Abstract

Objective:

To identify the obstetric risk factors, incidence, and causes of uterine rupture, management modalities, and the associated maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality in one of the largest tertiary level women care hospital in Delhi.

Materials and Methods:

A 7-year retrospective analysis of 47 cases of uterine rupture was done. The charts of these patients were analyzed and the data regarding demographic characteristics, clinical presentation, risk factors, management, operative findings, maternal and fetal outcomes, and postoperative complications was studied.

Results:

The incidence of rupture was one in 1,633 deliveries (0.061%). The vast majority of patients had prior low transverse cesarean section (84.8%). The clinical presentation of the patients with rupture of the unscarred uterus was more dramatic with extensive tears compared to rupture with scarred uterus. The estimated blood loss ranged from 1,200 to 1,500 cc. Hemoperitoneum was identified in 95.7% of the patient and 83% of the patient underwent repair of rent with or without simultaneous tubal ligation. Subtotal hysterectomy was performed in five cases. There were no maternal deaths in our series. However, there were 32 cases of intrauterine fetal demise and five cases of stillbirths.

Conclusions:

Uterine rupture is a major contributor to maternal morbidity and neonatal mortality. Four major easily identifiable risk factors including history of prior cesarean section, grand multiparity, obstructed labor, and fetal malpresentations constitute 90% of cases of uterine rupture. Identification of these high risk women, prompt diagnosis, immediate transfer, and optimal management needs to be overemphasized to avoid adverse fetomaternal complications.

Keywords: Cesarean section, hysterectomy, obstructed labor, perinatal outcome, rupture of gravid uterus, uterine rupture

Introduction

Uterine rupture is an obstetrical emergency associated with severe maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. This catastrophic complication occurs most often in women attempting a vaginal birth after a prior cesarean delivery. In women who undergo a trial of labor after one prior low transverse cesarean section, the incidence of uterine rupture is estimated to be less than 1% and the rate of successful vaginal delivery varies from 60 to 80%.(1) Although most uterine ruptures occur in women with prior scarred uterus, rupture of the nulliparous unscarred uterus is also possible. Spontaneous uterine rupture is an extremely rare event, estimated to occur in one of 8,000 to one of 15,000 deliveries.(2)

Various factors reported in literature, which are associated with increased risk of uterine rupture include congenital uterine anomaly, grand multiparity, previous uterine surgery, fetal macrosomia, fetal malposition, labor induction, obstructed labor, uterine instrumentation, attempted forceps delivery, external version, and uterine trauma.(3,4,5)

Due to multiple reasons including, lack of health education, ignorance, or poverty; significant proportion of women in our country do not get regular antenatal checkup, preferring home delivery by traditional birth attendant instead of visiting the hospital. They visit the hospital in emergency situation after prolonged dysfunctional labor when traditional birth attendant fails to deliver the baby. The prolonged dysfunctional (obstructed) labor increases the risk of uterine rupture and rupture of previous cesarean scar.(6) Continuous rising trend of cesarean deliveries has increased the number of women exposed to the risk of a rupture uterus.

Due to potential grave consequences of uterine rupture to both mother and child, the obstetrician should have a high clinical suspicion for uterine rupture in the presence of abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, loss of fetal station, and non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns. Most commonly seen changes in the fetal heart rate pattern associated with uterine rupture are fetal bradycardia and late decelerations, occurring in up to 87.5% of cases.(3,7)

Fortunately, uterine rupture is a preventable condition. In order to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity in our community and meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 4 and 5, it is essential to determine the risk factors for ruptured uterus, which is a leading cause of maternal mortality in developing countries despite current knowledge.(8)

The aim of the present retrospective study is to identify the obstetric risk factors, incidence, and causes of uterine rupture and define the associated maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality in one of the largest tertiary level women care hospital in New Delhi.

Materials and Methods

Forty-seven patients over a period of 7 years were diagnosed with uterine rupture at Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kasturba Hospital, New Delhi, India and were included in the retrospective analysis. The study was approved by ethical committee of the institution. The charts of these patients were analyzed and the data regarding demographic characteristics, clinical presentation, risk factors, management, operative findings, maternal and fetal outcomes, and postoperative complications was studied. All cases included within the study had a full thickness uterine wall rupture, with acute maternal bleeding necessitating operative intervention. Asymptomatic uterine dehiscence, cases not requiring clinical or surgical intervention were excluded from the present study.

Results

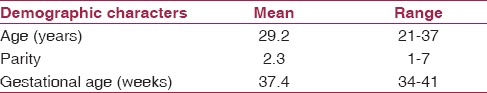

During the study period, 47 cases of uterine rupture were diagnosed out of total 76,766 deliveries. Thirty-six patients (76.6%) were unbooked in our hospital and 11 (23.4%) were booked cases. Maternal demographic characters are reported in Table 1. The mean (range) age of the patients diagnosed with uterine rupture was 29.2 (21-37) years. The mean (range) parity was 2.3 (1-7). The mean (range) gestational age was 37.4 (34-41) weeks.

Table 1.

Maternal demographic characters

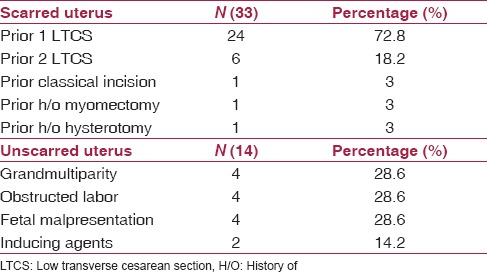

The incidence of rupture was calculated to be one in 1,633 deliveries (0.061%). The incidence of rupture was 0.318% in women with history of prior uterine surgery and was 0.02% in women without history of any prior uterine surgery. Among the cases with history of prior uterine surgery, the vast majority of patients had prior low transverse cesarean section (84.8%). There was only one patient with prior hysterotomy. The details of the risk factors associated with uterine rupture are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk factors associated with uterine rupture

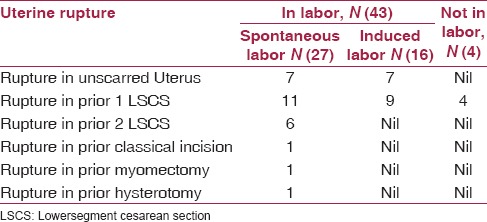

Most of the patients were in labor at the time of rupture. Only four patients with prior one lower segment cesarean section were not in labor at the time of rupture. Among the cases which ruptured in labor, a total of 16 patients were induced. All the inductions were performed in the labor room of the hospital conducting the study. The patients with prior two lower segment cesarean section, presented to our hospital in spontaneous labor and they were diagnosed with rupture uterus in our hospital. The distribution of the case ruptured while in labor or not in labor is described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of case ruptured while in labor or not in labor

Lower segment scar rupture was found in 44.6% cases followed by scar rupture extending to right and left lateral walls (29.78%) and lower segment extending to upper segment (17.02%). Only four (8.5%) cases were upper segment rupture. Rupture extended to the bladder in two cases, to broad ligament in four cases, and involved vaginal vault and cervix in five cases.

The clinical presentation of the patients with rupture of the unscarred uterus was more dramatic with extensive tears, hypotension, and shock. Rupture of scarred uterus, on the other hand, was usually incomplete and transverse. Signs of shock were rarely a presenting feature in this group.

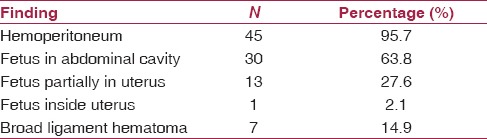

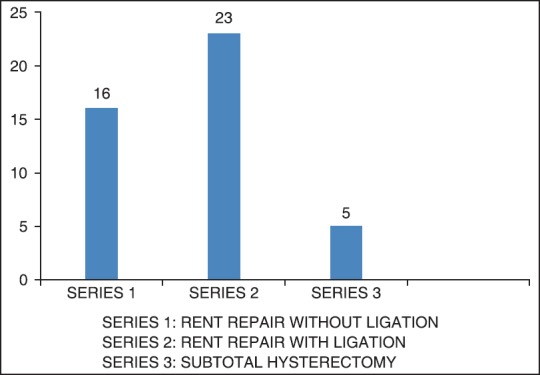

Intraoperatively, the estimated blood loss ranged from 1,200 to 1,500 cc. Hemoperitoneum was identified in 95.7% of the patients. Thirty-two patients received blood transfusion either intraoperatively or postoperatively. Other intraoperative findings are described in Table 4. The choice of surgical procedure was based upon the type, location, and extent of tear; patient's hemodynamic status; and desire for future fertility. Eighty-three percent of the patient underwent repair of rent with or without simultaneous tubal ligation. Rent repair required less operative time and was considered a better option for hemodynamically unstable patients. Subtotal hysterectomy was performed in five cases, where repair was not possible [Figure 1].

Table 4.

Intraoperative findings

Figure 1.

Management of patients with rupture uterus

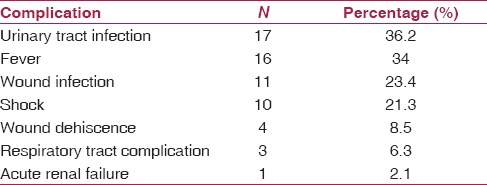

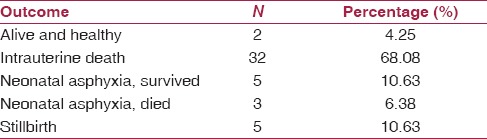

Postoperatively, the most common complication was urinary tract infection seen in 36.2% of patients. Second most common complication was febrile morbidity seen in 34% of patients. 21.3% of patient developed shock. Other less common complications are described in Table 5. Despite the presence of grave maternal complications, no maternal death occured in our series. However, the fetal outcome was poor as described in Table 6. There were 32 cases of intrauterine fetal demise and five cases of stillbirths. Eight babies had low Apgar scores and three of them died in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Table 5.

Postoperative complications

Table 6.

Fetal outcome

Discussion

Rupture of the gravid uterus is an unexpected, rare, and potentially life-threatening devastating complication. It still constitutes one of the most serious obstetrical emergencies.(9) Despite the advances of modern medicine, it continues to cause adverse fetal and maternal health consequences.

The incidence of one in 1,633 deliveries (0.061%) for uterine rupture in our series is similar to that reported in previous publications.(10,11) Our population-based study not only confirmed several important independent risk factors for uterine rupture, including previous cesarean section, multiparity, malpresentations, and labor dystocia; but also demonstrated that four major risk factors (history of prior uterine surgery, grand multiparity, obstructed labor, and fetal malpresentations) contributed to more than 90% cases of uterine rupture. The single risk factor (history of prior cesarean section) contributed to 66% cases of uterine rupture. Therefore, a great degree of caution should be taken while managing patients with previous uterine scar who are attempting trial of labor. Repeat cesarean delivery should be strongly considered in women with previous scarred uterus, if their Friedman's labor curve deviates from normal. Hamilton et al., reported that with labor dystocia (i. e., cervical dilatation lower than the 10th percentile and arrest for more than 2 h), cesarean delivery prevents more than 42.1% cases of uterine rupture.(12)

The most common predisposing factors for rupture uterus reported in literature are grand multiparity, obstetrical trauma, fetal macrosomia, and malpresentations.(3,4,5) However, in our patient population, the most common risk factor was prior cesarean delivery. Thus, with the continued rising trend of cesarean section, the number of women presenting to the labor ward with a scarred uterus is increasing, thereby exposing them to an increased risk for maternal morbidity, including uterine rupture.(13)

The risk of uterine rupture differs significantly depending on the type of the prior incision (low transverse, low vertical, classical, or unknown). A prospective observational study of 45,988 women with a singleton gestation estimates uterine rupture rates of 0.7% for low transverse incisions, 2.0% for low vertical incisions, and 0.5% for unknown scars.(14) A clinical challenge is presented in the patients with an unknown prior scar. Given the circumstances surrounding the delivery, obstetricians should infer which type of uterine incision is most likely in this group of patients. The risk of rupture with a T-shaped or classical incision is much higher, and ranges from 4 to 9%.(15)

The consequences of this potentially life-threatening condition depend on the time that has elapsed from the occurrence of rupture until the definitive management. Prompt maternal supportive and resuscitative measures should be undertaken to avoid catastrophic consequences like life-threatening uterine hemorrhage and maternal shock.

Once the rupture uterus is diagnosed, prompt management is the essence. Patient, if in clinical shock needs immediate resuscitation and surgical intervention. After the situation is fully evaluated, obstetrician then needs to decide if the rupture is surgically reparable or hysterectomy is needed. The choice of the surgical procedure also depends upon the type, location, and the extent of the uterine tear. Several authors considered subtotal or total hysterectomy as procedure of choice; whereas, others recommend that surgical repair is a safer immediate treatment.(16,17) In our study, successful repair were achieved in 83% of cases. However, repair of ruptured uterus increases the possibility of recurrence of rupture in subsequent pregnancies, with reported incidence of 4.3-19%.(18,19) Therefore, elective repeat cesarean delivery should be performed in this group of patients. Extensive counseling regarding future pregnancy and potentially associated complications should always be done with the patient.

Controversy exists in the literature regarding maternal mortality. Our study and many other studies did not find any maternal death after a uterine rupture.(3) However there are other studies reporting maternal mortality rates ranging from 0 to 13%.(20,21) Absence of maternal mortality in our patient population demonstrates that with prompt diagnosis and optimal management of the patients with the high risk factors, the maternal mortality can be reduced to zero.

Definitive therapy for the fetus is delivery via emergent surgical intervention, which is helpful in avoiding or reducing major fetal morbidities including fetal hypoxia, anoxia, acidosis, and fetal mortality. Delivery within 30 min after the uterine rupture is suspected clinically is associated with good long-term neonatal outcomes.(22) However, majority of our patients were unbooked and were transferred to the hospital in emergency after obstructed labor or uterine rupture was suspected. The time delay between onset of rupture and delivery contributed to high neonatal mortality, as demonstrated in our study. Adequate transportation facilities should be available with primary care centers so that these patients can be transferred to higher centers immediately. Additionally, lack of level 1 nursery at our institution contributed to higher neonatal morbidity and mortality. Therefore, we emphasize the importance of early identification of at-risk women for uterine rupture and early referral to a tertiary care center.

Early identification of nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns can help the obstetrician to suspect uterine rupture early. However, there is lack of availability of electronic fetal monitors in our institution and majority of the institutions in our country. We presume that once continuous electronic fetal monitoring facilities are more readily available, incidence of grave maternal and neonatal consequences can be reduced.

Our study was limited due to its retrospective nature. We were only able to review the information that was adequately documented in patient records. We could not evaluate the time lost in transportation of the patient to our hospital after the uterine rupture was clinically suspected at outside facility and effect of this time delay on the neonatal outcome.

In conclusion, uterine rupture is a major contributor to maternal morbidity and neonatal mortality. Four major easily identifiable risk factors including history of prior cesarean section, grand multiparity, obstructed labor, and fetal malpresentations account for 90% cases of uterine rupture. Identification of these high risk women, prompt diagnosis, immediate transfer, and optimal management needs to be overemphasized to avoid adverse fetomaternal complications. Extreme caution should be taken when managing patient with a previous uterine scar, attempting a trial of labor. Increased accessibility to good obstetric care and prompt referral system to equipped facilities with availability of transportation services is essential for developing countries to avoid these catastrophic emergencies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Smith JG, Mertz HL, Merrill DC. Identifying risk factors for uterine rupture. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:85–99. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller DA, Goodwin TM, Gherman RB, Paul RH. Intrapartum rupture of the unscarred uterus. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:671–3. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmer RM, Kirschbaum T, Potter D, Strong TH, Medearis AL. Uterine rupture during trial of labor after previous cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:996–1001. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller DA, Diaz FG, Paul RH. Vaginal birth after cesarean: A 10-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:255–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nkemayim DC, Hammadeh ME, Hippach M, Mink D, Schmidt W. Uterine rupture in pregnancy subsequent to previous laparoscopic electromyolysis. Case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2000;264:154–6. doi: 10.1007/s004040000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahbuba D, Alam IP. Uterine rupture — Experience of 30 cases at Faridpur medical college hospital. Faridpur Med Coll J. 2012;7:79–81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung AS, Leung EK, Paul RH. Uterine rupture after previous cesarean delivery: Maternal and fetal consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:945–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90032-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omole-Ohonsi A, Attah R. Risk factors for ruptured uterus in a developing country. Gynecol Obstet. 2011;1:102. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eden RD, Parker RT, Gall SA. Rupture of the pregnant uterus: A 53-year review. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:671–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardeil F, Daly S, Turner MJ. Uterine rupture in pregnancy reviewed. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;56:107–10. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waterstone M, Bewley S, Wolfe C. Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: Case-control study. BMJ. 2001;322:1089–93. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton EF, Bujold E, McNamara H, Gauthier R, Platt RW. Dystocia among women with symptomatic uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:620–4. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.110293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chazotte C, Cohen WR. Catastrophic complications of previous cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:738–42. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Leindecker S, Varner MW, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2581–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice bulletin no.115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:450–63. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garnet JD. Uterine rupture during pregnancy. An analysis of 133 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1964;23:898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weingold AB, Sall S, Sherman DH, Brenner PH. Rupture of the gravid uterus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1966;122:1233–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheth SS. Results of treatment of rupture of the uterus by suturing. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1968;75:55–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1968.tb00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agüero O, Kizer S. Obstetric prognosis of the repair of uterine rupture. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1968;127:528–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aboyeji AP, Ijaiya MD, Yahaya UR. Ruptured uterus: A study of 100 consecutive cases in Ilorin, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2001;27:341–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2001.tb01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van der Merwe JV, Ombelet WU. Rupture of the uterus: A changing picture. Arch Gynecol. 1987;240:159–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00207711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmgren C, Scott JR, Porter TF, Esplin MS, Bardsley T. Uterine rupture with attempted vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: Decision-to-delivery time and neonatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:725–31. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318249a1d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]