Abstract

The use of laparoscopy has revolutionised the surgical field with its advantages of reduced morbidity with early recovery. Laparoscopic procedures have been traditionally performed under general anaesthesia (GA) due to the respiratory changes caused by pneumoperitoneum, which is an integral part of laparoscopy. The precise control of ventilation under controlled conditions in GA has proven it to be ideal for such procedures. However, recently the use of regional anaesthesia (RA) has emerged as an alternative choice for laparoscopy. Various reports in the literature suggest the safety of the use of spinal, epidural and combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia in laparoscopic procedures. The advantages of RA can include: Prevention of airway manipulation, an awake and spontaneously breathing patient intraoperatively, minimal nausea and vomiting, effective post-operative analgesia, and early ambulation and recovery. However, RA may be associated with a few side effects such as the requirement of a higher sensory level, more severe hypotension, shoulder discomfort due to diaphragmatic irritation, and respiratory embarrassment caused by pneumoperitoneum. Further studies may be required to establish the advantage of RA over GA for its eventual global use in different patient populations.

Keywords: General anaesthesia (GA), laparoscopy, pneumoperitoneum, spinal anaesthesia

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of laparoscopy in the field of surgery in the mid-1950s revolutionised surgical techniques due to reduction in overall medical costs, reduced bleeding, less post-operative surgical and pulmonary complications, and early recovery. The gradual shift of laparoscopy to include more complicated surgical procedures resulted in modifications of existing anaesthetic techniques. The various effects of induction of pneumoperitoneum, an integral part of laparoscopy, can result in respiratory embarrassment and cardiovascular changes best managed by the use of general anaesthesia (GA).[1] Since the initiation of the application of laparoscopy in various day-care surgeries, a more favourable anaesthetic technique is required allowing early recovery and ambulation. The evolution of anaesthetic medicine on scientifically and clinically relevant scales has propelled innovations and initiatives for newer yet safer techniques.[2] Advancements in anaesthesiology have been made on many fronts besides clinically relevant scales.[3,4,5]

On the contrary, advancements in anaesthetic techniques and drugs in the modern era have given birth and growth to newer controversies in the light of newer scientific evidences. Traditionally, GA was considered the sole technique, and various myths and facts discouraged the use of regional anaesthesia (RA). Among these, respiratory embarrassment and cardiovascular changes were the major aspects of concern which are considered to be best managed by the use of GA. Moreover, anaesthesiologists are more comfortable with the administration of GA in laparoscopic surgeries, and there is a general reluctance to take initiative for advancements in swapping anaesthetic techniques.

Recently, RA has been documented to be equally favourable in laparoscopic surgeries.[6] This review has been done to compare the merits and demerits of the use of RA vs GA in laparoscopic surgery.

METHODS OF LITERATURE SEARCH

A systematic literature search was made using search engines including PubMed, Google and Google Scholar with the use of the following single-text words and combinations: ‘Laparoscopic surgery’, ‘regional anaesthesia’, ‘general anaesthesia’ and ‘spinal anaesthesia’. The references of relevant articles were cross-checked, and the articles comparing RA with GA for laparoscopic surgery and the articles on the use of RA for laparoscopic surgeries were included.

SYSTEMIC EFFECTS OF PNEUMOPERITONEUM–NECESSARY CLINICAL SCENARIO

The creation of pneumoperitoneum is an integral part of any laparoscopic procedure and is usually done by insufflation of carbon dioxide for the proper visualisation of abdominal viscera and its manipulation. The main effects are due to raised intra-abdominal pressure leading to various respiratory, cardiovascular and neurologic alterations.

Cardiovascular

The cardiovascular effects are mainly dependent on the intra-abdominal pressure and the absorption of carbon dioxide into systemic circulation. At lower intra-abdominal pressures of less than 15 mmHg, the venous return is augmented due to the emptying of splanchnic vessels, and thus cardiac output and blood pressure are increased. At higher intra-abdominal pressures of more than 15 mmHg, due to compression of inferior vena cava and other collaterals, the venous return is decreased, thus reducing cardiac output and blood pressure.[7,8] Various bradyarrythmias leading to atrioventricular blocks and cardiac arrest have been documented due to vagal stimulation on the insertion of a trocar, peritoneal stretch or carbon dioxide embolization.[9]

Respiratory

These include reduced lung volumes, basal atelectasis, increased intrapulmonary shunting, raised peak and mean airway pressures, and are attributable to raised intra-abdominal pressures and cephalad migration of the diaphragm with reduced excursion. There may also be chances of endobronchial migration of the endotracheal tube, resulting in hypercarbia and hypoxia.[10]

Neurologic

Raised intracranial pressure with consequent reduced cerebral perfusion pressure may occur due to hypercapnia, raised intra-abdominal pressures, and head-down positioning. These changes can be detrimental in patients with reduced intracranial compliance.

Positioning

The most common laparoscopic procedures employ the Trendelenburg (head-up) or the reverse Trendelenburg (head-down) position, thus further potentiating the adverse effects of pneumoperitoneum. The venous return, cardiac output and mean arterial pressure are reduced further in the head-up position, with an increase in peripheral vascular and pulmonary resistance.[11] Respiratory system deterioration is considered to be maximally affected in the reverse Trendelenburg position but it also depends on the duration of pneumoperitoneum.[12]

CHOICE OF ANAESTHETIC TECHNIQUE FOR LAPAROSCOPY–THE BEST ONE

With the recent trend towards the use of laparoscopy in day-care surgeries, anaesthetic techniques have changed, with more emphasis on shorter and more favourable techniques. The ideal anaesthetic technique for laparoscopic surgery should maintain stable cardiovascular and respiratory functions, provide rapid post-operative recovery, lead to minimal post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and provide good post-operative pain relief for early mobility.

THE TRADITIONAL ANAESTHETIC TECHNIQUE — GA

The use of GA with controlled ventilation has been considered the most acceptable technique for laparoscopic procedures owing to the various effects of pneumoperitoneum. The use of rapidly-acting and shorter-duration intravenous agents such as propofol and etomidate as well as inhalational agents such as sevoflurane and desflurane has made GA a favourable technique for day-care laparoscopic procedures.[13,14] Use of the ultra-short-acting opioid analgesic remifentanil also favours GA in fast-track laparoscopic procedures.[15] The use of nitrous oxide in laparoscopic procedures has been controversial, but the recent literature does not convey any clinical advantage of avoiding it against a greater risk of intraoperative awareness.[16] The only advantage of avoiding nitrous oxide may be a lower incidence of PONV. The use of short-acting, non-depolarizing muscle relaxants has replaced depolarizing muscle relaxants such as succinylcholine from the balanced GA technique for laparoscopic surgeries, allowing for less post-operative muscle pain. Moreover, the increasing usage of newer drugs like alpha-2 agonists apart from traditionally used opioids is quite effective in the attenuation of stressor response during intubation.[17,18]

The use of Proseal laryngeal mask airway (LMA) with controlled ventilation can avoid endotracheal intubation in selected non-obese patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures, thus reducing the incidence of post-operative sore throat, but it should be limited to procedures with the use of low intra-abdominal pressures and mild tilt.[19,20]

The safest technique of anaesthesia remains GA with endotracheal intubation in those with no contraindications, with maintenance of intra-operative end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) around 35 mmHg with adjustments in tidal volume or respiratory rate.[21] The agents which directly depress the heart should be avoided, with the provision of anticholinergic drugs in case of sudden surge in vagal tone during laparoscopy.

EMERGENCE OF RA IN LAPAROSCOPIC SURGERY

The use of RA for laparoscopy had not gained popularity until recently due to the risk of aspiration and respiratory embarrassment caused by pneumoperitoneum, making it less favourable for a conscious patient. However, RA does provide numerous advantages over GA in terms of quicker recovery, effective post-operative pain relief, no airway manipulation, shorter post-operative stay, cost-effectiveness and reduced PONV.[22,23] Most of the uses of RA in the past have been limited to the patient population with significant co-morbidities, where it proved to be beneficial.[24,25] There is evidence that the use of RA in laparoscopy performed on awake patients may produce fewer changes in respiratory mechanics and arterial blood gases. The various regional techniques that can be safely used in laparoscopic procedures are as follows.

Epidural anaesthesia

It has emerged as a very safe technique for lower abdominal surgeries as well as for post-operative analgesia, with only occasional complications reported.[26] It has been used safely in laparoscopic procedures involving the upper abdomen, and has been shown to have no deleterious effects on respiratory mechanics. The effectiveness of the epidural technique is enhanced and a prolonged post-operative analgesic period is achieved with the use of adjuvant with local anaesthetics.[27,28,29] Epidural anaesthesia can be used in patients deemed unfit for GA with the provision of effective post-operative analgesia.[30]

Spinal anaesthesia

The spinal anaesthesia may be more feasible and can provide better laparoscopic surgical conditions due to profound muscle relaxation and shorter recovery. There has been several reports in the literature for the safe use of spinal anaesthesia for laparoscopic upper abdominal and lower abdominal procedures.[31,32,33] The main advantages of spinal anaesthesia are: An awake, spontaneously breathing patient; prevention of airway manipulation; less incidence of PONV; and the provision of effective post-operative analgesia with a shorter recovery time.[34]

There are a few concerns related to the use of spinal anaesthesia for laparoscopic procedures. The incidence of hypotension has been noted to be up to 20.5% and can be augmented by the Trendelenburg position and increased intra-abdominal pressures.[35] However, various studies show that it can be easily prevented by liberally preloading the patient, reducing the head tilt, reducing the intra-abdominal pressure and the liberal use of vasopressors.[36,37]

The incidence of referred shoulder-tip pain varies 25-43%; it may be distressing to the patient in the post-operative period.[38] The etiology is thought to be subdiaphragmatic irritation of the peritoneum by the carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum. This can be reduced by lowering of the intra-abdominal pressures to 8-10 mmHg, the instillation of local anaesthetics into the peritoneal cavity or the use of parenteral opioids.[39,40]

The changes in respiratory mechanics due to pneumoperitoneum may cause increase in PaCO2 due to absorption from peritoneum, resulting in ventilatory changes. However, various reports in the literature support non-significant changes in either PaO2 or PaCO2 during laparoscopic surgery under spinal anaesthesia.[41]

Combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia

The use of combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia offers many advantages over either of the techniques by ensuring rapid onset of anaesthesia compared to epidural alone and reduced intrathecal doses of local anaesthetics required compared to spinal anaesthesia. It also entails the provision of effective post-operative analgesia and early ambulation of patients. The incidence of side effects is low with slight alterations in the positioning of the patient and by restriction of intra-abdominal pressures.[42]

GA VS RA — CURRENT EVIDENCE

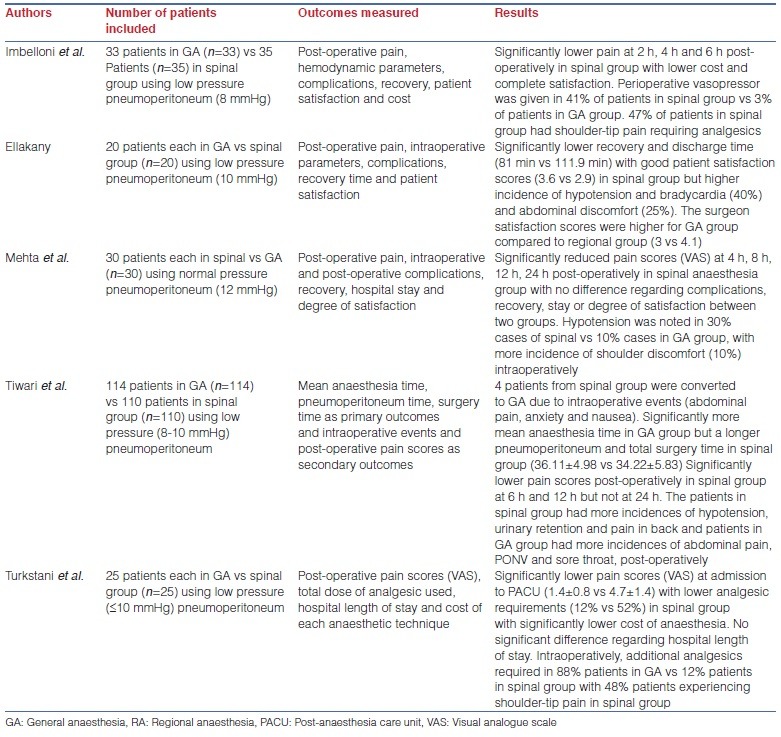

Evidence is lacking from developing nations regarding various advancements, mainly owing to the practice of scarce reporting of advancements and innovations. However, recently data reporting has witnessed a slight uptrend in the developing nations imbibing empiricism and scientific evidence.[43,44] RA provides various advantages over GA, such as reduction of surgical stress response, prevention of airway instrumentation, provision of effective post-operative analgesia, and early ambulation with lower incidence of deep vein thrombosis. There are numerous studies in the literature comparing GA and RA for laparoscopic surgery, which suggests that RA may be a good alternative. The main concerns associated with the use of RA are accelerated hypotension due to sympathetic blockade, ventilatory changes due to the higher sensory levels required, occurrence of shoulder-tip pain due to diaphragmatic irritation, and increased surgical time due to limitation of the intra-abdominal pressure.

Turkstani et al. compared GA with spinal anaesthesia in 50 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) and found significantly lower pain scores with lower analgesic consumption in the post-operative period in those with spinal anaesthesia. The total length of hospital stay was not significantly different but the total cost of anaesthesia was significantly less in the spinal anaesthesia group. Shoulder-tip pain was recorded in 48% of patients and the hypotension was also seen in 8 patients, but both of these complications were easily controlled.[45]

Imbelloni et al. in their comparison of 68 patients undergoing LC under general or spinal anaesthesia also found spinal anaesthesia to be a safe and cost-effective technique, with 47% incidence of shoulder-tip pain and 41% incidence of significant hypotension, both of which responded to pharmacological treatment with opioids and vasopressors, respectively.[46]

Ellakany, in his study of 40 patients receiving either general or segmental thoracic spinal anaesthesia, found comparable surgical conditions with superior post-operative analgesia and significantly better satisfaction scores among patients in the spinal anaesthesia group. He also found a 40% incidence of significant hypotension and about 25% incidence of abdominal discomfort, which were easily managed. He found no patients with nausea and vomiting in the spinal anaesthesia group.[47] However, the use of newer, long-acting anti-emetics like palonosetron reduces the incidence of PONV to a significant extent.[48]

Mehta et al., in their study of 60 patients, also found better post-operative analgesia with spinal anaesthesia in comparison to GA for LC. They found no significant difference between the groups regarding intraoperative complications, recovery, length of hospital stay and degree of satisfaction. There was no incidence of nausea and vomiting in the patients who received spinal anaesthesia.[49]

All the studies in the literature suggest that RA may be considered comparable to GA in laparoscopic procedures regarding surgical conditions, intra- and post-operative complications, and hospital length of stay, but may be superior to GA with respect to the PONV, post-operative analgesia and early recovery.

The salient features of various studies comparing GA with RA are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Showing studies comparing GA vs RA in laparoscopic cholecystectomy

CONCLUSION

Laparoscopic procedures have been traditionally performed under GA due to the concerns about pneumoperitoneum-related respiratory changes associated with it. However, recently the use of RA has been introduced for these laparoscopic procedures. The evidence suggests the safety of the use of spinal, epidural and combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia in laparoscopy with minimal side effects which can easily be managed with the available pharmacological drugs. RA may provide certain advantages over GA, such as lack of airway manipulation, maintenance of spontaneous respiration, effective post-operative analgesia, minimal nausea and vomiting, and early recovery and ambulation. However, the safety of RA in laparoscopic procedures among various types of patient populations still needs to be verified by further studies. Additionally, the technique of anaesthesia for laparoscopic procedures remains a debatable issue and most of the time it depends upon the experience and competency of the anaesthesiologist.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gerges FJ, Kanazi GE, Jabbour-Khouri SI. Anesthesia for laparoscopy: A review. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajwa SJ, Takrouri MS. Innovations, improvisations, challenges and constraints: The untold story of anesthesia in developing nations. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8:1–2. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.128890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajwa SJ, Kalra S. A deeper understanding of anesthesiology practice: The biopsychosocial perspective. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8:4–5. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.125893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajwa SJ, Jindal R. Quality control and assurance in anesthesia: A necessity of the modern times. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8:134–8. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.134480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajwa SJ, Kalra S. Qualitative research in anesthesiology: An essential practice and need of the hour. Saudi J Anaesth. 2013;7:477–8. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.121055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins LM, Vaghadia H. Regional anaesthesia for laparoscopy. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2001;19:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(05)70210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutt CN, Oniu T, Mehrabi A, Schemmer P, Kashfi A, Kraus T, et al. Circulatory and respiratory complications of carbon dioxide insufflation. Dig Surg. 2004;21:95–105. doi: 10.1159/000077038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuckerman RS, Heneghan S. The duration of hemodynamic depression during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1233–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sprung J, Abdelmalak B, Schoenwald PK. Recurrent complete heart block in a healthy patient during laparoscopic electrocauterization of the fallopian tube. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:1401–3. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199805000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rauh R, Hemmerling TM, Rist M, Jacobi KE. Influence of pneumoperitoneum and patient positioning on respiratory system compliance. J Clin Anesth. 2001;13:361–5. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(01)00286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirvonen EA, Poikolainen EO, Pääkkönen ME, Nuutinen LS. The adverse hemodynamic effects of anesthesia, head-up tilt, and carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:272–7. doi: 10.1007/s004640000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salihoglu Z, Demiroluk S, Cakmakkaya S, Gorgun E, Kose Y. Influence of the patient positioning on respiratory mechanics during pneumoperitoneum. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2002;16:521–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh Bajwa SJ, Bajwa SK, Kaur J. Comparison of two drug combinations in total intravenous anesthesia: Propofol-ketamine and propofol-fentanyl. Saudi J Anaesth. 2010;4:72–9. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.65132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilmore DW, Kehlet H. Management of patients in fast track surgery. BMJ. 2001;322:473–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H, Choi PT, McChesney J, Buckley N. Induction with sevoflurane-remifentanil is comparable to propofol-fentanyl-rocuronium in PONV after laparoscopic surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:660–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03018422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tramer M, Moore A, McQuay H. Omitting nitrous oxide in general anaesthesia: Meta-analysis of intraoperative awareness and postoperative emesis in randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:186–93. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajwa S, Kulshrestha A. Dexmedetomidine: An adjuvant making large inroads into clinical practice. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:475–83. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.122044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bajwa SJ, Kaur J, Singh A, Parmar S, Singh G, Kulshrestha A, et al. Attenuation of pressor response and dose sparing of opioids and anaesthetics with pre-operative dexmedetomidine. Indian J Anaesth. 2012;56:123–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.96303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maltby JR, Beriault MT, Watson NC, Liepert D, Fick GH. The LMA-ProSeal is an effective alternative to tracheal intubation for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Anaesth. 2002;49:857–62. doi: 10.1007/BF03017420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maltby JR, Beriault MT, Watson NC, Liepert DJ, Fick GH. LMAClassic and LMA-ProSeal are effective alternatives to endotracheal intubation for gynecologic laparoscopy. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50:71–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03020191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salihoglu Z, Demiroluk S, Dikmen Y. Respiratory mechanics in morbid obese patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension during pneumoperitoneum. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20:658–61. doi: 10.1017/s0265021503001066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazdisnian F, Palmieri A, Hakakha B, Hakakha M, Cambridge C, Lauria B. Office microlaparoscopy for female sterilization under local anesthesia. A cost and clinical analysis. J Reprod Med. 2002;47:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins LM, Vaghadia H. Regional anesthesia for laparoscopy. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2001;19:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(05)70210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gramatica L, Jr, Brasesco OE, Mercado Luna A, Martinessi V, Panebianco G, Labaque F, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed under regional anesthesia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:472–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamad MA, El-Khattary OA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anesthesia with nitrous oxide pneumoperitoneum: A feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1426–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jindal R, Bajwa SJ. Paresthesias at multiple levels: A rare neurological manifestation of epidural anesthesia. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012;28:136–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.92474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bajwa S, Arora V, Kaur J, Singh A, Parmar SS. Comparative evaluation of dexmedetomidine and fentanyl for epidural analgesia in lower limb orthopedic surgeries. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:365–70. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.87264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S, Bajwa SJ. Neuraxial opioids in geriatrics: A dose reduction study of local anesthetic with addition of sufentanil in lower limb surgery for elderly patients. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:142–9. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.82781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bajwa SJ, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Singh G, Arora V, Gupta S, et al. Dexmedetomidine and clonidine in epidural anaesthesia: A comparative evaluation. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:116–21. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.79883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bajwa SJ, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Singh A, Bakshi G, Singh K, et al. Admixture of clonidine and fentanyl to ropivacaine in epidural anesthesia for lower abdominal surgery. Anesth Essays Res. 2010;4:9–14. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.69299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaghadia H, Viskari D, Mitchell GW, Berrill A. Selective spinal anesthesia for outpatient laparoscopy. I: Characteristics of three hypobaric solutions. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48:256–60. doi: 10.1007/BF03019755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lennox PH, Vaghadia H, Henderson C, Martin L, Mitchell GW. Small-dose selective spinal anesthesia for short-duration outpatient laparoscopy: Recovery characteristics compared with desflurane anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:346–50. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200202000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart AV, Vaghadi H, Collins L, Mitchell GW. Small-dose selective spinal anaesthesia for short-duration outpatient gynaecological laparoscopy: Recovery characteristics compared with propofol anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:570–2. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiwari S, Chauhan A, Chaterjee P, Alam MT. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anaesthesia: A prospective, randomised study. J Minim Access Surg. 2013;9:65–71. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.110965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinha R, Gurwara AK, Gupta SC. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anaesthesia: A study of 3492 patients. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:323–7. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartman B, Junger A, Klasen J, Benson M, Jost A, Banzhaf A, et al. The incidence and risk factors for hypotension after spinal anesthesia induction: An analysis with automated data collection. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1521–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200206000-00027. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palachewa K, Chau-In W, Naewthong P, Uppan K, Kamhom R. Complications of spinal anaesthesia stinagarind hospital. Thai J Anaesth. 2001;27:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzovaras G, Fafoulakis F, Pratsas K, Georgopoulou S, Stamatiou G, Hatzitheofilou C. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anaesthesia: A pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:580–2. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imbelloni LE, Sant’anna R, Fornasari M, Fialho JC. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anesthesia: Comparative study between conventional dose and low-dose hyperbaric bupivacaine. Local Reg Anesth. 2011;4:41–6. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S19979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boddy AP, Mehta S, Rhodes M. The effect of intraperitoneal local anesthesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:682–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000226268.06279.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Zundert AA, Stultiens G, Jakimowicz JJ, van den Borne BE, van der Ham WG, Wildsmith JA. Segmental spinal anaesthesia for cholecystectomy in a patient with severe lung disease. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:464–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mane RS, Patil MC, Kedareshvara KS, Sanikop CS. Combined spinal epidural anesthesia for laparoscopic appendectomy in adults: A case series. Saudi J Anaesth. 2012;6:27–30. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.93051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh Bajwa SJ. Anesthesiology research and practice in developing nations: Economic and evidence-based patient-centered approach. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:295–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.117039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bajwa SJ, Kalra S. Logical empiricism in anesthesia: A step forward in modern day clinical practice. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:160–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turkstani A, Ibraheim O, Khairy G, Alseif A, Khalil N. Spinal versus general anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A cost effectiveness and side effects study. APICARE. 2009;13:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imbelloni LE, Fornasari M, Fialho JC, Sant’Anna R, Cordeiro JA. General anesthesia versus spinal anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2010;60:217–27. doi: 10.1016/S0034-7094(10)70030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellakany M. Comparative study between general and thoracic spinal anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Egyptian J Anaesth. 2013;29:375–81. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bajwa SS, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Sharma V, Singh A, Singh A, et al. Palonosetron: A novel approach to control postoperative nausea and vomiting in day care surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:19–24. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.76484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mehta PJ, Chavda HR, Wadhwana AP, Porecha MM. Comparative analysis of spinal versus general anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A controlled, prospective, randomized trial. Anesth Essays Res. 2010;4:91–5. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.73514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]