Correlation between cell death signaling, nucleotide binding, and ligand binding activities of plant immune receptor variants suggests activation is based on altering the equilibrium between ON/OFF states.

Abstract

NOD-like receptors (NLRs) are central components of the plant immune system. L6 is a Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing NLR from flax (Linum usitatissimum) conferring immunity to the flax rust fungus. Comparison of L6 to the weaker allele L7 identified two polymorphic regions in the TIR and the nucleotide binding (NB) domains that regulate both effector ligand-dependent and -independent cell death signaling as well as nucleotide binding to the receptor. This suggests that a negative functional interaction between the TIR and NB domains holds L7 in an inactive/ADP-bound state more tightly than L6, hence decreasing its capacity to adopt the active/ATP-bound state and explaining its weaker activity in planta. L6 and L7 variants with a more stable ADP-bound state failed to bind to AvrL567 in yeast two-hybrid assays, while binding was detected to the signaling active variants. This contrasts with current models predicting that effectors bind to inactive receptors to trigger activation. Based on the correlation between nucleotide binding, effector interaction, and immune signaling properties of L6/L7 variants, we propose that NLRs exist in an equilibrium between ON and OFF states and that effector binding to the ON state stabilizes this conformation, thereby shifting the equilibrium toward the active form of the receptor to trigger defense signaling.

INTRODUCTION

Nucleotide binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) are now recognized as essential components of cell death and pathogen immunity pathways for metazoan and plant life. A large number of NLRs contain a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain. Immune receptors of this class were first identified in plants as the products of plant resistance (R) genes 20 years ago (Bent et al., 1994; Mindrinos et al., 1994; Whitham et al., 1994; Grant et al., 1995; Lawrence et al., 1995) and later recognized in animals (Inohara et al., 1999; Growney and Dietrich, 2000; Ogura et al., 2001). NLRs are intracellular receptors that recognize danger signals, such as release of mitochondrial cytochrome c and conserved microbial motifs in the case of animal NLRs or secreted pathogen effector proteins in the case of plant NLRs (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Inohara and Nuñez, 2003). In plants, conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are recognized by cell surface pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which induce PAMP-triggered immunity. Pathogens overcome this first level of immunity by secreting virulence effector proteins directly into the host cell, some of which suppress PAMP-triggered immunity. Plant NLRs specifically recognize such pathogen effectors, then called avirulence (Avr) proteins, and activate a second level of resistance, the effector-triggered-immunity. This is often characterized by the induction of a rapid local cell death at the pathogen infection site, termed the hypersensitive response (Jones and Dangl, 2006; Dodds and Rathjen, 2010). Plant NLRs, also referred to as nucleotide binding (NB)-LRRs, consist of a modular structure with a C-terminal LRR domain and a central NB domain. The NB domain is similar to those found in other metazoan NLRs, such as the apoptotic factors Apaf-1 and CED-4, and is thus also referred to as the NB-ARC region (for nucleotide binding, Apaf-1, Resistance proteins, CED-4) (van der Biezen and Jones, 1998). This domain is considered to act as a molecular switch to regulate the activation state (ON versus OFF) of such proteins, depending on the nature of the bound nucleotide. Several studies of plant and animal NLRs have provided evidence indicating that the OFF state is bound to ADP and the ON state is bound to ATP (Tameling et al., 2002, 2006; Bao et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Marquenet and Richet, 2007; Qi et al., 2010; Maekawa et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2011). Plant NLRs also contain a variable N-terminal domain that is mostly represented by a Toll-interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) or a coiled-coil (CC) domain (Bernoux et al., 2011a; Takken and Goverse, 2012). The N-terminal domain of plant NLRs (TIR or CC) can act as a signaling domain (Frost et al., 2004; Michael Weaver et al., 2006; Swiderski et al., 2009; Krasileva et al., 2010; Bernoux et al., 2011b; Collier et al., 2011; Maekawa et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2014) and structure-function analyses demonstrated that self-association of these domains in the flax (Linum usitatissimum) L6 (TIR) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) MLA (CC) proteins is required to activate downstream signaling events (Bernoux et al., 2011b; Maekawa et al., 2011). These observations support a model in which, in the absence of pathogen, NLRs are held in an inactive/ADP-bound state, through intramolecular interactions. Upon effector recognition, nucleotide exchange (ADP to ATP) combined with NLR conformational changes allow the N-terminal domain to initiate signaling (Bernoux et al., 2011a; Takken and Goverse, 2012). However, the mechanisms by which effector perception is linked to NLR activation and what exactly regulates the OFF/ON switch of NLRs are poorly understood.

Because activation of plant NLRs induces cell death pathways, these proteins have to be tightly regulated in the absence of pathogens to avoid uncontrolled defense responses and cell death activation. A few studies have implicated intradomain interactions in NLR autoinhibitory and activation mechanisms. This has been inferred from domain swaps between related proteins, which often lead to either inactive or constitutively active receptors (Luck et al., 2000; Rairdan and Moffett, 2006; Lukasik-Shreepaathy et al., 2012; Qi et al., 2012; Ravensdale et al., 2012; Slootweg et al., 2013; Steinbrenner et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). This has been interpreted as indicating that interacting regions within the proteins have coevolved, and swapping these regions between closely related but polymorphic proteins leads to either the loss of necessary regulatory interactions or the formation of inappropriate interactions resulting in autoactivity or suppression of activity. In some cases, physical interactions have been detected between protein domains expressed in trans (Rairdan and Moffett, 2006; Lukasik-Shreepaathy et al., 2012; Slootweg et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). However, the mechanisms of autoinhibition of NLR proteins remain largely unknown.

The L locus in flax encodes TIR-containing NLR proteins that confer resistance to different strains of the flax rust fungus Melampsora lini. This locus is highly polymorphic, with 12 alleles distinguished by their recognition specificities for effector proteins of the flax rust fungus. The L5, L6, and L7 proteins recognize variants of the corresponding AvrL567 effector and trigger resistance to rust strains expressing these effectors (Lawrence et al., 1981; Dodds et al., 2004), and in the case of L5 and L6, recognition occurs by direct interaction with the corresponding Avr proteins (Dodds et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Ravensdale et al., 2012). Although the L6 and L7 proteins are almost identical, with only 10 polymorphic residues confined to the TIR domain, L7-containing flax gives a weaker resistance phenotype to rust strains that are fully avirulent to L6 (Islam and Mayo, 1990; Ellis et al., 1999). L7 plants also express a weaker cell death response than L6 upon transient expression of seven AvrL567 variants recognized by L6 in planta (Dodds et al., 2006). Similarly, when crossed to stable transgenic lines expressing AvrL567-A, progeny of L7 plants are viable but show mild to strong stunting phenotypes, whereas progeny of L6 plants show an extreme embryo-lethal phenotype in which the seed are collapsed and completely nonviable (Dodds et al., 2004). The polymorphisms in the TIR domain of L7 do not affect the signaling activity of this domain, nor its ability to dimerize. However, in yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays, full-length L7 protein shows a substantially weaker interaction with the AvrL567-A variant compared with L6, even though the TIR domain is not required for this interaction (Bernoux et al., 2011b). This suggests that polymorphisms in the L7 TIR domain likely modify intramolecular interactions, preventing L7 from recognizing AvrL567 proteins and/or from activating a full resistance response. Thus, we used L6 and L7 as a comparison tool to study the mechanisms regulating NLR autoinhibition and activation. Here, we describe a series of reciprocal mutation experiments characterizing the effects of polymorphic sites in the TIR and NB domains on effector-dependent and -independent signaling, nucleotide binding, and effector binding to L6 and L7. The results led us to propose an activation model based on effector-induced alterations of a dynamic equilibrium between the inactive and active states of these NLRs.

RESULTS

Compared with L6, L7 Is Compromised in Both Effector-Induced and Effector-Independent Cell Death Activity

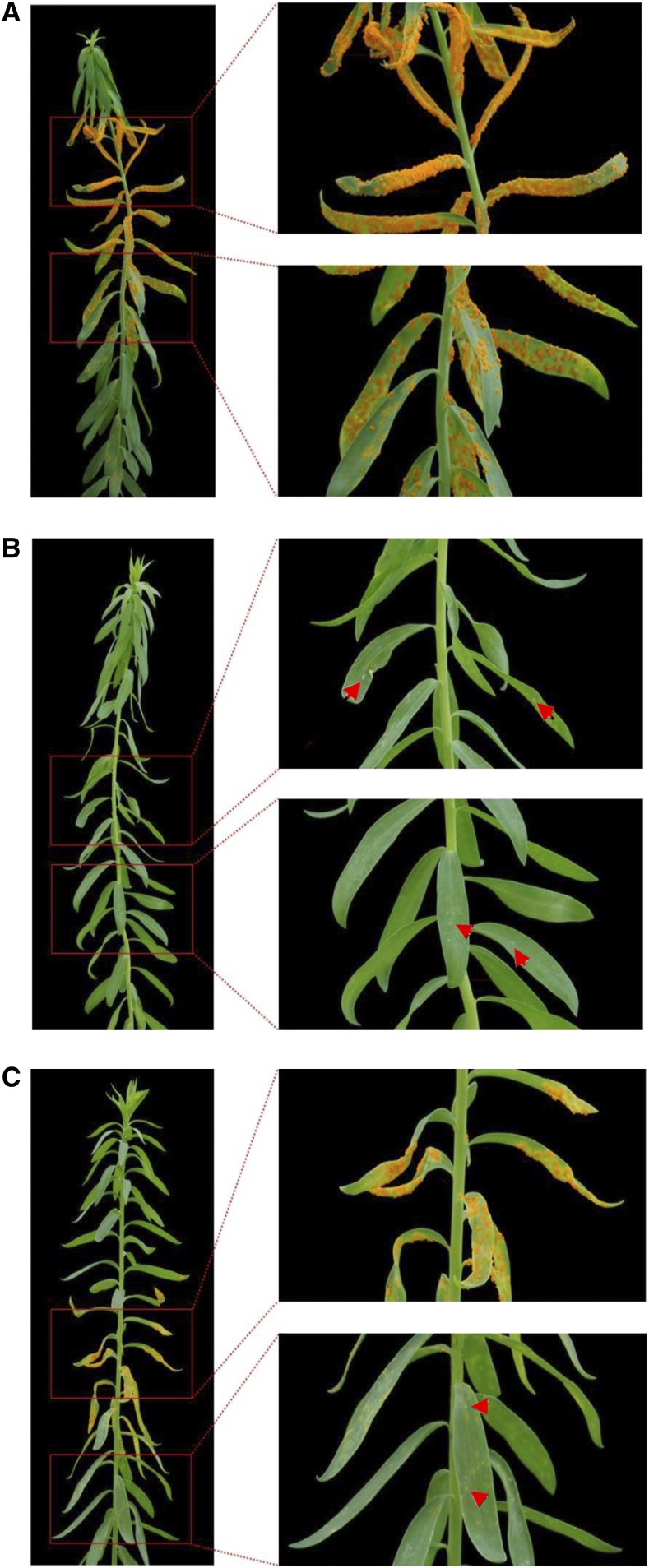

The L6 and L7 proteins differ by only 10 amino acid changes, all in the TIR region (Figure 1), and show similar recognition specificities, although L7 mediates a weaker resistance response (Islam and Mayo, 1990; Ellis et al., 1999). This is illustrated in Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 1, which show flax cultivars containing L6, L7, or L9 genes infected with the flax rust strain CH5F2-138, which is recognized by L6 and L7 but is virulent to L9 (Lawrence et al., 1981). Fourteen days after inoculation, flax cultivar Bison (L9) expressed full susceptibility, with numerous large rust pustules. In contrast, a near isogenic line containing L6 expressed complete resistance to the same rust strain, with small hypersensitive flecks at attempted infection sites (Figures 2A and 2B). The equivalent L7-containing near isogenic line showed an intermediate resistance response, with hypersensitive flecks present on lower leaves and rust pustules on the upper younger leaves, although pustules were considerably smaller than those of the susceptible Bison cultivar (Figure 2C). Similar responses were observed in L6- and L7-containing flax cultivars Birio and Barnes, respectively (Supplemental Figure 1), indicating that the difference in phenotype between L6- and L7-containing plants is not due to the genetic background.

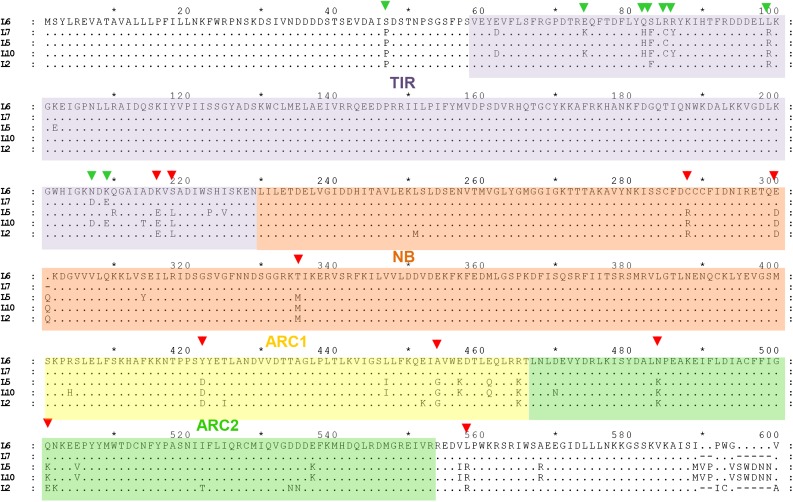

Figure 1.

Sequence Alignment of TIR and NB-ARC Domains of L Proteins from Flax.

Comparison of L6, L7, L10, L5, and L2 amino acid sequences. Residues identical to the L6 sequence are represented as dots and deleted residues as dashes. TIR, NB, ARC1, and ARC2 domains are defined by purple, orange, yellow, and green boxes, respectively, according to L6 TIR domain and APAF-1 NB-ARC domain structures and sequence alignments with other plant R proteins (Riedl et al., 2005; van Ooijen et al., 2008; Bernoux et al., 2011b). L6/L7 polymorphic residues targeted for mutagenesis are indicated by green arrowheads, and other targeted L polymorphic residues are indicated by red arrowheads.

Figure 2.

Phenotype Comparison of Rust-Infected L6- and L7-Carrying Flax Plants.

Rust disease or resistance phenotype on the flax cultivar Bison (A), a Bison backcross line (x12) containing the L6 gene from Birio (B), and a Bison backcross line (x12) containing the L7 gene from Barnes (C) 14 d after inoculation by the flax rust strain CH5F2-138, which carries an allele of AvrL567, the product of which is recognized by L6 and L7. Zoomed regions of upper leaves and lower leaves (outlined in red) on the right side of each plant show differences in leaf reaction after rust infection (disease = orange pustule development or resistance = hypersensitive white flecks, indicated by red arrowheads).

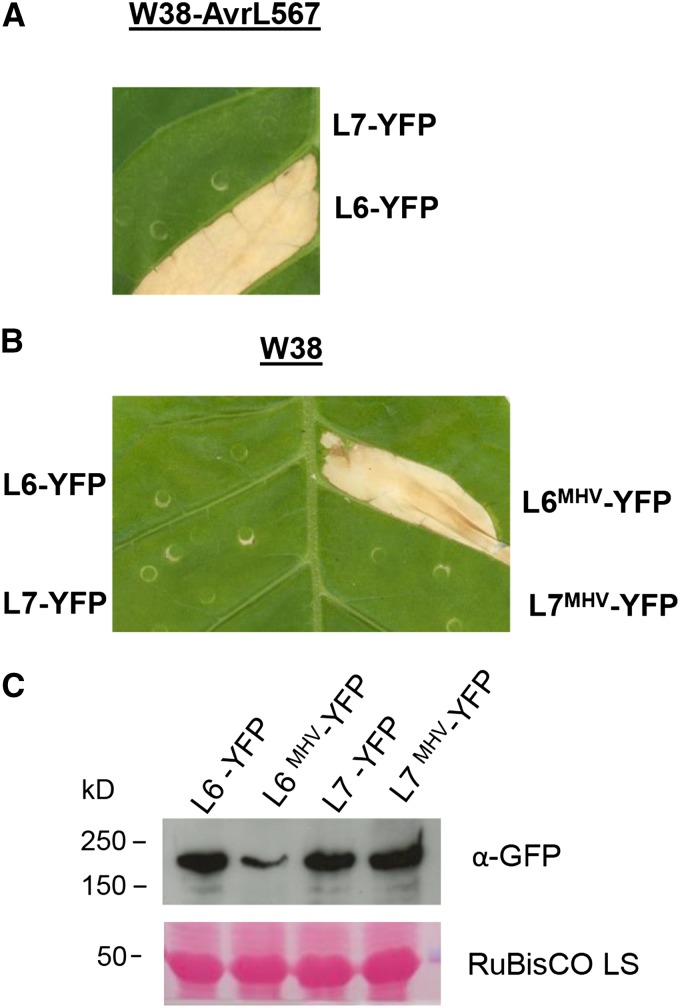

We also examined L6 and L7 protein activity differences by testing their ability to trigger a cell death response in the presence of the corresponding effector AvrL567-A in the tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) heterologous system. In transgenic tobacco expressing AvrL567-A (Dodds et al., 2004), Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transient expression of L6 fused to YFP triggered a strong cell death response 30 to 35 h after agroinfiltration, whereas L7-YFP triggered no or only very weak cell death (Figure 3A). Immunoblot detection demonstrated that both L6-YFP and L7-YFP proteins were expressed at similar levels (Figure 3C). NLR effector-independent activity can be monitored using autoactive mutants that activate defense responses in the absence of their corresponding effectors. For instance, mutations in the conserved MetHisAsp (MHD) motif of many plant NLRs, including L6, induce spontaneous defense and cell death responses (Bendahmane et al., 2002; Howles et al., 2005; van Ooijen et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2011; Stirnweis et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). Replacement of the aspartate by a valine in this motif in L6-YFP (L6MHV-YFP) leads to a protein that constitutively induces cell death when expressed in wild-type tobacco W38 in the absence of the AvrL567 effector (Figure 3B). On the other hand, an identical mutation in L7-YFP (L7MHV-YFP) did not lead to an autoactive phenotype. Immunoblot analysis showed that both the L6MHV and L7MHV fusion constructs are expressed in tobacco, although L6MHV showed lower protein levels than the L7MHV and wild-type L6 and L7 constructs (Figure 3C). This is consistent with previous observations of reduced protein accumulation of the autoactive MMHV protein compared with the wild-type M protein (Williams et al., 2011), possibly due to a higher protein turnover of MHV mutants because of their autoactive phenotype.

Figure 3.

L7 TIR Domain Polymorphisms Prevent Effector-Dependent and -Independent Cell Death Activation.

(A) Representative cell death phenotype of L6 and L7 fused to YFP 4 d after agroinfiltration in transgenic tobacco W38 expressing AvrL567. Effector-dependent cell death caused by L6 was visible 30 to 35 h after infiltration. Total number of repeats is indicated in Figure 4B.

(B) Representative cell death phenotype of L6MHV and L7MHV fused to YFP 4 d after agroinfiltration in wild-type tobacco W38. Effector-independent cell death caused by L6MHV was visible 30 to 35 h after infiltration. Total number of repeats is indicated in Figure 5A.

(C) Immunoblot detection of YFP protein fusions using anti-GFP antibodies. Proteins samples were taken 28 h after agroinfiltration in tobacco W38. Protein loading is indicated by red Ponceau staining of the Rubisco large subunit (LS).

Because expression of only the TIR domain of L7 induces cell death, the polymorphisms in the L7 TIR domain do not affect its signaling activity (Bernoux et al., 2011b). Thus, these data suggest that polymorphisms in L7 TIR may either participate in autoregulatory mechanisms in the absence of pathogen or interfere with effector recognition through intramolecular interactions with other domains of the protein.

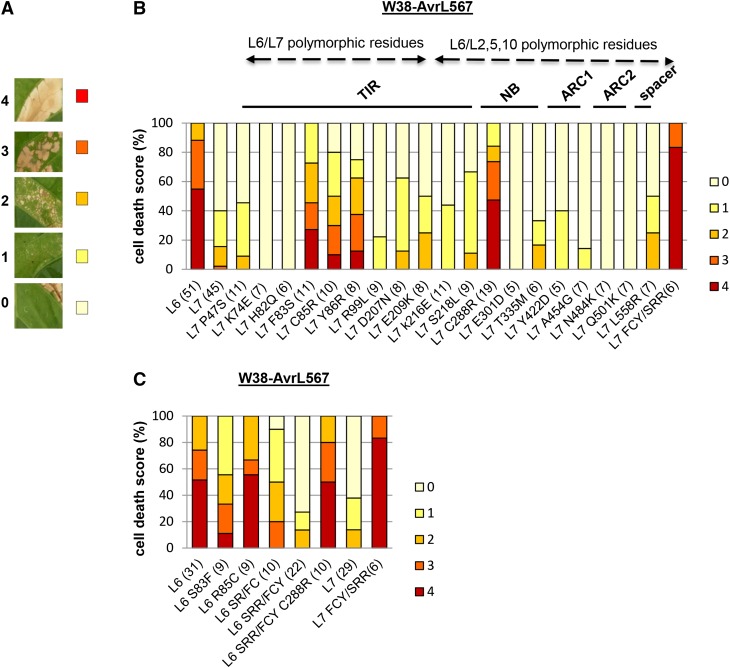

Negative Interactions between Polymorphic Sites in the TIR and NB Domains Prevent Effector-Triggered Activation of L7

To identify which residues in the TIR domain of L7 are responsible for its weaker activity compared with L6, we introduced the corresponding L6-derived amino acids at each of nine (out of 10 in total) polymorphic sites into the TIR domain of the L7 full-length sequence (Figure 1) and tested the resulting mutants for effector-dependent cell death activity (Figures 4A and 4B). When expressed in transgenic AvrL567 tobacco, three L7 mutants, Phe83Ser (F83S), Cys85Arg (C85R), and Tyr86Arg (Y86R), triggered a cell death response that was substantially stronger than that induced by L7, although still slightly weaker than the L6 phenotype. The six other mutants showed a response similar to wild-type L7. The cell death activity observed for L7F83S, L7C85R, and L7Y86R is effector dependent, as no autoactive cell death response was induced when these proteins were expressed in wild-type tobacco without AvrL567 (Supplemental Figure 2). A triple mutant in L7 in which these three residues were all exchanged for the corresponding L6 residues (Phe83Ser, Cys85Arg, and Tyr86Arg [FCY/SRR]) triggered a cell death response that was very similar to that of L6 (Figure 4B; Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Reciprocal Mutations in the TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) Regions of L7 and L6 Have Complementary Effects on Effector-Dependent Signaling Activity.

(A) Cell death scoring scale from 0 (no cell death, pale-yellow color) to 4 (confluent cell death, red color).

(B) Cell death activity of L7 mutants.

(C) Cell death activity of L6 mutants.

(B) and (C) Graphs representing effector-dependent cell death activity of L7 and L6 mutants, fused to YFP, represented as a percentage of infiltrated panels producing each cell death score (color-coded bars as indicated in [A]) 3 d after infiltration. Each mutant was tested in at least three independent infiltration experiments in transgenic tobacco W38 expressing AvrL567 together with L6 and L7 as controls on the same leaf. For each mutant, the total number of scored leaves is indicated in parentheses following each corresponding construct on the abscissa axis. Location of mutations is indicated above the scoring bars with black straight line defining mutations within the TIR, NB, ARC1, and ARC2 domains or ARC2/LRR spacer region and dashed arrows defining mutations in residues polymorphic between L6 and L7 or polymorphic between L6 and L2, L5, and L10.

Interestingly, other L alleles, such as L5, L10, and L2, contain similar polymorphisms to L7 in this region of the TIR domain (Figure 1), yet show strong rust resistance activity similar to L6, and in the case of L5, a strong cell death phenotype was observed when coexpressed with AvrL567-A (Ellis et al., 1999; Dodds et al., 2006; Ravensdale et al., 2012). This suggests that amino acid differences in other regions of L5, L10, and L2 may compensate for the inhibitory TIR polymorphisms in L7 and thus allow stronger activation of these proteins. To test this hypothesis, we introduced further single residue substitutions into L7 at 10 sites (two in TIR, seven in NB-ARC, and one in LRR domains) where L2, L5, and L10 contain residues that differ from L6 and L7 (Figure 1). Mutation of one of these residues in the NB domain (Cys288Arg [C288R]) enhanced L7 cell death activity to L6 levels when expressed in AvrL567-containing tobacco and was not autoactive when expressed in a wild-type tobacco (Figure 4B; Supplemental Figure 2). The other nine mutants were similar in phenotype to L7 and all showed a similar level of protein expression as wild-type L6 and L7 (Figure 4B; Supplemental Figure 4).

To test whether the reciprocal mutations in these two regions would have an effect on L6 effector-dependent cell death activity, we first introduced the L7-derived residues into the L6 TIR region. Single mutations at positions 83 and 85 did not substantially diminish the L6 activity, while a double mutant S83F-R85C had an intermediate phenotype and the triple mutation (SRR/FCY) showed a very weak cell death activity similar to L7 (Figure 4C; Supplemental Figure 3B). No differences in protein expression compared with the wild-type L6 protein were observed for these mutants (Supplemental Figure 4). Furthermore, the activity of the triple mutant reverted to wild-type L6 level when an additional C288R mutation was introduced, which recapitulated the result obtained with the L7C288R mutant (Figure 4C; Supplemental Figure 3), supporting the hypothesis that a negative interaction involving the TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) regions is responsible for reduced activity of L7.

Negative Interactions between Polymorphic Sites in the TIR and NB Domains Prevent Effector-Independent Activation of L7

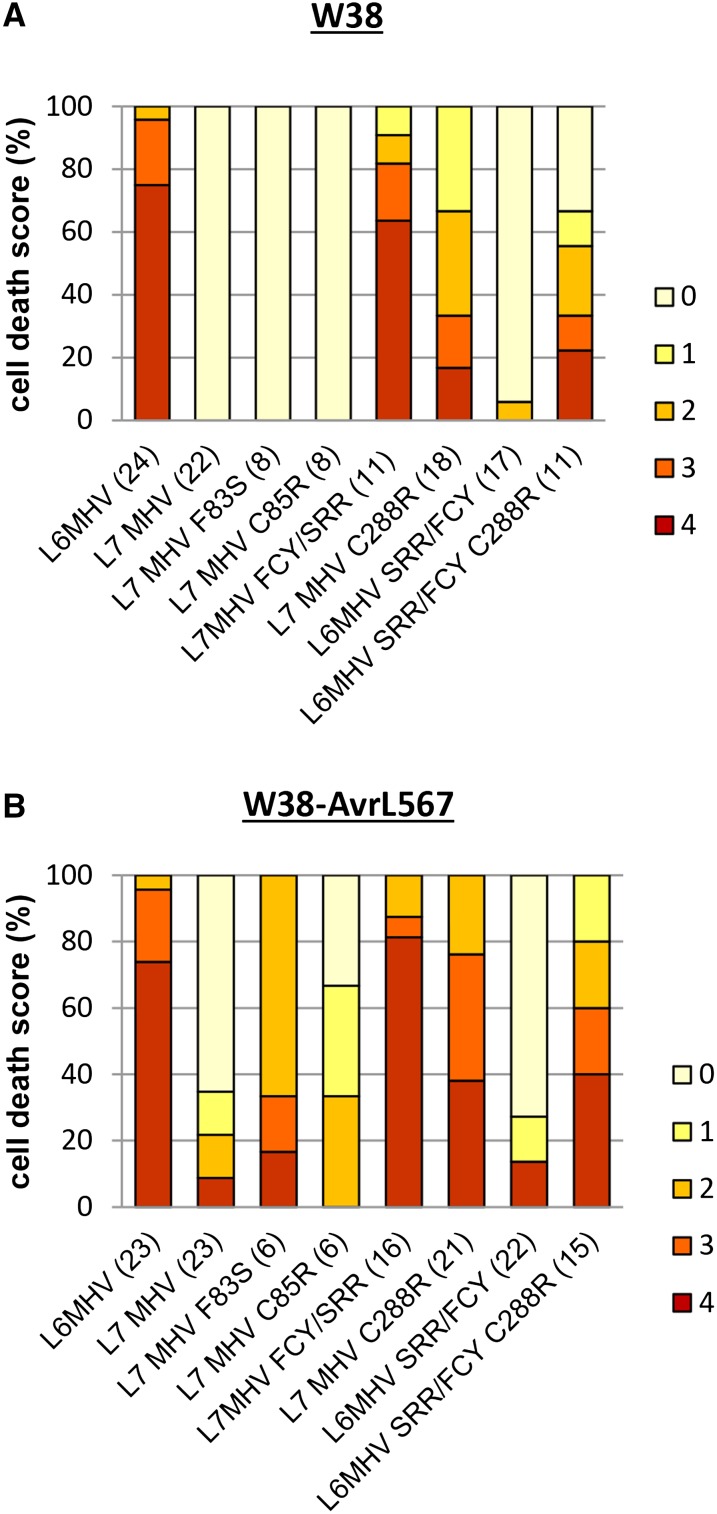

To test whether the interaction between the L7 TIR and NB regions also contributes to inhibiting the effector-independent cell death activity of L7MHV mutant, we made similar amino acid substitutions in the TIR and the NB domains at residues 83, 85, 86, and 288 in the nonautoactive L7MHV mutant background and tested these mutants for gain of autoactivity. While single mutations at positions 83 and 85 had no effect, the triple substitution FCY/SRR was fully autoactive when expressed in wild-type tobacco (Figure 5A; Supplemental Figure 5A). The C288R mutation in the NB domain of L7MHVwas also autoactive, but not to the same level as L6MHV or L7MHV,FCY/SRR. Conversely, introducing the three L7 polymorphisms in the TIR domain of L6MHV (L6MHV,SRR/FCY) resulted in the inhibition of autoactivity. Again, reintroducing an arginine in the NB domain at position 288 in the L6 triple mutant background (L6MHV,SRR/FCY,C288R) partially restored the autoactive phenotype (Figure 5A; Supplemental Figure 5A). We conclude that polymorphisms in the TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) regions inhibit both L7 effector-dependent activity and L7MHV autoactivity.

Figure 5.

Reciprocal Mutations in the TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) Regions of L7 and L6 Have Complementary Effects on Effector-Independent Signaling Activity.

Autoactive cell death activity of L6MHV and L7MHV mutants, fused to YFP, represented as a percentage of infiltrated panels producing cell death score (color-coded bars as in Figure 4) 3 d after infiltration. Each mutant was tested in at least six independent infiltration experiments in wild-type W38 tobacco (A) or in transgenic tobacco W38 expressing AvrL567 (B), together with L6MHV and L7MHV as controls on the same leaf. For each mutant, the total number of scored leaves is indicated in parentheses following each corresponding construct on the abscissa axis.

Interestingly, when the same set of mutants in L6MHV and L7MHV background was tested in transgenic tobacco expressing AvrL567, a substantially stronger cell death response was induced compared with that in wild-type tobacco (Figure 5B; Supplemental Figure 5B). In some cases, L7MHV and L6MHV,SRR/FCY also triggered a weak cell death in the presence of AvrL567, suggesting that although their autoactivity is inhibited, they retain some activity that can be enhanced upon effector recognition. The same observation was made when L6MHV and L7MHV mutants were expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana, with a stronger cell death response observed when these constructs were coexpressed with AvrL567 (Supplemental Figures 6A and 6B). In order to verify that the observed differences in phenotype were not due to a difference in protein expression levels in wild-type and transgenic tobacco, we compared protein accumulation of all mutants in the presence or absence of the effector AvrL567. We previously observed that L6MHV protein is less stable than the wild-type protein when expressed in tobacco (Figure 3C), possibly due to a higher protein turnover as a consequence of a strong and fast cell death activity, thus making it difficult to follow and compare protein expression levels in this plant system. However, although the cell death phenotype observed for L6MHV, L7MHV, and their mutants in tobacco could be recapitulated in N. benthamiana, the cell death response was slower and less extensive in this plant species (Supplemental Figures 6A and 6B). Therefore, we used N. benthamiana to monitor and compare protein accumulation of L6 MHV and L7 MHV mutants in the presence or absence of the effector AvrL567. All protein accumulated at similar levels in this system (Supplemental Figure 6C). Thus, the phenotypic differences observed in these experiments could be ascribed to additional activation caused by AvrL567 and not to differences in protein accumulation.

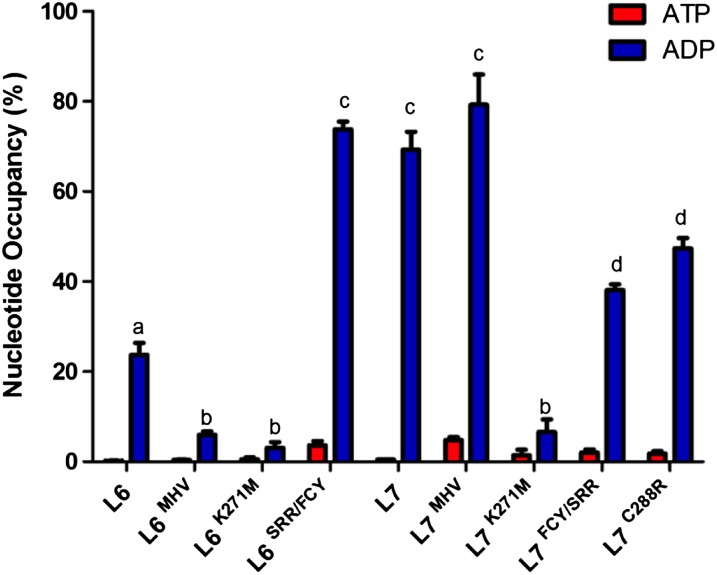

The TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) Polymorphic Regions Influence the Nucleotide Binding Activity of L6 and L7

In a previous study, we showed that the flax NLR receptor M preferentially binds to ADP, whereas the autoactive M MHV mutant binds preferentially to ATP, suggesting that the ADP-bound state corresponds to the OFF/inactive version of the receptor, whereas the ATP-bound state is the ON/active state that signals defense (Williams et al., 2011). Here, our results suggest that a functional interaction between the TIR and NB regions inhibits the ability of L7 to transition to an activated state, compared with the L6 protein. If this is correct, L7 should be held in an autoinhibited ADP-bound/OFF state more tightly than L6. To test whether L6 and L7 differ in their nucleotide binding activities, we quantified the amount of ADP and ATP bound to the purified NLR proteins (Williams et al., 2011). The L6 and L7 proteins were expressed with N-terminal 6Xhistidine tags in the yeast Pichia pastoris and purified by nickel affinity (NiA) chromatography (Supplemental Figures 7 and 8). Immunoblot analysis of the nickel affinity purified L6, probed with an anti-hexa-His antibody, indicated that the majority of the protein corresponds to full-length protein (Supplemental Figure 8). The concentration of ADP and ATP associated with the samples of purified proteins was measured by a luciferase assay (Williams et al., 2011), and ADP and ATP occupancies were calculated as a percentage of protein molecules associated with each nucleotide (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

ATP/ADP Quantification of L6, L7, and Their Mutants.

The percentage of L6, L7, and mutant proteins occupied by ATP and ADP was determined after NiA purification and concentration. L6K271M and L7K271M P-loop mutants were used as negative controls and confirmed that other copurifying proteins did not contribute to measurements of ATP and ADP. Nucleotide occupancy measurements of all proteins were done in triplicate and recorded with error bars representing 1 sd from the mean. One-way ANOVA, Tukey’s HSD post hoc test, and tests for normality and equal variances have been run and revealed the presence of four statistically different groups for ADP values (a to d). ATP occupancy was negligible in all samples and not significantly different from each other.

For the L6 protein, we found an ADP occupancy of 23.7% ± 4.6%, while negligible levels of bound ATP were detected (0.2% ± 0.1% occupancy). In contrast to the flax autoactive MMHV mutant, found to preferentially bind ATP (Williams et al., 2011), the corresponding L6MHV mutant bound negligible amounts of either ATP (0.4% ± 0.2%) or ADP (6.0% ± 1.3%) (Figure 6). The decreased stability of the L6MHV ADP-bound form is consistent with its autoactive phenotype, but the lack of ATP binding suggests that the active state/ATP-bound form of this autoactive protein may be less stable than its MMHV counterpart and therefore is not able be captured in the time frame of this experimental purification system. Of greatest significance to this study, we found that the L7 and L7MHV proteins bound higher levels of ADP (69.2% ± 6.9% and 79.2% ± 6,7%, respectively), suggesting that the OFF state is more stable than in L6, consistent with the observation that L7MHV is not autoactive. A K271M mutation in the P-loop motif of the NB domain, which is known to abolish the functions of many NLR proteins and is expected to prevent nucleotide binding (Tameling et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2011), substantially reduced nucleotide binding of both L6 and L7 proteins. This demonstrates that nucleotides detected after NiA purification can be directly attributed to the purified NLR proteins and not to copurifed P. pastoris proteins (Figure 6).

To test whether the difference in nucleotide binding properties between L6 and L7 is determined by the polymorphisms that regulate L6 and L7 effector-dependent and -independent signaling activity, we measured the nucleotide occupancy of L6 and L7 recombinant proteins with reciprocal exchanges in the TIR and NB regions (Figure 6). A triple mutation in the TIR domain of L6 (SRR/FCY) enhanced its ADP binding to levels similar to L7 (73.8% ± 2.9%), while the reciprocal changes in L7 (FCY/SRR) reduced the ADP occupancy to 38.7% ± 3.3% ADP (Figure 6). Similarly, a mutation in the NB domain at position 288 also reduced L7 ADP occupancy to 45.59% ± 4.70%. Altogether, these results show that the L7 polymorphisms that inhibit receptor function lead to stronger ADP binding, which is consistent with our hypothesis that L7 is held more strongly in an OFF/inactive state than L6 as a result of contacts between these polymorphic residues within the TIR and NB domains.

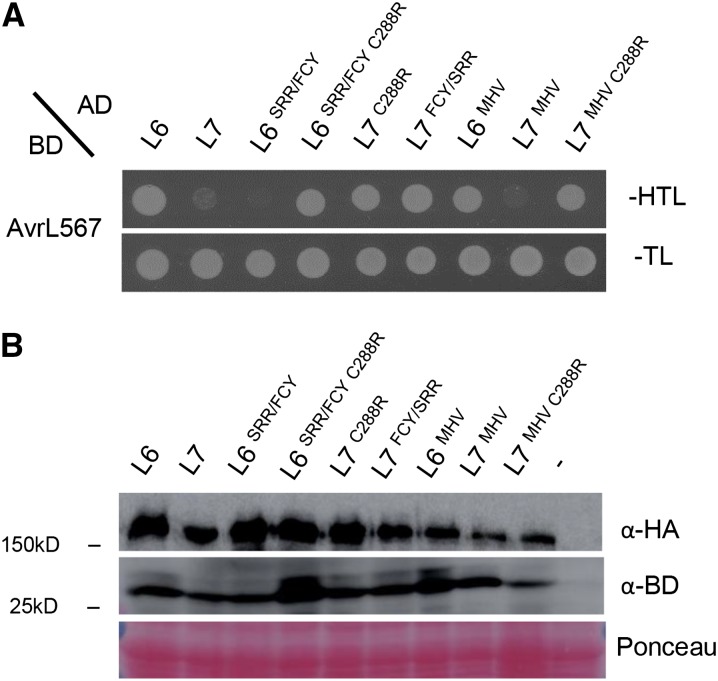

The Flax Rust Effector AvrL567 Binds Preferentially to Active Receptors

As previously described, L6 binds AvrL567 in yeast, whereas L7 shows a very weak interaction with the same effector (Dodds et al., 2006; Bernoux et al., 2011a). Therefore, we tested the interaction of AvrL567 with L6, L7, and selected mutant variants in a Y2H assay to determine if signaling activity is also linked to effector binding. We observed a clear correlation between receptor signaling activity and effector interaction for the L6 and L7 variants (Figure 7A). L7 and L6 mutants that are signaling competent in planta (L7FCY/SRR, L7C288R, and L6SRR/FCY C288R) showed a strong interaction with AvrL567 in yeast, similar to that observed for L6. By contrast, the L6SRR/FCY mutant that has a reduced signaling activity in planta also showed a reduced interaction with AvrL567, similar to L7 (Figure 7A). Similar results were observed with L6 and L7 containing an MHV mutation. The L6MHV mutant, which is autoactive in tobacco, showed an interaction with AvrL567, whereas nonautoactive L7MHV did not. Again, a mutation in the NB domain (position 288) in the L7MHV background, which enables autoactivity partially when expressed in wild-type tobacco and fully when expressed in AvrL567-containing tobacco (Figure 5), also acquired a physical interaction with AvrL567 in yeast (Figure 7A). All protein constructs tested were stably expressed in yeast (Figure 7B). AvrL567 binding was only detected for signaling active receptor variants and not for the inactive variants, which had enhanced stability of the ADP-bound form (Figure 6), suggesting that these receptors have a low affinity for their ligand when in the inactive ADP-bound/OFF state and that effector binding is therefore mediated by the active ATP-bound/ON state.

Figure 7.

R/Avr Physical Interaction in Yeast.

(A) Growth of yeast cells expressing GAL4-BD-AvrL567-A and GAL4-AD fusions of L6 or L7 mutants on nonselective medium lacking tryptophan and leucine (-TL) or selective medium additionally lacking histidine (-HTL).

(B) Immunoblot detection of GAL4-BD-AvrL567 fusions and GAL4-AD fusions of L6 or L7 mutants using anti-BD and anti-HA antibodies, respectively. Protein loading is indicated by red Ponceau staining. The negative control is indicated by a dash and corresponds to untransformed yeast.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide functional and biochemical evidence to demonstrate that two regions in the TIR and the NB domain of the flax immune receptors L6 and its “weak” allele, L7, regulate the activation of these two receptors. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we identified three polymorphic residues (at positions 83, 85, and 86) as responsible for the weaker activity of L7 compared with L6 in both effector-dependent and effector-independent (autoactive) cell death signaling (Figures 4 and 5). Sequence comparison of other strongly active L-alleles identified potential interacting sites in other regions of the protein, and mutagenesis showed that residue C288 in the NB-ARC region is also required for the negative inhibitory effects of the L7 TIR polymorphisms. Reciprocal mutations in the L6 protein confirmed that these two regions in the TIR and NB domains are solely responsible for the weak L7 resistance phenotype, since the L6SRR/FCY mutant lost activity (L7-like activity), which could then also be recovered by introduction of the C288R mutation (Figure 4C; Supplemental Figure 3B). These results suggest that a negative functional interaction between the TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) regions inhibits L7 activation and is responsible for its weak resistance phenotype.

We have also shown that L7 purifies from a yeast expression system with ∼3-fold more bound ADP than L6 (69% of L7 protein bound with ADP, compared with 23% for that of L6) (Figure 6), indicating that ADP molecules are bound more tightly to L7 and that the OFF state of L7 is more stable during protein purification compared with that of L6. We hypothesize that this biochemical property inhibits the release of ADP from L7 and, hence, the subsequent exchange for ATP and structural changes that are needed to adopt a signaling active state, explaining the weaker rust resistance activity of L7 compared with L6. The same TIR domain polymorphisms that regulate the signaling activity of L6 and L7 also influence the nucleotide binding properties of these proteins (Figure 6), with the inactive L6FCY/SRR showing similar enhanced ADP binding to L7, while the active L7SRR/FCY and L7C288R mutants have reduced ADP binding similar to L6. Thus, the strength of the hypersensitive response phenotype induced by L6, L7, and their mutant proteins in planta appears to be inversely related to the stability of the ADP-bound state of the receptor.

Biochemical and structural studies of plant NLRs, as well as non-plant STAND (signal transduction ATPases with numerous domains) proteins, including Apaf-1, MalT, and CED4, suggest that the ATP-bound states are associated with the activated forms of these proteins (Tameling et al., 2002, 2006; Bao et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005; Marquenet and Richet, 2007; Qi et al., 2010; Maekawa et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2011). These observations led to the “switch” model, in which the NB-ARC domain acts as a molecular switch to regulate the activation of these receptors (Takken et al., 2006; Faustin et al., 2007). In these and subsequent descriptions (e.g., Bernoux et al., 2011a, Takken and Goverse, 2012), it has been considered that binding of an effector to the resting NLR in the ADP-bound/OFF state leads to transduction of an intramolecular signal to the remainder of the protein, resulting in a conformational change that allows exchange of ADP for ATP and adoption of the active/ON state to activate defense signaling.

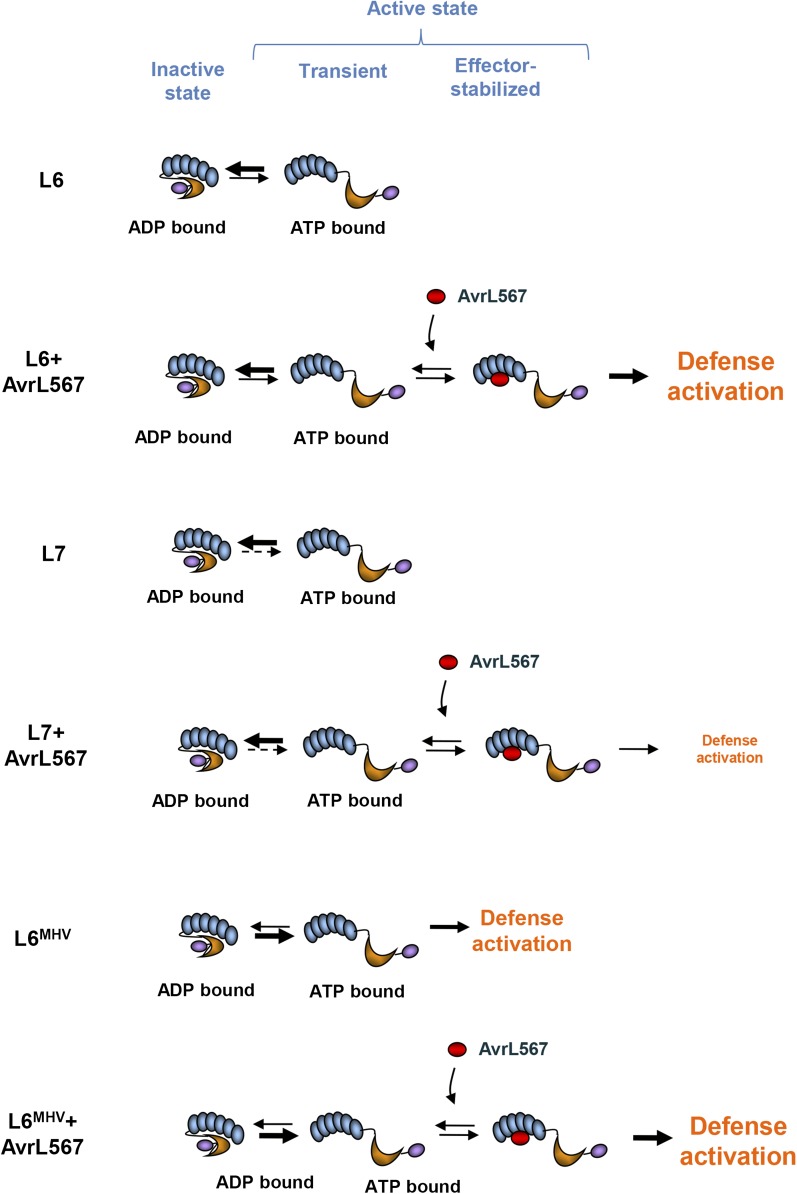

In this study, we were able to examine the binding of the AvrL567 effector to a series of L6/L7 variants that either have normal function or are strongly held in the inactive, ADP-bound state. We found that AvrL567 binding was reduced in the autoinhibited L6/L7 variants but was stronger for those forms (L6 wild type and L7 mutants) that can activate a strong cell death response (Figure 7). L7 and the L7-mimetic L6SRR/FCY mutant, which showed enhanced ADP binding, did not bind AvrL567, while L6, L7FCY/SRR, and L7C288R, with lower ADP affinity, bound AvrL567. Likewise, a P-loop mutant of L6 that fails to bind ADP or ATP (Figure 6) also does not bind AvrL567 (Dodds et al., 2006). This negative correlation between ADP and AvrL567 binding suggests that AvrL567 binds preferentially to the receptor in its ON/ATP-bound state and not to the OFF/ADP-bound state as predicted by the original “switch” model. This of course requires that at least some of the receptor protein must be present in an ON state in the absence of the pathogen in order to bind its corresponding effector. Indeed, both ADP-bound and ATP-bound forms of the flax M receptor protein can be detected in vitro, although the ADP-bound state is predominant (Williams et al., 2011). Furthermore, ATPase activity has been reported for several plant and animal NLRs (Tameling et al., 2002; Ueda et al., 2006; Duncan et al., 2007; Reubold et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2013), suggesting that once bound to ATP, NLRs can be reset to their OFF position through ATP hydrolysis and that they can cycle through these states in the absence of the effector ligand. Therefore, we propose that effector-dependent activation of NLRs is based on an “equilibrium-based switch” model (Figure 8). In this model, NLRs cycle between an OFF/ADP-bound and ON/ATP-bound state in the absence of a pathogen, with this equilibrium strongly favoring the inactive ADP-bound state to avoid inappropriate defense activation, but allowing the uninfected plant cell to constitutively present a small pool of active receptor ready to respond and activate downstream signaling responses very rapidly upon pathogen infection and effector binding. Rather than binding to the OFF state and causing it to switch to the ON state as previously envisaged, effector binding to the ON/ATP-bound state would stabilize this state and prevent recycling to the “off state,” hence shifting the equilibrium toward the ON side of the reaction thereby leading to defense signaling (Figure 8). This model is consistent with other biochemical views that describe allosteric proteins as an ensemble of states with constant dynamic changes with the equilibrium regulating these changes shifted by the presence of an effector to stabilize the active state (Tang et al., 2007; Motlagh et al., 2014). It is also consistent with predictions raised from the structural analysis of the full-length apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1), suggesting that this member of the STAND family is likely to bind its ligand, the cytochrome c, when in its ON/ATP-bound state (Reubold et al., 2011).

Figure 8.

The Equilibrium-Based Switch Activation Model.

Cartoon representation of L6 activation compared with L7 and the autoactive mutant L6MHV. The N-terminal TIR domain is represented by a purple oval, the NB-ARC domain by an orange crescent, and LRRs by a series of blue ovals. In the absence of effector, L6 can cycle between an OFF/ADP-bound and ON/ATP-bound state. To avoid inappropriate defense activation, this equilibrium strongly favors the inactive ADP-bound state but allows a small amount of activated ATP-bound receptor (transient state) to be available for effector binding/recognition. Upon effector recognition, effector binding would thus stabilize the active state and shift the equilibrium toward this side of the reaction, thereby leading to defense signaling. In the case of L7, negative interactions between the TIR and NB domains favor the OFF state of the equilibrium relative to that of L6, decreasing the amount of active receptor available and thus inhibiting the defense activation in the presence of the effector. The L6MHV mutant is constitutively active, indicating that the OFF/ON equilibrium is shifted toward the ON state. However, binding of the effector to the transient active state shifts this equilibrium even further to induce a stronger cell death response. The rate of the forward and reverse reactions of the OFF/ON equilibrium are schematically represented by different arrow weights and styles, with bold being greater than solid and solid greater than dashed arrows.

A recent study by Danot (2015) also supports an equilibrium-based switch activation mechanism for the bacterial MalT STAND receptor. In this work, Danot found that the arm linking the WHD (ARC2 domain equivalent) and the sensor domains is involved in an intramolecular interaction with the NB domain to keep the protein in the closed/OFF state. Furthermore, he elegantly demonstrated that a MalT mutant locked in the ADP-bound/OFF state by cross-linking the arm and NB domain has a lower binding affinity for its inducer ligand, maltotriose, compared with MalT wild type. This result is very similar to our observations for L7 and the inactive L6 mutants. He further showed that the arm domain is also involved in ligand binding to the sensor domain and that these two functions (stabilization of the resting form and ligand binding) are mutually exclusive, suggesting that the arm is in an equilibrium between these two states. The intermediate ligand binding affinity of the wild-type MalT, between that of the locked closed state (low affinity) and the isolated arm sensor domain (high affinity), supports this hypothesis.

Here, we found that polymorphic sites in the TIR and NB can stabilize the OFF state of L7, suggesting a functional interaction between these regions. This may involve a direct physical interaction, as observed in MalT. Consistent with this, the polymorphic residues at positions 83, 85, and 86 are all surface exposed in the L6 TIR crystal structure, while C288 is also predicted to be surface exposed in a structural model of the L6 NB-ARC domain based on Apaf-1 (Supplemental Figures 9 and 10). In L7, the surface environments of the TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) regions are both mainly hydrophobic, whereas other L proteins contain only one hydrophobic region either in the TIR(L5, L10, L2) or in the NB(L6) domain regions (Supplemental Figures 10 and 11). Therefore, one structural interpretation of our functional data is that these two regions are in close contact in the inactive state of L proteins and the presence of hydrophobic patches in both the TIR and NB domain in L7 retains the protein in its OFF state more tightly than in L6 and the other L alleles, thus inhibiting its activation upon effector recognition. However, despite several attempts using Y2H and coimmunoprecipitation assays, we were not able to demonstrate a physical interaction between the isolated TIR and NB domains, which suggests a weak interaction or the need for an intact full-length NLR for optimal folding and intradomain interaction in this protein. Alternatively, this apparent functional interaction may be mediated indirectly, perhaps through separate and mutually exclusive interactions with other parts of the protein.

Interestingly, for all but the most active L6/L7 variants (L6 and L7FCY/SRR), which apparently led to a saturated level of signaling, the cell death phenotype induced by AvrL567 recognition is stronger than the phenotype induced by incorporation of the MHV autoactivating mutation (Figures 4 and 5A). Furthermore, the cell death phenotype induced by the presence of a MHV mutation is enhanced by the presence of the effector (Figure 5B). This suggests that the MHV mutation is less efficient in driving the protein toward the active state or in maintaining the active state than is effector recognition. Consistent with this, we previously found that although the autoactive flax M immune receptor containing an MHV mutation binds preferentially to ATP, corresponding to the ON state, it was also found bound to ADP (OFF state), albeit in much lower proportion (Williams et al., 2011). Mutation in the MHD motif also affects nucleotide binding of L6, leading to a decreased stability of the ADP-bound state, which is associated with autoactivity of the mutant protein (Figures 3B and 6). In contrast to MMHV, no enhanced binding to ATP was observed for L6MHV. It may be that the ATP-bound form of L6 is not sufficiently stable to be purified intact under our conditions. In the crystal structure of NLRC4, a mammalian NLR, the β-phosphate of the ADP molecule interacts with the conserved histidine in the winged helix domain, equivalent to that in the plant MHD motif, and interruption of this histidine/β-phosphate interaction also gives rise to an autoactive phenotype of NLRC4 (Hu et al., 2013). This is consistent with our data indicating that the autoactive L6MHV and MMHV NLR proteins show reduced ADP binding compared with the wild-type proteins. In the case of L7, a MHD/V mutation cannot drive the protein toward the ON state due to the constraints of the TIR and NB regions, which is demonstrated by the fact that L7MHV binds similar levels of ADP to L7 wild type (Figure 6). However, the quantitative difference between effector-dependent and -independent signaling in this system may explain why the C288R mutation apparently restored full function to L7 or L6SRR/FCY expressed in the presence of AvrL567 (Figure 4), but did not fully restore autoactivity to the L7MHV or L6MHV SRR/FCY (Figure 5). Under the model we propose, effector-dependent and -independent activation would occur via different mechanisms. The MHV mutation leads to reduced stability of the ADP-bound form through disruption of the interaction of the ADP β-phosphate with the histidine of the MHD motif, thereby enhancing the forward reaction of the equilibrium. On the other hand, effector recognition is envisaged to operate via stabilizing the ATP-bound form and reducing the reverse reaction. This can explain why the presence of the effector can further enhance signaling by the MHV mutants leading to a stronger cell death response (Figures 5 and 8), since the ON state of these mutants could still be recycled via ATP hydrolysis. To further test and validate this model, a key experiment will be to measure and compare the ATP hydrolysis rate of L6 and L7 in the presence or absence of the effector, as well as in a MHD/V mutant background.

Interestingly, a recent study from Slootweg et al. (2013) reported findings that are consistent with an equilibrium model. The authors demonstrated that an intramolecular interaction between the CC-NB-ARC and LRR domains of the potato (Solanum tuberosum) immune receptors Rx1 and Gpa2, expressed in trans, is weakened in the presence of their corresponding effectors. However, a mutation in the ARC2 domain at position 401 of Gpa2, which inhibits effector-dependent cell death activation, strengthens the CC-NB-ARC/LRR intramolecular interaction, and this stronger interaction does not seem to be disrupted by the presence of the effector. Similarly to L7, the Gpa2 R401Q mutant seems to be held in its inactive state by enhanced intradomain interactions, thus decreasing the pool of active protein available for effector recognition (with released intradomain interaction) ready to perceive the effector. An equilibrium switch model in this system is further supported by the observation that some CC-NB-ARC/LRR interaction is still observed in the presence of the effector (Slootweg et al., 2013).

On a similar note, Harris et al. (2013) identified four mutations around the nucleotide binding site of Rx that enhance the sensitivity of this receptor to respond to the poplar mosaic virus (Harris et al., 2013). Combining these four mutations in Rx induces a constitutive cell death that is dependent on an intact P-loop, leading the authors to suggest that the individual mutations each increase the propensity of Rx to become activated by favoring the ATP-bound/ON state, with the combination of these mutations leading to an excess of activated protein and thus inducing an effector-independent defense response. It would be interesting to compare the nucleotide binding activity of individual Rx mutants compared with the quadruple mutant and determine whether these sensitized Rx variants show enhanced interaction with the corresponding PVX coat protein ligand to test whether this NLR operates by a similar model to that we have proposed for L6/L7.

Similar to the L6/L7 case, Stirnweis et al. (2014) have recently shown that two residues in the ARC2 domain that are polymorphic between broad and narrow recognition spectrum alleles of the wheat powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis f. sp tritici) immune receptor PM3 also regulate the cell death strength of these alleles in a transient assay. Reciprocal changes of these two residues in “weak” or “strong” alleles result in a stronger or a milder cell death response, respectively, and can also extend the resistance spectrum of the weak Pm3f allele (Stirnweis et al., 2014). These observations suggest that the nature of polymorphic residues in the ARC2 domain can modify the equilibrium between the ON and OFF states of PM3 receptors in the absence of pathogen, similarly to the TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) regions of L6 and L7.

Some NLR proteins recognize the presence of pathogen effectors in an indirect manner, through the detection of host target modification induced by pathogen effectors. For instance, the Arabidopsis thaliana RPM1 and RPS2 activate resistance upon detection of the Arabidopsis RIN4 protein’s modification (phosphorylation and cleavage, respectively), mediated by bacterial effectors (Axtell and Staskawicz, 2003; Mackey et al., 2003). In both cases, RIN4 interacts with RPM1 and RPS2 in the absence of effector, which might stabilize the NLR proteins in their inactive states and thus push the equilibrium toward the OFF state. Upon infection, modifications of RIN4 might release the inhibition of RPM1 and RPS2 and, as a consequence, modify the equilibrium toward the ON state to activate downstream defense responses. Indeed, RPS2 is constitutively active in the absence of RIN4, but this activity is suppressed through interaction with RIN4.

Thus, we believe that the “equilibrium-based switch model” provides a useful framework for considering functional aspects of plant NLR proteins in general. However, given the mechanistic differences in the mode of action of NLRs (direct versus indirect recognition and single versus paired receptors), extending this model more generally will require detailed biochemical studies of a range of NLRs with diverse functional characteristics.

Altogether, the above examples illustrate the importance of achieving an appropriate balance between the inhibition of signaling activity in the absence of a trigger (i.e., an equilibrium favoring the OFF state in absence of pathogen effector) versus a sufficient accumulation of active receptor upon recognition of the effector (i.e., an equilibrium favoring the ON state) to trigger an appropriate resistance response. However, the question arises of why weaker resistance proteins with properties like L7 would be retained during evolution. For example, while a small number of wheat stem rust resistance genes provide levels of resistance similar to L6, the majority give incomplete resistance similar to L7 (McIntosh et al., 1995). Although immune receptors that are easily activated can respond very rapidly to the pathogen invasion, this might also have a fitness cost for the plant. In our equilibrium-based switch model, the ability of NLRs to respond rapidly and strongly upon effector detection can be correlated with a slight equilibrium shift toward the ON state in the absence of pathogen, which in turn may lead to weak constitutive defense signaling at a fitness cost for the plant. In the case of L7, the negative interaction between the TIR and NB domains forces the equilibrium toward the OFF state compared with other L receptors, but this comes at the cost of a reduced level of resistance. Thus, constraints on NLR protein evolution involve a balance between the effectiveness of the resistance response induced by ligand recognition and potential fitness costs due to low-level constitutive signaling in the absence of pathogens. Similar constraints are likely to apply to attempts to engineer immune receptors for enhanced disease resistance in crop plants (Harris et al., 2013; Chapman et al., 2014; Segretin et al., 2014).

METHODS

Plant Material, Flax Rust Strains, and Rust Inoculation

The origins and descriptions of the flax (Linum usitatissimum) lines and the flax rust (Melampsora lini) strain CH5F2-138 used in this study, as well as rust infection methods, are provided by Lawrence et al. (1981). Near-isogenic flax lines containing the L6 or L7 alleles backcrossed into var Bison have been described by Flor (1954). Transgenic W38 tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) expressing AvrL567-A was described by Bernoux et al. (2011b).

Vectors and Plasmid Construction

In planta transient expression plasmids and Y2H plasmids were constructed by Gateway cloning (GWY; Invitrogen). PCR products flanked by the attB sites were recombined into pDONR207 (Invitrogen) and then into corresponding destination vectors: pAM-PATpro35S:GWY-YFPv (Bernoux et al., 2008) and Gateway-compatible Y2H vectors based on pGADT7 (Clontech), which contains a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope sequence, downstream of the GAL4 AD domain, as previously described (Bernoux et al., 2011b). BD-AvrL567 was introduced into pGBT9 (Clontech) by restriction ligation (Dodds et al., 2006). Mutations were introduced by DpnI-mediated site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

For nucleotide binding assays, the pPICzA vector (Invitrogen) was modified to incorporate a 6Xhistidine tag and a cleavage site that can be recognized by the human rhinovirus 3C protease. NotI and SpeI sites were incorporated downstream of the protease cleavage site to facilitate NLR protein cloning. The entire 6Xhistidine-3C protease cleavage (6H3C)-containing fragment encoded MAHHHHHHSAALEVLFQGPAAA. This fragment was generated to contain an upstream BstB1 restriction site and a downstream ApaI restriction site. Both pPICzA and the 6H3C fragment were digested with BstBI/ApaI to facilitate cloning of 6Xhistidine-3C-Not1/Spe1 into the pPICzA vector, designated pP6H3C. cDNAs of L6 and L7 were then cloned into pP6H3C using the NotI/SpeI restriction sites. Additional residues were encoded in the reverse primers to include a C-terminal Strep II tag (SAWSHPQFEK) designed for further downstream protein purification if necessary. Therefore, L6 and L7 proteins were produced with an N-terminal 6XHis and C-terminal Strep II tag. All constructs were verified by sequencing. Details of constructs and primers are given in Supplemental Data Sets 1 and 2.

Transient Expression and Y2H Assays

Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells were grown for 36 h at 28°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing appropriate antibiotic selections. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in the infiltration medium (10 mM MgCl2 and 200 µM acetosyringone), adjusted to OD600 = 1, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Resuspended cells were infiltrated with a 1-mL needleless syringe into leaves of 3-week-old tobacco or Nicotiana benthamiana plants. Yeast transformation, using the HF7c yeast strain, and growth assays were performed as described in the Yeast Protocols Handbook (Clontech).

Immunoblot Analysis

Yeast protein extraction for immunoblot analysis was performed following a postalkaline extraction method (Kushnirov, 2000). Plant proteins were extracted by grinding two leaf discs collected 28 h after agroinfiltration in the loading buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Pall). Membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk and probed with 0.2 µg/mL anti-GFP mouse monoclonal antibodies (clones 7.1 and 13.1; Roche), followed by 1/20,000 dilution of goat anti-mouse HRP conjugate (Bio-Rad) for plant protein samples. Yeast protein samples were probed with 5 pg/mL anti-HA-HRP conjugate rat monoclonal antibodies (clone 3F10; Roche) or with 0.4 µg/mL anti-GAL4 DNA-BD rabbit antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by 1/20,000 dilution of HRP-goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Invitrogen). Protein labeling was detected with the SuperSignal West Femto chemiluminescence kit (Pierce). Membranes were stained with Red Ponceau for protein loading.

Protein Purification and Nucleotide Binding Assays

Histidine-tagged proteins were purified from total lysate of Pichia pastoris pellets (6 g) by NiA chromatography (Supplemental Figure 8), as previously described (Schmidt et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2011), except that 150 mL cultures were grown as opposed to the 100 mL described by Williams et al. (2011). Proteins were concentrated using centrifugal filter units (Millipore). Protein purification and nucleotide quantification assays were done as described by Williams et al. (2011). A bioluminescence assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to measure ATP levels. The supernatant of boiled purified protein samples following centrifugation at 12,000g was used directly in the ATP assay. For ADP measurements, ADP was first converted to ATP using pyruvate kinase, followed by ATP measurements and extrapolation back to ADP by comparison to the non-enzyme-linked ATP assay. Nucleotide occupancy was calculated according to the number of moles of ATP or ADP per mole of NLR protein and expressed as a percentage of molecules bound to ADP or ATP. To quantify the amount of NiA-purified R protein, 10 μL of protein, along with known concentrations of BSA, was separated by 10% acrylamide SDS-PAGE. Gels were placed in 35 mL of SYPRO Ruby stain and microwaved on high power for 30 s. Samples were gently shaken for 30 s, before another 30 s microwave treatment. Samples were then left to shake in SYPRO Ruby stain for 30 min in the dark before destaining in 10% ethanol and 7% acetic acid solution. Gels were imaged using Bio-Rad CHEMIDOC. A BSA standard curve was used to calculate NLR protein concentration, which typically ranged from 20 to 70 μg total protein per gram of wet cells.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL libraries under the following accession numbers: AY510102 (AvrL567), U27081 (L6), and AF093646 (L7).

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Phenotype comparison of rust-infected L6- and L7-carrying flax plants.

Supplemental Figure 2. L7F83S, L7C85Y, L7Y86R, and L7C288R mutants are not autoactive.

Supplemental Figure 3. Reciprocal mutations in the TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) regions of L7 and L6 have complementary effects on effector-dependent signaling activity.

Supplemental Figure 4. Immunoblot detection of L7 and L6 mutant proteins fused to YFP using anti-GFP antibodies.

Supplemental Figure 5. Cell death activity of L7MHV and L6MHV mutants is enhanced in the presence of the flax rust AvrL567 effector in tobacco.

Supplemental Figure 6. Cell death activity of L7MHV and L6MHV mutants is enhanced in the presence of the flax rust AvrL567 effector in N. benthamiana.

Supplemental Figure 7. Schematic representation of recombinant L6 and L7 proteins (29-1294) used for nucleotide binding studies.

Supplemental Figure 8. SYPRO Ruby stain and immunoblot analysis of L6 and L7 mutant proteins purified by NiA affinity chromatography.

Supplemental Figure 9. L6 S83, R85, and R86 residues are surface-exposed.

Supplemental Figure 10. Surface characteristics of the TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) regions in L6 and L7.

Supplemental Figure 11. Sequences of TIR(83,85,86) and NB(288) regions in various L alleles.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Constructs used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set 2. Primer details.

Acknowledgments

M.B. was a recipient of an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE130101292). The research was also supported by ARC Discovery Project DP120100685 awarded to B.K., J.G.E., and P.N.D. B.K. is a National Health and Medical Research Council Research Fellow (1003325). We thank Stella Cesari for critical reading of the manuscript and Anthony Ashton for ongoing interest and useful suggestions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.B., P.N.D., P.A.A., and J.G.E. designed the research. M.B., H.B., K.N., G.J.L., S.J.W., X.Z., and C.C. performed experiments. M.B., H.B., S.J.W., J.G.E., G.J.L., B.K., P.A.A., P.N.D., X.Z., and C.C. analyzed data. M.B., P.N.D., and H.B. wrote the article. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Glossary

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- Y2H

yeast two-hybrid

- NiA

nickel affinity

References

- Axtell M.J., Staskawicz B.J. (2003). Initiation of RPS2-specified disease resistance in Arabidopsis is coupled to the AvrRpt2-directed elimination of RIN4. Cell 112: 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Q., Riedl S.J., Shi Y. (2005). Structure of Apaf-1 in the auto-inhibited form: a critical role for ADP. Cell Cycle 4: 1001–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendahmane A., Farnham G., Moffett P., Baulcombe D.C. (2002). Constitutive gain-of-function mutants in a nucleotide binding site-leucine rich repeat protein encoded at the Rx locus of potato. Plant J. 32: 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent A.F., Kunkel B.N., Dahlbeck D., Brown K.L., Schmidt R., Giraudat J., Leung J., Staskawicz B.J. (1994). RPS2 of Arabidopsis thaliana: a leucine-rich repeat class of plant disease resistance genes. Science 265: 1856–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernoux M., Ellis J.G., Dodds P.N. (2011a). New insights in plant immunity signaling activation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14: 512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernoux M., Timmers T., Jauneau A., Brière C., de Wit P.J., Marco Y., Deslandes L. (2008). RD19, an Arabidopsis cysteine protease required for RRS1-R-mediated resistance, is relocalized to the nucleus by the Ralstonia solanacearum PopP2 effector. Plant Cell 20: 2252–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernoux M., Ve T., Williams S., Warren C., Hatters D., Valkov E., Zhang X., Ellis J.G., Kobe B., Dodds P.N. (2011b). Structural and functional analysis of a plant resistance protein TIR domain reveals interfaces for self-association, signaling, and autoregulation. Cell Host Microbe 9: 200–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S., Stevens L.J., Boevink P.C., Engelhardt S., Alexander C.J., Harrower B., Champouret N., McGeachy K., Van Weymers P.S., Chen X., Birch P.R., Hein I. (2014). Detection of the virulent form of AVR3a from Phytophthora infestans following artificial evolution of potato resistance gene R3a. PLoS One 9: e110158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier S.M., Hamel L.P., Moffett P. (2011). Cell death mediated by the N-terminal domains of a unique and highly conserved class of NB-LRR protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24: 918–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl J.L., Jones J.D. (2001). Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411: 826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danot O. (2015). How ‘arm-twisting’ by the inducer triggers activation of the MalT transcription factor, a typical signal transduction ATPase with numerous domains (STAND). Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 3089–3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P.N., Lawrence G.J., Catanzariti A.M., Ayliffe M.A., Ellis J.G. (2004). The Melampsora lini AvrL567 avirulence genes are expressed in haustoria and their products are recognized inside plant cells. Plant Cell 16: 755–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P.N., Lawrence G.J., Catanzariti A.M., Teh T., Wang C.I., Ayliffe M.A., Kobe B., Ellis J.G. (2006). Direct protein interaction underlies gene-for-gene specificity and coevolution of the flax resistance genes and flax rust avirulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 8888–8893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P.N., Rathjen J.P. (2010). Plant immunity: towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11: 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J.A., Bergstralh D.T., Wang Y., Willingham S.B., Ye Z., Zimmermann A.G., Ting J.P. (2007). Cryopyrin/NALP3 binds ATP/dATP, is an ATPase, and requires ATP binding to mediate inflammatory signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 8041–8046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J.G., Lawrence G.J., Luck J.E., Dodds P.N. (1999). Identification of regions in alleles of the flax rust resistance gene L that determine differences in gene-for-gene specificity. Plant Cell 11: 495–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustin B., Lartigue L., Bruey J.M., Luciano F., Sergienko E., Bailly-Maitre B., Volkmann N., Hanein D., Rouiller I., Reed J.C. (2007). Reconstituted NALP1 inflammasome reveals two-step mechanism of caspase-1 activation. Mol. Cell 25: 713–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H.H. (1954). Seed-flax improvement. III. Flax rust. Adv. Agron. 6: 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Frost D., Way H., Howles P., Luck J., Manners J., Hardham A., Finnegan J., Ellis J. (2004). Tobacco transgenic for the flax rust resistance gene L expresses allele-specific activation of defense responses. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 17: 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M.R., Godiard L., Straube E., Ashfield T., Lewald J., Sattler A., Innes R.W., Dangl J.L. (1995). Structure of the Arabidopsis RPM1 gene enabling dual specificity disease resistance. Science 269: 843–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Growney J.D., Dietrich W.F. (2000). High-resolution genetic and physical map of the Lgn1 interval in C57BL/6J implicates Naip2 or Naip5 in Legionella pneumophila pathogenesis. Genome Res. 10: 1158–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C.J., Slootweg E.J., Goverse A., Baulcombe D.C. (2013). Stepwise artificial evolution of a plant disease resistance gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 21189–21194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howles P., Lawrence G., Finnegan J., McFadden H., Ayliffe M., Dodds P., Ellis J. (2005). Autoactive alleles of the flax L6 rust resistance gene induce non-race-specific rust resistance associated with the hypersensitive response. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18: 570–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., et al. (2013). Crystal structure of NLRC4 reveals its autoinhibition mechanism. Science 341: 172–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inohara N., Koseki T., del Peso L., Hu Y., Yee C., Chen S., Carrio R., Merino J., Liu D., Ni J., Núñez G. (1999). Nod1, an Apaf-1-like activator of caspase-9 and nuclear factor-kappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 14560–14567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inohara N., Nuñez G. (2003). NODs: intracellular proteins involved in inflammation and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3: 371–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.R., Mayo G.M.E. (1990). A compendium on host genes in flax conferring resistance to flax rust. Plant Breed. 104: 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Jones J.D., Dangl J.L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444: 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.E., Du F., Fang M., Wang X. (2005). Formation of apoptosome is initiated by cytochrome c-induced dATP hydrolysis and subsequent nucleotide exchange on Apaf-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 17545–17550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasileva K.V., Dahlbeck D., Staskawicz B.J. (2010). Activation of an Arabidopsis resistance protein is specified by the in planta association of its leucine-rich repeat domain with the cognate oomycete effector. Plant Cell 22: 2444–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirov V.V. (2000). Rapid and reliable protein extraction from yeast. Yeast 16: 857–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence G.J., Finnegan E.J., Ayliffe M.A., Ellis J.G. (1995). The L6 gene for flax rust resistance is related to the Arabidopsis bacterial resistance gene RPS2 and the tobacco viral resistance gene N. Plant Cell 7: 1195–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence G.J., Mayo G.M.E., Shepherd K.W. (1981). Interactions between genes controlling pathogenicity in the flax rust fungus. Phytopathology 71: 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Luck J.E., Lawrence G.J., Dodds P.N., Shepherd K.W., Ellis J.G. (2000). Regions outside of the leucine-rich repeats of flax rust resistance proteins play a role in specificity determination. Plant Cell 12: 1367–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasik-Shreepaathy E., Slootweg E., Richter H., Goverse A., Cornelissen B.J., Takken F.L. (2012). Dual regulatory roles of the extended N terminus for activation of the tomato MI-1.2 resistance protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 25: 1045–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey D., Belkhadir Y., Alonso J.M., Ecker J.R., Dangl J.L. (2003). Arabidopsis RIN4 is a target of the type III virulence effector AvrRpt2 and modulates RPS2-mediated resistance. Cell 112: 379–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa T., et al. (2011). Coiled-coil domain-dependent homodimerization of intracellular barley immune receptors defines a minimal functional module for triggering cell death. Cell Host Microbe 9: 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquenet E., Richet E. (2007). How integration of positive and negative regulatory signals by a STAND signaling protein depends on ATP hydrolysis. Mol. Cell 28: 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh R.A., Wellings C.R., Park R.F. (1995). Wheat Rusts, an Atlas of Resistance Genes. (Australia: CSIRO Publications; ). [Google Scholar]

- Michael Weaver L., Swiderski M.R., Li Y., Jones J.D. (2006). The Arabidopsis thaliana TIR-NB-LRR R-protein, RPP1A; protein localization and constitutive activation of defence by truncated alleles in tobacco and Arabidopsis. Plant J. 47: 829–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindrinos M., Katagiri F., Yu G.L., Ausubel F.M. (1994). The A. thaliana disease resistance gene RPS2 encodes a protein containing a nucleotide-binding site and leucine-rich repeats. Cell 78: 1089–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motlagh H.N., Wrabl J.O., Li J., Hilser V.J. (2014). The ensemble nature of allostery. Nature 508: 331–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura Y., Inohara N., Benito A., Chen F.F., Yamaoka S., Nunez G. (2001). Nod2, a Nod1/Apaf-1 family member that is restricted to monocytes and activates NF-kappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 4812–4818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi D., DeYoung B.J., Innes R.W. (2012). Structure-function analysis of the coiled-coil and leucine-rich repeat domains of the RPS5 disease resistance protein. Plant Physiol. 158: 1819–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi S., et al. (2010). Crystal structure of the Caenorhabditis elegans apoptosome reveals an octameric assembly of CED-4. Cell 141: 446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rairdan G.J., Moffett P. (2006). Distinct domains in the ARC region of the potato resistance protein Rx mediate LRR binding and inhibition of activation. Plant Cell 18: 2082–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravensdale M., Bernoux M., Ve T., Kobe B., Thrall P.H., Ellis J.G., Dodds P.N. (2012). Intramolecular interaction influences binding of the Flax L5 and L6 resistance proteins to their AvrL567 ligands. PLoS Pathog. 8: e1003004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubold T.F., Wohlgemuth S., Eschenburg S. (2009). A new model for the transition of APAF-1 from inactive monomer to caspase-activating apoptosome. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 32717–32724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubold T.F., Wohlgemuth S., Eschenburg S. (2011). Crystal structure of full-length Apaf-1: how the death signal is relayed in the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Structure 19: 1074–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl S.J., Li W., Chao Y., Schwarzenbacher R., Shi Y. (2005). Structure of the apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 bound to ADP. Nature 434: 926–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S.A., Williams S.J., Wang C.I., Sornaraj P., James B., Kobe B., Dodds P.N., Ellis J.G., Anderson P.A. (2007). Purification of the M flax-rust resistance protein expressed in Pichia pastoris. Plant J. 50: 1107–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segretin M.E., Pais M., Franceschetti M., Chaparro-Garcia A., Bos J.I., Banfield M.J., Kamoun S. (2014). Single amino acid mutations in the potato immune receptor R3a expand response to Phytophthora effectors. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27: 624–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slootweg E.J., Spiridon L.N., Roosien J., Butterbach P., Pomp R., Westerhof L., Wilbers R., Bakker E., Bakker J., Petrescu A.J., Smant G., Goverse A. (2013). Structural determinants at the interface of the ARC2 and leucine-rich repeat domains control the activation of the plant immune receptors Rx1 and Gpa2. Plant Physiol. 162: 1510–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrenner A.D., Goritschnig S., Staskawicz B.J. (2015). Recognition and activation domains contribute to allele-specific responses of an Arabidopsis NLR receptor to an oomycete effector protein. PLoS Pathog. 11: e1004665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirnweis D., Milani S.D., Jordan T., Keller B., Brunner S. (2014). Substitutions of two amino acids in the nucleotide-binding site domain of a resistance protein enhance the hypersensitive response and enlarge the PM3F resistance spectrum in wheat. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27: 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiderski M.R., Birker D., Jones J.D. (2009). The TIR domain of TIR-NB-LRR resistance proteins is a signaling domain involved in cell death induction. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takken F.L., Albrecht M., Tameling W.I. (2006). Resistance proteins: molecular switches of plant defence. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9: 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takken F.L., Goverse A. (2012). How to build a pathogen detector: structural basis of NB-LRR function. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15: 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tameling W.I., Elzinga S.D., Darmin P.S., Vossen J.H., Takken F.L., Haring M.A., Cornelissen B.J. (2002). The tomato R gene products I-2 and MI-1 are functional ATP binding proteins with ATPase activity. Plant Cell 14: 2929–2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tameling W.I., Vossen J.H., Albrecht M., Lengauer T., Berden J.A., Haring M.A., Cornelissen B.J., Takken F.L. (2006). Mutations in the NB-ARC domain of I-2 that impair ATP hydrolysis cause autoactivation. Plant Physiol. 140: 1233–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C., Schwieters C.D., Clore G.M. (2007). Open-to-closed transition in apo maltose-binding protein observed by paramagnetic NMR. Nature 449: 1078–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda H., Yamaguchi Y., Sano H. (2006). Direct interaction between the tobacco mosaic virus helicase domain and the ATP-bound resistance protein, N factor during the hypersensitive response in tobacco plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 61: 31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Biezen E.A., Jones J.D. (1998). The NB-ARC domain: a novel signalling motif shared by plant resistance gene products and regulators of cell death in animals. Curr. Biol. 8: R226–R227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ooijen G., Mayr G., Kasiem M.M., Albrecht M., Cornelissen B.J., Takken F.L. (2008). Structure-function analysis of the NB-ARC domain of plant disease resistance proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 59: 1383–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.I., et al. (2007). Crystal structures of flax rust avirulence proteins AvrL567-A and -D reveal details of the structural basis for flax disease resistance specificity. Plant Cell 19: 2898–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.F., Ji J., El-Kasmi F., Dangl J.L., Johal G., Balint-Kurti P.J. (2015). Molecular and functional analyses of a maize autoactive NB-LRR protein identify precise structural requirements for activity. PLoS Pathog. 11: e1004674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitham S., Dinesh-Kumar S.P., Choi D., Hehl R., Corr C., Baker B. (1994). The product of the tobacco mosaic virus resistance gene N: similarity to toll and the interleukin-1 receptor. Cell 78: 1101–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.J., Sornaraj P., deCourcy-Ireland E., Menz R.I., Kobe B., Ellis J.G., Dodds P.N., Anderson P.A. (2011). An autoactive mutant of the M flax rust resistance protein has a preference for binding ATP, whereas wild-type M protein binds ADP. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24: 897–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.J., et al. (2014). Structural basis for assembly and function of a heterodimeric plant immune receptor. Science 344: 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]