Abstract

Objective

The OMERACT RA Flare Group was established to develop an approach to identify and measure rheumatoid arthritis (RA) flares. Here, we provide an overview of our OMERACT 2014 plenary.

Methods

Feasibility and validity of flare domains endorsed at OMERACT 11 (2012) were described based on initial data from three international studies collected using a common set of questions specific to RA flare. Mean flare frequency, severity, and duration data were presented, and domain scores were compared by flare status to examine known-groups validity. Breakout groups provided input for stiffness, self-management, contextual factors, and measurement considerations.

Results

Flare data from 501 patients in a observational study indicated 39% were in a flare, with mean (SD) severity of 6.0 (2.6) and 55% lasting > 14 days. Pain, physical function, fatigue, participation and stiffness scores averaged ≥ 2 times higher (2 of 11 points) in flaring individuals. Correlations between flare domains and corresponding legacy instruments were r’s from 0.46 to 0.93. A combined definition (patient-report of flare and DAS28 increase) was evaluated in two other trials with similar results. Breakout groups debated specific measurement issues.

Conclusion

These data contribute initial evidence of feasibility and content validation of the OMERACT RA Flare Core Domain Set. Our research agenda for OMERACT 2016 includes establishing duration/intensity criteria and developing criteria to identify RA flares using existing disease activity measures. Ongoing work will also address discordance between patients and physician ratings, facilitate applications to clinical care, elucidate the role of self-management and help finalize recommendations for RA flare measurement.

Key indexing terms: flare, disease exacerbation, rheumatoid arthritis, OMERACT

There is a need to formalize methods to identify and characterize flares in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) across settings (1–5). Low disease activity and remission are the recommended targets of treatment (6, 7), and once achieved, it may be possible to taper therapies. However, a limitation of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and longitudinal observational studies (LOSs), especially those reporting on treatment tapering/withdrawal, has been the lack of a validated endpoint to identify the return of significant disease activity (i.e., flare) (8). The OMERACT RA Flare Group was established to address gaps in RA flare assessment. Since inception, an international steering committee of researchers and patient research partners have worked together to guide a larger group of RA researchers, clinicians, and patients with ongoing bidirectional input.

We defined clinically relevant inflammatory RA flares as reflecting a cluster of symptoms, signs, and impacts of sufficient intensity and duration to require consideration of (re)initiation, change, or increase in therapy (1, 2, 5). We began by conducting 14 focus groups across 5 countries with people with RA to identify experiences during a flare (9). A conceptual framework was developed to identify essential symptoms and impacts that represented disease flares, including their use of self-management strategies. Parallel and combined modified Delphi exercises were conducted with patients, health care providers (HCPs), and researchers to gain consensus on candidate domains for a prototype measurement model (10). Of note, researchers in additional settings independently identified similar flare domains (11, 12), patient assessments of RA disease activity, and preferred treatment outcomes (13, 14).

Results established a candidate RA Flare Core Domain Set that was endorsed by attendees at the OMERACT 11 meeting at Pinehurst, NC in 2012 (4). The RA Flare Core Domain Set included the ACR core set for RA (15), and added fatigue, stiffness, participation, and self-management. Our research agenda at OMERACT 11 was to: 1) identify existing instruments and/or develop new items if needed to assess each domain; and 2) gather preliminary evidence of content validation (16, 17). We developed a data collection tool to gather information about RA flare episodes at the time of clinical assessments in LOSs and RCTs. The questions to assess patient-reported flare and the OMERACT flare domains were rigorously translated (i.e., forward and back translation with adjudication and cognitive interviews)(18) from English into 13 languages, and consisted of three sections. Section 1 asked patients to rate changes in their RA since the last visit (7-point Likert scale: much worse to much better), and whether respondents believed they were currently experiencing a flare (Y/N); if yes, respondents were asked to rate the severity of flare (11-point numeric rating scale [NRS]) in the past week, its duration (days), and indicate use of self-management strategies (from a list provided). Section 2 asked for ratings of 6 domains (pain, physical function, fatigue, stiffness, participation, and coping) using an 11-point NRS. Section 3 asked respondents to indicate swollen and tender joints on a homunculus (counts of swollen joints and tender joints).

Here, we provide an overview of the results presented at an OMERACT 2014 plenary to validate flare domains, summarize breakout group discussions, identify remaining gaps, and provide an updated research agenda to finalize recommendations for flare assessment.

METHODS

Overview of Plenary Session

Prior to the plenary, a briefing session was held for patients to become familiar with our prior work and current goals to facilitate their participation during the conference. During the plenary, we summarized evidence from flare data from 2 LOS and 1 RCT supporting feasibility and content validity of flare domains. One-hour breakout groups allowed presentation of additional data and structured discussions to inform the research agenda. Reports from the breakout groups were then provided to the larger OMERACT group.

RESULTS

Preliminary Results from LOSs and RCTs

The Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort (CATCH) is a LOS which captures extensive clinical information and patient-reported outcomes every 3-6 months from 19 sites across Canada (19). 501 patients completed the flare questions at two consecutive visits. Of 39% who reported being in a flare at the visit the mean (SD) flare severity was 6.0 (2.6) and 67% reported flares > 7 days and 55% >14 days. Domain scores were compared by flare status (flare vs. no flare) using three flare classification systems: 1) patient-reported flare; 2) MD-reported flare; and 3) a DAS28-based definition (20, 21). Across all definitions, flare domain scores were, on average, at least twice as high among people classified as flaring vs. those not flaring, with clinically meaningful and statistically significant differences between groups. Correlations between domain scores and legacy items/scales (Health Assessment Questionnaire, Fatigue visual analogue scale, Veterans RAND-12 Health Survey, Worker Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire-Rheumatoid Arthritis, RA Disease Activity Index, and Patient Global) measuring similar constructs showed moderate to high agreement for pain (r’s ≥ .87), physical function (r’s ≥ .64), fatigue (r’s ≥ .72), participation (r’s ≥ .65) and stiffness (r’s ≥ .46) across flare definitions (see Table 1). The most common self-management strategies endorsed included taking additional analgesics (51%), and reducing (49%) or avoiding (32%) activities, with 5% indicating increasing use of steroids.

Table 1.

Relationship between OMERACT RA Flare Core Domains and legacy PRO measures or joint counts by flare status*

| Domains | All | Physician** | Patient*** | DAS28† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| N | Source | 501 | 148 | 253 | 124 | 377 | 49 | 264 |

| Pain | ||||||||

| How much pain due to RA in past week | HAQ | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.90 |

| Today’s level of pain today | RADAI | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.85 |

| Pain past week | Pt Global | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Joint area pain severity (0–48) | RADAI | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.75 |

| Patient Tender joint count (40) | Patient | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.57 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.63 |

| MD Tender joint count (28) | MD | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.51 |

| Physical Function | ||||||||

| Disability score (0–3) | HAQ | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.77 |

| Physical Function | RAND-12 | −0.68 | −0.68 | −0.61 | −0.71 | −0.60 | −0.64 | −0.67 |

| Daily activities in past 7 days | WPAI | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.81 |

| Fatigue | ||||||||

| Vitality (Rand-12) | RAND-12 | −0.62 | −0.60 | −0.65 | −0.64 | −0.59 | −0.69 | −0.61 |

| Unusual fatigue/tiredness past week | Pt Global | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.89 |

| Participation | ||||||||

| Role – Physical | RAND-12 | −0.72 | −0.65 | −0.71 | −0.69 | −0.66 | −0.70 | −0.67 |

| Social Function | RAND-12 | −0.61 | −0.67 | −0.60 | −0.72 | −0.49 | −0.68 | −0.61 |

| Productivity while working | WPAI | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.79 |

| RA affecting daily activities | WPAI | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.81 |

| Stiffness | ||||||||

| AM joint stiffness score | RADAI | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.71 |

Spearman correlation coefficients for second visit.

Physician endorsement of flare based on rating ≥ 0.5 cm on flare severity 100 mm VAS.

Patient classification of flare based on Yes/No.

DAS scores < 3.2 at second visit required an increase of 1.2 units whereas DAS ≥ 3.2 at second visit required increase of 0.6.

HAQ=Health Assessment Questionnaire-DI; RADAI=Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index; Pt. Global=Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity; VR-12=Veteran Rand-12 Health Survey; WPAI=Work Productivity and Activity Impairment-Rheumatoid Arthritis.

A combined flare definition (patient report of flare and DAS28 increase [DAS scores < 3.2 at second visit required an increase of 1.2 units whereas DAS ≥ 3.2 at second visit required increase of 0.6] (22)) was also evaluated with initial data from the RA-BIODAM, a 10-country LOS to validate biomarkers that predict joint damage and DRESS RCT (Dose Reduction Strategy of Subcutaneous TNF inhibitors in RA) (22). The overall flare rate was 14%; 56% had persisted > 7 days. Persons in flare scored significantly higher on all domains, ranging from 2.6 for stiffness to 3.6 for pain compared with 0.1 and 0.2 for stiffness and pain, respectively, in those not in flare. Patient-reported joint counts were also significantly higher in flare vs. no flare (tender joint count 6.0 vs 0.1, swollen joint count 4.3 vs 0.1; p<.001). In regression analyses, group differences persisted after adjustment for sex, age, disease duration, flare severity, and study type. Together, these data contribute new evidence of the feasibility of assessing flares with clinical and patient-reported data, and provide initial evidence of content validation of the RA Flare Core Domain Set.

Breakout Groups

OMERACT attendees were randomly assigned to 1 of 6 breakout groups; anyone could elect to attend a 7th group focused on methodological considerations. At the end of the breakout sessions, reports from each group were provided to all attendees outlining themes and recommendations that emerged for flare assessment.

Stiffness

Although stiffness was identified as a core RA flare domain, it remains unclear how to best assess stiffness. Results from focus groups with 20 participants (USA; (23)) and 16 individual interviews (UK; (24)) were presented. Findings suggested that people with RA described the experience of stiffness in terms of severity and impact throughout the day, rather than as the duration of morning symptoms.

The 36 participants broke into two smaller groups and there was agreement that querying only morning stiffness duration may not adequately capture patients’ experiences and does not address impact. There was agreement that it may be helpful to expand current conceptualizations of stiffness, and there was interest in creating a Special Interest Group for stiffness across rheumatic diseases ((25).).

Self-Management

Participants in two groups agreed that self-management (e.g., use of steroids, analgesics) can affect the intensity/duration of flare symptoms and impacts. In one (n=16), most (13/15) viewed self-management as a core flare domain, while in the other (n=7) opinions were divided about whether self-management was best conceptualized as a core domain or contextual factor. Participants noted no measures currently exist to query self-management strategies commonly used in RA. The groups felt that the self-management question we used did not sufficiently cover the range of self-management activities RA patients use, required a validated scoring strategy, and would need to detect practices beyond what the person usually does (e.g., taking additional analgesics, reducing/avoiding activities, etc.) While overlap between self-management and coping was recognized, it was concluded these represent currently ill-defined but different constructs and that further study was needed to assess self-management across rheumatic conditions.

Contextual factors

OMERACT Filter 2.0 requires the identification of key contextual factors to include in outcome measurement models (26). Two breakout groups (n=10 and n=8) identified and prioritized potential flare contextual factors in RCTs and LOSs.

Contextual factors are factors that are not the primary focus of the research, but may influence interpretation of the results (26). A wide range of factors that could potentially impact outcomes were discussed including RA-, comorbidity-, person-, and therapy-specific factors. There was uncertainty about how to identify contextual factors, the extent to which they are applicable across settings, and whether they contribute unique information that is required to interpret flare assessment results. Filter 2 notes that a contextual factor can be declared ‘core’ when it significantly modifies intervention outcomes; self-management is cited as an example. There was strong endorsement in these groups for a separate effort to address defining and measuring contextual factors in other conditions.

Measurement Considerations in Evaluating Flares

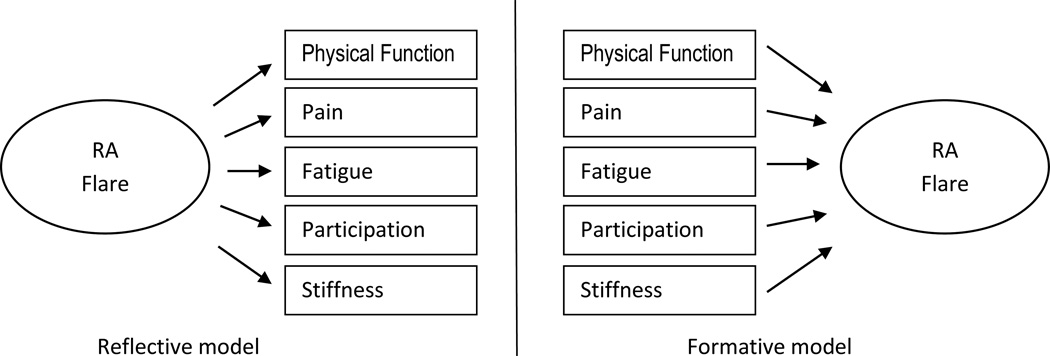

Discussion in the measurement breakout, attended by 22 participants, centered around several themes. The current flare definition, which ties the identification of flare to specific actions (i.e., consideration of treatment change), is potentially problematic. The relative value of characterizing flare as an extension of disease activity (e.g., a change in the DAS28 vs. as a separate construct) was also debated. There was agreement that it was important to determine whether flare conceptual models should be reflective (i.e., core domains serve as flare indicators) or formative (i.e., flare summarizes variation in core domains) (18) (see Figure 1). To evaluate evidence of unidimensionality (i.e., that flare might be represented using a single summative score of domains), additional analyses were recommended. Specific questions were voted on during the session. Most (17/22) agreed that both traditional (Classical Test Theory) and modern measurement methods (e.g., item response theory, Rasch theory) should be considered when developing any new measure. Almost all (20/22) agreed that flare reflects a change in state that persists for a specific duration, but it was less clear how much worsening was required over how many days, and whether increases in disease activity should be evaluated relative to current levels and/or prior state.

Figure 1.

RA flare represented as a reflective or formative model.

There was consensus that agreement of flare status by both patients and HCPs increased confidence the person was experiencing an inflammatory flare. For clinicians, a binary classification system may be desirable (flare vs. not in flare). There was also general agreement that over-diagnosis of flare could result in over-treatment and that the relative balance of specificity vs. sensitivity may vary by setting (e.g., clinical care vs. RCTs). Finally, some voiced concern that development of a separate flare assessment tool, if paper-based and required to be administered at each visit, could be burdensome to patients and staff.

CONCLUSION

Since OMERACT 10, the RA Flare Group has developed methods and assembled an international group of collaborators to collect flare data in ongoing LOSs and RCTs. We presented results from initial data collected that supports the feasibility and content validity of the RA Flare Core Domain Set and demonstrated the prevalence, symptoms and impact of RA flares. Breakout group discussions noted potential research needs around assessing stiffness and self-management, and the need to clarify methods to evaluate contextual factors across settings. Opinions ranged on whether self-management is a core domain, contextual factor or both.

The research agenda for OMERACT 2016 includes utilizing flare data currently being collected in multiple international studies to identify: 1) appropriate anchors for flare assessment including agreement (patient/MD, patient/DAS criteria); 2) duration and intensity thresholds; and 3) factors associated with disagreement regarding flare status between patients and providers. Additional work is being conducted by our group to establish the incremental value of the additional RA flare domains over the RA core set in assessing flare, the need for new measures of selected domains (e.g., stiffness, participation, self-management), recommended cut points to assess flare using existing measures, and opportunities to integrate flare assessments in patient self-management and RA care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank additional patient research partners and flare working group collaborators for their ongoing participation in this work, and all leaders and investigators involved in CATCH, BIODAM, DRESS and other ongoing studies that are collecting flare data for analysis. We thank Alfons den Broeder, Aatke van der Maas and Walter P. Maksymowych for providing initial flare results for preliminary analysis and Daming Lin for CATCH analyses.

The CATCH study was designed and implemented by the investigators and financially supported initially by Amgen Canada Inc. and Pfizer Canada Inc. via an unrestricted research grant since the inception of CATCH. As of 2011, further support was provided by Hoffmann-LaRoche Ltd., UCB Canada Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada Co., AbbVie Corporation (formerly Abbott Laboratories Ltd.), and Janssen Biotech Inc. (a wholly owned subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson Inc.).

Additional support for this work has been provided by Roche Canada, Pfizer (US, Europe, Canada), Novartis, Abbvie/Genentech, Crescendo, Dxterity Diagnostics, Acetlion, Janssen and UCB (translation of flare questions).

COB is a member of the executive committee for OMERACT, an organization involved in clinical outcome measure development and validation, which receives arms-length funding from 23 pharmaceutical and clinical research companies. He currently serves or has served in the past as a consultant to the following companies regarding clinical trial outcome measurement: Abbvie, Amgen, BMS, Genentech/Roche, Janssen, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Christensen is supported by grants from Oak Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alten R, Pohl C, Choy EH, Christensen R, Furst DE, Hewlett SE, et al. Developing a construct to evaluate flares in rheumatoid arthritis: a conceptual report of the OMERACT RA Flare Definition Working Group. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1745–1750. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bingham CO, 3rd, Alten R, Bartlett SJ, Bykerk VP, Brooks PM, Choy E, et al. Identifying preliminary domains to detect and measure rheumatoid arthritis flares: report of the OMERACT 10 RA Flare Workshop. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1751–1758. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bingham CO, III, Pohl C, Alten R, Christensen R, Choy EH, Hewlett SE, et al. Flare and disease worsening in rheumatoid arthritis: time for a definition. Int J Adv Rheumatol. 2009;7:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bykerk VP, Lie E, Bartlett SJ, Alten R, Boonen A, Christensen R, et al. Establishing a core domain set to measure rheumatoid arthritis flares: report of the OMERACT 11 RA flare Workshop. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:799–809. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingham CO, 3rd, Pohl C, Woodworth TG, Hewlett SE, May JE, Rahman MU, et al. Developing a standardized definition for disease "flare" in rheumatoid arthritis (OMERACT 9 Special Interest Group) J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2335–2341. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631–637. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, Kremer JM, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:625–639. doi: 10.1002/acr.21641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Maas A, den Broeder AA. Measuring flares in rheumatoid arthritis. (Why) do we need validated criteria? J Rheumatol. 2014;41:189–191. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewlett S, Sanderson T, May J, Alten R, Bingham CO, III, Cross M, et al. 'I'm hurting, I want to kill myself': rheumatoid arthritis flare is more than a high joint count--an international patient perspective on flare where medical help is sought. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:69–76. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartlett SJ, Hewlett S, Bingham CO, 3rd, Woodworth TG, Alten R, Pohl C, et al. Identifying core domains to assess flare in rheumatoid arthritis: an OMERACT international patient and provider combined Delphi consensus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1855–1860. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berthelot JM, De BM, Morel J, Benatig F, Constantin A, Gaudin P, et al. A tool to identify recent or present rheumatoid arthritis flare from both patient and physician perspectives: The 'FLARE' instrument. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1110–1116. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.150656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bingham CO, 3rd, Alten R, de Wit MP. The importance of patient participation in measuring rheumatoid arthritis flares. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1107–1109. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gossec L, Dougados M, Rincheval N, Balanescu A, Boumpas DT, Canadelo S, et al. Elaboration of the preliminary Rheumatoid Arthritis Impact of Disease (RAID) score: a EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1680–1685. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.100271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S. What outcomes from pharmacologic treatments are important to people with rheumatoid arthritis? Creating the basis of a patient core set. Arthritis Care & Research. 2010;62:640–646. doi: 10.1002/acr.20034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1995;38:727–735. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirwan JR, Bartlett SJ, Beaton DE, Boers M, Bosworth A, Brooks PM, et al. Updating the OMERACT filter: implications for patient-reported outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1011–1015. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tugwell P, Boers M, D'Agostino MA, Beaton D, Boonen A, Bingham CO, III, et al. Updating the OMERACT filter: implications of filter 2.0 to select outcome instruments through assessment of "truth": content, face, and construct validity. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1000–1004. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL. Measurement in medicine: a practical guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bykerk VP, Jamal S, Boire G, Hitchon CA, Haraoui B, Pope JE, et al. The Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort (CATCH): patients with new-onset synovitis meeting the 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria but not the 1987 ACR classification criteria present with less severe disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:2071–2080. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Maas A, Lie E, Christensen R, Choy E, de Man YA, van RP, et al. Construct and criterion validity of several proposed DAS28-based rheumatoid arthritis flare criteria: an OMERACT cohort validation study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1800–1805. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Maas A, Lie E, Christensen R, Choy E, de Man YA, van Riel P, et al. Construct and criterion validity of several proposed DAS28-based rheumatoid arthritis flare criteria: an OMERACT cohort validation study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1800–1805. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.den Broeder AA, van Herwaarden N, van der Maas A, van den Hoogen FH, Bijlsma JW, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Dose REduction strategy of subcutaneous TNF inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: design of a pragmatic randomised non inferiority trial, the DRESS study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orbai AM, Smith KC, Bartlett SJ, de LE, Bingham CO., III "Stiffness has different meanings, I think, to everyone": examining stiffness from the perspective of people living with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014 May 28; doi: 10.1002/acr.22374. 10.1002/acr.22374 [doi]. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halls S, Dures E, Kirwan J, Pollock J, Baker G, Edmunds A, et al. Stiffness is more than just duration and severity: a qualitative exploration in people with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2014 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu379. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu379 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orbai AM, Halls S, Hewlett S, Bartlett SJ, Leong A, Bingham CO., III More than just minutes of stiffness in the morning: Report of the Rheumatoid Arthritis Flare Group on stiffness breakout sessions. J Rheumatol. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141172. in press (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boers M, Idzerda L, Kirwan JR, Beaton D, Escorpizo R, Boonen A, et al. Toward a generalized framework of core measurement areas in clinical trials: a position paper for OMERACT 11. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:978–985. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]