Abstract

Family-centered care (FCC) for sick newborns is emerging as a paradigmatic shift in the practice of facility-based newborn care. It seeks to transforming a provider-centered model into a client-centered one and thus build a new therapeutic alliance. FCC is the cornerstone of continuum of care, imparting caregiving competencies to parents/caregivers both within institutions as well as after the discharge. This has potential gains for the newborn, family members, and facility-level staff. The initial model piloted in tertiary-care settings is now undergoing translation at five sites across the country; the outcomes are keenly awaited.

Keywords: Capacity building, empowerment, Family centered care for newborn, FCC, Sick newborn care by parent attendant

Introduction

With improvements in neonatal survival rate, there is increasing attention and emphasis on improving quality of neonatal care. A key strategy toward that end is improving clinical care at facilities for sick neonates. Facility-based neonatal care (FBNC) entails institutionalized care of sick neonates. The National Health Mission (NHM) has made significant investments to this end in setting up Special Newborn Care Units (SNCUs) at district levels.

Hospitalization of a sick neonate separates the baby from her/his mother and family. Typically neonatal units have focused upon technology-driven, provider-centered care for sick neonates, where parental/family participation in caring and decision-making regarding their own babies is severely limited.(1) The psychosocial needs of babies and families remain unaddressed. While neonatal survival may be positively impacted upon, the current model of care is not adequately client/family centered.(2) indeed, there is sufficient evidence that they lead to anxiety and stress among parents and family members.

Family-centered care (FCC) for sick newborns seeks to develop and nurture the family's role in partnership with the clinical care delivery team of doctors and nurses. FCC promotes and nurtures a unique milieu in the nursery or SNCUs by actively involving parents in caregiving to their babies. FCC creates an environment that is responsive to the family-identified needs; culturally sensitive; and above all, provides a setting in which family is empowered and encouraged to support care for their baby as the constant caretaker from admission onward until discharge.(3) This also prepares them for better handling and care of the baby at home after discharge.

Conceptual Framework of FCC

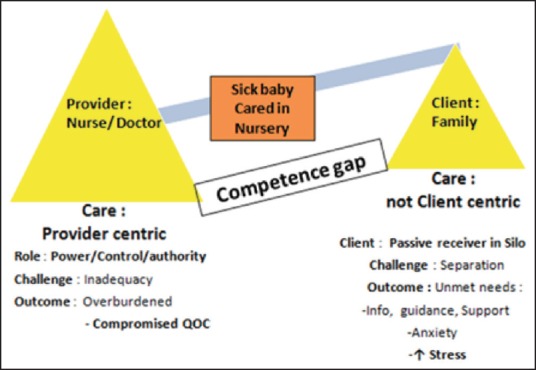

The conventional model for care of a sick Newborn [Figure 1] involves delivery of care primarily by the nurse or doctor only. There is an imbalance between the provider and the family and a true partnership does not exist. The disconnect created by:

Figure 1.

Conventional model for care of sick newborn

A competence gap between skilled doctors and nurses and the “unskilled” parents/family members.

Parents and family members face separation, fear, anxiety, and stress that are associated with sickness and hospitalization of their little ones.

Free visitation of family attendants is often not allowed in the nurseries, leaving the parent attendant waiting outside (in a “silo”) with their sick baby inside the nursery.

The imbalance is furthered by near-universal human resource shortages of nurses and doctors leaving them overburdened and potentially compromising the quality of care. The authority, control, and power exercised by the providers result in unmet needs of information, guidance, and support to the parents who merely become passive receivers rather than partners.

What is FCC?

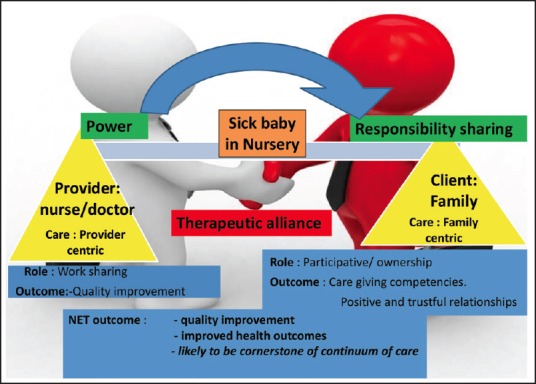

FCC marks a paradigmatic shift in neonatal care where family members are accorded an active participatory role through their involvement in the care of their babies that is achieved through learned and acquired competencies. While the care provider continues to be in charge, a healthy therapeutic alliance develops between the provider and the parent/family member with a sharing of work and care beyond exercise of power, control or authority by the nurse/doctor. The desired outcome is a co-construction of care that results in improvement in the quality of care and building of positive entrustment among the two sides and overall improved clinical outcomes. This is likely to be the cornerstone of continuum of care for the baby at home after discharge from the facility [Figure 2]. The principles of FCC are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Family-centered care (FCC): A paradigm shift

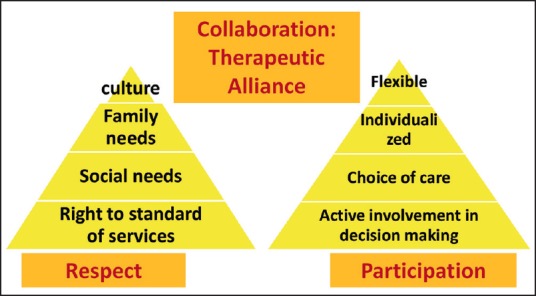

Figure 3.

Principles of family-centered care (FCC)

Advantages of FCC

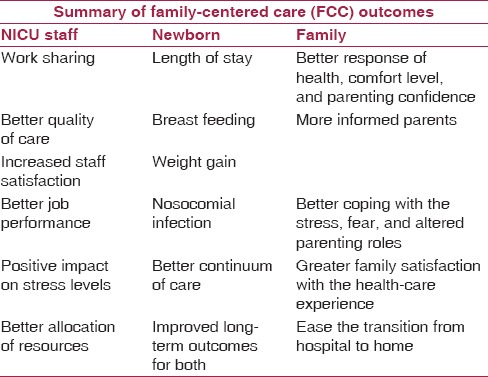

The practice of FCC is being widely accepted across nurseries for a range of advantages that it provides. Favorable outcomes pertain to all three stakeholders namely: the baby (patient), the family and the nursery staff. The positive impact on the sick neonate has been evident from better weight gains, shorter length of hospital stay, and higher breast feeding rates before the discharge.(4,5,6,7,8,9) Impact on the family has been observed in form of better informed and confident parents who are able to cope better with stress or fear and altered parenting roles. All this culminates in overall better family satisfaction with the health care experience. There is enhanced bonding between the parents and their baby and an ease of transfer from hospital to home. Because of work sharing, the impact on the nursery staff has been in terms of delivery of better quality of care with better staff satisfaction and positive impact on stress levels. This has been shown to be associated with better allocation of resources. Table 1 presents a summary of FCC outcomes.

Table 1.

Summary of family-centered care (FCC) outcomes

The Evidence

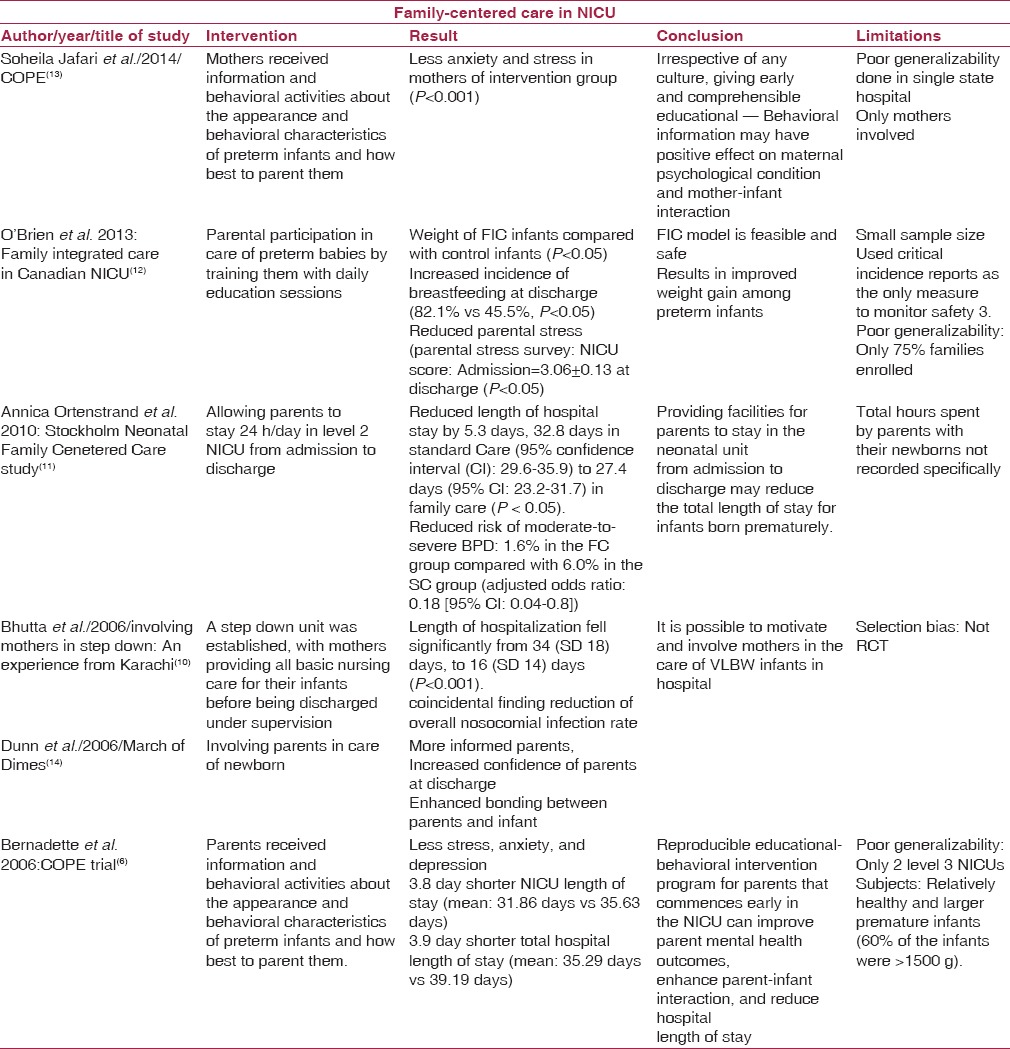

Several studies have evaluated the impact of various interventions within the ambit of FCC and has shown improved health outcomes for neonates and families. Bhutta et al.(10) allowed free visitation of mothers in step-down area for care of stable very low birth weight (VLBW) infants, and found that this was associated with reduced duration of stay and decreased nosocomial infection rates. Parents in creating opportunities for parent empowerment (COPE trial)(6) received written and audio-taped information and performed behavioral activities to parent their preterm babies. This intervention reduced their duration of hospitalization. In the Stockholm neonatal FCC study, parents were allowed to stay for 24 h and this reduced total hospital stay duration in preterm neonates admitted to a level 2 neonatal intensive-care unit (NICU).(11) O’Brien et al.(12) developed a Family Integrated Care model for parental participation in care of preterm babies by training them with daily education sessions that improved breast feeding rates and weight gain. Table 2 presents a summary of finding from some of these key studies.

Table 2.

Family-centered care (FCC) in sick neonatal care units/neonatal intensive-care unit (SNCU/NICU)

Our Experience

We conducted a randomized control trial (RCT) at the Post Graduate Institute, RML Hospital, New Delhi, during 2010-2012 with an aim to adapt principles of FCC to partly overcome the problem of human resource constraints and improve neonatal outcomes in a setting of a tertiary referral neonatal unit. We inducted accompanying parent–attendant of sick neonates to participate in delivery of care to their sick neonates in addition to the standard care provided by nurses and doctors. This was achieved through indigenous development of a culturally sensitive audiovisual training module.

A simplified audiovisual training tool was prepared with multidisciplinary technical inputs from a neonatologist, a community medicine specialist, a psychologist, nursing, and a Hindi-language expert. Preimplementation testing was done by administering it to parents with varied religious, language, socioeconomic, and educational backgrounds. Feedback inputs were incorporated; tool was readministered and checked for comprehensibility and clarity, till the experts finalized for implementation after consensus. The objective was to aware, educate, train, and build capacities of accompanying parent attendants in the domains of personal hygiene, hand washing, identification of danger signs, reporting of adverse events and feeding and kangaroo mother care (KMC) of low birth weight sick newborns. We documented impact of this intervention on various neonatal outcomes. We found no increase in infection rate but better exclusive breast feeding rates (prior to discharge). We found this intervention as feasible, well accepted, and safe.

Piloting and Scaling Up

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, has recently approved the adaptation and introduction of FCC in the public health services, and this initiative is supported by the Norway India Partnership Initiative under United Nations Development Programme (NIPI-UNDP) newborn project. Five demonstration sites at district SNCUs have been set up: Alwar (Rajasthan), Raisen (Madhya Pradesh), Hoshangabad (Madhya Pradesh), Jharsuguda (Odisha), and Nalanda (Bihar). The translation and adaptation process has been envisaged in the following given manner:

Improving quality of Facility Based Newborn Care (FBNC) through FCC, as an approach to provide individualized care by the parent to each baby in addition to standard care as provided by nurses and doctors.

Addressing unmet psychosocial needs of the family and developmental needs of the sick neonate by increasing parental involvement in caregiving throughout the period of hospitalization and working with families to facilitate the discharge process; parents emerge from the NICU/Special Newborn Care Units (SNCUs) experience with better care-giving competencies.

The practice of FCC is likely to be the cornerstone of providing continuity of care at home after discharge.

The parent-attendants will be trained in hand-washing skills, providing basic nursing and developmentally supportive care to their babies, keeping their babies warm, technique of breast feeding and assisted feeding, Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC), preparation for discharge and recognition of danger signs.

Concluding Comments

FCC is a strategic low-cost innovation that is piloted for care of sick newborns in resource-constrained community healthcare facility settings. While this practice favorably impacts health outcomes of neonates as well as addresses unmet psychosocial needs of the family of the hospitalized neonate, it also has the potential to compensate for human resource shortages in low and middle income countries (LMIC) like ours. The experience from these pilot sites is keenly awaited by neonatologists, nursing professionals, health service planners, and child health researchers.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Obeidat HM, Bond EA, Callister LC. The parental experience of having an infant in the newborn intensive care unit. J Perinat Educ. 2009;18:23–9. doi: 10.1624/105812409X461199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison H. The principles of family-centered neonatal care. Pediatrics. 1993;92:643–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: A conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1087–110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsythe P. New practices in the transitional care center improve outcomes for babies and their families. J Perinatol. 1998;18:S13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jotzo M, Poets CF. Helping parents cope with the trauma of premature birth: An evaluation of a trauma-preventive psychological intervention. Pediatrics. 2005;115:915–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melnyk BM, Feinstein N, Alpert-Gillis L, Fairbanks E, Grean HF, Sinkin RA, et al. Reducing premature infants’ length of stay and improving parents’ mental health outcomes with the Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) neonatal intensive care unit program: A randomized, clinical trial. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1414–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shields-Poë D, Pinelli J. Variables associated with parental stress in neonatal intensive care units. Neonatal Netw. 1997;16:29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Riper M. Family-provider relationships and well-being in families with preterm infants in the NICU. Heart Lung. 2001;30:74–84. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.110625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee on Hospital Care; American Academy of Pediatrics. Family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2003;112:691–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhutta ZA, Khan I, Salat S, Raza F, Ara H. Reducing length of stay in hospital for very low birthweight infants by involving mothers in a stepdown unit: An experience from Karachi (Pakistan) BMJ. 2004;329:1151–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortenstrand A, Westrup B, Broström EB, Sarman I, Akerstörm S, Brune T, et al. The Stockholm Neonatal Family Centered Care Study: Effects on length of stay and infant morbidity. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e278–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien K, Bracht M, Macdonell K, McBride T, Robson K, O’leary L, et al. A pilot cohort analytic study of Family Integrated Care in a Canadian neonatal intensive care unit. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(Suppl 1):S12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-S1-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mianaei SJ, Karahroudy FA, Rassouli M, Tafreshi MZ. The effect of Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment program on maternal stress, anxiety, and participation in NICU wards in Iran. Iranian J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19:94–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn MS, Reilly MC, Johnston AM, Hoopes RD, Jr, Abraham MR. Development and dissemination of potentially better practices for the provision of family-centered care in neonatology: The family-centered care map. Pediatrics. 2006;118(Suppl 2):S95–107. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0913F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]