Introduction

Urban population in India has increased from 17-31.16% between 1951 and 2011.(1) Transport sector in India is an extensive system comprising different modes of transport, but road transport is the dominant mode playing an important role in conveyance of goods and passengers and linking the centers of production, consumption and distribution. Road transport accounted for 4.7% of India's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2010-11.(2) Although essential for mobility, trade, economic development and growth, integration and social inclusion, there are negative impacts of transportation as well especially that of energy intensive transport.

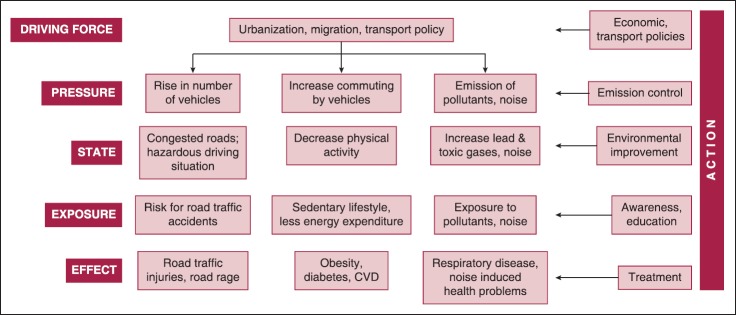

The objective of this paper is to review the multiple impacts on health as a result of road transport in urban areas. A review of literature was done for publications related to the topic focusing on the last 10 years. Sources included Pubmed, Google scholar, WHO website, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, Transport Research Wing, Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. Government of India, National Crime Record Bureau, Central Pollution Control Board Government of India etc. We used a health and environment cause-effect framework [Figure 1], the DPSEEA framework (Driving forces, Pressures, State, Exposures, health Effects and Actions)(3) which is a descriptive representation of the way in which various driving forces generate pressures that affect the state of the environment and ultimately human health, through the various exposure pathways by which people come into contact with the environment.(3) The framework takes account of the fact that various factors responsible for health and environment problems may be associated with such driving forces as population growth, urbanization, economic development, technological change, and to the policies underlying them. “Pressure” may be exerted on the environment which cause development sectors to generate various types of outputs (for example in the form of pollutant emissions), causing the “state” (quality) of the environment to be degraded through the dispersal and accumulation of pollutants in the environment such as air, soil, water and food. People may become “exposed” to potential hazards in the environment when they come into direct contact with these pollutants through breathing, drinking or eating. A variety of health effects may subsequently occur, ranging from minor, subclinical effects to illness and death depending on the intrinsic harmfulness of the pollutant, the severity and intensity of exposure and the susceptibility of the individuals exposed. Various actions can be implemented at different points of the framework and may take a variety of forms, including policy development, standard setting, technical control measures, health education or treatment of people with diseases.

Figure 1.

Effects of road transport on health: DPSEEA framework

Health effects

Transport access is critical for inclusive growth, economic development leading to rising demand for road transport. In 2009-10, road network in the country carried 85.2% of the total passenger movement by roads and railways put together, and 62.9% for freight transport.(4)

There has been a gradual change in the environment and an increase in the number of cars, emission of pollutants and noise emission have been documented over the years leading to numerous health consequences described below.

Road traffic accidents

The total number of registered motor vehicles in India increased from about 0.3 million in 1951 and 21.4 million in 1991 to about 142 million in 2011.(2) Registered vehicles grew at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 9.9% between 2001 and 2011. At this growth rate, the number of vehicles double every 6-7 years. The 53 million-plus cities as on 31st March 2011 accounted for 39.7 million registered vehicles. Among these, Delhi with 72.3 lakh vehicles, had the largest number, followed by Bengaluru (37.9 lakh), Chennai (34.6 lakh), Hyderabad (30.3 lakh) and Pune (20.9 lakh).(2) These five cities accounted for half (49.3%) of the total vehicles in the 53 million-plus cities. The fleet size in nearly all public transport undertakings has actually declined rather than increase to meet the increasing demands of transportation; and the use of personalized modes especially two wheelers has increased at the rate of 12% per annum in last two decades.(4) All these factors exert a tremendous pressure on the environment. To make the situation worse, most major roads and junctions in Indian cities are heavily encroached upon by parked vehicles, roadside hawkers and pavement dwellers.

The increase in car density in urban areas gives rise to a state of volatile environment, conflicts between cars and pedestrians. Exposure to such hazardous situations leads to disastrous and sometimes fatal effects on the population due to road traffic accidents, road rage, etc. Lack of footpaths, service lanes, cycle tracks and traffic calming measures to reduce speed, where non-motorized mode of transport blend with motorized traffic, increase the risk of accidents and their severity.(5) The number of people injured in accidents increased threefold from 13-42 per lakh population between 1970 and 2011. Reported accidents and injuries in government reports are likely to be underestimates because mild injuries are more common and don’t get reported. A population-based study from Hyderabad estimated an annual incidence of road traffic crash as a pedestrian or motorized two vehicle user using three month recall period at 2288 per 100,000 population and that of non-fatal road traffic injury (RTI) at 1931 per 100,000 population.(6) In India, it was estimated that the ratios between deaths, injuries requiring hospital treatment and minor injuries was 1:15:70.(7) RTAs affected mainly the people of productive age group, predominantly male(8) In India, the largest share (37%) of ‘accidental deaths’ due to unnatural causes is accounted for by road accidents in age group 30 to 44 years, 47.2% of deaths are due to traffic accidents.(9)

Air pollution

Air pollution is a well-known environmental risk to health. Vehicular emissions depend on age of vehicle, emission rate of different vehicle categories. With deteriorating mass transport services and increasing personalized motor vehicle use, vehicular emission is assuming serious dimensions in most Indian cities. Nearly 20% of passenger transport emission is by private automobiles although they only contribute 4% total passenger transport activity in Indian cities.(10)

Urban residents exposed to traffic pollution are at potentially higher risk of health effects from exposure to carcinogenic poly-aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) compounds.(11) Studies show that PAH ratio decreases significantly as a function of distance from the road.(12) The new (2005) guidelines by World Health Organization (WHO)(13) recommend revised limits for the concentration of selected air pollutants — particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide. These guidelines are much lower than the standards set by the National Ambient Air Standard prescribed by Central Pollution Control Board, India.(14) However, measured levels of these in Indian cities were found to be unsatisfactory, largely because of high levels respirable suspended PM. Their levels were as high as 10 times in some cities like Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai.(15) Contribution of automobiles in total air pollution is reported between 40–80%. For Delhi's ambient air quality, contribution of transport sector was estimated as high as 72%.(16)

Noise pollution

Community noise includes road, rail and air traffic, industries, construction and public works. It is caused mainly by traffic and alongside densely travelled roads equivalent sound pressure levels for 24 hour can reach 75-80dB. Prevalence of hearing loss is more in workers exposed to higher road traffic noise compared to those less exposed.(17) Indian studies have shown that vehicular traffic contributes significantly to noise pollution and annoyance in urban areas.(18,19,20) High noise levels interfere with speech and communication, decrease learning ability and scholastic performance. In the first half of night, exposure to road traffic noise chronically impaired cortisol regulation which correlated with disturbance of sleep, impaired concentration and memory.(21) Road traffic noise exposure was found associated with disturbed sleep, headache, hypertension, other cardiovascular diseases, especially in elderly persons.(22,23,24,25) Individuals exposed to road traffic noise had poor perception of their health; while another study of residents of quieter areas had higher health related quality of life scores compared to those living in noisy areas.(26,27)

Guidelines by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), New Delhi, India suggest that noise levels should not exceed 75 dB in daytime and 70 dB during night in industrial areas, while the corresponding levels for commercial area are 65 dB in day and 55 dB in night. In residential areas noise levels should not exceed 55 dB in day and 45 dB at night; corresponding values for silence zones in day time is 50 dB and 40 dB at night.(28) However in a study undertaken by National Environmental Engineering Research Institute, Nagpur revealed that noise levels in residential, commercial and industrial areas, and silent zones of Delhi and other cities far exceeded the standards prescribed by CPCB. The average noise level in Delhi was 80 dB, which is more than the recommended value, that is 55 dB. Another Indian study in Asanasol found that at all locations of data collection ambient noise levels were above the prescribed guideline values.(29)

Physical inactivity

Poor availability of footpaths and cycle lanes acts as disincentive to active transport, also pedestrian and people on two wheelers are most vulnerable to injuries in case of road traffic accident. This increases the number of motorized vehicles usage. A study estimated that lack of physical activity can be held responsible for 3.3% deaths and 19 million Disability Adjusted Life years (DALYs) worldwide, through diseases including ischaemic heart disease, diabetes, colon cancer, stroke, and breast cancer.(30)

Other health effects

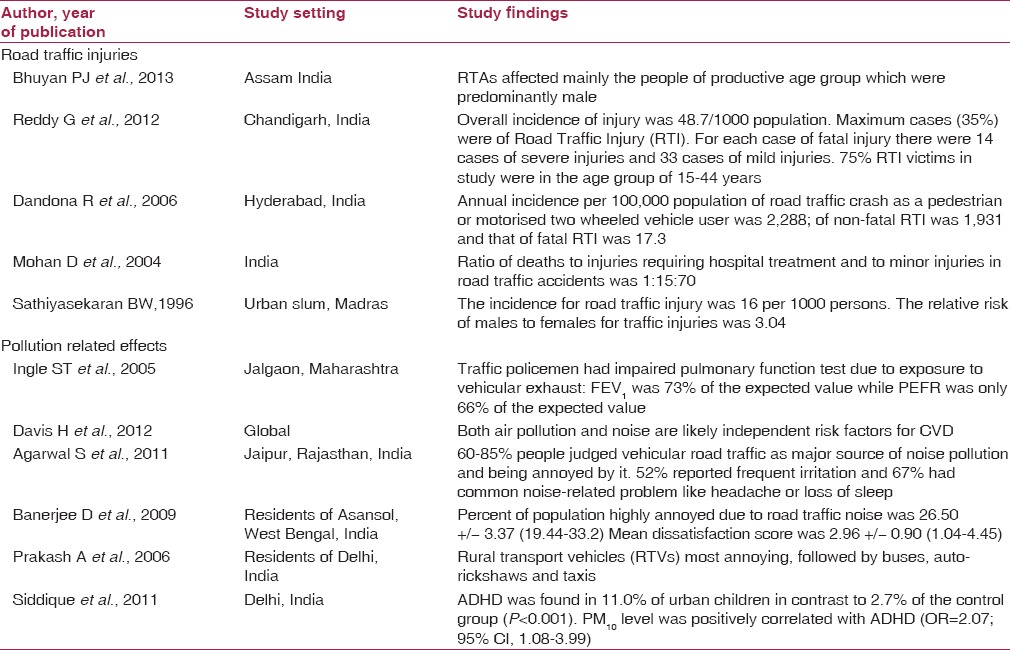

Air pollution due to vehicular traffic in urban dwellings can sensitize residents to pollens and is also associated with eczema in children.(31) Self-reported nasal discharge, blocked nose, sneezing and itching were strongly associated with living close to heavy traffic or living in cities. Proximity of residence of women during pregnancy to main road also increased the association of diagnosis of asthma and atopic eczema in the infants born to these women.(32) Some of the studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indian studies showing effects of urban transportation on health

Action

Tackling these problems require multifaceted actions, targeting various points in D-P-S-E-E-A framework. It would obviously be impossible to reduce all environmental exposures to a level at which the risk to human health is zero. Measures which address the higher end of the framework that is driving force, pressure and state of the environment are the most effective; but they are the ones which are most difficult to achieve.

There are numerous examples of interventions the world over which have been successful in reducing health effects, some of which are mentioned below.

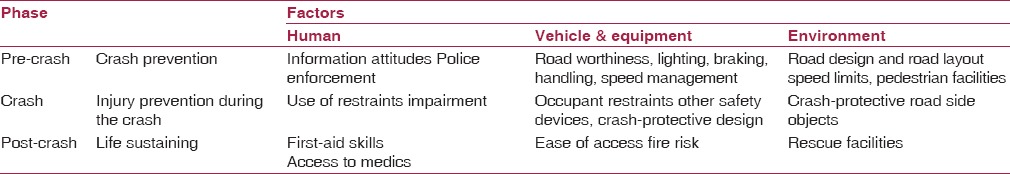

Traditionally, road safety has been assumed to be the responsibility of the transport sector. However road traffic injuries are a major public health issue, which needs to be tackled by the health department too. In USA about 30 years ago, William Haddon Jr described road transport as an ill designed “man-machine” system needing comprehensive systemic treatment. He produced what is now known as the Haddon Matrix, illustrating the interaction of three factors — human, vehicle and environment during three phases of a crash event: Pre-crash, crash and post-crash. The resulting nine-cell Haddon matrix models the dynamic system, with each cell of the matrix allowing opportunities for intervention to reduce road crash injury [Table 2].(38) This work led to substantial advances in the understanding of the behavioural, road-related and vehicle-related factors that affect the number and severity of causalities in road traffic accidents. Evidence from some highly-motorized countries shows that this integrated approach to road safety produces a marked decline in road deaths and serious injuries.(39) Studies in Denmark have shown that providing segregated bicycle tracks or lanes alongside urban roads reduced deaths among cyclists by 35%.(40) In Ghana, the use of rumble strips reduced crashes by 35% and deaths by 55% in certain locations.(41) In Ahmedabad, Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) was started since 2009, and now carries about 400,000 passengers a day. Since then, transport has shifted away from private vehicles to the BRT system, and there has been more than 50% decrease in road traffic fatalities in the BRT corridor.(42)

Table 2.

The Haddon Matrix

Research is also necessary to discover new technologies and opportunities for road safety from time to time. The Transportation Research and Injury Prevention Programme at the Institute of Technology in New Delhi, India is one such institute.

Besides road traffic accidents, other health benefits have been reported by efforts to reduce pollution due to road transport. Recent research in Canada indicated that adults who moved away from residences in close proximity to traffic (<150 m from a highway or <50 m from a major road) had a lower risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality than did those remaining in locations close to traffic.(43) Additionally, children who moved away from residences with high background PM10 experienced an increased rate of lung function growth compared with children who moved to areas with high PM10.(44) In London, positive health impacts have resulted from the implementation of the congestion charge scheme, which included an increase in active transport (cycling and walking), a decrease in noise pollution and related stress.(45)

Steps underway in Indian cities

The Government has taken steps in Indian cities for providing cleaner, more efficient and alternate mode of transportation. Metro Rail Projects were started in India beginning with commissioning of first phase of Delhi Metro in 2004. Presently Metro trains are running in Delhi, Haryana (Gurgaon), Uttar Pradesh (NOIDA, Ghaziabad), Karnataka (Bangalore) and Mumbai (Maharashtra). Approval for new metro network development has been granted in Kolkata, Chennai and Hyderabad. Moreover, Delhi has adopted Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) for public transportation.

In 2006, National Urban Transport Policy was approved to ensure safe, affordable, quick, comfortable, reliable and sustainable transportation systems in the cities for mobility needs of the residents. It emphasises on incorporation of urban transport at the urban planning stage with focus on more equitable road space allocation. Unified Metropolitan Transport Authorities in all million plus cities has been recommended. Under Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, 63 cities were identified to provide cash assistance in grants by Central Government for infrastructure developments projects including urban transportation sector as roads, highways, expressways, Mass Rapid Transport System and metro projects. Bus based public transport systems are to be incentivised under this scheme. It is estimated that an investment of Rs 4,35,380 crores is required between 2008 and 2027 to improve urban transportation in 87 identified cities.(46) The National Safety Council of India launched a campaign “The National Safety Day/Safety Week Campaign” for nearly three decades to mark its Foundation Day (4th March). These activities have significantly contributed to reduction in the rate of accidents and created wide spread safety awareness. Road Safety Week is observed every year from 1st–7th January.

In recognition that road accidents are a major public health problem. National Road Safety Policy was approved in India in 2010 based on Sunder committee recommendations. Under this policy Government of India has committed to increase awareness about road safety issues, establish a road safety information database, ensure safer road infrastructure, vehicles, drivers and safety of vulnerable road users.

Recommendations

There is sufficient evidence to show that effective measures can reduce morbidity and mortality due to road transport, which could take the form of a policy or comprehensive plan of action. Exposure to air pollutants is largely beyond the control of individuals, and requires action by public authorities at all levels. Enforcement of speed and alcohol limits, child restraints, safety belts and helmet use; pedestrian friendly front ends of vehicles and collision warning systems and design changes in vehicles like low floor buses with automatic closing doors, better and functional headlights and reflectors etc. to increase visibility of vehicles will help prevent or decrease accidents and injuries. Measures like regulating vehicle entry to city centers at busy hours, hike in parking charges and taxes will decrease congestion, commuting time, stress, risk of accidents and pollution. On the other hand, health services should be strengthened especially access to emergency trauma services, enhance capacity at all levels from primary to tertiary level of care in health promotion and patient management; this would go a long way in reducing morbidity and mortality due to health effects either from accidents or other pollution related ill-health effects.

Conclusion

This paper highlights some of the adverse health impacts of urban transportation in India where planning and management of transportation activities has not kept pace with increasing demands due to rapid urbanization. A combination of approaches will be required to address the problems in all levels according to D-P-S-E-E-A framework. The role of the government is crucial in planning and strict implementation of safety measures; there is therefore urgent need for capacity building and research, strengthening and enabling legal, institutional, and financial environment for road safety. Health system strengthening should be given priority to achieve significant reduction of health effects of road transport. Although policies, rules and intent are in place, results will only be visible if implementation, enforcement and monitoring are done effectively.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Office of Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 15]. Available from: http://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/paper2/data_files/india/Rural_Urban_2011.pdf .

- 2.Ch 4. New Delhi: Ministry of Road Transport and Highways Government of India; 2012. Road transport. Transport Research Wing, Annual report 2011-12; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Framework for linkages. Framework for linkages between health, environment and development. World Health Organization. 2002. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 30]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/events/IndicatorsChapter7.pdf .

- 4.Bandyopadhyay KR. Centre for Research on Energy Security. Vol. 5. The Energy and Resources Institute; 2010. Potential and challenges of electricity-driven vehicles in India.Energy security insights; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.New Delhi: 2012. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 11]. Road accidents in India Issues and dimensions. Transport research wing, Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. Government of India. Available from: http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/2.12.India_.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dandona R, Kumar GA, Raj TS, Dandona L. Patterns of road traffic injuries in a vulnerable population in Hyderabad, India. Inj Prev. 2006;12:183–8. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.010728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohan D. Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. Delhi: Indian Institute of Technology; 2004. The road ahead: Traffic injuries and fatalities in India, Delhi: Transportation Research and Injury Prevention Programme 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhuyan PJ, Ahmed F. Road traffic accident: An emerging public health problem in Assam. Indian J Community Med. 2013;38:100–4. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.112441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.New Delhi: 2012. [Lastaccessed on 2013 Oct 15]. Accidental Deaths in India. In: Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India 2012. National Crime Record Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Available from: http://ncrb.gov.in/CD-ADSI-2012/accidental-deaths-11.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padam S, Singh SK. Urbanization and Urban Transport in India: The sketch for a policy. 2001. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 8]. Available from: http://www.seas.harvard.edu/TransportAsia/workshop_papers/Padam-Singh.pdf .

- 11.Rahman MH, Arslan MI, Chen Y, Ali S, Parvin T, Wang LW, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts among rickshaw drivers in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76:533–8. doi: 10.1007/s00420-003-0431-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy JI, Bennett DH, Melly SJ, Spengler JD. Influence of traffic patterns on particulate matter and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon concentrations in Roxbury, Massachusetts. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2003;13:364–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geneva, Switzerland: [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 15]. Air quality and health. Media centre. World health organization. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs313/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revised national ambient air quality standards, notifications. Air pollution. Control of pollution, divisions. Home. Ministry of environment and forests, government of India. [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.envfor.nic.in/sites/default/files/notification/Recved%20national.pdf .

- 15.Air quality data. Data/statistics. Central pollution control board. Ministry of environment and forest. Government of India. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 15]. Available from: http://cpcb.nic.in/Data-2006_air.php .

- 16.Goyal SK, Ghatge SV, Nema P, M Tamhane S. Understanding urban vehicular pollution problem vis-a-vis ambient air quality--case study of a megacity (Delhi, India) Environ Monit Assess. 2006;119:557–69. doi: 10.1007/s10661-005-9043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbosa AS, Cardoso MR. Hearing loss among workers exposed to road traffic noise in the city of São Paulo in Brazil. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2005;32:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhosale BJ, Late A, Nalawade PM, Chavan SP, Mule MB. Studies on assessment of traffic noise level in Aurangabad city, India. Noise Health. 2010;12:195–8. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.64971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal S, Swami BL. Road traffic noise, annoyance and community health survey — A case study for an Indian city. Noise Health. 2011;13:272–6. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.82959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prakash A, Joute K, Jain VK. An estimation of annoyance due to various public modes of transport in Delhi. Noise Health. 2006;8:101–7. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.33950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ising H, Ising M. Chronic cortisol increases in the first half of the night caused by road traffic noise. Noise Health. 2002;4:13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leon Bluhm G, Berglind N, Nordling E, Rosenlund M. Road traffic noise and hypertension. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:122–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.025866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies H, Kamp IV. Noise and cardiovascular disease: A review of the literature 2008-2011. Noise Health. 2012;14:287–91. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.104895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sørensen M, Hvidberg M, Andersen ZJ, Nordsborg RB, Lillelund KG, Jakobsen J, et al. Road traffic noise and stroke: A prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:737–44. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sørensen M, Andersen ZJ, Nordsborg RB, Jensen SS, Lillelund KG, Beelen R, et al. Road traffic noise and incident myocardial infarction: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gómez-Jacinto L, Moral-Toranzo F. Urban traffic noise and self-reported health. Psychol Rep. 1999;84:1105–8. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.84.3c.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shepherd D, Welch D, Dirks KN, McBride D. Do quiet areas afford greater health-related quality of life than noisy areas? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:1284–303. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10041284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Noise pollution (Regulation and Control) Rules 2000. Noise standards, Central Pollution Control Board, Ministry of Environment and Forest. Government of India. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.cpcb.nic.in/divisionsofheadoffice/pci2/noise_rules_2000.pdf .

- 29.Banerjee D, Chakraborty SK, Bhattacharyya S, Gangopadhyay A. Evaluation and analysis of road traffic noise in asansol: An industrial town of eastern India. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2008;5:165–71. doi: 10.3390/ijerph5030165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bull F, Armstrong T, Dixon T, Ham S, Neiman A, Pratt M. Physical inactivity. In: Ezzati M, Lopez A, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, editors. Comparative quantification of health risks. Vol. 1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. pp. 729–882. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krämer U, Sugiri D, Ranft U, Krutmann J, von Berg A, Berdel D, et al. Eczema, respiratory allergies, and traffic-related air pollution in birth cohorts from small-town areas. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;56:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montnémery P, Popovic M, Andersson M, Greiff L, Nyberg P, Löfdahl CG, et al. Influence of heavy traffic, city dwelling and socio-economic status on nasal symptoms assessed in a postal population survey. Respir Med. 2003;97:970–7. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy G, Singh A, Singh D. Community based estimation of extent and determinants of cost of injuries in a north Indian city. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66:23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sathiyasekaran BW. Population-based cohort study of injuries. Injury. 1996;27:695–8. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(96)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ingle ST, Pachpande BG, Wagh ND, Patel VS, Attarde SB. Exposure to vehicular pollution and respiratory impairment of traffic policemen in Jalgaon City, India. Ind Health. 2005;43:656–62. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.43.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banerjee D, Chakraborty SK, Bhattacharyya S, Gangopadhyay A. Attitudinal response towards road traffic noise in the industrial town of Asansol, India. Environ Monit Assess. 2009;151:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s10661-008-0247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siddique S, Banerjee M, Ray MR, Lahiri T. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children chronically exposed to high level of vehicular pollution. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:923–9. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World report on road traffic injury prevention World Health Organization 2004. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 15]; Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/road_traffic/world_report/summary_en_rev.pdfsummary . [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lonero L. Road safety as a social construct. Ottawa, Northport Associates, 2002. Transport Canada Report No. 8080-00-1112 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrstedt L. Linköping: Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute; 1997. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 11]. Planning and safety of bicycles in urban areas. Proceedings of the traffic safety on two continents conference, Lisbon, 22-24 September 1997; pp. 43–58. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/road_traffic/world_report/summary_en_rev.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 41.Afukaar FK, Antwi P, Ofosu-Amah S. Pattern of road traffic injuries in Ghana: Implications for control. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2003;10:69–76. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.1.69.14107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Global status report on road safety: Supporting a decade of action. World Health Organization 2013. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2013/en/

- 43.Gan W, Tamburic L, Davies H, Demers P, Koehoorn M, Brauer M. Change in residential proximity to traffic and risk of death from coronary heart disease. Epidemiology. 2010;21:642–9. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89f19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Avol EL, Gauderman WJ, Tan SM, London SJ, Peters JM. Respiratory effects of relocating to areas of differing air pollution levels. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2067–72. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.11.2102005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tonne C, Beevers S, Armstrong B, Kelly F, Wilkinson P. Air pollution and mortality benefits of the London congestion charge: Spatial and socioeconomic inequalities. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65:620–7. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.036533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Study on traffic and transportation policies and strategies in urban areas in India. Wilbur Smith Associates PrivateLimited, Engineers and Planners; Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. 2008. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 11]. pp. 85–91. Available from: https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/sites/casi.sas.upenn.edu/files/iit/GOI%202008%20Traffic%20Study.pdf .