Abstract

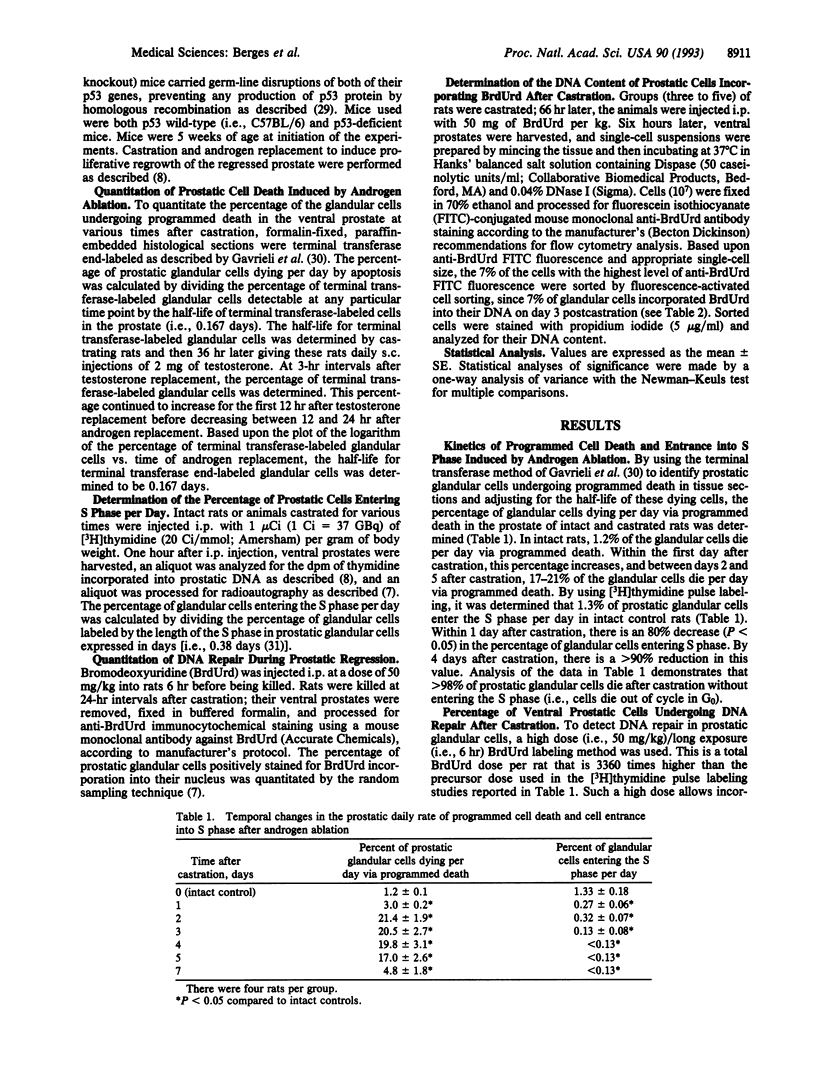

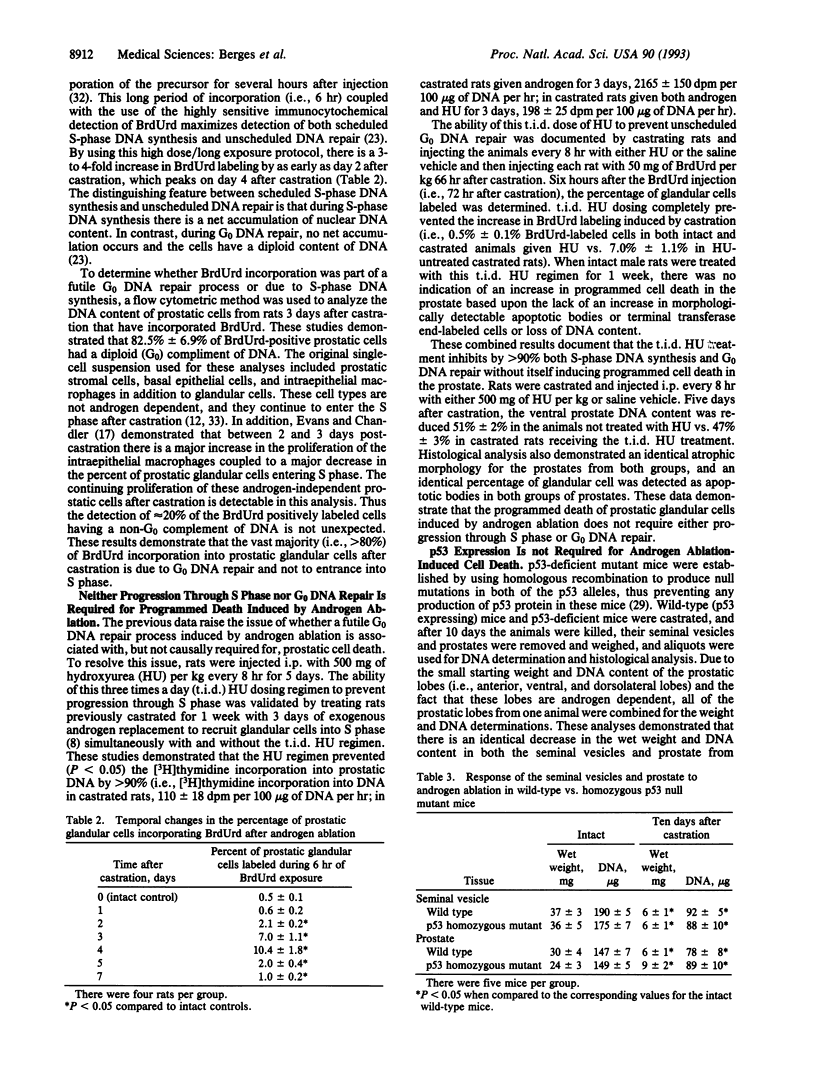

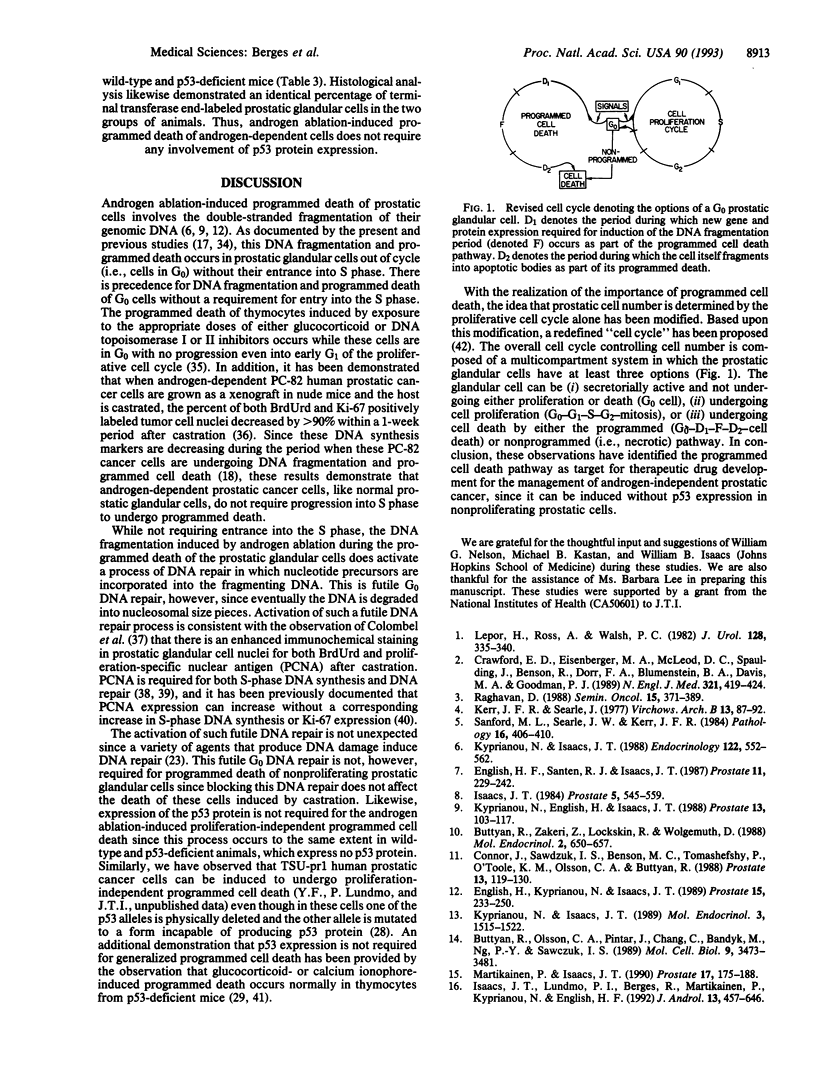

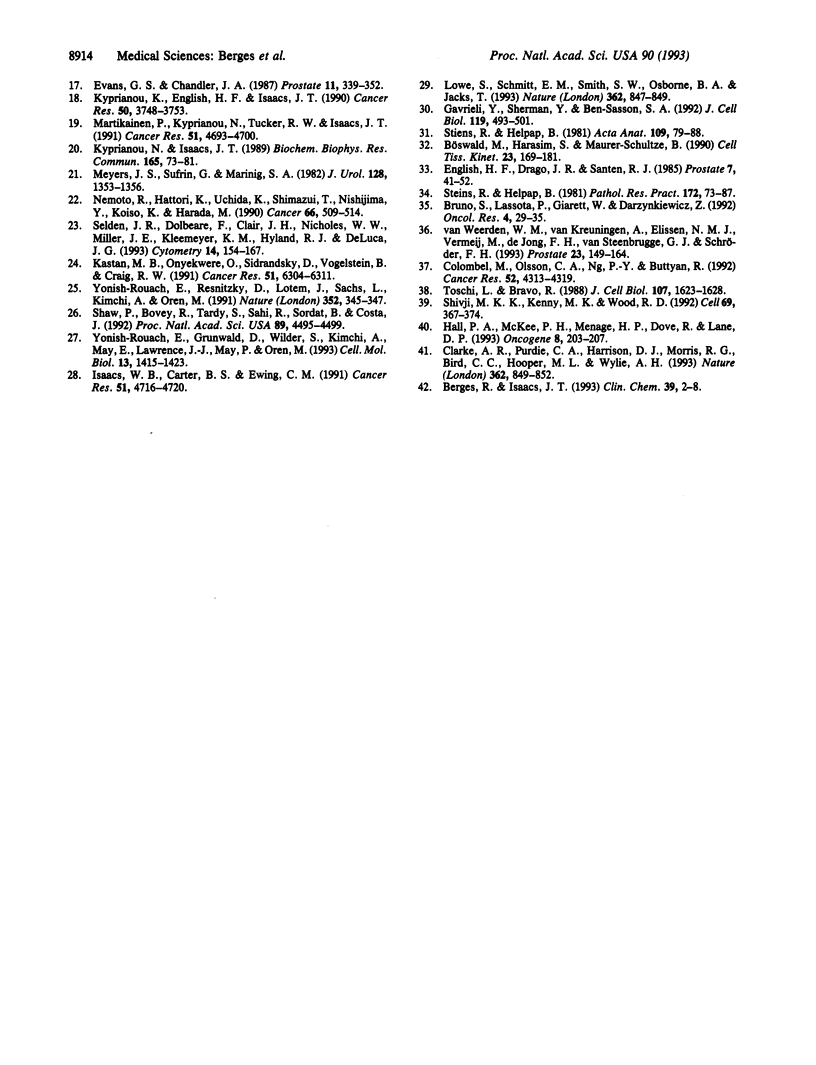

Androgen ablation induces programmed death of androgen-dependent prostatic glandular cells, resulting in fragmentation of their genomic DNA and the cells themselves into apoptotic bodies. Twenty percent of prostatic glandular cells undergo programmed death per day between day 2 and 5 after castration. During this same period, < 1% of prostatic glandular cells enter the S phase of the cell cycle, documenting that > 95% of these die in G0. During the programmed death of these G0 glandular cells, a futile DNA repair process is induced secondary to the DNA fragmentation. This futile DNA repair is not required, however, since inhibition of this process by > 90% with an appropriately timed hydroxy-urea dosing regimen had no effect upon the extent of the programmed death of these cells after castration. Likewise, p53 gene expression is not required since the same degree of cell death occurred in prostates and seminal vesicles after castration of wild-type and p53-deficient mice.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bruno S., Lassota P., Giaretti W., Darzynkiewicz Z. Apoptosis of rat thymocytes triggered by prednisolone, camptothecin, or teniposide is selective to G0 cells and is prevented by inhibitors of proteases. Oncol Res. 1992;4(1):29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttyan R., Olsson C. A., Pintar J., Chang C., Bandyk M., Ng P. Y., Sawczuk I. S. Induction of the TRPM-2 gene in cells undergoing programmed death. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Aug;9(8):3473–3481. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttyan R., Zakeri Z., Lockshin R., Wolgemuth D. Cascade induction of c-fos, c-myc, and heat shock 70K transcripts during regression of the rat ventral prostate gland. Mol Endocrinol. 1988 Jul;2(7):650–657. doi: 10.1210/mend-2-7-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böswald M., Harasim S., Maurer-Schultze B. Tracer dose and availability time of thymidine and bromodeoxyuridine: application of bromodeoxyuridine in cell kinetic studies. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1990 May;23(3):169–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1990.tb01113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A. R., Purdie C. A., Harrison D. J., Morris R. G., Bird C. C., Hooper M. L., Wyllie A. H. Thymocyte apoptosis induced by p53-dependent and independent pathways. Nature. 1993 Apr 29;362(6423):849–852. doi: 10.1038/362849a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombel M., Olsson C. A., Ng P. Y., Buttyan R. Hormone-regulated apoptosis results from reentry of differentiated prostate cells onto a defective cell cycle. Cancer Res. 1992 Aug 15;52(16):4313–4319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J., Sawczuk I. S., Benson M. C., Tomashefsky P., O'Toole K. M., Olsson C. A., Buttyan R. Calcium channel antagonists delay regression of androgen-dependent tissues and suppress gene activity associated with cell death. Prostate. 1988;13(2):119–130. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990130204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford E. D., Eisenberger M. A., McLeod D. G., Spaulding J. T., Benson R., Dorr F. A., Blumenstein B. A., Davis M. A., Goodman P. J. A controlled trial of leuprolide with and without flutamide in prostatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1989 Aug 17;321(7):419–424. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908173210702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English H. F., Drago J. R., Santen R. J. Cellular response to androgen depletion and repletion in the rat ventral prostate: autoradiography and morphometric analysis. Prostate. 1985;7(1):41–51. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990070106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English H. F., Kyprianou N., Isaacs J. T. Relationship between DNA fragmentation and apoptosis in the programmed cell death in the rat prostate following castration. Prostate. 1989;15(3):233–250. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990150304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English H. F., Santen R. J., Isaacs J. T. Response of glandular versus basal rat ventral prostatic epithelial cells to androgen withdrawal and replacement. Prostate. 1987;11(3):229–242. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans G. S., Chandler J. A. Cell proliferation studies in the rat prostate: II. The effects of castration and androgen-induced regeneration upon basal and secretory cell proliferation. Prostate. 1987;11(4):339–351. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990110406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrieli Y., Sherman Y., Ben-Sasson S. A. Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Cell Biol. 1992 Nov;119(3):493–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. A., McKee P. H., Menage H. D., Dover R., Lane D. P. High levels of p53 protein in UV-irradiated normal human skin. Oncogene. 1993 Jan;8(1):203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs J. T. Antagonistic effect of androgen on prostatic cell death. Prostate. 1984;5(5):545–557. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990050510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs J. T., Lundmo P. I., Berges R., Martikainen P., Kyprianou N., English H. F. Androgen regulation of programmed death of normal and malignant prostatic cells. J Androl. 1992 Nov-Dec;13(6):457–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs W. B., Carter B. S., Ewing C. M. Wild-type p53 suppresses growth of human prostate cancer cells containing mutant p53 alleles. Cancer Res. 1991 Sep 1;51(17):4716–4720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan M. B., Onyekwere O., Sidransky D., Vogelstein B., Craig R. W. Participation of p53 protein in the cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1991 Dec 1;51(23 Pt 1):6304–6311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J. F., Searle J. Deletion of cells by apoptosis during castration-induced involution of the rat prostate. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol. 1973 Jun 25;13(2):87–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02889300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyprianou N., English H. F., Isaacs J. T. Activation of a Ca2+-Mg2+-dependent endonuclease as an early event in castration-induced prostatic cell death. Prostate. 1988;13(2):103–117. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990130203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyprianou N., English H. F., Isaacs J. T. Programmed cell death during regression of PC-82 human prostate cancer following androgen ablation. Cancer Res. 1990 Jun 15;50(12):3748–3753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyprianou N., Isaacs J. T. "Thymineless" death in androgen-independent prostatic cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989 Nov 30;165(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyprianou N., Isaacs J. T. Activation of programmed cell death in the rat ventral prostate after castration. Endocrinology. 1988 Feb;122(2):552–562. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-2-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyprianou N., Isaacs J. T. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta in the rat ventral prostate during castration-induced programmed cell death. Mol Endocrinol. 1989 Oct;3(10):1515–1522. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-10-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepor H., Ross A., Walsh P. C. The influence of hormonal therapy on survival of men with advanced prostatic cancer. J Urol. 1982 Aug;128(2):335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52915-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe S. W., Schmitt E. M., Smith S. W., Osborne B. A., Jacks T. p53 is required for radiation-induced apoptosis in mouse thymocytes. Nature. 1993 Apr 29;362(6423):847–849. doi: 10.1038/362847a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen P., Isaacs J. Role of calcium in the programmed death of rat prostatic glandular cells. Prostate. 1990;17(3):175–187. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990170302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen P., Kyprianou N., Tucker R. W., Isaacs J. T. Programmed death of nonproliferating androgen-independent prostatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1991 Sep 1;51(17):4693–4700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. S., Sufrin G., Martin S. A. Proliferative activity of benign human prostate, prostatic adenocarcinoma and seminal vesicle evaluated by thymidine labeling. J Urol. 1982 Dec;128(6):1353–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)53506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto R., Hattori K., Uchida K., Shimazui T., Nishijima Y., Koiso K., Harada M. S-phase fraction of human prostate adenocarcinoma studied with in vivo bromodeoxyuridine labeling. Cancer. 1990 Aug 1;66(3):509–514. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3<509::aid-cncr2820660318>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan D. Non-hormone chemotherapy for prostate cancer: principles of treatment and application to the testing of new drugs. Semin Oncol. 1988 Aug;15(4):371–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandford N. L., Searle J. W., Kerr J. F. Successive waves of apoptosis in the rat prostate after repeated withdrawal of testosterone stimulation. Pathology. 1984 Oct;16(4):406–410. doi: 10.3109/00313028409084731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selden J. R., Dolbeare F., Clair J. H., Nichols W. W., Miller J. E., Kleemeyer K. M., Hyland R. J., DeLuca J. G. Statistical confirmation that immunofluorescent detection of DNA repair in human fibroblasts by measurement of bromodeoxyuridine incorporation is stoichiometric and sensitive. Cytometry. 1993;14(2):154–167. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990140207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P., Bovey R., Tardy S., Sahli R., Sordat B., Costa J. Induction of apoptosis by wild-type p53 in a human colon tumor-derived cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 May 15;89(10):4495–4499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivji K. K., Kenny M. K., Wood R. D. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen is required for DNA excision repair. Cell. 1992 Apr 17;69(2):367–374. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90416-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiens R., Helpap B. Die Regression der Rattenprostata nach Kastration. Histologische, morphometrische und zellkinetische Untersuchungen unter Berücksichtigung der Apoptose. Pathol Res Pract. 1981 Jul;172(1-2):73–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiens R., Helpap B. Histologische und proliferationskinetische Untersuchungen zum Wachstum der Rattenprostata in verschiedenen Lebensaltern. Acta Anat (Basel) 1981;109(1):79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toschi L., Bravo R. Changes in cyclin/proliferating cell nuclear antigen distribution during DNA repair synthesis. J Cell Biol. 1988 Nov;107(5):1623–1628. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonish-Rouach E., Grunwald D., Wilder S., Kimchi A., May E., Lawrence J. J., May P., Oren M. p53-mediated cell death: relationship to cell cycle control. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Mar;13(3):1415–1423. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonish-Rouach E., Resnitzky D., Lotem J., Sachs L., Kimchi A., Oren M. Wild-type p53 induces apoptosis of myeloid leukaemic cells that is inhibited by interleukin-6. Nature. 1991 Jul 25;352(6333):345–347. doi: 10.1038/352345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weerden W. M., van Kreuningen A., Elissen N. M., Vermeij M., de Jong F. H., van Steenbrugge G. J., Schröder F. H. Castration-induced changes in morphology, androgen levels, and proliferative activity of human prostate cancer tissue grown in athymic nude mice. Prostate. 1993;23(2):149–164. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990230208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]