Abstract

Flavin-dependent, lysine-specific protein demethylases (KDM1s) are a subfamily of amine oxidases that catalyze the selective posttranslational oxidative demethylation of methyllysine side chains within protein and peptide substrates. KDM1s participate in the widespread epigenetic regulation of both normal and disease state transcriptional programs. Their activities are central to various cellular functions, such as hematopoietic and neuronal differentiation, cancer proliferation and metastasis, and viral lytic replication and establishment of latency. Interestingly, KDM1s function as catalytic subunits within complexes with coregulatory molecules that modulate enzymatic activity of the demethylases and coordinate their access to specific substrates at distinct sites within the cell and chromatin. Although several classes of KDM1 -selective small molecule inhibitors have been recently developed, these pan-active site inhibition strategies lack the ability to selectively discriminate between KDM1 activity in specific, and occasionally opposing, functional contexts within these complexes. Here we review the discovery of this class of demethylases, their structures, chemical mechanisms, and specificity. Additionally, we review inhibition of this class of enzymes as well as emerging interactions with coregulatory molecules that regulate demethylase activity in highly specific functional contexts of biological and potential therapeutic importance.

Keywords: KDM1A, KDM1B, Epigenetic, LSD1, LSD2

INTRODUCTION

The functional capacity of genetically encoded proteins can be powerfully expanded by reversible posttranslational modifications (PTMs). Protein side chain covalent modifications such as methylation, phosphorylation, acetylation, glycosylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, ADP-ribosylation, nitrosylation, carboxylation, and sulfonation, among others, can potentiate local and global protein architecture and generate novel reactive functional groups for binding and catalysis. Additionally, these modifications can generate signals for cellular compartmentalization and confer alterations to physiochemical properties such as stability, solubility, and resistance to proteolytic degradation. Such modifications are intimately integrated into all aspects of modulating cellular proliferation and biological recognition.

Allfrey first linked histone acetylation and methylation to the control of RNA synthesis in 1964.1,2 Since that time, it has become clear that protein and histone methylation is a pervasive cellular regulatory mechanism. Specifically, protein lysine methylation status plays a critical role in biology and pathobiology by influencing transcriptional activation and repression, chromatin remodeling, normal and oncogenic signaling, viral pathogenesis, and protein and transcription factor recruitment, among other functions. S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases (SAM-dependent MTases) catalyze the installation of lysine methyl marks, forming mono-, di-, and tri-methylated side chain PTMs. These marks are removed by two mechanistically-distinct classes of lysine-specific demethylases (KDMs) that utilize either a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor (KDM subfamily 1) or iron(II) and α-ketoglutarate cofactors (KDM subfamily 2–6) to catalyze the oxidative demethylation of protein side chains.3–5

For decades, methylation marks on proteins like histones were presumed to be immutable, reversed only through protein turnover and degradation. The first hints of a candidate histone demethylase enzyme emerged in 1998 and again in 2001, when several histone deacetylase (HDAC)-containing complexes were discovered to associate with KIAA0601 (aka KDM1A/LSD1/ BHC110/AOF2), a protein with homology to human FAD-dependent oxidoreductases (MAO-A/B) and maize polyamine oxidase (mPAO) (Figure 1a), enzymes that catalyze the oxidative cleavage of C-N bonds.6–8 In 2003, Shiekhattar reported that BHC110/KIAA0601 formed a stable complex with several proteins, including HDACs 1 and 2, CoREST, BRCA2-associated factor, BCH80, TFII-1, KIAA0182/GSE-1, ZNF217, ZNF198/FIM and ZNF261/X-FIM.9

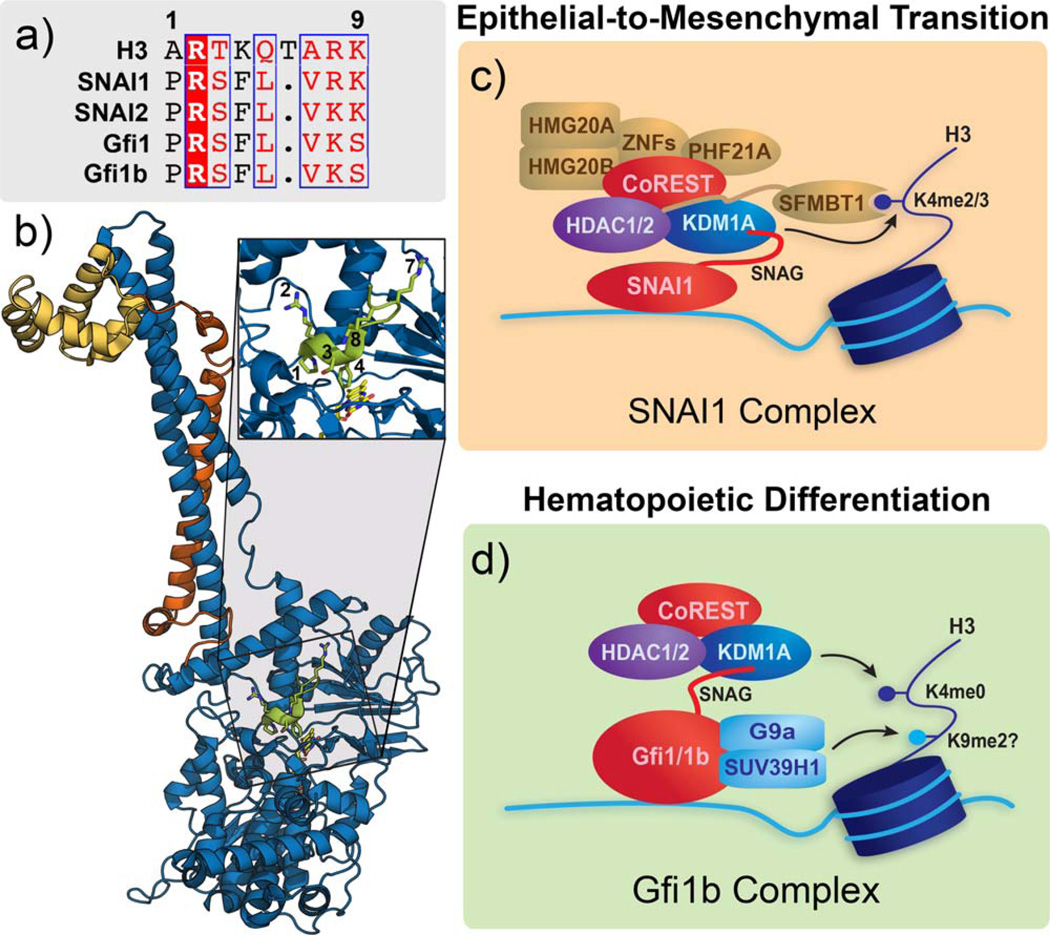

FIGURE 1.

Structural overview of KDM1 demethylases. (a) Sequence alignment of a portion of the amine oxidase domains of KDM1A, KDM1B, MAO-A, MAO-B, and maize polyamine oxidase (mPAO). Sequence conserved active site Lys residue is starred. (b) Domain maps of KDM1A and KDM1B. SWI3p, Rsc8p, and Moira (SWIRM) domains shown in green, amine oxidase domains shown in blue, tower domain shown in lavender, linker domain shown in teal, C4H2C2 domain shown in purple, and Zf-CW domain shown in orange. (c) Ribbon representation of the structure of KDM1A. Domains follow same color scheme as outlined above (PDB 2IW5). (d) Ribbon representation of the structure of KDM1B. Domains follow same color scheme as outlined above (PDB 4HSU). (e) Venn diagram of domain conservation between KDM1A and KDM1B.

In 2003 Amasino and coworkers independently discovered that the gene FLOWERING LOCUS D (FLD) encoded a plant homolog of KIAA0601.10 FLD is one of six genes in the Arabidopsis thaliana autonomous floral-promotion pathway that initiates the transition from a vegetative to reproductive state by repression of the MADS-box transcription factor FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC). FLD not only contains a KIAA0601-like amine oxidase domain, but also possesses an N-terminal SWI3p, Rsc8p, and Moira (SWIRM) domain similar to that associated with a range of proteins involved in chromatin remodeling, including KIAA0601.11,12 Deletion of FLD in A. thaliana results in hyperacetylation of histones in the FLC locus, upregulation of FLC expression, and extremely delayed flowering, suggesting that the autonomous pathway involves regulation of histone deacetylase activity by FLD.10 Deletion of FLD also resulted in increased histone methylation levels (R. Amasino, personal communication), implicating FLD (and by analogy KIAA0601) as the elusive human histone demethylase enzyme.

In early 2004, Shi and coworkers provided the first direct evidence that KIAA0601 (from here on referred to as KDM1A) functions as a histone demethylase and transcriptional corepressor.13 The authors reveal that KDM1A specifically demethylates mono- and di-methylated histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me1/ 2), a histone mark linked to active transcription, and that lysine demethylation occurrs via an oxidative reaction that generates formaldehyde. In addition, loss of KDM1A through siRNA knockdown results in increased H3K4 methylation and concomitant derepression of several neuronal-associated target genes. Shi’s discovery of KDM1A activity implied that lysine methylation might be dynamically controlled.

The second human flavin-dependent histone demethylase, KDM1B (aka LSD2/AOF1) was identified by Shi and coworkers in 2004 through a domain homology search of genomic databases.13 Mattevi and coworkers first isolated and confirmed the flavin-dependent demethylation activity of KDM1B, noting specificity for H3K4me1/2, despite the relatively low sequence identity (<25%) with KDM1A.14 Unlike KDM1A, KDM1B does not form a biochemically-stable complex with the C-terminal domain of the corepressor CoREST, but does possess both CW-type and C4H2C2-type zinc finger motifs. This suggests that KDM1B may interact with different targets or coregulatory molecules and may be involved in transcriptional programs distinct from those of KDM1A.

Herein we review the biological function, biochemical characterization, and inhibition of this enzyme class to date. First, we briefly discuss the biological importance and therapeutic potential of KDM1s. This is followed by the structural organization, chemical mechanism, and substrate specificity of the KDM1 enzymes. We then outline the various inhibitor classes that have been developed for these demethylases, specifically highlighting the utility of peptide-based inhibitors. Finally, we describe the known interactions between the KDM1s and regulatory biomolecules, which direct their activity toward specific cellular pathways. Given the wide-ranging and ubiquitous functions of this enzyme class, probes with the ability to target KDM1 activity in a manner that is pathway-specific would be of heuristic and therapeutic value. We see these coregulatory molecules as a valuable starting point for the development of such probes, as underscored by the recent development of peptide inhibitors of this enzyme class.

KDM1A AND KDM1B BIOLOGYAND THERAPEUTIC POTENTIAL

KDM1A is involved in a wide variety of cellular processes and pathologies, including signal transduction, chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, development, differentiation, viral pathogenesis, and cancer proliferation and metastasis.3,15–23 As such, KDM1 demethylases have emerged as potential therapeutic targets. Although their clinical value is only beginning to be explored, at the time of this review’s publication, five clinical trials involving KDM1A were either planned or currently recruiting subjects. Three trials will investigate KDM1A inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), one will evaluate the same strategy in small cell lung cancer, and one seeks to correlate the status of KDM1A with cardiovascular responses to changes in sodium intake (see http://clinicaltrials.gov). We expect the scope of clinical trials to expand with our growing knowledge of KDM1A function.

Cellular Differentiation

Epigenetic modifications are critical for the maintenance of pluripotent stem cells and their subsequent differentiation into specialized tissues.24–26 Specifically, KDM1A is an integral part of the cellular machinery that governs differentiation processes in various cell types, including embryonic,27,28 hematopoietic,23,29–33 neuronal,34–38 pituitary,39 and osteogenic.40 While KDM1A activity is critical for proper development, aberrant regulation can contribute to tissue-specific disease states. For example, KDM1A activity has been linked to neuronal cell proliferation and survival41,42 and long-term memory formation,43 and is therefore an emerging therapeutic target for some neurological and cognitive disorders. Similarly, recent work has also identified KDM1A as a key regulator of leukemia stem cells,44 sparking interest in its potential as a therapeutic target in AML (see below), among other hematopoietic-related diseases.45

Cancer Development and Progression

KDM1A has also been widely implicated in the development and progression of cancer. In addition to the malignancies described in detail below, KDM1A is emerging as a potential therapeutic target in various other cancer types.46–56

Neuroblastoma

Overexpression of KDM1A in neuroblastic tumors correlates with poor prognosis57 and may be related to the aberrant downregulation of KDM1A-silencing micro-RNAs.58,59 Schulte and coworkers first noted in 2009 that KDM1A inhibition in neuroblastoma cells leads to increased H3K4 methylation, decreased proliferation in cell culture, and reduced tumor growth in a xenograft model.57 Similarly, KDM1A inhibitors synergize with retinoic acid, a currently approved treatment for neuroblastoma.60 A later report demonstrated similar results in the closely-related medulloblastoma tumor type, where KDM1A inhibition decreases proliferation and initiates apoptosis.61

Colorectal Cancer

KDM1A is also an emerging target in colorectal cancers, where it is markedly overexpressed in tumor samples compared to matched normal tissue62 and exhibits a positive correlation with metastatic potential.63,64 Although genetic deletion of KDM1A does not result in a global increase of H3K4me2, it does alter gene expression programs and reduces proliferation in cell culture and in vivo.62,65 KDM1A may also promote colorectal cancer progression by derepressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, a known regulator of tumorigenesis.62

Leukemia

KDM1A is also a promising target for pharmacological intervention in leukemia. For example, KDM1A inhibition alone provokes cytotoxic effects in AML cell lines,66 and when used in conjunction with HDAC inhibitors, reduces tumor engraftment and improves survival in mice.67 KDM1A inhibition also unlocks the anti-leukemic effects of all-transretinoic acid (ATRA), a differentiation-inducing agent that otherwise is ineffective for the treatment of AML.68 KDM1A has been implicated in other leukemia subtypes as well. In a model of MLL-AF9 leukemia cells, KDM1A cooperates with the MLL MTase fusion protein to maintain an oncogenic transcription program, and KDM1A inhibitors preferentially reduce the repopulation potential of MLL-AF9 cells over normal hematopoietic cells.44 Interestingly, Spruüssel and coworkers evaluated the potential side effects of KDM1A inhibition in leukemia and found that while a conditional KDM1A knockdown significantly alters existing pools of normal hematopoietic tissues, these effects are largely reversible following reinstatement of the demethylase.31 For a more detailed discussion of KDM1A’s function and therapeutic potential in leukemia, we refer readers to a recent review by Mould and colleagues.69

Breast Cancer

KDM1A has also been implicated as a regulator of breast cancer development and progression. The majority of the breast tumors are estrogen-dependent, making estrogen antagonists one of the most commonly employed therapies. However, circumvention of estrogen signaling, such as through loss of estrogen-receptor alpha (ERα), can lead to hormone-resistant tumors, reduced treatment options, and worse prognosis. KDM1A is generally associated with a more aggressive breast cancer phenotype and may be overexpressed in both ERα-positive and -negative cells,70–73 possibly due to aberrant stabilization of the demethylase.74 Correspondingly, several groups have reported that KDM1A inhibition decreases proliferation of breast cancer cells.70,72,75 Notably, at least two groups have reported contradicting results that suggest KDM1A may be downregulated in breast cancer tissue and that inhibition affects metastasis with no observable effects on proliferation.76,77 KDM1A inhibition may also have therapeutic effects when used in conjunction with anti-estrogen treatment78 and HDAC inhibitors.79,80

Prostate Cancer

A similarly vague relationship exists between KDM1A and prostate cancer. One study reported a correlation between KDM1A expression and risk of recurrence,81 while at least two other studies have noted little to no overexpression of KDM1A in prostate cancer cell lines and tumor samples.82,83 However, Metzger and coworkers have linked KDM1A activity to transcriptional regulation with the androgen receptor (AR), a nuclear hormone receptor closely linked with prostate cancer.84 Likewise, KDM1A inhibition appears to impede AR-mediated transcription and prostate cancer proliferation.84–87 A review detailing further the roles of demethylases in prostate cancer has recently been published.88

The Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition

In addition to these roles in specific cancer types, KDM1A is also intimately linked with the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), the process by which a polarized, adhesive epithelial cell transitions into a motile, invasive mesenchymal phenotype. The importance of epigenetic mechanisms during the EMT is only beginning to be appreciated.89 KDM1A is an established functional partner of the EMT master regulator SNAI1 and cooperates to silence epithelial genes.90 KDM1A also regulates upstream inducers of the EMT,91 including TGFβ,76,92,93 Wnt,62,94 NF-κB,80 and Notch.95,96 Through these and potentially other mechanisms, KDM1A participates in large-scale chromatin remodeling events that accompany the EMT.92

The EMT is a hallmark of aggressive cancers with a high risk of metastasis, potentially implicating KDM1A as a therapeutic target.89 Accordingly, KDM1A inhibition in AML models produces morphological features of differentiation in primary and cultured cells,67 derepresses differentiation-associated genes, 66,68 and reduces engraftment of primary cells in a mouse model.68 Similar effects are observed in MLL-AF9 leukemia and neuroblastoma models.44,57 Furthermore, KDM1A activity is associated with increased metastatic potential and its inhibition or knockdown decreases migration and invasion in several cancer types,48,49,63,64 with again conflicting reports concerning breast cancer.76,97,98

Viral Pathogenesis

Lastly, KDM1A is associated with herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection and replication, as HSV hijacks KDM1A-containing machinery required for human neuronal gene repression during host infection. Cooption of KDM1A demethylase activity helps promote early stage (α) viral gene activation, regulates late stage (β/γ) viral gene repression, and has been linked to gene repression during the development of HSV latency, the process by which viruses enter and emerge from dormancy in infected host cells.99 Kristie and coworkers recently demonstrated that interruption of KDM1A activity potently represses HSV immediate-early (IE) gene expression and genome replication, resulting in suppression of primary infections and subsequent reactivation from latency in murine infection models.100–102 In addition, KDM1A activity may play a similar role in the infection processes of several other viruses.101,103,104 Collectively, these studies underscore the emerging importance of KDM1A as an antiviral target.

Emerging Biological Roles for KDM1B

The biological roles of KDM1B are beginning to emerge; however, our current understanding of this enzyme lags far behind that of KDM1A. In general, KDM1B is believed to function as an enhancer of gene transcription that functions in highly transcribed coding regions of chromatin.105 Although mechanistic data is not yet available, KDM1B has been linked to genomic imprinting,106 liver development,107, somatic cell reprogramming,108,109 and NF-κB signaling.110 Future research will likely reveal a broader set of KDM1B-dependent biological processes.

DOMAIN ORGANIZATION AND STRUCTURAL FEATURES OF KDM1 DEMETHYLASES

KDM1A Demethylase

KDM1A is an 852 amino acid (aa) polypeptide composed of three domains: an amine oxidase catalytic domain (AOD) (residues 272–415 and 515–852), an ~100 aa insert known as the “tower” domain (residues 415–515), and a SWIRM domain (residues 172–272) (Figure 1b,c).11,111,112 The N-terminal region of the enzyme (~170 aa) has no predicted conserved structural elements, but does contain a nuclear localization signal (RRKRAK; residues 112–117) for nuclear import via importin-α translocases.113,114 The three-dimensional structure of KDM1A has been solved by X-ray crystallographic methods in the unliganded form and in complex with varying ligands, including peptides and inhibitors.111,112,115–126 The AOD of the enzyme contains a single non-covalently bound FAD molecule and bears similarity to human MAO-A/B and mPAO (17.6%, 17.6%, and 22.4% sequence identity, respectively; Figure 1a).127 Consistent with other flavin-dependent amine oxidases,128,129 the AOD can be further subdivided into two separate lobes, where residues 357–415, 515–558, and 658–769 are involved in substrate binding and residues 272–356, 559–657, and 770–852 form an expanded Rossmann fold used to bind FAD.112,115

The tower domain of KDM1A is an antiparallel coiled-coil composed of two α-helices (termed TαA and TαB) bridged by a tight turn formed by a KPPRD sequence.112 This domain projects almost 100 Å from the AOD and functionally is the site of association with corepressor CoREST (aka RCOR1/KIAA0071), among other proteins.112,115,130 The SWIRM domain of KDM1A is predominantly a bundle of α-helices, with a long central α-helix that separates two smaller helixturn-helix motifs (Figure 1c).111 This domain also engages the C-terminal tail of the AOD with a highly hydrophobic interface that buries a surface area of ~1,700 Å2.111 Mutations of conserved residues along this interface have been shown to reduce the catalytic activity of KDMA1 and its stability.111

Although SWIRM domains are highly conserved amongst chromatin associating proteins and have been shown to bind DNA, ,12,131 this is not the case in KDM1A. The residues that compose the typical DNA-binding interface (α6; residues 247–259) are not conserved and are partially blocked by their interaction with the AOD.111,115 Accordingly, neither KDM1A nor the isolated SWIRM domain binds DNA.115,132

In addition, Luka and coworkers showed that KDM1A binds to the small molecule tetrahydrofolate with a Kd of 2.8 µM, and recently reported the crystal structure of the KDM1A-CoREST-tetrahydrofolate complex.126,133 In this complex, the folate binds in the active site in close proximity to the FAD cofactor, and overlaps with the peptide-binding site observed by Forneris.117 Luka and coworkers also detected the production of 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate by mass spectrometry following incubation of KDM1A with a H3K4-derived methylated peptide substrate and tetrahydrofolate. From this data, it was postulated that tetrahydrofolate binding might protect the cell from potentially toxic formaldehyde or regulate access of the substrate to the FAD within the active site. It is not known at this time if KDM1B exhibits a similar ability to bind tetrahydrofolate.

KDM1B Demethylase

The closely related KDM1B is an 822 aa flavoenzyme amine oxidase that contains a predicted unordered N-terminus and a nuclear localization signal (~50 aa) responsible for its residence within the nucleus of human cells.106 KDM1B is organized into three domains: an N-terminal dual zinc finger domain (residues 50–264), a SWIRM domain (residues 264– 372), and a C-terminal catalytic AOD (residues 372–822; Figure 1b,d). 134–136 In the substrate-free structure of KDM1B, the zinc fingers and catalytic AOD are packed closely against a central SWIRM domain (Figure 1d), collectively resembling a boot.134 Comparison of the AOD between KDM1A and KDM1B (33% sequence identity) shows that many secondary structural elements are conserved, including strong conservation of the catalytic architecture around the FAD-binding site. 134 However, when comparing the AODs through structural alignment, there is a 2.0 Å RMSD difference in the overall polypeptide backbone conformation. These structural differences are mostly attributed to the length and conformation of solvent exposed loops within the domain.134 Despite these differences, the similarity of the AODs of KDM1A and KDM1B argues for a common chemical mechanism for catalysis.

Structural Differences Between KDM1A and KDM1B

Despite catalyzing identical chemical reactions and sharing significant AOD structural similarity, KDM1A and KDM1B have several structurally important differences. For example, the SWIRM domains of both enzymes only share 24% sequence identity. Although helices within this domain are qualitatively positioned, significant differences have been observed at both solvent exposed interfaces along the helical termini. Since the entrance to the AOD active site lies at the interface of the AOD and SWIRM domains, structural and sequence differences at this interface are suspected to impact substrate specificity of each isoform.134

Indeed, at this interface the SWIRM-AOD subdomain interactions differ in several aspects when comparing KDM1A to KDM1B. Notably, the SWIRM domain of KDM1B closely packs against the N-terminal zinc finger domain, burying a surface area of 1,872 Å2. 134 As compared to KDM1A, the SWIRM domain of KDM1B lacks a C-terminal helix (KDM1A; residues 171–181), but is replaced by an extended, coiled loop (KDM1B; residues 271–281).136 This substitution in KDM1B leads to the formation of two additional hydrogen bonds (E452 with N266, and Y268 with D571) and one electrostatic interaction (E323 with K323) that may influence the degree of association among these domains.136 Not only does this loop provide additional intramolecular interactions, but also forms a second binding site for the N-terminal tail of histone H3.135

The most striking structural difference between KDM1A and KDM1B is the inclusion of distinct domains that mediate interactions with other biomolecules (Figures 1b,e). KDM1A contains an α-helical, antiparallel coiled-coil tower domain that is absent in KDM1B (Figure 1c – e). DALI137 structural similarity analyses indicate that the tower domain fold appears infrequently among known eukaryotic protein structures, with the PI3Kα-p85α subunit complex (PDB 3HHM)138 and the DNA double-strand break repair ATPase RAD50 (PDB 1L8D)139 bearing the closest structural similarity. In contrast, the tower fold was heavily represented among a subset of prokaryotic proteins known to utilize such motifs as part of inter-molecular protein recruitment, membrane docking, and membrane translocation functions.140

Although KDM1B does not contain a tower domain, it does contain two individual zinc fingers and two linker domains that are not reflected in the structure of KDM1A (Figure 1b,e). At the N-terminus of KDM1B, a C4H2C2-type zinc finger is joined to a second CW-type zinc finger (Zf-CW) by a linker formed from two α-helices (Figure 1b,d). Immediately following the Zf-CW domain, a second linker formed by four α-helices joined through several large loops bridges these domains to the AOD.134–136 The surface of the C4H2C2-type zinc finger shows a marked concentration of basic residues, and thus may impact demethylase substrate specificity or positioning within nucleosomal DNA. Additionally, these residues may facilitate interactions with coregulatory molecules or serve to recruit transcriptional machinery, such as phosphorylated RNA polymerase II.105,134 Interestingly, it appears that the zinc finger domain of KDM1B is required for histone demethylation activity. Wong and coworkers suggest that mutations which disrupt the zinc finger domains or relays of interactions among the zinc finger-SWIRM-AOD likely lead to subtle conformational alterations in the AOD that in turn impair the incorporation of FAD, and consequently its enzymatic activity.134

Furthermore, although zinc fingers are common folding motifs, the Cys2A-Cys2B-His2A-Cys2B sequence within KDM1B folds into a cross-brace topology that has not been previously observed, raising the possibility that this domain may participate in biomolecular interactions that are exclusive to KDM1B.134 On the other hand, the Zf-CW of KDM1B bears significant sequence similarity to CW-type zinc finger domains, a class linked to histone H3 binding. Despite this, as an isolated recombinant domain, the KDM1B Zf-CW fails to bind histone H3-derived peptides (residues 1–21 containing H3K4me1/2 or unmethylated H3K4), which is atypical to behavior exhibited by other isolated Zf-CW domains.134,136 However, since ligand binding within Zf-CW domains is mediated by interactions within a well-conserved hydrophobic cleft, which happens to be absent in the KDM1B Zf-CW domain structure, this may partially explain its inability to bind histone H3 peptides.

Taken together, the exclusive presence of the tower domain in KDM1A and the zinc finger motifs in KDM1B strongly suggest that these two demethylases share a related chemical mechanism, but likely participate in associations with non-identical sets of interacting partner biomolecules. These partners may influence individual catalytic activity, substrate specificity, or localization of these enzymes within genetic loci.

CHEMICAL MECHANISM OF KDM1-FAMILY FLAVIN-DEPENDENT DEMETHYLASES

KDM1A and KDM1B are Mechanistically Distinct from Iron(II)-Dependent Lysine-Demethylases

KDM1 family human demethylases utilize a FAD cofactor to oxidize C-N bonds with subsequent production of a demethylated lysine residue and formaldehyde by product.141 By contrast, KDM subfamilies 2–6 (Jumonji-C domain-containing demethylases) are mechanistically distinct from the KDM1s since they utilize non-heme iron(II) and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) cofactors to demethylate lysine residues with the concomitant production of succinate and formaldehyde.4 KDM families 2–6 are also distinguished from KDM1A and KDM1B by their unique ability to demethylate trimethylated lysine residues.142 However, KDM1 flavoenzymes have a mechanistic requirement of a protonated iminium intermediate, achievable only with mono- and dimethylated lysines.

Involvement of Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide as a Cofactor

Experimental and theoretical mechanistic studies have been conducted on flavin-utilizing KDMs, focusing almost exclusively on KDM1A. Mattevi and coworkers first confirmed the participation of the non-covalent FAD in the demethylation reaction using two truncated forms of KDM1A lacking the first N-terminal 157 or 184 aa.143 They visualized production of the two-electron fully reduced flavin, noting the absence of intermediate one-electron reduced forms of the cofactor. This suggested that KDM1A was likely related by mechanism to the broader family of flavoenzyme oxidases that catalyze two-election oxidation of substrates with concomitant cofactor reduction.143 Once the substrate is oxidized, hydrolysis by bulk solvent of the iminium intermediate produces an unstable hemiaminal that spontaneously decomposes into formaldehyde and the mono-demethylated product. Additionally, reoxidiation of the FAD cofactor by molecular oxygen produces a molar equivalent of H2O2 and the fully oxidized quinone (Scheme 1).13,143

SCHEME 1.

Proposed chemical mechanism of FAD-dependent demethylases KDM1A and KDM1B. Oxidation of the C-N bond of the methylated lysine sidechain to an iminium ion, with concurrent reduction of the flavin enables hydrolysis via bulk water. Collapse of the hemiaminal (not shown) yields formaldehyde and the demethylated amine sidechain. The reduced flavin is reoxidized by molecular oxygen, generating a molar equivalent of hydrogen peroxide.

Evidence for a Direct Hydride Transfer Mechanism

McCafferty, Fitzpatrick, and coworkers conducted a detailed investigation of the chemical mechanism of KDM1A.144,145 The mechanism was examined using the effects of pH and isotopic substitution on steady-state and pre-equilibrium kinetic parameters. Using a 21-mer derived from histone H3 (H3K4me2, residues 1–21) at pH 7.5, the rate constant for flavin reduction in the transient phase, kred, was shown to equal kcat, establishing the reductive half-reaction as rate-limiting at physiological pH. Deuteration of the lysyl Nε-methyl groups (H3K4me2-d6) produced identical kinetic isotope effects of 3.2 ± 0.1 on the kred, kcat, and kcat/Km values for the peptide, thus establishing C2H bond cleavage as rate-limiting with this substrate. The D(kcat/Km) value for the peptide was pH-independent, suggesting that the observed value is the intrinsic deuterium kinetic isotope effect for oxidation of this substrate.146 No intermediates between oxidized and reduced flavin forms were detected by stopped-flow spectroscopy, consistent with the expectation for a direct hydride transfer catalytic mechanism for amine oxidation. Additionally, the kcat/Km value for the peptide was bell-shaped, consistent with a requirement that the nitrogen at the site of oxidation be uncharged and that at least one of the other lysyl residues be charged for catalysis.144,145,147

A subsequent theoretical investigation by Karasulu and coworkers has confirmed that the H3K4me2 residue of the substrate has to be deprotonated in order for catalysis to occur, with K661 of KDM1A acting as the proton acceptor in the active site.148 Additional support for a direct hydride transfer mechanism was obtained through inhibition studies with tranylcypromine (2-PCPA, Parnate, 1).118,127 Parnate, which covalently inactivates KDM1A and KDM1B, is known to inactivate FAD-dependent enzymes that function through either the SET149 or direct hydride transfer mechanisms.150,151

As a further point of clarification, in KDM1A, reoxidation of the FAD cofactor by O2 is a relatively fast process compared to the turnover number measured under steady-state conditions.152 This entails that reoxidation is not the rate-limiting step of the chemical mechanism. Additionally, the FAD reoxidation rate is not perturbed by the presence of the product peptide152 and suggests that KDM1A can remain bound to the demethylated product and possibly functions through a ternary complex kinetic mechanism.153 Using computational approaches, Baron and coworkers suggest that molecular O2 diffuses though the enzyme for the purpose of reoxidaton while the demethylated product remains bound.123 Despite this prediction, there is no chemical requirement for the demethylated product to remain bound to the enzyme (i.e. the apparent rate of reoxidation is not faster or slower in the presence of the peptide product). Therefore, KDM1A might also function through a ‘ping-pong’ or double displacement kinetic mechanism, in which the release of the demethylated product occurs before reoxidation. Interestingly, in cell culture KDM1A removes a single methyl mark from p53-K370me2 to produce K370me1; however, in vitro it completely demethylates this residue.154,155 Thus, one may argue that the release of the demethylated product may be influenced by coregulatory molecules or other contributing factors capable of tuning its catalytic proficiency or substrate specificity.

Using classical molecular dynamics (MD) and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) approaches, Karasulu and coworkers provided theoretical support for a hydride transfer mechanistic pathway for methyl lysine oxidation over SET, carbanion, or polar-nucleophilic mechanisms.148 Proper alignment of the substrate, transitionstate stabilization (due to the protein environment and favorable orbital interactions), and product stabilization via adduct formation were found to be crucial for facilitating the oxidative C–H bond cleavage.148 Similarly, Truhlar and coworkers provided theoretical support for a hydride transfer mechanism, but also noted that because of the magnitude of the calculated free energy, a mechanism involving concerted transfer of a hydrogen atom and an electron could not be ruled out.156 Lastly, Kong and coworkers used theoretical calculations to provide support for a hydride transfer mechanism, but also used MD to implicate a conserved Y761 and K661-water-flavin motif in orienting FAD with respect to the substrate.157 Collectively, these theoretical analyses are in good agreement with the experimentally determined hydride transfer mechanism for KDM1A.148,156,157

KDM1B Chemical Mechanism

Tentatively, we suspect that KDM1B also adopts a similar hydride transfer chemical mechanism given the overall structural homology it maintains with the AOD of KDM1A, the conservation of active site residues, and subsequent, nearly identical, substrate specificity towards peptide substrates in vitro.14 Additional support for this hypothesis is reflected by the similar pH-rate profile behavior of the kinetic parameters as compared to KDM1A, non-covalent nature of the FAD cofactor, and highly similar catalytic efficiency parameters, with KDM1B being slightly less efficient in vitro.14,134–136

Chemical Mechanism Implications

When comparing KDM1A and KDM1B to other amine oxidases, it is important to note that the rate constant of substrate amine oxidation is 2–5 orders of magnitude slower than that of the MAOs and PAOs.158–164 This suggests that KDM1s likely evolved for substrate specificity rather than catalytic proficiency. Given the physiological role of KDM1 demethylases in the regulation of gene expression, high catalytic efficiency, which is necessary for metabolic enzymes to maintain balance among metabolic pathways, would be much less critical than very high specificity.

SUBSTRATE SPECIFICITY

Specificity for Histone Substrates

Shi and coworkers first reported that KDM1A was capable of demethylating methyllysine peptides derived from the highly conserved N-terminus of histone H3, as well as full-length H3 in vitro.13 No cross-reactivity for polyamine substrates was observed, despite the similarity of KDM1A to the PAO superfamily.13 They also reported that KDM1A is specific for histone H3K4me1/2, as no other methyllysine sites were processed.13 Forneris and coworkers demonstrated that histone H3 tail peptides greater than 16 aa in length are necessary to achieve demethylase efficiency in vitro. Additionally, they revealed that KDM1A demethylated H3K4me1 and H3K4me2 with similar kinetic parameters in vitro, illustrating a lack of a strong kinetic preference for either substrate.147

Mattevi and coworkers have also examined the contribution of residues within the H3 N-terminal tail to the efficiency of KDM1A demethylase activity, as well as the effects of epigenetic PTMs within this sequence.144,147,152 For example, Mattevi showed that methylation of H3K9 does not affect enzyme catalysis, yet acetylation at H3K9 increases the Km 6-fold for H3 peptide substrates methylated on K4. Similarly, phosphorylation of H3S9 abolishes demethylase activity, suggesting that KDM1A ‘reads’ PTMs along the histone tail.147,152 It was also proposed that electrostatic interactions likely contribute significantly to substrate binding, since demethylation activity was shown to be sensitive to ionic strength as well as hyperacetylation in vitro.147,152 Additionally, Mattevi showed that unmethylated H3-derived product peptides exhibit inhibition, which may serve to regulate KDM1A activity or localization.147 Parallel experiments conducted with KDM1B revealed a similar substrate specificity profile,14 which was anticipated given the significant active site structural similarity shared between the two enzymes in the AOD.112,134,136

While the ability of both KDM1A and KDM1B to demethylate H3K4me1/2 is quite striking, both enzymes do not demethylate H3K9me1/2 peptides in vitro.13,14,147 Despite lacking this activity towards peptide substrates, it has been suggested that KDM1A association with AR shifts its substrate specificity to H3K9me1/2 demethylation.84 However, the mechanisms behind these observations are not yet clear. A simple explanation is that AR association with KDM1A physically occludes its access to H3K4 or triggers recruitment of another demethylase, such as the H3K9me2/3-specific KDM4C (JMJD2C) demethylase.165 Alternatively, modifications on surrounding histone residues,166 a conformational change induced by a protein-protein interaction, or a PTM to KDM1A could potentiate this switch in specificity.167

As a member of the flavin-dependent oxidases, the KDM1 demethylases exhibit a strict requirement for proper substrate positioning in relation to the FAD cofactor to promote catalysis.129 However, KDM1s differ from other amine oxidases because their active sites are significantly expanded in order to accommodate the N-terminal residues of the histone H3 peptide (i.e. 1,245 Å3 in KDM1A).112 Within KDM1A, for example, there are four major invaginations lined with distinct groupings of residues to form complimentary interactions with H3 substrate side chains as well as for recognition of PTMs.111 No structural features within the active site of either enzyme have been found that might suggest that the methylation state of H3K4 can be distinguished sterically or electronically, and discrimination against H3K4me3 substrates is due to the inherent chemical mechanism of the enzymes.111,134 Although more than 16 N-terminal residues of H3 are required for efficient catalysis, a significant portion of the C-terminus of substrates likely extends from the active site and potentially interact along a cleft formed at the interface of the AOD and SWIRM domain.111,112,115,141 Mutations of residues in this cleft in KDM1A abolish or abrogate demethylation activity, suggesting that interactions with substrates within this region may provide an additional specificity determinant.111 Additionally, surface plasmon resonance interaction studies have demonstrated that the SWIRM domain of KDM1A interacts with H3-derived peptides.132 In KDM1B, the surface landscape of this region is quite different and binds the coregulatory protein Nuclear Protein 60kDa/Glyoxylate Reductase 1 Homolog (NPAC/GLYR1).135,136

In order to dissect the molecular basis of KDM1A and KDM1B substrate specificity, several three-dimensional structures have been determined of enzyme-substrate like complexes where short peptides occupy the active site in two general conformations (Figure 2).116,117,123,134–136 The structure of KDM1A bound to a substrate-like peptide inhibitor containing a N-methylpropargyl derivatized lysine residue at position four revealed density for residues 1–7 of the peptide and adopted an unusually compacted backbone with three consecutive γ-turns (Figure 2a).116 Subsequently, a H3 peptide inhibitor containing a K4M mutation (H3K4M, pK4M) was co-crystallized with KDM1A and CoREST,117 which revealed density for the first 16 residues of the peptide with the first five adopting an α-helical conformation (Figure 2b). It is important to note that the C-termini of each of these peptides points in opposing directions upon exiting the active site. Additionally, the N-terminal region of SNAI1 and related peptide derivatives have been co-crystallized with KDM1A and display a nearly identical conformation to that of the H3K4M peptide (Figure 2c), thus suggesting some form of molecular mimicry in KDM1A inhibition (Figure 2e).123,124 Finally, when KDM1B was co-crystallized in the presence of the same H3K4M peptide, it exhibited a similar binding conformation to that found in KDM1A (Figure 2d).134–136 Interestingly, elucidation of the structure of KDM1B bound to the cofactor NPAC/GLYR1 revealed a secondary binding site occupied by the C-terminal region of the H3 peptide tail.135

FIGURE 2.

Overview of structural conformations of bound peptide ligands. (a) Conformation of covalently bound N-methypropargyl-Lys4 H3 peptide in KDM1A (PDB 2UXN). (b) Conformation of non-covalently bound H3K4M (pK4M) in KDM1A (PDB 2V1D). (c) Conformation of non-covalently bound SNAI1 in KDM1A (PDB 2Y48). (d) Conformation of non-covalently bound pK4M in KDM1B (PDB 4HSU). (e) Structural alignment of pK4M and SNAI1 (b and c, respectively) bound to KDM1A, illustrating the overall fold conservation of the peptides and relative position of the non-covalent FAD and active-site Lys661.

Due to the above conformational differences and identification of the folate binding site within the KDM1A active site, there is some controversy as to which binding mode positions the K4 residue in the proper geometry that allows catalysis to proceed.4,117,126,167 Despite this discrepancy, both conformations reveal that the N-terminus of the peptides bind in an anionic pocket with a maximum of three residues N-terminal to the methyllysine residue.4,141 Additionally, both conformations make extensive contacts with a large set of conserved, negatively charged residues in the active site cavity.116,117 Overall, these structures exemplify the apparent plasticity of the active sites of KDM1A and KDM1B and only hint at the richness of substrate specificity mechanisms available to this enzyme class. Based on these data, it is speculated that KDM1A and KDM1B can recognize and demethylate different substrates in vastly different binding modes.4

Specificity for Non-Histone Substrates

In addition to histone H3, non-histone proteins have been shown to be substrates for KDM1 family enzymes. KDM1A has been shown to demethylate p53, DNMT1, E2F1, MYPT1, STAT3, HIV Tat, HSP90, MTA1, and potentially ERα (Table I).103,154,155,168–174 To our knowledge, no non-histone substrates have yet been identified for KDM1B; however, we suspect that future work will also define multiple, albeit different substrates and roles for this enzyme. The existence of multiple non-histone substrates for KDM1A has strong implications in apoptosis, cell cycle progression, and the transcriptional activation or repression of associated genes.

Table I.

KDM1 Demethylase Family

| Name | Synonyms | Histone Substrates | Non-Histone Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| KDM1A | LSD1, AOF2, BHC110, KIAA0601 | H3K4me1/2, H3K9me1/2 | p53 (K370), DNMT1 (K1096),a E2F1 (K185), ERα (K266),b HIV Tat (K51), HSP90 (K615h/K614m),c,d MTA1 (K532), MYPT1 (K442), STAT3 (K140) |

| KDM1B | LSD2, AOF1, C6orf193 | H3K4me1/2 |

Not verified to be major site of demethylation.

Inferred site of demethylation, not confirmed.

Confirmed in vitro.

Numbering system conventions between H. sapiens (K615h) and M. musculus (K614m).

The first non-histone substrate of KDM1A identified was the tumor-suppressor p53.154,155 Like histone proteins, p53 is subject to regulation by various PTMs. In particular, dimethylation of p53 at K370 (K370me2) promotes its association with 53BP1 (p53-binding protein 1), a protein that coactivates p53 transcriptional programs.175–177 Although in vitro KDM1A completely removes dimethylation at K370, in cell culture it preferentially removes a single methylation mark, generating the monomethylated species. This mark abrogates transcription through modulating p53-DNA interactions that subsequently repress the pro-apoptotic functions of p53. Further complicating this interaction, Barton and coworkers observed that KDM1A localizes only to genes where p53 represses transcription.154 This suggests some type of inherent regulation of the KDM1A-p53 interaction and may ensure repression of desired target genes.178

In contrast, in p53-deficient tumors, Set7/9 and KDM1A regulate DNA damage-induced cell death in a manner opposite to that observed in p53+/+ cells, via modulation of the stability of the transcription factor E2F1.169 Kontaki and Talianidis illustrated that Set7/9 methylates E2F1 at K185 and prevents E2F1 accumulation during DNA damage and subsequent activation of its pro-apototic target gene, p73. This PTM is removed by KDM1A, and is required for E2F1 stabilization and downstream pro-apoptotic function. Interestingly, the molecular mechanism of these events involves crosstalk between lysine methylation and other PTMs that affect E2F1 stability and turnover.

Recently, Sakane and coworkers have identified KDM1A as a HIV Tat K51me1-specific demethylase that is required for the activation of HIV transcription in latently infected T cells.103 The RNA-binding domain of Tat is a known region containing PTMs179 in which K51 is methylated by Set7/9.180 This PTM corresponds to an early event in the Tat transactivation cycle and strengthens the interaction of Tat with TAR RNA.180 On the other hand, acetylation of K50 is mediated by p300/ KAT3B, which dissociates the complex formed by Tat, TAR RNA, and the cyclin T1 subunit of the positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb).181,182 Subsequent to K50 acetylation, the histone acetyltransferase, PCAF/KAT2B, is recruited to the elongating RNA polymerase II complex.183–185 Interestingly, the association of the KDM1A/CoREST complex with the HIV promoter subsequently activated Tat transcriptional activity in a K51-dependent manner. In accordance with Tat transcriptional activity, shRNAs directed at KDM1A or its inhibition by phenelzine suppressed the activation of HIV transcription in latently infected cells. The study again illustrates the dual nature of KDM1A and its ability to function as both a transcriptional suppressor and activator depending on the context of the substrate and interacting partners.

In addition to p53 and E2F1, Chen and coworkers have identified DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) as a novel substrate of KDM1A.168 Targeted deletion of the gene encoding KDM1A (aof2) in mouse embryonic stem cells induces the progressive loss of DNA methylation in addition to an increase in the methylation of DNMT1 and a decrease in the DNMT1 protein level. Chen and coworkers illustrated that Set7/9 methylation of K1096 of DNMT1 can be reversed by KDM1A in vitro. Despite this evidence, it remains to be determined if K1096 is the major targeted site of KDM1A, since DNMT1 is methylated on multiple sites in vivo. By acting on and demethylating DNMT1, KDM1A may play a role in the coordination of DNA and histone methylation.

In another example, like E2F1, the transcription factor STAT3 is subject to PTMs that modulate downstream events in response to different cytokines and growth factors.186 Following phosphorylation, STAT3 is methylated on K140 by SET7/9 and subsequently demethylated by KDM1A when it is bound to a subset of promoters that it activates.171 Timing for this process occurs in an ordered sequence on the SOC3 promoter, illustrating the underlying temporal and spatial control of the methylation and demethylation events. The authors conclude that lysine methylation of promoter-bound STAT3 leads to biologically important downregulation of the dependent responses. This work illustrates the ability of methyltransferases and demethylases to control the methylation status of a transcription factor in a promoter-specific manner and provide a way to modulate the time of residence and promoter occupancy of the protein. Additionally, the transcription factors or the proteins recruited during these events may also provide a docking site for other proteins to carry out important functions, a role suggested for KDM1A by Mattevi and coworkers.152

Myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 (MYPT1) is an example of a KDM1A non-histone substrate that has a downstream affect on cell cycle progression.170 MYPT1, a known regulator of phosphorylation of the transcription factor retinoblastoma protein 1 (RB1), is methylated in vitro and in cell culture by SET7/9 and subsequently demethylated by KDM1A, in which K442 is the target residue. The methylation status of MYPT1 influences the affinity the protein maintains for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and subsequent protein turnover. Interestingly, overexpression of KDM1A, which is prevalent in many cancer subtypes (see above), could activate RB1 phosphorylation by inducing a destabilization of the MYPT1 protein. Subsequently, the release of E2F could activate transcription of genes required for S phase to enhance cell cycle progression.

An extremely unique target of KDM1A is metastatic tumor antigen 1 (MTA1), a core subunit of the NURD complex (discussed in detail later). Interestingly, it is the only known dual function coregulator with an expected corepressor activity, but unusual ability to also stimulate transcription.187,188 MTA1 is mono-methylated at residue K532 by G9a (EHMT2) and demethylated by KDM1A.173 This demethylation event is required for the stable interaction of the two proteins (i.e. KDM1A and MTA1), but also represents a molecular switch, as the methylation state of MTA1 potentiates the nucleation of either the NuRD or NURF complexes. Reconstitution of either complex occurs in a cyclical manner that alternates between opposing biological functions. This activity further compounds the role of KDM1A as both a transcriptional activator and repressor via the demethylation of a non-histone substrates and modulation of subsequent downstream targets.

The least well characterized KDM1A non-histone substrates are HSP90 and ERα.172,174 Using proteomics and biochemical approaches, Abu-Farha and colleagues determined that HSP90 is methylated at K209 and K615 by SMYD2,172 the latter of which is present in the dimerization domain (DD) of HSP90. Coincidentally HOP, a co-chaperone known to interact with the DD,189 blocks methylation at K615 in vitro. Although demethylation at this residue was performed in vitro by KDM1A, it has not yet been demonstrated in vivo. Furthermore, the methylation status of K615 has been implicated in the ability of HSP90 to associate with the sarcomeric protein titin, thereby affecting the maintenance and function of skeletal muscle.190,191 The role of HSP90 methylation status may also have potential, yet undiscovered, significance in carcinoma maintenance.192,193 On the other hand, the direct demethylation of ERα at K266 by KDM1A has not been explicitly demonstrated. However, KDM1A seems to negatively regulate the methylation status at this residue.174 It is interesting to suspect that the presence of KDM1A on estrogen responsive elements (EREs) has a dual role in the demethylation of H3K9me2 and ERα,194 or possibly uses this interaction to recruit an H3K9-selective demethylase enzyme to perform this function.

Interestingly, either SMYD2 (KMT3C) or SET7/9 (KMT7) methylates all but one of the current non-histone substrates that have been identified for KDM1A. In the future it will be informative to investigate more non-histone substrates of KDM1A and KDM1B to determine if they too maintain this same relationship with specific MTases. Such analyses may provide insight into the interplay between ‘writers’ and ‘erasers’ of PTMs in vivo.

INHIBITION OF FLAVIN-DEPENDENT KDM1 DEMETHYLASES

Discovery and Optimization of Mechanism-Based Inhibitors

The discovery and development of KDM1 family inhibitors has been the subject of several recent comprehensive reviews; therefore, an abbreviated overview of KDM1 inhibitors is presented, which includes many recent developments.15,21,69,142,195–199 Motivated by the relationship between the AOD of KDM1A to that of MAO-A/B and PAO, the first KDM1A inhibitors were discovered by McCafferty and coworkers.200 Through screening a focused group of irreversible and reversible amine oxidase inhibitors, tranylcypromine (trans– 2-phenylcyclopropylamine, 2-PCPA, Parnate™, 1) was found to exhibit the highest KDM1A inhibitory activity towards methylated bulk histones as well as methylated nucleosomal substrates in vitro. Treatment of P19 embryonal carcinoma cells with 1 resulted in the global increase of H3K4 methylation as well as transcriptional derepression of two KDM1A target genes, Egr1 and the pluripotent stem cell marker Oct4. This was the first example of small molecule inhibition of histone demethylation and interruption of transcriptional programs regulated by KDM1A.200

In a subsequent study, our group determined that tranylcypromine was a mechanism-based inactivator of KDM1A, forming a covalent adduct with the FAD cofactor and demonstrating inactivation kinetic parameters of KI = 242 µM and a kinact = 0.0106 s−1.127 Soon after, the laboratories of Cole,118 Yokohama,119,122 and Mattevi121 provided additional support for this inhibitory mechanism, including defining the structure of the tranylcypromine-KDM1A adduct using X-ray methods, which revealed the N5 of the FAD isoalloxazine ring as the site of covalent attachment of the inhibitor.

In addition to tranylcypromine (1), our study revealed less potent KDM1A inhibition from the hydrazine-containing phenelzine (2) and the propargylamines, represented by pargyline (3) and clorgyline (4) (Figure 3).200 KDM1A inhibitors 1 and 2 achieved complete inhibition in vitro at significantly lower concentrations than are physiologically relevant.127,201 However, propargylamines were not inhibitory at 5 mM, and only partial inhibition of KDM1A was observed at 30 mM.147,200,201 Exposure of cells to such non-physiologically relevant concentrations of 3 causes inhibition of proliferation and alteration of transcriptional programs via mechanisms that do not necessarily involve KDM1A activity.72 As such, one should approach the use of members of this inhibitor class with caution when attempting to attribute phenotypic effects exclusively to KDM1A inhibition.

FIGURE 3.

Chemical structures of representative mechanism-based, irreversible inhibitors.

Analysis of the crystal structures of KDM1A, MAOs, and PAOs, lead our group to conclude that KDM1A may be distinguished from related amine oxidases since MAO-A/B and PAO have significantly restricted active site volume when compared to KDM1A. As such, we designed, synthesized, and characterized analogues of 1 for the purpose of increasing potency and specificity towards KDM1A through aromatic substitutions and heteroaromatic exchanges.202 Within this initial group of inhibitors, improved selectivity and potency was observed, and these analogues were subsequently utilized to probe the role of KDM1A activity in estrogen receptor signaling.72 Since that time, numerous research groups, in addition to our own, have further optimized the potency and selectivity of arylcyclopropylamines for KDM1A inhibition.121,122,196,203–205

In fact, several members of the arylcyclopropylamine inhibitor class have achieved pre-clinical and clinical development status industrially. For example, Oryzon researchers reported the discovery of KDM1A inhibitor 5 that exhibited a 100-fold improved potency over the parent inhibitor 1. In a recent review, it was reported that Oryzon optimized 5 to produce ORY-1001 (structure not yet released), which possesses 1000-fold greater potency than 1 and is highly selective for KDM1A over KDM1B, MAO-A/B, IL4I1, and SMOX (SMO/PAO/PAO-1/PAOH1).198 Additionally, GlaxoSmithKline recently reported the discovery, development, and optimization of arylcycloproylamine-based KDM1A inhibitors (lead compound, 6) that achieve exclusive selectivity for KDM1A and also exhibit good oral bioavailability.206

Peptide-Based Inhibitors

Protein-protein and protein-ligand interactions provide auspicious starting points for the development of high affinity peptide and peptidomimetic inhibitors. Although this class of molecules has traditionally suffered from poor stability and cell permeability, modifications to the native peptide structure can greatly increase their pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic value. This inhibition strategy is especially appealing in regard to KDM1A, as it is involved in multiprotein complexes, several of which are beginning to be biophysically characterized in detail (see below). Here we outline the existing peptide-based active site inhibitors of the KDM1 class demethylases with the hope that they will catalyze the development of peptide-based inhibitors that target a wider range of KDM1 interfaces.

In addition to the small molecules discussed above, unmethylated product peptides (7) of the KDM1A reaction as well as a related substrate-like inhibitor containing a methionine point mutant (8; H3K4M; pK4M) have been shown to be competitive inhibitors of KDM1A with enhanced binding over methylated substrates.117,147 Recently, Kumarasignhe and Woster have also developed a series of cyclic peptides based on the substrate-like inhibitor pK4M that were more hydrolytically stable than the acyclic analogues. Additionally, moderate antitumor effects were observed in MCF7 and Calu-6 cancer cell lines.207 On the other hand, Mattevi and coworkers have developed a series of short peptide reversible inhibitors based on the N-terminal region of SNAI1, some of which exhibited anti-proliferative activity.123,124 Both classes of peptides show promise and may serve to lay the foundation for the development of peptidomimetic small molecule inhibitors.

In addition to reversible peptide inhibitors, several groups have also adopted an inhibitor design strategy whereby flavin-reactive moieties are grafted as ‘warheads’ onto peptides derived from histone H3, including reactive N-propargyl, -cyclopropyl, -aziridine, -phenelzine, -vinylchloride, or -tranylcypromine substituents (compounds 9–17; Figure 4).201,208,209 Within this series, phenelzine-containing H3K4-derived peptide (15) exhibited the most potent inhibitory activity in vitro;201 however, none of these compounds exhibited significant KDM1A inhibitor activity in cellular models, presumably due to poor cellular uptake or susceptibility to proteolytic degradation.210 Additionally, although alone pargyline is a very poor inhibitor of KDM1A,147,200,201 presentation of the propargylamine group as a pendant substituent within a peptide derived from histone H3 (9, 10) significantly enhanced its activity as a mechanism-based inactivator (Figure 4).116,201,208

FIGURE 4.

Structures of substrate-based peptide inhibitors.

Emerging KDM1A Inhibitor Classes

Recently, Jung and coworkers have reported the development of lysine mimetics that possess a propargyl warhead for covalent modification of KDM1A (18,19; Figure 5).211 Although these compounds were inhibitory at low micromolar concentrations, they did not exhibit selectivity over the MAOs and PAO in this first generation series. This class of molecules may likely gain selectivity through future optimization efforts.

FIGURE 5.

Structures of nonpeptidic, warhead small molecule inhibitors that are substrate derived mimics.

Similarly, Suzuki and coworkers have reported a series of KDM1A inactivators in which tranylcypromine (1) is coupled to a lysine carrier moiety at the nitrogen atom (20; Figure 5).212,213 The nonpeptidic small molecules selectively and efficiently delivered 1 to the KDM1A active site creating the inactivated, FAD-adduct in a time-dependent manner. Additionally, the molecules exhibited potent cell growth inhibitory activities against cancer cell lines. Together, the high potency and selectivity towards KDM1A allows this class of molecules to be considered good candidates for further optimization and implementation as chemical biology probes.

The considerable homology KDM1A shares with PAOs, including spermine oxidase (SMOX/SMO/PAO/PAO-1/ PAOH1) and others, spurred Woster and Casero to develop a class of reversible KDM1A antagonists capable of derepressing tumor suppressor genes, as well as inducing other beneficial anticancer activities. The first class of polyamine analogues contained bisguanide and bisguanidine functional groups (21, 22) that inhibited KDM1A activity in cell and animal models of cancer.214–216 Since that time, they have expanded the KDM1A inhibitor repertoire to also include (bis)urea and (bis)thiourea analogues (23–25) that have exhibited excellent potency, cell permeability, and selectivity for KDM1A inhibition.217 In a recent example,66 the polyamine (1,15-bis(N5-[3,3-(diphenyl)propyl]-N1-biguanido)–4,12-diazapentadecane) (22; Figure 6) induced cytotoxicity and inhibited KDM1A activity in human AML cell lines. Exposure to this agent increased global levels of H3K4me1/2 and exhibited reexpression of the tumor suppressor E-cadherin.

FIGURE 6.

Structures of bisguanide and bisguanidine polyamine inhibitors.

Polyamine analogues have enormous potential as therapeutics for many classes of human cancers, including breast, prostate, and AML. Also, there is potential for these molecules as probes for understanding the contribution of KDM1A to specific epigenetic demethylation events that contribute to cancer pathobiology. As such, the discovery and development of polyamine analogues as reversible KDM1A inhibitors has been the subject of several recent seminal reviews.19,197,218–222

Merging key pharmacophoric features of reported KDM1A inhibitors, Dulla and coworkers recently reported the development of 3-amino/guanidine substituted phenyl oxazole-containing inhibitors.223 Following treatment of cultured cells with nanomolar inhibitor concentrations, viability decreased as compared to the low micromolar range observed for inhibition of KDM1A in vitro. Although the basis of the enhanced reactivity in cell culture and the degree of KDM1A selectivity remains to be fully explored, one inhibitor (26; Figure 7) avoided zebra-fish embryo apoptosis and toxicity and may constitute a lead for further optimization. Additionally, it remains to be determined if this class is selective for KDM1A since these compounds were designed based on existing broad spectrum amine oxidase inhibitors.

FIGURE 7.

Structures of bifunctional small molecule inhibitors that incorporate multiple pharmacaphores.

Other examples of bifunctional KDM1A inhibitors have also recently been described. First, Zheng and coworkers reported a novel triazole-dithiocarbamate scaffold that inhibits KDM1A more potently than 1.54 The 1,2,3-triazole moiety within these inhibitors is readily accessible through the Cu(I)-catalyzed Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azides with alkynes (i.e. Sharpless “click” chemistry).224,225 Additionally, this pharmacophore has been shown to possess numerous biological activities,226,227 including inhibitory activity towards MAO-A.228,229 On the other hand, the dithiocarbamate pharmacophore was chosen for its intrinsic inhibitory activity against fungi, bacteria, and malignant cancer.230–232 One compound synthesized in the series (27; Figure 7) effectively reduced tumor growth of human gastric cancer cells in vivo.

In another example, Rotili and coworkers synthesized hybrid KDM1A/JmjC bifunctional inhibitors. This was achieved by coupling the skeleton of the KDM1A inhibitor tranylcypromine (1), with 4-carboxy-4’-carbomethoxy-2,2’-bipyridine or 5-carboxy-8-hydroxyquinoline chelating groups that were developed as competitive inhibitors for the iron(II)/ α-KG-dependent JmjC demethylases.86 Two compounds in this series (28,29; Figure 7) increase H3K4 and H3K9 methylation levels in cells and cause growth arrest and substantial apoptosis in LNCaP prostate and HCT116 colon cancer cells.86

Fortuitously, Yang and coworkers decided to test natural polyphenols as potential inhibitors of KDM1A.233 Dietary polyphenols are known to have beneficial effects against diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease, and exposure has been linked to both antioxidant activity and modulation of signaling pathways.234–236 Yang and coworkers demonstrated that resveratrol (30), curcumin (31), and quercetin (32) displayed inhibitory activity against KDM1A in vitro, which was independent of their antioxidant proproperties (Figure 8). However, since quercetin forms colloid-like aggregates in aqueous solution it may inhibit KDM1A in vitro non-specifically due to aggregate formation.237 Based on this precedence, further insight into its mode of action as well as structurally-related compounds is needed.

FIGURE 8.

Natural polyphenol inhibitors.

Screening has also been a means for identifying novel scaffolds against KDM1A and KDM1B and has yielded several anti-KDM1A inhibitor candidates. By combining protein structure similarity clustering and in vitro compound screening, Beuttner and coworkers discovered the KDM1A inhibitory activity of the γ-pyrone, Namoline, in vivo and in vitro (33, Figure 9).85 The IC50 of this compound was reported to be 51 µM against KDM1A and was fully reversible. Namoline administration to prostate cancer cells led to silencing of AR-regulated gene expression and impairment of androgen-dependent proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Namoline may be a promising starting point (i.e. core structure) for the development of therapeutics to treat androgen-dependent prostate cancer.

FIGURE 9.

Structures of screen identified and validated inhibitors.

On the other hand, Sharma and coworkers recently reported a structure-based virtual screen of a compound library containing ~2 million small molecules against KDM1A.238 Computational docking and scoring followed by biochemical screening led to the identification of a novel N’-(1-phenylethylidene)-benzohydrazide series of inhibitors. Hit-to-lead optimization and structure-activity relationship studies aided the discovery of a specific, reversible inhibitor (34) of KDM1A with a reported Ki of 31 nM. Compound 34 inhibits proliferation and survival in breast and colorectal cancer cell lines.

Zha and coworkers have also garnered recent success with a pharmacophore-based virtual screening approach to identify novel inhibitors of KDM1A.239 Using a moderate database of a commercial compound library and molecular docking tools, the group was able to identify nine candidate KDM1A inhibitors that lacked structural similarity to previously identified inhibitor classes. These compounds were subsequently tested in vitro against KDM1A and showed IC50 values in the low micromolar range. One compound, XZ09 (35), which showed the highest potency against KDM1A, was also tested versus MAO-A/B and showed moderate selectivity. The XZ09 core structure represents a lead compound that, with further modification, could serve as another tool in probing KDM1A function.

Finally, Cole and coworkers recently reported the design, synthesis, and characterization of the KDM1A inhibitory properties of phenelzine analogues.240 Bizine (36; Figure 10), a novel phenylzine analogue containing a phenyl-butyrylamide appendage, exhibited good in vitro activity against KDM1A (KI = 0.06 µM; kinact = 0.15 min−1; kinact/KI = 2.5 µM−1min−1) and was selective versus MAO-A/B (26- and 60-fold, respectively) and KDM1B (>100-fold). Bizine exhibited anti-proliferative effects in some cancer cells and was found to be effective at modulating bulk histone methylation. Additionally, these compounds synergistically inhibited cellular proliferation in combination with several histone deacetylase inhibitors. Interestingly, neurons exposed to oxidative stress were protected by the presence of bizine.

FIGURE 10.

Structures of mechanism-based phenelzine analogs.

FUNCTIONALLY IMPORTANT INTERACTIONS OF KDM1A AND KDM1B DEMETHYLASES WITH BIOMOLECULES

KDM1 family demethylases typically operate as catalytic subunits within specific stable complexes formed with additional biomolecules and enzymes that perform coregulatory or scaffolding functions. Such interactions link the catalytic activity of KDM1s to distinctive biological occupations, and have been shown to influence the degree of catalytic activity, substrate specificity, and/or localization of these enzymes within chromatin.

Interaction of KDM1A with CoREST and CoREST-like Proteins in Heteromeric Complexes

CoREST is one of the earliest identified interaction partners of KDM1A and this protein complex assembly (i.e. KDM1A/ CoREST complex) is frequently found within several distinct, larger multi-protein complexes.8,9,34,241–243 Most likely due to this early association, the structural and functional characterization of this particular interaction far outstrips that available for any other KDM1A interaction. CoREST consists of an N-terminal ELM2 domain followed by dual SANT domains (SANT1 and SANT2) with an intervening region colloquially known as the linker domain (Figure 11f). The N-terminal region spanning the ELM2 domain and first SANT domain have been mapped as a binding region for HDAC1,8 and a crystal structure of HDAC1 bound to a similar ELM2/SANT region in the CoREST-related protein, MTA1, has recently been reported.244 Furthermore, Shi and colleagues first mapped the interaction of KDM1A to the CoREST linker domain,34 indicating that CoREST likely acts as a scaffolding protein that joins deactylase and demethylase activity into a single catalytic sub-complex. The CoREST SANT2 domain, and possibly the SANT1 domain, has been shown to facilitate demethylation of nucleosomes, presumably by acting as a bridge between KDM1A and its substrate.34,115,242 A similar mechanism is observed in the SMRT protein, where the C-terminal SANT2 domain stabilizes the protein complex on chromatin by interacting with histone tails.245 As a point of further clarification, Yang and coworkers highlighted the similarity between the SANT2 domains of CoREST and the viral DNA-binding protein v-Myb, and demonstrated that an isolated CoREST SANT2 domain binds directly to DNA with modest affinity (Kd = 84 µM).115

FIGURE 11.

KDM1A complexes that utilize CoREST and CoREST-like interactions. (a) Ribbon representation of KDM1A (blue) in complex with the linker (orange) and SANT2 (yellow) domains of CoREST (PDB 2IW5). Insert highlights the regions of contact between CoREST and the KDM1A tower domain. (b) CoREST recruits a KDM1A complex to suppress neuronal genes through its interaction with REST, which also recruits the Sin3 complex. (c) The CoREST core complex is recruited by a direct interaction between TLX and KDM1A. This complex forms a negative feedback loop with the microRNA miR-137. (d) The transcription factor TAL1 recruits the CoREST complex, and potentially other coregulators, to repress gene transcription as an effector of hematopoietic differentiation. (e) The CtBP proteins associate with DNA-binding proteins for genomic localization and recruit chromatin remodelers, including KDM1A, to regulate the EMT. (f) Domain maps of CoREST and MTA1 are representative of their respective isoforms and show a similar ELM2/SANT domain organization. g) KDM1A is recruited by its tower domain to the MTA subunit of the NuRD complex, and in this context suppresses the EMT in breast cancer.

Seeking more detailed molecular characterization, Yang and colleagues reported the first crystal structure of KDM1A in complex with the linker and SANT2 domains of CoREST in 2006 (Figure 11a).115 In this model, the CoREST linker domain forms an L-shaped helical conformation, with the short helix contacting the base of the KDM1A tower domain, the longer helix extending up the TaB helix, and the SANT2 domain contacting the top turn of the tower (Figure 11a, insert). These interactions are mainly hydrophobic in nature, although a few electrostatic interactions may facilitate proper alignment of the CoREST linker with the KDM1A tower domain.115,130 A second crystal structure of KDM1A and CoREST with a histone substrate-like peptide bound (pK4M) showed little overall conformational change as compared to the non-peptide-bound structure.117 However, the model does illustrate that the L-shaped short arm formed by the CoREST linker may have an indirect effect on substrate binding by stabilizing the helix formed from KDM1A residues 372–395.

As noted above, although the CoREST SANT2 domain contacts the KDM1A tower in reported crystal structures,115,117 McCafferty and coworkers have demonstrated that the Co-REST linker domain is chiefly responsible for high affinity binding with KDM1A.130 Specifically, a CoREST fragment consisting of the linker domain (residues 293–380) exhibits low nanomolar binding affinity towards KDM1A (Kd = 7.78 nM), while inclusion of the SANT2 domain does not substantially alter binding affinity and in isolation lacks significant affinity towards KDM1A.130 Our group also used mutagenesis and isothermal titration calorimetry to reveal that the energy of binding along the CoREST/KDM1A helix-helix interface is not concentrated into “hotspots,” but is instead distributed almost uniformly along the interaction interface.246 As CoREST is required for nucleosomal demethylation,34,242 this argues that inhibitors of the CoREST linker/KDM1A tower interaction may inhibit KDM1A functionality in the cell.

In addition, MD studies by Baron and colleagues have suggested that the KDM1A/CoREST interaction may be dynamic. Specifically, their simulations indicate that the KDM1A SWIRM and CoREST SANT2 domains oscillate in distance and rotational angle in relation to each other, and that substrate binding allosterically rigidifies this fluctuation, favoring an “open” state.247–249 They further suggest that blocking these ‘hinge sites’ may prevent KDM1A/CoREST association with chromatin or other protein partners and therefore provide another potential strategy for modulating KDM1A function.250

In addition to the regulatory mechanisms enforced on KDM1A by CoREST, two CoREST paralogs, CoREST2 (RCOR2, 523 aa) and CoREST3 (RCOR3, four isoforms of 436, 449, 495, and 553 aa), have recently been revealed as further governors of KDM1A activity.251,252 These paralogs share a similar domain organization, including conserved ELM2 and dual SANT domains. Not surprisingly, CoREST2 and Co-REST3 both interact with KDM1A and are capable of incorporation into larger protein complexes.251,252 Similarly, the crystal structure of KDM1A bound to the linker-SANT2 domain of CoREST3 (residues 273–405; PDB 4CZZ) exhibited a nearly identical conformation as the KDM1A/CoREST (residues 308–440) complex (PDB 2V1D).251 However, CoREST2 displays a reduced ability to facilitate KDM1A nucleosomal demethylation252 and transcriptional repression as compared to CoREST.251 This weakening of repressive activity is attributed to residue L165 in the CoREST2 SANT1 domain, which diminishes its affinity for HDACs 1 and 2.251 However, CoR-EST3 plays an even more antagonistic role, as it competitively inhibits KDM1A nucleosomal demethylation. A CoREST3 chimera with the SANT2 domain replaced by the corresponding domain in CoREST reverses this phenotype and reinstates KDM1A nucleosomal demethylation.252 Collectively, these studies clearly indicate that CoREST and its paralogs play important roles in a subset of KDM1A-dependent transcriptional regulatory events by acting as a scaffold for the assembly and recruitment of deacetylase/demethylase-containing complexes, and by serving as a bridge to link epigenetic enzymes to nucleosomal substrates.

REST Complex

RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST) is a supervisor of cell fate decisions during neuronal differentiation, and functions as a transcription repressor that localizes to RE1 motifs in the promoters of neuron-specific genes (Figure 11b).253 In multipotent progenitor cells, these genes are held in a ‘primed-repressed’ state, in which REST recruits corepressor complexes mSin3254 and CoREST255–257 to its N- and C-terminal repressor domains, respectively, while simultaneously maintaining an activating chromatin environment and basal-level gene transcription.258 Upon differentiation into a neuron cell, REST is largely degraded to activate a neuronal expression program, although the CoREST complex sustains a role in tempering the expression of certain genes.258 Alternately, upon differentiation into a non-neuronal cell type, the REST/mSin3/ CoREST repressor machinery persists on RE1-containing promoters and adjusts chromatin in the vicinity of neuron-specific genes to a repressive state.258 Specifically, H3K4 demethylation is executed by KDM1A,13 and H3K9 methylation is likely mediated by the histone methyltransferases (HMTs) G9a and EHMT1, which are bridged to REST by the corepressor protein CDYL.259 The HMTs SUV39H1 and SETDB1 have also been linked to the CoREST complex and may play a role in H3K9 methylation.257,260 Increased CpG methylation (mCpG) in RE1 motifs has also been observed in differentiated cells compared to embryonic stem cells,258 although the DNA methyltransferase responsible has not yet been identified.