530–541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoder A, Sarvaria A, Alsuliman A, et al. Regulatory B cells are enriched within the IgM memory and transitional subsets in healthy donors but are deficient in chronic GVHD. Blood. 2014;124:2034–2045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-571125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang M, Sun L, Wang S, Ko KH, Xu H, Zheng BJ, Cao X, Lu L. Novel function of B cell-activating factor in the induction of IL-10-producing regulatory B cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3321–3325. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yehudai D, Snir A, Peri R, Halasz K, Haj T, Odeh M, Kessel A. B cell-activating factor enhances interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 production by ODN-activated human B cells. Scand J Immunol. 2012;76:371–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu LG, Wu M, Hu J, Zhai Z, Shu HB. Identification of downstream genes up-regulated by the tumor necrosis factor family member TALL-1. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:410–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu LG, Shu HB. TNFR-associated factor-3 is associated with BAFF-R and negatively regulates BAFF-R-mediated NF-kappa B activation and IL-10 production. J Immunol. 2002;169:6883–6889. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuster J, Lai RK, Recht LD, et al. A phase II, multicenter trial of rindopepimut (CDX-110) in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: the ACT III study. Neuro-oncol. 2015;17:854–861. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sampson JH, Aldape KD, Archer GE, et al. Greater chemotherapy-induced lymphopenia enhances tumor-specific immune responses that eliminate EGFRvIII-expressing tumor cells in patients with glioblastoma. Neuro-oncol. 2011;13:324–333. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampson JH, Heimberger AB, Archer GE, et al. Immunologic escape after prolonged progression-free survival with epidermal growth factor receptor variant III peptide vaccination in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol . 2010;28:4722–4729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampson JH, Archer GE, Mitchell DA, et al. An epidermal growth factor receptor variant III-targeted vaccine is safe and immunogenic in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2773–2779. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heimberger AB, Sampson JH. The PEPvIII-KLH (CDX-110) vaccine in glioblastoma multiforme patients. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:1087–1098. doi: 10.1517/14712590903124346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez-Perez L, Choi BD, Reap EA, et al. BLyS levels correlate with vaccine-induced antibody titers in patients with glioblastoma lymphodepleted by therapeutic temozolomide. Cancer Immunol Immunother: CII. 2013;62:983–987. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1405-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dosenovic P, Soldemo M, Scholz JL, et al. BLyS-mediated modulation of naive B cell subsets impacts HIV Env-induced antibody responses. J Immunol. 2012;188:6018–6026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gor DO, Ding X, Li Q, Sultana D, Mambula SS, Bram RJ, Greenspan NS. Enhanced immunogenicity of pneumococcal surface adhesin A (PsaA) in mice via fusion to recombinant human B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) Biol Direct. 2011;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackay F, Schneider P. Cracking the BAFF code. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:491–502. doi: 10.1038/nri2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodland RT, Schmidt MR, Thompson CB. BLyS and B cell homeostasis. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swartz AM, Li QJ, Sampson JH. Rindopepimut: a promising immunotherapeutic for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Immunotherapy. 2014;6:679–690. doi: 10.2217/imt.14.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neyns B, Tosoni A, Hwu WJ, Reardon DA. Dose-dense temozolomide regimens: antitumor activity, toxicity, and immunomodulatory effects. Cancer. 2010;116:2868–2877. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su YB, Sohn S, Krown SE, et al. Selective CD4+ lymphopenia in melanoma patients treated with temozolomide: a toxicity with therapeutic implications. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:610–616. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garraud O, Borhis G, Badr G, Degrelle S, Pozzetto B, Cognasse F, Richard Y. Revisiting the B-cell compartment in mouse and humans: more than one B-cell subset exists in the marginal zone and beyond. BMC Immunol. 2012;13:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-13-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blair PA, Norena LY, Flores-Borja F, Rawlings DJ, Isenberg DA, Ehrenstein MR, Mauri C. CD19(+)CD24(hi)CD38(hi) B cells exhibit regulatory capacity in healthy individuals but are functionally impaired in systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients. Immunity. 2010;32:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang M, Rui K, Wang S, Lu L. Regulatory B cells in autoimmune diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 2013;10:122–132. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouaziz JD, Calbo S, Maho-Vaillant M, Saussine A, Bagot M, Bensussan A, Musette P. IL-10 produced by activated human B cells regulates CD4(+) T-cell activation in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2686–2691. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sampson JH, Schmittling RJ, Archer GE, et al. A pilot study of IL-2Ralpha blockade during lymphopenia depletes regulatory T-cells and correlates with enhanced immunity in patients with glioblastoma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell DA, Cui X, Schmittling RJ, et al. Monoclonal antibody blockade of IL-2 receptor alpha during lymphopenia selectively depletes regulatory T cells in mice and humans. Blood. 2011;118:3003–3012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-334565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fecci PE, Sweeney AE, Grossi PM, et al. Systemic anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody administration safely enhances immunity in murine glioma without eliminating regulatory T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4294–4305. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fecci PE, Mitchell DA, Whitesides JF, et al. Increased regulatory T-cell fraction amidst a diminished CD4 compartment explains cellular immune defects in patients with malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3294–3302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]