Abstract

Objective

To prospectively assess women's risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and of experiencing post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) over 4 years after seeking an abortion, and to assess whether symptoms are attributed to the pregnancy, abortion or birth, or other events in women's lives.

Design

Prospective longitudinal cohort study which followed women from approximately 1 week after receiving or being denied an abortion (baseline), then every 6 months for 4 years (9 interview waves).

Setting

30 abortion facilities located throughout the USA.

Participants

Among 956 women presenting for abortion care, some of whom received an abortion and some of whom were denied due to advanced gestational age; 863 women are included in the longitudinal analyses.

Main outcome measures

PTSS and PTSD risk were measured using the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD). Index pregnancy-related PTSS was measured by coding the event(s) described by women as the cause of their symptoms.

Analyses

We used unadjusted and adjusted logistic mixed-effects regression analyses to assess whether PTSS, PTSD risk and pregnancy-related PTSS trajectories of women obtaining abortions differed from those who were denied one.

Results

At baseline, 39% of participants reported any PTSS and 16% reported three or more symptoms. Among women with symptoms 1-week post-abortion seeking (n=338), 30% said their symptoms were due to experiences of sexual, physical or emotional abuse or violence; 20% attributed their symptoms to non-violent relationship issues; and 19% said they were due to the index pregnancy. Baseline levels of PTSS, PTSD risk and pregnancy-related PTSS outcomes did not differ significantly between women who received and women who were denied an abortion. PTSS, PTSD risk and pregnancy-related PTSS declined over time for all study groups.

Conclusions

Women who received an abortion were at no higher risk of PTSD than women denied an abortion.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, ABORTION, PREGNANCY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Unlike prior studies, this study uses an appropriate comparison group, by comparing women who have had an abortion with women who want an abortion but are unable to get one.

This study allowed women to describe in their own words all the possible events in their lives that they believe caused their post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), in order to identify whether the abortion or pregnancy or other factors were perceived to be the source of their symptoms.

This study controls for pre-existing mental health conditions and history of trauma and abuse—factors known to be important predictors of future post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The high rate of participant retention over time, the lack of differences between the main study groups at baseline, the lack of differential loss to follow-up, and the similar results obtained from a sensitivity analyses that excluded sites with a low participation rate, strengthen the validity of our findings.

While we used a standardised PTSD screening measure, findings from this study are limited to PTSS.

Introduction

For the past three decades, claims that abortion causes post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or a ‘post-abortion trauma syndrome’ have been at the heart of political debates and legislation to mandate preabortion counselling, and dissuade women from having wanted abortions.1 2 Scientifically sound studies examining the relationship between abortion and subsequent PTSD have concluded that there is no evidence that abortion causes PTSD in settings where abortion is voluntary, safe and legal,2 3 yet, they have also highlighted the need for more rigorous, prospective studies that account for factors that may influence the PTSD response,4 5 such as prior mental health conditions and lifetime experiences of abuse and violence.6 7

One recent review of studies on abortion and mental health outcomes concluded a causal relationship between abortion and PTSD.8 This review did not conduct a quality analysis of the studies included, nor did it address the findings from previous reviews on the topic, discuss the biases introduced when studies do not control for pre-existing disorders and other known confounders, or critique the absence of appropriate comparison groups. An appropriate comparison group would situate abortion within the context of women's experience of an unplanned pregnancy. Often studies compare women having abortions to women having intended pregnancies that end in childbirth or miscarriage.4 9 Comparing women with pregnancies they wish to carry to term to those with pregnancies they want to terminate is problematic because the circumstances that lead women to the decision to terminate a pregnancy versus parent are inherently different. The recommended comparison group, it has been suggested, is one where women who have an abortion are compared to those wanting an abortion but are unable to get one.10

When PTSD is addressed specifically, many studies frame the abortion as an inherently traumatic experience by assuming that all symptoms following an abortion or pregnancy are caused by the abortion or pregnancy. These studies do not allow the participant to identify other events that they perceived to have caused their symptoms as prescribed in the original measures.9 11–16 The use of PTSD measures in this way contributes to the misattribution of abortion or other pregnancy event as traumatising by ignoring the possibility that participants’ PTSD symptoms may have another cause unrelated to the abortion or pregnancy. One recent study in Sweden found that few women experience PTSD or post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in the year following an abortion, most of which was due to traumatic experiences unrelated to the abortion.17

This paper aims to prospectively assess women's risk for PTSD and of experiencing PTSS over 4 years after seeking an abortion. This study will test the hypothesis that women who receive abortions are more likely to experience PTSS than women who are denied abortions. We will also explore whether the source of women's PTSS is attributed to the pregnancy, abortion or birth, or other events in women's lives, as expressed in women's own words. We report on findings from the Turnaway Study, a 5-year longitudinal study specifically designed to assess the mental health effects of abortion on women's lives, by comparing women who seek and have an abortion with women who seek, yet are denied abortion.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study received ethical approval from the University of California, San Francisco Committee of Human Research. All study participants gave written consent to be in this study.

Study design

This analysis includes the first 4 years, or nine waves of interview data from The Turnaway Study. Study details including an evaluation of participant recruitment strategies have been described elsewhere.18–20 Women were first interviewed by telephone 8 days after having or being denied an abortion, and then every 6 months for 5 years.

In the USA, each abortion facility sets its own gestational age limit. While the upper limit is often set by state law, facilities can adopt a lower gestational limit. This results in great variation in gestational age limits across facilities throughout the USA.21 Abortion facilities with the latest gestational age limit of any other facility within 150 miles were eligible to participate as a recruitment site. Using data from the National Abortion Federation and contacts within the research community, 31 abortion facilities were identified and all but two agreed to participate. One facility was replaced with a facility with a similar catchment area and similar patient volume. The gestational age limits of the 30 final participating facilities’ ranged from 10 weeks through the end of the second trimester. These facilities were located in 21 states throughout the USA.

Study participants

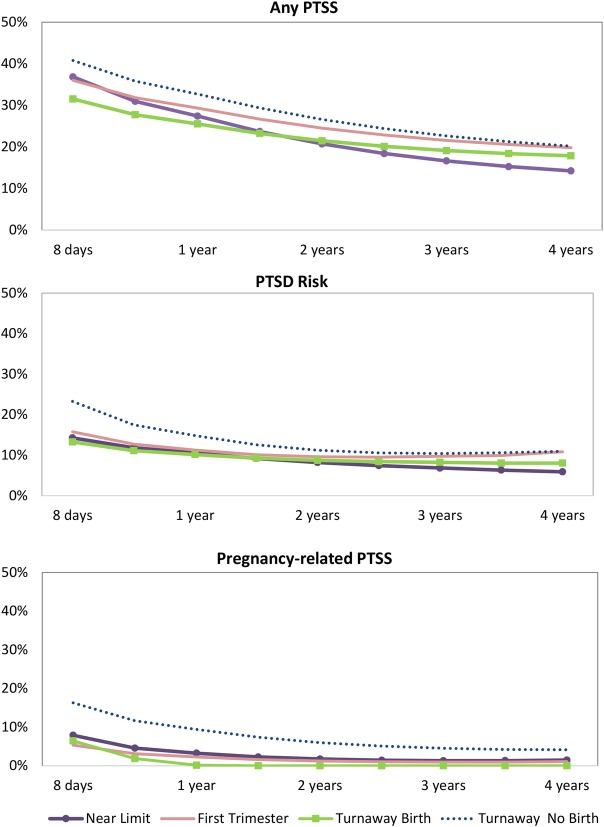

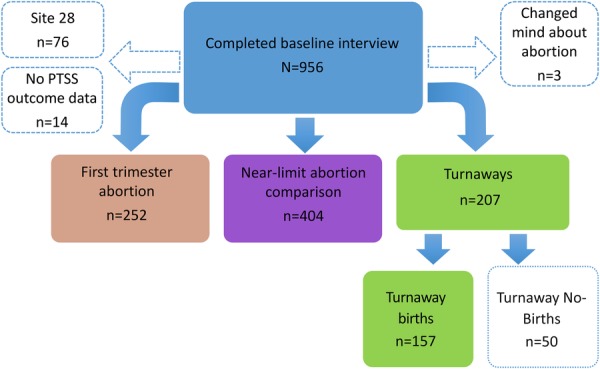

Study participants include English-speaking or Spanish-speaking women presenting for abortion care from January 2008 to December 2010, ages 15 years and older, with no known fetal anomalies or demise or maternal health indications for abortion. Study groups were recruited in a 2:1:1 ratio and include the Near-limit abortion group—women presenting for abortion up to 2 weeks under a facility's gestational limit and receiving abortions (n=452); Turnaway group—women presenting for abortion up to 3 weeks over a facility's gestational limit and denied abortion (n=231); and the First-trimester abortion group—women who received a first trimester abortion (n=273). The Turnaway group was further divided into those who gave birth (Turnaway-births) and those who miscarried or later went on to have an abortion elsewhere (Turnaway-no-births) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sample by study group. PTSS, post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Measures

At approximately 1 week, and every 6 months after receiving or being denied an abortion, participants completed an in-depth, structured interview by telephone. The interview contained questions about a range of topics including employment, health, childbearing experiences and intentions, traumatic life events, and mental health symptoms.

Outcomes variables

We used the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD), a validated screening tool designed to be used in primary care and other medical settings,22 as an indicator of PTSD risk. This measure included an introductory sentence: “In your life, have you ever had any experience that was so frightening, horrible, or upsetting that, in the past month, you”: followed by four questions requiring a ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘don't know’ response. These four questions included: ‘Have had nightmares about it or thought about it when you didn't want to?’, ‘Tried hard not to think about it or went out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of it?’, ‘Were constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled?’ and ‘Felt numb or detached from others, activities or your surroundings?’ Those answering ‘yes’ to three or four items are considered by the authors of the measure to be at risk of PTSD and should be further assessed with a structured interview for diagnosis. Participants were also asked to describe in their own words the event(s) that were so upsetting, and to indicate the date(s) or age(s) when these events occurred.

The PC-PTSD was used as an outcome measure in three ways: (1) any post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), a dichotomous measure indicating whether women reported one or more symptoms of post-traumatic stress, (2) at risk of PTSD, a dichotomous measure of the proportion reporting ‘yes’ on three or four items, regardless of the type of event or when the event occurred and (3) pregnancy-related PTSS, a dichotomous measure of attributing PTSS to the index pregnancy, abortion or birth (see ‘Coding of PTSS events’ in the data analysis section for an explanation of how this variable was constructed).

Primary predictor variables

Study group served as our primary predictor variable of interest and included four categories: (1) Near-limits which served as the reference group, (2) Turnaway-births which served as our main comparison group and was evaluated separately from (3) Turnaway-no-births to isolate the effect of carrying a pregnancy to term, and (4) First-trimesters which served as a secondary comparison group, assessing whether having a first-trimester abortion, the most typical experience of abortion in the USA,23 differs from having an abortion near a facility's gestational age limit.23 Time was measured in years since receiving or being denied an abortion.

Covariates were used to adjust for potential confounding factors known to be associated with PTSD. Covariates included age (continuous), race/ethnicity (white, black, Latina/Hispanic, other), marital status (never married, married and separated, divorced or widowed), education (less than a high school diploma, high school diploma or equivalent, some college or technical school, and college degree), employed (yes/no), marital status (single, married, divorced/widowed), parity (zero births, 1 previous birth, 2 previous births, and 3 or more prior births), history of sexual assault or rape (yes/no), experienced psychological or physical abuse from a partner in the past year (yes/no), history of child abuse/neglect (yes/no), history of a depression or anxiety diagnosis (yes/no), drug use prior to pregnancy recognition (yes/no), and problem alcohol use (either drinking first thing in the morning or not being able to remember what happened the night before) prior to pregnancy recognition. Details about these variables have been described previously.24–26

Data analysis

Coding PTSS events

All open-ended responses to describe the event(s) attributed to the participants’ PTSS, were qualitatively coded by two of the study authors (MAB and BR). A non-hierarchical list of themes was generated and revised iteratively, by both researchers after reviewing all first-wave interview responses. Once the final set of themes was generated after review of all baseline responses, both researchers recoded all the responses until reaching consensus on all items. When the event described was pregnancy-related, abortion-related, or birth-related, the dates when the event(s) occurred, or the age of the participant when the event(s) occurred, was used to verify whether the event was referring to the index pregnancy. All nine interview waves were similarly reviewed and coded to identify the proportion of participants over time indicating that their PTSS were due to the index pregnancy. All coding was done in Excel.

Baseline analyses

Baseline analyses included comparisons of demographic characteristics and PTSS source by study group (tables 1 and 2). Statistically significant differences by study group 1 week after abortion receipt or denial were assessed using mixed-effects regression analyses to accommodate for clustering by facility. Mixed-effects logistic regression was used for dichotomous variables, mixed-effects linear regression for continuous variables, and mixed-effects multinomial regression for multiclass variables, with a postestimation command to assess overall study group differences.

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics by study group

| Near-limits abortion | First-trimester abortion* | Turnaway- birth* | Turnaway-no- births* | Total | p Value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | (n=404) | (n=252) | (n=157) | (n=50) | (N=863) | |

| Age, year, mean±SD | 24.9±5.9 | 25.9±5.7‡ | 23.5±5.6‡ | 24.5±6.2 | 24.9±5.8 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ‡ | 0.059 | ||||

| White | 32 | 39 | 25 | 42 | 33 | |

| Black | 32 | 32 | 34 | 28 | 32 | |

| Hispanic/Latina | 21 | 21 | 27 | 14 | 22 | |

| Other | 15 | 8 | 13 | 16 | 13 | |

| Highest level of education, % | 0.313 | |||||

| Less than high school | 19 | 16 | 24 | 20 | 19 | |

| High school or GED | 34 | 31 | 34 | 26 | 33 | |

| Some college, associates or technical school | 40 | 42 | 36 | 46 | 40 | |

| College degree | 7 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 8 | |

| Employed, % | 54 | 63‡ | 39‡ | 48 | 54 | <0.001 |

| Marital status, % | 0.396 | |||||

| Single | 79 | 77 | 83 | 78 | 79 | |

| Married | 8 | 11 | 10 | 6 | 9 | |

| Divorced/widowed | 13 | 13 | 6 | 16 | 12 | |

| Pregnancy-related characteristics | ||||||

| Gestational age, weeks, mean±SD | 19.9±4.1 | 7.8±2.4‡ | 23.4±3.4‡ | 19.2±4.0‡ | 17.0±7.0 | <0.001 |

| Parity, % | 0.226 | |||||

| 0 previous births | 34 | 38 | 47 | 40 | 38 | |

| 1 previous birth | 30 | 23 | 21 | 28 | 26 | |

| 2 previous births | 18 | 20 | 17 | 20 | 19 | |

| 3 or more previous births | 18 | 18 | 15 | 12 | 17 | |

| History of abuse, sexual assault, intimate partner violence and substance use, % | ||||||

| Child/abuse neglect | 27 | 27 | 26 | 14 | 26 | 0.197 |

| History of sexual assault or rape | 21 | 23 | 21 | 18 | 21 | 0.646 |

| Experienced physical or psychological violence from an intimate partner in the past year | 23 | 24 | 17 | 12 | 22 | 0.121 |

| Any illicit drug use before discovering pregnancy | 13 | 17 | 14 | 8 | 14 | 0.219 |

| Problem alcohol use before discovering pregnancy | 4 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 0.215 |

| Mental health | ||||||

| History of depression or anxiety disorder | 24 | 30 | 21 | 30 | 26 | 0.230 |

| PTSD screen, mean±SD, % | 0.85±1.26 | 0.92±1.32 | 0.86±1.24 | 0.98±1.45 | 0.88±1.28 | 0.848 |

| 0 symptoms (not at risk) | 62 | 60 | 60 | 62 | 61 | |

| 1–2 symptoms (not at risk) | 23 | 23 | 24 | 20 | 23 | |

| 3–4 symptoms (at risk) | 15 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 16 | 0.990 |

*When compared to Near-limits abortion group.

†Global comparison test.

‡p<0.05.There were no missing responses for any of the variables presented, except for reports on problem alcohol use which had three missing responses.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 2.

Events attributed to have caused baseline PTSS

| Among women with PTSS, % |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Near-limits abortion | First-trimester | Turnaway-birth | Turnaway-no-birth | Total | Among women at risk of PTSD (n=139) | Among all women (N=863) | |

| Source of PTSS | (n=155) | (n=101) | (n=63) | (n=19) | (n=338) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Violence, abuse or unlawful activity | 25 | 39* | 32 | 21 | 30 | 61 (44) | 101 (12) |

| Sexual, physical or emotional abuse, including sexual assault (not partner) | 11 | 16 | 17 | 11 | 14 | 23 (17) | 46 (5) |

| Intimate partner violence | 7 | 11 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 29 (14) | 28 (3) |

| Witnessing or loved one experiencing a violent event, including suicide or violent death | 5 | 9 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 13 (9) | 23 (3) |

| Unlawful activity or violent fight (not partner) | 5 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 10 (7) | 15 (2) |

| Non-violent relationship issues | 22 | 18 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 23 (17) | 69 (8) |

| Partner (eg, divorce, breakup, partner jail time) | 15 | 14 | 11 | 21 | 15 | 17 (12) | 49 (6) |

| Family or friend | 7 | 5 | 13 | 0 | 7 | 8 (6) | 24 (3) |

| Problem substance use of loved ones (family, friend, partner) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 (1) | 36 (4) |

| Index pregnancy-related event | 21 | 14 | 17 | 32 | 19 | 19 (14) | 64 (7) |

| Abortion experience or decision | 14 | 8 | 5 | 16 | 11 | 8 (6) | 36 (4) |

| Pregnancy experience | 3 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 6 | 6 (4) | 19 (2) |

| Others’ reaction to pregnancy/abortion, reminded of abortion | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 (2) | 7 (<1) |

| Index pregnancy result of rape | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 2 (1) | 4 (<1) |

| Non-violent death/illness of a loved one | 18 | 14 | 10 | 16 | 15 | 22 (16) | 51 (6) |

| Personal health-related issues including substance use and mental health | 8 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 10 (7) | 20 (2) |

| Emotional/mental health issues | 6 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 (3) | 13 (2) |

| Drug/alcohol abuse | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 (2) | 5 (<1) |

| Illness/other | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 (2) | 3 (<1) |

| Prior pregnancy or abortion experience | 4 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 3 (2) | 15 (2) |

| Concerns about children, parenting, custody issues | 5 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 7 (5) | 13 (2) |

| Financial/job/housing insecurity | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 (3) | 13 (2) |

| Accident | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 7 (5) | 13 (2) |

| Other | 4 | 5 | 8 | 16 | 6 | 8 (6) | 19 (2) |

*p<0.05 when compared to Near-limit abortion group.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; PTSS, post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Longitudinal analysis

The main statistical analyses assessed the trajectories of our three main outcomes (PTSS, PTSD risk and pregnancy-related PTSS), and whether these differed by study group, using mixed-effects logistic regression analyses. These models are designed to handle missing data and allow the inclusion of all observations even when some participants have missing observations.27 For all three outcomes we first included only study group, time (years) and study group by time interactions. The group by time interactions are used to assess study group differences in outcome trajectories. A significant group by time interaction (p<0.05) indicates that the trajectory for that study group differs significantly from the trajectory of the Near-limits which served as our reference group. When study group is significant at p<0.05, this indicates that at baseline, that study group differs significantly from Near-limits with regard to the model outcome. The second set of analyses additionally adjusted for baseline covariates that could potentially confound the relationship between study group and our outcomes. Gestational age was not included as a covariate because it is closely aligned with the study group by virtue of the study design; women in the Near-limit group were recruited just under each recruitment facility's gestational age limit, and Turnaways were recruited just over each facility's gestational age limit, resulting in little variation in gestational ages within each study group. In order to assess the effects of gestational age on our study outcomes, we compare women in the First-trimester group with women in the Near-limit group. All analyses accounted for clustering at the level of site and individual. When random slopes for individuals and quadratic terms for time improved the model fit as indicated by a significant (p<0.05) likelihood ratio test, these (years2, and study group × years2) were also included in the model.28 To graph model results, we used the margins command in Stata V.14 to estimate the marginal probability of each of our three outcomes for each of the study groups at approximately 6-month intervals, averaging over the covariate patterns in the sample. Using this same command, we estimated study group differences at the end of the study period for each of our three outcomes.

We conducted two sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results. The first set limited all analyses to the 402 women from the seven sites, with a recruitment participation rate of 50% or greater. The second set excluded the 15 women who placed their babies for adoption. All analyses were performed using STATA V.14.

Results

Study sample

A total of 956 women completed baseline interviews, representing a participation rate of 37.5% of eligible women who consented to participate. Of participants who completed a baseline interview 1 week after abortion seeking, 92% (n=880) were retained at the 6-month follow-up, 76% (n=727) at 2 years, 68% (n=653) at 3 years, and 65% (n=618) were retained at 4 years. Rates of attrition at 4 years did not differ significantly by study group. Baseline levels of PTSS and risk, and history of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation were not associated with loss to follow-up. One study site (n=76) was dropped from all analyses because 95% of their Turnaways went on to receive an abortion elsewhere. Three participants originally intending to have an abortion on recruitment, later reported that they had not had an abortion, and were excluded from the final sample. Fourteen participants were dropped because they had missing responses on the PTSD questions, leaving a final sample of 863 participants. Among the 207 remaining Turnaways, 44 received an abortion elsewhere and six reported having a miscarriage (Turnaway-no-births) later. The final four study groups included 404 Near-limits, 157 Turnaway-births, 50 Turnaway-no births, and 252 First-trimesters (figure 1).

Description of the sample

Baseline sample characteristics are presented in table 1. Number of PTSS, educational level, parity, marital status, history of depression/anxiety, child abuse/neglect, history of sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and substance use were similar across groups. By design, gestational age at recruitment differed across study groups. Turnaway-births were younger (mean=23.5 years) and First-trimesters were older (mean=25.9 years) relative to Near-limits. The racial/ethnic composition of the First-trimester group differed significantly from the Near-limit abortion group. Turnaway-births were less likely (39%) and First-trimesters more likely to be employed (63%) when compared with Near-limits (54%).

Two in five women reported any PTSS (39%) at the baseline interview. A quarter (23%) reported one or two symptoms, and less than one-fifth (16%) reported three or more symptoms, indicating risk for PTSD. There were no significant differences in baseline PTSS or risk by study group—15% of Near-limits, 17% of the Turnaway-births, 18% of Turnaway-no-births and 17% of First-trimesters were at risk of PTSD, 1 week after receiving or being denied an abortion.

Source of PTSS at baseline, 1 week after abortion seeking

Women reported a wide range of experiences that they perceived to have caused their PTSS. The events described at baseline fell into 10 broad themes. Among those with any symptoms, violence, abuse or criminal activity was most often mentioned as a source of symptoms (30%), followed by non-violent relationship issues (20%), index pregnancy-related event (19%), non-violent death or illness of a loved one (15%), and personal health-related issues (6%) (table 2). Only one source of symptoms differed significantly by study group. Women in the First-trimester group (39%) were significantly more likely to mention violence, abuse or criminal activity as the source of their PTSS than Near-limits (25%). The most common source of symptoms among the 139 women who may be considered at risk of PTSD at baseline was violence, abuse or unlawful activity (44%), followed by non-violent relationship issues (17%), and non-violent death or illness of a loved one (16%). Among those at risk, women in the First-trimester group (58%) were significantly more likely to mention violence, abuse or criminal activity as the source of their PTSS than Near-limits (34%); Turnaway-no-births (22%) were significantly more likely to mention a general or vague event as the source of their symptoms than Near-limits (3%) (not shown). Approximately 14% of women at risk, or 7% of the full sample, pointed to the index pregnancy as the source of their PTSS, with no significant differences by study group.

Violence, abuse or criminal activity

The most common perceived cause of PTSS at baseline was related to violence, abuse or criminal activity, mentioned by 30% of respondents. Fourteen per cent (n=46) of respondents cited a history of sexual, physical or emotional abuse, such as being raped or sexually assaulted by a non-partner (n=28), and experiencing childhood sexual, emotional or physical abuse (n=28) as the source of their PTSS.

Eight per cent (n=28) of women reported intimate partner violence as the source of their symptoms. A 28-year-old explained: “I was in a very abusive relationship for 4.5 years. He strangled me and put me in a coma for 2 weeks. He called me from prison 2 nights before the interview and told me he loves me. He is the father of my son.” Another woman, age 29, described the source of her distress: “My son's father…started doing drugs and he hit me and knocked my front two teeth out and then we was dealing drugs out of our house, the house was raided and I ended up going to jail for 9 months. Everything in my life has been ruined by him.”

Seven per cent (n=23) of women described witnessing a violent event, or described a violent event experienced by a loved one as the source of their PTSS. Several, for example, described the unlawful deaths of loved ones ‘friend was stabbed in my house’, ‘my cousins were shot and a friend died’ and ‘mom was murdered, younger sister also murdered’. Knowing family members or friends who attempted suicide as a source of distress was also described. A 23-year-old with three kids under the age of three mentions: “My first two children are by my ex-husband who ended his life in front of us.” A 27-year-old woman who sought an abortion ‘not only for myself but for my kids’ describes her ex-husband who ‘tried to commit suicide three times’, and points to the ‘incident…when [he] tried to commit suicide in my house’ as the cause of her PTSS.

Four per cent (n=15) of women reported the experience of a violent event, such as being involved in a fight, attack, robbery ‘house was raided’, ‘home invasion’, criminal activity ‘went to court for a felony’ and/or imprisonment as the source of their symptoms. A 28-year-old woman with two sons described: “When I was 19 I was kept in a room against my will and I was beaten and tortured for 3 days” as the reason why she was experiencing PTSS. A 20-year-old woman similarly described being ‘locked in a basement for a week’ as the source of her symptoms.

Index pregnancy-related event

Among those who attributed their symptoms to the index pregnancy experience (n=64), many (n=19) succinctly stated that ‘the abortion’ was the source of their symptoms. Three women referred specifically to the decision to have an abortion: “The actual decision to have the abortion. To know the baby’s not going to be here and there was a baby” as the reason behind their distress. Others reported that the experience of getting an abortion or the abortion procedure was the reason they were experiencing symptoms, ‘the abortion clinic experience’, ‘seeing anti-abortion protestors’. Twenty respondents attributed their PTSS to the pregnancy experience: “Finding out I was pregnant because I was nervous and had all the sickness and was always at home,” “Just feeling overwhelmed about being pregnant.” Four respondents mentioned other people's reaction to their abortion as a cause of distress: “My cousin was against it [the abortion] because she couldn't have a baby. [My] cousin said horrible stuff about it [the abortion] to me.” Three respondents reported that being reminded of the abortion was the source of their symptoms: “Seeing small children makes me feel guilty that I did something wrong. Being around an infant makes me feel like I did something bad.” Five respondents attributed their symptoms to the rape which resulted in the index pregnancy. One respondent attributed her distress to being ‘turned away from the clinic’.

Relationship issues

About one in five women attributed their PTSS to relationship problems other than violence or abuse, such as experiencing challenges with parents ‘situation with my mother’, and other family members ‘family turmoil’, as well as partners ‘break-up’, ‘husband has to go to jail’ and friends ‘losing friends’. Three women attributed their symptoms to the substance use issues of a loved one: “Mother’s drug use, lifestyle we had to live as a result.”

Non-violent death or illness of a loved one

The non-violent death or illness of family or a friend was mentioned as a source of symptoms for 15% (n=51) of women: “My mother finding out she is HIV positive”; “Mother passed away of cancer.”

Personal health-related issues including substance use and mental health

Twenty women (6%) mentioned personal health-related reasons as the source of their PTSS. This took the form of substance use issues: ‘Had a job where I was doing drugs and taking medication from the clients’, ‘I almost died from being on drugs’ or general mental health concerns: ‘I have a lot of anxiety over verbal, physical and sexual abuse’, ‘Not a specific event, part of the depression’, and general health issues ‘Lupus’, ‘I have allergies, so I almost died, I didn’t know if the people around me were going to save me or what, I was done for’.

Concerns about children, parenting and custody issues

Four per cent (n=13) of women pointed to concerns about existing children as the source of their PTSS. These concerns were often related to custody issues or not being able to raise their own kids: “My kids are in foster care, my visits with my kids are very hurtful,” “kids were taken away.” Some women were worried that their children may become the victims of abuse: “I was molested when I was younger, so I’m afraid for my daughter.”

Financial/job/housing insecurity

Financial ‘money problems’, ‘$10 000 in debt’, employment ‘losing and not being able to find work’ and housing concerns, such as being evicted, were mentioned by thirteen (4%) women as a source of PTSS. A 20-year-old woman explained the event that caused her symptoms: “I got laid off from my job and I’m not able to pay my bills. My life isn't going where I want it to go and I’m not achieving where I should be.”

Accidents

Four per cent (n=13) of women with symptoms attributed them to car (3%, n=11) and other accidents (n=2).

Non-specific events

Six per cent (n=19) of responses did not fit into a clear theme or category. These often pointed to a vague or an undefined event for example, ‘just my situation, the situation at the time, it was upsetting’, ‘no particular event’ and ‘I don't really have a specific event’.

PTSS and PTSD risk trajectories

The results of the unadjusted and adjusted mixed-effects logistic regression models comparing trajectories of PTSS, PTSD risk and index pregnancy-related PTSS by study group are presented in tables 3 and 4. The unadjusted models closely mirrored those of the adjusted models. In the adjusted PTSS model we found no significant differences at baseline by study group. As indicated by the significant adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for years (aOR=0.47, 95% CI=0.41 to 0.55), PTSS declined for Near-limits. The lack of significant group by time interactions for the Turnaway-births and Turnaway no-births indicates that PTSS also declined for these two groups over the 4-year period. The significant group by time interaction for the First-trimester abortion group (aOR=1.24, CI 1.01 to 1.52) indicates that their PTSS decline was not as steep when compared to the Near-limits (figure 2). At the end of the 4-year study period, women in the First-trimester group were significantly more likely than women in the Near-limit group to report any PTSS (20% vs 14%, p=0.04). While the group by time interaction only approached statistical significance for the Turnaway-birth group (p=0.06), the proportion of women with PTSS in this group declined more slowly, eventually reaching higher levels than the Near-limits by the end of the 4-year study period (figure 2), although the difference between these two groups was not statistically significant at year 4 (p=0.23).

Table 3.

Longitudinal unadjusted logistic random effects regression analyses predicting any PTSS, PTSD risk and pregnancy-related PTSS (n=863), based on 6012 observations

| Any PTSS (1–4 symptoms) | At risk of PTSD (3–4 symptoms) | Pregnancy-related PTSS |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | OR | 95% CI |

OR | 95% CI |

OR | 95% CI |

|||

| Study group | |||||||||

| Near-limit abortion (reference) | |||||||||

| First-trimester abortion | 1.03 | 0.68 | 1.57 | 1.36 | 0.75 | 2.47 | 0.57 | 0.24 | 1.32 |

| Turnaway-births | 0.69 | 0.42 | 1.13 | 0.81 | 0.39 | 1.69 | 0.76 | 0.26 | 2.18 |

| Turnaway-no-births | 0.98 | 0.44 | 2.18 | 1.89 | 0.65 | 5.51 | 2.54 | 0.73 | 8.82 |

| Years | 0.45* | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.61* | 0.37 | 1.00 | 0.22* | 0.11 | 0.42 |

| First-trimester abortion ×years | 1.25* | 1.02 | 1.54 | 0.81 | 0.40 | 1.64 | 1.12 | 0.36 | 3.55 |

| Turnaway-births × years | 1.25 | 0.98 | 1.61 | 1.15 | 0.48 | 2.73 | 3.97 | 0.00 | 7971.06 |

| Turnaway-no-births × years | 1.20 | 0.80 | 1.80 | 0.63 | 0.17 | 2.32 | 1.60 | 0.32 | 7.86 |

| Years × years | 0.91 | 0.80 | 1.03 | 1.27* | 1.07 | 1.50 | |||

| First-trimester abortion × years2 | 1.13 | 0.94 | 1.35 | 0.98 | 0.73 | 1.33 | |||

| Turnaway-births × years2 | 1.02 | 0.81 | 1.27 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 562.51 | |||

| Turnaway-no-births × years2 | 1.16 | 0.83 | 1.64 | 0.90 | 0.58 | 1.38 | |||

*p<0.05.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; PTSS, post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Table 4.

Longitudinal adjusted random effects logistic regression analyses predicting any PTSS, PTSD risk and pregnancy-related PTSS (n=863), based on 6012 observations

| Any PTSS (1–4 symptoms) | At risk of PTSD (3–4 symptoms) |

Pregnancy-related PTSS |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR |

95% CI | aOR |

95% CI | aOR |

95% CI | ||||

| Predictor variables | |||||||||

| Study group | |||||||||

| Near-limit abortion (reference) | |||||||||

| First-trimester abortion | 0.94 | 0.63 | 1.39 | 1.21 | 0.68 | 2.14 | 0.56 | 0.24 | 1.29 |

| Turnaway-births | 0.68 | 0.42 | 1.09 | 0.85 | 0.42 | 1.71 | 0.72 | 0.25 | 2.06 |

| Turnaway-no-births | 1.31 | 0.63 | 2.73 | 2.49 | 0.92 | 6.79 | 3.38 | 0.99 | 11.57 |

| Years | 0.47* | 0.41 | 0.55 | 0.61* | 0.38 | 0.99 | 0.21* | 0.11 | 0.41 |

| First-trimester abortion × years | 1.24* | 1.01 | 1.52 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 1.64 | 1.14 | 0.36 | 3.62 |

| Turnaway-births × years | 1.26 | 0.99 | 1.61 | 1.07 | 0.45 | 2.55 | 3.89 | 0.00 | 8209.77 |

| Turnaway-no-births × years | 1.16 | 0.78 | 1.71 | 0.63 | 0.17 | 2.25 | 1.52 | 0.32 | 7.27 |

| Years × years | 0.91 | 0.80 | 1.04 | 1.27* | 1.07 | 1.51 | |||

| First-trimester abortion × years2 | 1.13 | 0.94 | 1.35 | 0.98 | 0.72 | 1.33 | |||

| Turnaway-births × years2 | 1.03 | 0.83 | 1.29 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 613.22 | |||

| Turnaway-no-births × years2 | 1.16 | 0.83 | 1.61 | 0.91 | 0.60 | 1.38 | |||

| Control variables | |||||||||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 1.08 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White (reference) | |||||||||

| Black | 1.09 | 0.72 | 1.64 | 1.43 | 0.87 | 2.37 | 3.19* | 1.47 | 6.92 |

| Hispanic/Latina | 1.15 | 0.73 | 1.82 | 0.98 | 0.56 | 1.71 | 4.15* | 1.76 | 9.80 |

| Other | 1.13 | 0.68 | 1.87 | 1.16 | 0.63 | 2.13 | 0.93 | 0.31 | 2.80 |

| Highest level of education | |||||||||

| <High school (reference) | |||||||||

| High school or GED | 1.54 | 0.99 | 2.40 | 1.45 | 0.85 | 2.50 | 1.25 | 0.56 | 2.78 |

| Associates or technical degree or some college | 1.62* | 1.03 | 2.53 | 1.64 | 0.95 | 2.83 | 0.93 | 0.41 | 2.11 |

| College | 0.95 | 0.46 | 1.95 | 1.61 | 0.67 | 3.87 | 0.94 | 0.24 | 3.71 |

| Employed | 0.68* | 0.50 | 0.94 | 0.55* | 0.38 | 0.82 | 1.25 | 0.70 | 2.22 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single (reference) | |||||||||

| Married | 1.42 | 0.83 | 2.44 | 1.22 | 0.64 | 2.36 | 0.75 | 0.24 | 2.33 |

| Divorced/widowed | 1.75* | 1.06 | 2.87 | 1.43 | 0.80 | 2.54 | 0.75 | 0.28 | 2.03 |

| Parity | |||||||||

| 0 previous births (reference) | |||||||||

| 1 previous birth | 1.14 | 0.77 | 1.71 | 1.28 | 0.78 | 2.10 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 1.06 |

| 2 previous births | 1.00 | 0.62 | 1.60 | 1.09 | 0.61 | 1.95 | 0.37* | 0.15 | 0.90 |

| 3 or more previous births | 0.89 | 0.52 | 1.52 | 1.19 | 0.62 | 2.27 | 0.24* | 0.09 | 0.68 |

| Child/abuse neglect | 2.14* | 1.35 | 3.40 | 2.11* | 1.23 | 3.62 | 1.45 | 0.63 | 3.33 |

| History of sexual assault or rape | 2.35* | 1.44 | 3.81 | 2.38* | 1.38 | 4.11 | 1.25 | 0.53 | 2.94 |

| Experienced physical or psychological violence from an intimate partner in the past year | 2.49* | 1.73 | 3.60 | 2.57* | 1.68 | 3.93 | 0.82 | 0.40 | 1.66 |

| Any drug use before discovering pregnancy | 1.37 | 0.89 | 2.13 | 1.14 | 0.68 | 1.92 | 0.93 | 0.40 | 2.12 |

| Problem alcohol use | 1.54 | 0.82 | 2.89 | 1.07 | 0.51 | 2.25 | 0.39 | 0.09 | 1.62 |

| Previous anxiety of depression diagnosis | 2.62* | 1.82 | 3.76 | 3.34* | 2.19 | 5.09 | 2.75* | 1.41 | 5.38 |

*p<0.05. There were no missing responses for any of the variables except for reports on problem alcohol use which had 3 missing responses.

aOR, adjusted OR; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; PTSS, post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Figure 2.

Marginal predicted probabilities of experiencing post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) risk 4 years after seeking or being denied abortion, by study group (n=863): based on adjusted mixed-effects logistic regression analyses.

Baseline levels and 4-year trajectories of PTSD risk did not differ significantly by study group. Although not reaching statistical significance, the Turnaway-no-birth group was at somewhat higher risk of PTSD at baseline (p=0.07 in the adjusted model). Risk of PTSD for all groups declined steadily over the 4-year study period (aOR 0.61, CI 0.38 to 0.99) (tables 3 and 4 and figure 2). At year 4, women in the First-trimester group were significantly more likely to be at risk of PTSD when compared to women in the Near-limit group (10% vs 6%, p=0.03, in the adjusted model). Previous experiences of trauma (child abuse/neglect, history of sexual assault/rape, intimate partner violence, and previous anxiety or depression diagnosis) were more significant predictors of PTSS and PTSD risk than study group.

In the adjusted model predicting pregnancy-related PTSS, women denied an abortion who went on to give birth (Turnaway-births), Turnaway-no-births, and women in the First-trimester abortion group were no more or less likely to attribute their PTSS at baseline to the index pregnancy than women in the Near-limit group. Across study groups, pregnancy-related PTSS declined significantly over time, with no significant differences in trajectories by study group (tables 3 and 4 and figure 2). At year 4, women in the Near-limit group were significantly more likely to attribute the source of their PTSS to the index pregnancy than women in the Turnaway-Birth group (0% vs 1.5%, p=0.03). Significant predictors of having pregnancy-related PTSS are a previous anxiety or depression diagnosis (aOR=2.75), and being African-American (aOR=3.19) or Latina (aOR=4.15). Women with more than one previous child were significantly less likely to report pregnancy-related PTSS. Among the women who had an abortion (Near-limits and First-trimesters) and reported pregnancy-related PTSS at baseline, 92% reported that they felt having the abortion was the right decision. By the end of the study period, four of the seven women who reported the index pregnancy as the source of their PTSS still felt the abortion was the right decision for them (not shown in table).

Results from the two sensitivity analyses were essentially equivalent to our main findings.

Discussion

Our study findings do not support the hypothesis that women obtaining abortions are more likely to experience PTSS than women who are denied abortions and must carry their unwanted pregnancies to term. This study improves on the previous literature on abortion and mental health by comparing the psychological outcomes of two groups of abortion-seeking women—one able to obtain their abortion, and the other denied a wanted abortion. By following these women over 4 years, we were able to assess whether women obtaining abortions are more likely to develop PTSS than women denied an abortion. Unlike other studies, this study allowed women to express, in their own words, the nature of events that they believe caused their PTSS; women themselves identified whether the abortion or pregnancy experience or other events in their lives resulted in adverse psychological outcomes. Given the similarity of our sample demographics to the population of women in the USA obtaining abortions, we believe our results are generalisable to settings where abortion is legal and safe.29 These results, however, should not be generalised to contexts where abortion is illegal or unsafe, or to women seeking abortion due to fetal anomaly, as these women were excluded from this study.

Women pointed to a range of traumatic life experiences as the source of their symptoms. Other studies have suggested that exposure to sexual and physical assaultive violence poses the greatest risk of experiencing future PTSD, a finding that was echoed in this study.30 31 One in five women reported a history of sexual assault or rape. Childhood and adult experiences of sexual and physical violence and abuse were most often the source of women's symptoms, and accounted for nearly one-third of PTSS. These findings are consistent with several other studies that have also shown that exposure to sexual and physical violence is strongly associated with PTSS and PTSD following abortion.6 17 32 33

This study found that shortly after seeking an abortion, about two in five women experienced one or more symptoms of PTSD, and 16% scored high enough to be considered at risk, with no differences between those obtaining a wanted abortion and those denied one. We found two other studies which use this same PC-PTSD scale. The proportion scoring at risk on the PC-PTSD screen were markedly lower among the women in this study (16%) than among patients from an urban trauma centre (36%)34; average PC-PTSD screening scores were also lower than among Veterans Affairs medical care patients.22

While some women reported that the experience of pregnancy or an abortion caused symptoms of distress, these feelings did not differ initially among those who had the abortion procedure and those denied a wanted procedure, and the proportion was relatively small (7% of the full sample at baseline). The lack of significant differences between those women who had an abortion and those denied abortion care suggests that circumstances around the time of the index pregnancy were the source of distress, rather than the abortion procedure itself. African-American and Latina women were significantly more likely than white women to identify the index pregnancy as the source of their symptoms. This may be a result of greater levels of internalised stigma regarding abortion, although evidence of racial differences in abortion stigma is not well established in the literature.35 36

Earlier studies have suggested that having an abortion at later gestational ages is more traumatic than having an abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy.32 37 Our findings did not support this notion. The lack of statistically significant baseline differences between the Near-limit and First-trimester abortion groups, the less steep decline in symptoms experienced by women in the First-trimester group than women in the Near-limit group, and the greater proportion of First-trimester than Near-limit women with symptoms and at risk of PTSD at year 4, suggests that having an abortion later in pregnancy does not place women at greater risk of adverse mental health outcomes than having an abortion earlier in pregnancy.

One of this study's greatest strengths lies in its use of an appropriate comparison group—women denied a wanted abortion. Recruiting women just below and just above a facility's gestational limit produced very similar study groups. Previous findings from this study indicate that the two main study groups, Near-limits and Turnaways, are very similar on a wide range of relevant indicators. Each group reported similar reasons for delaying abortion care—need to raise money for travel and procedure costs and not recognising the pregnancy, similar levels of difficulty deciding about the abortion, and similar pregnancy intentions.20 18 The lack of study group differences in baseline levels of PTSD symptoms and risk, and history of depression, anxiety, and trauma indicates that the two groups were similar before abortion receipt or denial.

For all groups of women, PTSS, PTSD risk and attributing the index pregnancy as the source of symptoms declined over time. After 4 years, about 1% (n=8) of women seeking abortion pointed to the index pregnancy as a source of symptoms of distress; two of whom may be at risk for PTSD. Despite a low level of risk for PTSD, the small minority of women with symptoms attributed to the index pregnancy remind us that abortion is a personal event and women vary in their responses after abortion. It is important to note that the majority of these women who pointed to the pregnancy or abortion as a source of distress also indicated that the abortion was the right decision for them.

This study has some limitations. Findings from this study are limited to symptoms of PTSD. Without clinical diagnosis, we were unable to assess whether women went on to develop full PTSD. Furthermore, we were unable to precisely identify the source of women's trauma. In-depth qualitative interviews about women's lives would have been better able to explore the coexisting stresses and complex life experiences that may have contributing to symptoms of PTSD. Our data were unable to distinguish which aspects of the abortion, pregnancy or birth were traumatic among women who identified the index pregnancy as the source of their distress. For example, women identifying ‘the abortion’ as the reason behind their symptoms may have been specifically referring to the procedure, difficulty obtaining services, the decision to terminate, internalised stigma around abortion, the circumstances (eg, financial, partner, etc) in their life that resulted in their decision to end the pregnancy, or other factors. Moreover, women's perceptions of the source of their PTSS are likely unable to disentangle the complex factors—personality traits, family history, coping behaviour, and previous manifestations of psychopathology—which are known to be associated with the subsequent development of PTSD.30 Thus, women may have mistakenly misattributed the source of their symptoms.

Another important study limitation is our participation rate of 37.5%. While this level of participation is expected for such a lengthy longitudinal study,38 we cannot exclude the possibility that women with symptoms of PTSD may have been less likely to participate than those without such symptoms. However, we did not identify any differential participation by study group in several baseline measures, including mental health history and history of sexual of physical abuse or violence. When we compared participants from sites with lower levels of participation, participants from sites with higher participation did not differ in age, gestational age, or study group,38 and were not more likely to have higher levels of PTSS post-abortion seeking, mitigating concerns of bias. The high rate of participant retention over time, the similarity between groups at baseline, the lack of differential loss to follow-up, and the similar results obtained from a sensitivity analyses that excluded sites with a low participation rate, strengthen the validity of our findings.

This study is an important contribution to the literature by presenting women's PTSS trajectories over the course of 4 years after seeking abortion, putting them in the context of women's complex lives. Women accessing abortion services reported a wide range of traumatic events which contributed to their PTSS. The index pregnancy did not emerge as the only or main source of women's symptoms and, in fact, pregnancy-related PTSS trajectories and at baseline did not differ by whether the woman received or was denied an abortion. For all groups, PTSS outcomes declined over time.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rana Barar, Heather Gould and Sandy Stonesifer for study coordination and management; Mattie Boehler-Tatman, Janine Carpenter, Undine Darney, Ivette Gomez, C Emily Hendrick, Selena Phipps, Claire Schreiber and Danielle Sinkford for conducting interviews; Michaela Ferrari, Debbie Nguyen and Elisette Weiss for project support; Jay Fraser and John Neuhaus for statistical and database assistance and all the participating providers for their assistance with recruitment.

Footnotes

Contributors: MAB drafted the initial manuscript, coded open-ended responses, and conducted all the quantitative analyses. BR reviewed the literature, cowrote sections of the initial manuscript, coded open-ended responses and reviewed the final manuscript. CEM guided and reviewed all of the statistical methods and interpretation of all statistical results. DGF was the principal investigator of the study, conceived the study, obtained the funding and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by research and institutional grants from the Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004, and an anonymous foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Guttmacher Institute. State policies in brief: counseling and waiting periods for abortion. State policies in brief New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly K. The spread of ‘Post Abortion Syndrome’ as social diagnosis. Soc Sci Med 2014;102:18–25. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson GE, Stotland NL, Russo NF et al. Is there an “abortion trauma syndrome”? Critiquing the evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2009;17:268–90. 10.1080/10673220903149119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charles VE, Polis CB, Sridhara SK et al. Abortion and long-term mental health outcomes: a systematic review of the evidence. Contraception 2008;78:436–50. 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Major B, Appelbaum M, Beckman L et al. Abortion and mental health: evaluating the evidence. Am Psychol 2009;64:863–90. 10.1037/a0017497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tinglöf S, Högberg U, Lundell IW et al. Exposure to violence among women with unwanted pregnancies and the association with post-traumatic stress disorder, symptoms of anxiety and depression. Sex Reprod Healthc 2015;6:50–3. 10.1016/j.srhc.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg JR, Finer LB. Coleman, Coyle, Shuping, and Rue make false statements and draw erroneous conclusions in analyses of abortion and mental health using the National Comorbidity Survey. J Psychiatr Res 2012;46:407–8; discussion 08–11 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellieni CV, Buonocore G. Abortion and subsequent mental health: review of the literature. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2013;67:301–10. 10.1111/pcn.12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rue VM, Coleman PK, Rue JJ et al. Induced abortion and traumatic stress: a preliminary comparison of American and Russian women. Med Sci Monit 2004;10:SR5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stotland NL. Induced abortion and adolescent mental health. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2011;23:340–3. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32834a93ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broen AN, Moum T, Bødtker AS et al. The course of mental health after miscarriage and induced abortion: a longitudinal, five-year follow-up study. BMC Med 2005;3:18 10.1186/1741-7015-3-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broen AN, Moum T, Bödtker AS et al. Psychological impact on women of miscarriage versus induced abortion: a 2-year follow-up study. Psychosom Med 2004;66:265–71. 10.1097/01.psy.0000118028.32507.9d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curley M, Johnston C. The characteristics and severity of psychological distress after abortion among university students. J Behav Health Serv Res 2013;40:279–93. 10.1007/s11414-013-9328-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Congleton GK, Calhoun LG. Post-abortion perceptions: a comparison of self-identified distressed and nondistressed populations. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1993;39:255–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broen AN, Moum T, Bödtker AS et al. Reasons for induced abortion and their relation to women's emotional distress: a prospective, two-year follow-up study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005;27:36–43. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman PK, Coyle CT, Shuping M et al. Induced abortion and anxiety, mood, and substance abuse disorders: isolating the effects of abortion in the national comorbidity survey. J Psychiatr Res 2009;43:770–6. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallin Lundell I, Georgsson Öhman S, Frans Ö et al. Posttraumatic stress among women after induced abortion: a Swedish multi-centre cohort study. BMC Womens Health 2013;13:52 10.1186/1472-6874-13-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocca CH, Kimport K, Gould H et al. Women's emotions one week after receiving or being denied an abortion in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2013;45:122–31. 10.1363/4512213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gould H, Perrucci A, Barar R et al. Patient education and emotional support practices in abortion care facilities in the United States. Womens Health Issues 2012;22:e359–64. 10.1016/j.whi.2012.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Upadhyay UD, Weitz TA, Jones RK et al. Denial of abortion because of provider gestational age limits in the United States. Am J Public Health 2014;104:1687–94. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones RK, Zolna MR, Henshaw SK et al. Abortion in the United States: incidence and access to services, 2005. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2008;40:6–16. 10.1363/4000608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychia 2004;9:9–14. 10.1185/135525703125002360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pazol K, Zane S, Parker WY et al. , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Abortion surveillance—United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60:1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster DG, Steinberg JR, Roberts SC et al. A comparison of depression and anxiety symptom trajectories between women who had an abortion and women denied one. Psychol Med 2015;45:2073–82 10.1017/S0033291714003213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts SC, Biggs MA, Chibber KS et al. Risk of violence from the man involved in the pregnancy after receiving or being denied an abortion. BMC Med 2014;12:144 10.1186/s12916-014-0144-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biggs MA, Gould H, Foster DG. Understanding why women seek abortions in the US. BMC Womens Health 2013;13:29 10.1186/1472-6874-13-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data, 2nd edition. 2nd edn New York, NY: Wiley, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCulloch CE, Searle SR, Neuhaus JM. Generalized, linear, and mixed models, 2nd edition: Wiley, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones RK, Jerman J. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2011. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2014;46:3–14. 10.1363/46e0414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perrin M, Vandeleur CL, Castelao E et al. Determinants of the development of post-traumatic stress disorder, in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:447–57. 10.1007/s00127-013-0762-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:1048–60. 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daugirdaitė V, van den Akker O, Purewal S. Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic stress disorder after termination of pregnancy and reproductive loss: a systematic review. J Pregnancy 2015;2015:646345 10.1155/2015/646345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamama L, Rauch SA, Sperlich M et al. Previous experience of spontaneous or elective abortion and risk for posttraumatic stress and depression during subsequent pregnancy. Depress Anxiety 2010;27:699–707. 10.1002/da.20714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reese C, Pederson T, Avila S et al. Screening for traumatic stress among survivors of urban trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:462–7; discussion 67–8 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825ff713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cockrill K, Upadhyay UD, Turan J et al. The stigma of having an abortion: development of a scale and characteristics of women experiencing abortion stigma. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2013;45:79–88. 10.1363/4507913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shellenberg KM, Tsui AO. Correlates of perceived and internalized stigma among abortion patients in the USA: an exploration by race and Hispanic ethnicity. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;118(Suppl 2):S152–9. 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60015-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman PK, Coyle CT, Rue VM. Late-term elective abortion and susceptibility to posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Pregnancy 2010;2010:130519 10.1155/2010/130519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobkin LM, Gould H, Barar RE et al. Implementing a prospective study of women seeking abortion in the United States: understanding and overcoming barriers to recruitment. Womens Health Issues 2014;24:e115–23. 10.1016/j.whi.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]