Abstract

A 57-year-old woman was referred to our regional sarcoma unit following a 2-year history of a progressively enlarging mass on her right forearm. At 14×7×12 cm, this mass turned out to be one of the largest upper limb cutaneous malignant melanomas ever described, and, to the best of our knowledge, the first documented in the UK. Remarkably, despite having a T4 malignant tumour with a Breslow thickness of 70 mm, this patient is still alive over 4 years later with no locoregional or distant metastatic spread. We present our experience in the management of this giant malignant melanoma of the upper limb and consider important differentials.

Background

Primary malignant melanomas represent 4% of all new cancer cases in the UK, 19% of them arising from the arms (3rd most common site).1 The term ‘giant melanoma’, although not formally defined, has been previously described as a large diameter melanoma, often over 10 cm.2 The term ‘thick melanoma’ refers to a large malignant melanoma with a Breslow thickness of over 4 mm.2

Giant melanomas are rare. The largest case ever recorded worldwide was 22×25×7 cm, found on the lower back of a patient in the USA.3

To the best of our knowledge, this case represents the first giant malignant melanoma described in the UK. It is also one of the largest upper limb melanomas reported worldwide.

This T4 malignant melanoma demonstrates a remarkable outcome from surgical excision alone with no locoregional or distant metastatic spread over 4 years from presentation.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old woman was referred to our regional soft tissue sarcoma service with a large upper limb mass (figure 1). She had no medical history, however, she did have a family history of breast cancer; she worked as a cleaner. She presented late to her general practitioner, at 2 years, reporting of pain at the site of the lesion. The late presentation was due to extreme anxiety and avoidance of medical settings. On clinical examination, there was a large, pigmented, vegetating mass located on the extensor aspect of her right forearm. She had no sensory, motor or vascular deficits, and had a full range of elbow and wrist movements. Clinically, she had no palpable lymphadenopathy. The leading differential at presentation was that of soft tissue sarcoma.

Figure 1.

Large right forearm mass at time of presentation.

Investigations

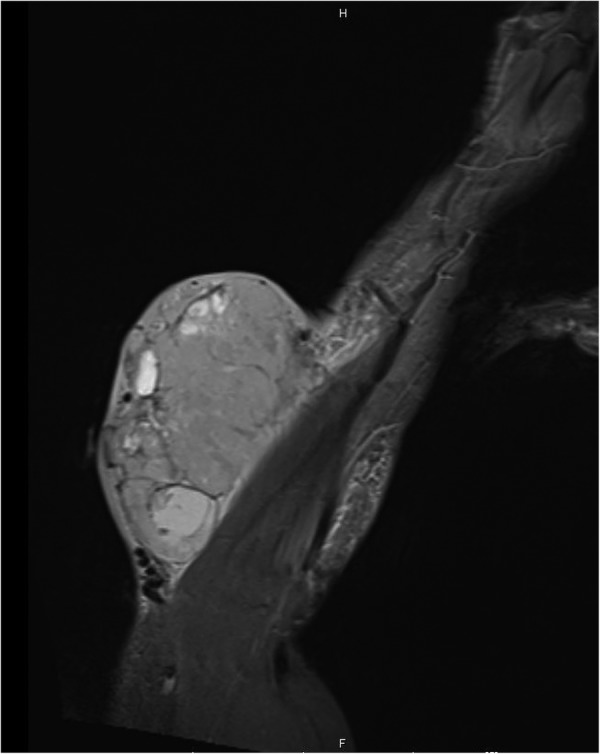

Initial work up of the mass was as per protocol for a potential upper limb soft tissue sarcoma. An initial MRI scan (figure 2) illustrated a 14×7×12 cm soft tissue mass on the ulnar aspect of the proximal forearm.

Figure 2.

MRI showing large soft tissue mass at time of presentation.

An initial staging CT scan and a subsequent positron emission tomography scan showed several enlarged lymph nodes in the right axilla, likely reactive, but no other evidence of distant metastases. These were biopsied under CT guidance and found to be benign.

Differential diagnosis

There are a wide number of differentials to consider when approaching a large superficial soft tissue mass of the upper limb. It is important to consider and rule out soft tissue sarcoma early, and to refer to the regional sarcoma unit and multidisciplinary team (MDT) if clinical suspicion exists. Large lipomatous lesions are most commonly encountered.

Below is a summary, but not an exhaustive list, of other differentials to consider when investigating a large mass on the upper limb, adapted from a classification by Beaman et al.4

Mesenchymal

Lipoma (very common in clinical practice)

Dermatofibrosarcoma protruberans and liposarcomas

Haemangiomas

Nerve sheath tumours, for example, schwannoma and neurofibroma.

Skin

Epidermal cyst

Metastatic

Malignant melanoma, carcinoma and myeloma

Inflammatory

Abscess

Other

Myxoma, cutaneous lymphoma and granuloma annulare

Treatment

Preoperative core biopsies showed features consistent with malignant melanoma. A wide local excision, which included fascia and a cuff of extensor muscle bellies, was performed with curative intent. The defect was covered with a split skin graft from the thigh. At postoperative graft check, there was a 90% take. Such was the level of the patient's anxiety and phobia of medical settings that she was not enrolled in the AVAST-M trial using the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab. This trial was for those deemed at high risk of recurrence from malignant melanoma.

Outcome and follow-up

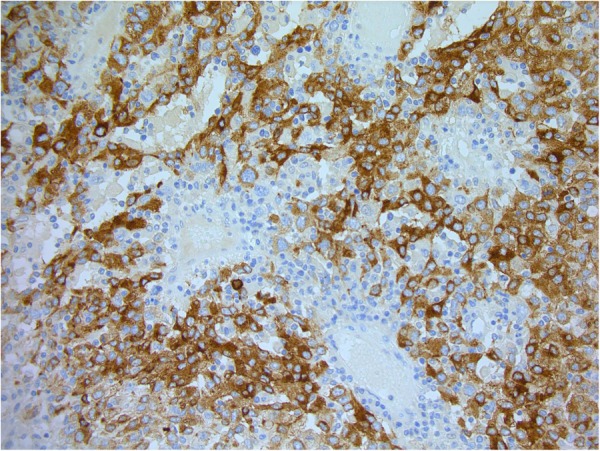

Final histology showed a T4b, N0, M0 nodular malignant melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 70 mm and a Clark's level of V. Further histological testing showed the tumour to be strongly positive for S100 and Melan-A (figure3), confirming the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. The nearest peripheral margin was 30 mm and the nearest deep margin was 0.5 mm, indicating complete surgical excision. This patient was followed up according to current UK Malignant Melanoma guidelines. Figure 4 shows her right forearm after excision and split thickness skin graft (SSG) 4 years after initial resection.

Figure 3.

Histopathology image showing stain for Melan-A (×200).

Figure 4.

Right forearm 4 years after initial excision and SSG.

Discussion

In a systematic review of the literature, di Meo et al5 found only 16 cases of giant malignant melanoma described in the literature, with only three arising from the arms. To the best of our knowledge, this case at 14×7×12 cm is the third largest upper limb melanoma ever recorded and the only case to present in the UK (table 1). This is one of the rare cases, and the only presentation on the upper limb, to have no locoregional or metastatic spread 4 years after initial wide local excision (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of giant upper limb melanomas described in the current literature

| Case | Age | Gender | Size (cm) | Breslow thickness (mm) | LN status | M | Centre |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Del Boz e al6 | 29 | F | 20×20 | 70 | – | Y | Spain |

| Tseng e al (B)7 | 63 | M | 19×19 | 75 | Y | Y | USA |

| Our case | 57 | F | 14×7 | 70 | N | N | UK |

| Tseng e al (A)7 | 88 | M | 8×8 | 31 | N | Y | USA |

LN, lymph node status; M, metastases.

There is no consensus on how best to manage giant malignant melanomas, such is the heterogeneity of the limited cases described in the literature.

Surgical resection with adequate margins remains the only curative approach for malignant melanoma irrespective of size.8 A randomised controlled trial, published in the New England Journal Of Medicine in 2004, indicated that, for malignant melanoma over 2 mm thick, a 3 cm surgical resection margin is recommended.9 These significant resections may require joint input from skin cancer specialists and regional sarcoma teams used to dealing with significant resections.

This case appears to be unique in the literature in terms of its lack of lymph node involvement at presentation and the successful management with no locoregional or metastatic spread in over 4 years.

However, it is important to highlight, as per Marsden et al,8 that the risk of locoregional or distant metastatic disease for T4 malignant melanoma over 4 mm stands at 50%. Other authors, including Tseng et al,7 highlight that distant spread can happen quickly after surgical resection, therefore careful follow-up is paramount.

The 2010 UK malignant melanoma guidelines suggest 3-monthly follow-up for 3 years, 6-monthly for 5 years and annual follow-up for 10 years. They also highlight the fact that there is still a ‘significant risk’ of recurrence after 5 years. Grisham et al10 highlight that lymph node involvement at time of presentation has a significant impact on surgical management in patients with T4 malignant melanoma. The presence or absence of lymph nodes at presentation is seen to directly influence survival.11 Our patient was fortunate enough to be clinically node negative at time of presentation.

The MDT plays a key role in the planning of difficult cases of giant malignant melanoma. However, it is also important to pay particular note to patient factors that may affect outcomes. Our case highlights that, often, patients who present late with such extreme tumours can have underlying phobias or anxieties. Both Tseng et al7 and del Boz et al6 have noted a similar trend including mental health conditions and self-neglect. As a patient group, they may not be suitable for adjuvant therapy due to phobia or compliance issues. In this case, phobia of hospital settings meant our patient was unsuitable for biological therapy, making surgical resection and careful follow-up of paramount importance.

Finally, although it is important to consider primary malignant melanoma as a rare differential of a large superficial upper limb mass, there are a number of more common conditions to consider. As previously mentioned, lipomas are the most commonly encountered benign soft tissue lesions encountered in the upper limb, with sarcoma the key differential to exclude or refer to a regional unit early.

Learning points.

Giant cutaneous malignant melanoma represents a very rare differential for a soft tissue mass in the upper limb.

Surgical resection according to current UK guidelines is, to date, the only curative intervention in the treatment of malignant melanoma.

Patients with ‘giant’ T4 malignant melanomas should be followed up as per national UK guidelines, with monitoring for locoregional recurrence and distant metastasis key even after 5 years.

Patients who present late with large tumours may have underlying phobias, anxieties or mental health conditions. It is important to respect their wishes and limitations, and to tailor treatment accordingly.

Acknowledgments

Dr Keith Miller—Consultant Histopathologist, North Bristol NHS Trust.

Footnotes

Contributors: PW was the consultant surgeon whose care the patient was under, provided the case and asked permission and received consent, and reviewed and gave significant contribution to draft review. CSH was responsible for writing up the case and references, and provided the photos and arranged histology.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK. Skin Cancer Incidence Statistics. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/skin/incidence/uk-skin-cancer-incidence-statistics

- 2.Ching A, Gould L. Giant scalp melanoma: a case report and review of the literature. Eplasty 2012;12:e51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harting M, Tarrant W, Kovitz C et al. Massive nodular melanoma: a case report. Dermatol Online J 2007;13:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaman FD, Kransdorf MJ, Andrews TR et al. Superficial soft-tissue masses: analysis, diagnosis and differentials considerations. Radiographics 2007;27:509–23. 10.1148/rg.272065082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.di Meo N, Stinco G, Gatti A et al. Giant melanoma of the abdomen: case report and revision of the published cases. Dermatol Online J 2014;20:pii:13030/qt4pp2825w. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.del Boz J, García JM, Martinez S et al. Giant melanoma and depression. Am J Clin Dermatol 2009;10:419–20. 10.2165/11311050-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseng W, Doyle J, Maguiness S et al. Giant cutaneous melanomas: evidence for primary tumour induced dormancy in metastatic sites. BMJ Case Rep 2009;2009:bcr07.2009.2073 10.1136/bcr.07.2009.2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsden JR, Newton-Bishop JA, Burrows L et al. Revised U.K guidelines for the management of cutaneous melanoma 2010. Br J Dermatol 2010;163:238–56. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09883.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas JM, Newton-Bishop J, A'Hern R et al. Excision margins in high-risk malignant melanoma. N Engl J Med 2004;350:757–66. 10.1056/NEJMoa030681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grisham AD. Giant melanoma: novel problem, same approach. South Med J 2010;103:1161–2. 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181f3d756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zettersten E, Sagebiel RW, Miller JR III et al. Prognostic factors in patients with thick cutaneous melanoma (>4 mm). Cancer 2002;94:1049–56. 10.1002/cncr.10326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]