Abstract

Cancer treatment evolves through oncology clinical trials. Cancer trials are multimodality and complex. Assuring high quality data are available to answer not only study objectives but also questions not anticipated at study initiation is the role of quality assurance. The National Cancer Institute reorganized its cancer clinical trials program in 2014. The National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) was formed and within it, established a Diagnostic Imaging and Radiation Therapy Quality Assurance Organization. This organization is IROC, the Imaging and Radiation Oncology Core Group, comprised of six quality assurance centers that provide Imaging and Radiation Therapy Quality Assurance for the NCTN. Sophisticated imaging is used for cancer diagnosis, treatment, and management as well as for the image-driven technologies to plan and execute radiation treatment. Integration of imaging and radiation oncology data acquisition, review, management, and archive strategies are essential for trial compliance and future research. Lessons learned from previous trials are and provide evidence to support diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy data acquisition in NCTN trials.

Introduction

Clinical trials are the mainstay for evolving treatment standards of care for cancer patients. In 2014 the National Cancer Institute (NCI) transformed its infrastructure to conduct cancer clinical trials more efficiently and effectively within a network. Imaging and comprehensive data acquisition strategies are essential components for modern clinical trials in radiation oncology. As radiation oncology planning computational platforms and clinical planning strategies become fully image driven, it is increasingly important to acquire and archive imaging objects that define radiation therapy (RT) treatment targets and evaluate response to treatment. Imaging and RT objects define study compliance and archiving these objects is necessary to validate study objectives and assess secondary questions not always anticipated at trial activation. This paper reviews problems and pitfalls associated with data acquisition from previous radiation oncology clinical trials and defines how critical acquiring, managing and archiving complete digital RT and Imaging data sets are for today’s trials.

Supporting Clinical Trials in Precision Medicine

The validity of an oncology clinical trial is strengthened with uniform treatment across the study population. Assuring treatment uniformity has been a focus for the quality assurance (QA) centers supporting the National Cancer Institute (NCI) for over three decades. During this time as oncology clinical trials have become more sophisticated, data acquisition, evaluation, and management have become more complex (1–4). With the launch of the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN), the NCI’s Cancer Clinical Trials Program was streamlined to maximize efficiencies in the era of precision medicine.

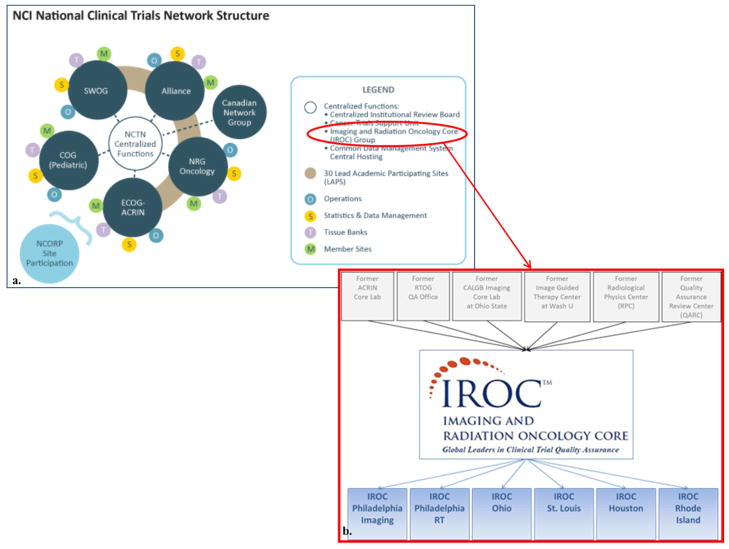

Previously, six separate organizations (Radiological Physics Center, American College of Radiology Imaging Network Corelab, Advanced Technology Consortium for Clinical Trials Quality Assurance, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group RT QA, Alliance Imaging Corelab, and the Quality Assurance Review Center (QARC)) monitored and ensured quality in trials with new imaging modalities and/or RT. Within the NCTN, these organizations have consolidated into the Imaging and Radiation Oncology Core Group (IROC) (Figure 1). Leveraging the IROC QA centers’ collective knowledge and experience, best practices are standardized to provide uniformly treated study populations that answer trial objectives. IROC services include site qualification and credentialing for imaging and RT; trial design support to promote clinical trials with clearly written imaging and RT guidelines and QA requirements; data management with uniform acquisition, assessment and archive processes; and case review (real time) for timely and efficient feedback to local sites and NCTN groups.

Figure 1.

a. IROC is within the NCTN Centralized Functions. Reprinted from The National Cancer Institute, 2015. (5) b. The IROC Core. Previous QA centers (top) that merged into IROC (bottom). Reprinted with permission from ASTROnews, 2014. (6)

Lessons Learned from Prior Protocol Performance

Imaging and Data Acquisition in Pediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma Radiotherapy Clinical Trials

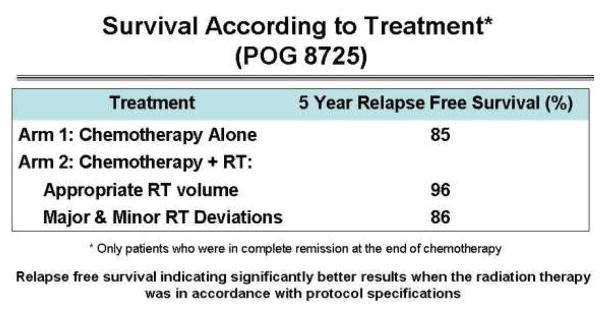

With the advent of computed tomography (CT), RT clinical trials began to use more advanced imaging tools for better target volume definition of treatment. Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) protocol 8725, an intermediate to high risk Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) study, had a treatment strategy of eight cycles of hybrid chemotherapy followed by RT to all sites of original disease defined on anatomic imaging including CT. The trial’s RT aspect was randomizing patients to treatment or no treatment. The original publication of the five year outcome analysis did not support the use of RT, with identical survival in both arms (7). A retrospective subset analysis of the imaging and RT data at QARC found that if patients were treated with protocol-compliant RT, patient survival was 10% higher than with the use of non-compliant RT (Figure 2). Study guidelines required the RT treatment fields to cover disease defined on imaging at presentation. Patients not treated according to study guidelines, as defined by excluding original disease from the RT fields, had an outcome identical to those treated with chemotherapy alone. The study RT deviation rate was nearly 30% and clearly influenced interpretation of the study in the primary analysis (4).

Figure 2.

POG 8725 Survival according to treatment- retrospective subset analysis. Reprinted with permission from Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2008 (4).

To reconcile the issue, this information was reviewed in committee by POG. A decision was made for the next generation of HL trials to require pre-treatment review of RT treatment objects to improve study compliance. Pre-treatment review assesses if the planned RT meets protocol guidelines and provides time for feedback to the investigator and enables modification before RT begins. Protocols 9425 and 9426 were developed that assessed chemotherapy and RT on intermediate and early stage HL patients respectively. The protocols included detailed descriptions of the RT treatment planning; delivery; and RT deviation descriptions; as well as imaging response descriptions. Institutions were required to submit treatment planning films and data along with baseline and post induction chemotherapy CT films prior to the start of RT. Institutions participated in the pre-treatment review at a rate of greater than 90% and the RT deviation (minor and major) rate dramatically decreased to fewer than 10%. Protocol 9426 also included a response-based treatment component. Limited-stage patients with complete response (CR) after two cycles of induction chemotherapy were treated with involved field RT (IFRT) to all sites of disease with no further chemotherapy. Patients with <CR received two additional cycles of chemotherapy prior to IFRT. A retrospective central review by the study diagnostic radiologist was performed using uniform criteria defined in the protocol. The agreement between local site review of response and central review was only 50% (8).

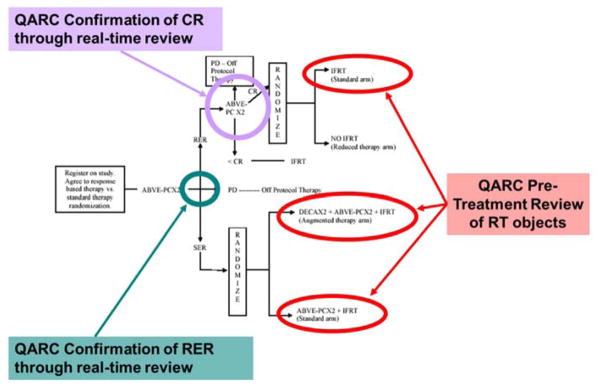

After the POG and the Children’s Cancer Study Group (CCG) merged to form the Children’s Oncology Group (COG), the next intermediate risk HL study was COG AHOD0031. This trial required multiple real time central reviews to assess chemotherapy response and pre-treatment review of RT treatment object compliance. The protocol defined the timeframe for data submission and assessment for each central review. After two chemotherapy cycles, QARC confirmed “rapid early responders (RER)” and “slow early responders (SER)” through central review. RER patients continued with two additional cycles of chemotherapy and through central review, QARC confirmed CR. Patients in CR were randomized between IFRT or reduced therapy without IFRT. Before beginning RT, RT treatment objects were reviewed in real time for protocol compliance (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Adapted from COG Protocol AHOD0031 schema displaying the real-time review assessment points. Central imaging reviews confirmed RER after two cycles of chemotherapy and CR after two additional cycles of chemotherapy. RT treatment objects were reviewed in real time prior to RT start. Reprinted from Front Oncol, 2013 (9).

The imaging and RT treatment data resided in a single informatics system. Synchronous online reviews were available to local and study investigators for resolution of local and central review discrepancies as needed. This process assured consistent interpretation of response and protocol compliant RT. The protocol accrued more than 1700 patients and became the benchmark for integrating imaging and RT in real time review for COG. This data acquisition and review platform is now used for all COG and many NCTN clinical trials including new protocols for early and advanced HL and HL in very young patients using abbreviated and adaptive treatment strategies. The informatics platform can be applied across all NCTN sites.

Through this work, an extensive library of imaging and information has been established and serves a resource for many academic projects. Recent papers reviewing the QA and patterns of failure on COG AHOD0031 have been published (10, 11). On review of the QA manuscript, the reviewers stated that it was clear that the resources required for quality review of RT objects were worth the effort because the data produced was secure and could be validated and believed.

Limited Data Acquisition in Adjuvant Therapy Breast Cancer Studies – Missed Opportunities

In spite of mechanisms to manage data and provide real time review of objects, many clinical trials do not take advantage of this strategy. Beginning in 1993, node positive breast cancer patients were treated in a series of protocols managed by the former Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) that validated Adriamycin and taxol and promoted dose-dense chemotherapy. These were pivotal trials in the development of chemotherapy for treating breast cancer. Because of the belief that RT did not influence survival for patients with breast cancer, information on local therapy was not collected. In 1997, papers were published that demonstrated the survival advantage for patients with node positive breast cancer treated with local and/or regional RT (12, 13). CALGB 9741 was one of the trials where no analysis of the influence of RT was performed. An effort was made by Carolyn Sartor and colleagues at QARC to see if the RT treatment of these patients could be acquired retrospectively and determine if this would have influenced trial outcome. This retrospective data collection became a difficult challenge. As this data collection was not part of the original protocol design, many institutions required completion of a separate consent form to acquire the patient RT information. Therefore only a limited amount of RT information was acquired constituting about 33% of patients on study. A publication of this effort revealed a tendency for patients who received taxol to also undergo RT, possibly obfuscating trial results of the role of taxol (14).

If RT/imaging guidelines and data requirements had been incorporated in these important studies, failure patterns could have been volumetrically assessed. These patterns would have influenced and likely improved target definition for future trials. A comprehensive database of the RT objects and imaging would have provided a platform to evaluate normal tissue damage and help develop dose volume constraints to important targets including brachial plexus, large vessels, and chest wall. If RT data/imaging (including relapse imaging) acquisition guidelines are not incorporated into the initial trial document, it is exceptionally difficult, if not impossible, to retrospectively acquire information. This is important for imaging and unanticipated study outcome(s).

Recent clinical trials evaluating more limited axillary staging in breast cancer provide further evidence that comprehensive imaging acquisition guidelines are needed. Z0011 was an important clinical trial managed by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG). This trial demonstrated that more limited axillary surgery was efficacious and tangential RT was appropriate in patients with limited nodal involvement. Although there were limited guidelines for adjuvant RT, there was no central review of the dose and volume during the trial. After the primary paper was published, efforts were made by Reshma Jagsi and colleagues at QARC to review the RT information. They encountered similar challenges as Carolyn Sartor in acquiring information retrospectively. Information they did acquire demonstrated a significant number of study patients were treated with regional RT rather than the protocol intended volume (15). This further complicates strategies for future studies as the role of limited regional RT in breast cancer care remains ambiguous. If imaging and RT information had been acquired on-study, including relapse imaging, defining axillary volume for current NCTN studies would be based on more secure evidence.

One argument in limiting data acquisition in RT clinical trials is cost. This argument is often short sighted and does not reflect what is needed to move the field forward. The cost associated with clinical trials data management is in the establishment of the QA infrastructure. Once in place, this infrastructure provides a great dividend in developing an archive which can be re-purposed to answer questions not anticipated at the time of trial development. Targeting regional volumes in breast cancer would be much better defined if data was collected on studies that accrued thousands of patients. One salient point about clinical trials is that often questions needing to be asked become evident only when results are gathered and reported, rather than at trial design. The library of imaging and information can support secondary review activities to extract ancillary information when primary trial results suggest a more thorough review of imaging/RT objects might provide additional insights via subset analysis.

The Need for Real Time Review of Objects for Clinical Trial Management

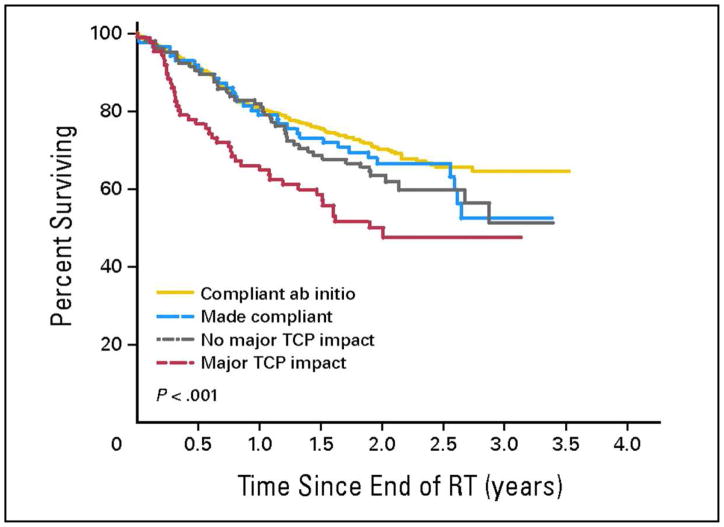

The HeadSTART phase 3 clinical trial was conducted by the Trans Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG) and Sanofi-Aventis to evaluate the role of tirapazamine (TPZ) in locally advanced (stage 3 and 4) squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. This study was built on favorable TROG phase 2 data, supporting the use of TPZ as a hypoxia-selective antitumor agent to potentiate radiation. The HeadSTART trial was conducted internationally, across 16 countries, to facilitate accrual, unlike the phase 2 trial which enrolled patients from one institution. A credentialing mechanism was used for trial participation and complete RT treatment records were collected at QARC. The Trial Management Committee (TMC) determined that the real-time review of treatment objects would occur during the first three days of treatment due in part to international participation. QARC reviewed RT treatment plans with immediate feedback to local investigators. Of the 816 patients on study, requests for readjustments were made on 211 treatment plans as part of on treatment review. Ninety-five plans were adjusted by local investigators and deemed study compliant at final review by the TMC. Adjustments were not made on 116 plans and only five plans were thought to be compliant at final review. As identified in the primary publication, the deviations on study confounded trial results and likely influenced trial outcome indicating no clear benefit to the use of TPZ in spite of favorable phase 2 data. The TMC asked QARC to perform a more detailed evaluation of study deviations, specifically to define whether the deviation had clinical significance including gross tumor identified on imaging not receiving protocol compliant dose. As seen in Figure 4, patients with compliant plans de novo had optimal survival. If a plan was adjusted to meet study guidelines after initiation of treatment, patient survival was good but not as good as a compliant plan de novo. If the deviation was not thought to be clinically significant (gross tumor covered by protocol dose), patient survival was also similar to the patients whose plans were adjusted to meet study guidelines. If the deviations were considered clinically significant, patient survival was approximately 30% less than patients with compliant plans (16).

Figure 4.

Overall survival by deviation status in the TROG 02.02 HeadSTART trial: (1) compliant from outset (n = 502), (2) made compliant following QARC review (n = 86), (3) noncompliant but without predicted major adverse impact on tumor control (n = 105), and (4) noncompliant with predicted major adverse impact on tumor control (n = 87). Overall P < .001. Pair-wise tests: not statistically significant except for cohort 1 versus cohort 4 (P < .001), cohort 2 versus cohort 4 (P = .041), and cohort 3 versus cohort 4 (P = .006). TCP, tumor control probability; RT, radiotherapy. Reprinted with permission from J Clin Oncol, 2010. (16)

This landmark study demonstrated many important lessons for the need of QA. RT was not the study question; however lack of compliance to RT protocol guidelines influenced study performance. This trial required international participation and as such, application of imaging objects to RT treatment fields was varied and inconsistent with study strategy in approximately 25% of the patients. There was also evidence that centers enrolling fewer than five patients had a higher non-compliance rate. Although there are alternative explanations to the HeadSTART trial outcome, the phase 2 data suggested the phase 3 trial would be positive. In this phase 3 study, the deviations may have overridden study objectives and influenced study outcome. Moving forward, studies must avoid this.

Importance of Diagnostic Imaging Validation in RT QA

A secondary analysis of RTOG 0617, a phase III randomized trial comparing 60 Gy to 74 Gy in patients with inoperable Stage III non-small cell lung cancer, showed that patients treated at centers enrolling a higher volume of patients on this trial had a six month median survival improvement compared to patients treated at centers enrolling lower volumes. This suggests as noted above in the HN trial, experience in treatment and compliance to protocol make a difference (17). Patients included in this analysis all had protocol compliant treatment plans. However, pre-treatment PET or PET/CT imaging was not submitted for review. Collection and review of pre-treatment PET or PET/CT imaging would have been helpful to identify why a discrepancy in treatment outcome exists between patients treated at high-volume versus low-volume centers. As clinical trials are developed to study subsets of patient populations in specific disease sites, each patient on study is crucial for evaluation.

COG medulloblastoma trial, A9961, had 15% of patients with equivocal evidence due to imaging quality and inability to assess presence or absence of metastatic disease or postoperative residual disease in the posterior fossa (18). It is not clear if these unevaluable patients affected study outcome, but based on previous data mentioned above, there is a high likelihood for some influence. Protocols in the future can no longer support such a degree of ineligibility, especially in adaptive clinical trials for diseases with multiple disease subsets.

The Role of Quality Assurance

The IROC QA centers are responsible for supporting the NCTN in protocol development and data management for imaging and RT aspects in clinical trials (Figure 5). IROC provides credentialing services and the capability of supporting real time review of objects as needed for success of each trial working in close collaboration with the NCTN groups and local/study investigators. The purpose of QA is to ensure high quality data by assuring trial objectives can be met. The QA process should provide confidence that the trial outcome can be directly applied to clinical practice. It is not the intent of QA to directly influence study outcome. However, as demonstrated in the recent paper by Fairchild and colleagues, QA favorably influenced clinical trial performance with possible direct influence in outcome in nearly 50% of trials (19). Several important aspects of the QA process impact this finding. Credentialing insures institutions have the infrastructure to participate in the specific trial. QA centers have data management systems to insure that data can be received and reviewed in a timely manner and archived for potential future needs. Central image review and review of the application of RT objects insures compliance. As has been demonstrated, this is significantly important in trials where key RT questions are under review including new technologies, dose escalation/de-escalation, and attenuated/adaptive target volume.

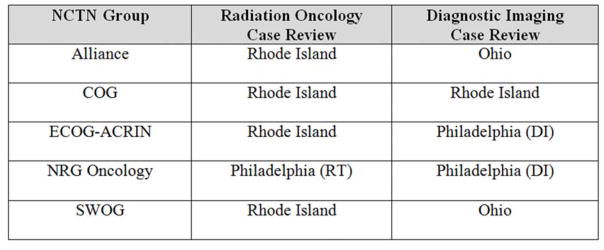

Figure 5.

IROC Centers and Case Review in the NCTN. IROC Houston plays an essential role in providing credentialing services for participating RT sites in NCTN trials.

A Best Practice Goal for NCTN Trials

Protocol and individual case review systems provided by IROC can include many of the following strategies:

Perform pre-treatment real time review on a selected number of cases submitted by each participating site. Real time review can be done on each case in selected protocols as needed.

Institutions correct problems found by step 1, and IROC documents common performance issues.

IROC helps prepare early protocol amendments to address issues that indicate lack of understanding of protocol details.

IROC and clinical trials group closely follow results of post-treatment reviews to determine compliance rate and modify real time review process as needed.

Site Qualification and Credentialing strategies will continue to be an important component in Imaging/RT QA. These strategies assure a local site has the requisite expertise to perform the protocol as well as familiarizing site personnel with new protocol requirements. As trials move to include more international participation, potentially introducing more practice variability, a strong credentialing program is critical. Additionally, trials will include harmonized RT QA naming conventions to facilitate data sharing (20).

These QA strategies are nimble, facile and have not been a barrier to accrual. It is recognized that QA processes will be applied differently based on the specific needs of each trial.

As precision medicine trials continue to emerge and smaller subsets of patients are studied, the need for quality data is pre-eminent. It is important to optimize resources in the QA process while not losing the opportunity to build the archive for critical future investigations (21). NCTN clinical trials are the primary vehicle to define new and evolving treatment standards of care for cancer patients. The role of high quality Imaging and RT QA cannot be minimized in producing high quality data to answer today’s critical cancer treatment questions.

Acknowledgments

NIH/NCI U24 CA180803

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest, copyrights, permissions

The authors have completed the Uniform Disclosures form, patient photos are not being used, and copyright permissions are attached.

These authors contributed to this manuscript in their personal capacities and the opinions expressed herein may not reflect the official position of the NIH or DHHS.

Contributor Information

Thomas J. FitzGerald, UMass Memorial Medical Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School, IROC Rhode Island.

Maryann Bishop-Jodoin, University of Massachusetts Medical School, IROC Rhode Island.

David S. Followill, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, IROC Houston.

James Galvin, Thomas Jefferson University, IROC Philadelphia (RT).

Michael V. Knopp, Wexner Medical Center, Ohio State University, IROC Ohio.

Jeff M. Michalski, Washington University School of Medicine, IROC St. Louis.

Mark A. Rosen, University of Pennsylvania Health System, IROC Philadelphia (DI).

Jeffrey D Bradley, Washington University School of Medicine.

Lalitha K. Shankar, National Cancer Institute.

Fran Laurie, University of Massachusetts Medical School, IROC Rhode Island.

M. Giulia Cicchetti, UMass Memorial Medical Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School, IROC Rhode Island.

Janaki Moni, UMass Memorial Medical Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School, IROC Rhode Island.

C. Norman Coleman, National Cancer Institute.

James A. Deye, National Cancer Institute.

Jacek Capala, National Cancer Institute.

Bhadrasain Vikram, National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Glicksman AS, Reinstein LE, McShan D, et al. Radiotherapy quality assurance program in a cooperative group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7:1561–1568. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(81)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glicksman AS, Wasserman TH, Bjarngard B, et al. The structure for a radiation oncology protocol. The Committee of Radiation Oncology Group Chairmen. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:1079–1082. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90916-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donaldson SS, Torrey M, Link MP, et al. A multidisciplinary study investigating radiotherapy in Ewing’s sarcoma: end results of POG #8346. Pediatric Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:125–135. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.FitzGerald TJ, Urie M, Ulin K, et al. Processes for quality improvements in radiation oncology clinical trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(Suppl 1):S76–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The National Cancer Institute. [Accessed September 24, 2015];Infographics from NCI: NCI National Clinical Trials Network Structure. http://www.cancer.gov/PublishedContent/Images/research/areas/clinical-trials/nctn/nctn-clinical-trials-network.png. Updated May 29, 2015.

- 6.FitzGerald TJ, Followill DS, Galvin J, et al. Restructure of clinical trial system addresses evolving needs. ASTROnews. 2014;17:18–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner MA, Leventhal B, Brecher ML, et al. Randomized study of intensive MOPP-ABVD with or without low-dose total-nodal radiation therapy in the treatment of stages IIB, IIIA2, IIIB, and IV Hodgkin’s disease in pediatric patients: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2769–2779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.8.2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendenhall NP, Meyer J, Williams J, et al. The impact of central quality assurance review prior to radiation therapy on protocol compliance: POG 9426, a trial in pediatric Hodgkin’s disease [Abstract] Blood. 2005;106:753. [Google Scholar]

- 9.FitzGerald TJ, Bishop-Jodoin M, Bosch WR, et al. Future vision for the quality assurance of oncology clinical trials. Front Oncol. 2013;3:31. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dharmarajan KV, Friedman DL, FitzGerald TJ, et al. Radiotherapy quality assurance report from Children’s Oncology Group AHOD0031. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91:1065–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dharmarajan KV, Friedman DL, Schwartz CL, et al. Patterns of relapse from a phase 3 study of response-based therapy for intermediate-risk Hodgkin lymphoma (AHOD0031): a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ragaz J, Jackson S, Le N, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in node-positive premenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:956–962. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overgaard M, Hansen PS, Overgaard J, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk premenopausal women with breast cancer who receive adjuvant chemotherapy: Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group 82b Trial. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:949–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sartor CI, Peterson BL, Woolf S, et al. Effect of addition of adjuvant paclitaxel on radiotherapy delivery and locoregional control of node-positive breast cancer: cancer and leukemia group B 9344. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:30–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagsi R, Chadha M, Moni J, et al. Radiation field design in the ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3600–3606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters LJ, O’Sullivan B, Giralt J, et al. Critical impact of radiotherapy protocol compliance and quality in the treatment of advanced head and neck cancer: Results from TROG 02.02. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2996–3001. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eaton BR, Pugh SL, Bradley JD, et al. The effect of institutional clinical trial enrollment volume on survival of patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiation: A report of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 0617 [Abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(Suppl 5s):7551. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Packer RJ, Gajjar A, Vezina G, et al. Phase III study of craniospinal radiation therapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4202–4208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairchild A, Straube W, Laurie F, et al. Does quality of radiation therapy predict outcomes of multicenter cooperative group trials? A literature review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87:246–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melidis C, Bosch WR, Izewska J, et al. Global harmonization of quality assurance naming conventions in radiation therapy clinical trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90:1242–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.08.348. Erratum in: Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2015, 91, 1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bekelman JE, Deye JA, Vikram B, et al. Redesigning radiotherapy quality assurance: opportunities to develop an efficient, evidence-based system to support clinical trials--report of the National Cancer Institute Work Group on Radiotherapy Quality Assurance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]