Abstract

The post-natal period in mammals represents a developmental epoch of significant change in the autonomic nervous system (ANS). In this study we focus on post-natal development of the area postrema, a crucial ANS structure that regulates temperature, breathing, and satiety, amongst other activities. We find that the human area postrema undergoes significant developmental changes during post-natal development. To further characterize these changes, we utilized transgenic mouse reagents to delineate neuronal circuitry. We discovered that although a well-formed ANS scaffold exists early in embryonic development, the area postrema shows a delayed maturation. Specifically, postnatal days 0 to 7 in mice show no significant change in area postrema volume or synaptic input from PHOX2B-derived neurons. In contrast, postnatal days 7-20 shows a significant increase in volume and synaptic input from PHOX2B-derived neurons. We conclude that key ANS structures show an unexpected dynamic developmental changes during post-natal development. These data provide a basis for understanding ANS dysfunction and disease predisposition in premature and post-natal humans.

Keywords: Area postrema, PHOX2B, interoception, circumventriculate organ, post-natal development, autonomic nervous system

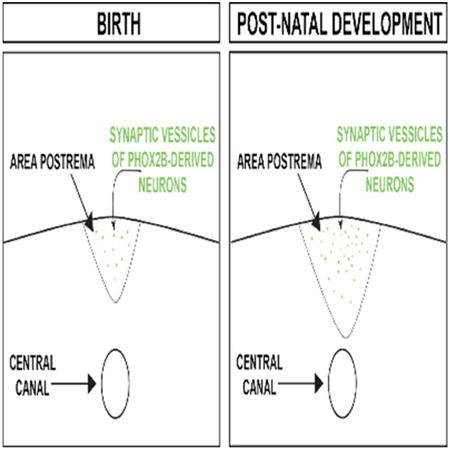

Graphical abstract

The area postrema is a major integrator of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). At birth, mammals show ANS immaturity resulting in generalized dysautonomia. Here, Gokozan et al. by combining modern and traditional neuroanatomical tools demonstrate that the development of the area postrema dynamically changes during postnatal development in mice and humans. These changes include a significant increase in size and increase in the innervation during the post-natal epoch. The graphical abstract above illustrates the increase in area postrema size and in synaptic vessicles derived from PHOX2B-derived neurons that we identified in this work.

Introduction

Although infant inability to autonomously feed is self-evident, autonomic nervous system (ANS) immaturity at birth represents a developmental conundrum. Newborns must regulate breathing, temperature, satiety, and heart rate (amongst other physiological processes) to survive the ex utero environment. Nevertheless, the ANS shows significant physiological changes during late embryonic and post-natal epochs. Newborn human infants have a well-documented vulnerability to thermal stress (Knobel and Holditch-Davis, 2007). Similarly, incomplete maturity and/or absence of autonomic neuron networks are a proposed mechanism of infant breathing disorders including apnea of prematurity and sudden infant death syndrome (Hunt, 2006).

The homeobox transcription factor PHOX2B regulates ANS function as well as the specification of noradrenergic neurons (Tiveron et al., 1996; Pattyn et al., 1997; Swanson et al., 1997; Kim et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998; Stanke et al., 1999). All autonomic afferent and efferent circuits require normal PHOX2B function to develop properly. PHOX2B+/- mice suffer mild dysautonomia (Cross et al., 2004), whereas PHOX2BLacz/Lacz mice show embryonic lethality (Pattyn et al., 1999). In 2003 Amiel et al. published the first evidence that congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS) is caused by polyalanine expansions of the paired-like homeobox gene PHOX2B (Amiel et al., 2003). CCHS patients have absent or greatly diminished ventilatory responses to hypercapnia or hypoxia (Spengler et al., 2001; Gaultier and Gallego, 2005). The proposed mechanism is a selective impairment of central chemosensory integration rather than a dysfunction of the respiratory pattern generator, CPG, because breathing is typically adequate when CCHS patients are awake and their ventilation increases normally during mental stimulation or exercise hypoxia (Spengler et al., 2001; Gaultier and Gallego, 2005). However, when asleep, CCHS patients experience life-threatening hypoventilation or complete apnea. In short, the symptoms of CCHS support the existence of neurons that selectively mediate the chemical drive to breathe and suggest that these neurons are especially important during sleep. In rodents, PHOX2B expression is required for the development of the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), brainstem catecholaminergic neurons, carotid bodies, enteric nervous system, sympathetic ganglionic (but not preganglionic) neurons and the cranial parasympathetic system but not required for the serotonergic system (Dubreuil et al., 2009). PHOX2B expression persists in most brainstem structures after birth (Dauger et al., 2003), which has allowed us to demonstrate that this gene is expressed by the hypercapnia-sensitive neurons of the brainstem that mediate chemoreflexes (Stornetta et al., 2006). However, the extent to which these crucial connective circuits amongst chemosensory organs change during the postnatal period remains poorly understood.

The chemosensory organs are contained within specialized areas of the brain that are in contact with blood due to the unique circulatory structure. These areas are termed sensory circumventricular organs and amongst them is the Area Postrema (AP). AP neurons sense and integrate blood-borne baroreceptor information from the carotid sinus and aorta, osmoreceptor information from the liver, and mechanical information via stretch receptors in the stomach (reviewed by (Price et al., 2008). Another important but less well-studied role for the AP neurons is in the stimulation of respiratory drive. AP neurons have been shown to contribute to respiratory responses by increasing respiratory rate when stimulated independent of arterial blood pressure as well as decreasing respiratory rate when damaged (Srinivasan et al., 1993; Bongianni et al., 1998). During development, the AP receives innervation from PHOX2B-derived noradrenergic cells positive for Dopamine Beta Hydroxylase (DBH) (Pangestiningsih et al., 2009). Thus, connections between AP chemosensors and the noradrenergic autonomic nuclei may function to integrate autonomic homeostasis. Therefore, the goal of our study was to understand the developmental processes occurring in post-natal ANS circuits so as to gain basic knowledge regarding the processes occurring during these critical time periods.

Materials and Methods

Animal husbandry

Experimental Animals

PHOX2B-cre mice (Jax # 16223, RRID = IMSR_JAX:016223) were bred with ROSA ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP mice (Jax # 7676, RRID = IMSR_JAX:007676, referred to herein as “ROSA mice”). To identify the developmental origin of neuron networks, we utilized B6;129-Iis1tm1(CAG-Bgeo,-tdTomato/TEVP,-SV2B/GFP)Nat/J (Jax# 010590, RRID = IMSR_JAX:010590, referred to herein as “tracer mouse”).

Histology, and unbiased stereology

Human pediatric brainstem fixation

Case 1, a pre-term female infant born at 22 weeks GA and which died at birth (pre-term chorioamnionitis). Case 2, a 37 and 3/7 weeks gestation that expired at 2 days of life due to respiratory distress. Case 3, a 16 week-old male infant born at 38 and 5/7 weeks gestational age with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. (IHC) studies employed: Dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) (Santa Cruz SC365710, 1:100, RRID = AB_10844004, and Santa Cruz, SC15318, 1:100, RRID = AB_2089347), developed with DAB (Dako # K4004/K4011). Antigen retrieval and histology was performed as described previously (Otero et al., 2014). Samples from a CCHS proband with an 8 nucleotide deletion in exon 3 and appropriate control is derived from FFPE archival tissue previously published by our group (Otero, 2011; Nobuta, 2015).

Mouse histology

Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (30 mg/mL) and xylazine (2 mg/mL) in saline for transcardial perfusion with PBS followed by 4% PFA. E14.5 embryos were removed from timed-pregnant females and drop-fixed in 4% PFA. After sucrose equilibration, hindbrains or whole embryos were embedded coronally in OCT and frozen on dry ice. Primary antibodies used included anti-GFP (Aves Lab GFP-1020, 1:500, RRID = AB_10000240), anti-RFP (Clontech, 632496, 1:100, RRID = AB_10013483), and anti-HA (kind gift of Jeremy Nathans, RRID not available).

Antibody Characterization

Anti-GFP antibody has been well-characterized and previously published in this Journal (Tan et al., 2010). Validations for anti-HA, anti-GFP and anti-RFP were performed using cre-negative tracer mice, which do not express HA, tdTomato, or GFP; no immunoreactivity was identified in the cre-negative littermates. DBH antibodies were utilized to label noradrenergic neurons. DBH immunohistochemistry on human sections was validating by matching the immunohistochemal result with known anatomical locations of noradrenergic neurons with a standard neuroanatomy atlas (DeArmond et al., 1989). Immunoreactivity was observed only in noradrenergic nuclei and their neurites. The rabbit DBH antibody was used in archival formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissue. The mouse DBH antibody was used for formalin-fixed, sucrose equilibrated, OCT-embedded frozen material.

Unbiased stereology

All unbiased stereology was performed using Stereoinvestigator v11 (MBF Biosciences, RRID = SciRes_000114). Cavalieri estimations was performed as described previously by our group (Otero et al., 2014; Chang, 2015). For human and mouse volumetric analysis, every tenth section and every section, respectively, were investigated and Cavalieri estimation generated volume estimates with the following parameters: Counting was performed under 10× objective, grid size= 30 μm, shape factor= 4. Optical fractionator determined the total number of HA+ SV2B synaptic punctae of TracerX PHOX2Bcre mouse AP. Each representing tissue section was investigated for mouse area postrema synaptic vesicle quantification. Optical fractionator probes used with the following parameters: 100x objective, dissector height= 20 μm, dissector volume= 50000μm3, counting frame height and width= 50 μm, sampling grid= 153.9 μm × 162.5 μm. Statistical analysis of neurite length density was performed by Stereoinvestigator/Spaceballs software (Mouton, 2002). Specific parameters used included a probe radius of 8.3 μm, section thickness of 20 μm, probe surface area of 437 μm2, and the section sampling fraction was one in ten sections sampled. Length, length density, and coefficient of error was calculated by Spaceballs workflow. ANOVA/Tukey HSD test was implemented using R v2.12 (RRID = nif-0000-1047). The significance was set to p < 0.05.

Results

Dynamic Post-natal Growth of the Human AP

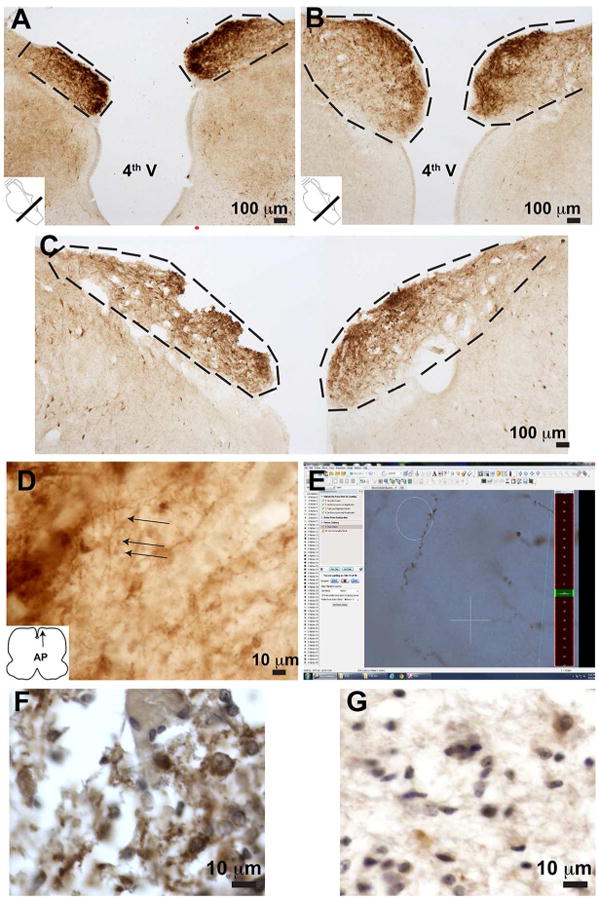

The human AP appears during weeks 10-15 gestation as two sulci/recesses in the ventricular wall. By week 16-29, the AP shows distinguished vasculature and protrudes into the 4th ventricle. By 30-40 weeks the human neurons are well identifiable and it has roughly an adult morphology (Castaneyra-Perdomo et al., 1992). We thus set forth to characterize the late embryonic and post-natal changes of the human AP. We note that the AP is intensely positive for Dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) (Fig. 1), the rate-limiting enzyme for noradrenalin biosynthesis. Furthermore, DBH immunohistochemical morphology allows one to identify the neurites of DBH-positive neurons. We therefore used this to identify the neurite length-density, which can be used as a proxy for the extent of innervation in such studies (Calhoun and Mouton, 2000; Mouton et al., 2002) (Fig.1). Note that in humans, the AP is a bilateral medullary circumventriculate organ, located on the dorsal medulla (Figs. 1A-D). Our stereological quantifications generated unbiased estimates with very low coefficients of error. Furthermore, in our study set, we found that the AP undergoes significant dynamic changes (Figs. 1A-C, Table 2A and Table 2B). To determine the extent to which the AP was affected in CCHS, we performed DBH immunohistochemistry on archival FFPE tissue. Note the decreased intensity of DBH immunohistochemistry in CCHS relative to the control (Fig. 1G). We conclude that the human AP undergoes significant developmental changes during the third trimester and the postnatal developmental epoch and that noradrenergic neuron formation in the AP of CCHS patients is defective. These data are in line with recent reports demonstrating significant noradrenergic dysfunction in CCHS (Nobuta et al., 2015).

Figure 1. Post-natal Growth of Human Area Postrema.

Panels A, B, and C represent images of both AP's post-DBH IHC. All samples images are derived from human samples (see methods). The AP was delineated experimentally morphologically as indicated by the dashed black lines in Panels A-C. Measurements are presented in Table 2A and 2B. Panel A = Case 1, 22 week gestation age deceased at birth; Panel B= Case 2, 40 week gestational age deceased at birth; Panel C = Case 3, 40 week gestational age deceased at 4 months. (D) Typical DBH-positive neurite morphology. (E) Screenshot of Spaceballs user interface illustrating example DBH-positive neurite with spaceballs. Analysis of post-morten, formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue (F and G). Panel F represent the control for Panel G, a proband with an NPARM PHOX2B mutation.

Table 2A. DBH Length Quantification in Human Area Postrema.

| Parameter | Case 1 22 week GA, Deceased at Birth |

Case 2 37 3/7 week GA, Deceased at Birth |

Case 3 38 5/7 week GA, Deceased at 4 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Length of DBH-positive processes (μm) | 5.9 × 106 | 16.7 × 106 | 27.5 × 106 |

| Coefficient of error, m=0 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.07 |

| Section Evaluation Interval | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Number of sections | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| Section cut thickness | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Measured mean thichness mounted section (μm) | 22 | 21.4 | 20.6 |

| Radius of hemo-spaceball (μm) | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| Area of Spaceball probe (μm2) | 432.8 | 432.8 | 432.8 micron sq |

| Volume of spaceball probe (μm3) | 549533.81 | 535121.56 | 515401 |

| Sampling grid area (XY μm2) | 25006.8 | 25006.8 | 25006.8 |

| Number of Sampling sites | 65 | 176 | 333 |

Table 2B. Area Quantification of Human Area Postrema.

| Parameter | Case 1 22 week GA, Deceased at Birth |

Case 2 37 3/7 week GA, Deceased at Birth |

Case 3 38 5/7 week GA, Deceased at 4 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Volume (μm3) | 3.77 × 108 | 10.3 × 108 | 19.9 × 108 |

| Coefficient of error, m=0 | 0.012 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Section Evaluation Interval | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Number of sections | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| Section cut thickness | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Grid Size (μm) | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Count | 1774 | 4845 | 8823 |

A Scaffold for the ANS is Established Early During Embryonic Development

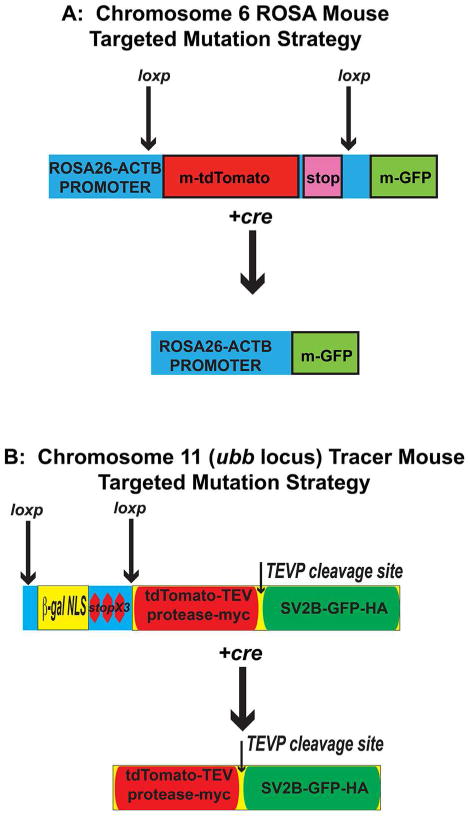

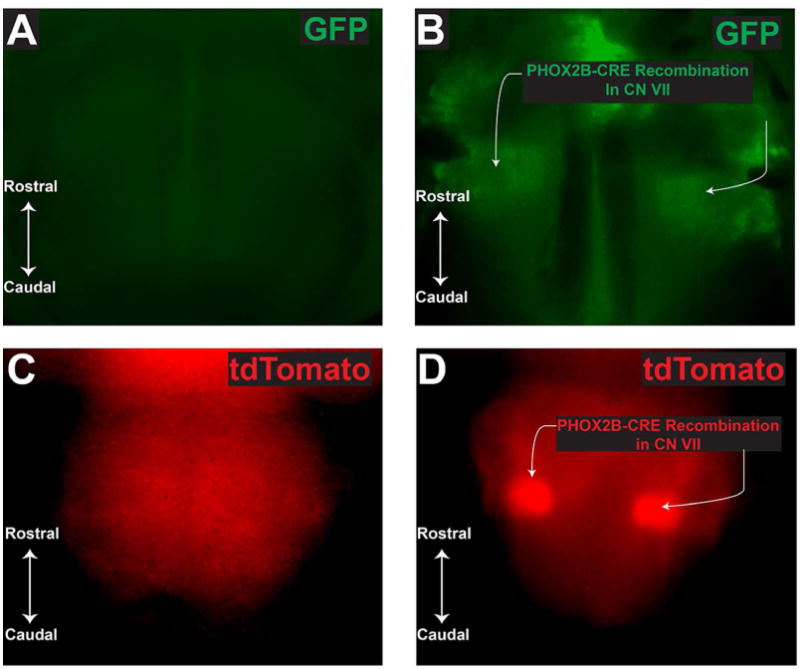

The PHOX2B expression domain has been well-characterized in the scientific literature (Pattyn et al., 1999; Coppola et al., 2010). Furthermore, PHOX2B in situ hybridization analysis of the developing mouse brain is well-annotated in the Allen Brain Atlas (http://developingmouse.brain-map.org/gene/show/18698). These and other studies have utilized labeling reagents that are limited to the cell nucleus or the cytoplasm and are not intentionally designed to evaluate architecture of ascending/descending/decussating tracts. To further characterize the changes of the developing autonomic nervous system, we utilized distinct transgenic mouse reagents. Current experimental paradigms that investigate brainstem circuitry often utilize antero/retrograde based dyes (De Lacalle et al., 1996), or neurotropic virus-based methodologies (Beier et al., 2011). These studies have proven quite instructive in determining neuron networks in adults, but are challenging to implement in human studies or in rodent experimental models at the time points pertinent to human perinatal breathing disorders. Another limitation of these methods is that they cannot provide any information on the developmental lineage of the traced neurons. Here we utilized a genetic method study the development of the ANS during embryonic and postnatal time periods (Fig. 2). Briefly, this ROSA mouse shows a membrane-tethered tdTomato in the absence of cre-recombinase, and a membrane-tethered GFP after cre-mediated recombination whereas the tracer mouse shows SV2B-GFP-HA fusion protein accumulation at the presynaptic terminal of neurons post-cre-mediated recombination (Fig. 2A) due to SV2B accumulation in synaptic vesicles (Bajjalieh et al., 1994). These mice were bred to PHOX2B-cre mice (Scott et al., 2011) to induce cre-mediated recombination in cells derived from the PHOX2B lineage. Interbreeding PHOX2B-cre mice with either the ROSA mice or the Tracer mice resulted in expected mendelian ratios. Figures 3A-D demonstrate the extent to which successful cre-mediated recombination can be identified using epifluorescent photomicroscopy immediately after brain dissection. As a comparison, Figure 3A-B shows images of PHOX2B-cre X ROSA, which demonstrate GFP expression in CN VII. Note that the PHOX2B-cre X Tracer mouse (Figure 3D) shows a much more robust expression of tdTomato relative to the ROSA comparison. We conclude that Tracer mouse expression of its reporter genes show similar to increased expression relative to the more standard ROSA gene trap.

Figure 2. Transgenic Mouse Experimental Strategies.

(A) The ROSA mouse has been extensively characterized in the literature (see methods). In the absence of cre, all cells of the Rosa mouse express TdTomato; after cre-mediated excision, the TdTomato locus is excised and the cell now expresses GFP. (B) The tracer mouse has 2 kb upstream of the ubb gene a targeted insertion with a beta-galactosidase-nuclear localization cassette with 3 stop codons at the 3′ end flanked by loxp sites. After cre-mediated excision occurs in neurons, a single large protein is made containing, from amino to carboxy terminal, tdTomato-tobacco etched viral protease (TEVP)-myc epitope tag, a TEVP cleavage site, synaptic vesicle protein-GFP-hemaglutinin fusion protein. Shortly after translation, a TEVP-dependent cleavage occurs leading to generation of two cleavage products. When recombination occurs in neurons, the amino terminal protein containing tdTomato-TEVP labels all axons and dendrites, whereas the SVP2b-GFP fusion protein labels all presynaptic structures. Epitope tags on the tdTomato-TEVP for myc and SVP2b-GFP for hemaglutinin aid in immunolabelling these structures in histological applications.

Figure 3. Gross evaluation of reporter gene expression in Tracer mice.

Panel A represents GFP fluorescence from ROSA mouse negative for PHOX2B-cre. Panel B demonstrates GFP fluorescence from ROSA mouse positive for PHOX2B-cre. GFP expression in (B) demonstrates successful recombination in the 7th cranial nerve. Panel C denotes tdTomato fluorescence in tracer mouse negative for PHXO2B-cre. Panel D illustrates tdTomato fluorescence in tracer mouse positive for PHOX2B-cre. In (D), tdTomato expression (red) demonstrates successful recombination in the tracer mouse with a similar gross-distribution to the standard ROSA mouse. A-B mouse age is p26, C-D mouse ages were P0. Photographs are taken using an epifluorescent camera in the red and green filters.

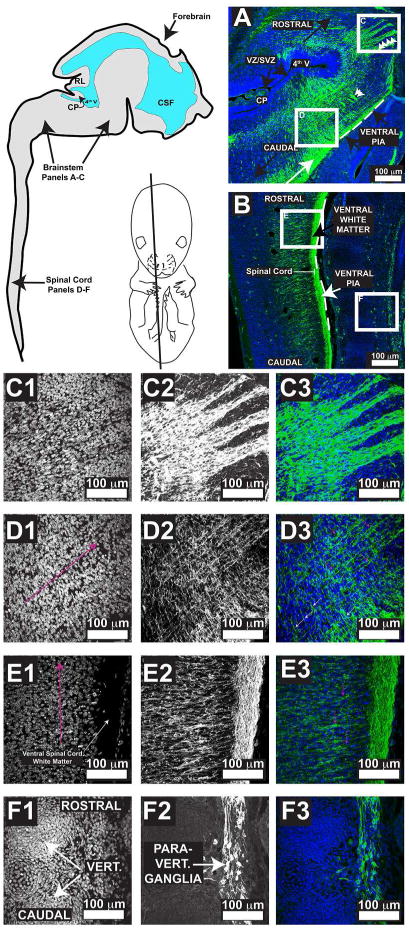

ROSA positive E14.5 mice were evaluated by immunofluorescence with anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 4). Figure 4A demonstrates a low magnification field of the brainstem, with schematics on the left showing general orientation. Figure 4A shows the ventr0-lateral medulla with an abundant accumulation of GFP positive staining corresponding to CN VII. Note however, the extensive architecture of the projections. We find an extensively elaborate scaffold of PHOX2B-derived cells showing fibers oriented in 3 dimensions (Fig. 4 A (arrowheads)). High magnification images from are shown in Figure 4D3 demonstrating fibers that are oriented parallel or antiparallel to the neuraxis (white and magenta arrowheads, respectively; neuraxis orientation demonstrated in Figure 4D1 in magenta with arrowhead pointing rostrally). This relationship was particularly appreciated in the brainstem, where we noticed bundles of tracks in rostro-caudal, dorsal-ventral, and medial lateral orientation with a “C-shaped” cytoarchitecture (Figs. 4 A; C1-C3). Furthermore, well-formed tracks throughout the extent of the spinal ventral white matter were noted. Note in Figure 4E2 that several fibers antiparallel to the neuraxis are GFP positive, as if “feeding into or out” the ventral spinal cord white matter. These data point to a previously undescribed circuit of PHOX2B-derived cells into spinal cord. Although spinal cord dysfunction-induced ANS dysfunction has been well described in spinal cord injury (reviewed by (Karlsson, 2006), the contribution of PHOX2B-derived cells to these circuits had not been appreciated. We conclude that a scaffold of ANS structures throughout the neuraxis is generated by E14.5 in murine embryonic development. However, we also found it difficult to identify the polarity of the projections using this type of transgenic reagent design. Note in Figure 4C, the extensive projections extending from the dorsal aspect of the midbrain/hindbrain junction to the ventral aspect. It is very difficult to identify where the cell bodies of these cells lie. We conclude that a transgenic reagent capable of demonstrating aspects of neuronal polarity may be better suited to identify neuronal circuits.

Figure 4. The Murine Autonomic Nervous System Shows Extensive Embryonic Development by E14.5.

Murine E14.5 neuraxis illustrates a schematic for orientation of panels A-F in addition to showing the approximate plane of section. Panels A-B, Blue = DAPI and Green = GFP. Panels A and B show white boxed panels that denote the relative location of the high magnification pictures in C-F. For ease of interpretation and orientation, panels C-F are illustrated with black and white images as well as merged image showing blue as DAPI and green as GFP. Panels C1, D1, E1, and F1 show DAPI. Panels C2, D2, E2, and F2 show GFP. Panels C3, D3, E3, and F3 are merged. Abbreviations include: CP = choroid plexus, RL = rhombic lip, CSF = cerebrospinal fluid, VZ/SVZ = ventricular zone/subventricular zone, vert. = vertebral body, Para-vert. = paravertebral. White double arrows indicate medial-lateral projections. White arrow in A demonstrates CN VII. In E1 and F1, the orientation of the neuraxis is demonstrated with the magenta arrow, with the arrowhead pointed towards the rostral end of the neuraxis. In panel D3 and E3, magenta colored arrows point to PHOX2B-derived fibers that are parallel and antiparallel, respectively, to the neuraxis. In panel C3, the white arrows point to fibers antiparallel to the neuraxis. Note in panel C3 that the polarity of the cells is not well defined using this ROSA reagent, underscoring the need for reagents that show polarized signals such as the Tracer mouse.

Delayed Postnatal Maturation of Area Postrema in Mice

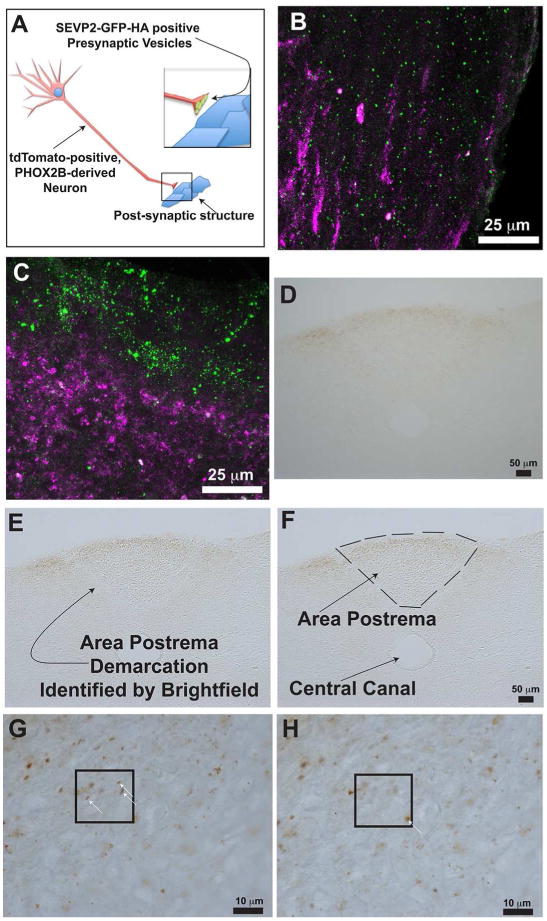

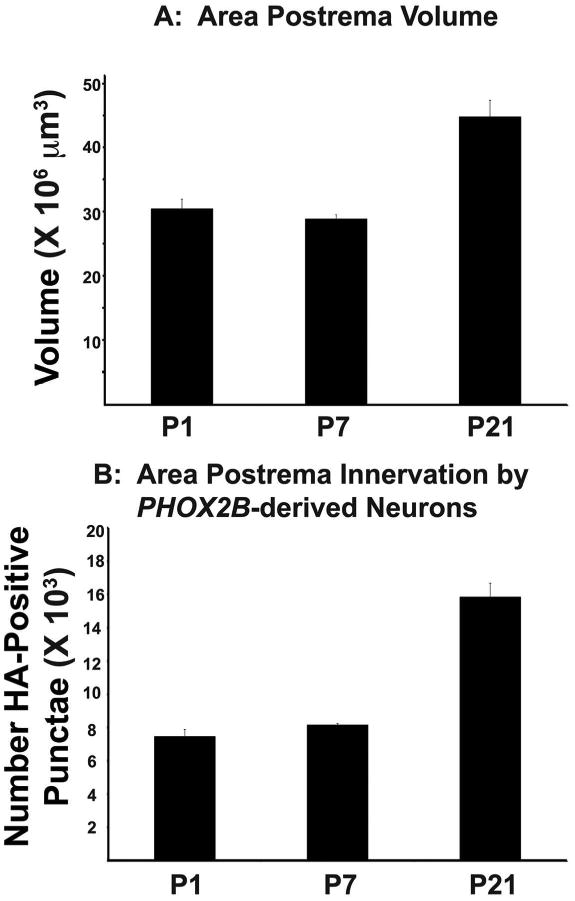

So that we could better characterize the post-natal developmental changes of the AP, we interbred tracer mice with PHOX2B-cre mice and evaluated AP maturation with histological and stereological methodologies (Fig. 5A). This permitted us to measure both the post-natal volumes in addition to identifying the extent to which synaptic inputs in the AP change during this time period in mice. With our tracer mouse experimental model, synaptic vesicles from PHOX2B-derived neurons are identified as small punctae that are GFP-positive and HA-positive (Figs. 5B and C). During the Po-> P7 epoch, the AP volume did not significantly change significantly (Figs. 5I). However, during the P7 -> P21 epoch, the AP showed significant volumetric growth (Fig. 5I). As a proxy for autonomic circuitry innervation, we measured the number of HA-positive vesicles of the AP during (Figs. 5D-H). Interestingly, the results from the HA antibody immunohistochemistry mirrored the AP volumetric data. Specifically, no significant difference in the number of HA-positive vesicles was identified during the Po -> P7 epoch, whereas a significant increases in was identified during the P7->p21 epoch (Figs. 6A-B). We conclude that the murine AP undergoes significant post-natal volumetric growth in addition to increased innervation as demonstrated by the significant increase in SV2B-GFP-HA-positive vesicles in the AP.

Figure 5. Tracer Mouse Validation and Morphometric Quantification of Area Postrema Workflow.

Schematic in (A) illustrates this concept. A PHOX2B-derived neuron undergoes cre-mediated recombination, resulting in expression of cytosolic tdTomato and SEVP2-GFP-HA in the synaptic vesicles. Panels B and C show maximum intensity projections of confocal z-stack images. Panel B illustrates the ventrolateral medulla. Panel C illustrates the area postrema. In Panels B and C, the green punctae represent SEVP2-GFP-HA, and the magenta colored processes represent tdTomato-positive signals. Note that GFP localizes to the ventral side of the are postrema in panel C. Panels (D) through (H) illustrate synaptic input quantification workflow. We utilized an anti-HA antibody to label the SEVP2-GFP-HA presynaptic vesicles and developed the immunohistochemical reaction with DAB resulting in a brown precipitate (Step 1, D). The AP's anatomical boundaries are easily determined by adjusting the microscope's condenser settings (Step 2, E), which shows a bright line separating the AP from the lateral brainstem neuropil. We then demarcated the area of interest in Stereoinvestigator™ (Step 3, F) and commenced the optical fractionator workflow (Step 4, G-H). White arrows in G and H illustrate example punctae that we quantified. Panels G and H represent that same microscopic field, but at a different focal plane.

Figure 6. Morphometric Quantification of the Area Postrema.

(A) Cavalieri estimation of the Area Postrema volume based on morphological boundaries (see figure Figure 4 and Materials and Methods). X-axis is post-natal age. Y-axis is total estimated volume of Area Postrema (B). Optical fractionator quantification of the HA-positive punctae, which represent synaptic vesicles derived from PHOX2B-positive cells. X-axis is the post-natal age, and the Y-axis is the total estimated number of HA-positive punctae.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the development of the AP during post-natal human and mouse development. Our experiments are the first instance to our knowledge of combining these neuroanatomical techniques with the power of transgenic mice genetically engineered to identify the developmental origins of neuronal circuits. The techniques delineated in this manuscript provide a technical foundation for future experiments that seek to measure, in an unbiased fashion, the extent to which innervations and connections mature over time. Furthermore, our novel data regarding postnatal AP development provides additional mechanistic insight into known challenges of postnatal autonomic nervous system development.

Translational Significance of Post-natal Area Postrema Changes

The extent to which ANS dysfunction leads to deficient homeostasis in premature babies is intensely debated in the literature. For instance, temperature control is classically considered an ANS-controlled physiological process, and post-natal temperature control remains crucial to appropriate patient management (Laptook and Watkinson, 2008). Nevertheless, premature infants have several environmental challenges that may mediate this thermal dysregulation. Proposed environmental mechanisms have included the known correlation between increased transepidermal water loss with decreasing gestational age (Hammarlund and Sedin, 1982). Such data suggest that these defects are due at least in part to non-CNS regulated pathologies. Nevertheless, compelling evidence suggests that some prematurity complications result from ANS mal-development. For example, in preterm infants, hypercapnia results in longer expiratory duration and increased expiratory respiratory braking (Eichenwald et al., 1993). In addition, CO2-induced ventilation changes are significantly reduced in preterm infants independent of the stage of lung maturity (Frantz et al., 1976). Apnea of Prematurity (AOP) infants require external ventilator support until CNS respiratory centers develop postnatally. In summary, ANS dysfunction in the preterm infant is a significant contributor to pathologies in preterm babies. In addition, the contribution of the AP to chemoreflexes has been demonstrated in rats under conditions of severe hypoxia (Erickson and Millhorn, 1991; 1994; Teppema et al., 1997). In the rabbit under similar conditions, enhanced Fos expression has been observed in the whole circumventricular organs, including the Area Postrema (Hirooka et al., 1997). These regions, which are virtually devoid of blood-brain barrier, are primarily regarded as chemosensitive zones detecting changing levels of circulating substances in the blood and the cerebrospinal fluid. Their contribution to O2-chemosensitivity remains to be clarified. Furthermore, the AP might relay hypoxia-sensitive inputs to and/or from the major respiratory groups to which it is bidirectionally connected (McKinley et al., 1995).

Our findings demonstrate, for the first time, that the AP undergoes significant post-natal changes in mouse and humans, and that AP noradrenergic neurons are diminished in human CCHS, despite the finding that a well-established scaffold of ANS fibers courses throughout the brainstem and spinal cord prior to birth. Indeed, one would imagine that by birth a fully functional ANS should have formed. Yet, historical findings have long pointed to a flux in autonomic nervous system function during the post-natal epoch. For example, newborn mice are characterized by poikilothermy from post-natal day 1-7, and do not develop adult-type homiothermy until postnatal day 19-20 (Lagerspetz, 1966). Of note, these periods of poikilothermy correlate with the immature AP, whereas the onset of homiothermy occurs when the AP has the more mature phenotype. Similar evidence for post-natal changes in autonomic function can be deduced from human studies. First, the dynamic changes occurring in the post-natal AP coincide with susceptibility of human infants to sudden infant death syndrome (Duncan et al., 2010). Second, CCHS patients, especially those with PARM mutations characterized by 20/25 genotypes, manifest with hypoventilation later in life (Weese-Mayer et al., 2005; Doherty et al., 2007). In summary, evidence from the scientific literature indicates that, although counterintuitive, the ANS undergoes dynamic changes even in physiological circumstances. Our data demonstrate that the AP also changes dynamically with post-natal age, and we find that AP maturation correlates with certain disease onsets.

Table 1. List of Primary Antibodies.

| Antigen | Description of Immunogen | Source, Host Species, Cat. #, Clone, RRID | Concentration Used | RRID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-HA | Triple HA-fusion to T7 gene 10 protein, made in E. coli | Kind gift of Dr. Jeremy Nathans, Johns Hopkins University. Rabbit. Antibody Generated in Nathans Lab | 1 is to 50,000. | Not available |

| Anti-GFP | Recombinant GFP | Aves Lab, Chick IgGY, Catalogue Number GFP-1020, Lot number 0511FP12 | 1 is to 500. | AB_10000240 |

| Anti-DBH | DBH construct containing amino acids 391-603 mapping to C-terminus. | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, rabbit, cataologue number SC15318 (H13), Lot Number F1710. | 1 is to 100 | AB_2089347 |

| Anti-DBH | DBH construct containing amino acids 391-603 mapping to C-terminus. | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, mouse monoclonal IgG1, Catalogue Number SC-365710, Lot Number 10111. | 1 is to 100 | AB_10844004 |

| Anti-RFP | DsRed Express variant of Discosoma sp. Expressed in E. coli | Clontech, Rabbit polyclonal IgG, Catalogue Number 632496, Lot number 1408015 | 1 is yo 100. | AB_10013483 |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Jeremy Nathans for graceful distribution of key reagents as well as technical guidance for this work. The manuscript was written by JJO and HNG. Experiments were performed and interpreted by HNG, FB, SC, FPC, PEG, CC, and JJO. The authors have no conflict of interests to declare. Funding provided by NIBIB (1R21EB017539-01A1 and 3R21EB017539-01A1S1) and National Center for the Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001070 and 8UL1TR000090-05). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. This work was sponsored by and represents activity of The Ohio State University Center for Regenerative Medicine and Cell Based Therapies (regenerativemedicine.osu.edu).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: Experimental Design: JJO, CC, HNG, TSM, ACT.

Experimental Implementation: (Immunohistochemistry, animal breeding, and photomicroscopy) HNG, FB, SC, FPC, PEG.

Experimental Interpretation: JJO, CC, HNG, ACT, TSM.

Manuscript Writing: JJO, HNG, CC, ACT, TSM

References

- Amiel J, Laudier B, Attie-Bitach T, Trang H, de Pontual L, Gener B, Trochet D, Etchevers H, Ray P, Simonneau M, Vekemans M, Munnich A, Gaultier C, Lyonnet S. Polyalanine expansion and frameshift mutations of the paired-like homeobox gene PHOX2B in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33(4):459–461. doi: 10.1038/ng1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajjalieh SM, Frantz GD, Weimann JM, McConnell SK, Scheller RH. Differential expression of synaptic vesicle protein 2 (SV2) isoforms. J Neurosci. 1994;14(9):5223–5235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05223.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier KT, Saunders A, Oldenburg IA, Miyamichi K, Akhtar N, Luo L, Whelan SP, Sabatini B, Cepko CL. Anterograde or retrograde transsynaptic labeling of CNS neurons with vesicular stomatitis virus vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(37):15414–15419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110854108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongianni F, Mutolo D, Carfi M, Pantaleo T. Area postrema glutamate receptors mediate respiratory and gastric responses in the rabbit. Neuroreport. 1998;9(9):2057–2062. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199806220-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun ME, Mouton PR. Length measurement: new developments in neurostereology and 3D imagery. Journal of chemical neuroanatomy. 2000;20(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneyra-Perdomo A, Meyer G, Heylings DJ. Early development of the human area postrema and subfornical organ. Anat Rec. 1992;232(4):612–619. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092320416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Leung M, Gokozan HM, Gygli PE, Catacutan FP, Czeisler C, Otero JJ. Mitotic Events in Murine Cerebellar Granule Progenitor Cells that Expand Cerbellar Surface Area are Critical for Normal Cerebellar Cortical Lamination. Journal Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2015 doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000171. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola E, d'Autreaux F, Rijli FM, Brunet JF. Ongoing roles of Phox2 homeodomain transcription factors during neuronal differentiation. Development. 2010;137(24):4211–4220. doi: 10.1242/dev.056747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SH, Morgan JE, Pattyn A, West K, McKie L, Hart A, Thaung C, Brunet JF, Jackson IJ. Haploinsufficiency for Phox2b in mice causes dilated pupils and atrophy of the ciliary ganglion: mechanistic insights into human congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(14):1433–1439. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauger S, Pattyn A, Lofaso F, Gaultier C, Goridis C, Gallego J, Brunet JF. Phox2b controls the development of peripheral chemoreceptors and afferent visceral pathways. Development. 2003;130(26):6635–6642. doi: 10.1242/dev.00866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lacalle S, Cooper JD, Svendsen CN, Dunnett SB, Sofroniew MV. Reduced retrograde labelling with fluorescent tracer accompanies neuronal atrophy of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in aged rats. Neuroscience. 1996;75(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeArmond SJ, Fusco MM, Dwewey MM. Structure of the Human Brain, A Photographic Atlas. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty LS, Kiely JL, Deegan PC, Nolan G, McCabe S, Green AJ, Ennis S, McNicholas WT. Late-onset central hypoventilation syndrome: a family genetic study. The European respiratory journal. 2007;29(2):312–316. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00001606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil V, Barhanin J, Goridis C, Brunet JF. Breathing with phox2b. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological sciences. 2009;364(1529):2477–2483. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JR, Paterson DS, Hoffman JM, Mokler DJ, Borenstein NS, Belliveau RA, Krous HF, Haas EA, Stanley C, Nattie EE, Trachtenberg FL, Kinney HC. Brainstem serotonergic deficiency in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(5):430–437. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenwald EC, Ungarelli RA, Stark AR. Hypercapnia increases expiratory braking in preterm infants. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75(6):2665–2670. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.6.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JT, Millhorn DE. Fos-like protein is induced in neurons of the medulla oblongata after stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve in awake and anesthetized rats. Brain Res. 1991;567(1):11–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91430-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JT, Millhorn DE. Hypoxia and electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve induce Fos-like immunoreactivity within catecholaminergic and serotoninergic neurons of the rat brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 1994;348(2):161–182. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz ID, 3rd, Adler SM, Thach BT, Taeusch HW., Jr Maturational effects on respiratory responses to carbon dioxide in premature infants. J Appl Physiol. 1976;41(1):41–45. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.41.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaultier C, Gallego J. Development of respiratory control: evolving concepts and perspectives. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;149(1-3):3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarlund K, Sedin G. Transepidermal water loss in newborn infants. VI. Heat exchange with the environment in relation to gestational age. Acta paediatrica Scandinavica. 1982;71(2):191–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1982.tb09398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka Y, Polson JW, Potts PD, Dampney RA. Hypoxia-induced Fos expression in neurons projecting to the pressor region in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Neuroscience. 1997;80(4):1209–1224. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt CE. Ontogeny of autonomic regulation in late preterm infants born at 34-37 weeks postmenstrual age. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30(2):73–76. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson AK. Autonomic dysfunction in spinal cord injury: clinical presentation of symptoms and signs. Prog Brain Res. 2006;152:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52034-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Seo H, Yang C, Brunet JF, Kim KS. Noradrenergic-specific transcription of the dopamine beta-hydroxylase gene requires synergy of multiple cis-acting elements including at least two Phox2a-binding sites. J Neurosci. 1998;18(20):8247–8260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08247.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobel R, Holditch-Davis D. Thermoregulation and heat loss prevention after birth and during neonatal intensive-care unit stabilization of extremely low-birthweight infants. Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing: JOGNN / NAACOG. 2007;36(3):280–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerspetz KYH. Postnatal development of thermoregulation in laboratory mice. Helgolander wissenshaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen. 1966;14(1-4):559–571. [Google Scholar]

- Laptook AR, Watkinson M. Temperature management in the delivery room. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2008;13(6):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley MJ, Badoer E, Vivas L, Oldfield BJ. Comparison of c-fos expression in the lamina terminalis of conscious rats after intravenous or intracerebroventricular angiotensin. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37(2):131–137. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton P. Principles and Practices of Unbiased Stereology: An introduction for bioscientists. Baltimor: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mouton PR, Gokhale AM, Ward NL, West MJ. Stereological length estimation using spherical probes. J Microsc. 2002;206(Pt 1):54–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2002.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobuta H, Cilio MR, Danhaive O, Tsai HH, Tupal S, Chang SM, Murnen A, Kreitzer F, Bravo V, Czeisler C, Gokozan HN, Gygli P, Bush S, Weese-Mayer DE, Conklin B, Yee SP, Huang EJ, Gray PA, Rowitch D, Otero JJ. Dysregulation of locus coeruleus development in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Acta neuropathologica. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1441-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobuta H, Cilio MR, Danhaive O, Tsai H, Tupal S, Chang SM, Murnen A, Kreitzer F, Bravo V, Czeisler C, Gokozan H, Gygli P, Bush S, Weese-Mayer DE, Conklin B, Yee S, Huang EJ, Gray P, Rowitch D, Otero J. Dysregulation of locus coeruleus development in congenitcal central hypoventilation syndrome. Acta neuropathologica. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1441-0. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero J, Danhaive O, Cilio M, Huang E, Rowitch D. American Association of Neuropathologists, Inc 87th Annual Meeting. Vol. 70. Seattle, WA: 2011. A Six-Week Old Male With Haddad Syndrome: Clinical, Genetic, and Pathological Evaluation; pp. 498–549. [Google Scholar]

- Otero JJ, Kalaszczynska I, Michowski W, Wong M, Gygli PE, Gokozan HN, Griveau A, Odajima J, Czeisler C, Catacutan FP, Murnen A, Schuller U, Sicinski P, Rowitch D. Cerebellar cortical lamination and foliation require cyclin A2. Dev Biol. 2014;385(2):328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangestiningsih TW, Hendrickson A, Sigit K, Sajuthi D, Nurhidayat, Bowden DM. Development of the area postrema: an immunohistochemical study in the macaque. Brain Res. 2009;1280:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn A, Morin X, Cremer H, Goridis C, Brunet JF. Expression and interactions of the two closely related homeobox genes Phox2a and Phox2b during neurogenesis. Development. 1997;124(20):4065–4075. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn A, Morin X, Cremer H, Goridis C, Brunet JF. The homeobox gene Phox2b is essential for the development of autonomic neural crest derivatives. Nature. 1999;399(6734):366–370. doi: 10.1038/20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Hoyda TD, Ferguson AV. The area postrema: a brain monitor and integrator of systemic autonomic state. Neuroscientist. 2008;14(2):182–194. doi: 10.1177/1073858407311100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MM, Williams KW, Rossi J, Lee CE, Elmquist JK. Leptin receptor expression in hindbrain Glp-1 neurons regulates food intake and energy balance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2413–2421. doi: 10.1172/JCI43703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler CM, Gozal D, Shea SA. Chemoreceptive mechanisms elucidated by studies of congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Respir Physiol. 2001;129(1-2):247–255. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan M, Bongianni F, Fontana GA, Pantaleo T. Respiratory responses to electrical and chemical stimulation of the area postrema in the rabbit. J Physiol. 1993;463:409–420. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M, Junghans D, Geissen M, Goridis C, Ernsberger U, Rohrer H. The Phox2 homeodomain proteins are sufficient to promote the development of sympathetic neurons. Development. 1999;126(18):4087–4094. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.18.4087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Moreira TS, Takakura AC, Kang BJ, Chang DA, West GH, Brunet JF, Mulkey DK, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Expression of Phox2b by brainstem neurons involved in chemosensory integration in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 2006;26(40):10305–10314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2917-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson DJ, Zellmer E, Lewis EJ. The homeodomain protein Arix interacts synergistically with cyclic AMP to regulate expression of neurotransmitter biosynthetic genes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(43):27382–27392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W, Pagliardini S, Yang P, Janczewski WA, Feldman JL. Projections of preBotzinger complex neurons in adult rats. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(10):1862–1878. doi: 10.1002/cne.22308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teppema LJ, Veening JG, Kranenburg A, Dahan A, Berkenbosch A, Olievier C. Expression of c-fos in the rat brainstem after exposure to hypoxia and to normoxic and hyperoxic hypercapnia. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388(2):169–190. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971117)388:2<169::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiveron MC, Hirsch MR, Brunet JF. The expression pattern of the transcription factor Phox2 delineates synaptic pathways of the autonomic nervous system. J Neurosci. 1996;16(23):7649–7660. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07649.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weese-Mayer DE, Berry-Kravis EM, Zhou L. Adult identified with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome--mutation in PHOX2b gene and late-onset CHS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(1):88. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.171.1.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Kim HS, Seo H, Kim CH, Brunet JF, Kim KS. Paired-like homeodomain proteins, Phox2a and Phox2b, are responsible for noradrenergic cell-specific transcription of the dopamine beta-hydroxylase gene. J Neurochem. 1998;71(5):1813–1826. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71051813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]