Significance

The iconic great houses of Chaco Canyon occupy a nearly treeless landscape and yet were some of the largest pre-Columbian structures in North America. This incongruity has sparked persistent debate over the origins of more than 240,000 trees used in construction. We used tree-ring methods for determining timber origins for the first time to our knowledge in the southwestern United States and show that 70% of timbers likely originated over 75 km from Chaco. We found that a previously unrecognized timber source, the Zuni Mountains, supplied construction beams as early as the 850s in the Common Era. Further, we elucidate shifting dynamics of procurement that highlight the importance of a single landscape, the Chuska Mountains, in the florescence of the Chacoan system.

Keywords: Ancestral Puebloans, archaeology, human–environment interactions, dendrochronology, timber origins

Abstract

An enduring mystery from the great houses of Chaco Canyon is the origin of more than 240,000 construction timbers. We evaluate probable timber procurement areas for seven great houses by applying tree-ring width-based sourcing to a set of 170 timbers. To our knowledge, this is the first use of tree rings to assess timber origins in the southwestern United States. We found that the Chuska and Zuni Mountains (>75 km distant) were the most likely sources, accounting for 70% of timbers. Most notably, procurement areas changed through time. Before 1020 Common Era (CE) nearly all timbers originated from the Zunis (a previously unrecognized source), but by 1060 CE the Chuskas eclipsed the Zuni area in total wood imports. This shift occurred at the onset of Chaco florescence in the 11th century, a time with substantial expansion of existing great houses and the addition of seven new great houses in the Chaco Core area. It also coincides with the proliferation of Chuskan stone tools and pottery in the archaeological record of Chaco Canyon, further underscoring the link between land use and occupation in the Chuska area and the peak of great house construction. Our findings, based on the most temporally specific and replicated evidence of Chacoan resource procurement obtained to date, corroborate the long-standing but recently challenged interpretation that large numbers of timbers were harvested and transported from distant mountain ranges to build the great houses at Chaco Canyon.

The high desert landscape of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico was the locale of a remarkable cultural development of Ancestral Puebloan peoples, including the construction of some of the largest pre-Columbian buildings in North America (1) (Fig. 1). The monumental “great houses” of Chaco Canyon reflect an elaborate socioecological system that spanned much of the 12,000-km2 San Juan Basin from 850 to 1140 Common Era (CE) (2). These massive stone masonry structures required a wealth of resources to erect, including an estimated 240,000 trees incorporated as roof beams, door and window lintels, and other building elements (3). The incongruity of the great houses located in a nearly treeless landscape has led archaeologists and paleoecologists to investigate the origins of timbers used in construction (4–9). Beyond the simple curiosity driving this question, the answer has important implications for understanding the complexities of human–environmental interactions, the sociopolitical organization, and the economic structure of Chacoan society (10–12).

Fig. 1.

Aerial view of Pueblo Bonito, the largest of the Chaco Canyon great houses. Image courtesy of Adriel Heisey.

The first excavators of the great houses in the early 20th century speculated that construction timbers were harvested locally, perhaps resulting in deforestation of the surrounding landscape (13). Paleoecological studies conducted during the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, showed that ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), the primary tree species used in construction, was not abundant enough at the relatively low elevations (1,800–2,000 m above sea level) of Chaco Canyon and nearby mesas to support timber demand (14–16). Spruce (Picea spp.) and fir (Abies spp.), which account for tens of thousands of construction beams, have been absent from Chaco Canyon for at least 12,000 y and could have only been logged from distant, higher-elevation sites (2,500–3,450 m above sea level) (4). An inadequate supply of timbers in Chaco Canyon and its immediate surroundings during Puebloan occupation strongly suggests long-distance procurement from surrounding mountain ranges, where all three conifers now grow in abundance. This inference was corroborated by strontium isotope (87Sr/86Sr)-based sourcing. Through a comparison of 87Sr/86Sr values from great-house timbers to 87Sr/86Sr values from conifer stands growing today in mountains surrounding the San Juan Basin, two studies concluded that the Chuska Mountains (75 km west) and Mount Taylor (85 km southeast) were the most likely sources for spruce, fir, and ponderosa pine trees (6, 7). Recently, the explanation of long-distance timber transport and the related interpretations of 87Sr/86Sr evidence have been challenged and an alternative has been proposed that most great-house timbers (particularly ponderosa pine) were just as likely to have originated from nearby and low-elevation sites within, east, and south of Chaco Canyon (8, 9).

We assessed probable timber origins independently from previous efforts by applying tree-ring width-based sourcing techniques to a set of 170 beams from our archives at the University of Arizona. These beams comprise six tree species from seven great-house structures (Table S1). Tree-ring-based sourcing uses correlation and Student’s t tests between beams of unknown origin and site chronologies from likely timber harvesting areas (17) (Fig. S1). Each site chronology, as the average of 40–100 trees, represents tree-ring growth patterns peculiar to an individual landscape. This method of identifying the probable origin of timbers has been applied widely in Europe in the study of archaeological and nautical timbers and artifacts, musical instruments, and paintings on oak panels (17–20). These techniques are underused in North America, but recent efforts in the northeastern United States have revealed distant, inland sources for 18th- and 19th-century nautical timbers (21, 22).

Table S1.

Number of sourced beams by species and great-house structure

| Structure | Douglas-fir | Juniper | Piñon | Ponderosa pine | Spruce/fir | Total |

| Casa Chiquita | 1 | 1 (100) | ||||

| Chetro Ketl | 1 | 1 | 3 | 73 | 19 | 97 (18) |

| Kin Kletso | 2 | 2 (9) | ||||

| Peñasco Blanco | 5 | 5 (20) | ||||

| Pueblo Bonito | 3 | 1 | 3 | 27 | 2 | 36 (14) |

| Pueblo del Arroyo | 1 | 1 | 20 | 3 | 25 (13) | |

| Pueblo Pintado | 3 | 1 | 4 (31) | |||

| Total | 5 (4) | 3 (33) | 9 (13) | 129 (18) | 24 (18) | 170 (16) |

Values in parentheses provide the percent of the 1,048 available beams meeting our selection criteria.

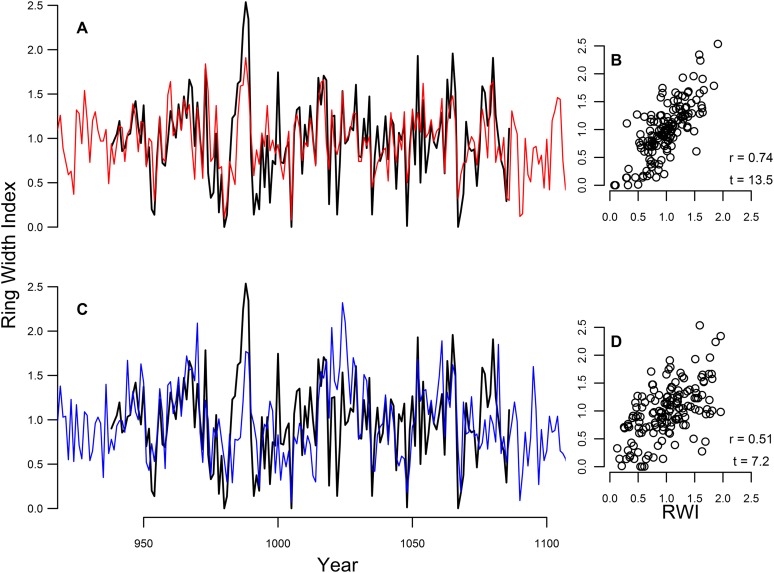

Fig. S1.

An example of sourcing a great-house beam via tree-ring-width methods. (A) An individual beam (black line), the ponderosa pine JPB-88 from Pueblo del Arroyo, and the Chuskas chronology (red line). (B) Bivariate plot comparing the ring-width indices of the beam with the source-area chronology. Correlation (r) and t values are provided. (C) The same beam (JPB-88) with the southern Jemez chronology (blue line). (D) As in B, but with JPB-88 and the S. Jemez chronology. In this case, the beam clearly matches better to the Chuska area.

Tree-ring sourcing can only be applied where tree growth patterns are distinguishable between the potential locations of origin. In the southwestern United States tree growth primarily responds to regionally coherent winter precipitation (23, 24), and as a consequence trees across the region tend to share roughly half of their interannual variability (25). Differences between site chronologies are predominantly attributed to variations in topography and subregional-scale climate conditions (26).

We compared great-house beams to the site chronologies of eight potential harvesting areas surrounding the San Juan Basin. Chaco Canyon was not included as one of our sites because it lacked enough remnant wood from the Chaco era to build a local site chronology. To assess the efficacy and accuracy of the tree-ring sourcing method within the San Juan Basin, we tested whether tree-ring growth patterns could be distinguished between the various mountain ranges surrounding Chaco Canyon by applying sourcing methods to living trees of known origin (SI Text and Table S2). We found that within the San Juan Basin, despite a broadly coherent climate–tree growth signal, the ring-width growth patterns in individual trees can be used to correctly identify the specific mountain range from which they came (Fig. S2).

Table S2.

Tree-ring sites used to evaluate tree-ring-based sourcing in the San Juan Basin

| Fig. S2 tile | Site name | Species* | No. of trees | Date range | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation, m above sea level | Contributor | ITRDB file† |

| A | Crystal | PIPO | 13 | 1652–1978 | 36.01 | −108.80 | 2,755 | Cleaveland | NM529 |

| B | Grand View Ridge | PIED | 20 | 1566–2002 | 37.13 | −107.51 | 2,012 | Woodhouse | CO638 |

| C | Cat Mesa | PIPO | 13 | 1572–1986 | 35.81 | −106.64 | 2,515 | Swetnam | NM556 |

| D | Satan Pass | PSME | 21 | 1381–1972 | 35.60 | −108.10 | 2,286 | Dean | NM025 |

| E | Burning Bridge Wash | PIED | 20 | 1629–1976 | 35.90 | −107.60 | 2,195 | Dean | NM053 |

| F | Chaco East | PIPO | 27 | 1372–1994 | 35.99 | −107.73 | 1,967 | Windes (46) |

Species: PIPO, P. ponderosa; PIED, P. edulis; PSME, P. menziesii.

Refers to the file name on the International Tree-Ring Data Bank (ITRDB), accessible at www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/paleoclimatology-data/datasets/tree-ring.

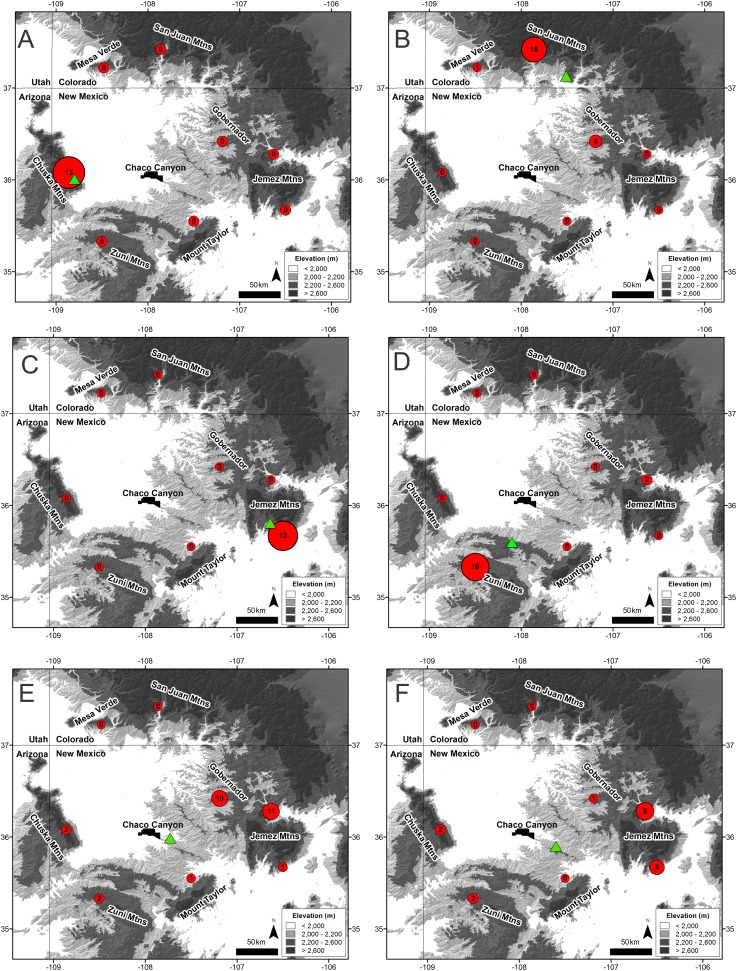

Fig. S2.

Evaluation of dendroprovenance in the San Juan Basin. (A–F) Each tile provides a different test for a set of modern trees (green triangles). Circle sizes are proportional to the number of trees (labeled in the circle) sourcing to a given location. Site information is provided in Table S2; a description of the test is presented in SI Text.

Results and Discussion

We defined the source of each of the 170 great-house timbers as the tree growth location with the highest significant Student’s t value (a combination of correlation and length of overlap, assessed at α = 0.01). It is worth noting that many beams had significant t values with multiple source areas, and tests of differences among these failed to separate the majority of them. Our use of maximum t values to designate probable origins is justified against the results of our evaluation of tree-ring sourcing in the San Juan Basin (SI Text and Fig. S2). The accuracy rate of this test is 90% across all four test sites but rises to 100% for the two test sites located within the same mountain range as a source-area chronology. Because the mountain ranges contain far more forest resources than the mesa locations of the other two test sites, it is plausible that much of the great-house construction wood came from areas represented by our eight source-area chronologies. Here, we describe a broad and compelling pattern of origins for great-house timbers that is both independent of and in accord with the sourcing of other Chacoan materials, including timbers.

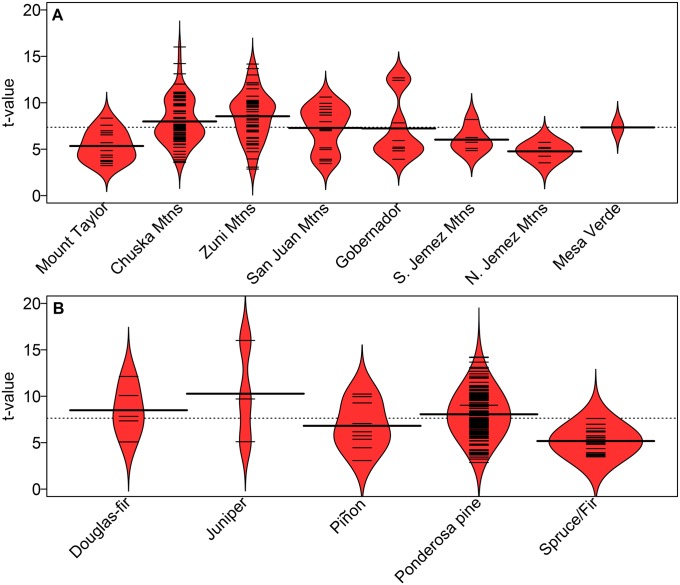

Maximum t values for tree-ring sourcing of beams ranged from 2.86 to 16.01, with 75% greater than 5.58 and only four beams below the often-used yet arbitrary threshold for significance of t = 3.5 (27) (Dataset S1). Average t values for the Chuska and Zuni Mountains were the highest (Fig. S3A). Differences in sourcing strength between species were negligible, although spruce and fir trees had the lowest mean t value (Fig. S3B). Using more conservative subsets of the sourcing results generated little change in our findings and no differences in interpretation (SI Text and Table S3).

Fig. S3.

Strength of sourcing by (A) probable location and (B) tree species. The t values for individual beams are shown as small dashes, and the long black lines give the mean of each category. The dotted lines provide the overall median t value in each graph. Polygons indicate the general spread of the t values as probability distributions. These are produced by a Gaussian kernel density function with a bandwidth equal to the average SD across all categories in each graph (48).

Table S3.

Comparison of sourcing results between conservative subsets of beams

| Location | ≥30 rings | ≥75 rings | t ≥ 6 | ≥75 rings and t ≥ 6 |

| Mesa Verde | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Northern Jemez Mountains | 6 (4) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Southern Jemez Mountains | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Gobernador | 8 (5) | 6 (5) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) |

| San Juan Mountains | 16 (9) | 12 (9) | 11 (9) | 9 (9) |

| Zuni Mountains | 48 (28) | 41 (31) | 39 (33) | 36 (37) |

| Chuska Mountains | 71 (42) | 53 (40) | 56 (48) | 43 (44) |

| Mount Taylor | 15 (9) | 11 (8) | 5 (4) | 4 (4) |

Shown are the number of beams sourcing to each location given the subset criteria, with the percent of beams meeting that criteria in parentheses.

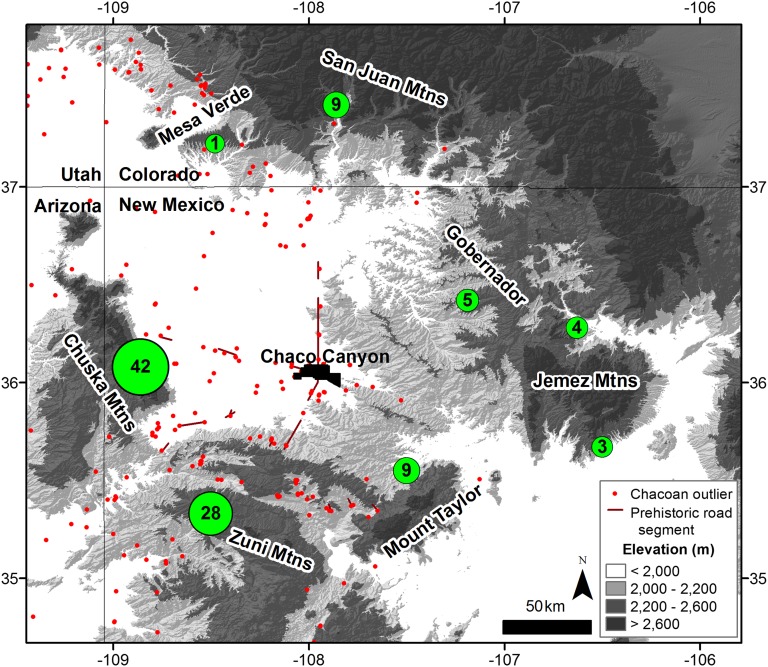

We found that 70% of the timbers most likely originated from the Chuska and Zuni Mountains, each >75 km from Chaco Canyon (Fig. 2). No other potential location accounted for more than 9% (n ≤ 16) of the beams, fewer than would be expected by chance (χ2 = 204, P < 0.001). Sourcing patterns differed somewhat by species (Fig. S4). In the case of ponderosa pine, the Chuskas accounted for 50% and the Zunis for 29%. The Zuni Mountains were also important for piñon (Pinus edulis) and juniper (Juniperus spp.) trees, accounting for 58%. Results for spruce and fir were similar to those of English et al. (6), with Mount Taylor as the primary source (29%).

Fig. 2.

Source locations for great-house timbers (n = 170). The sizes of the green dots are proportional to the percent of beams sourcing to that location; values provide the percentages. Locations of outlier sites and prehistoric road segments come from Mills et al. (43) and Kantner and Kintigh (44), respectively.

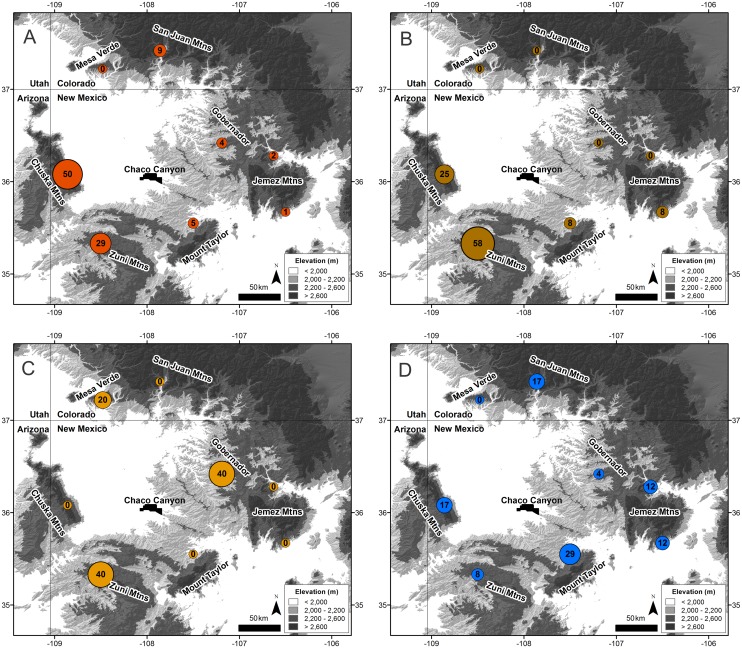

Fig. S4.

Sourcing results by tree species. Dot sizes are proportional to the percent of beams sourcing to that location; values provide the percentages. (A) Ponderosa pine, (B) piñon and juniper, (C) Douglas-fir, and (D) spruce and fir.

Our findings that identify the Chuska and Zuni Mountains as a significant source of great-house beams are consistent with previous interpretations of long-distance timber procurement (4–7, 10, 11). A pair of recent studies, however, challenge this idea based on similarities in the 87Sr/86Sr values for trees in the Chuska Mountains and soil in Chaco Canyon (8, 9). They conclude, therefore, that low-elevation sites within and near the Canyon were just as likely sources for ponderosa beams as were the Chuskas, despite a lack of ponderosa pine in the paleoenvironmental record of the Canyon and surrounding areas since ∼5,000 y ago (14–16, 28). If large numbers of local ponderosa pines were to exist in the canyon during the Chaco era and were used as construction timbers (8, 9), then we would expect the sourcing of the great-house beams to show a similar pattern to the “sourcing” of modern pines from low-elevation sites within Chaco Canyon (Fig. S2F). Modern (post-1300 CE) ponderosa pines growing in north-facing alcoves on the eastern end of the Chaco Core associate most strongly to the Jemez region on the eastern side of the San Juan Basin. The Chuska and Zuni Mountains, where the great-house timbers source, are instead to the west (Fig. 2), suggesting that it is unlikely that trees within or near Chaco Canyon were major sources of construction timbers.

Previously, the Zuni area had been identified as a logical procurement area for timber (11) and other resources (29, 30). Our study is the first to our knowledge to source great-house timbers to the Zuni Mountains. Owing to the general lack of large stands of spruce and fir in the present species composition of the mountain range, the area was not considered in the strontium sourcing studies (6, 7). Our results indicate that wood was imported from the Zunis as early as the 850s CE.

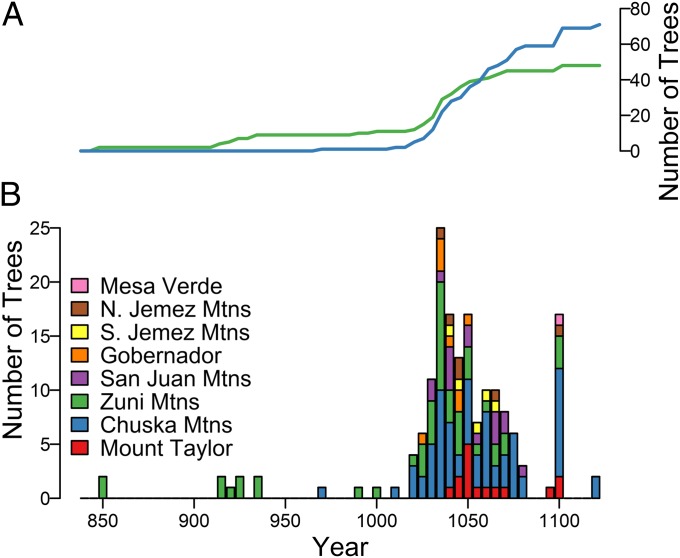

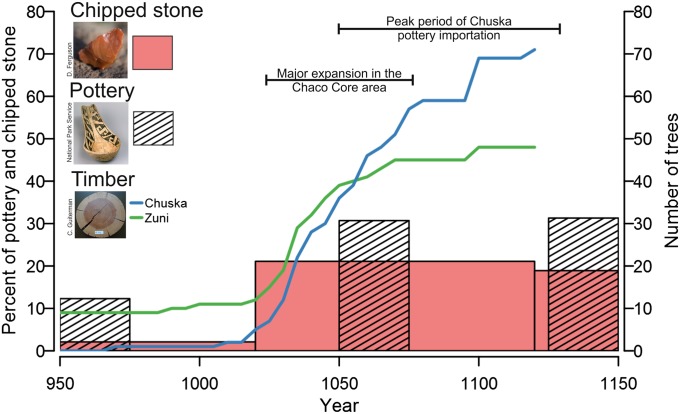

To evaluate changes in procurement areas through time we analyzed only beam specimens that have cutting or near-cutting outside dates spanning the temporal range of timber harvesting (Fig. S5). We found that before 1020 CE, nearly all beams sourced to the Zuni Mountains, and thereafter the Chuska Mountains, rose in importance, eclipsing the Zuni region by 1060 CE (Fig. 3 and Fig. S6). This apparent shift in timber procurement coincides with the proliferation of other Chuskan goods in the Chaco Canyon archaeological record (Fig. 4). After ca. 1020 CE, Narbona Pass Chert (unique to the Chuska Mountains) accounted for >20% of the chipped stone tool assemblage in Chaco (31). Correspondingly, Chuskan pottery, usually made with temper from Narbona Pass, was extensively imported after ca. 1040 CE (32, 33).

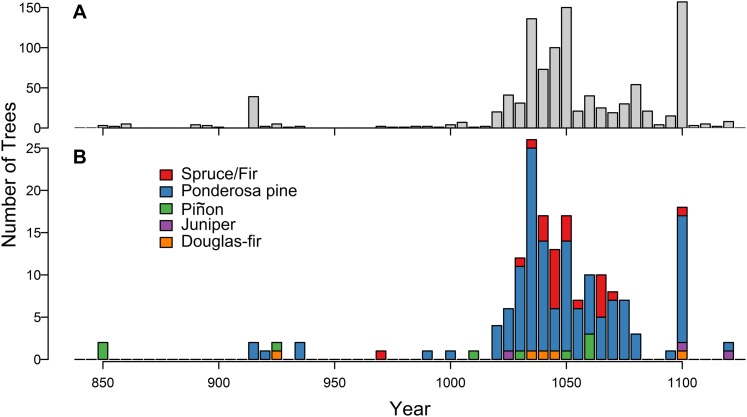

Fig. S5.

Temporal distribution of beams with cutting and near cutting outside dates. (A) All great-house timbers that met our four criteria described in the text. (B) Timbers we analyzed. Spruce and fir are grouped because we did not differentiate these genera.

Fig. 3.

Time series of great-house timber origins. Both plots are on the same time scale. (A) The cumulative sum of beams sourcing to the Zuni (green) and Chuska (blue) Mountains. (B) Distribution of cutting dates by 5-y bins for each source location. The bars are plotted on the center year of each bin.

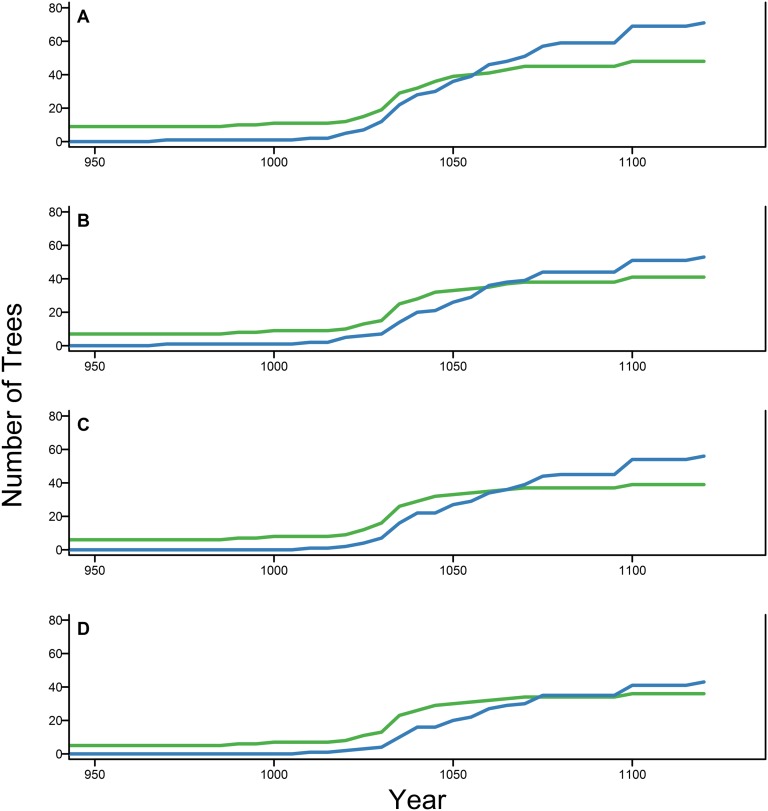

Fig. S6.

Comparison of more conservative subsets of great-house timbers. For each plot, the lines show the cumulative sum of source results for the Chuska Mountains (blue) and Zuni Mountains (green), as in Figs. 3 and 4. The above plots show consecutively more conservative subsets of our results. (A) the full dataset with series ≥30 rings as in the main text, (B) only series ≥75 rings, (C) only beams with t ≥ 6, and (D) beams that have ≥75 rings and t ≥ 6.

Fig. 4.

Time series of the Chaco great-house archaeological record. Percentages for chipped stone and pottery represent the amount of Narbona Pass Chert (31) and Chuskan pottery (1) in those records. Curves for construction timbers are the same as in Fig. 3A. Highlighted time periods for construction and importation of pottery come from the Chaco Synthesis Project (1).

At the same time the Chuska Mountains rose in importance during the middle 11th century CE, there was an onset of major architectural expansion in the Chaco Core area that is additionally defined by a change in masonry style (1). Expansion occurred at existing great houses (Pueblo Bonito, Peñasco Blanco, and Una Vida) and seven new great houses were built, comprising half of the great-house structures in the canyon. Whether this surge in construction and new design drove regional expansion of the Chaco system toward the Chuska Mountains or was in response to expansion in that area remains an open question. An explanation for the shift from mostly Zuni-area timbers in favor of Chuskan wood remains equally elusive but may relate to shorter travel distances between the Chuskas and Chaco that would have facilitated large-scale expansion in the Canyon, or a dwindling resource supply along the Zuni front after centuries of occupation. Improved dating and analyses of the Chaco outlier network, particularly on the eastern front of the Chuska Mountains, may provide answers to both questions (12).

The results of our study independently confirm the hypothesis that distant forested landscapes were the sources for hundreds of thousands of timbers used to build the great houses of Chaco Canyon. Our tree-ring-based results, in accordance with the strontium isotope studies, determine the Chuska Mountains as the primary procurement area. Our discovery of the Zuni Mountains as a source of timber has not only expanded the area from which beams are most likely to have been procured, but it also elucidates a temporal shift in timber procurement. The presence of a network of outlier sites and village clusters at the base of the Chuska and Zuni Mountains (Fig. 2) further supports our conclusions by suggesting a direct connection between these upland forests and the semiarid desert of the Chaco Core area. Given that our findings correspond with isotopic and archeological evidence of increasing use of the Chuskan landscape after 1020 CE (Fig. 4), a preponderance of evidence now indicates the importance of this particular landscape in the development and florescence of the Chacoan system.

The great houses of Chaco Canyon represent an enormous investment in materials, labor, and human ingenuity, requiring favorable environmental conditions and complex socioeconomic structures to construct and maintain. Although Chacoan exchange networks extended as far as Mesoamerica for prestige items (34, 35), the procurement of basic, labor-intensive resources from multiple distant landscapes, with shifting dynamics of use, is a prominent feature of Chacoan society. Testing for similar patterns at other pre-Columbian and historic sites in North America would be a fruitful endeavor and is possible now because of a dense network of long tree-ring chronologies and the rich collection of archaeological wood material housed at the University of Arizona and National Park Service archives.

Materials and Methods

San Juan Basin Tree-Ring Chronologies.

We used eight tree-ring chronologies in the San Juan Basin to represent the likely timber harvesting areas for Chaco Canyon great houses (Table 1 and Dataset S1). Each chronology is composed of one to four tree species, with greater numbers of species further back in time. In most cases, the chronologies are built from living tree samples dating back to ∼1300 CE, and then extended back in time with archaeological wood from individual sites or site clusters. We assume that beams from these upland archaeological sites represent locally harvested trees because of the abundance of suitable trees near the sites, which is not the case for Chaco Canyon.

Table 1.

Source-area chronologies from the San Juan Basin

| Location | Site code | Species* | Date range | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation, m above sea level | Source |

| Mesa Verde | MVER | 1 | 550–1989 | 37.22 | −108.48 | 2,263 | 41 |

| Northern Jemez Mountains | MEA/CDP | 1, 2, 3 | 620–2012 | 36.28 | −106.63 | 2,525 | 36, this study |

| Southern Jemez Mountains | JEM | 2, 4 | 598–1972 | 35.67 | −106.50 | 2,011 | 41 |

| Gobernador | GOB | 2 | 623–1989 | 36.42 | −107.19 | 2,230 | 41 |

| San Juan Mountains | DUR | 1, 4, 5 | −319–2009 | 37.42 | −107.86 | 2,213 | 41, 42 |

| Zuni Mountains | CIB | 1, 2, 4, 5 | 435–1972 | 35.33 | −108.50 | 2,072 | 41 |

| Chuska Mountains | CHU/NAR | 1, 2, 4, 6 | 532–2012 | 36.09 | −108.86 | 2,650 | 41, this study |

| Mount Taylor | CEB | 4 | 680–1986 | 35.55 | −107.50 | 2,072 | 41 |

Species: 1, P. menziesii; 2, P. ponderosa; 3, P. strobiformis; 4, P. edulis; 5, Pinus flexilis; 6, Juniperus spp.

One chronology (Mesa Alta) contains no archaeological specimens, with the pre-1600 period consisting of subfossil logs found on the landscape. For this site, we combined two chronologies composed of different species to boost the strength of the local tree-ring growth signal by adding sample depth during the Chaco period. One of these chronologies (MEA) is composed of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and southwestern white pine (Pinus strobiformis) (36), and the other (CDP) is ponderosa pine that we collected for this study. The Chuska Mountains chronology combines ponderosa pine and piñon subfossil wood from Narbona Pass (NPS) that we collected and archaeological wood excavated from 13th-century pueblos at the eastern foot of the mountain range (CHU). This combination was done to boost sample depth and increase the local common signal in the pre-1300s period, and to fill a time gap in our Narbona Pass chronology resulting from a lack of material dating between 1081 and 1140 CE.

Great-House Timbers.

We selected Chaco Canyon great-house specimens from the archaeological collections of the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona. To enable systematic selection from thousands of archived specimens, we first digitized the complete record of individual specimen catalog cards for the great houses. These data were assembled into a Microsoft Access database consisting of 6,421 records (the complete database is available from www.chacoarchive.org/cra/chaco-resources/tree-ring-database/). Of these, 2,497 beams have been assigned exact calendar dates. Our selection criteria for specimens to source consisted of conifers that had at least 30 measurable rings, were solid wood (i.e., not charcoal because of its fragility and associated difficulty to measure), came from a distribution of great houses, had cutting or near-cutting outside dates, and represented the temporal distribution of available specimens (Fig. S5). These criteria narrowed our available selection to 1,048 trees. This includes some duplicates where a single beam was sampled more than once by different excavators, resulting in more than one specimen ID or database record. In the process of measuring beams, we took care to avoid duplication by consulting laboratory technician notes, where this is often indicated. In selecting and measuring specimens, we gave preference to older trees, and thus more than 75% of our samples have more than 75 rings.

We measured ring widths to the nearest 0.001 mm on a Velmex system, recorded observations of injuries, ring anomalies, false rings, and frost rings, and photographed each sample. We used the COFECHA computer program (37) to assess the quality of measurements and crossdating (raw measurements are available in Dataset S1). Finally, biological growth trends of the measured beams were removed by division against 50-y cubic smoothing splines (38) in R using the dplR package (39, 40).

In all, we measured 174 specimens, but four were omitted from further analyses because they did not significantly match any of the San Juan Basin chronologies, leaving 170 beams in our final dataset of great-house timbers. These specimens include at least six tree species from seven great-house structures (Table S1). Because spruce and fir are difficult to differentiate (4) they have not historically been differentiated in the archaeological collection, nor has a systematic effort been made to differentiate Abies lasciocarpa from Abies concolor. Because of these uncertainties, and the relative consistency of spruce and fir as codominants in upper elevation forests, we grouped the two genera into a single category for analyses. We know, however, that our dataset contains both spruce and fir because seven of our beams were identified to their genus by scanning electron microscopy (4).

It is uncertain how well our sample of beams represents the population of great-house construction timbers, of which there were at least 240,000 harvested trees (3). The tree-ring archaeological record is limited to a very small portion of this total estimated population. Fewer than 10,000 beams have been excavated from the great houses, and dendrochronologists could date fewer than 2,500 of those (primarily because many lacked enough rings or adequate growth variability for confirmed dating). This record is all that is available for study, and we have therefore designed our test for origins on a sample of it. We chose a representative sample of the available record with respect to the component of cutting dates rather than other possible parameters or the population of timbers in its entirety. Although there is uncertainty about potential bias in our available sample, we would note that this problem is not unique to this study and exists in paleoecology and archaeology in general. Animal or plant specimens and artifacts that survive long times, are discovered, sampled, and effectively dated and analyzed are commonly a very small subset of a much a larger population of unknown statistical distribution. Nevertheless, useful and accurate interpretations and information are often obtained, especially when combined with testing and other, independent lines of evidence, as we have discussed in the present case. It is hoped that further sampling and dating work in the future, and perhaps new methods of analysis, will further test our interpretations.

Analyses.

Sourcing archaeological timbers consisted of performing correlation analyses between the measured beams and the eight San Juan Basin chronologies. Before calculating correlations, we removed autocorrelation from each series via autoregression modeling. Statistical significance of the correlations was assessed with one-tailed t tests (α = 0.01), whereby the correlation values (Pearson’s r) were converted to t values using

where n is the length of overlap between the two series (27). Any nonsignificant correlations were excluded from analysis. We assigned the origin of each beam to the location of the regional chronology with the highest significant t value.

To assess whether the number of trees sourcing to each location exceeded what might be expected by chance, we applied the χ2 goodness-of-fit test (chisq.test) in the R stats package.

SI Text

Evaluation of Tree-Ring Width-Based Sourcing in the San Juan Basin.

Following Daly (45), we tested whether tree-ring growth patterns were distinguishable among landscapes in the San Juan Basin to evaluate the effectiveness of tree-ring sourcing methods in the region. We hypothesized that trees from a given area will correlate most strongly with site chronologies from the same area. For the test, we used the eight chronologies described in the main text to represent each landscape (Table 1) and compared living trees of known origin to them to assess where the trees “source.” Data for the trees of known origin came from previously sampled sites in the San Juan Basin and are independent of the chronologies used for sourcing timbers (Table S2). We accessed tree-ring data for five of the six sites from the International Tree-Ring Databank; the sixth site, Chaco Canyon ponderosa pine (Chaco East), consists of wood collected by National Park Service personnel [described by Windes (46)] and archived at the University of Arizona. These trees are from a few scattered ponderosa pine stands found in some cooler/wetter alcoves and north-facing slopes in the eastern portion of Chaco Canyon.

Tree species included in the test sites are ponderosa pine (three sites), piñon (two sites), and Douglas-fir (one site). The two sites closest to Chaco Canyon (Burning Bridge piñon and Chaco East ponderosa) were included to provide a sense of where great-house timbers might source if they were harvested locally. This was done because we lack a Chaco Canyon chronology long enough to compare with great-house timbers. The first four test sites, therefore, represent trees growing in the upland areas most likely to have been used by Chacoans (Table S2).

For each test site, we used a single measurement series from each tree to mirror the methods we use on great-house timbers. All statistical treatments and procedures were identical to the beams, including the standardization, removal of autocorrelation, and calculation of Pearson product-moment correlations and t values. We chose the location of the highest t value as the “source” for the trees of known origin.

Results of these tests support the use of tree-ring based sourcing in the San Juan Basin (Fig. S2). For the four upland sites, 90% of the trees sourced to their known location (Fig. S2 A–D). For the Chuska Mountains and Jemez Mountains, all 13 trees at each site sourced correctly (Fig. S2 A and B). The Grand View Ridge piñon site was 75% accurate, with the other trees (n = 5) sourcing to the two nearest neighboring ranges (Fig. S2B). For the Satan Pass Douglas-fir site just north of the Zuni Mountains, all but two trees sourced to the Zunis, with the other two sourcing to Mesa Alta (Fig. S2D). This result could have been driven by differences in growth pattern among species, because both Satan Pass and Mesa Alta include Douglas-fir. These two sites (Grand View Ridge and Satan Pass) were not located in the same mountain range as the nearest source-area chronologies, which may have contributed to their lower rates of accuracy. If we include those trees that sourced to the nearest neighboring range, the overall accuracy rate was 97% (65 out of 67 trees).

The Chaco-area trees (Fig. S2 E and F) tend to source toward the east, with most trees (n = 38) matching best to the Jemez Mountains and Gobernador chronologies. In each test, only two trees sourced to the Zuni and Chuska Mountains. These results contrast those of the great-house timbers, which mostly sourced to the Chuskas and Zunis, supporting the general interpretation that locally grown, Chaco-area trees were unlikely to have been a major source of great-house timbers.

Evaluation of More Conservative Beam Subsets.

The length of overlap between an individual beam and a source-area chronology and the strength of correlation are important considerations when evaluating the efficacy of sourcing results. To test whether changing these parameters would affect our results, we created three subsets of the sourcing results based on series length (number of rings) and strength of correlation (t values). Researchers tend to use long series (i.e., more rings) to protect against spurious correlations from low n values, or to group the archaeological tree-ring series into a single, long chronology for sourcing (e.g., refs. 21 and 22). When analyzing the origins of individual specimens, series lengths fewer than 50–75 rings are less common, but beams with 40–50 rings have been successfully sourced (47). Given the high growth variability and strength of cross-dating in our sample of great-house timbers, we use sourcing techniques on specimens with ≥30 rings. To test whether our results were robust against a change in minimum series length, we analyzed a subset of the data that included only those specimens with ≥75 rings, yielding 131 great-house timbers. Although no universal threshold exists for determining matches between beams and source-area chronologies, one of the most conservative minimum t values is 6. Therefore, we created a second subset with beams that sourced with t ≥ 6, yielding 117 great-house timbers. Finally, we combined these two criteria to include only beams with ≥75 rings and t ≥ 6, yielding 97 timbers.

Results of these conservative subsets match the full dataset in terms of sourcing locations (Table S3) and the shift from Zuni to Chuska procurement (Fig. S6). The greatest change is for Chuska-origin beams, which are reduced in number with increasingly stringent criteria. The overall pattern, however, is maintained, supporting our use of the full dataset of 170 beams to better represent the tree-ring archaeological record from the great houses of Chaco Canyon.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Navajo Nation and the Navajo Forestry Department in particular for permission to sample on Narbona Pass. We were aided in the field and laboratory by E. Ahanonu, C. D. Allen, A. Arizpe, C. H. Baisan, E. Bigio, R. Brown, C. Dwyer, J. Farella, J. Johnston, A. Macalady, K. Miller, T. Murphy, and A. Penaloza. Archaeological tree-ring records were digitized and their associated specimens retrieved by P. P. Creasman and G. D. Flax. Edward Cook provided invaluable assistance with the archaeological chronologies. We thank A. Heisey for use of his Pueblo Bonito photo in Fig. 1, J. Betancourt for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript, D. Meko for statistical advice, and D. Ford and B. Mills for their many insights and support. This study was supported by Western National Parks Association Grant 13-02 and National Park Service Desert Southwest Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Units Grant UAZDS-381. Additional support was provided by National Science Foundation Dynamics of Coupled Natural and Human Systems Award 1114898 (to T.W.S.) and by the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: All tree-ring data used here are available in Dataset S1. Tree-ring chronologies developed as part of this study are available on the International Tree-Ring Data Bank, www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/paleoclimatology-data/datasets/tree-ring (accession nos. NM588 and NM589). The database of great house beams is available on the Chaco Research Archive, www.chacoarchive.org/cra/chaco-resources/tree-ring-database.

See Commentary on page 1118.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1514272112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lekson SH, editor. The Archaeology of Chaco Canyon: An Eleventh-Century Pueblo Regional Center. School of American Research Press; Santa Fe, NM: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doyel DE ed. (1992) Anasazi Regional Organization in the Chaco System. Anthropological Paper No. 5 (Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, Univ of New Mexico, Albuquerque)

- 3.Dean JS, Warren RL. Dendrochronology. In: Lekson SH, editor. The Architecture and Dendrochronology of Chetro Ketl, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. US Department of the Interior National Park Service; Albuquerque, NM: 1983. pp. 105–240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betancourt JL, Dean JS, Hull HM. Prehistoric long-distance transport of construction beams, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Am Antiq. 1986;51(2):370–375. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durand SR, Shelley PH, Antweiler RC. Trees, chemistry, and prehistory in the American Southwest. J Archaeol. 1999;26(2):185–203. [Google Scholar]

- 6.English NB, Betancourt JL, Dean JS, Quade J. Strontium isotopes reveal distant sources of architectural timber in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(21):11891–11896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211305498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds AC, et al. 87Sr/86Sr sourcing of ponderosa pine used in Anasazi great house construction at Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. J Archaeol Sci. 2005;32(7):1061–1075. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drake BL, Wills WH, Hamilton MI, Dorshow W. Strontium isotopes and the reconstruction of the Chaco regional system: evaluating uncertainty with Bayesian mixing models. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e95580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wills WH, Drake BL, Dorshow WB. Prehistoric deforestation at Chaco Canyon? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(32):11584–11591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409646111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Windes TC, Ford D. The Chaco wood project: The chronometric reappraisal of Pueblo Bonito. Am Antiq. 1996;61(2):295–310. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Windes TC, McKenna PJ. Going against the grain: Wood production in Chacoan society. Am Antiq. 2001;66(1):119–140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mills BJ. Recent research on Chaco: Changing views on economy, ritual, and society. J Archaeol Res. 2002;10(1):65–117. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Judd NM. The Material Culture of Pueblo Bonito. Smithsonian Institution; Washington, DC: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Betancourt JL, VAN Devender TR. Holocene vegetation in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Science. 1981;214(4521):656–658. doi: 10.1126/science.214.4521.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betancourt JL, Van Devender TR, Martin PS. Fossil packrat middens from Chaco Canyon, New Mexico: Cultural and ecological significance. In: Wells S, Love D, Gardner T, editors. Chaco Canyon Country, A Field Guide to the Geomorphology, Quaternary Geology, Paleoecology, and Environmental Geology of Northwestern New Mexico. American Geomorphological Field Group; Albuquerque, NM: 1983. pp. 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall SA. Prehistoric vegetation and environment at Chaco Canyon. Am Antiq. 1988;53(3):582–592. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bridge M. Locating the origins of wood resources: A review of dendroprovenancing. J Archaeol Sci. 2012;39(8):2828–2834. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baillie M, Hillam J, Briffa K, Brown D. Re-dating the English art-historical tree-ring chronologies. Nature. 1985;315:317–319. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wazny T. Baltic timber in Western Europe–an exciting dendrochronological question. Dendrochronologia. 2002;3:313–320. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haneca K, Wazny T, Van Acker J, Beeckman H. Provenancing Baltic timber from art historical objects: success and limitations. J Archaeol Sci. 2005;32(2):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin-Benito D, et al. Dendrochronological dating of the World Trade Center ship, Lower Manhattan, New York City. Tree-Ring Res. 2014;70(2):65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creasman PP, Baisan CH, Guiterman CH. Dendrochronological evaluation of ship timber from Charlestown Navy Yard (Boston, MA) Dendrochronologia. 2015;33:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 23.St. George S, Ault TR. The imprint of climate within Northern Hemisphere trees. Quat Sci Rev. 2014;89:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheppard P, Comrie A, Packin G, Angersbach K, Hughes M. The climate of the US Southwest. Clim Res. 2002;21:219–238. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cropper JP, Fritts HC. Density of tree-ring grids in western North America. Tree Ring Bull. 1982;42:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fritts HC. Relationships of ring widths in arid-site conifers to variations in monthly temperature and precipitation. Ecol Monogr. 1974;44(4):411–440. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baillie MGL, Pilcher JR. A simple crossdating program for tree-ring research. Tree-Ring Bull. 1973;33:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Betancourt JL. Late Quaternary biogeography of the Colorado Plateau. In: Betancourt JL, Van Devender TR, Martin PS, editors. Packrat Middens: The Last 40,000 Years of Biotic Change. Univ of Arizona Press; Tucson, AZ: 1990. pp. 259–292. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benson LV. Development and application of methods used to source prehistoric Southwestern maize: a review. J Archaeol Sci. 2012;39(4):791–807. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimstead DN, Reynolds AC, Hudson AM, Akins NJ, Betancourt JL. Reduced population variance in strontium isotope ratios informs domesticated turkey use at Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, USA. J Archaeol Method Theory. 2014;21:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cameron CM. Pink chert, projectile points, and the Chacoan Regional System. Am Antiq. 2001;66(1):70–101. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toll HW. Ceramic comparisons concerning redistribution in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. In: Howard H, Morris EL, editors. Production and Distribution: A Ceramic Viewpoint. BAR International Series No. 120; Oxford: 1981. pp. 83–121. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mills BJ, Carpenter AJ, Grimm W. Sourcing Chuskan ceramic production: Petrographic and experimental analyses. Kiva. 1997;62(3):261–282. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crown PL, Hurst WJ. Evidence of cacao use in the Prehispanic American Southwest. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(7):2110–2113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812817106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watson AS, et al. Early procurement of scarlet macaws and the emergence of social complexity in Chaco Canyon, NM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(27):8238–8243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509825112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Touchan R, Woodhouse CA, Meko DM, Allen CD. Millennial precipitation reconstruction for the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico, reveals changing drought signal. Int J Climatol. 2011;31:896–906. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grissino-Mayer HD. Evaluating crossdating accuracy: A manual and tutorial for the computer program COFECHA. Tree-Ring Res. 2001;57(2):205–221. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook ER, Peters K. The smoothing spline: A new approach to standardizing forest interior tree-ring width series for dendroclimatic studies. Tree-Ring Bull. 1981;41:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 39.R Core Team 2014 R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available at www.R-project.org/

- 40.Bunn AG. A dendrochronology program library in R (dplR) Dendrochronologia. 2008;26:115–124. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dean JS, Funkhouser G. Dendroclimatic reconstructions for the southern Colorado Plateau. In: Waugh WJ, Peterson KL, Wigand PE, Louthan BD, Walker RD, editors. Climate in the Four Corners and Adjacent Regions: Implications for Environmental Restoration and Land-Use Planning. US Department of Energy, Grand Junction Projects Office; Grand Junction, CO: 1995. pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bigio ER. 2013. Late Holocene fire and climate history of the western San Juan Mountains, Colorado: Results from alluvial stratigraphy and tree-ring methods. PhD dissertation (Univ of Arizona, Tucson, AZ)

- 43.Mills BJ, Clark JJ, Peeples MA. 2014. Chaco Social Networks Site Database version 1.0 (Archeology Southwest, Tucson, AZ)

- 44.Kantner JW, Kintigh KW. The Chaco world. In: Lekson SH, editor. The Archaeology of Chaco Canyon: An Eleventh-Century Pueblo Regional Center. School of American Research Press; Santa Fe, NM: 2006. pp. 153–188. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daly A. 2007. Timber, trade and tree-rings: A dendrochronological analysis of structural oak timber in northern Europe, C. AD 1000 to C. AD 1650. PhD dissertation (Univ of Southern Denmark, Denmark)

- 46.Windes TC. 2006. Early Puebloan occupation in the Chaco Region: Excavations and survey of Basketmaker III and Pueblo I sites (Anthropology Projects, Cultural Resources Management, Intermountain Region Support Office, National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Santa Fe, NM)

- 47.Sass-Klaassen U, Vernimmen T, Baittinger C. Dendrochronological dating and provenancing of timber used as foundation piles under historic buildings in The Netherlands. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2008;61(1):96–105. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kampstra P. Beanplot: A boxplot alternative for visual comparison of distributions. J Stat Softw. 2008;28:1–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.