Abstract

Half the population of low- and middle-income countries will live in urban areas by 2030, and poverty and inequality in these contexts is rising. Slum dwelling is one way in which to conceptualize and characterize urban deprivation but there are many definitions of what constitutes a slum. This paper presents four different slum definitions used in India alone, demonstrating that assessments of both the distribution and extent of urban deprivation depends on the way in which it is characterized, as does slum dwelling’s association with common child health indicators. Using data from India’s National Family and Health Survey from 2005–2006, two indictors of slum dwelling embedded in the survey and two constructed from the household questionnaire are compared using descriptive statistics and linear regression models of height- and weight-for-age z-scores. The results highlight a tension between international and local slum definitions, and underscore the importance of improving empirical representations of the dynamism of slum and city residents.

INTRODUCTION

Background

More than half of the world’s population lives in urban areas and by 2030 it is projected that over half of residents in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) will reside in cities (Montgomery, 2008). As rural residents move to urban areas in search of jobs and villages are overtaken by expanding urban agglomerations, many low- and middle-income countries are increasingly concerned with the urbanization of poverty (Pradhan, 2012). The rapid and large scale of urban growth has raced far ahead of the provision of services (Yach et al., 1990) and has precipitated a proliferation of informal settlements – and the development of new, smaller cities (Montgomery, 2009) – without access to water and sanitation, garbage collection or security of tenure.

Concentrated urban poverty and deprivation is often characterized by residential crowding, exposure to environmental hazards, and social fragmentation and exclusion (Wratten, 1995), all components of a cluster of conditions frequently referred to with the catch-all term of “slum dwelling”. Indeed, policy and media rhetoric on urban issues tends to focus on slums because of their intuitive appeal and relatively natural conceptual summarization of what constitutes concentrated deprivation in urban areas.

The word “slum” was first used in London at the beginning of the 19th century to describe a “room of low repute” or “low, unfrequented parts of the town”, but has since undergone many iterations in meaning and application (UN-HABITAT, 2003b). While early definitions of slum dwelling combined physical, spatial, social and even behavioral aspects of urban poverty (UN-HABITAT, 2003a), the spread of associations has more recently narrowed. Indeed, a slum has been re-defined by the United Nations Program on Human Settlements (UN-HABITAT) as “a contiguous settlement where the inhabitants are characterized as having inadequate housing and basic services. A slum is often not recognized and addressed by the public authorities as an integral or equal part of the city” (UN-HABITAT Urban Secretariat & Shelter Branch, 2002). The United Nations (UN) even incorporated slums into the Millennium Development Goals as part of Goal 7, to Ensure Environmental Sustainability: target 7.D is to “Achieve, by 2020, a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers” (United Nations, 2013), putting area-level deprivation and urban poverty on the development agenda.

In the most recent report on progress towards the MDGs it was found that Target 7.D had been met (United Nations, 2013), and international and multilateral attention has subsequently turned elsewhere. There are a number of concerns regarding this optimistic assessment, however. First, it is not clear that achieving this goal is the significant accomplishment the UN is touting it to be because the goal was most likely developed based on an underestimation of the worldwide slum population, making it significantly less aspirational than it may appear to be. Additionally, unlike other targets, 7.D is an absolute number, not a proportion, meaning that it can be met even as slum populations continue to grow in absolute size. This has indeed taken place; the UN estimates there were 650 million slum dwellers in 1990; this number grew to 760 million in 2000 and 863 million in 2012. The most important issue with the UN’s finding that target 7.D has been reached, however, is the challenge of establishing, in practice, what actually constitutes a slum.

Slum definition

The definition of what constitutes a slum, like that which constitutes an urban area more generally (Dorélien et al., 2013), differs by country (United Nations, 2014), state (Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, 2008) and even city (O’Hare et al., 1998). Recent research has also indicated that slums may be more heterogeneous than is often assumed (Goli et al., 2011, Chandrasekhar and Montgomery, 2009, Agarwal and Taneja, 2005); many poor people like pavement dwellers do not live in slums and are therefore not “counted” by the standard definitions (Agarwal, 2011).

The UN operationally defines a slum as “one or a group of individuals living under the same roof in an urban area, lacking in one or more of the following five amenities”: 1) Durable housing (a permanent structure providing protection from extreme climatic conditions); 2) Sufficient living area (no more than three people sharing a room); 3) Access to improved water (water that is sufficient, affordable, and can be obtained without extreme effort); 4) Access to improved sanitation facilities (a private toilet, or a public one shared with a reasonable number of people); and 5) Secure tenure (de facto or de jure secure tenure status and protection against forced eviction) (UN-HABITAT, 2006/7).

While this definition of what constitutes a slum was used by the UN to evaluate whether target 7.D had been met, it is quite different than those which are used by individual countries for their own policy and planning purposes. Uganda, for example, in a document outlining a slum upgrading strategy and action plan from 2008, defines slums as having one or more of the following attributes: 1) Attracting a high density of low income earners and/or unemployed persons with low levels of literacy, 2) An area with high rates/levels of noise, crime, drug abuse, immorality (pornography and prostitution) and alcoholism and high HIV/AIDS prevalence, or 3) An area where houses are in environmentally fragile lands, e.g. wetlands (Ministry of Lands, 2008). Applying the UN’s slum definition to Ugandan cities results in 93% of the urban population living in slums.

In India, notification, or legal designation, as a slum settlement is central to the recognition of slums by the government and over time is intended to afford residents rights to the provision of potable water and sanitation. But many communities exhibiting distinctly slum-like characteristics are never notified (Subbaraman et al., 2012); Delhi, for example, has notified no new slums since 1994 (Bhan, 2013). The UN definition incorporates legality, however, and would presumably identify all deprived areas, and not just those recognized as slums by the government, likely leading to disagreement over the distribution and absolute number of slum residents in India.

These differences, as well as the absolute nature of MDG target 7.D, can lead to divergent priorities between the international community and local governments, complicating the assertion that target 7.D has been met and that this development agenda item should be put aside. The tension between multilateral and country-level definitions of what constitutes a slum precipitates the central research question of this paper: does it matter how slums are defined? In other words, do different definitions simply tap into the same underlying construct of concentrated urban deprivation and identify the same areas as slum dwelling? This paper will investigate slum dwelling in one context in particular – that of India – for the following reasons:

The definition and identification of slums is of current policy and programmatic importance to the Government of India, which is increasingly concerned with growing poverty, inequality and poor health among its 400 million urban residents. The Indian government has developed policy initiatives such as the Rajiv Awas Yojana, which envisages a “slum free India” (Ministry of Urban Housing and Poverty Alleviation, 2010) and may benefit from further guidance regarding documentation and measurement of the distribution and extent of its urban poor population.

Urbanization in India, like any widespread phenomenon in a country of over a billion people, is a massive planning and policy challenge. After economic liberalization in the early 1990s, India’s urban population grew by almost 32% in a decade (Agarwal et al., 2007). The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that by 2030 about 590 million Indians will live in cities, which is almost twice the US population today (Sankhe et al., 2010); the UN projects that by 2030 the country will be majority urban. The study of urban phenomena in India is therefore large in both absolute size and importance.

Relatedly, India’s cities have been called the engine of the country’s growth and development. But poor living conditions like those found in slums likely have consequences for productivity and human capital development. Slum residents have been found to pour immense time and resources into obtaining water and waiting to use public toilets, for example, which has severe economic and even mental health consequences (Subbaraman et al., 2014). Lack of infrastructure and security in slums may reduce residents’ involvement in the labor force and their participation in society, both of which may exact a toll on the country’s development trajectory.

The National Family and Health Survey (NFHS), India’s Demographic and Health Survey, from 2005–2006, includes information from both the Census and the survey enumerators regarding whether the household is located in a slum area, allowing for the comparison of slum definitions and their association with indicators of wellbeing. Population-based sampling frames drawn from Census for nationally representative surveys like the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) are almost never stratified by slum status (Montana et al., forthcoming) and the inclusion of these data in the most recent NFHS makes the comparison of multiple definitions of slum dwelling in the Indian context possible.

There are a number of empirical studies that have worked with the two definitions of slum dwelling included in the NFHS. Swaminathan and Mukherji find that the association between slum dwelling and under- and overweight among adults in eight urban areas in India yielded different results both in terms of significance and magnitude depending on the definition used (Swaminathan and Mukherji, 2012). Dev and Balk combine the two definitions, identifying households as residing in slums when they met either of two criteria (Dev and Balk, under review). Most other researchers have simply chosen to focus on the Census (Gaur et al., 2013, Hazarika, 2010) or the NFHS (Rooban et al., 2012) definitions exclusively, however, with little justification. But the slum definitions embedded in the NFHS are not the only manner in which to empirically characterize slum dwelling. Günther and Harttgen use survey respondents’ reported characteristics of their household and its surroundings to characterize families as living in a slum or not in Sub-Saharan Africa (Günther and Harttgen, 2012), and Fink and colleagues employ a similar methodology across 73 countries to compare the health of rural, urban and slum residents (Fink et al., 2014). This paper unifies these different definitional approaches by comparing four definitions of slum dwelling – two already embedded in the NFHS questionnaire, and two constructed from respondent’s reports about their surroundings – to characterize intra-urban inequality and its implications in urban India.

Identifying, comparing, and assessing definitions of what constitutes slum dwelling is not only important from an urban planning and agenda-setting perspective, but also because of the significant literature documenting the effect of area-level poverty on health, much of which is based in the urban Indian context (Agarwal, 2011).

Urban Deprivation, Slums, and Health

Although the mechanisms – social interactive, environmental, geographic, or institutional, just to name a few (Galster, 2010) – by which community-level poverty may be associated with poor health outcomes are still under investigation, poor health in slum areas has been found mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa (Bocquier et al., 2011, Günther and Harttgen, 2012) and South Asia, particularly Bangladesh (Gruebner et al., 2011) and India (Gaur et al., 2013, Hazarika, 2010). Close living quarters, poor sanitation, and lack of access to potable water (Sclar et al., 2005), all characteristics of “slum-like” communities, are likely to produce poor health over and above the effects of simply living in a poor household and other individual-level characteristics (Rice and Rice, 2009). Crowding, for example, tends to promote the transmission of infectious diseases like pneumonia, diarrhea, and tuberculosis (Unger and Riley, 2007) and neighbors’ open defecation has been found to be negatively associated with child height (Spears, 2013).

These health challenges are exacerbated by the illegality and social exclusion experienced in slum settlements (de Snyder et al., 2011, Subbaraman et al., 2012), poorly regulated and ineffective health services (Agarwal et al., 2007), exposure to environmental hazards (Unger and Riley, 2007), and a lack of clarity regarding which level of the Indian Government (local, State, etc.) is responsible for protecting and promoting the health of the poorest urban residents (Nolan et al., 2014). Taken together, the possibility of an “urban mortality penalty”, such as that which occurred during industrialization in European and American cities in the 20th century, is not unlikely (Konteh, 2009).

In order to investigate the implications of slum dwelling, this paper will focus on one indicator of human and economic wellbeing, that of child health (Strauss and Thomas, 1998). We use child height to investigate the effects of past epidemiological and nutritional environment (Deaton, 2007), and weight to look more at acute and current health, and nutritional stressors. About half of India’s children are undernourished, and lower height for age in particular has been associated with reduced cognitive and educational achievement (Hoddinott et al., 2011) as well as lower wages and labor market productivity over the life course (Case and Paxson, 2008). Evidence from India indicates that economic growth has not brought about improved child nutrition (Deaton and Dréze, 2009) and almost half of children under five are stunted (UNICEF, 2013). Undernutrition not only directly affects children’s physical and cognitive growth, but it is also implicated in deaths from infectious diseases such as malaria, pneumonia and measles, making the underlying condition responsible for over 20 percent of the country’s burden of disease (Gragnolati et al., 2005).

Most studies of the health of slum dwellers investigate this topic within one slum in particular (Subbaraman et al., 2013), in one city (Fotso et al., 2013, More et al., 2013) or across many countries employing a standardized definition of what constitutes slum dwelling (Fink et al., 2014). While one paper by Montgomery and Hewett investigated neighborhood socio-economic status’ effect on height for age (Montgomery and Hewett, 2005) using the NFHS, the association between slum dwelling and child height and weight has, to the author’s knowledge, not yet been systematically investigated in the Indian context.

DATA AND METHODS

Data

This study uses data from the third wave of India’s National Family and Health Survey (NFHS), collected in 2005–2006, the first and only demographic and health survey to include multiple measures of slum designation at the primary sampling unit (PSU) level. Slum designation is only available for eight cities, however: Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Indore, Kolkata, Meerut, Mumbai, and Nagpur (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International, 2007). While the NFHS is a nationally representative repeated cross sectional survey of demographic and health indicators, the analyses presented here use only data from these eight cities, which are relatively well distributed around the country as shown in Figure 1, in order to take advantage of their inclusion of multiple definitions of slum designation. This allows for comparison across four different slum definitions; two embedded in the individual-level data as factor variables and two constructed from the household questionnaire. The four definitions are described extensively in Tables 1 and 2. By way of summary, the “Census” definition emphasizes legality, the “NFHS” definition is based on survey enumerator observation, the “UN” definition is comprised of universally recognized components of a healthy environment (UN-HABITAT, 2006/7) and the “Committee” definition has been tailored to the Indian context as recommended for the 2011 Census in a Report to the Committee on Slum Statistics/Census (Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, 2008).

FIGURE 1.

Map of eight cities in India where data include slum designation

TABLE 1.

Origin and emphases of slum definitions

| Name | Origin | Empirical generation | Legality | Density | Housing | Water | Sanitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census | 2001 Census of India | Variable included in the NFHS-3 | X | X | X | X | X |

| NFHS | Survey enumerator observation | Variable included in the NFHS-3 | X | X | X | X | |

| UN | Household questionnaire | Aggregated to the primary sampling unit level | X | X | X | X | |

| Committee | Household questionnaire | Aggregated to the primary sampling unit level | X | X | X |

TABLE 2.

Slum definitions in detail

| Characteristic | Census | NFHS | UN – at least one or more | Committee – all four |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legality |

|

NAi | NAii | NA |

| Density | A compact area of at least 300 population or about 60–70 households | A compact area of at least 300 population or about 60–70 households | Insufficient living areaiii | NA |

| House | Poorly built congested tenements in unhygienic environment usually with inadequate infrastructure | Poorly built congested tenements in unhygienic environment usually with inadequate infrastructure | Non-durable housing;iv lack of a permanent structure providing protection from extreme climate conditions | Predominant material of roof is anything other than concrete |

| Water | Lacking proper drinking water facilities | Lacking proper drinking water facilities | Lack of access to improved waterv that is sufficient, affordable, and attained without extreme effort | Available drinking water source not be available within the premisesvi |

| Sanitation | Lacking in proper sanitary facilities | Lacking in proper sanitary facilities | Lack of access to improved sanitation facilitiesvii | Household does not have an latrine facility within the premises (e.g. members use either a public latrine or no latrine) and does not have closed drainageviii |

The Census and NFHS dummy variables (0 - not slum; 1- slum) are embedded in the individual-level questionnaire at the primary sampling unit (PSU) level, which suffices as a proxy for the neighborhood in which respondents live. In rural areas, PSUs are villages. In urban areas, the NFHS uses a slightly more complex procedure: Wards were first selected systematically from the 2001 Census and then one census enumeration block of about 150–200 households was selected from each ward (both selections were done with probability proportional to size). A household listing was done for each enumeration block and on average, 30 households were targeted for interview, with a minimum and maximum of about 15 and 50 households, respectively. The NFHS data are not geo-referenced and there is no other manner in which to operationalize spatial proximity (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International, 2007). There are 597 PSUs in the eight cities that have non-missing values for the four slum designations included in these analyses.

The UN and Committee definitions are built from the household questionnaire and based on reports of family’s living circumstances. First, each of the four indicators for the UN definition (lack of access to improved water, improved sanitation, sufficient living area, and durable housing) were coded 1 if the household displayed the slum-related deprivation and 0 if not. When summed, households with a score of 1 or more were designated as slum-like:

Where di UN indicates deprivations i = 1 through 4 from the UN definition. This analytical operationalization differs slightly from that which is employed by Fink and colleagues (2014) who found that defining slum dwelling in this manner across 74 different countries resulted in an “implausible” proportion of households living in slums. This prompted the authors to use a more stringent coding of slum dwelling, defined as a household experiencing two or more of the four deprivations (Fink et al., 2014), reducing substantially the proportion living in slums. The objective of the current paper is to operationalize as faithfully as possible the four different slum definitions, however, and for this reason households were designated as slum-like if they exhibited only one of the four deprivations as indicated by the UN definition. A similar approach was taken for the Committee definition: each of the three indicators (non-concrete roofing material, no drinking water facility on the premises, and use of public or no latrine) were coded as 0/1 and summed. Households with a score of 3 were designated as slum-like; the definition required the household to display all three characteristics:

Where di committee indicates deprivations i = 1 through 3 from the Committee definition.

Finally, in order to make a fair unit-wise comparison across all four definitions and for consistency in the conceptualization of slum dwelling as a community-level phenomenon, the two definitions constructed from the household survey – the UN and Committee definitions – were aggregated to the PSU level as the proportion of surveyed households in that PSU characterized as “slum-like” by each definition, respectively. PSUs are defined as slums by the UN and Committee definitions if over 50 percent of the households interviewed exhibited “slum-like” characteristics. This cutoff has been used previously for the UN definition (Günther and Harttgen, 2012), although Fink and colleagues again used a more stringent approach given their focus on cross-country assessment of the urban advantage in child health, rather than an accurate operationalization of slum dwelling in any particular context.

The dependent variables are height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores of children under 5 years old, scaled to the World Health Organization’s reference chart and excluding children with questionable scores of under −6 and over 6 as is standard practice. We do not investigate stunting or wasting – dichotomous variables defined as two or more standard deviations below the median of the reference population – to preserve power, as has been recommended in the literature (Spears, 2013). We also neither investigate mortality given the relatively small sample size, nor child morbidity given concerns about the accuracy of self-reported health diagnoses.

Independent variables included in the regressions are all well known to be associated with both poor child health and poverty in the Indian context. Child characteristics include child’s sex, multiple births, and child’s size at birth. It is well known that son preference remains prevalent in India (Deaton, 2008), and has been shown to manifest itself in discrimination against women and girls (Ramalingaswami et al., 1996); poorer nutrition and neglect can lead to lower height for age. Being one of multiple births is also controlled for in the multivariate models; birth weight is related to later height, health and development outcomes (Currie and Vogl, 2013).

Mothers’ characteristics include her education, religion, number of children ever born, whether she works outside the home, her height, her caste and her migration status. The effect of mothers’ education on the health and wellbeing of her children is one of the most robust, consistent and generalizeable findings in the development literature (Lutz and KC, 2011). Education is related to maternal health and height attainment as well as increased human capital and productivity (Strauss and Thomas, 1998). High levels of childbearing take a toll on women’s health and is associated with poorer health and greater stress, leading to lower birth weight babies (Cleland et al., 2006). Recent work in an urban demographic surveillance site in Nairobi City, Kenya found that working outside the home was associated with child morbidity (Taffa et al., 2005). Being a member of a “backward” or scheduled caste or tribe in India is a marker of historic experiences of marginalization and deprivation, which may significantly influence current health and development outcomes and future trajectories (Gragnolati et al., 2005). Being a Muslim versus a Hindu may also indicate underprivileged. Finally, a large literature on migration status and health in indicates that the children of recent migrants have worse health outcomes and higher odds of dying than non-migrants (Brockerhoff, 1995), findings that have been replicated in India (Stephenson et al., 2003).

Other control variables include husband/father’s education, a fixed effect for the eight cities in which the data were collected, and a household wealth score. Fathers’ education is associated with higher standards of living and presumably a healthier nutritional and epidemiological environment, although the effect found in the literature is nowhere near the size of that for maternal education. Indeed, women are thought to invest additional available resources more heavily in their household’s wellbeing than their male counterparts (Duflo, 2012). City fixed effects are included to control for characteristics of each city to which all respondents living in that city were exposed, and to account for the uneven distribution of health status across urban areas in the sample under study. Table 3 presents summary statistics for all control variables included in the models.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | Proportion, or mean (sd) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Height for age | −1.49(1.65) | |

| Weight for age | −1.38(1.21) | ||

| Sex | Male | 52.8 | |

| Female | 47.2 | ||

| Multiple birth | Yes | 1.2 | |

| No | 98.8 | ||

| Size at birth | Small | 14.2 | |

| Medium | 63.4 | ||

| Large | 22.4 | ||

| Mother | Education | None | 22.7 |

| Primary | 10.8 | ||

| Secondary | 48.4 | ||

| Higher | 18.1 | ||

| Religion | Hindu | 72.1 | |

| Muslim | 24.5 | ||

| Other | 3.4 | ||

| Children born in the last 5 years | 1.5(0.64) | ||

| Age | 26.8(4.59) | ||

| Height | 152.5(5.86) | ||

| Working | Yes | 82.7 | |

| No | 17.3 | ||

| Scheduled caste or tribe | Yes | 20.8 | |

| No | 79.2 | ||

| Migrant | Yes – from a rural area | 29.5 | |

| Yes – from anurban area | 43.7 | ||

| No | 26.8 | ||

| Mothers’ partner | Education | None | 13.4 |

| Primary | 11.3 | ||

| Secondary | 54.1 | ||

| Higher | 21.2 |

Finally, a wealth score was constructed using the first principle component (Filmer and Pritchett, 2001) of a factor analysis of 19 household assets indicative of socioeconomic status in an urban area in India. These include: radio, television, refrigerator, bicycle, motorcycle/scooter, car, modern cooking fuel, mobile phone, watch, mattress, pressure cooker, chair, cot/bed, table, electric fan, sewing machine, computer, water pump. About 96 percent of the analytical sample reported having electricity, so these items are both relevant and usable in the urban Indian context. Items like tractor, livestock and irrigated land were excluded because they were unlikely to indicate socioeconomic status in an urban setting. Modern cooking fuel was designated as 1 for electricity, lpg/natural gas and biofuel, and 0 for kerosene, coal, lignate, charcoal, wood, straw/shrubs/grass, agricultural crop, animal dung. The score produced from the principle components analysis was not broken into quintiles because its cumulative distribution is not linear, but is used as a continuous variable in all regressions.

Methods

The final analytical sample of children with no missing data on the dependent or any of the independent variables consisted of 4,609 children under the age of 5 years. The four definitions are first compared descriptively and then their association with child health is assessed beginning with bivariate regressions of each slum definition on each health outcome. These were followed by a second step of ordinary least squares models containing all independent variables (Fink et al., 2012):

Where Yih is the height or weight for age z-score of child i in household h, β is one of four indicators of slum dwelling for community (i.e. PSU) c in which child i lives and is the coefficient of interest. Xh is a vector of household-level control variables, and Xi is a vector of individual-level control variables. All models cluster the standard errors at the household level to account for the possibility of there being more than one child in a household. The error term, εchi, is assumed to be normally distributed.

The results from the ordinary least squares models precipitate further investigation into the components of the UN definition of slum dwelling that are predictive of poor child health. In this third step, the four components of the UN definition are entered separately into an ordinary least squares regression model as follows:

Where Yih again is the height or weight for age z-score of child i in household h, Xc now stands for a vector of the four characteristics constituting the UN definition of slum dwelling. Xh and Xi are the same vectors of household- and individual-level control variables as in the model with slum designation as a dichotomous indicator variable. This model is run for both health outcomes.

All analyses employed STATA Statistical Software version 13 (StataCorp, 2013) and R version 3.1.0 (R Core Team, 2014).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 3. Table 4 lists the proportion of children in the study sample that are living in slums in each city. Estimates of the proportion slum dwelling vary widely by definition in every city. In the capital city of New Delhi, the UN definition (comprised of community-wide lack of access to improved water, sanitation, and durable housing, and crowding) indicates that 65 percent of children are living in PSUs characterized as slums, whereas the Committee definition (comprised of community-wide unimproved roof material, lack of access to potable water, and poor sanitation facilities) finds only 32 percent of children to be living in slums. The variation is widest in Meerut and Hyderabad, where the UN definition finds over 60 percent of children can be characterized as slum dwelling, while the Committee definition finds the proportion to be close to zero. While the Census definition (which emphasizes legality) systematically produces lower estimates than that of the NFHS definition (which relies on enumerator observations of local surroundings), the UN definition consistently produces higher estimates of the proportion slum-dwelling than both the Census and the NFHS definitions. The Committee definition produces the lowest estimates of all four.

TABLE 4.

Proportion of PSUs in the study sample identified as slums in each city

| City | Census | NFHS | UN | Committee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delhi (n=612) | 44.0 | 38.6 | 65.4 | 32.2 |

| Meerut (n=866) | 51.7 | 34.1 | 61.9 | 1.0 |

| Kolkata (n=389) | 60.4 | 57.3 | 41.9 | 44.0 |

| Indore (n=644) | 52.8 | 8.5 | 34.8 | 11.8 |

| Mumbai (n=368) | 61.4 | 63.3 | 74.5 | 48.6 |

| Nagpur (n=576) | 50.0 | 48.8 | 67.5 | 23.6 |

| Hyderabad (n=719) | 49.4 | 44.6 | 61.2 | 3.1 |

| Chennai (n=435) | 53.3 | 52.0 | 83.7 | 15.4 |

| Total | 51.9 | 40.6 | 60.5 | 14.7 |

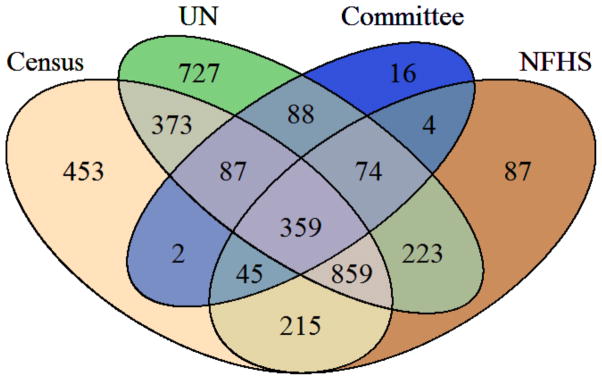

Proportions designated as slum dwelling by each possible combination of two definitions (Table 5) indicates significant variation in overlap between the four definitions. More specifically, while 90 percent of children designated as living in slums by the UN definition are designated as such by the Committee definition, only 54 percent of children designated as living in slums by the UN definition are designated as such by the NFHS definition. Figure 2 presents a Venn Diagram of the overlap between different slum designations. While it does not display these results proportionally, the Venn Diagram provides additional support for the variability in overlap between the definitions. These descriptive results should give pause to researchers, policymakers and public health practitioners who might consider slum dwelling conceptually and/or empirically straightforward.

TABLE 5.

Proportion of children in the study sample identified as living in slums by two definitions

| Census | NFHS | UN | Committee | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census | 100 | |||

| NFHS | 79.2 | 100 | ||

| UN | 60.1 | 54.3 | 100 | |

| Committee | 73.0 | 71.4 | 90.1 | 100 |

FIGURE 2.

Venn Diagram of slum categorization

Table 6 presents the results of bivariate regressions of each of the four slum designations on the two health outcomes. Four regression models are presented, one for each of the four slum definitions. All slum designations are associated with statistically significantly lower height and weight for age of children under 5 years old, although the indicator explains a very small proportion of the variation in the outcome in each case. The negative association between living in a slum and height for ages ranges from 20 percent to one third of a standard deviation in magnitude for height for age for the Census and NFHS definitions, respectively. The negative association ranges from 15 to 30 percent of a standard deviation in magnitude for weight for age for the NFHS and UN definitions, respectively.

TABLE 6.

Bivariate regressions of slum dwelling indicator variable on child health

| Independent variables | Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Census | (2) NFHS | (3) UN | (4) Committee | |

| Height for age | ||||

| Coefficient (sd) | −0.319* (0.051) | −0.331* (0.052) | −0.568* (0.052) | −0.443* (0.072) |

| R2 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.028 | 0.009 |

| Weight for age | ||||

| Coefficient (sd) | −0.224* (0.0039) | −0.182* (0.039) | −0.362* (0.039) | −0.333* (0.054) |

| R2 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 0.010 |

Standard errors clustered at the household level.

statistically significant at p<0.05

Table 7 presents multivariate models of the relationship between the slum dwelling and the two health outcomes, but includes a wide variety of control variables. Four regression models are again presented, one for each of the four slum definitions. When including all covariates, the only slum indicator that is statistically significantly associated (at the 5 percent level) with child height for age is that of the UN. Specifically, children living in slums as characterized by the UN definition have, on average, a height for age z-score that is 0.177 (about 11 percent of a standard deviation) lower than their non-slum dwelling counterparts. The results are similar for weight for age. When including all covariates in the model, the UN definition is the only slum indicator that is statistically significantly associated with child height and weight.

TABLE 7.

Ordinary least squares regression of height for age with each slum definition, coefficient(se)

| Independent variables | Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Census | (2) NFHS | (3) UN | (4) Committee | |

| Slum indicator variable | −0.050 (0.048) | −0.080 (0.052) | −0.177* (0.055) | −0.115 (0.128) |

| Child characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 0.078 (0.0454) | 0.077 (0.046) | −0.177* (0.055) | −0.080 (0.045) |

| Multiple | ||||

| No | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | −0.118 (0.256) | −0.115 (0.255) | −0.136 (0.260) | −0.118 (0.257) |

| Size | ||||

| Small | - | - | - | - |

| Medium | 0.299* (0.068) | 0.303* (0.068) | 0.303* (0.068) | 0.298* (0.068) |

| Large | 0.451* (0.079) | 0.447* (0.079) | 0.452* (0.079) | 0.452* (0.079) |

| Mother characteristics | ||||

| Education | ||||

| None | - | - | - | - |

| Primary | 0.254* (0.093) | 0.250* (0.093) | 0.246* (0.093) | 0.251* (0.068) |

| Secondary | 0.183* (0.074) | 0.183* (0.074) | 0.165* (0.075) | 0.176* (0.074) |

| Higher | 0.478* (0.107) | 0.150* (0.107) | 0.442* (0.109) | 0.478* (0.107) |

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | - | - | - | - |

| Muslim | −0.202* (0.063) | −0.193* (0.063) | −0.162* (0.064) | −0.209* (0.063) |

| Other | 0.151 (0.147) | 0.150 (0.149) | 0.132 (0.147) | 0.148 (0.148) |

| Children born in last 5 | ||||

| 0 | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | −0.106* (0.052) | −0.106* (0.052) | −0.100 (0.051) | −0.106* (0.052) |

| 2 | −0.159* (0.089) | −0.159 (0.089) | −0.141 (0.089) | −0.158 (0.089) |

| Age | 0.005 (0.006) | 0.005 (0.006) | 0.005 (0.006) | 0.004 (0.004) |

| Height | 0.050* (0.004) | 0.050* (0.004) | 0.050* (0.061) | 0.050* (0.004) |

| Work | ||||

| Not working | - | - | - | - |

| Working | −0.236* (0.061) | −0.236* (0.0.061) | −0.241* (0.061) | −0.238* (0.061) |

| Caste | ||||

| Sched. caste/tribe | - | - | - | - |

| Not scheduled | −0.081 (0.063) | −0.076 (0.064) | −0.062 (0.063) | −0.083 (0.063) |

| Migrant | ||||

| Not a migrant | - | - | - | - |

| Migrant – city/town | −0.045 (0.055) | −0.048 (0.055) | −0.045 (0.055) | −0.048 (0.055) |

| Migrant – rural area | −0.026 (0.065) | (0.065) | −0.024 (0.065) | −0.031 (0.063) |

| Partner’s education | ||||

| None | - | - | - | - |

| Primary | −0.026 (0.098) | −0.026 (0.098) | −0.030 (0.098) | −0.032 (0.098) |

| Secondary | 0.088 (0.085) | 0.085 (0.085) | 0.083 (0.085) | 0.080 (0.085) |

| Higher | 0.204 (0.111) | 0.201 (0.111) | 0.186 (0.111) | 0.196 (0.111) |

| Deprivation index | 0.083* (0.015) | 0.082* (0.015) | 0.079* (0.015) | 0.080* (0.016) |

| City fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.1477 | 0.1475 | 0.1494 | 0.1479 |

Standard errors clustered at the household level.

statistically significant at p<0.05

A number of covariates appear to “explain away” the bivariate relationship between the Census, NFHS and Committee definitions of slum dwelling and poor heath, including children’s size at birth, maternal education, being of Muslim as compared to Hindi faith, mother’s height, whether the mother works outside the home, and the household’s wealth. A high level of education on the part of the father is also associated with higher weight for age but not height for age. In order to investigate which of the four components of the UN definition might be driving its relationship with poor health, in spite of the inclusion of these additional covariates, a final ordinary least squares regression model is estimated with all four components – density, housing, water, and sanitation – entered separately.

Rather than dichotomize the four components, they are left as continuous variables representing the proportion of households in the PSU lacking each of the four amenities. The models are run separately for height and weight for age z-scores and indicate that for height for age, it is housing quality that is driving the UN definition’s negative association. More specifically, living in a neighborhood filled with poor as compared to good quality homes (referred to in India as kaccha or semi-pucca, as compared to pucca) is associated with, on average, a 0.483 lower height for age z-score (or about 30 percent of a standard deviation). For weight for age, both housing quality and crowding are statistically significantly associated with lower z-score, with a particularly large effect of density; living in a neighborhood filled with very crowded homes is associated with almost a third of a standard deviation lower weight for age.

DISCUSSION

The results indicate that the way in which slum designation is defined matters for both the descriptive characterization of urban populations as well as both the magnitude and significance of the empirical association between community disadvantage and child health. Indeed, there is significant discrepancy between slum definitions as to which households to designate as being located in a slum. These results strongly suggest that the conceptualization and measurement of slum dwelling requires further theoretical and empirical work given the term’s policy relevance. The mismatch between the UN definition, which is used to compare slum dwelling across countries, and definitions used to monitor individual country’s (like India’s) levels of concentrated urban disadvantage for policy and planning purposes can lead to divergent and even conflicting conclusions and development priorities.

There are a number of potential explanations for the relatively minimal overlap between the four slum designations. First, the Census was conducted in 2001, but the NFHS was undertaken in 2005–2006, making it possible that slum areas changed significantly between Census enumeration and NFHS survey observation and respondent reports (Montana et al., forthcoming), an issue that has not been addressed in studies using these data (Swaminathan and Mukherji, 2012). A second reason for the definition discrepancy may be the significant variation in components that make up the four definitions. While the Census definition relies mainly on notification (i.e. recognition as a legal settlement by a governing body), the other definitions are made up of a variety of characteristics associated with slum dwelling, with one definition based on enumerator observation alone and the two others differing significantly in their stringency in terms of the number of slum-related indicators the households – and by extension the communities in which they are located – must exhibit.

Distinctions such as these are particularly important in the Indian context where legal status confers rights to public service provision; any slum designation that emphasizes legality will underestimate the prevalence of communities with slum characteristics (Agarwal, 2011) and will likely miss the communities experiencing the highest levels of exclusion and disadvantage (Subbaraman et al., 2012). While it is not possible to adjudicate between the proposed explanations for slum designation discrepancy, and it is likely that more than one is operating, this descriptive finding complicates the measurement and policy implications of area deprivation in developing countries.

The regression results, namely that child height and weight for age is negatively associated with only one slum definition net of individual characteristics, points to the need for a more nuanced approach to studying the relationship between area-level deprivation and child health. Given the literature detailing the many probable adverse health effects of living in a slum (Rice and Rice, 2009) and the mechanisms by which disease and poverty are thought to be perpetuated in urban areas (Wratten, 1995), it is surprising that more robust “slum effects” were not uncovered in these analyses. It may be that neighborhood effects impact adult health more significantly than child health, as has been found in Sub-Saharan Africa (Günther and Harttgen, 2012), or that individual and household characteristics are much more proximal and relevant for child height for age (Fink et al., 2014). A relatively “small” effect (as compared to that of individual-level characteristics) of neighborhoods has also been found in developed country cities (Fitzpatrick and LaGory, 2003).

Why might the UN definition in particular be the only slum indicator that is associated with poor child health? One possibility is that it is based on household reporting of current living conditions, which may better capture disadvantage than the Census information, which was based on administrative data collected almost five years before the survey even took place. Slum areas are dynamic in nature and frequent updates are needed to maintain the accuracy of their identification (Montana et al., forthcoming); indeed, information collected at the same time as child health measurement may be particularly informative of health hazards in the immediate vicinity.

It might also be that the way in which slums are characterized by the UN definition is particularly well suited to identifying the characteristics of urban disadvantage that may be most predictive of poor health. The results presented here indicate that a number of individual components comprising the UN definition are associated with poor child health, namely housing quality and crowding. While one can imagine the use of modern floor or roof material may be protective against flooding and the spread of disease as well as being easier to clean, it is also possible that housing type is acting as a proxy for some other, unmeasured, neighborhood advantage. Similarly, high density of living arrangements may promote the spread of infectious disease and may proxy for other characteristics of the area such as large amounts of garbage or open defecation. Since there is no gold standard with which to compare these definitions, it is not possible to discern which of these explanations is most indicative of the underlying process at work. The results highlight, however, the importance of investigating the individual components that comprise slum designation in order to fully understand the underlying mechanisms driving the relationship between area-level poverty and health.

In sum, this is the first study to compare slum definitions as well as to investigate their implications for children’s health in the Indian context in particular. We describe four different ways to characterize what constitutes a slum area, even within just one country, and demonstrate that these definitions frequently do not identify the same households as slum dwelling. The manner in which a slum is defined appears to determine whether or not there is a relationship between slum dwelling and health; only one of the definitions of slum dwelling presented is actually associated with child health when controlling for individual- and household-level characteristics, and this relationship seems to be driven by only 2 of its four components. These findings have implications for the empirical measurement and study of area-level deprivation and intra-urban health inequality, and, by extension, for current policy and media rhetoric focusing on slums (Bhaumik, 2012).

Continued investigation of intra-urban differentials in health (Montgomery, 2009) is therefore recommended, as is more widespread acknowledgement that slums are not homogenous entities (Gaur et al., 2013), but complex and dynamic. One important area of future research is to investigate the use of a slum scale, which may provide more information than a dichotomous slum measure. The use of a slum scale will allow insight into whether there is a cumulative nature to the negative effects of slum dwelling and/or a non-linear relationship between slum adversity and health outcomes, which has been found for common mental disorders in a particularly deprived slum community in Mumbai (Subbaraman et al., under review). Indices have previously been explored in the study of the urban environment more generally; Dahly and Adair find that, using longitudinal data, a scale measure of urbanicity “outperforms the urban-rural dichotomy” (Dahly and Adair, 2008). While a slum index was proposed at an Expert Group Meeting on Urban Indicators at the United Nations in 2002 (UN-HABITAT Urban Secretariat & Shelter Branch, 2002), further action has not been taken.

Further serious research interest on slums will be necessary to inform policy debates on this issue (Marx et al., 2013) and should include the collection of both longitudinal data (Entwisle, 2007) to monitor the evolution of slums, as well as satellite and other spatial data along with ground-based validation (Montana et al., forthcoming). Slum growth is not inevitable (Ooi and Phua, 2007); city governments can and should take responsibility for strategic planning and intervention on behalf of deprived urban populations by linking their area’s economic development trajectories with urban growth, housing, and the infrastructural needs of the individuals and families who come to cities looking for a better life.

TABLE 8.

Ordinary least squares regression of weight for age with each slum definition

| Independent variables | Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Census | (2) NFHS | (3) UN | (4) Committee | |

| Slum indicator variable(sd) | −0.023 (0.037) | −0.073 (0.039) | −0.152* (0.041) | −0.107 (0.058) |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 0.052 (0.033) | 0.052 (0.033) | 0.055 (0.033) | 0.053 (0.033) |

| Multiple | ||||

| No | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | −0.317 (0.198) | −0.374 (0.198) | −0.392 (0.202) | −0.377 (0.198) |

| Size | ||||

| Small | - | - | - | - |

| Medium | 0.269)* (0.051) | 0.271* (0.051) | 0.271* (0.051) | 0.267* (0.051) |

| Large | 0.422* (0.059) | 0.423* (0.059) | 0.423* (0.059) | 0.423* (0.423) |

| Mother characteristics | ||||

| Education | ||||

| None | - | - | - | - |

| Primary | 0.232* (0.069) | 0.232* (0.069) | 0.224* (0.069) | 0.228* (0.069) |

| Secondary | 0.149* (0.055) | 0.147* (0.055) | 0.133* (0.055) | 0.141* (0.055) |

| Higher | 0.402* (0.079) | 0.397* (0.079) | 0.366* (0.080) | 0.397* (0.079) |

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | - | - | - | - |

| Muslim | −0.139* (0.048) | −0.134* (0.048) | −0.104* (0.049) | −0.145* (0.048) |

| Other | 0.015 (0.015) | 0.123 (0.096) | −0.003 (0.095) | 0.010 (0.096) |

| Children born in last 5 | ||||

| 0 | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | −0.021 (0.038) | −0.022 (0.038) | −0.015 (0.038) | −0.020 (0.038) |

| 2 | 0.023 (0.074) | 0.022 (0.074) | 0.040 (0.074) | 0.026 (0.074) |

| Age | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) |

| Height | 0.041* (0.003) | 0.042* (0.003) | 0.041* (0.003) | 0.042* (0.003) |

| Work | ||||

| Not working | - | - | - | - |

| Working | −0.104* (0.047) | −0.104* (0.047) | −0.107* (0.046) | −0.105* (0.047) |

| Caste | ||||

| Sched. caste/tribe | - | - | - | - |

| Not scheduled | −0.019 (0.046) | −0.014 (0.046) | −0.001 (0.046) | −0.019 (0.046) |

| Migrant | ||||

| Not a migrant | - | - | - | - |

| Migrant – city/town | 0.017 (0.042) | 0.017 (0.042) | 0.018 (0.042) | 0.015 (0.042) |

| Migrant – rural area | −0.041 (0.049) | −0.045 (0.049) | −0.039 (0.049) | −0.044 (0.049) |

| Partner’s education | ||||

| None | - | - | - | - |

| Primary | 0.132 (0.074) | 0.133 (0.074) | 0.129 (0.073) | 0.127 (0.074) |

| Secondary | 0.101 (0.064) | 0.101 (0.064) | 0.097 0.064 |

0.094 (0.064) |

| Higher | 0.178* (0.083) | 0.174* (0.083) | 0.163* (0.083) | 0.171* (0.083) |

| Deprivation index | 0.059* (0.011) | 0.057* (0.011) | 0.055* (0.011) | 0.056* (0.011) |

| City fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.1625 | 0.1629 | 0.1651 | 0.1632 |

Standard errors clustered at the household level.

statistically significant at p<0.05

TABLE 9.

Ordinary least squares regression of height for age with UN-HABITAT definition components entered separatelyix

| Independent variables | Coefficient (standard error) Height for age | Coefficient (standard error) Weight for age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community-level slum components | Housing quality | −0.483* (0.174) | −0.271* (0.136) |

| Crowding | −0.273 (0.094) | −0.393* (0.125) | |

| Water | −0.262 (0.173) | −0.058 (0.139) | |

| Sanitation | 0.037 (0.182) | 0.173 (0.130) | |

| R2 | 0.1510 | 0.1631 |

Standard errors clustered at the household level.

statistically significant at p<0.05

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (P32CHD047879 and T32HD007163).

Footnotes

Not applicable (NA) – information on this slum characteristic is not included in this definition

The UN definition technically includes security of tenure and protection against forced eviction. But this is information is not captured in demographic and health surveys and it is therefore standard procedure to omit it from empirical analyses on this topic

More than three people sharing a room

Kachha– houses made out of low-quality materials like mud, thatch or tarpaulin and semi-pucca – houses using a mix of low- and high-quality materials

Unimproved water sources include unimproved dug well, unprotected spring, cart with small tank/drum, bottled water, tanker-truck, surface water (river, dam, lake, pond, stream, canal, irrigation channels)

Coded as not piped into dwelling

Unimproved sanitation facilities include flush or pour-flush to elsewhere, pit latrine without slab or open pit, bucket, hanging toilet or hanging latrine, no facilities, or bush or field

Information on drainage was not included in the National Family and Health Survey; this indicator was coded as the household either sharing a toilet facility or having none at all, i.e. bush or field

Controlling for all the same covariates as in the multivariate models with slum indicators

References

- Agarwal Siddharth. The state of urban health in India; comparing the poorest quartile to the rest of the urban population in selected states and cities. Environment and Urbanization. 2011;23:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal Siddharth, Satyavada Aravinda, Kaushik S, Kumar Rajeev. Urbanization, Urban Poverty and Health of the Urban Poor: Status, challenges and the way forward. Demography India. 2007;36:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal Siddharth, Taneja Shivani. All slums are not equal: child health conditions among the urban poor. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:233–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhan Gautam. Planned Illegalities: Housing and the ‘failure’ of planning in Delhi: 1947–2010. Economic and Political Weekly. 2013;XLVII:58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik Soumyadeep. India outlines plans for National Urban Health Mission. Lancet. 2012;380:550. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquier Philippe, Beguy Donatien, Zulu Eliya M, Muindi Kanyiva, Konseiga Adama, Ye Yazoumé. Do migrant children face greater health hazards in slum settlements? Evidence from Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(Suppl 2):S266–81. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9497-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockerhoff Martin. Child survival in big cities: the disadvantages of migrants. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40:1371–83. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne, Paxson Christina. Stature and status: Height, ability, and labor market outcomes. Journal of Political Economy. 2008;116:499–532. doi: 10.1086/589524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar S, Montgomery Mark R. Paper prepared for the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) London: IIED; 2009. Broadening Poverty Definitions in India: Basic needs and urban housing. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland John, Bernstein Stan, Ezeh Alex, Faundes Anibal, Glasier Anna, Innis Jolene. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. The Lancet. 2006;368:1810–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie Janet, Vogl Tom. Early-Life Health and Adult Circumstance in Developing Countries. Annual Review of Economics. 2013;5:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dahly Darren Lawrence, Adair Linda S. Quantifying the urban environment: a scale measure of urbanicity outperforms the urban-rural dichotomy. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;64:1407–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Snyder, Nelly Salgado V, Friel Sharon, Fotso Jean, Khadr Zeinab, Meresman Sergio, Monge Patricia, Patil-Deshmukh Anita. Social Conditions and Urban Health Inequities: Realities, Challenges and Opportunities to Transform the Urban Landscape through Research and Action. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88:1183–1193. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9609-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton Angus. Height, health and development. National Academy of Science. 2007;104:13232–37. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611500104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton Angus. Height, Health, and Inequality: The distribution of adults heights in India. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings. 2008;98:468–474. doi: 10.1257/aer.98.2.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton Angus, Dréze Jean. Food and Nutrition in India: Facts and Interpretations. Economic and Political Weekly. 2009;XLIV:42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dev Alka, Balk Deborah. Urbanization, Women, and Weight Gain: Evidence from India, 1998–2006. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Dorélien Audrey, Balk Deborah, Todd Megan. What Is Urban? Comparing a Satellite View with the Demographic and Health Surveys. Population and Development Review. 2013;39:413–439. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo Esther. Women Empowerment and Economic Development. Journal of Economic Literature. 2012;50:1051–79. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle Barbara. Putting people into place. Demography. 2007;44:687–703. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmer Deon, Pritchett Lant H. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data--or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38:115–32. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink Gunther, Arku R, Montana Livia. The Health of the Poor: Women living in informal settlements. Ghana Medical Journal. 2012;46:104–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink Günther, Günther Isabel, Hill Kenneth. Slum Residence and Child Health in Developing Countries. Demography. 2014:1–23. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick Kevin M, Lagory Mark. “Placing” Health in an Urban Sociology: Cities as Mosaics of Risk and Protection. City & Community. 2003;2:33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fotso Jean Christophe, Cleland John, Mberu Blessing, Mutua Michael, Elungata Patricia. Birth spacing and child mortality: an analysis of prospective data from the Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system. J Biosoc Sci. 2013;45:779–98. doi: 10.1017/S0021932012000570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galster George C. Neighbourhood Effects: Theory & Evidence. St. Andrews University; Scotland, UK: 2010. The Mechanism(s) of Neighborhood Effects Theory, Evidence, and Policy Implications. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur Kirti, Keshri Kunal, Joe William. Does living in slums or non-slums influence women’s nutritional status? Evidence from Indian mega-cities. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;77:137–46. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goli Srinivas, Arokiasamy P, Chattopadhayay Aparajita. Living and health conditions of selected cities in India: Setting priorities for the National Urban Health Mission. Cities. 2011;28:461–469. [Google Scholar]

- Gragnolati Michele, Shekar Meera, Das Gupta Monica, Bredenkamp Caryn, Lee Yi-Kyoung. Health, Nutrition and Population Discussion Paper. The World Bank; 2005. India’s Undernourished Children: A call for reform and action. [Google Scholar]

- Gruebner Oliver, Khan Md Mobarak H, Lautenbach Sven, Müller Daniel, Kraemer Alexander, Lakes Tobia, Hostert Patrick. A spatial epidemiological analysis of self-rated mental health in the slums of Dhaka. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2011;10:36–50. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-10-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther Isabel, Harttgen Kenneth. Deadly Cities? Spatial Inequalities in Mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review. 2012;38:469–486. [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika Indrajit. Women’s reproductive health in slum populations in India: evidence from NFHS-3. J Urban Health. 2010;87:264–77. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9421-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott John, Maluccio John, Behrman Jere R, Martorell Reynaldo, Melgar Paul, Quisumbing Agnes R, Ramirez-Zea Manuel, Stein Aryeh D, Yount Kathryn M. IFPRI Discussion Paper 01073. International Food Policy Research Institute; 2011. The Consequences of Early Childhood Growth Failure over the Life Course. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (Iips) and Macro International. National Family and Health Survey (NFHS-3) 2005–2006: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Konteh Frederick Hassan. Urban sanitation and health in the developing world: reminiscing the nineteenth century industrial nations. Health & Place. 2009;15:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz Wolfgang, Kc Samir. Global Human Capital: Integrating Education and Population. Science. 2011;333:587–592. doi: 10.1126/science.1206964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx Benjamin, Stoker Thomas, Suri Tavneet. The economics of slums in the developing world. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2013;27:187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation. Report of the Committee on Slum Statistics/Census. New Delhi, India: Government of India, Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development. National Slum Upgrading Strategy and Action. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Urban Housing and Poverty Alleviation. Rajiv Awas Yojana: Guidelines for Slum-Free City Planning. New Delhi: Government of India; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Montana Livia, Lance Peter M, Mankoff Chris, Speizer Ilene S, Guilkey David. Spatial Demography. Using satellite data to delineate slum and non-slum sample domains for an urban population survey in Uttar Pradesh, India. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery Mark R. The Urban Transformation of the Developing World. Science. 2008;319:761–764. doi: 10.1126/science.1153012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery Mark R. Population Bulletin. Washington, D.C: Population Reference Bureau; 2009. Urban Poverty and Health in Developing Countries. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery Mark R, Hewett Paul C. Urban poverty and health in developing countries: household and neighborhood effects. Demography. 2005;42:397–425. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- More Neena Shah, Das Sushmita, Bapat Ujwala, Rajguru Mahesh, Alcock Glyn, Joshi Wasundhara, Pantvaidya Shanti, Osrin David. Community resource centres to improve the health of women and children in Mumbai slums: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:2–10. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan Laura, Balasubramanian Priya, Muralidharan Arundati. Urban Poverty and Health Inequality in India. Population Association of America Annual Meeting; Boston, MA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’hare Greg, Abbott Dina, Barke Michael. A review of slum housing policies in Mumbai. Cities. 1998;15:269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Ooi Giok Ling, Phua Kai Hong. Urbanization and slum formation. J Urban Health. 2007;84:i27–34. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9167-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan Kanchu Charan. RESEARCH, C. F. P, editor. Urban Working Paper. New Delhi, India: Centre for Policy Research; 2012. Unacknowledged Urbanization: The new Census towns of India. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingaswami Vulimiri, Jonsson Urban, Rohde Jon. UNICEF, editor. The Progress of Nations. Geneva: 1996. Commentary: the Asian enigma. [Google Scholar]

- Rice James, Rice Julie Steinkopf. The concentration of disadvantage and the rise of an urban penalty: urban slum prevalence and the social production of health inequalities in the developing countries. International Journal of Health Services. 2009;39:749–70. doi: 10.2190/HS.39.4.i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooban T, Joshua Elizabeth, Rao Umadevi K, Ranganathan K. Prevalence and Correlates of Tobacco use Among Urban Adult Men in India: A comparison of slum dwellers vs non-slum dwellers. Indian Journal of Dental Research. 2012;23:31–38. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.99034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankhe Shirish, Vittal Ireena, Dobbs Richard, Mohan Ajit, Gulati Ankur, Ablett Jonathan, Gupta Shishir, Kim Alex, Paul Sudipto, Sanghvi Aditya, Gurpreet Sethy. India’s Urban Awakening: Building inclusive cities, sustaining economic growth. McKinsey Global Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sclar Elliott D, Garau Pietro, Carolini Gabriella. The 21st century health challenge of slums and cities. Lancet. 2005;365:901–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears Dean. The World Bank Sustainable Development Network Water and Sanitation Program. 2013. How much international variation in child height can sanitation explain? Policy Research Working Paper 6351. [Google Scholar]

- Statacorp; LP, S, editor. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson Rob, Matthews Zoe, Mcdonald JW. The impact of rural-urban migration on under-two mortality in India. J Biosoc Sci. 2003;35:15–31. doi: 10.1017/s0021932003000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss John, Thomas Duncan. Health, nutrition and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature. 1998;36:766–817. [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman Ramnath, Nolan Laura, Shitole Tejal, Sawant Kiran, Shitole Shrutika, Sood Kunal, Nanarkar Mahesh, Ghannam Jess, Betancourt Teresa S, Bloom David E, Patil-Deshmukh Anita. The psychological toll of slum living in Mumbai, India: a mixed methods study. 2014. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman Ramnath, Nolan Laura, Shitole Tejal, Sawant Kiran, Shitole Shrutika, Sood Kunal, Nanarkar Mahesh, Ghannam Jessica, Betancourt Teresa S, Bloom David E, Patil-Deshmukh Anita. The psychological toll of slum living in Mumbai, India: a mixed methods study. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman Ramnath, O’brien Jennifer, Shitole Tejal, Shitole Shrutika, Sawant Kiran, Bloom David E, Patil-Deshmukh Anita. Off the map: the health and social implications of being a non-notified slum in India. Environment & Urbanization. 2012;24:643–663. doi: 10.1177/0956247812456356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman Ramnath, Shitole Shrutika, Shitole Tejal, Sawant Kiran, O’brien Jennifer, Bloom David E, Patil-Deshmukh Anita. The social ecology of water in a Mumbai slum: failures in water quality, quantity, and reliability. BMC Public Health. 2013:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan Hema, Mukherji Arnab. Slums and malnourishment: evidence from women in India. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:1329–35. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taffa Negussie, Chepngeno G, Amuyunzu-Nyamongo M. Child morbidity and healthcare utilization in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya. J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51:279–84. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Un-Habitat. The Challenge of slums: Global Report on Human Settlements. London and Sterling, VA: 2003a. [Google Scholar]

- Un-Habitat. Slums of the World: THe face of urban poverty in the new millenium? 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Un-Habitat. State of the World’s Cities 2006/2007 [Online] Nairobi, Kenya: 2006/7. [Google Scholar]

- Un-Habitat Urban Secretariat & Shelter Branch. Expert Group Meeting on Urban Indicators: Secure Tenure, Slums and Global Sample of Cities. Nairobi, Kenya: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Unger Alon, Riley Lee W. Slum health: from understanding to action. PLoS Medicine. 2007;4:1561–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unicef. [Accessed December 27 2013];Nutrition Definitions [Online] 2013 Available: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/stats_popup2.html.

- United Nations. The Millenium Development Goals Report. New York, NY: United Nations; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Slum population as percentage of urban [Online] 2014 Available: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/SeriesDetail.aspx?srid=710.

- Wratten Ellen. Conceptualizing urban poverty. Environment and Urbanization. 1995;7:11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yach Derek, Mathews Catherine, Buch Eric. Urbanisation and health: methodological difficulties in undertaking epidemiological research in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31:507–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90047-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]