By creating new incentives and accountability for providers, many believe that Accountable Care Organizations can help achieve the triple aim of better population health, better patient experience, and lower costs.1 Although private payers are supporting ACO formation, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ACO programs are the largest and most prominent. In fact, Medicare’s Shared Savings Program (MSSP) — the largest of the federal ACO models — has already grown to include 404 participants covering more than 7.3 million Medicare beneficiaries.2 To date, initial evaluations of the MSSP model have identified moderate success in reducing cost growth, while meeting quality and patient experience benchmarks.3,4 In order to achieve these goals, the earliest MSSP ACOs have focused on primary care, better care coordination, and reducing over-utilization of heath care services.5

What remains unclear, however, is the degree to which surgeons and other specialists are participating in MSSP programs, and whether such specialist integration influences ACO performance. Specialty care–particularly surgery–is a major driver of health care costs in the US, accounting for much of the observed spending differences with other countries.6 Nonetheless, specialists are not central to ACOs, and attribution of patients to ACOs is based exclusively on primary care services. Also, while a wide variety of providers can participate, specialists are not required for establishment of an MSSP ACO. In fact, the only statutory requirement is participation by enough providers to cover the plurality of primary care services for at least 5,000 fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries.7 Because cost savings with ACOs may require lower utilization of acute and specialty care services, surgeons and other specialists may also lack strong incentives to participate.

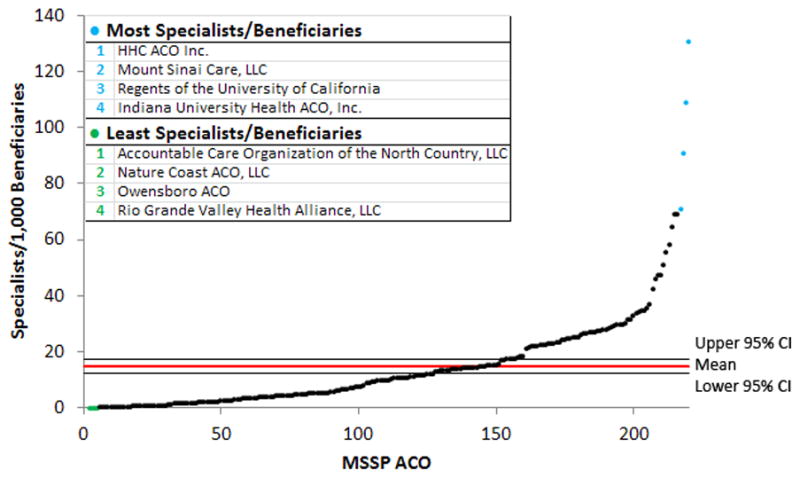

To explore the composition of physicians participation in MSSP ACOs, we used the recently released ACO Public Use File (PUF) that includes information on the number of specialists participating in each of the first 220 MSSP ACOs.8 Figure 1 presents the number of specialists per 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries across these organizations. The wide variation in specialist participation underscores the heterogeneous clinical structure of early ACOs. Namely, while some ACOs have formed around small, newly-created provider groups, others have formed around mature integrated delivery systems or multispecialty physician practices. For instance, included among the MSSP ACOs with the greatest number of specialists per beneficiaries are widely recognized academic medical centers and integrated delivery systems, including Mount Sinai, UCLA, Indiana University, and Billings Clinic.

Figure 1.

These data indicate that surgeons and other specialists are not well-represented in many early ACOs. This is consistent with other evidence: Dupree et al. found that 88% of CMS ACOs did not know how much their ACO was spending on surgical care. Moreover, only 11% of respondents thought their ACO provided perfectly or well-integrated care between surgeons and primary care physicians.5 Until and unless general surgeons and other surgical specialists become more integrated within the structure of ACOs, it may be difficult for these programs to achieve meaningful improvements in expensive procedural-based care.

For surgeons that are not already part of an integrated delivery system or multispecialty group that has initiated, or is considering, ACO participation, referral opportunities represent one potential incentive to join such programs. Hospital referral regions with ACOs tend to have more competition;9 as such, a desire to maintain or increase a referral base may motivate surgeon involvement.5 However, many argue that there are equally strong barriers to surgeon participation in ACOs. For individual surgeons, it is likely that any financial benefits from MSSP ACO participation will be relatively small in comparison to income received from current clinical volume. Accordingly, there may be limited enthusiasm among surgeons to participate in organizations that aim to reduce spending through lower utilization of surgical specialty services.5

In the absence of existing ties between surgical specialists and PCPs, one proposed model for better integrating clinical care in ACOs is the “medical neighborhood”. This model is based on explicit collaborative care agreements that outline expectations for interactions between providers10 in hopes of increasing efficiency at multiple stages of patient care. Benefits to specialists include coordinated workups and, potentially, a higher proportion of appropriate referrals.10 Still, it is unclear how willing both primary care providers and surgeons (or other specialists) would be to participate in these agreements, and how effectively they would integrate care.

Beyond these considerations, surgeons could seek to deepen their involvement and engagement with Medicare ACOs. This could include efforts to develop and validate of additional measures of surgical quality and value. By ensuring the availability of such metrics – applicable to a broad range of surgical subspecialties – surgeons will be poised to lead any efforts by CMS to more directly measure surgical quality in the MSSP and other ACO programs.

Another important - and related - step is to encourage broad representation of high quality surgical specialists in Medicare ACOs. This will ensure that beneficiaries have preserved access to the highest level of technical expertise for all surgical conditions. Moreover, participation by all surgical specialties may facilitate trans-disciplinary collaborative learning and sharing of best practices as surgeons in ACOs inevitably encounter both formal and informal pressures to emphasize “value over volume”, including new requirements to measure patient outcomes and the costs of surgical care episodes.

At present, participation by surgeons and other specialists in Medicare ACO programs is highly variable. Some ACOs include many specialists that are tightly integrated with PCPs, while others are comprised solely of primary care providers. Future research will evaluate the impact of surgeon participation in ACOs. These studies will help to determine whether ACOs are the right model to improve surgical quality and value, or whether other policies are needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (1-RO1-CA-174768 to DCM) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K01HS018546 to AMR). Scott Hawken and Dr. David Miller had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors thank Dr. Lindsey A. Herrel for her assistance in the analysis of the data and for revisions of the manuscript. Dr. Herrel was not compensated for her contributions.

Contributor Information

Scott R. Hawken, Email: hawken@med.umich.edu.

Andrew M. Ryan, Email: amryan@umich.edu.

References

- 1.McClellan M, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, Roski J, Fisher ES. A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):982–990. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed May 4, 2015];Fast Facts: All Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs. 2015 Apr; http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/All-Starts-MSSP-ACO.pdf.

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed October 20, 2014];Fact Sheets: Medicare ACOs Continue to Succeed in Improving Care, Lowering Cost Growth. 2014 Sep; http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2014-Fact-sheets-items/2014-09-16.html.

- 4.McWilliams JM, Landon BE, Chernew ME, Zaslavsky AM. Changes in Patients’ Experiences in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations. NEJM. 2014;371(18):1715–1724. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dupree JM, Patel K, Singer SJ, et al. Attention to surgeons and surgical care is largely missing from early medicare accountable care organizations. Health Aff. 2014;33:972–979. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laugesen MJ, Glied Sa. Higher fees paid to US physicians drive higher spending for physician services compared to other countries. Health Aff. 2011;30(9):1647–1656. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare& Medicaid Services. [Accessed October 20, 2014];Final Rule Provisions for Accountable Care Organziations under the Medicare Shared Savings Program. 2011 Nov; http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-11-02/pdf/2011-27461.pdf.

- 8.Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) PUF. [Accessed February 1, 2015];Centers Medicare Medicaid Serv. 2015 http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/SSPACO/Overview.html.

- 9.Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ, et al. Analysis of early accountable care organizations defines patient, structural, cost, and quality-of-care characteristics. Health Aff. 2014;33:95–102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg JO, Barnett ML, Spinks Ma, Dudley JC, Frolkis JP. The “medical neighborhood”: integrating primary and specialty care for ambulatory patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:454–457. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]