Abstract

Several benign and malignant mesenchymal and meningothelial lesions may preferentially affect or extend into the sinonasal tract. Glomangiopericytoma (GPC, formerly sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma) is a specific tumor with a predilection to the sinonasal tract. Sinonasal tract polyps with stromal atypia (antrochoanal polyp) demonstrate unique histologic findings in the sinonasal tract. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) arises from specialized tissue in this location. Meningioma may develop as direct extension from its intracranial counterpart or as an ectopic tumor. Selected benign mesenchymal tumors may arise in the sinonasal tract and pose a unique differential diagnostic consideration, such as solitary fibrous tumor and GPC or lobular capillary hemangioma and JNA. Although benign and malignant vascular, fibrous, fatty, skeletal muscle, and nerve sheath tumors may occur in this location, this paper focuses on a highly select group of rare benign sinonasal tract tumors with their clinicopathological and molecular findings, and differential diagnosis.

Keywords: Sinonasal tract, Hemangiopericytoma, Angiofibroma, Polyps, Granuloma, Pyogenic, Nerve sheath neoplasms, Diagnosis, Differential, Meningioma, Solitary fibrous tumor

Introduction

Benign mesenchymal and meningothelial lesions uncommonly affect the sinonasal tract, but are frequently a source of difficulty for pathologists. Epithelial lesions are much more common, but may take on a spindled, mesenchymal or biphasic appearance, resulting in further difficulty. Malignant mesenchymal tumors may more commonly be identified in other head and neck locations. This paper specifically discusses rare benign lesions that are unique to the sinonasal tract, such as a glomangiopericytoma (GPC, sinonasal tract hemangiopericytoma), antrochoanal polyp (ACP or inflammatory polyp with stromal atypia), and juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA), while solitary fibrous tumor (SFT), lobular capillary hemangioma (LCH) and meningioma may develop in this location, but are often unexpected or may have overlapping features with other lesions of this region. The following is a discussion of these entities, along with their differential diagnosis.

Glomangiopericytoma

Almost from its initial description by Stout and Murray as a tumor primarily composed of pericytic cells [1], hemangiopericytoma (HPC) as a specific tumor type has been debated. The histologic features of the sinonasal type HPC appear unique, combined with a myoid phenotype (a site-specific myofibroma), as a part of the myopericytic family of tumors [2–5]. Although there are morphologic similarities to other myopericytic entities, “GPC” of the sinonasal tract is a relatively distinct tumor, defined as a tumor demonstrating composite features of perivascular modified smooth muscle (myoid phenotype of glomus tumor) arranged in a characteristic syncytium of ovoid to spindle-shaped cells in a variably fibrotic stroma with distinctive branching vessels (HPC) [6–10].

Clinical Features

GPCs predilect to the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, where they comprise <0.5 % of all sinonasal tract neoplasms [6, 11, 12]. With a peak in the 7th decade (range, in utero to 86 years), there is a slight female predominance. This tumor is mostly unilateral, affecting the nasal cavity alone, occasionally extending into the paranasal sinuses, with about 5 % bilateral [6, 11–14]. The majority of patients experience nasal obstruction and epistaxis, with a wide range of other non-specific findings (polyps, sinusitis, headaches, difficulty breathing, congestion), usually present for less than 1 year on average. Severe oncogenic osteomalacia occurring in association with GPC is reported [11, 15]. GPCs are indolent tumors, with an overall excellent survival (>90 % 5-year survival) achieved with complete surgical excision. Recurrences, in up to 40 % of cases, are usually a result of inadequate resection, with the recurrence affecting the same site, occurring from a few months up to two decades after the initial surgery [6, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17]. Aggressive behavior (malignant GPC) is uncommon, suggested by large tumors (>5 cm), bone invasion, profound nuclear pleomorphism, increased mitotic activity (>4/10 high power fields; Ki-67 proliferation index of >10 %), and necrosis, with rare metastasis reported [6, 11–13, 18].

Pathology Findings

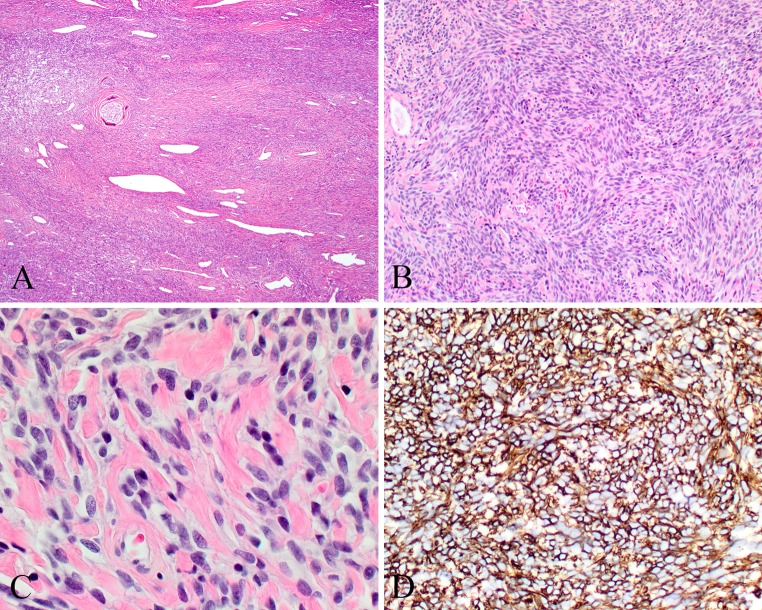

The tumors are generally polypoid, with an average size of 3.0 cm, ranging up to 8.0 cm. They are non-translucent, beefy red to grayish pink, soft, edematous and fleshy to friable tumors. It is remarkable how similar these tumors are one to another. These unencapsulated tumors are identified below an intact respiratory or metaplastic squamous epithelium. Sometimes surface erosion is observed due to friction of a large polypoid mass within the nasal cavity. The characteristic appearance is that of a “patternless” diffuse architecture, frequently effacing or surrounding normal tissue (Fig. 1a). The cells may be arranged in short fascicles, storiform, whorled, “meningothelial”, reticular, or short palisades of closely packed cells. The cells are separated by a rich vascularity, revealing capillaries to large patulous spaces giving the characteristic “staghorn” or “antler-like” configuration. Sometimes focal, there is usually a very prominent thick, acellular peritheliomatous hyalinization, a feature uniquely characteristic of this tumor (Fig. 1a). Lacking distinct cell borders, the closely packed, uniform oval to elongated cells have a syncytial architecture. The nuclei are round, oval to spindle-shaped, vesicular to hyperchromatic, surrounded by non-descript amphophilic, eosinophilic to cleared cytoplasm. Mitoses are limited (<3/10 high power fields) and nuclear pleomorphism is absent to mild. Necrosis and atypical mitoses are not identified. Three additional characteristic findings include mast cells, eosinophils, and extravasated erythrocytes (Fig. 1b), with nearly all tumors possessing these hematologic elements. In a few cases, tumor giant cells may be identified, interpreted to represent aggregation of cells as part of a degenerative change, similar to symplastic glomus tumor [19]. Fibrosis or myxoid change may be present in a few areas, but only in a small percentage of cases. Rare examples of glomangiopericytoma may contain mature adipose tissue (lipomatous GPC) or reveal extramedullary hematopoiesis [6, 20–22]. Concurrent, collision tumors may be found, with SFT noted as a distinctly separate and immunophenotypically different neoplasm [6, 23, 24]. Rarely, severe pleomorphism, necrosis and increased mitoses may be identified, with a malignant designation applied to these cases, which have a much higher chance of developing recurrence or rarely metastasis with death due to disease [6].

Fig. 1.

Glomangiopericytoma (GPC). a Intact surface epithelium overlying a patternless proliferation with well developed peritheliomatous hyalinization. b Oval to elongated nuclei in syncytial cells. Extravasated erythrocytes and eosinophils are noted. c Strong and diffuse smooth muscle actin reaction. d Nuclear β-catenin reaction in the neoplastic cells

Ancillary Techniques

GPC show a distinct immunohistochemistry profile, showing a diffuse reactivity with actins (smooth muscle > muscle specific, Fig. 1c), vimentin, nuclear β-catenin (Fig. 1d), cyclin-D1 and factor XIIIA, while lacking any significant expression of CD34, CD31, FVIII-R Ag, CD117, STAT6, bcl-2, AE1/AE3, CK7, EMA, desmin, S100 protein, GFAP, CD68, CD99, and NSE. Individual cells are highlighted with laminin, similar to argyrophilic stains that envelop individual pericytes by a silver impregnated matrix representing basal laminar material [25]. Rare cases have demonstrated focal bcl-2, S100 protein, CD34, GFAP and CD68 [6, 8, 11, 17, 18, 26]. The intensity of immunoreactivity may vary both within and between cases, ranging from diffuse and strong to focal and weak, but in general, the SMA, β-catenin and cyclin-D1 are strong and diffuse reactions. The tumor giant cells demonstrate an identical immunohistochemical antigenic profile to the tumor cells, representing true neoplastic giant cells not macrophage-type giant cells.

β-catenin, a cadherin-associated membrane protein, participates in the regulation of cell-to-cell adhesion, a terminal component of the Wnt-signaling pathway. Aberrant expression of β-catenin is a well-known event in tumorigenesis and tumor progression [27, 28]. Strong nuclear β-catenin and cyclin D1 immunoexpression is observed in nearly all cases of GPC. Somatic, single nucleotide substitution mutations in CTNNB1 gene encoding β-catenin, specifically in the glycogen serine kinase-3 beta (GSK3β) phosphorylation region (encoded by exon 3) have been identified in GPC (using Sanger sequencing) [7, 8]. These heterozygous mutations involved codons 32, 33, 37, 41 and 45, findings similar to those in other tumor types demonstrated to constitutionally activate β-catenin signaling by upholding cellular β-catenin levels [29]. Accumulation of β-catenin in turn results in nuclear translocation, with the nuclear expression of β-catenin demonstrated to up-regulate cyclin D1, leading to its oncogenic activation. These findings demonstrate that mutation activation of β-catenin with the associated cyclin D1 over expression are central events in the pathogenesis of GPC [8].

Differential Diagnosis

A “hemangiopericytoma-like” pattern can be found in a wide array of neoplasms of divergent differentiation, including lobular capillary hemangioma (LCH), SFT, sinonasal inflammatory polyp, glomus tumor, fibromatosis, JNA, leiomyoma, schwannoma, neurofibroma, meningioma, fibrosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, malignant melanoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, spindled cell “sarcomatoid” squamous cell carcinoma, synovial sarcoma, and mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. A few tumors deserve further elucidation. LCH has a lobular pattern in contrast to the diffuse growth of GPC, with a granulation tissue-like appearance composed of an admixture of inflammatory cells and endothelial-lined vascular spaces. SFT demonstrate a variably cellular proliferation of bland spindle-shaped cells lacking any pattern of growth, with associated “ropey” keloidal collagen bundles and thin-walled vascular spaces. The spindled cells tend to be much more elongated, with tapering elongated nuclei [30–33]. By immunohistochemistry, SFTs reveal diffuse reactivity with CD34, bcl-2, STAT6, and CD99, but are negative with actins and β-catenin [7, 32, 34], although a subset of SFT may express β-catenin [35]. SFT is further characterized by NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion and over expression of the fusion protein [36], a finding not found in GPC [8, 23].

Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Also first described by Stout and Murray in 1942 [1], SFT is now a single entity that combines HPC, giant cell angiofibroma, and SFT [37].

Clinical Features

SFTs are exceedingly rare in the sinonasal tract, even though 10–15 % of SFTs affect the head and neck, usually around the orbit or in the meninges. There is a wide age distribution, although usually found in adults, without a gender predilection. Sinonasal tract SFT patients present with nasal obstruction, epistaxis, or other nonspecific symptoms. Hypoglycemia has been associated with SFT, correlating with expression of insulin growth factors (IGF) by immunohistochemistry. IGF-R mRNA may be identified in tumor cells, even in the absence of clinical hypoglycemia, supporting the notion that IGF-2/IR autocrine loop activation plays an oncogenic role in SFT [38]. Most SFTs in the sinonasal tract are small by virtue of causing symptoms early due to enlargement within a confined space. Therefore, there is an overall good behavior with low local recurrence rate, different from other anatomic sites [39]. Although not reported in the sinonasal tract, SFTs in patients >55 years, with large tumors (>15 cm), with necrosis, increased mitotic activity and/or pleomorphism or incomplete resection are designated as “malignant” or “dedifferentiated” SFT [40, 41], associated with metastasis and disease-specific mortality [42]. Treatment of sinonasal tract SFTs is usually by complete excision or by wide excision. Unresectable or advanced tumors have been treated with chemotherapy (doxorubicin, gemcitabine, or paclitaxel), which is only effective in controlling or stabilizing locally advanced or metastatic disease [43]. Trials of targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors demonstrate that pazopanib may be stabilizing in malignant SFT while regorafenib may be helpful against de-differentiated SFT. Additionally, mTOR inhibitors may become part of treatment for unresectable tumors in the future [44–46].

Pathology Findings

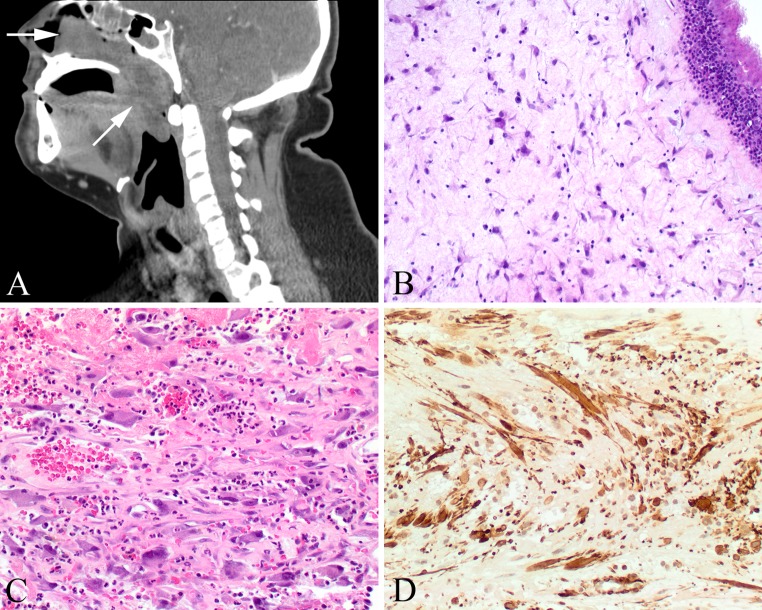

SFT is usually grossly polypoid and firm. By microscopy, SFT is often pseudoencapsulated with compression of adjacent normal tissue. Tumors are variably cellular with hypocellular sclerotic to moderately cellular areas, showing a haphazard arrangement of ovoid to spindles cells (Fig. 2a, b). There is often perivascular and stromal hyalinization, with a keloid-like collagen deposition (Fig. 2c). The vessels are staghorn or hemangiopericytoma-like (Fig. 2a). Histologically worrisome features for more aggressive biologic behavior of SFTs include tumors that have more than 4 mitoses/10 HPFs, tumor necrosis, increased cellularity, pleomorphism, and high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. These more worrisome SFTs often reveal epithelioid round cell features. High grade transformation requires a more bland component of SFT juxtaposed to a frankly demarcated high grade sarcoma component [47].

Fig. 2.

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT). a Patulous and open vessels in a cellular fibrous connective tissue stroma. b Haphazard arrangement of spindled tumor cells. c Keloid-like collagen deposition between spindled cells with ovoid nuclei. d Strong and diffuse cytoplasmic-membrane reaction with CD34

Ancillary Techniques

By immunohistochemistry, SFTs generally show a strong and diffuse reaction with CD34 (Fig. 2d), bcl-2 and CD99, while the tumor cells are non-reactive with desmin, keratins, S100 protein, actins, and nuclear β-catenin [7, 32, 34]. The C-terminus of STAT6 yields a strong nuclear immunoreaction, considered specific and sensitive for SFT [48–50].

At the molecular level, SFTs have been found to have the NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion, which is considered specific to SFT. The NAB2-STAT6 fusion leads to EGR1 activation, transcriptional deregulation of EGR1-dependent target genes, and is a driving event in initiation of SFT. By quantitative real-time PCR, there are high expression levels of the 5′-end of NAB2 and the 3′-end of STAT6, which corresponded to NAB2/STAT6 fusion, while tissue microarrays revealed differentially expressed GRIA2 regulating gene at the protein level [51]. Further, by tissue microarray, Demicco et al. have identified angiogenic and growth factor signaling pathway alterations in SFT with immunohistochemical staining for PDGFα and β, IGF1R, EGFR, MET, and VEGF. They identified over expression of multiple growth factors in these tumors, correlating with activation of the AKT pathway. As expected, more cellular tumors were associated with high vascular endothelial growth factor and PDGFβ, whereas metastatic tumors more frequently over expressed PDGFRα compared to localized tumors [52]. 13q and 17p deletions and p53 mutations (over expression), in combination with TERT promoter mutations seem to play a role in the high grade transformation of SFT [53, 54].

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for sinonasal tract SFT include glomangiopericytoma, fibrous histiocytoma, angioleiomyoma (vascular leiomyoma), schwannoma, synovial sarcoma, and mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. In general, the patterns of growth, cellular features, lack of CD34 and STAT6 expression by immunohistochemistry, and lack of specific molecular changes in the tumors in the differential diagnosis versus SFT, allow for appropriate separation.

Antrochoanal Polyp

Antrochoanal polyp (ACP) was first described by Gustav Killian in 1906 as a clinically distinctive variant of sinonasal inflammatory polyp (SNIP) that originates from the maxillary sinus and extends through an ostium, across the choana, and often into the nasopharynx or oropharynx (Fig. 3a) [55, 56]. Originally thought to be increased in patients who have allergies, there is little well documented evidence for such [57]. Repeated bouts of sinusitis seem to be associated with polyp development, whether caused by allergy, vasomotor rhinitis, infections, cystic fibrosis, aspirin intolerance, or even nickel exposure. There is significantly higher expression of basic fibroblast growth factor and transforming growth factor-β in ACP than in tissue removed from patients with chronic rhinosinusitis [58]. In addition, ACP demonstrates higher levels of mucin gene expression than chronic rhinosinusitis, including MUC5AC, MUC5B, and MUC8, supporting the notion of a distinct clinicopathological entity. Fluid accumulates in the lamina propria, which, along with inflammatory factors and overproduction of tissue-derived growth factors, results in polyp formation. Specifically, ACPs may be associated with mucocele or antral cyst formation in the maxillary sinus due to increased pressure in the antrum (Highmore), with pressure resulting in expansion and herniation or prolapse through an accessory or secondary ostium below the middle meatus [55, 56]. These polyps frequently cross the choana (boundary between the nasal cavity and nasopharynx). Rare reports in siblings may suggest an inherited or familial etiology [59].

Fig. 3.

Antrochoanal polyp (ACP). a A large polyp (arrows) begins in the maxillary sinus and extends into the nasopharynx. b Intact respiratory epithelium with submucosal stellate fibroblasts. c The atypical fibroblastic cells are often identified around areas of vascular injury, associated with hemorrhage. d The fibroblasts show a strong and diffuse reaction with smooth muscle actin

Clinical Features

SNIPs are relatively common, but only about 3–6 % of all SNIPs are ACP [56]. Up to 20 % of children with cystic fibrosis have polyps, but these do not usually fit into the ACP category. There is a male to female predilection for ACPs (2:1), while there is no gender predilection for SNIPs. ACPs tend to develop in younger patients than classical SNIPs, affecting teenagers and young adults (mean 24–28 years) [55, 60]. Symptoms are non-specific, most commonly including nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea [55, 60–63]. Patients tend to have a longer duration of symptoms with ACPs than with SNIPs [63]. While the vast majority of ACPs are unilateral, synchronous bilateral involvement may be observed, along with bilateral maxillary sinusitis [61]. It is not uncommon to have concurrent SNIPs, allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis and/or turbinate hypertrophy. Depending on size, there may be posterior extension of the polyp, resulting in possible obstruction, raising the clinical suspicion of a primary nasopharyngeal lesion (such as JNA). As such, ACPs may be examined through the open mouth as a mass in the oro- or nasopharynx. The clinical diagnosis is usually augmented by rhinoscopy, nasal endoscopy and/or computed tomography (CT) studies. By imaging, ACPs tend to be a single, unilateral expansile process, revealing nearly total maxillary sinus opacification, mucosal thickening, and mucus retention. The stalk of attachment within the medial wall is not usually identified by imaging, but a large, pedunculated polyp will expand into and fill the nasal cavity and/or pharynx [55, 62, 64, 65]. Uncommonly, choanal polyps will arise from the sphenoid or ethmoid sinus, referred to as sphenochoanal or ethmochoanal polyps, revealing a stalk of attachment in the named sinus [61]. Conservative combination endoscopic (Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: FESS) and open surgery (mini-Caldwell procedure) to include the stalk and sinus contents, seems to yield the lowest risk of recurrence [55, 60, 64], especially if the point of attachment cannot be identified.

Pathology Findings

ACPs tend to be firmer and non-translucent compared to SNIPs, with a distinct stalk. Histologically, ACPs lack minor mucoserous glands and a well-developed eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 3b). Goblet cells within the surface epithelium are less frequent in ACPs than in usual SNIPs, and surface squamous metaplasia is observed in ACPs but not as often in SNIPs [57, 63]. The surface epithelium basement membrane is inconspicuous in most ACPs, whereas SNIPs, especially those associated with allergy, reveal a remarkably thickened basement membrane. Chronic inflammation is identified to a much greater degree when the ACPs extend into the nasopharynx than when confined to the nasal cavity [65]. It is not uncommon for these polyps to undergo secondary change, which results from either chronic or subacute vascular compromise (i.e., stalk torsion). This results in partial degeneration and destruction of the endothelial cells. Cystic degeneration of the stroma is frequently observed, creating a loosely reticular pattern or “pseudoangiomatous” growth [63]. It is not uncommon to see partial to complete infarction, secondary fibrosis, minimal to extensive hemorrhage, and even organizing thrombus or papillary endothelial hyperplasia (Masson endothelial hyperplasia). These secondary changes or injuries will frequently be associated with dispersed, single atypical stromal cells. These cells are a component of wound healing and are myofibroblastic in origin. These cells can appear quite bizarre, with enlarged pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei and sometimes remarkably prominent nucleoli (Fig. 3c). The cytoplasm ranges from eosinophilic to slightly basophilic, with a stellate to bipolar appearance, with “strap-like” pseudopodal extensions. These cells are often clustered adjacent to areas of injury or surface erosion, including around any thrombosed vasculature or acute infarction. However, these cells are almost never mitotically active.

Ancillary Techniques

The atypical stromal myofibroblasts are positive with vimentin and actins (Fig. 3d) with occasional expression of cytokeratin. However, there is no reaction with desmin, myoglobin, myogenin, MYOD1, or with S100 protein. Vascular markers will highlight the vessels, but the atypical stromal cells are non-reactive.

Differential Diagnosis

One of the most important differential diagnostic considerations is rhabdomyosarcoma. The atypical myofibroblastic stromal cells may give the appearance of rhabdomyoblasts. Overall, rhabdomyosarcoma tends to be more cellular than ACP, often with a “cambium layer” gradient of high to low cellularity. Further, rhabdomyosarcoma is likely to involve a wider area of the stroma, with the neoplastic cells noted throughout the tissue, not just adjacent to areas of injury. Rhabdomyoblasts are more pleomorphic, have a higher nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, and may even declare cross striations. Mitoses are increased and necrosis may be present. Negative desmin and myoregulatory proteins MyoD1 and myf4 (skeletal muscle specific myogenin) clearly separate these polyps from rhabdomyosarcoma. Chronic rhinosinusitis lacks a polypoid architecture, but when fragmented, the presence of stromal edema, mild chronic inflammation, and thickened basement membranes helps to separate it from ACPs. JNAs arise in the nasopharynx, with a combination of variably sized vessels and collagen deposition often with stellate stromal cells.

Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) was first described by Hippocrates in the fifth century BC, but Friedberg first used the term angiofibroma in 1940. This tumor specifically arises from erectile-like fibrovascular stroma in the posterolateral wall of the roof of the nose and nasopharynx.

Clinical Features

These relatively uncommon tumors, comprising less than 1 % of nasopharyngeal tumors, are found almost exclusively in adolescent males (10–25 years); in Caucasian patients, these boys are often fair-skinned and red-haired. Occasional cases are identified in older patients; if identified in females, chromosomal evaluation reveals testicular feminization. These tumors show a puberty-associated growth, correlating to a strong expression of tumor cell androgen receptors. The classical triad of epistaxis, unilateral nasal obstruction and a mass may be accompanied by nasal discharge, proptosis, diplopia, headache, and pain. Tumors often expand into adjacent structures, including the orbit or cranial cavity. JNAs may spontaneously regress after puberty. The overall behavior for JNAs is benign, but these tumors have high vascularity and bleed severely on manipulation and biopsy. If incompletely removed, local recurrence may develop in up to 40 % of cases, usually within the first year. Treatment includes preoperative embolization, although the tumors are often difficult to excise. Chemo- or radiation therapy may be employed for incompletely excised or locally aggressive disease. Rarely are sarcomatous or squamous cell carcinoma transformation after radiation therapy reported [66].

Pathology Findings

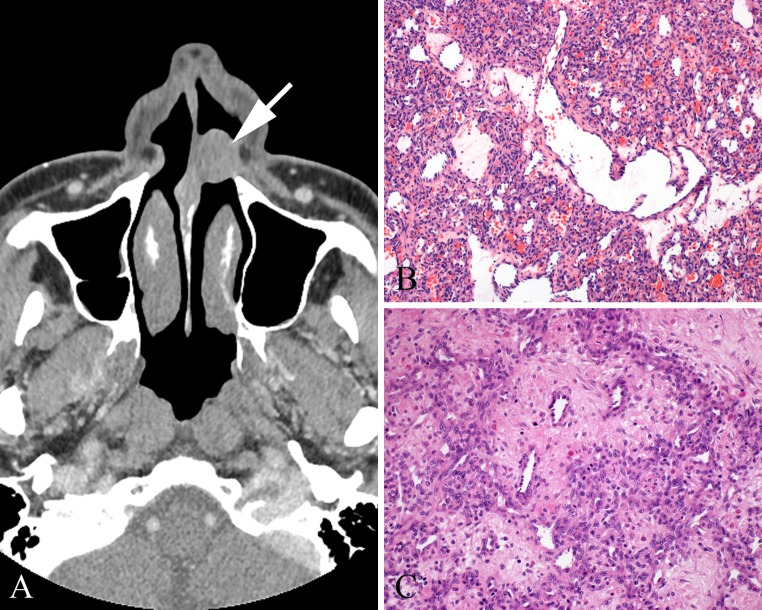

Grossly, these are well circumscribed, unencapsulated polypoid fibrous masses with a spongy to solid tan-grey cut surface (Fig. 4a). They can reach large sizes, up to 22 cm, but generally are a mean of 4 cm. A composite of radiographic, clinical and pathology staging is based on tumor limited to the nasopharynx without bone destruction (stage I) to massive invasion of the cranial cavity, cavernous sinuses, optic chiasm, or pituitary fossa (stage IV). By microscopy, there is an intricate mixture of stellate and staghorn blood vessels with variable vessel wall thickness ranging from capillaries with a single layer of endothelium to large thick-walled, smooth-muscle lined vessels, to patulous vessels lacking any muscle wall (Fig. 4b–d). The irregular fibrous stroma is loose and edematous or can be densely sclerotic and acellular. The stromal cells are stellate fibroblasts that may demonstrate small pyknotic to large vesicular nuclei. Larger vessels are found at the base of the lesion, ramifying to smaller vessels with plump endothelium at the growing edge of the tumor. However, haphazard vascular distribution is seen. Multinucleated stromal cells are common. Mitoses are rare to absent. Minimal lymphocytic inflammation may be present, but scattered mast cells are frequent.

Fig. 4.

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA). a Grossly, a large, fibrous polypoid mass often takes the shape of the nasal cavity. b Variable size and type of vessels in a collagenized stroma. c Smooth muscle walled vessels and large patulous vessels within intervening erectile tissue type collagenized stroma. d Thick, muscled-walled vessels, along with several other vessel types comprise a JNA

Ancillary Techniques

By immunohistochemistry, CD31, CD34 and SMA highlight vessels; the stromal cells are negative for CD34, S100 protein, desmin, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpes virus-8 and keratin [67]. c-KIT (CD117) is positive and androgen receptor is found in up to 75 % of cases.

Gene expression reveals chromosomal imbalances in both stroma and endothelium with AURKB, FGF18, and SUPT16H identified as potential therapeutic molecular targets [68]. Another study identified that GSTM1 (null genotype) is linked to the development of JNA [69]. SYK protein kinase (tyrosine kinase) is differentially expression in low and high stage JNA, suggesting a possible molecular treatment target, along with angiogenic protein basic fibroblast growth factor [70, 71].

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes sinonasal inflammatory polyps, hemangiomas (lobular capillary hemangioma specifically), antrochoanal polyp, and SFT. In general, SNIPs have mucoserous glands, less fibrous stroma, and lack significant erectile-tissue vasculature. LCHs usually have a rich inflammatory component and a more ramifying vascular pattern, while arising from a different anatomic site. Antrochoanal polyps show heavy stromal fibrosis, but lack the vascular pattern of a JNA and arises from a different anatomic site (maxillary sinus). SFTs demonstrate a much greater cellularity, show more collagen deposition, do not show the diversity of vascularity of a JNA, and are strongly positive with CD34 and STAT6 by immunohistochemistry.

Lobular Capillary Hemangioma

Lobular capillary hemangioma (LCH) was first described as pyogenic granuloma in 1897 by two French surgeons, Poncet and Dor, who named this lesion botryomycosis hominis. Synonyms include pyogenic granuloma; capillary hemangioma, and epulis gravidarum. Mucosal hemangiomas of the sinonasal tract account for 10 % of all head and neck hemangiomas, with LCHs the most common. Capillary hemangiomas are derived from capillary sized vessels that are too many per unit space, yet retain their normal architecture in a trunk and branch distribution, with pericytes around the vessels. The consideration that LCH is reactive is due to its association with injury and hormonal factors including pregnancy and oral contraceptive use.

Clinical Features

Sinonasal capillary hemangiomas occur in all ages, although there is a peak in children and adolescent males, females in the reproductive years, and then an equal sex distribution beyond 40 years of age, whereas cavernous hemangiomas tend to arise in men in the 5th decade. Patients present with unilateral epistaxis (75 %) and/or an obstructive painless mass (35 %) of short duration, while sinusitis, proptosis, mass, anesthesia or pain are uncommon. Tumors affect the septum (particularly the anterior septum [Little’s area]; Fig. 5a) most often, followed by the tip of the turbinate and paranasal sinuses. Surgical treatment is required to decrease the potential for associated aplasia of the nasal cartilage and disfigurement. Preoperative embolization decreases bleeding. On the other hand, regression will occur in pregnancy-associated tumors after parturition. Multiple recurrences are more common in children if the lesional bed is not completely removed [72].

Fig. 5.

Lobular capillary hemangioma (LCA). a A septal mass (Little area, arrow) is a characteristic location. b Large central vessel with small ramifying capillaries. This lesion appears cellular because of proliferation of pericytes surrounding proliferated endothelial cells of capillaries; normal form mitotic activity may be abundant. c Lobular arrangement of vessels around a central penetrating vessel

Pathology Findings

LCHs range up to 5 cm, with a mean size <1.5 cm. The tumors are red to blue, submucosal, soft, compressible, flat or polypoid lesions, often with an ulcerated surface. By microscopy, LCHs have a lobular, trunk-and-branch like organized pattern of capillary proliferation, surrounded by pericytes (Fig. 5b). Mitoses are highly variable because capillaries and pericytes can have brisk normal form mitoses. The lobules are separated by a fibromyxoid stroma (Fig. 5c) and the cellularity of the lobules may be quite high. An inflammatory infiltrate is invariably present, more so when ulcerated.

Ancillary Techniques

LCHs are diagnosed by H&E stained material, yet the endothelial cells are CD31, CD34, Factor VIIIR-Ag, and FLI1 positive while the pericytes are positive for SMA; CD31 is considered the most reliable endothelial marker. Glut-1 is positive in infantile hemangioma, but not in LCH. VEGF is highest in LCHs among benign vascular tumors [73], and is associated with apoptosis of endothelial cells and regression of pregnancy induced LCHs [74].

Differential Diagnosis

Sinonasal tract LCHs are distinguished from granulation tissue, SNIPs, JNAs, and angiosarcomas. Most importantly, LCHs are an intravascular benign process that does not have intervening stroma seen in JNA and is not an extravascular extension of malignant endothelial cells, leaving their normal pericytic confines and losing SMA, as observed in angiosarcoma [75].

Meningioma

Meningiomas constitute between 20 and 36 % of intracranial neoplasms [76, 77], but primary extracranial (ectopic, extracalvarial) meningiomas account for only about 2 % of all meningiomas, with meningiomas of the sinonasal tract comprising <0.1 % of non-epithelial neoplasms [78–80]. Extracranial direct extension into the sinonasal tract of meningiomas is much more likely than a primary, ectopic tumor, and thus, by current consensus, a primary diagnosis should not be rendered when there is a detectable intracranial mass or “dural enhancement” by imaging [79–81].

Meningiomas are derived from arachnoid cap cells (arachnoid granulations, pacchionian bodies), located extra-cranially within the sheaths of nerves or vessels as they emerge through the skull foramina or suture lines of the skull, presenting in “ectopic” sinonasal tract locations. While radiation exposure and sex hormones are known to play a role in meningioma development [76, 78, 80], these factors are unproven in sinonasal tract tumors. There are three grades (as defined by the World Health Organization) and 15 recognized histologic types [76].

Clinical Features

There is a female predilection (1.7–2.1:1), with patients commonly presenting in the 5th decade (mean 44 years; range 9–88 years), similar to intracranial lesions. Men tend to be younger than women by a decade and also tend to develop atypical and anaplastic meningiomas more often than women [76, 77]. Because symptoms are non-specific, such as polyps or nasal obstruction, they are present for a long duration (mean 4 years) [78–80]. Whereas meningiomas are well described in neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), this association is not significant in sinonasal tract tumors.

Sinonasal tract meningiomas involve both the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses more frequently than either location alone, although each sinus may be individually affected. A majority are left-sided [78–80]. The imaging findings within the sinonasal tract are non-specific, with sinus or nasal cavity opacification, perhaps with bone erosion, sclerosis or hyperostosis. CT studies may identify a destructive mass, revealing the marked tendency to permeation of the crevices, suture lines, foramina and cranial nerve spaces of the skull, but sometimes a small dural or en plaque meningioma may be distinctly challenging to recognize radiographically [80, 81].

Complete extirpation is difficult to achieve due to the complex anatomic restrictions. In general, however, the prognosis of primary meningioma of the sinonasal tract appears to be excellent without any other therapy. Radiation is employed for residual or incompletely excised tumors, while sunitinib malate (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) has been demonstrated to be active [82]. Recurrences develop (about 30 % of cases) due to incompletely excised tumors, but metastasis or malignant transformation is not reported in the sinonasal tract [78, 80]. In contrast to intracranial tumors, gender and age do not influence prognosis. It is noteworthy that features associated with an increased rate of recurrence in CNS meningiomas (increased mitotic activity, loss of architectural pattern, hypervascularity, necrosis, spindle cell formation, nuclear pleomorphism) [77, 83–85] are rarely found in sinonasal tract tumors, and when present, are not associated with a worse outcome. If there is death with tumor, it is usually due to involvement of the vital structures of the mid-facial region or to complications of the surgery, rather than to the aggressive nature of the tumor.

Pathology Findings

The tumors range in size up to 8.0 cm, with a mean size of 3 cm. Macroscopically, the tumors are often polypoid, covered by an intact surface epithelium, frequently expanding into bone. Calcifications may be visible.

Sinonasal tract meningiomas exhibit the same variety of histological patterns as their intracranial counterparts, although meningothelial meningiomas are the most common. The meningocytes may mingle with the surface epithelium, suggesting squamous differentiation or origin (Fig. 6a). The tumors are composed of lobules of cells, with a meningothelial whorling with isolated psammomatous calcifications (Fig. 6b, c). The cells appear as a syncytium with indistinct borders, bland nuclei, delicate chromatin, small nucleoli, and occasional intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 6c) [76, 80]. Specific types, such as transitional (spindle cell component), metaplastic (lipidized cells within the tumor), and psammomatous types (abundant, confluent psammoma bodies) are occasionally identified [76, 80]. A combination of increased mitotic activity (4–19/10 HPF) with three or more of the following features is diagnosed as atypical meningioma: loss of architectural pattern (sheet-like), hypercellularity, small cells with high nucleus: cytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli, and geographic necrosis; [76, 83, 85] anaplasia, ≥20 mitoses/10 HPFs and the papillary or rhabdoid cell types are referred to as anaplastic (Grade III) tumors.

Fig. 6.

Meningioma. a The neoplasm is noted invading between the minor mucoserous glands. b A lobule of tumor cells below an intact respiratory epithelium. c Meningothelial pattern of growth, with whorls. Intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions are noted. Psammoma bodies are present. d Strong, but focal EMA immunoreactivity is observed

Ancillary Techniques

Meningiomas typically react with epithelial membrane antigen (EMA, often weakly and focally; Fig. 6d), CK18 and vimentin. Rare tumors may react with pancytokeratin or other keratins, CD34 (fibrous and atypical types), and S-100 protein (fibrous type), while glial fibrillary acidic protein and smooth muscle actin are non-reactive, except in rhabdoid and whorling-sclerosing variants [77]. STAT6 is negative, helping to separate fibrous meningioma from SFT [86]. Ki-67 is positive to a variable degree and intensity in all cases, although usually low [76, 80].

A number of genetic and molecular pathways are disrupted in meningioma, contributing to its tumorigenesis, with complex karyotypes and involvement of multiple signaling pathways. Abnormalities in genes on chromosomes 1p, 6, 9p, 10q, 14q, 17p, 18q and 22 have been described, [77, 84, 87, 88] with deletions of chromosome 22 (monosomy 22) the most consistent cytogenetic alteration. Specifically, these include mutations of the NF2 gene (chromosome 22q12.2), which codes for the protein merlin, a tumor suppressor gene. Merlin is lost in different meningioma types, while Yes-associated protein (YAP) is increased, resulting in meningioma proliferation [89]. Loss of 1p is the second most common chromosomal abnormality, correlated to ELAVL4 gene which reveals a distinct gender difference [90], and to ALPL (1p36.1-p34) which is down regulated, associated with high grade tumors and recurrence [88]. Several other genes and chromosomes have been elucidated in meningioma, but tend to be associated with Grade II and III tumors or with tumor progression, features not normally present in the sinonasal tract [77, 84, 87, 91].

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of sinonasal tract meningioma includes squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, SFT, GPC, paraganglioma, schwannoma, chordoma and aggressive psammomatoid ossifying fibroma [6, 36, 77, 79, 80, 86, 92, 93]. The general histologic features and immunohistochemical findings can usually separate between these tumors. Carcinomas will tend to reveal more pleomorphism, may reveal keratinization, have an increased mitotic index, and will be positive with a variety of cytokeratins, including CK5/6, along with strongly reactive p63 and p40. Melanomas may grow in a meningothelial pattern, but S100 protein, SOX10, HMB45, Melan-A, and tyrosinase are not usually positive in meningiomas, although fibrous meningiomas are S100 protein positive. SFTs may be included in the differential for fibrous meningiomas, where ~40 % of fibrous meningiomas and 60 % of atypical meningiomas are positive with CD34, but STAT6 is strongly positive in SFT and not in meningioma, while claudin-1 is positive in many meningiomas, but not in SFT. GPCs reveal a syncytial growth, a rich vascular pattern, peritheliomatous hyalinization, and an inflammatory infiltrate, with actins and nuclear β-catenin reactivity. Paragangliomas have a nested or zellballen arrangement, with neuroendocrine markers and a supporting sustentacular S100 protein reaction. Schwannomas have hyper- and hypocellular areas, palisaded nuclei, and perivascular hyalinization, with a strong S100 protein and SOX10 reaction, but negative claudin-1 reaction. Chordoma and chordoid meningioma may look similar, but brachyury is positive only in chordoma. An aggressive psammomatoid ossifying fibroma may be confused with meningioma as both lesions may have psammoma bodies, but meningiomas lack associated osteoclasts and osteoblasts and does not contain the storiform and more compact stromal matrix.

In summary, familiarity with the specific and unique soft tissue tumors of the sinonasal tract and recognition of common soft tissue tumors and meningiomas as they may affect the sinonasal tract, should allow for correct interpretation, utilizing pertinent and selected ancillary studies to confirm the diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or Johns Hopkins Medical Institution.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

There are no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Stout AP, Murray MR. Hemangiopericytoma. A vascular tumor featuring Zimmerman’s pericytes. Ann Surg. 1942;116:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194207000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, et al. Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer. 2002;94:1057–1068. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suster S, Nascimento AG, Miettinen M, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of soft tissue. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1257–1266. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ. Cell-type- and tumour-type-related patterns of bcl-2 reactivity in mesenchymal cells and soft tissue tumours. Virchows Arch. 1998;433:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s004280050244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miettinen M, Paal E, Lasota J, et al. Gastrointestinal glomus tumors: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 32 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:301–311. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson LD, Miettinen M, Wenig BM. Sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 104 cases showing perivascular myoid differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:737–749. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haller F, Bieg M, Moskalev EA, et al. Recurrent mutations within the amino-terminal region of beta-catenin are probable key molecular driver events in sinonasal hemangiopericytoma. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:563–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lasota J, Felisiak-Golabek A, Aly FZ, et al. Nuclear expression and gain-of-function beta-catenin mutation in glomangiopericytoma (sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma): insight into pathogenesis and a diagnostic marker. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:715–720. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fletcher CD. Hemangiopericytoma–a dying breed? Reappraisal of an “entity” and its variant. A hypothesis. Curr Diagn Pathol. 1994;1:19–23. doi: 10.1016/S0968-6053(06)80005-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granter SR, Badizadegan K, Fletcher CD. Myofibromatosis in adults, glomangiopericytoma, and myopericytoma: a spectrum of tumors showing perivascular myoid differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:513–525. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199805000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catalano PJ, Brandwein M, Shah DK, et al. Sinonasal hemangiopericytomas: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of seven cases. Head Neck. 1996;18:42–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199601/02)18:1<42::AID-HED6>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Compagno J, Hyams VJ. Hemangiopericytoma-like intranasal tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 23 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;66:672–683. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/66.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billings KR, Fu YS, Calcaterra TC, et al. Hemangiopericytoma of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol. 2000;21:238–243. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2000.8378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.el Naggar AK, Batsakis JG, Garcia GM, et al. Sinonasal hemangiopericytomas. A clinicopathologic and DNA content study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:134–137. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880020026010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandwein-Gensler M, Siegal GP. Striking pathology gold: a singular experience with daily reverberations: sinonasal hemangiopericytoma (glomangiopericytoma) and oncogenic osteomalacia. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:64–74. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marianowski R, Wassef M, Herman P, et al. Nasal haemangiopericytoma: report of two cases with literature review. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:199–206. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100143580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eichhorn JH, Dickersin GR, Bhan AK, et al. Sinonasal hemangiopericytoma. A reassessment with electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:856–866. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kowalski PJ, Paulino AF. Proliferation index as a prognostic marker in hemangiopericytoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2001;23:492–496. doi: 10.1002/hed.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enzinger FM, Smith BH. Hemangiopericytoma. An analysis of 106 cases. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:61–82. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(76)80006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folpe AL, Devaney K, Weiss SW. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a rare variant of hemangiopericytoma that may be confused with liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1201–1207. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199910000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen GP, Dickersin GR, Provenzal JM, et al. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma. A histologic, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a unique variant of hemangiopericytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:748–756. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guillou L, Gebhard S, Coindre JM. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a fat-containing variant of solitary fibrous tumor? Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural analysis of a series in favor of a unifying concept. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1108–1115. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agaimy A, Barthelmeß S, Boltze C, et al. Phenotypical and molecular distinctness of sinonasal haemangiopericytoma compared to solitary fibrous tumour of the sinonasal tract. Histopathology. 2014;65:667–673. doi: 10.1111/his.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gengler C, Guillou L. Solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma: evolution of a concept. Histopathology. 2006;48:63–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nappi O, Ritter JH, Pettinato G, et al. Hemangiopericytoma: histopathological pattern or clinicopathologic entity? Semin Diagn Pathol. 1995;12:221–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter PL, Bigler SA, McNutt M, et al. The immunophenotype of hemangiopericytomas and glomus tumors, with special reference to muscle protein expression: an immunohistochemical study and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 1991;4:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005;434:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nature03319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:387–398. doi: 10.1038/nrc2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huss S, Nehles J, Binot E. β-catenin (CTNNB1) mutations and clinicopathological features of mesenteric desmoid-type fibromatosis. Histopathology. 2013;62:294–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukunaga M, Ushigome S, Nomura K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the nasal cavity and orbit. Pathol Int. 1995;45:952–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1995.tb03421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witkin GB, Rosai J. Solitary fibrous tumor of the upper respiratory tract. A report of six cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:842–848. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zukerberg LR, Rosenberg AE, Randolph G, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:126–130. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199102000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kempson RL, Fletcher CDM, Evans HL, et al. Fibrous and myofibroblastic tumors. In: Kempson RL, Fletcher CDM, Evans HL, Hendrickson MR, Sibley RK, et al., editors. Atlas of tumor pathology: tumors of the soft tissues. Bethesda: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2001. pp. 23–112. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox DP, Daniels T, Jordan RC. Solitary fibrous tumor of the head and neck. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rakheja D, Molberg KH, Roberts CA. Immunohistochemical expression of beta-catenin in solitary fibrous tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:776–779. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-776-IEOCIS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chmielecki J, Crago AM, Rosenberg M. Whole exome sequencing identifies a recurrent NAB2-STAT6 fusion in solitary fibrous tumors. Nat Genet. 2013;45:131–132. doi: 10.1038/ng.2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furusato E, Valenzuela IA, Fanburg-Smith JC, et al. Orbital solitary fibrous tumor: encompassing terminology for hemangiopericytoma, giant cell angiofibroma, and fibrous histiocytoma of the orbit: reappraisal of 41 cases. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z, Wang J, Zhu Q, et al. Huge solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura with hypoglycemia and hypokalemia: a case report. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;20:165–168. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.12.01913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldi GG, Stacchiotti S, Mauro V, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of all sites: outcome of late recurrences in 14 patients. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2013;3:4. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xue Y, Chai G, Xiao F, et al. Post-operative radiotherapy for the treatment of malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the nasal and paranasal area. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:926–931. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunzel J, Hainz M, Ziebart T, et al. Head and neck solitary fibrous tumors: a rare and challenging entity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3670-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demicco EG, Park MS, Araujo DM, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor: a clinicopathological study of 110 cases and proposed risk assessment model. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1298–1306. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park MS, Ravi V, Conley A, et al. The role of chemotherapy in advanced solitary fibrous tumors: a retrospective analysis. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2013;3:7. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stacchiotti S, Tortoreto M, Baldi GG, et al. Preclinical and clinical evidence of activity of pazopanib in solitary fibrous tumour. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3021–3028. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tazzari M, Negri T, Rini F, et al. Adaptive immune contexture at the tumour site and downmodulation of circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the response of solitary fibrous tumour patients to anti-angiogenic therapy. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1350–1362. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamada Y, Kohashi K, Fushimi F, et al. Activation of the Akt-mTOR pathway and receptor tyrosine kinase in patients with solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer. 2014;120:864–876. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosquera JM, Fletcher CD. Expanding the spectrum of malignant progression in solitary fibrous tumors: a study of 8 cases with a discrete anaplastic component–is this dedifferentiated SFT? Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1314–1321. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a6cd33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doyle LA, Vivero M, Fletcher CD, et al. Nuclear expression of STAT6 distinguishes solitary fibrous tumor from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:390–395. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshida A, Tsuta K, Ohno M, et al. STAT6 immunohistochemistry is helpful in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:552–559. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Demicco EG, Harms PW, Patel RM, et al. Extensive survey of STAT6 expression in a large series of mesenchymal tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143:672–682. doi: 10.1309/AJCPN25NJTOUNPNF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohajeri A, Tayebwa J, Collin A, et al. Comprehensive genetic analysis identifies a pathognomonic NAB2/STAT6 fusion gene, nonrandom secondary genomic imbalances, and a characteristic gene expression profile in solitary fibrous tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:873–886. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Demicco EG, Wani K, Fox PS, et al. Histologic variability in solitary fibrous tumors reflects angiogenic and growth factor signaling pathway alterations. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akaike K, Kurisaki-Arakawa A, Hara K, et al. Distinct clinicopathological features of NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene variants in solitary fibrous tumor with emphasis on the acquisition of highly malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dagrada GP, Spagnuolo RD, Mauro V, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors: loss of chimeric protein expression and genomic instability mark dedifferentiation. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:1074–1083. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balikci HH, Ozkul MH, Uvacin O, et al. Antrochoanal polyposis: analysis of 34 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:1651–1654. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frosini P, Picarella G, De CE. Antrochoanal polyp: analysis of 200 cases. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2009;29:21–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ozcan C, Zeren H, Talas DU, et al. Antrochoanal polyp: a transmission electron and light microscopic study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:55–60. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahfouz ME, Elsheikh MN, Ghoname NF. Molecular profile of the antrochoanal polyp: up-regulation of basic fibroblast growth factor and transforming growth factor beta in maxillary sinus mucosa. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:466–470. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2006.20.2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montague ML, McGarry GW. Familial antrochoanal polyposis–a case report. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:507–508. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nikakhlagh S, Rahim F, Saki N, et al. Antrochoanal polyps: report of 94 cases and review the literature. Niger J Med. 2012;21:156–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aydin O, Keskin G, Ustundag E, et al. Choanal polyps: an evaluation of 53 cases. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21:164–168. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarafraz M, Niazi A, Araghi S. The prevalence of clinical presentations and pathological characteristics of antrochoanal polyp. Niger J Med. 2015;24:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skladzien J, Litwin JA, Nowogrodzka-Zagorska M, et al. Morphological and clinical characteristics of antrochoanal polyps: comparison with chronic inflammation-associated polyps of the maxillary sinus. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2001;28:137–141. doi: 10.1016/S0385-8146(00)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Atighechi S, Baradaranfar MH, Karimi G, et al. Antrochoanal polyp: a comparative study of endoscopic endonasal surgery alone and endoscopic endonasal plus mini-Caldwell technique. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:1245–1248. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0890-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chung SK, Chang BC, Dhong HJ. Surgical, radiologic, and histologic findings of the antrochoanal polyp. Am J Rhinol. 2002;16:71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mallick S, Benson R, Bhasker S, et al. Long-term treatment outcomes of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma treated with radiotherapy. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2015;35:75–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carlos R, Thompson LD, Netto AC, et al. Epstein-Barr virus and human herpes virus-8 are not associated with juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2:145–149. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0069-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Silveira SM, Custodio Domingues MA, Butugan O, et al. Tumor microenvironmental genomic alterations in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Head Neck. 2012;34:485–492. doi: 10.1002/hed.21767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maniglia MP, Ribeiro ME, Costa NM, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma in brazilian patients. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;30:616–622. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2013.806620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Renkonen S, Kankainen M, Hagstrom J, et al. Systems-level analysis of clinically different phenotypes of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:2728–2735. doi: 10.1002/lary.23592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schiff M, Gonzalez AM, Ong M, et al. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma contain an angiogenic growth factor: basic FGF. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:940–945. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith SC, Patel RM, Lucas DR, et al. Sinonasal lobular capillary hemangioma: a clinicopathologic study of 34 cases characterizing potential for local recurrence. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:129–134. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0409-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dyduch G, Okon K, Mierzynski W. Benign vascular proliferations–an immunohistochemical and comparative study. Pol J Pathol. 2004;55:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yuan K, Lin MT. The roles of vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin-2 in the regression of pregnancy pyogenic granuloma. Oral Dis. 2004;10:179–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1601-0825.2003.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nelson BL, Thompson LD. Sinonasal tract angiosarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 10 cases with a review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12105-007-0017-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. World health organization classification of tumours of the central nervous system. 4. Lyon: IARC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shibuya M. Pathology and molecular genetics of meningioma: recent advances. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2015;55:14–27. doi: 10.2176/nmc.ra.2014-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perzin KH, Pushparaj N. Nonepithelial tumors of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and nasopharynx. A clinicopathologic study. XIII: Meningiomas. Cancer. 1984;54:1860–1869. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841101)54:9<1860::AID-CNCR2820540916>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rushing EJ, Bouffard JP, McCall S, et al. Primary extracranial meningiomas: an analysis of 146 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:116–130. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0118-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thompson LD, Gyure KA. Extracranial sinonasal tract meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:640–650. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moulin G, Coatrieux A, Gillot JC, et al. Plaque-like meningioma involving the temporal bone, sinonasal cavities and both parapharyngeal spaces: CT and MRI. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:629–631. doi: 10.1007/BF00600427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kaley TJ, Wen P, Schiff D, et al. Phase II trial of sunitinib for recurrent and progressive atypical and anaplastic meningioma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:116–121. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Perry A, Stafford SL, Scheithauer BW, et al. Meningioma grading. An analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1455–1465. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199712000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Linsler S, Kraemer D, Driess C, et al. Molecular biological determinations of meningioma progression and recurrence. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Perry A, Scheithauer BW, Stafford SL, et al. “Malignancy” in meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients, with grading implications. Cancer. 1999;85:2046–2056. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990501)85:9<2046::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schweizer L, Koelsche C, Sahm F, et al. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma and solitary fibrous tumors carry the NAB2-STAT6 fusion and can be diagnosed by nuclear expression of STAT6 protein. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:651–658. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miller R, DeCandio ML, Xon-Mah Y, et al. Molecular targets and treatment of meningioma. J Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;1:10001011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Domingues P, Gonzalez-Tablas M, Otero A, et al. Genetic/molecular alterations of meningiomas and the signaling pathways targeted. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10671–10688. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gusella JF, Ramesh V, MacCollin M, et al. Merlin: the neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1423:M29–M36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(99)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stawski R, Piaskowski S, Stoczynska-Fidelus E, et al. Reduced expression of ELAVL4 in male meningioma patients. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2013;30:160–166. doi: 10.1007/s10014-012-0117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Peyre M, Kalamarides M. Molecular genetics of meningiomas: Building the roadmap towards personalized therapy. Neurochirurgie. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thompson LDR, Wieneke JA, Miettinen M. Sinonasal tract melanomas: A clinicopathologic study of 115 cases with a proposed staging system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:594–611. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wenig BM, Vinh TN, Smirniotopoulos JG, et al. Aggressive psammomatoid ossifying fibromas of the sinonasal region. A clinicopathologic study of a distinct group of fibro-osseous lesions. Cancer. 1995;76:1155–1165. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951001)76:7<1155::AID-CNCR2820760710>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]