Abstract

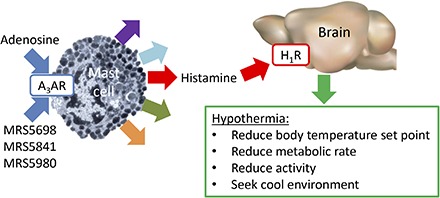

Adenosine can induce hypothermia, as previously demonstrated for adenosine A1 receptor (A1AR) agonists. Here we use the potent, specific A3AR agonists MRS5698, MRS5841, and MRS5980 to show that adenosine also induces hypothermia via the A3AR. The hypothermic effect of A3AR agonists is independent of A1AR activation, as the effect was fully intact in mice lacking A1AR but abolished in mice lacking A3AR. A3AR agonist–induced hypothermia was attenuated by mast cell granule depletion, demonstrating that the A3AR hypothermia is mediated, at least in part, via mast cells. Central agonist dosing had no clear hypothermic effect, whereas peripheral dosing of a non–brain-penetrant agonist caused hypothermia, suggesting that peripheral A3AR-expressing cells drive the hypothermia. Mast cells release histamine, and blocking central histamine H1 (but not H2 or H4) receptors prevented the hypothermia. The hypothermia was preceded by hypometabolism and mice with hypothermia preferred a cooler environmental temperature, demonstrating that the hypothermic state is a coordinated physiologic response with a reduced body temperature set point. Importantly, hypothermia is not required for the analgesic effects of A3AR agonists, which occur with lower agonist doses. These results support a mechanistic model for hypothermia in which A3AR agonists act on peripheral mast cells, causing histamine release, which stimulates central histamine H1 receptors to induce hypothermia. This mechanism suggests that A3AR agonists will probably not be useful for clinical induction of hypothermia.

Introduction

Maintenance of a constant, warm body temperature is an essential component of mammalian physiology. Hypothermia can be caused by cold exposure that overwhelms the animal’s ability to generate and conserve body heat. Hypothermia, exemplified by hibernation and torpor, is also a physiologic mechanism used by small mammals to conserve energy (Geiser, 2004; Melvin and Andrews, 2009). Such endogenous hypothermia is actively achieved via disengaging brown adipose tissue, reducing physical activity and vasodilation, and seeking a cool environment (Heller and Ruby, 2004; Lute et al., 2014). Hypothermia can also be elicited pharmacologically by many drugs and neurotransmitters [e.g., Clark and Lipton (1985)]. Finally, hypothermia is used clinically to minimize tissue injury and improve survival, for example, after neonatal hypoxia or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (Arrich et al., 2012; Azzopardi et al., 2014).

The mouse is an attractive model for studying thermal biology because core body temperature (Tb) changes occur more rapidly and with a much greater magnitude than in larger mammals. Mice have a greater surface area/volume ratio and thus a disproportionally greater energetic cost of staying warm (Hudson and Scott, 1979; Abreu-Vieira et al., 2015). Although the magnitude of Tb fluctuation is less in humans than in mice, it is likely that the neural circuitry controlling Tb is conserved.

Adenosine is a purine nucleoside that is predominantly found intracellularly but also has an extracellular role. Extracellular adenosine comes from intracellular adenosine and hydrolysis of extracellular nucleotides (ATP, ADP, AMP) by ectonucleotidases (Chen et al., 2013). Extracellular adenosine levels can rise dramatically under conditions of cellular injury (Schubert et al., 1997), prolonged wakefulness (Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 1997; Basheer et al., 2004), hypoxia (Van Wylen et al., 1986), metabolic stress (Minor et al., 2001), and high intensity exercise (Dworak et al., 2007). Adenosine signals through four G protein-coupled receptors. The A1 and A3 adenosine receptors (ARs) inhibit adenylyl cyclase, whereas A2AAR and A2BAR stimulate it.

The ability of adenosine to induce hypothermia has been known for over 80 years (Bennet and Drury, 1931). Following identification of the four receptors, Anderson et al. (1994) used the available ligands to suggest that adenosine analogs cause hypothermia via adenosine A1 receptor (A1AR) in the central nervous system. Further evidence for a role for A1AR includes prevention of AMP hypothermia by an A1AR antagonist (Muzzi et al., 2013), loss of the hypothermic effect of N6-cyclohexyladenosine in A1AR null (Adora1−/−) mice (Johansson et al., 2001), and induction of a hypothermic state with A1AR agonist (N6-cyclohexyladenosine) injection into the nucleus of the solitary tract (Tupone et al., 2013). These observations firmly established that A1AR activation can cause hypothermia (Fredholm et al., 2011).

There is also evidence that adenosine can induce hypothermia via non-A1AR mechanisms. For example, hypothermia produced by N6-R-phenylisopropyladenosine was only partially attenuated in the Adora1−/− mouse (Yang et al., 2007). Also, hypothermia from high dose AMP was attributed to erythrocyte uptake of intact AMP, and this hypothermia was intact in mice lacking any one of the four adenosine receptors (Daniels et al., 2010). Most informative is the observation that N6-R-phenylisopropyladenosine-induced hypothermia was attenuated in adenosine A3 receptor (A3AR) null (Adora3−/−) mice, directly implicating the A3AR’s involvement in hypothermia (Yang et al., 2010). In rodents, the A3AR is expressed in neutrophils, basophils, mast cells, and other cells mediating inflammatory responses (Borea et al., 2015). Use of Adora3−/− mice conclusively demonstrated a role for A3AR in triggering mouse mast cell degranulation (Salvatore et al., 2000), whereas the A3AR may not be important in human mast cell degranulation (Auchampach et al., 1997; Gomez et al., 2011; Rudich et al., 2012). The availability of potent, specific mouse A3AR agonists (Jacobson, 2013) allowed us to investigate the hypothermia induced by A3AR agonists and the contributing mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Male C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), Adora1−/− [on a mixed background, provided by Dr. Jurgen Schnermann (Sun et al., 2001)], and Adora3−/− [on a C57BL/6 background, provided by Dr. Stephen Tilley under a materials transfer agreement with Merck (Salvatore et al., 2000)]. Mice were singly housed at ∼21–22°C with a 12-hour light-dark cycle. Chow (NIH-07; Harlan/Teklad, Madison, WI) and water were available ad libitum. Mice were studied ≥7 days after any operation or prior treatment. Studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and St. Louis University.

Drugs.

Compounds and vehicles were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless synthesized in house. MRS5698, 2-(3,4-difluorophenylethynyl)-N6-(3-chlorobenzyl)-(N)-methanocarba-adenosine-5′-methyluronamide (Tosh et al., 2012), was dissolved in 4:1 (v/v) PEG300/warm Solutol HS15, then an equal volume of 10% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin in water was added during vortexing. MRS5841, N6-3-chlorobenzyl-2-(3-sulfophenylethynyl) (N)-methanocarba-adenosine-5′-methyluronamide, was dissolved in saline (Paoletta et al., 2013). MRS5980, (1S,2R,3S,4R,5S)-4-(2-((5-chlorothiophen-2-yl)ethynyl)-6-(methylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl)-2,3-dihydroxy-N-methylbicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-1-carboxamide (Tosh et al., 2014), was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and adjusted to 30% dimethyl sulfoxide/0.5% methylcellulose/water. Other compounds (vehicles) with references for dose choice are: histamine type 1 receptor (H1R) antagonist pyrilamine (saline) (Zarrindast et al., 2005; Kitanaka et al., 2007), H2R antagonist zolantidine (saline) (Kitanaka et al., 2007), and H4R antagonist JNJ7777120 (10% ethanol in saline) (Cowden et al., 2013). Mice were treated with escalating doses of compound 48/80 in saline on 5 consecutive days as described (Ge et al., 2006). Plasma stability, Caco-2 cell permeability, and parallel artificial membrane permeability at pH 7.4 (Pion PAMPA method) of MRS5698, MRS5841, and MRS5980 were measured by GVK Biosciences, Hyderabad, India.

Body Temperature and Activity Telemetry.

Core body temperature and activity were measured continuously by telemetry (Starr Life Sciences, Oakmont, PA) using ER4000 energizer/receivers, G2 E-mitters implanted intraperitoneally, and VitalView software, with data collected each minute. Unless noted otherwise, the average Tb response was calculated using the first 60 minutes after A3AR agonist dosing. Hypothermia duration is the time of Tb < 35°C during the interval from dosing to 300 minutes. Activity is the sum of counts from 10–60 minutes after A3AR agonist administration. Inhibitors were dosed 15 minutes before A3AR agonist.

Central Infusions.

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (80/10 mg/kg i.p.). Sterile guide cannulas (5.25 mm, 26 gauge; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) were unilaterally implanted into the lateral ventricle (coordinates relative to bregma: –0.34 mm anterior, 1.0 mm lateral, and +1.7 mm ventral) and fixed with dental cement (Parkell, Edgewood, NY). Compounds in 5 μl were infused (0.5 μl/min) through a 33-gauge cannula protruding 0.5 mm past the tip of the guide cannula using PE-50 tubing fitted to a 5-μl syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV). Cannula positions were verified by postmortem histologic analysis.

Antinociception.

Paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) in a mouse sciatic nerve chronic constriction injury (CCI)–neuropathic pain model was measured as described (Bennett and Xie, 1988; Chen et al., 2012). The PWT (in grams) on both the constricted and uninjured side were measured before constriction (day 0), at peak mechano-allodynia (day 7), and at the indicated times after drug administration for both the constricted side and the uninjured contralateral paw. ED50 values at 1 hour after drug treatment were calculated from dose-response data curve-fitted using the least sum of square method by a normalized four-parameter, variable-slope nonlinear analysis of the %Reversal of Mechano-allodynia using GraphPad Prism (v5.03; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). The %Reversal of Mechano-allodynia = (PWT1h − PWTD7)/(PWTD0 − PWTD7) × 100. Chronic constriction injury data are expressed as mean ± S.D. and were analyzed by repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction using GraphPad Prism.

Other Procedures.

Indirect calorimetry was performed using an Oxymax/CLAMS (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) at 22°C as described (Lute et al., 2014). Environmental temperature preference was measured using an in-house apparatus by continuous video monitoring of the position of the mouse in a 45-cm thermal gradient, nominally 18–36°C (Lute et al., 2014). Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M. Significance (two-tailed P < 0.05) was determined using SigmaPlot using t test or analysis of variance followed by post-hoc Holm-Sidak multiple comparison tests.

Results

MRS5698 Causes Hypothermia and Decreased Physical Activity via A3AR.

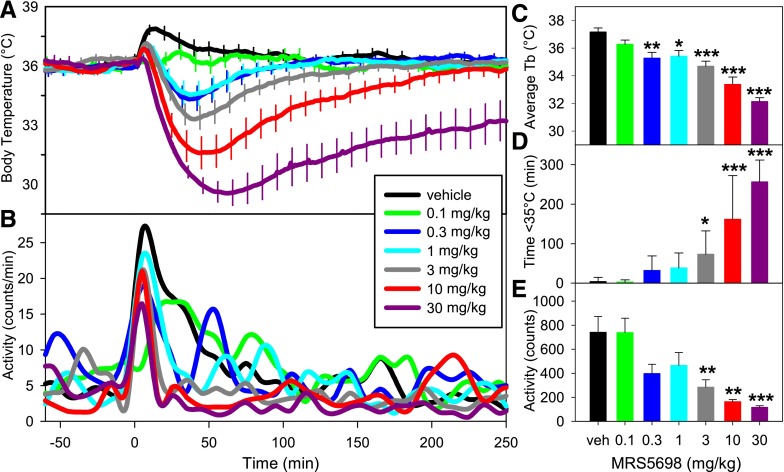

To understand the role of A3AR agonism in hypothermia, we used a highly selective agonist, MRS5698 (Tosh et al., 2012). Handling of mice during vehicle treatment caused an increase in activity and body temperature (Tb), which resolved within an hour. In contrast, MRS5698 treatment caused a dose-dependent drop in Tb, ranging from nonsignificant reduction (with 0.1 mg/kg of the rise in Tb seen with vehicle injection) to a profound, prolonged hypothermia at higher doses (0.3 to 30 mg/kg) (Fig. 1A). The mean Tb during the first hour after dosing is a sensitive measure of hypothermia (Fig. 1C). Higher MRS5698 doses progressively reduced the nadir Tb and increased the duration of the hypothermia (Fig. 1D). The hypothermia was accompanied by reduced physical activity (Fig. 1, B and E).

Fig. 1.

MRS5698 causes dose-dependent hypothermia and decreased physical activity. (A) Tb response to the indicated MRS5698 dose injected intraperitoneally into C57BL/6J mice. (B) Physical activity response to indicated MRS5698 dose in arbitrary units each minute. The effect of MRS5698 on (C) mean Tb (of 1–60 minutes), (D) duration of hypothermia, and (E) physical activity calculated from the data in (A) and (B). Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 6–13/group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Every tenth S.E.M. is shown in (A). In (B) data are graphed as splines and S.E.M.s were omitted for visual clarity.

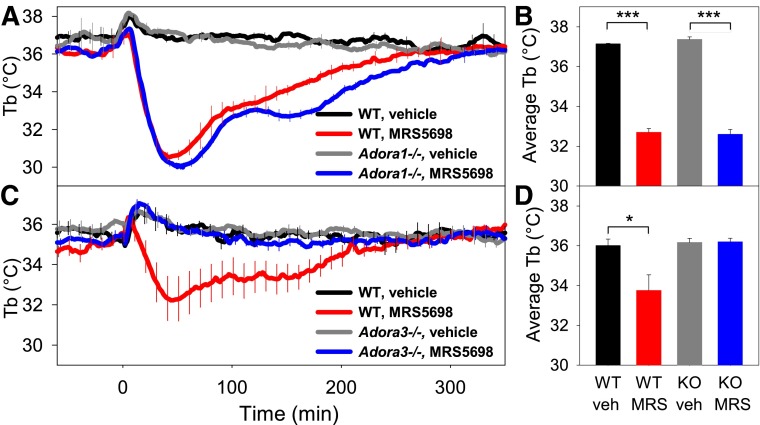

The receptor selectivity of MRS5698 for A3AR determined in binding assays (>3000-fold versus A1AR in both mouse and human) was confirmed in vivo using Adora1−/− and Adora3−/− mice since hypothermic actions attributed to some A1AR agonists may be attributable to A3AR (Yang et al., 2010) (and unpublished observations). MRS5698 effects on Tb nadir, hypothermia duration, and physical activity were similar in wild-type (WT) and Adora1−/− mice (Fig. 2, A and B, and not shown). In contrast, MRS5698-induced hypothermia was completely abolished in Adora3−/−mice (Fig. 2, C and D). These data demonstrate that the hypothermic effects of MRS5698 are produced via A3AR, with no contribution from A1AR.

Fig. 2.

MRS5698-induced hypothermia is lost in Adora3−/− mice. Tb response to MRS5698 (10 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle in (A, B) Adora1−/− (KO) and C57BL/6J (WT) mice and (C, D) Adora3−/− (KO) and C57BL/6J (WT) mice. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 3–5/group in a crossover design, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Every tenth S.E.M. is shown.

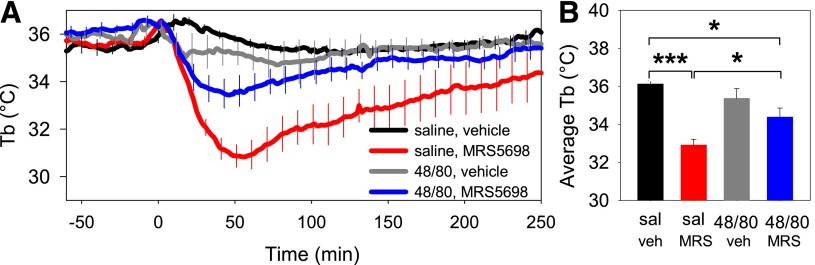

A3AR Agonist Acts via Mast Cells to Induce Hypothermia.

To test for a role of mast cells in A3AR agonist–mediated hypothermia, we pretreated mice with multiple ascending doses of compound 48/80, which depletes mast cell granules (Ge et al., 2006). Hypothermia occurred after each dose of compound 48/80, including the last dose (not shown), suggesting that granule depletion may have been partial. One day after the last 48/80 treatment, the hypothermic effect of MRS5698 was attenuated (Fig. 3). These data suggest that mast cells contribute to the hypothermic response to MRS5698.

Fig. 3.

Pretreatment with compound 48/80 attenuates MRS5698 hypothermia. (A) C57BL/6J mice were pretreated with compound 48/80 (48/80) or saline (sal) for 5 days (see Materials and Methods). On the next day, at time 0, mice were treated with MRS5698 (10 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 6/group, every tenth S.E.M. is shown. (B) Mean Tb (of 1–60 minutes) calculated from the data in (A), *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

We next tested the effect of two doses of MRS5698 given 4 hours apart (Supplemental Fig. 1). Mice treated only once with MRS5698 showed the expected hypothermia and hypoactivity, whereas a second MRS5698 injection did not reduce Tb or activity, indicating that mice have a refractory period after a hypothermic/hypoactive response to A3AR activation.

A3AR Agonist Acts Both Outside and Within the Central Nervous System.

The hypothermia caused by MRS5698 could occur via peripheral and/or central A3ARs, because this agonist crosses the blood-brain barrier (Little et al., 2015). Consistent with the in vivo results, MRS5698 has a high intrinsic permeability across an artificial membrane (P = 67 ± 21 10−6 cm/s). It is also a substrate for intestinal transport (Caco-2 efflux ratio = 86) [Table 1; Tosh et al. (2015)].

TABLE 1.

In vitro parameters of A3AR agonists

| Property, Units | MRS5698a | MRS5841 | MRS5980a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permeability, Caco-2b | Papp (A–B, 10−6 cm/s) | 0.08 | 0.10 (60% recovery) | 2.20 (81% recovery) |

| Papp (B–A, 10−6 cm/s) | 7.26 | 1.32 (71% recovery) | 35.8 (93% recovery) | |

| Efflux ratio | 86 | 13 | 16.3 | |

| Permeability, PAMPAc pH7.4 | P (10−6 cm/s) | 67.1 ± 21.4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 46.7 ± 2.1 |

| Stability, plasma (human) | % remaining at 2 hours | ND | 91% | 100% |

| Stability, plasma (mouse) | % remaining at 2 hours | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Stability, plasma (rat) | % remaining at 2 hours | 100% | 100% | 97% |

ND, not determined; PAMPA, parallel artificial membrane permeability assay.

MRS5698 data are from Tosh et al. (2015); some of the MRS5980 data are from Tosh et al. (2014).

Caco-2 permeability and plasma stability data are mean of two replicates.

PAMPA permeability data are mean ± S.D. of three replicates.

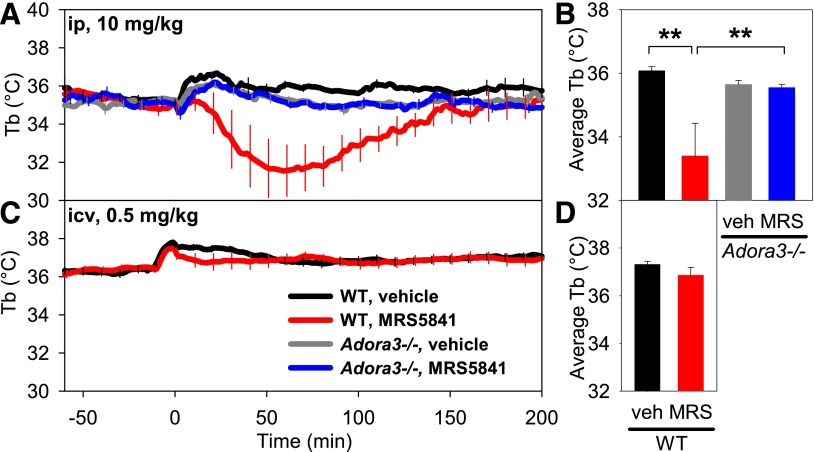

The effects of intraperitoneal versus intracerebroventricular dosing were compared using MRS5841, a sulfonated A3AR agonist with selectivity and potency similar to MRS5698 but improved aqueous solubility and restricted central nervous system (CNS) penetration (Paoletta et al., 2013). MRS5841 was not detectably permeable across an artificial membrane, although it is probably a transporter substrate (Caco-2 efflux ratio = 13) (Table 1). MRS5841, given intraperitoneally at 10 mg/kg, produced hypothermia similar to MRS5698, with no effect in Adora3−/− mice, confirming the drug’s A3AR selectivity (Fig. 4, A and B). Mice given a 20-fold lower dose of MRS5841 intracerebroventricularly showed no clear hypothermia (Fig. 4, C and D). These data suggest that A3AR agonists cause hypothermia via binding to receptors outside the central nervous system.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the hypothermic response to peripheral versus central dosing with A3AR agonist MRS5841. (A) Tb and (B) mean Tb response to MRS5841 (10 mg/kg) or vehicle injected intraperitoneally into C57BL/6J (WT) or Adora3−/− (A3AR KO) mice. MRS5841 causes hypothermia in wild-type but not Adora3−/− mice. (C) Tb and (D) mean Tb response to MRS5841 (0.5 mg/kg = 25 nmol) or vehicle injected intracerebroventricularly into C57BL/6J mice. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 4–7/group in (A), n = 15/group in (C); every tenth S.E.M. is shown, **P < 0.01.

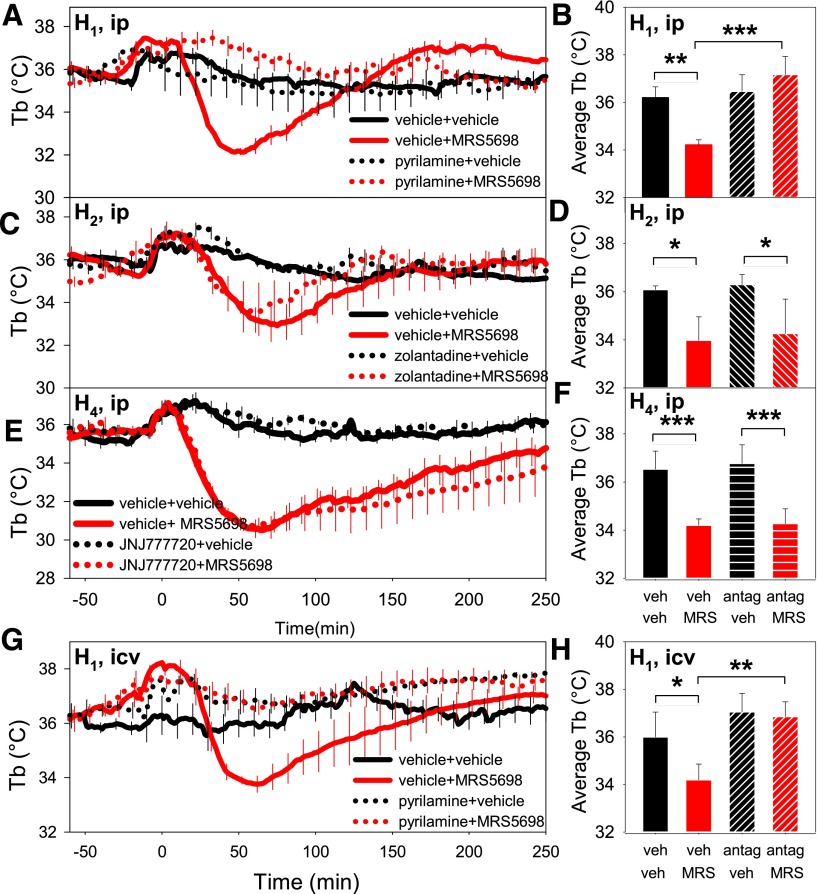

A3AR-Agonist Hypothermia Is Mediated by Central Histamine H1 Receptors.

Histamine is one of the bioactive molecules released by mast cells (Fozard et al., 1996). To examine the role of histamine receptors in A3AR agonist–induced hypothermia, we pretreated mice with histamine antagonists. The H1R antagonist pyrilamine (10 mg/kg i.p.) completely inhibited MRS5698-induced hypothermia (Fig. 5, A and B). In contrast, pretreatment with either the brain-penetrant H2R antagonist zolantidine (10 mg/kg i.p.) (Gogas and Hough, 1988) or the brain-penetrant H4R antagonist JNJ7777120 (10 mg/kg i.p.) (Hsieh et al., 2010) had no effect on MRS5698-induced hypothermia (Fig. 5, C–F). Pretreatment with intracerebroventricular pyrilamine (0.5 mg/kg) also completely inhibited the hypothermic response to MRS5698 (Fig. 5, G and H). The 0.5 mg/kg dose had no effect when given intraperitoneally (data not shown), indicating that the inhibition of hypothermia resulted from inhibition of central, and not peripheral, H1R. These results suggest that the central H1Rs are functionally downstream from the A3AR receptor in the hypothermia response to MRS5698.

Fig. 5.

A3AR agonist–induced hypothermia is mediated by central histamine H1 receptors. (A) Tb and (B) mean Tb (of 1–60 minutes) values in response to pretreatment with H1R antagonist pyrilamine (10 mg/kg i.p.) or saline followed 15 minutes later by MRS5698 (10 mg/kg i.p., at time 0) or vehicle in C57BL/6J mice. (C) Tb and (D) mean Tb in response to pretreatment with H2R antagonist zolantidine (10 mg/kg i.p.) or saline followed 15 minutes later by MRS5698 (10 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle. (E) Tb and (F) mean Tb in response to pretreatment with H4R antagonist JNJ7777120 (10 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle. (G) Tb and (H) mean Tb in response to pretreatment with intracerebroventricular pyrilamine (0.5 mg/kg) or saline followed 15 minutes later by MRS5698 (10 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle. Data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 4/group; every tenth S.E.M. is shown in (A), (C), (E), and (G); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

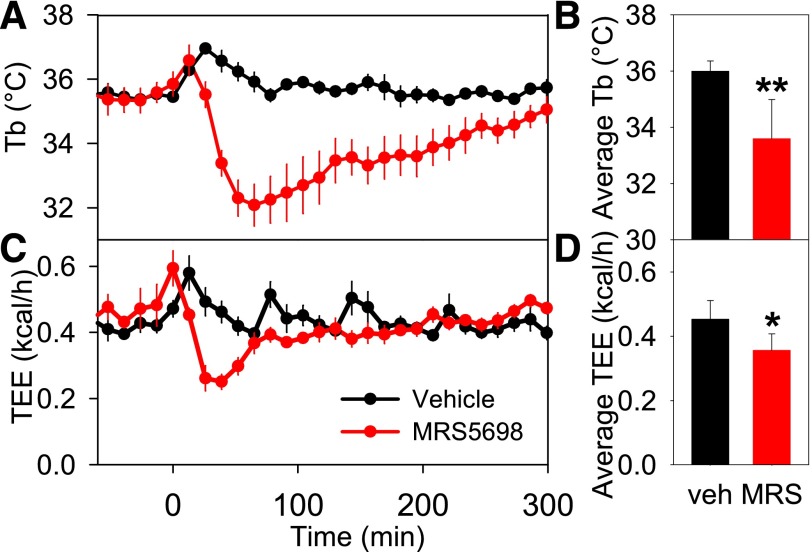

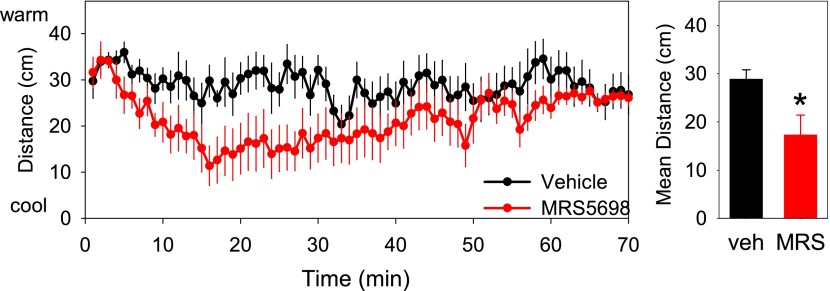

A3AR-Agonist Hypothermia Is a Coordinated Physiologic Response.

MRS5698 administration caused a reduction in metabolic rate, which preceded the reduction in Tb (Fig. 6), suggesting that the hypothermia was being actively driven. When hypothermia is the targeted physiologic state with a reduced Tb set point, the animal prefers a cool environment to attain the hypothermia. In contrast, in hypothermia without a reduced Tb set point, the animal prefers a warm environment (Gordon, 2012). Mice treated with MRS5698 chose a cooler place in a thermal gradient and moved less compared with vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 7). This indicates that the hypothermic state is a coordinated physiologic response to A3AR agonist treatment.

Fig. 6.

MRS5698 reduces metabolic rate prior to Tb. Effect of MRS5698 (10 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle dosed to C57BL/6J mice (A) Tb, (B) mean Tb (of 1–60 minutes), (C) total energy expenditure (TEE), and (D) mean TEE (of 1–60 minutes). The TEE falls before Tb (nadir at ∼30 minutes versus ∼60 minutes for Tb). Parameters were measured every 13 minutes; data are mean ± S.E.M., n = 6/group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Fig. 7.

Mice treated with MRS5698 seek cooler temperatures. C57BL/6J mice were treated with MRS5698 (3 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle and placed in a thermal gradient. The mice were monitored by video, and the (A) position within the gradient and the (C) velocity were calculated. The mean (B) position and (D) velocity for each mouse from 6 to 35 minutes after dosing was calculated. Mean ± S.E.M., n = 6/group, crossover design; *P < 0.05.

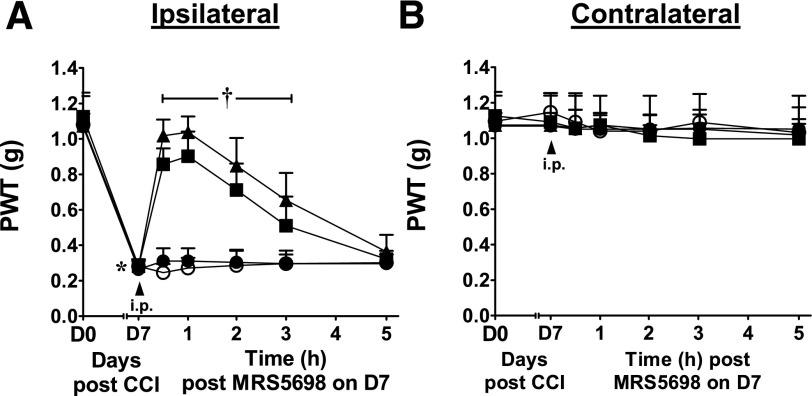

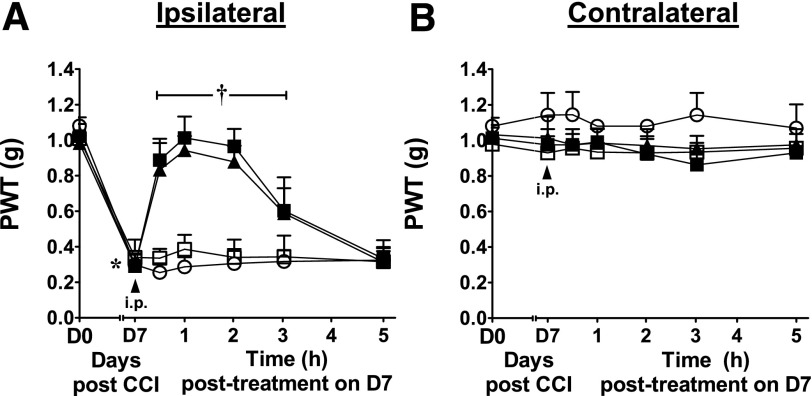

The Analgesic Effects of A3AR Agonists Are Independent of Hypothermia.

A3AR agonism is an effective treatment for neuropathic pain (Chen et al., 2012; Little et al., 2015). When peak mechano-allodynia develops [day 7 following chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve (Bennett and Xie, 1988)], intraperitoneal administration of MRS5698, but not vehicle, rapidly and dose-dependently (0.1–1 mg/kg) reversed the allodynia, with maximal effect within 1 hour (ED50 0.2 mg/kg; 95% CI = 0.2–0.3) (Fig. 8A). The uninjured contralateral paws were not affected by treatment with MRS5698 (Fig. 8B). The MRS5698 dose sufficient for analgesia is below doses producing hypothermia.

Fig. 8.

Dose-dependent reversal of neuropathic pain by MRS5698. PWT measured in the ipsilateral (A) and contralateral (B) paws before chronic constriction injury (CCI; day 0), after 7 days of constriction and before drug treatment (day 7), and at the indicated times after administration of MRS5698 (●, 0.1; ▪, 0.3; ▴, 1 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle (○, 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide in saline). Mean ± S.D., n = 5/group; *P < 0.05 day 7 versus day 0, †P < 0.05 indicated time versus day 7.

We tested whether the antinociceptive effect requires hypothermia. Pyrilamine pretreatment (10 mg/kg i.p.) had no effect on the reversal of neuropathic pain by MRS5698 (3 mg/kg i.p.) (Fig. 9A). Pyrilamine alone also had no effect on neuropathic pain or in the contralateral paws (Fig. 9, A and B).

Fig. 9.

Pyrilamine does not reverse the analgesic effect of MRS5698. PWT measured in the ipsilateral (A) and contralateral (B) paws before chronic constriction injury (CCI; day 0), after 7 days of constriction and before drug treatment (day 7), and at the indicated times after administration of saline then vehicle (○), saline then MRS5698 (▴), pyrilamine then vehicle (□), or pyrilamine then MRS5698 (▪). The pyrilamine (10 mg/kg i.p.) or its vehicle (saline) was given 15 minutes before MRS5698 (3 mg/kg i.p.) or its vehicle (0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide in saline). Mean ± S.D., n = 5/group; *P < 0.05 day 7 versus day 0, †P < 0.05 indicated time versus day 7.

The relationship between hypothermia and analgesia was also probed with an orally bioavailable A3AR agonist, MRS5980 (Tosh et al., 2014). Oral MRS5980 caused hypothermia and reduced activity with a dose of 30 mg/kg, but not 10 mg/kg (Supplemental Fig. 2). Oral MRS5980 rapidly and dose-dependently reversed allodynia, with maximal effect within 1 hour (ED50 0.23 mg/kg; 95% CI = 0.15–0.35) and no effect in the contralateral paws (Supplemental Fig. 3). The lack of reversal of the analgesic effect of MRS5698 by pyrilamine and the lower doses of MRS5698 and MRS5980 required for analgesia compared with hypothermia demonstrate that hypothermia is not required for the antinociceptive effects of A3AR agonists.

Discussion

We show that A3AR agonists acting peripherally cause hypothermia and that these actions are independent of A1AR activation. The data support a model, discussed below, in which peripheral A3AR agonist causes mast cell activation and histamine release leading to activation of central H1R.

A Site of A3AR-Agonist Action Is the Mouse Mast Cell.

Local extracellular adenosine levels typically increase under extreme conditions such as hypoxia, injury, or high metabolic stress (Van Wylen et al., 1986; Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 1997; Schubert et al., 1997; Minor et al., 2001; Basheer et al., 2004; Dworak et al., 2007). The A3AR appears to have a modest affinity for adenosine, being tuned for the elevated adenosine levels occurring with extreme physiologic situations (Fredholm, 2014). A3ARs are present on immune/inflammatory cells, such as mast cells (Hua et al., 2008), basophils, eosinophils, neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and microglial cells [reviewed in Borea et al. (2015)]. However, it is notable that mast cell A3AR level and biology depend on the species and tissue source, with A3AR not present in some human mast cells (Auchampach et al., 1997; Gomez et al., 2011; Rudich et al., 2012). Adenosine, acting via A3AR on mast cells, causes histamine release and airway hyper-responsiveness in mice (Tilley et al., 2000, 2003; Zhong et al., 2003; Hua et al., 2008). In our study, compound 48/80, which causes mast cell granule depletion [but not depletion of histamine from neurons (Metcalfe et al., 1997)], attenuated A3AR agonist–induced hypothermia, implicating mast cells as an initiator of the events. The partial inhibition may be attributable to incomplete degranulation by compound 48/80 or to A3AR agonist also acting at other cells to initiate hypothermia via histamine release. We conclude that A3AR agonists are acting on mast cells but cannot rule out a contribution from additional cell types.

Hypothermia was caused by intraperitoneal dosing of MRS5841, an intrinsically impermeant compound that does not penetrate the CNS (Paoletta et al., 2013). In contraposition, although mast cells are found in the brain and account for a considerable fraction of brain histamine content (Tabarean, 2015), dosing MRS5841 centrally did not produce hypothermia. These results suggest that hypothermia is caused by binding to A3AR receptors outside the blood-brain barrier. It is possible that other A3AR agonist–induced effects such as reduced locomotion, behavioral depression, and neuroprotection (Fedorova et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2010; Paoletta et al., 2013; Borea et al., 2015) are also initiated via peripheral A3AR.

Central Histamine Receptors and Hypothermia.

Histamine was first shown to cause hypothermia in 1911 (Dale and Laidlaw, 1911). More recent experiments suggested a brain site of action and the involvement of H1R (Shaw, 1971; Bugajski and Zacny, 1981; Haas et al., 2008). We show that signaling via CNS histamine H1R is required for A3AR agonist–mediated hypothermia. It is not typically thought that peripheral histamine crosses the blood-brain barrier [but see Shaw (1971)]. Possible explanations are that histamine acts at a circumventricular region without a functional blood-brain barrier or that histamine itself increases blood-brain barrier permeability (Boertje et al., 1989). The important point is that hypothermia occurs following peripheral A3AR activation and is dependent on histamine action in the brain. Although we have not determined which neurons carry the relevant H1Rs, the preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus is a thermoregulatory region previously identified as a site for histamine-triggered hypothermia (Bugajski and Zacny, 1981; Colboc et al., 1982). However, there are also opposing observations—direct injection of an H1R agonist into the preoptic area produces hyperthermia, not hypothermia (Lundius et al., 2010; Sethi et al., 2012; Tabarean, 2015). Further investigations are needed to untangle the mechanistic details of central histamine action in hypothermia.

A3AR Hypothermia and Other Forms of Hypothermia.

Many drugs cause hypothermia. Mast cell activation, as demonstrated for A3AR, may be the mechanism for a significant proportion. Examples of signals to mast cells causing hypothermia include activation of the FcεRI IgE receptor (Finkelman, 2007), neurotensin receptor (Kandasamy et al., 1991), Toll-like receptor 4 (by lipopolysaccharide) (Nautiyal et al., 2009), and Toll-like receptor 7 (Hayashi et al., 2008). Although we did not measure blood pressure, hypotension probably accompanies hypothermia because of the mast cell activation (Hannon et al., 1995). The hypotension may contribute to the hypothermia, but these can be dissociated [hypothermia without hypotension (Lute et al., 2014) and hypotension without hypothermia (Makabe-Kobayashi et al., 2002)].

Other forms of hypothermia are independent of mast cells. Mast cells do not contribute to the reduced body temperature of the inactive circadian phase (Nautiyal et al., 2009) and A1AR hypothermia is elicited via a neuronal mechanism (Tupone et al., 2013). Similarly, there is no documented role for mast cells in the hypothermia of torpor or hibernation. It is likely that different mechanisms trigger hypothermia, depending on the instigating stimulus, with the mechanistic details currently unknown for many.

Therapeutic Uses of A3AR Agonists.

Hypothermia blunts inflammation, such as the “cytokine storm” of sepsis, and reduces metabolic demand. Endogenous hypothermia can be part of a coordinated hypometabolic response to limit tissue damage and increase survival. In clinical medicine, hypothermia is induced to allow hypoperfusion during surgery and in ominous situations such as after neonatal hypoxia (Azzopardi et al., 2014) or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (Debaty et al., 2014). Therapeutic hypothermia can be induced by physical cooling at the surface and internally. Pharmacological induction of hypothermia is an appealing clinical concept, with the dual goal of lowering body temperature while minimizing counter-regulatory responses such as shivering, non-shivering thermogenesis, and increased sympathetic tone. However, A3AR agonism is probably not an optimal pharmacologic approach, owing to the unclear role of A3AR in primate mast cell activation and to the undesired effects of mast cell activation, such as bronchoconstriction and vascular leakage. The latter effects likely also render H1R agonists suboptimal for clinical hypothermia induction.

The clinical utility of A3AR agonists is being explored for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, glaucoma and dry eye, pain, and certain cancers (Fishman et al., 2012; Borea et al., 2015). Since hypothermia is anti-inflammatory, does the hypothermia contribute to A3AR efficacy for these indications? We show for two different A3AR agonists that antinociception is achieved at doses that are below those eliciting hypothermia. Since hypothermic effects are greatly amplified in small mammals (e.g., mouse) compared with large mammals (e.g., human), antinociceptive A3AR agonist doses are unlikely to cause hypothermia at clinically relevant doses (e.g., a 1- to 2-mg dose of IB-MECA, twice daily PO, for treatment of psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis [Fishman et al., 2012)]. Furthermore, H1R blockade did not block antinociception but did prevent hypothermia. Thus, hypothermia does not contribute to or interfere with the antinociceptive effect of A3AR agonists.

In conclusion, the results support a model in which A3AR agonists activate mast cells in the periphery, causing histamine release. The histamine acts on central H1R to lower the Tb set point and cause hypothermia. Importantly, hypothermia is not required for the antinociceptive effects of A3AR agonists. These results demonstrate that adenosine can cause hypothermia through A3AR, in addition to A1AR, activation and provide mechanistic detail for the route by which A3AR agonism induces hypothermia. The data suggest that A3AR agonists are not ideal for clinical induction of hypothermia. We have used a mouse model in which hypothermic effects are amplified in intensity in comparison with larger species. Furthermore, the beneficial use of such agonists in humans at very low doses in treating chronic diseases is not likely to be complicated by or to be dependent on hypothermic effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anna Panyutin for technical assistance, Jurgen Schnermann for discussions, Ana Olivera and Dean Metcalfe for the mast cell image, and www.clker.com for the brain image.

Abbreviations

- A1AR

adenosine A1 receptor

- A3AR

adenosine A3 receptor

- CNS

central nervous system

- H1R

histamine type 1 receptor

- PWT

paw withdrawal threshold

- Tb

core body temperature

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Carlin, Salvemini, Gavrilova, Jacobson, Reitman.

Conducted experiments: Carlin, Xiao, Piñol, Chen, Gavrilova.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Tosh, Jacobson.

Performed data analysis: Carlin, Xiao, Salvemini, Gavrilova, Reitman.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Carlin, Salvemini, Gavrilova, Jacobson, Reitman.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [ZIA DK075063; ZIA DK031117] and by the National Cancer Institute [RO1CA169519]. D.S. is a cofounder of BioIntervene Inc.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Abreu-Vieira G, Xiao C, Gavrilova O, Reitman ML. (2015) Integration of body temperature into the analysis of energy expenditure in the mouse. Mol Metab 4:461–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R, Sheehan MJ, Strong P. (1994) Characterization of the adenosine receptors mediating hypothermia in the conscious mouse. Br J Pharmacol 113:1386–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrich J, Holzer M, Havel C, Müllner M, Herkner H. (2012) Hypothermia for neuroprotection in adults after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD004128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchampach JA, Rizvi A, Qiu Y, Tang XL, Maldonado C, Teschner S, Bolli R. (1997) Selective activation of A3 adenosine receptors with N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide protects against myocardial stunning and infarction without hemodynamic changes in conscious rabbits. Circ Res 80:800–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzopardi D, Strohm B, Marlow N, Brocklehurst P, Deierl A, Eddama O, Goodwin J, Halliday HL, Juszczak E, Kapellou O, et al. TOBY Study Group (2014) Effects of hypothermia for perinatal asphyxia on childhood outcomes. N Engl J Med 371:140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basheer R, Strecker RE, Thakkar MM, McCarley RW. (2004) Adenosine and sleep-wake regulation. Prog Neurobiol 73:379–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet DW, Drury AN. (1931) Further observations relating to the physiological activity of adenine compounds. J Physiol 72:288–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ, Xie YK. (1988) A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain 33:87–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boertje SB, Le Beau D, Williams C. (1989) Blockade of histamine-stimulated alterations in cerebrovascular permeability by the H2-receptor antagonist cimetidine. Neuropharmacology 28:749–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borea PA, Varani K, Vincenzi F, Baraldi PG, Tabrizi MA, Merighi S, Gessi S. (2015) The A3 adenosine receptor: history and perspectives. Pharmacol Rev 67:74–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugajski J, Zacny E. (1981) The role of central histamine H1- and H2-receptors in hypothermia induced by histamine in the rat. Agents Actions 11:442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Eltzschig HK, Fredholm BB. (2013) Adenosine receptors as drug targets--what are the challenges? Nat Rev Drug Discov 12:265–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Janes K, Chen C, Doyle T, Bryant L, Tosh DK, Jacobson KA, Salvemini D. (2012) Controlling murine and rat chronic pain through A3 adenosine receptor activation. FASEB J 26:1855–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark WG, Lipton JM. (1985) Changes in body temperature after administration of acetylcholine, histamine, morphine, prostaglandins and related agents: II. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 9:479–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colboc O, Protais P, Costentin J. (1982) Histamine-induced rise in core temperature of chloral-anaesthetized rats: mediation by H2-receptors located in the preopticus area of hypothalamus. Neuropharmacology 21:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowden JM, Yu F, Challapalli M, Huang JF, Kim S, Fung-Leung WP, Ma JY, Riley JP, Zhang M, Dunford PJ, et al. (2013) Antagonism of the histamine H4 receptor reduces LPS-induced TNF production in vivo. Inflamm Res 62:599–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale HH, Laidlaw PP. (1911) Further observations on the action of beta-iminazolylethylamine. J Physiol 43:182–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels IS, Zhang J, O’Brien WG, 3rd, Tao Z, Miki T, Zhao Z, Blackburn MR, Lee CC. (2010) A role of erythrocytes in adenosine monophosphate initiation of hypometabolism in mammals. J Biol Chem 285:20716–20723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debaty G, Maignan M, Savary D, Koch FX, Ruckly S, Durand M, Picard J, Escallier C, Chouquer R, Santre C, et al. (2014) Impact of intra-arrest therapeutic hypothermia in outcomes of prehospital cardiac arrest: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med 40:1832–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworak M, Diel P, Voss S, Hollmann W, Strüder HK. (2007) Intense exercise increases adenosine concentrations in rat brain: implications for a homeostatic sleep drive. Neuroscience 150:789–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova IM, Jacobson MA, Basile A, Jacobson KA. (2003) Behavioral characterization of mice lacking the A3 adenosine receptor: sensitivity to hypoxic neurodegeneration. Cell Mol Neurobiol 23:431–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelman FD (2007) Anaphylaxis: lessons from mouse models. J Allergy Clin Immunol 120:506–515; quiz 516–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman P, Bar-Yehuda S, Liang BT, Jacobson KA. (2012) Pharmacological and therapeutic effects of A3 adenosine receptor agonists. Drug Discov Today 17:359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fozard JR, Pfannkuche HJ, Schuurman HJ. (1996) Mast cell degranulation following adenosine A3 receptor activation in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 298:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB. (2014) Adenosine--a physiological or pathophysiological agent? J Mol Med (Berl) 92:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Johansson S, Wang YQ. (2011) Adenosine and the regulation of metabolism and body temperature. Adv Pharmacol 61:77–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge ZD, Peart JN, Kreckler LM, Wan TC, Jacobson MA, Gross GJ, Auchampach JA. (2006) Cl-IB-MECA [2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methylcarboxamide] reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice by activating the A3 adenosine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319:1200–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser F. (2004) Metabolic rate and body temperature reduction during hibernation and daily torpor. Annu Rev Physiol 66:239–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogas KR, Hough LB. (1988) Effects of zolantidine a brain-penetrating H2-receptor antagonist, on naloxone-sensitive and naloxone-resistant analgesia. Neuropharmacology 27:357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez G, Zhao W, Schwartz LB. (2011) Disparity in FcεRI-induced degranulation of primary human lung and skin mast cells exposed to adenosine. J Clin Immunol 31:479–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CJ. (2012) Thermal physiology of laboratory mice: Defining thermoneutrality. J Therm Biol 37:654–685. [Google Scholar]

- Haas HL, Sergeeva OA, Selbach O. (2008) Histamine in the nervous system. Physiol Rev 88:1183–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon JP, Pfannkuche HJ, Fozard JR. (1995) A role for mast cells in adenosine A3 receptor-mediated hypotension in the rat. Br J Pharmacol 115:945–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Cottam HB, Chan M, Jin G, Tawatao RI, Crain B, Ronacher L, Messer K, Carson DA, Corr M. (2008) Mast cell-dependent anorexia and hypothermia induced by mucosal activation of Toll-like receptor 7. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295:R123–R132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller HC, Ruby NF. (2004) Sleep and circadian rhythms in mammalian torpor. Annu Rev Physiol 66:275–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh GC, Chandran P, Salyers AK, Pai M, Zhu CZ, Wensink EJ, Witte DG, Miller TR, Mikusa JP, Baker SJ, et al. (2010) H4 receptor antagonism exhibits anti-nociceptive effects in inflammatory and neuropathic pain models in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 95:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Chason KD, Fredholm BB, Deshpande DA, Penn RB and Tilley SL (2008) Adenosine induces airway hyperresponsiveness through activation of A3 receptors on mast cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 122:107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JW, Scott IM. (1979) Daily torpor in the laboratory mouse, mus musculus var. albino. Physiol Zool 52:205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA. (2013) Structure-based approaches to ligands for G-protein-coupled adenosine and P2Y receptors, from small molecules to nanoconjugates. J Med Chem 56:3749–3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B, Halldner L, Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA, Poelchen W, Giménez-Llort L, Escorihuela RM, Fernández-Teruel A, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Xu XJ, et al. (2001) Hyperalgesia, anxiety, and decreased hypoxic neuroprotection in mice lacking the adenosine A1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:9407–9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy SB, Hunt WA, Harris AH. (1991) Role of neurotensin in radiation-induced hypothermia in rats. Radiat Res 126:218–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitanaka J, Kitanaka N, Tatsuta T, Morita Y, Takemura M. (2007) Blockade of brain histamine metabolism alters methamphetamine-induced expression pattern of stereotypy in mice via histamine H1 receptors. Neuroscience 147:765–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JW, Ford A, Symons-Liguori AM, Chen Z, Janes K, Doyle T, Xie J, Luongo L, Tosh DK, Maione S, et al. (2015) Endogenous adenosine A3 receptor activation selectively alleviates persistent pain states. Brain 138:28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundius EG, Sanchez-Alavez M, Ghochani Y, Klaus J, Tabarean IV. (2010) Histamine influences body temperature by acting at H1 and H3 receptors on distinct populations of preoptic neurons. J Neurosci 30:4369–4381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lute B, Jou W, Lateef DM, Goldgof M, Xiao C, Piñol RA, Kravitz AV, Miller NR, Huang YG, Girardet C, et al. (2014) Biphasic effect of melanocortin agonists on metabolic rate and body temperature. Cell Metab 20:333–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makabe-Kobayashi Y, Hori Y, Adachi T, Ishigaki-Suzuki S, Kikuchi Y, Kagaya Y, Shirato K, Nagy A, Ujike A, Takai T, et al. (2002) The control effect of histamine on body temperature and respiratory function in IgE-dependent systemic anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 110:298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melvin RG, Andrews MT. (2009) Torpor induction in mammals: recent discoveries fueling new ideas. Trends Endocrinol Metab 20:490–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe DD, Baram D, Mekori YA. (1997) Mast cells. Physiol Rev 77:1033–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor TR, Rowe MK, Soames Job RF, Ferguson EC. (2001) Escape deficits induced by inescapable shock and metabolic stress are reversed by adenosine receptor antagonists. Behav Brain Res 120:203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzi M, Blasi F, Masi A, Coppi E, Traini C, Felici R, Pittelli M, Cavone L, Pugliese AM, Moroni F, et al. (2013) Neurological basis of AMP-dependent thermoregulation and its relevance to central and peripheral hyperthermia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33:183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nautiyal KM, McKellar H, Silverman AJ, Silver R. (2009) Mast cells are necessary for the hypothermic response to LPS-induced sepsis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296:R595–R602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletta S, Tosh DK, Finley A, Gizewski ET, Moss SM, Gao ZG, Auchampach JA, Salvemini D, Jacobson KA. (2013) Rational design of sulfonated A3 adenosine receptor-selective nucleosides as pharmacological tools to study chronic neuropathic pain. J Med Chem 56:5949–5963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porkka-Heiskanen T, Strecker RE, Thakkar M, Bjorkum AA, Greene RW, McCarley RW. (1997) Adenosine: a mediator of the sleep-inducing effects of prolonged wakefulness. Science 276:1265–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudich N, Ravid K, Sagi-Eisenberg R. (2012) Mast cell adenosine receptors function: a focus on the a3 adenosine receptor and inflammation. Front Immunol 3:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore CA, Tilley SL, Latour AM, Fletcher DS, Koller BH, Jacobson MA. (2000) Disruption of the A(3) adenosine receptor gene in mice and its effect on stimulated inflammatory cells. J Biol Chem 275:4429–4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert P, Ogata T, Marchini C, Ferroni S, Rudolphi K. (1997) Protective mechanisms of adenosine in neurons and glial cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci 825:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi J, Sanchez-Alavez M, Tabarean IV. (2012) Loss of histaminergic modulation of thermoregulation and energy homeostasis in obese mice. Neuroscience 217:84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GG. (1971) Hypothermia produced in mice by histamine acting on the central nervous system. Br J Pharmacol 42:205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Samuelson LC, Yang T, Huang Y, Paliege A, Saunders T, Briggs J, Schnermann J. (2001) Mediation of tubuloglomerular feedback by adenosine: evidence from mice lacking adenosine 1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:9983–9988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabarean IV. (2015) Histamine receptor signaling in energy homeostasis. Neuropharmacology DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.04.011 [published ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley SL, Tsai M, Williams CM, Wang ZS, Erikson CJ, Galli SJ, Koller BH. (2003) Identification of A3 receptor- and mast cell-dependent and -independent components of adenosine-mediated airway responsiveness in mice. J Immunol 171:331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley SL, Wagoner VA, Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Koller BH. (2000) Adenosine and inosine increase cutaneous vasopermeability by activating A(3) receptors on mast cells. J Clin Invest 105:361–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosh DK, Deflorian F, Phan K, Gao ZG, Wan TC, Gizewski E, Auchampach JA, Jacobson KA. (2012) Structure-guided design of A(3) adenosine receptor-selective nucleosides: combination of 2-arylethynyl and bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane substitutions. J Med Chem 55:4847–4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosh DK, Finley A, Paoletta S, Moss SM, Gao ZG, Gizewski ET, Auchampach JA, Salvemini D, Jacobson KA. (2014) In vivo phenotypic screening for treating chronic neuropathic pain: modification of C2-arylethynyl group of conformationally constrained A3 adenosine receptor agonists. J Med Chem 57:9901–9914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosh DK, Padia J, Salvemini D, Jacobson KA. (2015) Efficient, large-scale synthesis and preclinical studies of MRS5698, a highly selective A3 adenosine receptor agonist that protects against chronic neuropathic pain. Purinergic Signal 11:371–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupone D, Madden CJ, Morrison SF. (2013) Central activation of the A1 adenosine receptor (A1AR) induces a hypothermic, torpor-like state in the rat. J Neurosci 33:14512–14525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wylen DG, Park TS, Rubio R, Berne RM. (1986) Increases in cerebral interstitial fluid adenosine concentration during hypoxia, local potassium infusion, and ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 6:522–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JN, Tiselius C, Daré E, Johansson B, Valen G, Fredholm BB. (2007) Sex differences in mouse heart rate and body temperature and in their regulation by adenosine A1 receptors. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 190:63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JN, Wang Y, Garcia-Roves PM, Björnholm M, Fredholm BB. (2010) Adenosine A(3) receptors regulate heart rate, motor activity and body temperature. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 199:221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Khalilzadeh A, Rezayat SM, Sahebgharani M, Djahanguiri B. (2005) Influence of intracerebroventricular administration of histaminergic drugs on morphine state-dependent memory in the step-down passive avoidance test. Pharmacology 74:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Shlykov SG, Molina JG, Sanborn BM, Jacobson MA, Tilley SL, Blackburn MR. (2003) Activation of murine lung mast cells by the adenosine A3 receptor. J Immunol 171:338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.