Abstract

Aim

To employ the thermal neutron background that affects the patient during a traditional high-energy radiotherapy treatment for BNCT (Boron Neutron Capture Therapy) in order to enhance radiotherapy effectiveness.

Background

Conventional high-energy (15–25 MV) linear accelerators (LINACs) for radiotherapy produce fast secondary neutrons in the gantry with a mean energy of about 1 MeV due to (γ, n) reaction. This neutron flux, isotropically distributed, is considered as an unavoidable undesired dose during the treatment. Considering the moderating effect of human body, a thermal neutron fluence is localized in the tumour area: this neutron background could be employed for BNCT by previously administering 10B-Phenyl-Alanine (10BPA) to the patient.

Materials and methods

Monte Carlo simulations (MCNP4B-GN code) were performed to estimate the total amount of neutrons outside and inside human body during a traditional X-ray radiotherapy treatment.

Moreover, a simplified tissue equivalent anthropomorphic phantom was used together with bubble detectors for thermal and fast neutron to evaluate the moderation effect of human body.

Results

Simulation and experimental results confirm the thermal neutron background during radiotherapy of 1.55E07 cm−2 Gy−1.

The BNCT equivalent dose delivered at 4 cm depth in phantom is 1.5 mGy-eq/Gy, that is about 3 Gy-eq (4% of X-rays dose) for a 70 Gy IMRT treatment.

Conclusions

The thermal neutron component during a traditional high-energy radiotherapy treatment could produce a localized BNCT effect, with a localized therapeutic dose enhancement, corresponding to 4% or more of photon dose, following tumour characteristics. This BNCT additional dose could thus improve radiotherapy, acting as a localized radio-sensitizer.

Keywords: BNCT, e-LINAC, Photo-production, Neutron

1. Background

Present-day cancer treatments still require further improvements in order to obtain a better dose control to target volume, reducing the incidence of secondary radio-induced tumours. One of the main drawbacks when dealing with radiotherapy is the necessity to precisely select the cells to be treated, reducing the damage to the healthy ones.

Today the efficiency of newer radio-sensitizers, acting on tumour cells, is investigated in many tumour diseases to improve the radiotherapy efficacy, intended to enhance tumour cell killing while having much less effect on normal tissues.1 Considering that BNCT2 (Boron Neutron Capture Therapy) is a selective therapy, because the carrier transporting 10B is preferentially accumulated in tumour cells, in this paper the combined effect of high-energy X-rays radiotherapy coupled with BNCT is studied.

BNCT consists of a two-step procedure: firstly a 10B carrier (usually 10B-Phenyl-Alanine – 10BPA) is administered to the patient; this substance is mainly localized in tumour cells, due to their faster metabolism.3 Secondly the patient is irradiated with an intense thermal neutron fluence rate; because of the high cross section of 10B for thermal neutrons (3840 barns at 0.025 eV), a nuclear reaction takes place producing heavy fragments from 10B (7Li and 4He) that release their energy inside the cells.4

1.1. Photoneutron production in medical LINACs

During conventional radiotherapy using high-energy e-LINACs (energy higher than 15 MV) neutron production results from the interaction of high-energy photons with various nuclides present in LINACs gantry. The production is governed by Giant Dipole Resonance reaction (GDR), and neutrons are generated when the incident photon energy exceeds the GDR reaction threshold (6–20 MeV).6 The nuclear photon absorption cross section, as a function of photon energy E, is described by the Levinger and Bethe formula,7 in which cross section is proportional to the atomic number Z of the nuclide considered.

Depending on the atomic number Z of the target nucleus, it is thus possible to distinguish two main cases: GDR threshold energy8 (EGDR, Th) of about 7–8 MeV for high-Z materials (Z > 20, such as Pb, W, Cu, Fe) that compose LINACs head and collimators, and EGDR, Th of about 16–18 MeV for low-Z ones (Z < 20 such as P, Ca, O, C) that constitute human body. Moreover, resonance peaks are several times higher for high-Z elements respect to low-Z ones (e.g. 186W resonance peak is ≈400 mbarns, at 13.5 MeV; 12C resonance peak is ≈20 mbarns at 24 MeV), so photo-neutron production is more important for high-Z elements. As a matter of fact, in conventional medical LINACs, neutrons production is mainly localized in the accelerator's gantry: target, filters, primary and secondary collimators, as multileaf collimator (MLC) or lead blocks, used for the final shaping of the treatment field, are made by high-Z materials (W, Pb, Au). Only 10% of undesired neutrons are directly produced inside human body in the treatment zone.9, 10

2. Aim

In this work the possibility to employ the unavoidable thermal neutron background that affects the patient during a standard high-energy radiotherapy5 treatment for BNCT application is investigated. If 10BPA is previously administered, 10B, especially localized in neoplastic cells, undergoes fission after thermal neutron capture, thus inducing heavy damages to the DNA of the cancer cells themselves, with a specific selectivity. So, the additional BNCT equivalent dose, due to 10BPA administration to the patient, could enhance radiotherapy treatment effectiveness, acting as a localized radio-sensitizer.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Simulation method: Monte Carlo MCNP4B-GN code

Linear accelerators (LINACs) are the most commonly used devices for external beam radiation treatments. Apart from delivering X-rays to the region of interest for tumour treatment, high-energy (E > 15 MV) LINACs are the source of photoneutrons due to their inner structure, as explained in the section above, emitting neutrons isotropically from the LINAC head.

In this work Monte Carlo simulations11 were performed to estimate the total amount of neutrons outside and inside human body during a traditional X-ray radiotherapy treatment. A routine implemented in the MCNP4B code, the MCNP4B-GN code (NEA 1733), especially developed by INFN (National Institute of Nuclear Physics) of Turin, for (γ, n) reaction was used. Its principal aim is to simulate the sophisticated LINACs geometry and to treat the electromagnetic cascade, the photon and electron transport and the photoneutron production by GDR reaction inside e-LINACs gantry and their transport in matter. The technique used is based on the division of space into cells bounded by surfaces of the first and second order as plane, sphere or cylinder. To compile an input file, the definition of three-dimensional geometry, the density and chemical composition of materials that make up the cells, the physical quantities that are to be estimated (such as particle flux, mean energy deposed, absorbed dose), are required. The e-LINAC head simulated by the MCNP4B-GN code is represented in Fig. 1.

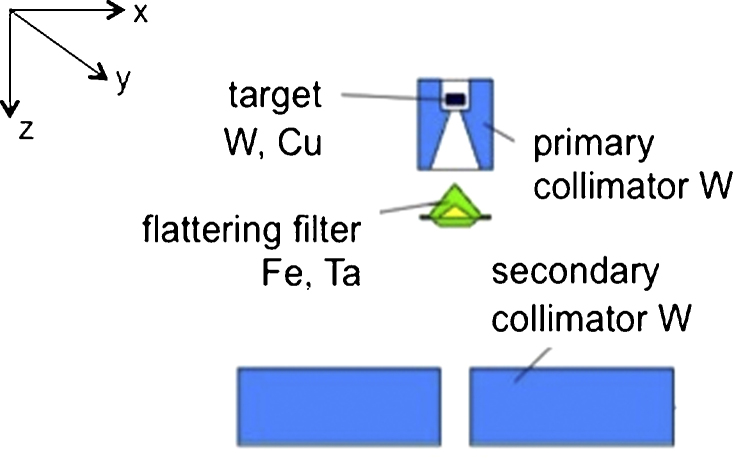

Fig. 1.

LINAC head simulated by MCNP4B-GN code. LINAC VARIAN 2300 CD 18 MV. Target (made up by tungsten and copper), flattering filter (iron and tantalum), primary and secondary collimators (tungsten), are represented. Section on plane y = 0. The origin of the reference system is placed in the centre of target and the z axis is directed downward, along the isocenter line.

In the simulation code, (γ, n) and (γ, 2n) channels are treated and both evaporative and direct models of neutron emission from the nucleus are considered. Since photonuclear cross-sections are more than 2 orders of magnitude lower than the main atomic processes (Photoelectric, Compton and Pair production), suitable and effective variance reduction techniques were applied.12, 13

From an operational point of view the e-LINAC beam parameter in standard conditions (SSD – source surface distance of 100 cm and photon field equal to 10 × 10 cm2) can be summarized as follow: 35 mA for electron current impinging on the target, 200 Hz for repetition rate (frequency electron pulse) and 2.4 μs for effective pulse duration. So the effective electron fluence rate on LINACs target is of the order of 1.0E14 e−/s. This value varies following the energy and technical characteristics of the accelerator, and is used as a normalization factor for the simulation results (expressed per a single source electron): the higher is the number of electrons striking on target, the higher is the number of X-rays produced by Bremsstrahlung and consequently the amount of neutrons produced by GDR reaction.

3.2. Experimental detection system

To evaluate the moderation effect of human body during a traditional radiotherapy treatment, a simplified tissue equivalent anthropomorphic phantom was used together with bubble detectors for thermal and fast neutron.

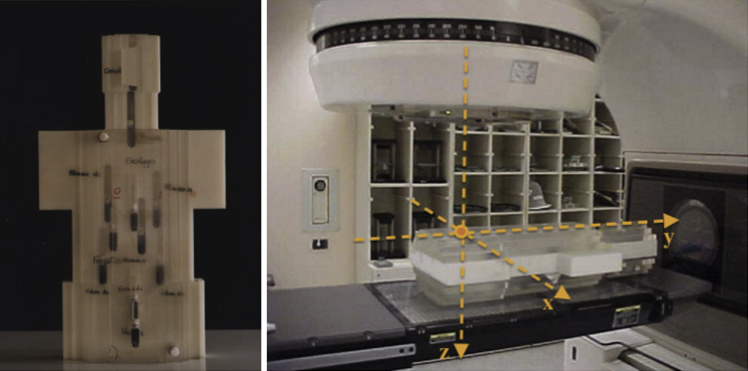

The phantom, Jimmy, was designed and made by INFN of Turin in collaboration with the Ispra JRC (Join Research Centre), Varese, Italy. It was especially developed for neutron dosimetry in order to evaluate the neutron spectrum and the neutron equivalent dose in tissue (NCRP 38).14 The phantom Jimmy is made up by different slabs of plexiglass and polyethylene, and has human bone dust inserted in correspondence of the vertebral column. There are also 16 cavities in correspondence of critical organs suitable to allocate integral passive bubble dosimeters (BTI – Bubble Tech. Ind., Ontario, Canada)15: BD-PND sensitive to fast neutrons (100 keV < E < 20 MeV) and/or BDT for thermal neutrons (E < 0.4 eV), in order to detect dose in depth (accuracy BTI: ±20%). Jimmy was designed following the International Commission on Radiological Protection indications for neutron dosimetric phantom both about organ positions (ICRP 60)16 and tissue substitutes (ICRU 44).17 The phantom external dimensions are: head (15 × 13.5 × 19 cm3); neck (10 × 11 × 13.5 cm3); body (59 × (30–36) × 20 cm3). The anthropomorphic phantom Jimmy and a typical experimental set-up are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Jimmy anthropomorphic phantom and the LINAC. The total structure, accelerator and Jimmy phantom, is considered in MCNP4B-GN simulation. Photon beam is centred on gonads position and isocenter is at 4 cm depth in phantom.

4. Results

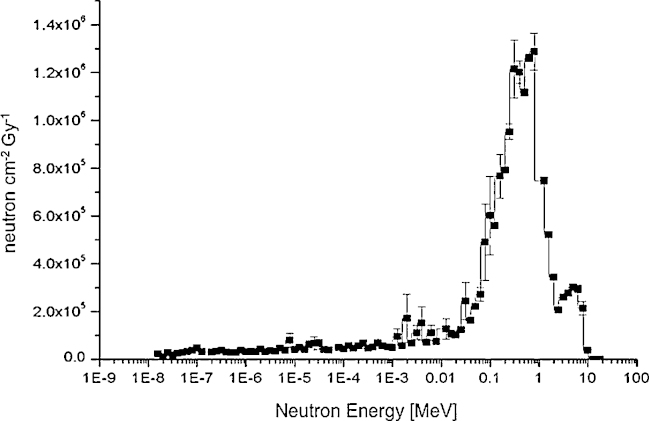

The typical photoneutron energy spectrum simulated using e-LINAC VARIAN 2300 CD 18 MV at patient plane in standard condition during a classical radiotherapy treatment is shown in Fig. 3. The mean neutron energy ranges between 700 keV and 1 MeV.18 The dominant energy peak centred around 1 MeV is due to evaporation mechanism, in which the neutron angular emission is isotropic, and the energy distribution follows the Maxwellian curve. Moreover a peak can be observed for energies higher than 3 MeV due to direct-reaction neutron knockout component: in this case the angular distribution is anisotropic, f(θ) = a + b(sin θ)2, and the energy distribution is given by the difference between the photon energy and the binding energy, En = Eγ – Eb.

Fig. 3.

Neutron fluence per Gy at the patient plane during a classical radiotherapy treatment. LINAC VARIAN 2300 CD 18 MV. SSD = 100 cm; photon field = 10 × 10 cm2; jaws 10 × 10; multileaf 40 × 40. Simulation carried out by MCNP4B-GN (NEA 1733) code at 3 cm from isocenter.

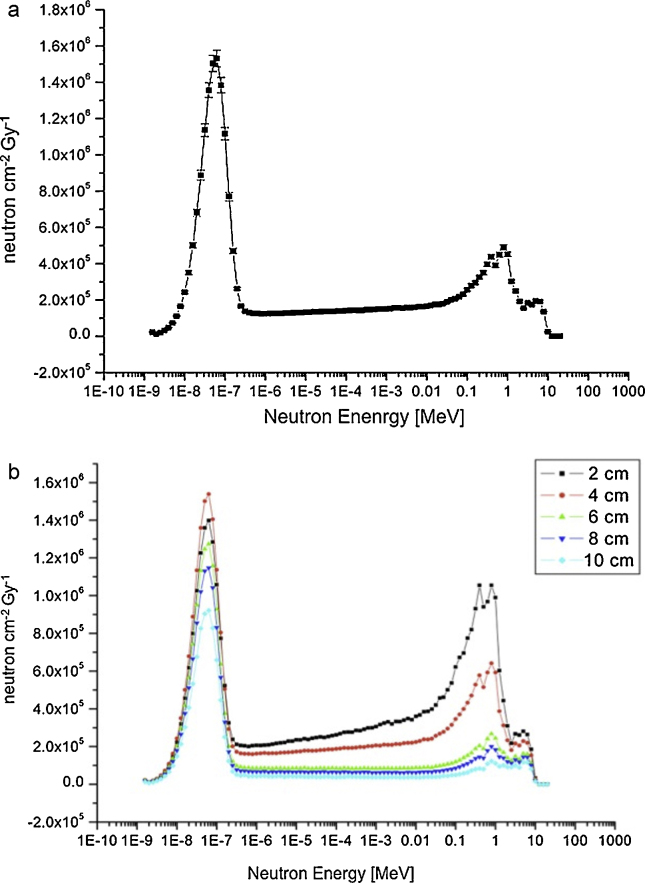

The anthropomorphic phantom Jimmy was implemented in the MCNP4B-GN input file at 100 cm from e-LINAC target, the photon beam centred on gonads position and isocenter at 4 cm depth in tissue. The photoneutron energy spectrum in standard condition inside the phantom is shown in Fig. 4a: an intense thermal neutron peak of about 1.55E07 n cm−2 Gy−1 arises in the lower energy range, inside the treatment zone, due to moderation of fast neutrons produced at the patient plane. It is also shown in Fig. 4b photoneutron spectra evaluated at different depth in phantom. The relative importance of thermal and fast neutron peaks change with the deepness in phantom.

Fig. 4.

(a) Average neutron fluence rate [n cm−2 Gy−1] at 4 cm depth in phantom, simulated by MCNP4B-GN. Notice the consistent thermal neutron peak in lower energy range. Irradiation in standard condition. (b) Neutron fluence per Gy at different depth in phantom simulated by MCNP4B-GN. Going deeper, fast neutron component is thermalized, while thermal component is then absorbed. In the configuration studied the most favourable depth is at 4 cm.

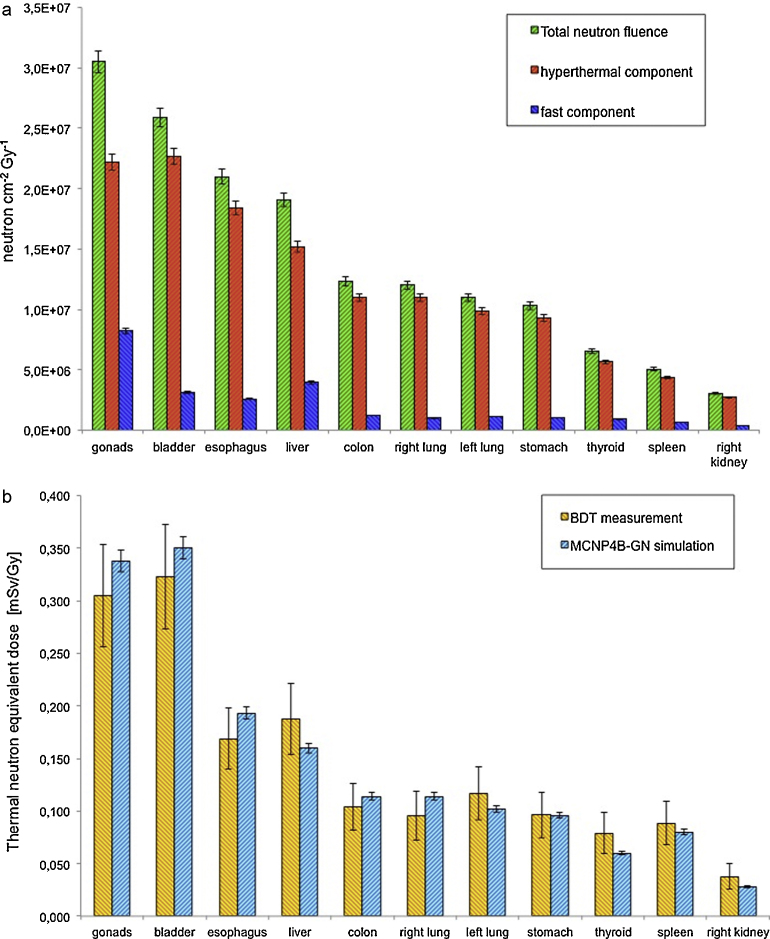

In Fig. 5a the neutron fluence per Gy in organs calculated by MCNP4B-GN simulations is shown for thermal and fast components, whereas in Fig. 5b the thermal neutron equivalent dose measured by BDT detectors compared with the correspondence simulation results is reported.

Fig. 5.

(a) Neutron fluence per Gy components in organs when the photon beam is centred on gonads position and isocenter at 4 cm depth in phantom. Irradiation in standard condition. MCNP4B-GN simulation result. Neutron fluence decreases moving away from gonads position and going deeper in phantom. (b) Thermal neutron equivalent dose at organs when the radiation source is centred on gonads position and isocenter at 4 cm depth in tissue. Irradiation in standard condition. Comparison between BDT measurement and MCNP4B-GN simulation results. Accuracy BDT: 20%.

To compare experimental and simulation results, neutron equivalent dose was studied starting from neutron fluence: conversion factors from fluence to dose (DT/Φ, expressed in pSv cm2) tabulated in NCRP 3814 were inserted in the MCNP4B-GN input file in order to calculate the absorbed dose DT in tissue.

The experimental set-up is that shown in Fig. 2, in which the photon beam is centred on gonads position and isocenter is at 4 cm depth in phantom; irradiation is in standard condition.

4.1. BNCT additional dose

To evaluate the additional dose due to BNCT it is necessary to take into account the various physical dose components, arising from neutrons and gamma interactions with biological tissues and 10B captured by cells. The total physical dose consists of the gamma dose (Dγ), due to gamma of 2.2 MeV from thermal neutron capture reactions on hydrogen in tissue; the fast neutron dose or hydrogen dose (DH), due to recoil protons from fast neutron reactions in tissue; the thermal neutron dose or nitrogen dose (DN), from thermal neutron reactions by nitrogen nuclei and the boron dose (DB), due to the neutron capture reactions by 10B that absorbs a thermal neutron. Eq. (1) gives the weighted biological dose (Dw), expressed in terms of photon-equivalent unit (Gy-eq), which the biological effects to be taken into account

| (1) |

where Dγ, DH, DN and DB are the physical dose components, and wγ, wn, wB are the weighting factors. The weighting factors values are, respectively, wγ = 1 for photons, wn = 3.2 for neutrons, wB = 1.3 for boron in healthy tissue and wB = 3.8 for boron in tumour19, 20; Dw is the weighted biological dose.

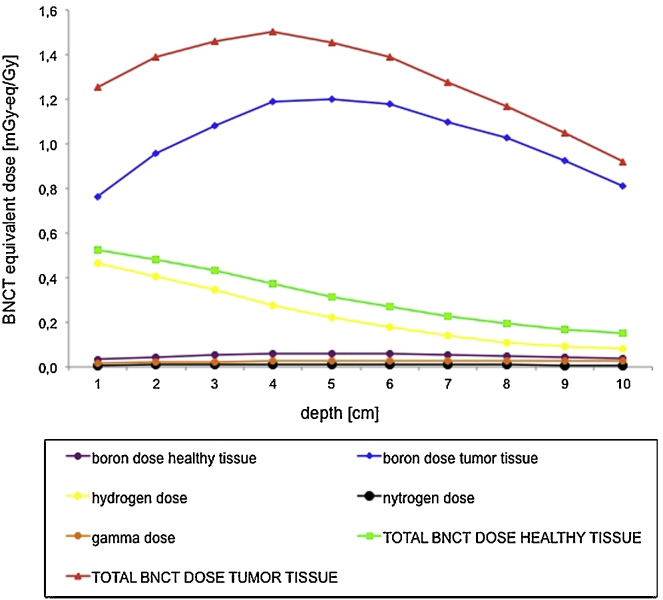

Using these parameters, and considering the phantom exposure as in Fig. 2, the BNCT equivalent dose profiles in depth and its physical components are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

BNCT equivalent dose profiles in depth and its different physical components calculated for a thermal neutron total fluence of 1.55E07 cm−2 Gy−1 and a healthy-to-tumour tissue ratio 1:6. It can be observed that the total BNCT dose to tumour tissue, red line, is mainly due to the boron dose, blue line. The total dose to healthy tissue, green line, is mainly due to the fast component, yellow line.

The BNCT dose delivered for 1 Gy of photon dose at 4 cm depth in phantom is about 1.5 mGy-eq/Gy, for a thermal neutron total fluence at treatment zone of 1.55E07 cm−2 per Gy and a healthy-to-tumour tissue ratio of 1:6.

In a conventional 70 Gy radiotherapy treatment, the BNCT additional dose is about 0.11 Gy-eq. This value depends on e-LINACs characteristics and energy, from the collimation system, and from different radiotherapy treatment protocols.

This contribution could considerably increase when the improvement in photon beam collimation requires a longer time to deliver a certain dose to target volume and also an accurate evaluation of the e-Linac Output Factor (OF).21 As a matter of fact, a greater number of Monitor Unit (MU), linked to OF, corresponds to a major neutron flux. For example, during a 70 Gy IMRT radiotherapy treatment (1815 MU with respect to 100 MU for traditional radiotherapy treatment), patients could undergo an additional BNCT dose component, localized inside tumour cells, of about 3 Gy-eq (i.e. 4% of the X-rays dose). This BNCT additional dose could thus improve radiotherapy, acting as a localized radio-sensitizer.

5. Conclusions

In this work the possibility to perform a coupled treatment with high-energy LINACs (15–18 MV) and BNCT is examined.

A patient undergoing a conventional radiotherapy treatment is always affected by an undesired neutron dose, which presents an intense thermal neutron fluence (1.55E07 n cm2 Gy−1) localized in the tumour zone. If a boron compound (10BPA) is previously administered to the patient, this neutron component could produce a localized BNCT effect, with a localized therapeutic dose enhancement, corresponding to 4% or more of photon dose, following tumour characteristics. This application is a preliminary study of the possibility to use undesirable neutron contamination for the enhancement radiotherapy treatments. In routine photon treatments the dose is usually delivered in many fractions, so the application of this study at present seems to be not possible in practice. However, it could be of interest in the future because of the new trend in radiotherapy, consisting of dose escalation and in dose hypo-fractioning, i.e. using a very high MU number per Gy (until 2000 MU/Gy) administering the total therapeutic dose in few sessions.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank the staff of Radiotherapy Department of Hospital Mauriziano in Turin and Hospital Maggiore in Trieste for technical help and useful discussions.

References

- 1.Candelaria M., Garcia-Arias A., Cetina L., Dueñas-Gonzalez A. Radiosensitizers in cervical cancer. Cisplatin and beyond. Radiat Oncol. 2006;1(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth R.F., Soloway A.H., Fairchild R.G. Boron neutron capture therapy for cancer. Sci Am. 1990;263(4):100–103. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1090-100. 106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borasio P., Giannini G., Ardissone F., Papotti M., Volante M., Fava C. A novel approach to the study of 10B uptake in human lung by ex-vivo BPA perfusion. 13th International Congress on Neutron Capture Therapy; Florence, Italy; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coderre J.A., Morris G.M. The radiation biology of boron neutron capture therapy. Radiat Res. 1999;151:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanini A., Diemoz P., Roberto E., Borla O., Durisi E. Atti del XXXIII Congresso AIRP. 2006. Dose indesiderata di fotoni e neutroni in trattamenti IMRT. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akkurt I., Adler J.R.M., Annand F., Hansen K., Ongaro C., Reiter A. Photoneutron yields from tungsten in the energy range of the GDR. Phys Med Biol. 2003;48:3345–3352. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/20/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levinger J.S., Bethe H.A. Dipole transition in nuclear photo effect. Phys Rev. 1950;78:115. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Photo-neutron cross sections at web site: http://t2.lanl.gov/nis/data/endf/endfvii-g.html

- 9.Ongaro C., Zanini A., Nastasi U., Rodenas J., Manfredotti C. Analysis of photoneutron spectra produced in medical accelerators. Phys Med Biol. 2000;4:L55–L61. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/12/101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanini A., Fasolo F., Ongaro C., Nilsson P., Nastasi U., Scielzo G. Patient plane and in tissue neutron spectra in photon radiotherapy treatments by Linac's. Proceedings of the Workshop on Neutron Spectrometry and Dosimetry: Experimental Techniques and MC calculations; Stockholm, 18–20 October 2001; 2004. pp. 225–235. [edited by Otto editore] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briemeister J.F. Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1997. MCNP, a general Monte Carlo N-particle transport code. Report LA-12625-M. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ongaro C., Zanini A., Nastasi U. Monte Carlo simulation of the photo-production in the high-Z components of radiotherapy linear accelerators. Monte Carlo Methods Appl. 1999;5:69. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burn KW, Ongaro C. Photoneutron production and dose evaluation in medical accelerators, ENEA report RT/2002/51/FIS.

- 14.NCRP (National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements) 1971. Protection against neutron radiation. Report 38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.1992. Bubble Technology Industries instruction manual for the bubble detector. Chalk River, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICRP (International Council on Radiological Protection) Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Ann ICRP. 1991;21(1–3) Publication 60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ICRU (International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements) 1989. Tissue substitutes in radiation dosimetry and measurements. Report 44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ongaro C., Zanini A., Nastasi U., Rodenas J., Ottaviano G., Manfredotti C. Analysis of photoneutron spectra produced in medical accelerators. Phys Med Biol. 2001;46(3):897. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/12/101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harling O., Riley K. Fission reactor neutron sources for neutron capture therapy – a critical review. Neuro-oncology. 2003;62:7–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02699930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burn K.W., Casalini L., Daffara C., Nava E., Petrovich C., Gualdrini G. Monduzzi Editore; 2001. Design of an Epithermal Facility for treating patients with brain gliomas at the TAPIRO fast reactor at ENEA Cassaccia. Research and development in neutron capture therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clifford Chao K.S. 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelfia: 2005. Practical essentials of intensity modulated radiation therapy. [Google Scholar]