Abstract

Objective

To investigate the efficacy of Honevo, a topical 90% medical-grade kanuka honey, and 10% glycerine (honey product) as a treatment for facial acne.

Design

Randomised controlled trial with single blind assessment of primary outcome variable.

Setting

Outpatient primary care from 3 New Zealand localities.

Participants

Of 136 participants aged between 16 and 40 years with a diagnosis of acne and baseline Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) for acne score of ≥2.68, participants were randomised to each treatment arm.

Interventions

All participants applied Protex, a triclocarban-based antibacterial soap twice daily for 12 weeks. Participants randomised to the honey product treatment arm applied this directly after washing off the antibacterial soap, twice daily for 12 weeks.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was ≥2 point decrease in IGA score from baseline at 12 weeks. Secondary outcomes included mean lesion counts and changes in subject-rated acne improvement and severity at weeks 4 and 12, and withdrawals for worsening acne.

Results

4/53 (7.6%) participants in the honey product group and 1/53 (1.9%) of participants in the control group had a ≥ 2 improvement in IGA score at week 12, compared with baseline, OR (95% CI) for improvement 4.2 (0.5 to 39.3), p=0.17. There were 15 and 14 participants who withdrew from the honey product group and control group, respectively.

Conclusions

This randomised controlled trial did not find evidence that addition of medical-grade kanuka honey in combination with 10% glycerine to standard antibacterial soap treatment is more effective than the use of antibacterial soap alone in the treatment of acne.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12614000003673; Results.

Keywords: COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE, Randomised controlled trial, Kanuka honey

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a 12-week randomised controlled trial comparing the addition of topical 90% medical-grade kanuka honey and 10% glycerine to standard antibacterial soap wash with antibacterial soap wash alone.

Given the nature of the investigational products participant blinding was not possible.

The primary outcome variable (Investigator's Global Assessment of Acne) was assessed by investigators blinded to randomisation throughout the study period.

Introduction

Acne is a very prevalent inflammatory disorder of the skin. A recent review reports an 85% prevalence in those aged between 12 and 24 years of age in the USA.1 For many people, acne persists into adulthood. One study reports that in men and women aged between 40 and 49 years about 5% still have acneiform rashes.2

Acne has a range of manifestations including non-inflamed comedones, and also inflamed and painful pustules and nodules. Four underlying pilosebaceous processes are responsible for the clinical manifestations: ductal obstruction from keratinocyte desquamation and proliferation, increased sebum production under androgenic influence, Propionibacterium acne colonisation and finally, as a consequence, inflammation. Current therapeutic interventions address one or more of these processes. The main treatments are systemic or topical antibiotics, hormones, retinoid therapy, or a combination regimen.3 Retinoids, in particular, have many contraindications and problematic side effects including skin irritation and systemic retinoid sequale. They are teratogenic which makes their use difficult in women of childbearing age. P. acne resistance, in relation to antibiotic use, is an emerging concern.4 Acne control is often not acceptable for many patients and new treatment options are needed.

Honey is a complementary therapy dating back to Hippocrates.5 The robust evaluation of medical-grade honey is of interest because of its apparent antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and potential immunomodulatory actions.6 7 We recently reported a randomised controlled trial (RCT) that found a significant improvement in rosacea severity using a topical 90% medical-grade kanuka honey/10% glycerine formulation compared to a standard topical treatment (cetomacrogol). The honey treatment had high patient acceptability.8 The study reported here is an RCT investigating the efficacy of the medical-grade kanuka honey product in the topical management of acne.

Methods

In a single-blind RCT, patients with acne were recruited in three ways: by presentation to their general practitioner, by a practice database for records of those with acne, or directly through advertisement; in three New Zealand centres, Wellington, Auckland and Tauranga.

Adults aged between 16 and 40 years, with a baseline facial Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) score of ≥ 2 (table 1)9 were recruited.

Table 1.

Investigator's Global Assessment for acne

| Score | Description | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Clear | Clear skin with no inflammatory or non-inflammatory lesions |

| 1 | Almost clear | Rare non-inflammatory lesions with no more than one inflammatory lesion |

| 2 | Mild | Greater than grade 1; some non-inflammatory lesions with no more than a few inflammatory lesions (Papules or pustules only, no nodular lesions) |

| 3 | Moderate | Greater than grade 2; up to many non-inflammatory lesions and may have some inflammatory lesions but no more than one small nodular lesion |

| 4 | Severe | Greater than grade 3; up to many non-inflammatory and inflammatory lesions but no more than a few nodular lesions |

Exclusion criteria were: current requirement for systemic corticosteroids or antibiotics treatment or use in the previous 4 weeks; current requirement for topical corticosteroids or antibiotics; change in oral contraceptive therapy in the past 3 months; systemic retinoid in the past 2 months; known or suspected allergy to honey or Protex Gentle Antibacterial Soap/triclocarban; any significant systemic illness or other condition which the investigators felt presented a safety risk or potentially affected the participant's ability to complete the study.

Three study visits were: the baseline first visit, designated week 0, where after informed consent was obtained, baseline measurement occurred, and participants were randomised to a treatment arm. At the second and third visits, after 4 and 12 weeks, primary and secondary outcome measures, adverse effects and general feedback, were obtained.

Treatment applications

All participants were asked to apply Protex, an triclocarban-based antibacterial soap twice daily to affected areas according to the manufacturer's instructions. Participants randomised to the Honevo, 90% medical-grade kanuka honey with 10% glycerine (honey product) group were asked to apply the honey formulation to affected areas, following the antibacterial soap application, twice daily between 30 and 60 min, and then wash it off with warm water. The control group just used the soap. Adherence was assessed by daily recording of applications by participants and a check for diary completeness at each visit.

Randomisation and blinding

Participants were randomised to the honey product or control arms using a concealed computer-generated sequence. After consent was obtained, the investigator opened an opaque envelope revealing the randomised treatment for the participant. A second investigator performed the IGA at each visit masked as to treatment allocation. The honey product group was asked not to use the treatment on the day of assessment to maintain masking.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of participants who had a greater than two-point decrease in IGA score for acne vulgaris at week 12 relative to baseline.

Secondary outcome measures were as follows:

Mean IGA score at weeks 4 and 12;

Mean lesion count at weeks 4 and 12. Lesion count was subdivided into inflamed and non-inflamed lesions. Lesions were graded using the Leeds revised acne grading system;10

Change in subject-rated global acne improvement using visual analogue score (VAS) at weeks 4 and 12;

Subject-rated global acne severity VAS at week 4 compared to baseline;

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI);

Daily self-reported use (applications per day);

Weekly self-reported global acne severity (VAS scale);

Withdrawals due to worsening of acne.

Sample size and study power

There is a lack of prior study using honey as a topical therapy for acne. We therefore based our power calculations on an anticipated response of 25–50% given the 0-point to 5-point score structure and maximum 4-point improvement available within the ordinal IGA used to assess the primary outcome variable. A total of 124 participants (62 in each group) had 80% power at 5% significance to detect an absolute difference of 25% responders. Recruitment of 136 participants allowed for a 10% drop-out rate. Treatment arms were blocked by 136 to ensure equal participant numbers within each.

Statistical methods

Analysis was per protocol. Logistic regression was used to estimate the OR for the proportion of participants with an IGA score change from baseline of ≥2 at 12 weeks, and for the proportion of withdrawals due to worsening acne, comparing honey product to control. For the latter, this was unable to be estimated due to no withdrawals for worsening acne in the control group.

The Mann-Whitney test with Hodges-Lehmann estimator and Moses CI was used for IGA (an ordinal scale variable), and soap count (where the data was skewed and an appropriate transformation could not be identified).

Proportional odds logistic regression was also used for IGA. The p value for the unadjusted analysis is identical to that for the Mann-Whitney test, but this method allows for adjusting variables. This method estimates a common OR for all combinations of summing the lower ranked values versus the higher ranked values, and in this analysis a higher value for this OR meant that the honey product had a better outcome than control.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with, as appropriate, the baseline value as a continuous covariate, was used for the VAS improvement, VAS severity at weeks 4 and 12, DLQI, and weekly self-reported VAS. Normality assumptions were reasonably well met for these analyses.

For the lesion count variables the data was skewed and for the ANCOVA normality assumptions were better met on the logarithm transformed scale. Exponentiation of the difference in logarithms can be interpreted as the ratio of mean values. SAS V.9.3 was used.

Results

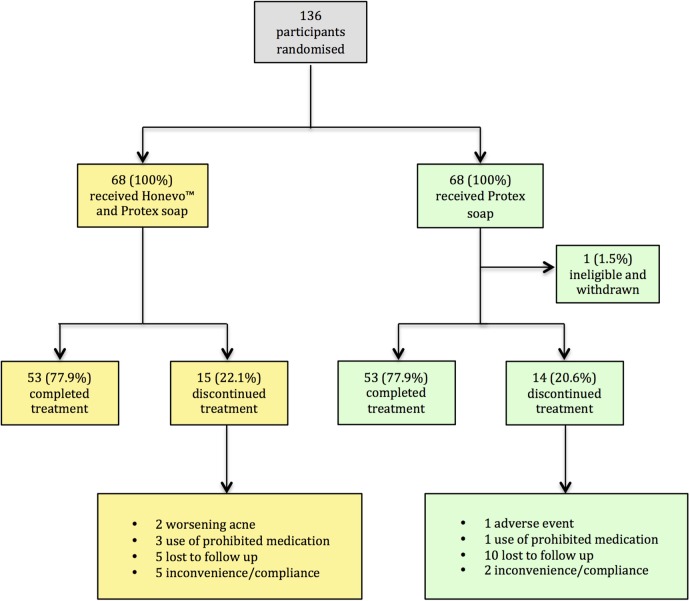

The flow of participants is shown in figure 1. Sixty-eight participants were randomised to each treatment with similar proportions of males and females, and equivalent duration of acne in each (table 2).

Figure 1.

Participant flow from randomisation to study completion or withdrawal.

Table 2.

Participant ages at enrolment and diagnosis and sex

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Minimum to Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrolment (years) | |||

| All N=135 | 21.2 (5.8) | 18.3 (17.1 to 23.3) | 16.0 to 39.7 |

| Honey product N=68 | 21.5 (6.4) | 18.5 (17.1 to 23.5) | 16.0 to 39.7 |

| Control N=67 | 20.9 (5.2) | 18.3 (17.2 to 23.3) | 16.0 to 38.4 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| All N=135 | 13.9 (2.7) | 13 (13 to 14) | 10 to 28 |

| Honey product N=68 | 13.7 (2.7) | 13 (12.5 to 24) | 10 to 28 |

| Control N=67 | 14.2 (2.6) | 14 (13 to 14) | 11 to 26 |

Shortly after randomisation to the control arm, one participant was found to exceed the age criteria and was withdrawn with no data collected. There were 15 (22.1%) withdrawals in the honey product group (two worsening acne, three use of prohibited medication, five lost to follow-up and five participants who withdrew because of non-adherence due to reported inconvenience of the treatment). There were 14 (20.6%) withdrawals in the control group (one adverse event involving a minor skin reaction, one use of a prohibited medication, 10 were lost to follow-up and two participants withdrew due to inconvenience of the treatment).

Primary outcome

There were 4/53 (7.6%) participants in the honey product group and 1/53 (1.9%) of participants in the control only group who had a ≥2 improvement in IGA assessment at week 12, compared with baseline; OR (95% CI) 4.2 (0.5 to 39.3), p=0.17.

Secondary outcomes

The Hodges-Lehmann estimator (95% CI) comparing IGA scores for honey product with control at 4 weeks was 0 (0 to 0), p=0.54 and at 12 weeks was 0 (0 to 0), p=0.33. Proportional odds logistic regression for the IGA score at week 4 estimated the OR (95% CI) for improvement of 1.2 (0.6 to 2.4), p=0.54 without adjustment for baseline IGA score and 2.1 (1.0 to 4.3), p=0.055, after adjustment. Proportional odds logistic regression for the IGA score at week 12 estimated the OR (95% CI) for improvement of 1.4 (0.7 to 2.9), p=0.33, without adjustment for baseline, and 2.0 (CI 0.9 to 4.2), p=0.075, after adjustment. These latter estimates are consistent with weak evidence of improvement in the honey product group compared to control. Data summaries for IGA are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) scores at each visit for participants in honey product and control treatment arms with change in IGA score from baseline at visits 2 and 3

| Variable | N (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Honey product | Control | All | |

| IGA—visit 1 | N=68 | N=67 | N=135 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 21 (30.9) | 23 (34.3) | 44 (32.6) |

| 3 | 37 (54.4) | 38 (56.7) | 75 (55.6) |

| 4 | 10 (14.7) | 6 (9.0) | 16 (11.9) |

| IGA—visit 2 | N=61 | N=56 | N=117 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 8 (13.1) | 3 (5.4) | 11 (9.4) |

| 2 | 24 (39.3) | 27 (48.2) | 51 (43.6) |

| 3 | 24 (39.3) | 18 (32.1) | 42 (35.9) |

| 4 | 5 (8.2) | 8 (14.3) | 13 (11.1) |

| IGA—visit 3 | N=53 | N=53 | N=106 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 10 (18.9) | 7 (13.2) | 17 (16.0) |

| 2 | 25 (47.2) | 24 (45.3) | 49 (46.2) |

| 3 | 15 (28.3) | 18 (34.0) | 33 (31.3) |

| 4 | 3 (5.7) | 4 (7.6) | 7 (6.6) |

| IGA—visit 2 minus IGA—visit 1 | N=61 | N=56 | N=117 |

| −2 | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) |

| −1 | 26 (42.6) | 15 (26.8) | 41 (35.0) |

| 0 | 30 (49.2) | 35 (62.5) | 65 (55.6) |

| 1 | 4 (6.7) | 6 (10.7) | 10 (8.6) |

| IGA—visit 3 minus IGA—visit 1 | N=53 | N=53 | N=106 |

| −2 | 4 (7.6) | 1 (1.9) | 5 (4.7) |

| −1 | 25 (47.2) | 21 (39.6) | 46 (43.4) |

| 0 | 23 (43.4) | 26 (49.1) | 49 (46.2) |

| 1 | 1 (1.9) | 5 (9.4) | 6 (5.7) |

The difference (95% CI) in logarithm inflamed lesion count for honey product minus control after adjustment for baseline at week 4 was −0.28 (−0.61 to 0.06), p=0.11, ratio of mean lesion counts by exponentiation 0.76 (0.54 to 1.06). At week 12, the difference (95% CI) was −0.29 (−0.65 to 0.07), p=0.11, ratio of mean lesion counts by exponentiation 0.75 (0.52 to 1.07). The difference (95% CI) in logarithm non-inflamed lesion count, honey product minus control, at week 4 count was −0.12 (−0.42 to 0.18), p=0.44, ratio of mean lesion counts by exponentiation 0.89 (0.66 to 1.20), and at week 12 −0.06 (−0.40 to 0.28), p=0.72, ratio of mean lesion counts by exponentiation 0.94 (0.67 to 1.32).

The difference (95% CI) in subject-rated global acne VAS improvement adjusted for baseline, honey product minus control, at week 4 was 9.6 (3.7 to 15.6), p=0.002; and at week 12, 11.0 (4.4 to 17.6), p=0.001.

The difference (95% CI) in subject-rated global acne severity VAS adjusted for baseline, honey product minus control, at week 4 was –3.7 (–10.2 to 2.7), p=0.26; and at week 12 −6.8 (−14.8 to 1.2), p=0.095.

The difference (95% CI) in DLQI adjusted for baseline, honey product minus control, at week 4 was 0.12 (−0.73 to 0.97), p=0.77; and at week 12 0.14 (−0.75 to 1.03), p=0.76.

The Hodges-Lehmann estimate (95% CI) of the difference in daily self-reported use of treatment, between the two study groups was −7 (−13 to −1), p=0.01, with honey product users having less applications.

Self-reported global acne severity VAS comparing honey product and control alone, adjusted for week 1 baseline demonstrated moderate evidence for improved scores using honey product between weeks 5 and 11.

Withdrawal due to worsening acne occurred in 2/68 (2.9%) of the honey product group and none of the control group.

Adverse events

There were 111 adverse events recorded, of which 64 were deemed by investigators to be unrelated to the study treatment. There were 47 adverse events, 23 in the honey product group and 24 in the control group which were assessed to be related to the study treatment. All involved skin-related symptoms including oily, dry and stinging skin, contact dermatitis and worsening acne.

Discussion

This RCT has not found evidence that the addition of 90% medical-grade kanuka honey in combination with 10% glycerine to standard antibacterial soap treatment is more effective than the use of antibacterial soap alone in the treatment of acne.

Although there was no evidence of improvement in acne severity using the primary outcome criteria of ≥2-point change in IGA, a more detailed analysis treating the outcome as an ordinal variable, with adjustment for baseline severity, suggested that there may be weak evidence of an improved score in the honey product arm compared to control at 12 weeks, with an OR for an improved category of IGA of 2.0 (p=0.075). In this study, there were an unexpectedly high number of withdrawals and a small number of participants who actually improved by the above criterion. This, in turn, was likely related to a floor effect for the measurement instrument because around one-third of participants could not have achieved this ≥2-point change in IGA unless their acne entirely resolved, as their baseline IGA score was 2. There were 15 (22.1%) and 14 (20.6%) withdrawals for the honey product and control groups, respectively.

Secondary outcomes mostly showed no evidence of benefit from the use of honey product for the treatment of acne. Subject-rated improvement according to a VAS at weeks 4 and 12 was better for the honey treatment. There may have been subjective assessment bias however, because we could not mask participants to honey treatment. In addition, this outcome variable may be subject to type I error rate inflation as it was a secondary outcome among a number of other secondary outcome variables.

Comparison with other studies

We are not aware of an RCT considering a honey-based therapy for acne. A previous study, which found the honey product an effective treatment for rosacea, was of similar design and size, and used a primary outcome of a blinded, 7-point, IGA of Rosacea Severity Score (IGA-RSS) ≥2. There were 34.3% of participants randomised to honey product, and 17.4% receiving control who achieved the primary outcome compared to 7.6% and 1.9% in the acne study. Given the wider scope for improvement in the Rosacea study (7 points as compared to 5 points in the IGA scale) and the higher proportion of participants reaching the primary outcome criterion in both arms, further studies of honey in acne may wish to consider these factors in study design. Furthermore, a number of participant characteristics may be relevant. The mean age of participants with chronic acne, present on average for 14 years, was 21 years. The total study duration was 12 weeks, and the diary component of the data collection required daily entry of multiple parameters. We considered that the motivation of an individual to adhere to such a treatment and record-keeping regimen, and subsequent quality of data collected, is likely dependent on the perceived acne severity, however, it is also possible that adherence in teenagers with acne is poor, even when they are bothered by their acne. The general lifestyle and severity of acne among a young cohort of participants, not currently taking more intensive treatments such as retinoids or antibiotics, may not lead to robust participation in our study. There were 22 participants who withdrew for reasons of inconvenience or were lost to follow-up. By contrast to this, the rosacea study reported only one withdrawal for similar reasons, the average participant age was 58.2 years, and the study duration 8 weeks.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study include the coapplication of antibacterial soap within the active honey product treatment arm, thereby allowing the examination of a true additive effect. Using the IGA in combination with lesion counts as outcome variables allows for the pleomorphic expression of acne within a group, while also providing an absolute quantitative measure of improvement. The blinding of the assessors generating these outcomes to specific treatment allocations, also allowed for avoidance of assessment bias.

The primary, but unavoidable limitation for this study was the lack of blinding for participants because the honey product tasted and smelt of honey (90% kanuka honey and 10% glycerine). It is therefore not possible to produce an inert control that matches these characteristics without containing a high concentration of honey. Further issues were apparent in terms of data collection, with evidence of poor and delayed diary completion and likely recall bias, as well as the specific reasons given for withdrawal.

Implications for clinical practice

The results presented do not support a benefit of using honey in addition to a common over-the-counter antibacterial soap. This knowledge may inform both patients and clinicians when considering alternative therapies for acne, and the study furthers the knowledge base for commonly used and recommended alternative therapies for dermatological conditions.

Implications of future research

While an inflammatory process is prominent in the pathogenesis of acne, the relative contribution of different molecular and immunological pathways are not fully elucidated,11 although it is clear that bacteria such as P. acnes influence this process. The potential mechanism of action was not the focus of this study, however, it is possible that the anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties of kanuka honey may not exert an influence relevant to the specific pathogenic pathways in acne. This may also explain the negative findings. In relation to this, effective delivery of honey to the site of inflammation and/or infection within a lesion must also be considered, and will be influenced by the type of lesion and whether open or closed. While we recorded lesions as inflammatory or non-inflammatory, further details were not recorded that may have been relevant to outcomes in particular subgroups. The use of such a honey product as a targeted topical acne therapy, for example, in open lesions only, is worthy of future study.

Protex antibacterial soap is a widely available ‘over-the-counter’ treatment for acne, and containing the bacteriostatic agent triclocarban. Incorporating antibacterial soap application as both the control and within the treatment arm has allowed us to examine the effect of the kanuka honey product when added to antibacterial soap treatment. Direct comparison of an antibacterial soap to the honey product in a subsequent non-inferiority trial would reveal whether kanuka honey represents a natural treatment option for acne suffers, with equivalent efficacy as a widely available, over-the-counter antibacterial soap.

Overall, there is a need for robust evidence to support or rebuke claims by alternative therapies marketed for common medical ailments, some of which have a serious impact on quality of life. Particular focus on constantly improving the methodology used to answer these research questions will allow cost-effective, well-powered and high-quality RCTs to further advance this field.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this RCT has not shown the addition of medical-grade kanuka honey in combination with 10% glycerine to standard antibacterial soap wash to be of clinical benefit in the treatment of acne. The study has, however, highlighted significant methodological and statistical considerations that will be of value in further studies of such natural products. It is clear that the method of data collection in studies of this length must be both robust and convenient to patients, and to facilitate this key, related outcome measures should be used. Taking this into consideration, future studies concerning topical honey should consider the use of ‘e-Diaries’, simplified data-recording methods and direct comparison of the honey-based product with standard treatment.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Honey Acne Study Team, Medical Research Institute of New Zealand, Wellington, New Zealand: Judith Riley, Anna Hunt, Tony Mallon, Mark Holliday.

Contributors: IB, JF, RB contributed to the study concept and design. CH, DS, AC, CT, CH and BM contributed to acquisition of the data. AS, IB, RB and MW drafted the manuscript. All the authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and also to administrative, technical and material support. MW contributed to statistical analysis. IB had access to all the data on the study and takes responsibility of the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This study was entirely funded by HoneyLab, who provided the Honevo (90% medical-grade kanuka honey and 10% glycerine).

Disclaimer: The sponsor had no role in the study design, data collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report and the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Central Health and Disabilities Ethics Committee, New Zealand (13/CEN/119).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Patient-level data available from the corresponding author. Consent was not obtained from participants for data sharing, but the presented data are anonymised and the risk of identification is low. Data may be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Judith Riley, Anna Hunt, Tony Mallon, and Mark Holliday

References

- 1.Bhate K, Williams H. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 2013;168:474–85. 10.1111/bjd.12149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunliffe W, Gould D. Prevalence of facial acne vulgaris in late adolescence and in adults. BMJ 1979;1:1109–10. 10.1136/bmj.1.6171.1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandoval L, Hartel K, Feldman S. Current and future evidence-based acne treatment: a review. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014;15:173–92. 10.1517/14656566.2014.860965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leccia M, Auffret N, Poli F et al. Topical acne treatments in Europe and the issue of antimicrobial resistance. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015;29:1485–92. 10.1111/jdv.12989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hippocrates. On Ulcers. (400BC) Internet Classics Archive. Translated by F Adams at. http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/ulcers.5.5.html.

- 6.Leong A, Herst P, Harper J. Indigenous New Zealand honeys exhibit multiple anti-inflammatory activities. Innate Immun 2012;18:459–66. 10.1177/1753425911422263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu J, Carter D, Turnbull L et al. The effect of New Zealand kanuka, manuka and clover honeys on bacterial growth dynamics and cellular morphology varies according to the species. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e55898 10.1371/journal.pone.0055898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braithwaite I, Hunt A, Riley J et al. Randomised controlled trial of topical kanuka honey for the treatment of rosacea, accepted for publication. BMJ Open 2015;5:e00765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.2005. Administration, U. S. D. of H. and H. S. F. and D. & (CDER), C. for D. E. and R. Guidance for Industry Acne Vulgaris: Developing Drugs for Treatment. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm071292.pdf.

- 10.O'brien S, Lewis J, Cunliffe W. The Leeds revised acne grading system. J Dermatolog Treat 1998;9:215–20. 10.3109/09546639809160698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanghetti E. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2013;6:27–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]