Abstract

Purpose

We initiated the Genetics of Glucose regulation in Gestation and Growth (Gen3G) prospective cohort to increase our understanding of biological, environmental and genetic determinants of glucose regulation during pregnancy and their impact on fetal development.

Participants

Between January 2010 and June 2013, we invited pregnant women aged ≥18 years old who visited the blood sampling in pregnancy clinic in Sherbrooke for their first trimester clinical blood samples: 1034 women accepted to participate in our cohort study.

Findings to date

At first and second trimester, we collected demographics and lifestyle questionnaires, anthropometry measures (including fat and lean mass estimated using bioimpedance), blood pressure, and blood samples. At second trimester, women completed a full 75 g oral glucose tolerance test and we collected additional blood samples. At delivery, we collected cord blood and placenta samples; obstetrical and neonatal clinical data were abstracted from electronic medical records. We also collected buffy coats and extracted DNA from maternal and/or offspring samples (placenta and blood cells) to pursue genetic and epigenetic hypotheses. So far, we have found that low adiponectin and low vitamin D maternal levels in first trimester predict higher risk of developing gestational diabetes.

Future plans

We are now in the phase of prospective follow-up of mothers and offspring 3 and 5 years postdelivery to investigate the consequences of maternal dysglycaemia during pregnancy on offspring adiposity and metabolic profile.

Trial registration number

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, GENETICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Prospective design from early pregnancy enables detailed and standardised collection of anthropometric measures and lifestyle questionnaires to give information on most known potential confounders to glycaemic regulation impairments.

Our biobank contains both maternal and fetal blood and placenta samples.

Participants are highly representative of the general population of pregnant women receiving obstetric care at our institution.

As our population is mostly Caucasian, results may not be entirely generalisable to more diverse populations.

Introduction

Obesity and diabetes are major health problems recognised worldwide.1 Excess adiposity is the main risk factor for insulin resistance (IR), type 2 diabetes (T2D) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), all conditions that are associated with long-term cardiometabolic complications.2 3 The impact of impaired glucose regulation in pregnancy is especially worrisome because of associated short-term and long-term metabolic outcomes for both mothers4 5 and offspring.6–8 Exposure to GDM during fetal development increases risk of macrosomia, fetal hyperinsulinaemia and neonatal hypoglycaemia at birth, in addition to IR, metabolic syndrome and T2D over the child's lifetime.6–8 This long-term phenomenon is described as fetal programming.

The Genetics of Glucose regulation in Gestation and Growth (Gen3G) cohort aimed to increase our understanding of glucose regulation determinants in pregnancy and fetal growth with emphasis on interactions between genetics and environmental—or lifestyle—factors. We are especially interested in the roles of adipokines and vitamin D during pregnancy and in fetal development. By recruiting women at first trimester, we aimed to understand early pregnancy determinants implicated in the progressive gestational increase in IR and development of GDM. We are investigating genetic determinants of glucose regulation in pregnancy, so far based on hypothesis-driven candidate genes approaches, with the intent to use hypothesis-free approaches eventually. We are also interested in the consequences of maternal glycaemia and metabolic milieu alterations on epigenetic regulation in offspring energy and metabolic pathways.

Cohort description

Gen3G is a prospective observational cohort study. We recruited pregnant women representing the general population of women in reproductive age from the Eastern Townships region, in Québec, Canada.9 The work conducted for the prospective follow-up during pregnancy and collection of samples and data presented here was funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA), and Diabète Québec. Every participant gave written informed consent before enrolment in the study, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

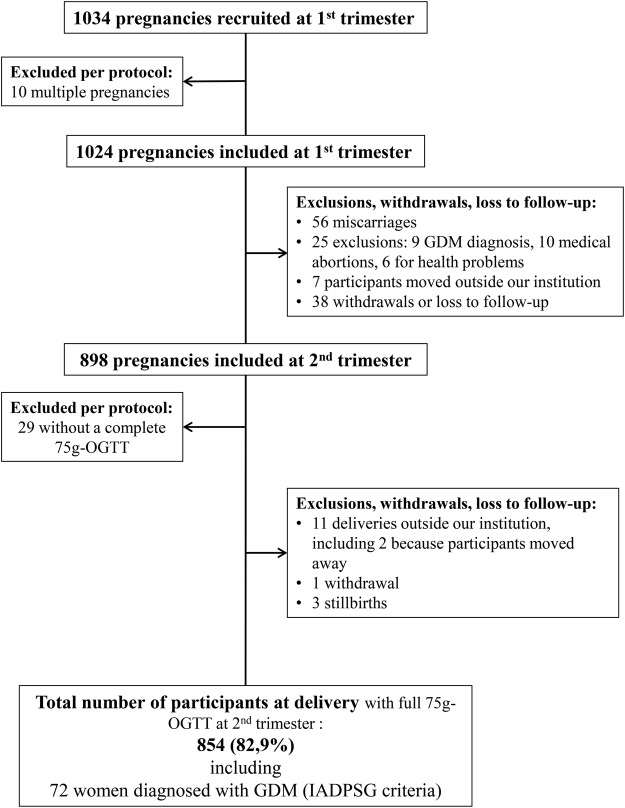

We recruited a total of 1034 pregnant women between January 2010 and June 2013 (see figure 1). All women were invited to participate if they received prenatal care directly at or in a health centre affiliated with the CHUS and planned delivery at the CHUS. The CHUS is the only hospital in the Eastern Township region offering obstetric care for deliveries; it provides care for about 2800 deliveries per year. Nursing staff invited women to participate during a routine prenatal visit to the CHUS Blood sampling in pregnancy clinic,9 all eligible women were invited with equal chance to participate in the study. If women were interested, research staff was contacted to describe the study and women could choose to contribute to different aims presented as substudies on adipokines, vitamin D and genetic determinants of gestational glucose regulation. Recruitment was eased because participation involved little additional burden to clinical requirements: drawing extra blood and answering questionnaires during visits that were clinically indicated at first and second trimesters, and collection of samples at delivery, all with minimal risk. If any woman was pregnant for a second time during the study timeline and wanted to participate again, the second index pregnancy was included separately and was identified with a distinct study identification number (31 women contributed 2 pregnancies during study).

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating the number of participants enrolled and active in the cohort from January 2010 to June 2013. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IADPSG, International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Compared with the general population of pregnant women receiving prenatal care and delivering at the CHUS, Gen3G participants showed similar demographic characteristics in terms of age, parity, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and ethnic background (table 1). Similar proportions of women with abnormal glucose tolerance were detected, and GDM screening was performed at the same time during second trimester. Based on this comparison, we feel confident that the cohort is representative of the population of pregnant women in our area.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Gen3G participants and of the general population of pregnant women who delivered at the CHUS over same time period

| Gen3G participants (n=1024*) |

CHUS patients, between 2008 and 2011 (n=7710) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N | Median [IQR] or N (%) | N | Median [IQR] or N (%) |

| Age (years) | 1024 | 28.0 [25.0–31.0] | 7507 | 28.0 [24.0–31.0] |

| European descent | 1012 | 964 (95.3) | 5224 | 4758 (91.1) |

| Primiparity | 1024 | 354 (34.6) | 8579† | 2849 (33.2) |

| Self-reported pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 1014 | 23.2 [20.9–27.3] | 7225 | 23.2 [20.9–26.7] |

| Abnormal glucose tolerance at first trimester‡ | 1024 | 9 (0.9) | 3047 | 56 (1.8) |

| GDM diagnosis at V2 | 5354 | 530 (9.9)§ | ||

| According to CDA¶ | 823 | 43 (5.2) | ||

| According to IADPSG | 823 | 80 (8.9) | ||

| Gestational week at which GDM screening was performed in the second trimester | 893 | 26.2 [25.6–27.1] | 5361 | 26.4 [26.0–28.0] |

2008 CDA criteria: 50 g glucose challenge followed by a 1 h plasma glucose. If 1 h plasma glucose <7.8, no GDM. If 1 h plasma glucose ≥10.3, GDM diagnosis. If 1 h plasma glucose is 7.8–10.2, reassess with a 75 g OGTT (fasting plasma glucose <5.3, 1 h plasma glucose <10.6, 2 h plasma glucose <8.9; if one value is exceeded, IGT diagnosis; if more than one value is exceeded, GDM diagnosis).

IADPSG criteria: 75 g OGTT with fasting, 1 and 2 h plasma glucose. If fasting plasma glucose ≥5.1 and/or 1 h plasma glucose ≥10.0 and/or 2 h plasma glucose ≥8.5, GDM is diagnosed.

*In total,1034 participants accepted inclusion in the study, but multiple pregnancies (n=10) were excluded from these analyses.

†Total number of pregnancies, completed or not, seen at least once at the CHUS between 2008 and 2011.

‡Abnormal glucose tolerance was defined as reaching a blood glucose level ≥10.3 mmol/L 1 h after the 50 g GCT.

§Determined by the per cent of women referred to our institution's Endocrinology in Pregnancy Clinic; not all women performed 75 g OGTT or performed it at our institution.

¶Including GDM and IGT diagnoses as per the 2008 CDA guidelines for glucose levels above threshold at one time point (IGT diagnosis) or two time points (GDM diagnosis) during the 75 g OGTT (three points: fasting, 1 and 2 h).

BMI, body mass index; CDA, Canadian Diabetes Association; CHUS, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; Gen3G, Genetics of Glucose regulation in Gestation and Growth; IADPSG, International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Study procedures

We collected data and samples at three time points during pregnancy (see figure 1). The first research visit (V1) was between 5 and 16 weeks of gestation, coinciding with women's first trimester prenatal clinical blood sampling as requested by their primary care physician. During this visit, we collected demographic data, medical history and anthropometric measurements; women completed questionnaires about lifestyle, and we collected extra blood samples during the clinically indicated blood draw (the majority during a 50 g glucose challenge test (GCT)). Most women performed this test as our cohort study happened in conjunction with a CDA-funded study (principal investigator: J-LA) investigating the value of a first trimester 50 g GCT in identifying women at risk of GDM later during pregnancy. Women were excluded (n=9) if they: had known pre-pregnancy diabetes, took medication that influenced glucose tolerance, had glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥6.5% or 1 h glucose ≥10.3 mmol/L post-50 g GCT, as this was classified as overt diabetes based on 2008 CDA criteria.10 Maternal glycaemia was kept blinded if results of glucose levels after the 50 g GCT were <10.3 mmol/L (per protocol of CDA-funded study).

The second visit (V2) was planned between 24 and 30 weeks, concomitantly with clinically indicated GDM screening test—in line with universal second trimester screening recommendations (both CDA and International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) guidelines).10 11 During V2, we updated medical history, repeated anthropometry measures, and women completed the same questionnaires about lifestyle. We collected extra blood samples at each point of the 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT; fasting, 1 and 2 h). Women diagnosed with GDM at that visit were followed up and treated according to 2008 CDA guidelines adopted at that time at our institution. Between V1 and V2, we excluded 81 (7.8%) women per protocol for miscarriage, medical abortions or health problems that prohibited participation (see figure 1). Another 45 (4.4%) participants moved away or declined further participation before V2.

At the end of pregnancy, we successfully collected clinical data from electronic hospital records for the majority of participants (82.9% of women recruited; 95.1% of women still active at V2). Information concerning 15 deliveries (1.7% of women still part of the study after V2) is missing or was excluded due to: delivery at another institution, active withdrawal or stillbirth. We collaborated with research in obstetric services (led by collaborator Dr J-C Pasquier) which offered trained research staff on call 24 h per day, 7 days per week and were directly contacted by clinical nurses from the obstetric department each time a study participant was admitted for delivery. These services were in place for multiple clinical research studies apart from Gen3G. Based on this unique set-up and in collaboration with researchers from the obstetric department, collection of biological samples for 736 (84.1%) deliveries was possible. Sample collection was missed for 147 deliveries (15.9%) for the following reasons: short time between participant admission and delivery, clinical staff omitted to contact research staff, communication issues (pager failure), coagulated cord blood before arrival of research staff, break in research staff services (holidays).

Table 2 shows characteristics of women recruited in Gen3G that were followed until delivery compared with women who were excluded, withdrawn or lost to follow-up. No significant demographic differences between groups were observed. Familial history of diabetes was slightly more common in women who remained in the study. The proportion of women with positive personal history of previous GDM or macrosomic offspring was not different between women who completed the study and those who did not.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of women recruited in Gen3G that were followed until delivery compared with women who were excluded, withdrawn or lost to follow-up

| Characteristics | Participants with delivery research data collected (n=854) | Participants lost to follow-up before or at delivery (n=170*) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or median [IQR] | |||

| Age (years) | 28.0 [25.0–31.0] | 28.0 [25.0–31.0] | 0.46 |

| Primiparity | 294 (34.4) | 60 (35.3) | 0.45 |

| Self-reported pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 [20.9–27.3] | 22.7 [20.9–27.5] | 0.49 |

| European descent | 814 (95.3) | 163 (90.6) | 0.11 |

| Positive family history of diabetes | 168 (19.7) | 22 (12.9) | 0.04 |

| Positive personal history of previous GDM or macrosomic newborn | 89 (10.4) | 18 (10.6) | 0.95 |

p Value was determined with χ2 test for categorical data (parity, ethnicity, history of diabetes/GDM/macrosomic newborn) and Mann-Whitney test for continuous, non-parametric data (age, BMI).

*Participants with multiple pregnancies, excluded shortly after inclusion per protocol, were not included in these analyses (n=10).

BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; Gen3G, Genetics of Glucose regulation in Gestation and Growth.

Data collection

Maternal anthropometry and vital signs (V1, V2)

Anthropometry was measured according to standardised procedures: weight (in kg) was measured with a calibrated electronic scale with bare feet in light clothing; height (in m) was measured with a wall stadiometer without shoes. BMI was calculated as weight divided by squared height (kg/m2). Body fat percentage (BFP) was estimated based on lean body mass measured by bioimpedance using a standing foot-to-foot scale (TBF-300A; Tanita. Coefficient of variation (CV): 2.1%12). Waist circumference (WC) was measured with a flexible measuring tape (in cm) above the top of the iliac crest; measurement was performed twice13 and the average was recorded. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured (in mm Hg) thrice in the sitting position after 5 min of rest; the average of these three measurements is used in analyses (see table 3 for a general overview of characteristics in participants and offspring).

Table 3.

Gen3G participant's characteristics during pregnancy and at birth

| Parameter | Total valid n* | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||

| Age (year) | 962 | 28.4±4.5 |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 962 | 918 (95.4) |

| Alcohol consumers (currently consuming) | 962 | 10 (1.0) |

| Alcohol consumption (portion per week) | 8 | 0.7 [0.2–7] |

| Smoking | 962 | |

| Past smokers | 365 (37.9) | |

| Current smokers | 104 (10.8) | |

| Cigarettes smoked per day (in current smokers only) | 6.5 [3.6–10.0] | |

| Parity (% primiparous) | 962 | 332 (34.5) |

| Medical diagnosis | 962 | |

| PCOS | 16 (1.7) | |

| Asthma | 63 (6.5) | |

| Allergies | 168 (17.5) | |

| Gastric reflux | 61 (6.3) | |

| Thyroid problems | 104 (10.8) | |

| Bladder problems | 20 (2.1) | |

| Mental health issues | 46 (4.8) | |

| Pre-pregnancy weight† (kg) | 952 | 63.5 [56.8–74.8] |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 952 | 23.3 [20.9–27.4] |

| Visit 1 | ||

| Gestational week | 962 | 9.6±2.3 |

| Season of visit (% women recruited at) | 961 | Summer:24%; Fall:23% Winter:23%; Spring:30% |

| Sun exposure† | 943 | |

| High | 645 (68.4) | |

| Medium | 284 (30.1) | |

| Low | 14 (1.5) | |

| Nutrition | ||

| Fruits and vegetables (times per day) | 777 | 5 [4–7] |

| Breakfast consumption | 947 | |

| Every day or most days | 886 (93.6) | |

| Less than most days | 61 (6.4) | |

| Restaurant meals (times per month) | 923 | 4 [2–8] |

| Fish consumption (>2 per week) | 955 | 150 (15.7) |

| Physical activity | ||

| Energy spent (kcal/kg/day) | 861 | 1.48 [0.70–2.65] |

| Sleep duration (hours per night) | 861 | 8.3±1.3 |

| Sedentary activities (hours per week) | 857 | 15.7±8.8 |

| Anthropometry | ||

| Weight (kg) | 962 | 65.4 [58.5–77.9] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 962 | 24.2 [21.6–28.2] |

| Body fat (%) | 957 | 32.0±8.5 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 962 | 90 [82.0–99.0] |

| Systolic/diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 960 | 110/69±10/7 |

| Blood biochemistry | ||

| Glycaemic regulation | ||

| Glycaemia post-50 g GCT (mmol/L) | 913 | 5.4 [4.6–6.5] |

| Side effects due to the 50 g GCT (% yes) | 962 | 288 (29.9) |

| HbA1c (%) | 956 | 5.2±0.3 |

| Apo B (mmol/L) | 399 | 0.78±0.19 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 960 | 2.23±0.10 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/L) | 958 | 1.03±0.16 |

| Parathormone (pmol/L) | 999 | 2.3 [1.8–3.0] |

| Vitamin D [25OHD2 and D3] (nmol/L) | 790 | 63.4±19.6 |

| Adiponectin (µg/mL) | 479 | 11.8±4.6 |

| Peptide C (pg/mL) | 814 | 1826 [1436–2390] |

| Insulin (pg/mL) | 814 | 1287 [898–1817] |

| Leptin (pg/mL) | 814 | 8467 [4685–13 806] |

| TNFα (pg/mL) | 814 | 1.58 [1.20–2.12] |

| Visit 2 | ||

| Gestational week | 857 | 26.4±1.0 |

| Season of visit (% women with visit 2 at) | 851 | Summer:33%; Fall:24% Winter:24%; Spring:19% |

| Sun exposure† | 847 | |

| High | 550 (64.9) | |

| Medium | 256 (30.2) | |

| Low | 48 (5.7) | |

| Nutrition | ||

| Fruits and vegetables consumption (times per day) | 824 | 6 [5–8] |

| Breakfast consumption | 843 | |

| Every day or most days | 829 (98.3) | |

| Less than most days | 21 (1.7) | |

| Restaurant meals (times per month) | 843 | 4 [2–8] |

| Fish consumption (>2 per week) | 850 | 131 (15.4) |

| Physical activity | ||

| Energy spent per day (kcal/kg) | 849 | 1.24 [0.52–2.24] |

| Sleep duration (hours per night) | 839 | 8.1±1.4 |

| Sedentary activities (hours per week) | 834 | 17.1±10.1 |

| Anthropometry | ||

| Weight (kg) | 854 | 72.5 [66.0–83.9] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 854 | 26.8 [24.2–30.4] |

| Body fat (%) | 846 | 35.9±6.7 |

| Systolic/diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 851 | 107/67±9/7 |

| Blood biochemistry | ||

| Glycaemic regulation | ||

| Fasting glycaemia (mmol/L) | 854 | 4.2 [4.0–4.4] |

| Glycaemia 1 h into OGTT | 854 | 7.1 [6.0–8.1] |

| Glycaemia 2 h into OGTT | 854 | 5.7 [4.9–6.7] |

| Side effects due to the 75 g OGTT (% yes) | 848 | 395 (46.6) |

| HbA1c (%) | 854 | 5.0 [4.8–5.2] |

| GDM diagnosis | 854 | 72‡ (8.4) |

| Lipid profile | ||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 853 | 6.20±1.11 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 853 | 1.92±0.63 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 824 | 1.92±0.42 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 818 | 3.46±1.00 |

| Apo A (mmol/L) | 851 | 2.11±0.28 |

| Apo B (mmol/L) | 851 | 1.21±0.28 |

| Fasting NEFA (nmol/L) | 260 | 0.25±0.10 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 835 | 2.08±0.12 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/L) | 834 | 0.83±0.12 |

| Parathormone (pmol/L) | 833 | 2.7 [2.2–3.4] |

| Fasting adiponectin (µg/mL) | 843 | 12.5±4.7 |

| Fasting peptide C (pg/mL) | 820 | 844 [630–1169] |

| Fasting insulin (pg/mL) | 795 | 293 [213–412] |

| Fasting leptin (pg/mL) | 824 | 14 093 [8668–22 145] |

| Fasting TNFα (pg/mL) | 825 | 1.62 [1.18–2.19] |

| Delivery | ||

| Gestational week§ | 844 | 39.3±1.4 |

| End-of-pregnancy weight§¶ | 841 | 78.2 [71.3–90.0] |

| GDM treatment§ | 80 | |

| Not referred to CHUS GDM clinic | 24 (30.0) | |

| Lifestyle | 19 (23.8) | |

| Lifestyle+pharmacological treatment | 37 (46.3) | |

| Use of antibiotics before/during delivery§ | 807 | 301 (37.3) |

| Anaesthesia (any kind)§ | 813 | 742 (91.3) |

| Delivery mode§ | 854 | |

| Caesarean section (first time) | 77 (9.0) | |

| Caesarean section (iterative) | 65 (7.6) | |

| Vaginal | 712 (83.4) | |

| Newborns characteristics | ||

| Sex (% female)§ | 854 | 410 (48.0) |

| APGAR score at 1 min§ | 854 | 9 [8–9] |

| APGAR score at 5 min§ | 854 | 9 [9–10] |

| Breastfeeding status at discharge§ | 739 | |

| Breastmilk only | 670 (90.7) | |

| Artificial only | 62 (8.4) | |

| Mixed | 7 (0.9) | |

| Malformation§ | 853 | 12 (1.4) |

| Admission to NICU§ | 805 | 81 (10.1) |

| Hypoglycaemia at birth§ | 807 | 94 (11.6) |

| Hyperbilirubinaemia§ | 819 | 104 (12.7) |

| Fracture or dislocation§ | 806 | 9 (1.1) |

| Anthropometry | ||

| Birth weight (kg)§ | 851 | 3.405 [3.115–3.705] |

| Birth weight z-score** | 851 | 0.06±0.87 |

| Weight for gestational age** | 851 | |

| Small | 36 (4.2) | |

| Adequate | 752 (88.4) | |

| Large | 63 (7.4) | |

| Body fat mass (kg)†† | 262 | 0.57±0.16 |

| Body fat percentage | 262 | 16.5±3.1 |

| Birth length (cm)§ | 853 | 50.9±2.3 |

| Birth length z-score¶ | 846 | 0.32±0.82 |

| Head circumference (cm)§ | 848 | 34.5±1.5 |

| Head circumference z-score** | 848 | 0.04±0.95 |

| Cord blood biochemistry | ||

| Vitamin D [25OHD2 and D3] (nmol/L) | 655 | 52.8±18.2 |

| Adiponectin (µg/mL) | 644 | 24.3±10.8 |

| Peptide C (pg/mL) | 650 | 413 [313–605] |

| Insulin (pg/mL) | 655 | 315 [236–431] |

| Leptin (pg/mL) | 658 | 11 593 [5842–19 494 ] |

| TNFα (pg/mL) | 660 | 5.37 [4.13–6.86] |

| pH§ | 830 | 7.24±0.22 |

| pCO2 (mm Hg)§ | 818 | 53.9 [47.1–61.4] |

| pO2 (mm Hg)§ | 813 | 22.5 [17.6–27.8] |

| HCO3 (mmol/L)§ | 818 | 23.3 [21.5–25.0] |

| Haemoglobin (g/L)§ | 851 | 157 [146–168] |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 660 | 4.44±0.93 |

*This n indicates the maximum number of participants that contributed data for a specific variable at a specific time point.

†Self-reported.

‡Eight additional participants were diagnosed with GDM through other modes than IADPSG criteria before the research visit 2 and thus did not undergo a full OGTT.

§Starred variables were extracted from electronic hospital records.

¶Weight at the last routine visit before delivery, taken from the medical chart. The gestational week at which that measure was taken varies.

**Fenton's chart16 was used to calculate z-scores and weight for gestational age.

††Calculated from measured skinfold thickness (tricep, bicep, subscapulla and suprailiac folds).

Apo A, apolipoprotein A; Apo B, apolipoprotein B; BMI, body mass index; CHUS, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; Gen3G, Genetics of Glucose regulation in Gestation and Growth; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HCO3, bicarbonate concentration; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IADPSG, International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NEFA, non-esterified fatty acids; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; pCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; pH, acidity; pO2, partial pressure of oxygen; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Neonatal anthropometry (delivery)

Weight (in g) and length (in cm) of newborns were measured following standard clinical procedures, with an electronic scale and a measuring tape by obstetrics nurses within 2 h of delivery. We collected these and other relevant clinical information available in electronic medical records (detailed in box 1). In January 2012, neonate skinfolds thickness (SFT) measurements were added to the protocol. We measured triceps, biceps, subscapular and suprailiac skinfolds (in mm) in duplicate on the right side of neonates. Trained research staff measured SFT following a standard procedure14 with a calibrated skinfold caliper (AMG Medical). Triceps SFT was taken parallel to the long axis, midway between the acromial and the olecranon with the arm slightly flexed. Biceps SFT was measured at the middle point on the front of the slightly extended arm. Subscapular SFT was taken 1–2 cm below the lower tip of the scapula and suprailiac SFT was taken on the natural fold of the skin just above the iliac crest. Measures were recorded when the most constant reading was read on the caliper (considering neonate's movements). Triplicate measurement was taken if duplicate varied over 10.0%. We successfully measured SFT in a total of 265 newborns (31.0% of total deliveries, 67.3% of deliveries after initiation of SFT measurements in our research protocol). SFT are missing in cases where mothers did not give verbal consent following delivery, neonates were receiving care in the neonatology unit, or mothers and newborns were discharged home before trained research staff could measure SFT. Two trained research staff repeated SFT measures on the same 40 newborns (15.0%); interindividual variability was 1.5%.

Box 1. Data collected from staff-administered questionnaires and/or electronic medical data records.

V1 (n=1024)

Date and season of visit

Age

Date of last menses, planned delivery date, estimated gestational week

Blood group

Alcohol and tobacco use (never, prior and cessation date, or current and daily consumption)

Medication in use at the time of the visit (including natural products, vitamin and mineral supplementation)

Side effects of the glucose challenge test (when applicable)

Parity (live births, stillbirths, abortions)

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) risk factors (according to Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA) and American Diabetes Association (ADA))

Personal and familial medical history

Marital status, type of employment

Hour of last food intake, hour of the day at which glucose challenge test was administered

Sun exposure questionnaire (typical, trips, tanning)

Diet (summary fish and milk consumption, weekly fruits and vegetables consumption, breakfast habits, restaurant visits)

Physical activities:

Commuting and daily living (including type of commuting, choice of stairs vs elevator)

Last 3 months of leisure physical activities (derived from Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) questionnaire,15 metabolic equivalent of tasks (METs) estimation)

Daily sleep time

Weekly work hours

Weekly sedentary recreational activities time accorded to: computer, video game, television and reading

V2 (n=854)

Date and season of visit

Updated medication (including natural products, vitamin and mineral supplementation)

Updated medical conditions

Blood group (confirmed)

Oral glucose tolerance test's side effects

Sun exposure (usual, trips, tanning)

Summary fish and milk consumption

Diet (summary fish and milk consumption, weekly fruits and vegetables consumption, breakfast habits, restaurant visits)

Physical activities:

Commuting and daily living (including type of commuting, choice of stairs vs elevator)

Last 3 months of leisure physical activities (derived from CCHS questionnaires15, METs estimation)

Daily sleep time

Weekly work hours

Weekly sedentary recreational activities time accorded to: computer, video game, television and reading

Delivery: obstetric data abstracted from medical records (n=862)

Gestational age at delivery

Diagnostics at delivery (GDM: type of treatment; other pregnancy complications)

Labor details (spontaneous or induction, length of labour, analgesia, steroids, antibiotics, anaesthesia)

Delivery date and time, type (natural, caesarean)

Episiotomy, laceration (perineal, vaginal), approximate blood loss, amniotic fluid description, umbilical cord description

Delivery: neonate data abstracted from medical records (n=854)

Sex of neonate

Alive/dead status, resuscitation (type of air feed), transfer to neonatal intensive care unit

APGAR scores (1 and 5 min)

First and second or third trimesters echography details (when performed)

Neonatal clinical evaluation recorded in electronic medical records: malformations, head symmetry, skin colouration, consciousness level

Total birth length, head circumference

Feeding during hospitalisation and intent (maternal breast feeding/formula)

Length of stay for hospitalisation following delivery (excluding subsequent visits after discharge)

Neonatal complications (during hospitalisation postdelivery): neonatology unit care, bradycardia, respiratory problems, hypoglycaemia, hypocalcaemia, hyperbilirubinaemia, polycythaemia, fractures/dislocations, intensive care stay, respiratory therapy, others

Placental weight

Medical history (V1, V2, delivery)

Trained research staff administered standardised questionnaires during study visits to determine participants’ medical history. Clinical data regarding any late pregnancy medical updates, perinatal events, delivery details and neonate health parameters at birth were abstracted from electronic health records. Full list of data collected is detailed in box 1.

Lifestyle questionnaires (V1, V2)

Trained research staff administered standardised questionnaires15 at both visits to collect details on diet (food type and frequency), sun exposure, and physical and sedentary activities. Full list of data collected is detailed in box 1.

Maternal blood samples (V1, V2)

At V1, extra blood was collected to obtain plasma and buffy coat 1 h after the 50 g GCT, for storage (for planned DNA extraction). At V2, we collected extra blood samples at fasting, 1 and 2 h over the course of the 75 g OGTT to store plasma and buffy coat, at the same time of clinically indicated blood draws for GDM diagnosis (see table 4).

Table 4.

Biological samples of Gen3G mothers and offspring

| Time point | Sample type (additive) | Maximum number of aliquots | Number of participants that accepted biobanking |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1 First trimester after 50 g GCT or non-fasting (2010–2013) |

Plasma (EDTA) | 8 | 996 |

| Buffy coat (EDTA) | 1 | 962 | |

| V2 Second trimester during 75 g OGTT (2010–2013) |

Plasma T0—fasting (EDTA) | 8 | 843 |

| Plasma T1 h (EDTA) | 8 | ||

| Plasma at T2 h (EDTA) | 8 | ||

| Buffy coat T0 (EDTA) | 1 | 821 | |

| Buffy coat T2 h (EDTA) | 1 | ||

| Delivery (2010–2014) | Plasma (EDTA) | 16 | 662 |

| Serum (SST) | 4 | 552 | |

| Whole cord blood (NaF, EDTA) | 4 | 403 | |

| Buffy coat (EDTA) | 3 | 640 | |

| RNA PAXgene* | – | 597 | |

| Placenta, fetal side (RNA Later) | – | 694 | |

| Placenta, maternal side (RNA Later) | – |

Additives: RNA Later, ammonium sulfate; SST, coagulation activator and serum separator; NaF, fluoride sodium.

Data were compiled and accurate on 12 May 2014.

Biobank: denominised data and samples accessible for projects related to other pregnancy-related conditions.

*RNA PAXgene additive induces cell lysis, stabilises RNA and reduces RNA degradation and gene transcription. This tube was not aliquoted.

GCT, glucose challenge test; Gen3G, Genetics of Glucose regulation in Gestation and Growth; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; T0, samples taken under fast; T1 h, samples taken 1 h after the start of the 75 g OGTT; T2 h, samples taken 2 h after the start of the 75 g OGTT.

Placenta and cord blood samples

At delivery, we collected cord blood for serum, plasma, buffy coat, whole blood and RNA (in PAXgene tubes). One cm3 of maternal and fetal placenta tissue was collected approximately 5 cm from the cord immediately after observation by the obstetrician. These samples were preserved in RNA Later (Qiagen) as indicated by the manufacturer and kept at −80°C for later RNA extraction (see table 4).

Handling of biological specimen

To inhibit protein degradation, aprotinin (1 µL/mL of blood) was added to each blood sample (V1, V2, cord blood) before centrifugation at 2500g for 10 min at 4°C. Plasma, serum, whole blood and buffy coats were aliquoted (300–500 µL/aliquot), wrapped in paraffin paper to avoid evaporation, and stored at −80°C. All participants consented to additional analyses, related to our original research questions, using their own and their offspring samples; most also consented to donate any remaining samples to our anonymised biobank (n=996). Maximum numbers of samples collected per type of sample are listed in table 4.

Biomarkers measurement

The CHUS biomedical laboratory performed the following biochemical measurements on fresh samples (time points listed in table 5): plasma glucose (by the glucose hexokinase method; Roche Diagnostics), fasting total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and triglycerides (by colorimetric methods; Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels (calculated using Friedewald's equation), HbA1c (by HPLC; Bio-Rad VARIANT), calcium (by colorimetric assay), parathormone (by electrochemiluminescent assay) and phosphorus (by photometry) as previously described.17 Vitamin D (25OHD2 and 25OHD3) levels were measured in a biochemistry research laboratory (led by collaborator Dr G Fink) at our institution by liquid–liquid extraction followed by liquid chromatography/electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (Quattro micro mass spectrometer; Waters).18 The sum of 25OHD2 and 25OHD3 levels was considered total plasma 25OHD levels. Minimum detectable concentration (MDC) was 1.25 nmol/L for 25OHD2 and 6.25 nmol/L for 25OHD3. Intra-assay and interassay CVs were, respectively, 7.4% and 4.1% for 25OHD2 and 4.7% and 2.9% for 25OHD3.

Table 5.

Number of clinical and biochemical measures available at each Gen3G research visit

| V1 5–16 weeks of gestation Maximum N=1024 |

V2 24–28 weeks of gestation Maximum N=898 |

Delivery 29–42 weeks of gestation Maximum N=854 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric measures and vital signs | |||

| Pregestational weight | 1024* | – | – |

| Height | 1024 | – | – |

| Weight | 1024 | 882 | 854* |

| Bioimpedance | 1017 | 865 | – |

| Waist circumference | 1001 | – | – |

| Blood pressure | 1022 | 880 | – |

| Birth weight | – | – | 854* |

| Neonate skinfold thickness | – | – | 265 |

| Biochemical measures | |||

| Insulin, C peptide, leptin, TNFα | 814 | ∼810 per time point during OGTT | 658 in cord blood |

| Total adiponectin | 479 | 851 | 645 in cord blood |

| Vitamin D (25OHD) | 797 | – | 661 in cord blood |

| Plasma glucose | 970 | ∼860 per time point during OGTT | 665 in cord blood |

| Calcium | 1017 | 810 | – |

| Phosphate | 1015 | 809 | – |

| Parathyroid hormone | 997 | 807 | – |

| Total cholesterol | – | 867 | – |

| Triglycerides | – | 867 | – |

| HDL-cholesterol | – | 838 | – |

| LDL-cholesterol | – | 832 | – |

| Apo A | – | 863 | – |

| Apo B | 997 | 863 | – |

| HbA1c | 1015 | 865 | – |

| Cord blood pO2 | – | – | 812* |

| Cord blood pCO2 | – | – | 817* |

| Cord blood HCO3 | – | – | 817* |

| Cord blood pH | – | – | 819* |

*Pregestational weight was self-reported. Other starred variables were extracted from electronic hospital records.

Apo A, apolipoprotein A; Apo B, apolipoprotein B; Gen3G, Genetics of Glucose regulation in Gestation and Growth; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HCO3, bicarbonate concentration; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; pCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pH, acidity; pO2, partial pressure of oxygen; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

We performed the following biomarker measurements in our common endocrinology research laboratory (see table 5 for timing and number of samples analysed to date):

Cord blood glucose was measured by the glucose hexokinase method (Roche Diagnostics). MDC was 2.5 mM. Intra-assay and interassay CVs were 0.19% and 1.84%.

Total adiponectin levels were measured by radioimmunoassay (EMD Millipore). MDC was 0.78 ng/mL. Intra-assay and inter-assay CVs were both <10%.

Insulin, leptin, C peptide and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α concentrations were measured using a multiplexed particle-based flow cytometric assay (Human Milliplex map kits, EMD Millipore). MDC and lowest curve standard were, respectively, 87 and 45.7 pg/mL for insulin, 41 and 45.7 pg/mL for leptin, 9.5 and 22.9 pg/mL for C peptide, and 0.30 and 0.90 pg/mL for TNFα. Intra-assay and inter-assay CVs were, respectively, <10% and <15% for all analytes.

Plasma glucose and insulin values, either under fast or during the 75 g OGTT, were used to calculate the homoeostasis model of assessment of IR (HOMA-IR) as well as dynamic indices of insulin sensitivity and secretion: the Matsuda index (validated in pregnancy19), the total area under the curve of insulin divided by the total area under the curve of glucose (AUCinsulin/glucose), and insulin secretion-sensitivity index (ISSI)-2 according to published methods.11 19–21

Power calculation

Gen3G was planned to recruit over 1000 pregnant women to have adequate power to investigate biomarkers associated with risk of developing GDM and related to impaired glucose regulation in pregnancy. For example, we calculated that we would have 85% power to detect an OR=1.32 increased risk of GDM for each 1 µg/mL reduction of adiponectin (two-sided α 0.05). For genetic analyses, we based our power calculation on candidate genes that were previously shown to influence glycaemic traits in non-pregnant populations: depending on the region and number of single nucleotide polymorphisms tested, we estimated that we would have 80% power to explain between 1.0% and 1.8% of variance of glycaemic-related traits (using continuous measures). We were well aware that we did not have the sample size to conduct genome-wide analyses, but that our sample size and richness of phenotypes would allow us to contribute data to meta-analyses involving multiple cohorts.

Findings to date

Gen3G completed its recruitment in June 2013 and its follow-up until last delivery in February 2014. Accordingly, major published findings at the time of publication of this manuscript are summarised below.

Evaluating adiponectin and the risk of developing GDM

We investigated the role of adiponectin in glucose regulation during pregnancy and the risk of developing GDM22 as defined by IADPSG criteria. We demonstrated that women who developed GDM had lower first trimester adiponectin levels (9.67±3.84 vs 11.92±4.59 µg/mL; p=0.004) when compared with women who remained normoglycaemic. Lower adiponectin levels were associated with a higher risk of developing GDM (OR=1.14 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.25) per 1 µg/mL decrease in adiponectin levels; crude p=0.004) independent of adiposity (BMI, BFP or WC) and glycaemic regulation (HbA1c or glycaemia post-50 g GCT) at first trimester (OR=1.12 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.23); p=0.02 in fully adjusted models). Lower adiponectin levels at first and second trimesters were also associated with higher second trimester IR represented by HOMA-IR (both: r=−0.22, p<0.0001) and Matsuda index (respectively, r=0.28 and r=0.29, p<0.0001 for both), independent of age and BMI.

Understanding the role of TNFα in glucose regulation and IR in pregnancy

The role of TNFα in pregnancy-related IR has been examined20 23–25 but studies reported conflicting findings. We investigated the association between TNFα levels at first and second trimesters and IR in 756 women from Gen3G, taking into account confounding factors such as adiposity and other IR biomarkers. Our results show that higher maternal circulating TNFα levels were associated with higher IR as assessed by various indices (HOMA-IR: r=0.37, Matsuda: r=−0.30; p<0.0001 for both), independently from age, BMI, triglycerides and adiponectin levels.26 Interestingly, we detailed for the first time the dynamic response of circulating TNFα over the course of a 75 g OGTT in pregnant women. This study shows that at second trimester, TNFα levels dynamics varied differently in women categorised with elevated IR compared with women categorised with the lowest IR.

Assessing circulating vitamin D as a predictor of GDM

Among other biomarkers of interest, we investigated maternal vitamin D circulating levels at first trimester in relation with glycaemic regulation at second trimester and the risk of developing GDM. We demonstrated that lower first trimester 25OHD levels were associated with higher risk of developing GDM (OR=1.48 per SD decrease in 25OHD levels; p=0.04) within model adjusted for vitamin D-related confounding factors (such as season of sampling, parathormone levels and a vitamin D lifestyle score that included dietary intake and sunlight exposure) and known GDM risk factors (history of GDM or macrosomic newborn, maternal age, familial history of diabetes, ethnic background, parity and WC).27 Lower first trimester 25OHD levels were also associated with a higher index of IR (HOMA-IR; r=−0.08; p=0.03), a lower Matsuda index (r=0.13; p=0.001) and a lower ISSI-2 (r=0.08; p=0.04) assessed at second trimester.

Strengths and limitations

One of the Gen3G cohort's main strength is its prospective design from early pregnancy to delivery. The large sample size and population-based design allow inferring results to the general population of pregnant women in our region, but also to other populations who are mainly of European descent. We conducted detailed and standardised anthropometric measurements and lifestyle questionnaires that allow us to take into account most known potential confounders to glycaemic regulation impairments. We collected maternal blood samples at multiple time points of pregnancy and we successfully obtained cord blood and/or placenta in about 80% of deliveries. Placenta material in particular is a feature that few mother–child cohorts have. This opens the possibility of investigating epigenetics and gene expression (RNA and/or protein) specific to the role of placenta in health and diseases related to pregnancy. Gen3G sample size and collection of DNA on both mother and offspring also allow sufficient power to perform genetic association studies, for candidate genes approaches if considering Gen3G sample size alone, or as a decent additional cohort to contribute to meta-analyses. Integration of both genetics and epigenetics in our study is particularly attractive for questions related to the developmental origin of health and disease field. Of note, follow-up of mothers and children at 3 and 5 years old is ongoing. Visits include questionnaires, measures of anthropometry and collection of biological samples for genetic analyses and measures of biomarkers related to adiposity and glycaemia in both mothers and children. One other major strength resides in the vision the investigators invested in this cohort. Biological samples were collected, aliquoted and stored for future research questions and hypotheses related either to glycaemic regulation or other disorders of pregnancy (biobank, maximum n=996).

Limitations include the absence of fasting blood samples at first trimester, which would have allowed calculation of the IR index HOMA-IR early in pregnancy. Moreover, some biomarkers measured at first trimester are more sensitive to fasting status (eg, leptin and TNFα); not being able to measure their fasted levels at first trimester might have influenced our interpretation of change over the course of pregnancy. Fasting samples would also have been particularly useful for measurement of potential biomarkers that are highly sensitive to food intake, such as lipid, carbohydrates and amino acids metabolites that are now part of the upcoming field of metabolomics; however, emerging literature suggests that postglucose load metabolomics might be highly informative for investigations of weight and glycaemic-related traits.28–30 In addition, as the Eastern Townships population is mostly of European descent, our homogenous cohort population prevents generalisation of our results to populations with other ethnic background (Asian, Hispanic, Indigenous, African), who usually have a higher risk of GDM compared with women of European descent.

In hindsight, our data would have been enriched by adding a research visit during third trimester, for which we relied on medical records to collect end-of-pregnancy data that are not as reliable as standardised research assessments. Similarly, collection of paternal data and samples would have increased our ability to take into account familial factors and investigate parent-of-origin effect in our genetic studies. Also, emerging interests in microbiota and its relation to metabolism in pregnancy and offspring also lead us to believe that collecting stool, urine and amniotic fluid samples would have been of great value in our cohort. However, our choices of balancing ease of recruitment, participants’ burden and additional procedures, were to limit attrition—which was consequently relatively small compared with similar studies.31 32

Future plans

We are now in the phase of prospective follow-up of mothers and offspring 3 and 5 years postdelivery to investigate the consequences of maternal dysglycaemia during pregnancy on offspring adiposity and metabolic profile. We are seeking funding to enrich phenotypic characterisation and additional samples collection for epigenetic and biomarkers studies. We hope to continue to follow-up Gen3G participants over many years to come, if we have adequate funding and support.

Collaboration

Collaboration propositions are welcome, either in the form of accessing questionnaire-based data and/or biological samples. Investigators interested in GDM or other disorders of pregnancy can propose their ideas to have access to data/samples stored in our biobank. To discuss collaboration possibilities, investigators are invited to contact M-FH and PP (mhivert@partners.org; patrice.perron@usherbrooke.ca).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the blood sampling in pregnancy clinic at the CHUS and Sun Life Financial (which support research activities integrated to this clinic); the assistance of clinical research nurses (M Gérard, G Proulx, S Hayes, and M-J Gosselin) and research assistants (C Rousseau and P Brassard) for recruiting women and obtaining consent for the study; and the CHUS biomedical laboratory for performing assays. They also thank the Research in obstetrics services, led by collaborator Dr J-C Pasquier for their help in collecting samples at delivery, and Dr G Fink for facilitating all of our measures of vitamin D.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Jean-Charles Pasquier; Guy Fink.

Contributors: LG drafted the manuscript, performed descriptive data analysis and interpreted data, helped recruit participants and contributed to data collection and cleaning. CA, ML and JP contributed to data collection, analysis and interpretation, and reviewed the manuscript. M-CB, MD, JMo, and JMé contributed to participant recruitment, data collection, study coordination, and reviewed the manuscript. LB, J-LA, and PP participated in the study conception and design, contributed funding for data collection and analysis. M-FH conceived the study, participated in the study design, contributed funding for data collection and analysis, and helped draft the manuscript. All co-authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a Fonds de recherche du Québec en santé (FRQ-S) operating grant (to M-FH, grant #20697); a Canadian Institute of Health Reseach (CIHR) Operating grant (to M-FH grant #MOP 115071); a Diabète Québec grant (to PP) and a Canadian Diabetes Association operating grant (to J-LA, grant #OG-3-08-2622-JA). LB is a junior research scholar from the FRQ-S and a member of the FRQ-S-funded Centre de recherche du CHUS. M-FH was a FRQ-S Junior 1 research scholar and received a Clinical Scientist Award by the Canadian Diabetes Association and the Maud Menten Award from the CIHR-Institute of Genetics. J-LA is a FRQ-S Junior 2 research scholar. Analyses were supported by Diabète Québec internship awards (to LG, ML, JP), CIHR Master's training award (#299295 to CA), and FRQ-S Master's (#27029 to LG; #27113 to CA; #29033 to JP) and Doctoral training award (#27499 to ML).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: CHUS Ethics Review Board for Studies with Humans.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Anonymised data may be obtained by contacting M-FH and PP (mhivert@partners.org; patrice.perron@usherbrooke.ca) with a research question concerning GDM or pregnancy-related disorders.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Jean-Charles Pasquier and Guy Fink

References

- 1.Brownell KD, Yach D, Stuckler D. Epidemiologic and economic consequences of the global epidemics of obesity and diabetes. Nat Med 2006;12:62–6. 10.1038/nm0106-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Lorenzo A, Bianchi A, Maroni P et al. Adiposity rather than BMI determines metabolic risk. Int J Cardiol 2013;166:111 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neeland IJ, Turer AT, Ayers CR et al. Dysfunctional adiposity and the risk of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in obese adults. JAMA 2012;308:1150–9. 10.1001/2012.jama.11132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feig DS, Zinman B, Wang X et al. Risk of development of diabetes mellitus after diagnosis of gestational diabetes. CMAJ 2008;179:229–34. 10.1503/cmaj.080012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1862–8. 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang RC, de Klerk NH, Smith A et al. Lifecourse childhood adiposity trajectories associated with adolescent insulin resistance. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1019–25. 10.2337/dc10-1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1339–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa0902430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R et al. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 2005;115:e290–6. 10.1542/peds.2004-1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hivert MF, Allard C, Menard J et al. Impact of the creation of a specialized clinic for prenatal blood sampling and follow-up care in pregnant women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34:236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Diabetes A. Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada. 2008;32(Supp 1):S171–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33:676–82. 10.2337/dc09-1848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunez C, Gallagher D, Visser M et al. Bioimpedance analysis: evaluation of leg-to-leg system based on pressure contact footpad electrodes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997;29:524–31. 10.1097/00005768-199704000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Abridged edn Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmelzle HR, Fusch C. Body fat in neonates and young infants: validation of skinfold thickness versus dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:1096–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statistics Canada HC. Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes. Cycle 2.2. Nutrition (2004): sécurité alimentaire liée au revenu dans les ménages canadiens. Ottawa, ON: Bureau de la politique et de la promotion de la nutrition, Santé Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenton TR, Kim JH. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:59 10.1186/1471-2431-13-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gagnon C, Baillargeon JP, Desmarais G et al. Prevalence and predictors of vitamin D insufficiency in women of reproductive age living in northern latitude. Eur J Endocrinol 2010;163:819–24. 10.1530/EJE-10-0441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aronov PA, Hall LM, Dettmer K et al. Metabolic profiling of major vitamin D metabolites using Diels-Alder derivatization and ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem 2008;391:1917–30. 10.1007/s00216-008-2095-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirwan JP, Huston-Presley L, Kalhan SC et al. Clinically useful estimates of insulin sensitivity during pregnancy: validation studies in women with normal glucose tolerance and gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1602–7. 10.2337/diacare.24.9.1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIntyre HD, Chang AM, Callaway LK et al. Hormonal and metabolic factors associated with variations in insulin sensitivity in human pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33:356–60. 10.2337/dc09-1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1462–70. 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacroix M, Battista MC, Doyon M et al. Lower adiponectin levels at first trimester of pregnancy are associated with increased insulin resistance and higher risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1577–83. 10.2337/dc12-1731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirwan JP, Hauguel-De Mouzon S, Lepercq J et al. TNF-alpha is a predictor of insulin resistance in human pregnancy. Diabetes 2002;51:2207–13. 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jahromi AS, Zareian P, Madani A. Association of insulin resistance with serum interleukin-6 and TNF-alpha levels during normal pregnancy. Biomark Insights 2011;6:1–6. 10.4137/BMI.S6150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLachlan KA, O'Neal D, Jenkins A et al. Do adiponectin, TNFalpha, leptin and CRP relate to insulin resistance in pregnancy? Studies in women with and without gestational diabetes, during and after pregnancy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2006;22:131–8. 10.1002/dmrr.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guillemette L, Lacroix M, Battista MC et al. TNFα dynamics during the oral glucose tolerance test vary according to the level of insulin resistance in pregnant women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:1862–9. 10.1210/jc.2013-4016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lacroix M, Battista MC, Doyon M et al. Lower vitamin D levels at first trimester are associated with higher risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol 2014;51:609–16. 10.1007/s00592-014-0564-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Feng R, Guo F et al. Targeted metabolomic analysis reveals the association between the postprandial change in palmitic acid, branched-chain amino acids and insulin resistance in young obese subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015;108:84–93. 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padberg I, Peter E, Gonzalez-Maldonado S et al. A new metabolomic signature in type-2 diabetes mellitus and its pathophysiology. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e85082 10.1371/journal.pone.0085082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho JE, Larson MG, Vasan RS et al. Metabolite profiles during oral glucose challenge. Diabetes 2013;62:2689–98. 10.2337/db12-0754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant CC, Stewart AW, Scragg R et al. Vitamin D during pregnancy and infancy and infant serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration. Pediatrics 2014;133:e143 10.1542/peds.2013-2602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lagiou P, Hsieh C-C, Samoli E et al. Associations of placental weight with maternal and cord blood hormones. Ann Epidemiol 2013;23:669–73. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]