Abstract

Background

The transcription factor PLZF is transiently expressed during the development of ILC2s but is not present at the mature stage. We hypothesized that PLZF-deficient ILC2s have functional defects in the innate allergic response and represent a tool for studying innate immunity in a mouse with a functional adaptive immune response.

Objective

We determined the consequences of PLZF deficiency on ILC2 function in response to innate and adaptive immune stimuli using PLZF−/− mice and mixed WT:PLZF−/− bone marrow chimeras.

Methods

To induce innate type 2 allergic responses, PLZF−/− mice, WT littermates, or mixed bone marrow chimeras were treated with the protease allergen papain, the cytokines IL-25 and IL-33, or infected with the helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. To induce adaptive Th2 responses, mice were sensitized with intraperitoneal ovalbumin-alum, followed by intranasal challenge with ovalbumin alone. Lungs were analyzed for immune cell subsets and alveolar lavage fluid was analyzed for ILC2-derived cytokines. In addition, ILC2s were stimulated ex vivo for their capacity to release type 2 cytokines.

Results

PLZF-deficient lung ILC2s exhibit a cell-intrinsic defect in the secretion of IL-5 and IL-13 in response to innate stimuli, resulting in defective recruitment of eosinophils and goblet cell hyperplasia. In contrast, the adaptive allergic inflammatory response to ovalbumin and alum was unimpaired.

Conclusions

PLZF expression at the ILC precursor stage has a long-range effect on the functional properties of mature ILC2s and highlights the importance of these cells for innate allergic responses in otherwise immunocompetent mice.

Keywords: Allergic mechanisms, innate lymphoid cells, mouse models

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, an important role has emerged for lymphoid lineage cells with innate properties, such as innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), innate-like γδ-T cells, and invariant natural killer T cells (iNKTs) (1–5). ILCs develop from the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) via an ILC precursor in the bone marrow, while iNKTs and γδ-T cells are derived from the CLP but require thymic selection, albeit with a limited T-cell receptor repertoire. Lymphoid-derived innate cells serve to exert and promote early defense to pathogens and allergens, as well as repair and regeneration at mucosal barriers. They also provide a link with adaptive responses in the setting of infection, allergies, and autoimmune disease.

In studying the development of innate-like iNKT cells, we identified the transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein (PLZF) as a master regulator of this lineage and other distinct innate-like cells. Mice lacking the gene for PLZF have markedly reduced numbers of iNKTs, and the few remaining iNKTs have a naïve rather than effector phenotype, whereas forced expression of PLZF in T cells induced an effector phenotype (6, 7). Using a transgenic mouse that expresses a GFP-Cre fusion protein under control of the endogenous PLZF gene, we observed that PLZF was also expressed by a newly identified common precursor to ILCs, although expression was subsequently downregulated in mature ILC1, ILC2 and ILC3 (8). While the frequency of ILCs was not altered in PLZF-deficient mice, it was markedly decreased in mixed bone marrow chimeras where the mutant cells competed with the wild types. Thus, the current study was aimed at evaluating potential functional defects in PLZF-deficient ILC2s.

We focused on the pulmonary ILC2-dependent innate type 2 inflammatory response in mice lacking PLZF. Pulmonary ILC2s respond to cytokines (TSLP, IL-25 or IL-33) that are generated in the setting of helminth infection, viral infection, or inhalation of protease allergens, like papain (9–11). Upon stimulation, ILC2s can release large amounts of the type 2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13, which in turn promote the recruitment of eosinophils to the lung, airway hyperreactivity, mucous secretion, and airway smooth muscle thickening (12–14). Most published reports have used Rag1-deficient mice depleted of ILCs or Rag2−/−IL2rg−/− mice reconstituted with ILCs, and the exact role of ILC2s in non-immunocompromised mice has not been well studied (9, 11). We found that PLZF−/− mice manifested a markedly impaired response to various innate type 2 inflammatory stimuli due to cell-intrinsic defects in ILC2 function. However, adaptive Th2 responses remained intact. These data indicate that PLZF specifically controls the effector phenotype of ILC2s, and suggest that the PLZF−/− mouse is the first of its kind to have a functionally impaired innate lymphoid response but maintain an adaptive lymphocyte response.

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6J, CD1d−/− and CD45.1 congenic mice (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ) on the C57BL/6 background were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Plzf−/− mice were a gift from P. P. Pandolfi and were backcrossed to C57BL/6J for at least ten generations. Animals were 4–10 weeks of age when analyzed and were compared to WT littermate controls. Mice were housed in a specific-pathogen-free environment at the University of Chicago and experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Induction of Type 2 Innate Immune Responses

To induce type 2 immune responses, either papain (Calbiochem), IL-25 (eBiosciences) or IL-33 (eBiosciences) in PBS with carrier protein was administered intranasally on Day 1, 2, and 3 to the anesthetized mice, followed by harvest and analysis on Day 4. As controls, PBS or heat-inactivated papain was used. For infection with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, 500 L3 larva were resuspended in 200 μL sterile PBS according to published protocols and injected intradermally into 6–8 week old mice (15). On day 5 following infection, the mice were sacrificed for analysis.

Bronchoalveolar lavage

Mice were anaesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and immobilized. The trachea was cannulated using a 20-gauge blunt end catheter and 800 μL of cold PBS was slowly infused into the lungs, and withdrawn. This was repeated a total of 3 of times, yielding approximately 2 mL of recovered saline per mouse. These samples were immediately centrifuged at 400g for 5 minutes to pellet alveolar cells. The supernatants were removed and frozen at −20°C for subsequent cytokine analysis, while the cells were resuspended in HBSS containing 0.25% BSA and 0.65 mg l−1 sodium azide for subsequent flow cytometry analysis.

Preparation of cell suspensions

For the isolation of lung leukocytes, mice were anaesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and approximately 1 ml of PBS (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the right ventricle to perfuse the lung tissue. Pairs of lungs were diced and incubated in 5 ml of pre-warmed RPMI 1640 (Cellgro) containing 0.01% DNase I (Roche), and 650 units per ml collagenase I (Worthington) in a 37°C shaking incubator for 30 min. The digested tissue was passed through a 70 μm filter, washed with 25 mL of RPMI/10% FCS, and centrifuged at 400g for 5 min. The cells were resuspended in 5 ml of 44% Percoll, underlaid with 3 ml of 66% Percoll, and centrifuged at 800g for 20 min with no brake. Lymphocytes were isolated from the interface, washed, and resuspended in HBSS containing 0.25% BSA and 0.65 mg l−1 sodium azide for subsequent flow cytometry.

Microscopy

For histology, lungs were perfused through a needle inserted in the right ventricle with cold PBS in situ before removal and fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (histological grade; Thermo Fischer Scientific) under a vacuum overnight and then transferred to PBS for 24 h at 4°C. Lobes were sectioned sagittally, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm sections before staining with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). Histology micrographs were taken with the FSX-100 microscope camera system (Olympus). Data were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Flow Cytometry

Cell suspensions were incubated with purified anti-CD16/32 (clone 93) for 10 min on ice to block Fc receptors. Fluorochrome- or biotin-labeled monoclonal antibodies (clones denoted in parenthesis) against B220 (RA3-6B2), CD3ε (17A2), CD4 (RM4-5 or GK1.5), CD8α (53–6.7), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418), CD19 (6D5), CD25 (PC61), CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), ICOS (C398.4A), IL-7Rα/CD127 (A7R34), NK1.1 (PK136), Sca-1 (D7), Siglec-F (E50-2440), T1/ST2 (D1H9), TCRβ (H57-597), Thy1.2/CD90.2 (53–2.1), IL-5 (TRFK5), and IL-13 (JES-105A2) were purchased from BD Biosciences, BioLegend, eBioscience or R&D Systems. CD1d-PBS57 tetramer was from the NIH tetramer facility. To exclude dead cells, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Molecular Probes) was added to all live samples. Cells were run on an LSRII (BD Biosciences) or sorted using a FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Collected events were gated on DAPI−, CD45+ leukocytes, and doublets were excluded.

Lung ILC2s were identified as lineage− (B220, CD3ε, CD8α, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, Gr-1, NK1.1, TCRβ), and positive for IL-7Rα, Thy1.2, ICOS, Sca-1, and CD25. Eosinophils were gated as Siglec F+, CD11b+, CD11c−, SSChigh. Alveolar macrophages were identified as Siglec F+, CD11c+, autofluorescent on the FITC channel, CD11blow, FSChigh, and SSChigh. CD4+ T cells were identified as TCRβ+, CD4+, CD8− and B220−. CD8 T cells were identified as TCRβ+, CD4−, CD8+ and B220−. B cells were identified as B220+, TCRβ −. iNKT cells were identified as TCRβ+, tetramer+, CD8− and B220−.

For the isolation of lung ILC2, lung leukocytes were stained with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD25 antibody, bound to anti-APC microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), and subjected to double-column enrichment on an autoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec). CD25+ fraction was then sorted using the strategy described above for identifying lung ILC2s.

For intracellular cytokine staining, lung leukocytes were isolated and incubated with PMA (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (1 mM) for 3 hours at 37°C in the presence of 1 mM Brefeldin A (BD Biosciences). Non-adherent cells were then stained for identification of lung ILC2s as noted above, followed by fixation and intracellular staining with the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit. As a control, unlabeled anti-IL-5 or anti-IL-13 antibody was pre-incubated with the cells at a 25-fold excess to allow setting for positive and negative gates.

For measurement of cytokine concentration in the alveolar lavage fluid, the BD Cytometric Bead Array was used, analyzing for levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IFN-γ. Samples were analyzed in duplicate.

Cytokine production assay

Flow cytometry-purified PLZF−/− or WT littermate lung ILC2s were cultured in 200 ml RPMI-1640 media containing 10% FBS, penicillin and streptomycin (P/S), and 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (2ME) at 37°C. Cells were stimulated with IL-7 (10 ng/ml), and either IL-25 (10 ng/ml) or IL-33 (10 ng/ml) for 3 days. The extracellular media was then collected and analyzed for IL-5 and IL-13 by ELISA in triplicate (eBioscience).

Generation of mixed bone marrow chimeras

Recipient CD45.1/CD45.2+ mice were lethally irradiated with 1,000 Rads from a gamma cell 40 irradiator with a cesium source. Irradiated mice were injected i.v. with a mixture of bone marrow cells isolated from CD45.2+ PLZF−/− mice and CD45.1 WT congenic mice at a ratio of 2:1, favoring the PLZF−/− bone marrow. This ratio was chosen because of our observation that bone marrow from the PLZF−/− mice has fewer ILC2s, thus potentially biasing mixed chimera results in favor of wild type (unpublished observations). Cell numbers were then normalized to the splenic CD45.2:CD45.1 B cell ratios for each individual mouse, reflecting chimeric reconstitution. Mice were analyzed at least 6 weeks after reconstitution.

Sensitization and challenge with ovalbumin

PLZF−/−, WT littermates, and mixed bone marrow chimeras were treated using a 23-day model of sensitization and challenge for C57BL/6 mice, as previously described (16). Briefly, 50 μg ovalbumin (Sigma) was mixed with 50 μL Imject-alum (Thermoscientific) to a final volume of 100 μL and injected into each mouse intraperitoneally on days 0, 7, and 14. This was followed by a challenge phase, in which 100 μg of ovalbumin was delivered intranasally to anesthetized mice on days 20, 21, and 22, with sacrifice on day 23.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed Student’s t-test was performed using Prism (GraphPad Software) to determine whether data differed from the expected value. If the groups that were compared had significantly different variances (p < 0.05 by F test), Welch’s correction was applied. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01; ***P≤0.001

RESULTS

PLZF−/− mice treated with papain have a reduced type 2 inflammatory response

We treated PLZF−/− and PLZF+/+ WT littermates with papain intranasally (IN) for 3 days, prior to analysis of alveolar lavage and lung digests (Figure 1A). As shown in Figure 1B, PLZF−/− mice exhibited significantly less PAS-positive goblet cell hyperplasia, compared with PLZF+/+ WT mice, indicating an impairment in innate type 2 inflammation. Further, PLZF−/− mice exhibited a significantly decreased percentage of eosinophils in the lung digests (Figure 1C) in response to papain treatment. Importantly, recruitment of other type 2 inflammatory cell types (basophils, CD4 T cells, and ILC2s) was preserved in the PLZF−/− mice.

Figure 1. PLZF−/− mice have reduced type 2 inflammation in response to papain exposure.

A. Schematic for intranasal papain treatment of PLZF+/+ versus PLZF−/− littermate mice. B. Histology at 50X magnification of lungs treated as indicated, with counts of the percentage of PAS+ epithelial cells. C. Flow cytometry plots showing cell percentages within each plot, quantified cell counts, and quantified cell percentages in lung digests from mice treated as indicated for eosinophils (Siglec F+, CD11c−), basophils (Siglec F−, CD11c−, FcER1+, DX5+), ILC2s (lineage−, CD90+, ICOS+, Sca1+, CD25+, CD127+), and CD4+ T cells (CD19−, TCRβ+, CD4+). *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, *** p≤0.001. Experiments are pooled data from at least 2 separate experiments.

Type 2 inflammation is reduced in PLZF−/− mice treated with either inhaled IL-25 or IL-33 due to defective ILC2 function

Because papain administration activates ILC2s through the stimulation of IL-25 and IL-33 release from epithelial cells and macrophages, we studied type 2 pulmonary inflammation after IN administration of IL-25 or IL-33 (Figure 2A). As indicated in Figures 2B and 2C, PLZF−/− mice treated with 1 μg IL-25 IN or 0.1 μg IL-33 IN for 3 days showed markedly less eosinophilia and goblet cell hyperplasia compared with their WT counterparts. We measured the levels of IL-5 and IL-13 in the alveolar lavage fluid and found that PLZF−/− mice had lower amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 in response to either IL-25 or IL-33, reflecting the reduced type 2 inflammation in the lung (Figure 2D). Of note, with such a short stimulation in the absence of a specific adaptive response to a protein allergen, Th2 lymphocytes were not a significant source of IL-5 or IL-13, as assessed by intracellular cytokine staining (data not shown). To track the defect in cytokine secretion specifically to ILC2s, we sort-purified lung ILC2s and cultured them in vitro for 3 days with IL-7 and IL-33, or with PMA/Ionomycin, as described previously (9). IL-33 induced robust release of both IL-5 and IL-13 from WT ILC2s, while PLZF−/− ILC2s released significantly less IL-5 and IL-13 (Figure 2E). In addition, the response to ionomycin and PMA was markedly decreased in PLZF−/− ILC2s. Given the robust nature of the defect we observed to both IL-33 and PMA/ionomycin, we elected not to test responses to other cytokine combinations previously used to stimulate ILC2s in vitro (9, 17).

Figure 2. PLZF−/− mice have reduced type 2 inflammation and ILC2 activation in response to IL-25 or IL-33 inhalation.

A. Schematic for intranasal IL-25 or IL-33 treatment of PLZF+/+ versus PLZF−/− mice. B and C. Histology at 50X magnification of lungs treated with IL-25 (B), or IL-33 (C) with counts of PAS+ epithelial cells, and flow cytometry plots and cell percentages of eosinophils (Siglec F+, CD11c−) in lung digests from mice treated as indicated. D. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from mice treated with the indicated stimuli for 3 days was tested for either IL-5 or IL-13 by cytometric bead array. Samples were tested in duplicate, with each experiment using at least 3 mice, repeated 2–3 times. E. Sort-purified ILC2s were treated for 3 days in media containing IL-7 and either PBS, IL-33, or PMA/ionomycin (P/I). Media was then collected and tested for levels of IL-5 and IL-13 by ELISA. Results represent pooled results from 4 different samples, repeated twice.

The impaired responses of the PLZF−/− mice to several innate type 2 stimuli indicated a global defect in ILC2 function which may be sufficient to explain the decreased allergic airway inflammation induced by papain. However, the PLZF−/− mouse also lacks iNKTs. We therefore tested the response to innate type 2 stimuli in CD1d−/− mice that lack iNKTs but do not have defects in any other hematopoietic lineages, such as ILC2s. CD1d−/− mice did not demonstrate a defect in eosinophilia in response to intranasal IL-25 or papain treatment compared with wild type littermates, indicating that, in contrast with ILC2s, iNKTs are dispensable for the pulmonary innate response to these stimuli (Supplemental Figure 1).

PLZF−/− mice infected with the helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis have reduced pulmonary eosinophilia

ILC2s play a critical role during the pulmonary phase of infection with the helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, leading to eosinophilia and helminth clearance (10, 18, 19). We therefore infected PLZF−/− mice or WT littermates with 500 L3 N. brasiliensis, followed by examination 5 days later to assess pulmonary eosinophilia. As shown in Figure 3A, we observed a significant decrease both in the percentage and in the total number of eosinophils recruited to the lungs in PLZF−/− mice, suggesting a defect in the acute response to helminth infection. Importantly, the percentages of basophils (Figure 3A), CD4+ T lymphocytes (Figure 3B), and ILC2s (Figure 3C) were not significantly altered in PLZF−/− mice. These results are consistent with defective eosinophil recruitment by functionally impaired ILC2s, similar to that seen with papain and inhaled IL-25 and IL-33.

Figure 3. PLZF−/− mice have an impaired response to infection with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis.

Flow cytometry plots, cell counts, and cell percentages from the lung digests of PLZF−/− mice and PLZF+/+ littermates 5 days after infection with 500 L3 Nippostrongylus brasiliensis for A. eosinophils (Siglec F+, CD11c−), basophils (Siglec F−, CD11c−, FcER1+, DX5+), B. ILC2s (lineage−, Thy1+, ICOS+, Sca1+, CD25+, CD127+), or C. CD4+ T cells (CD19−, TCRβ+, CD4+). Bars indicate the mean, data are pooled from 2 different experiments (2–4 mice/condition/experiment), which were repeated twice.

Mixed bone marrow chimeras reveal cell-intrinsic reconstitution and activation defects in PLZF−/− derived ILC2s

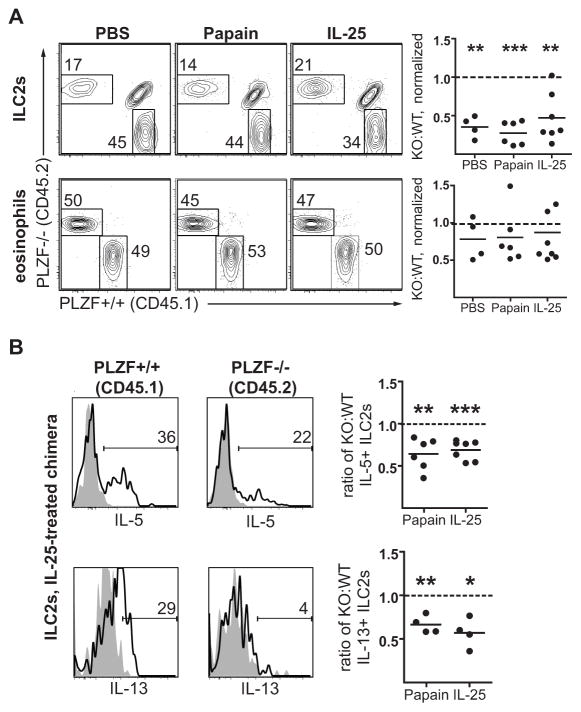

To prove further that the defects in the response of PLZF−/− mice were cell-intrinsic to ILC2s, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras using congenically labeled WT CD45.1 bone marrow mixed with PLZF−/− CD45.2 bone marrow into an irradiated CD45.1/CD45.2 recipient. This approach allows us to establish if PLZF−/− ILC2s are equally capable of reconstituting the ILC2 compartment in the lungs compared with their PLZF+/+ counterparts, and to examine the specific activation of PLZF−/− ILC2s relative to the PLZF+/+ ILC2s in response to stimulation. At 6 weeks after reconstitution, these chimeras were treated for 3 days with PBS, papain, or IL-25 to induce type 2 inflammation, as described above. Consistent with prior results from our lab, reconstitution of PLZF−/− ILC2s in the lungs was substantially impaired at baseline compared with WT ILC2s, as shown in Figure 4A (8). Furthermore, these cell-intrinsic defects were not corrected after inflammation induced by IL-25 or papain treatment. Importantly, eosinophil reconstitution, recruitment, and expansion were similar in the PLZF-deficient and sufficient compartments.

Figure 4. Mixed bone marrow chimeras reveal cell-intrinsic reconstitution and activation defects in ILC2s from PLZF−/− mice.

Mixed bone marrow chimeras were generated using CD45.1 PLZF+/+ (WT) and CD45.2 PLZF−/− (KO) bone marrow and, 6 weeks after reconstitution, treated for 3 days with papain, IL-25, or PBS intranasally, followed by analysis of lung digests. A. Flow cytometry plots and KO:WT ratios (normalized to splenic B cells) for ILC2s (CD25+, CD127+, Thy1+, ICOS+, lineage−) and eosinophils (Siglec F+, CD11c−). The dashed line indicates the predicted reconstitution ratio if no reconstitution defect were present. B. Flow cytometry histograms and quantitation of ILC2s from a representative IL-25-treated mixed chimera mouse comparing the percentage of CD45.2+, PLZF−/− ILC2s which are IL-5+ or IL-13+ (solid line) to CD45.1+, PLZF+/+ ILC2s. The negative control (filled grey) was derived by pre-incubating the ILC2s with excess unlabeled anti-cytokine antibody prior to staining with the indicated anti-cytokine antibody. Quantitation plots represent the ratio of CD45.2+, PLZF−/−, cytokine-positive ILC2s to CD45.1+, PLZF+/+, cytokine-positive ILC2s for either papain or IL-25 treatment. The dashed line indicates the predicted ratio if no activation defect were present. Experiments were repeated 2–3 times with 4–6 mice per condition. Statistical analysis with student’s t test for variation from a predicted ratio of 1.

We then compared intracellular IL-5 and IL-13 staining between WT and PLZF-deficient ILC2 in these chimeras. Histograms in Figure 4B show a representative sample of ILC2s from the lungs of a mixed chimera mouse treated with IL-25 for 3 days stained for either IL-5 or IL-13. Of note, radiation-resistant, CD45.1/CD45.2 double-positive ILC2s were excluded from this analysis. A smaller percentage of CD45.2+, PLZF−/− ILC2s stained positive for IL-5 or IL-13 compared with CD45.1+, PLZF+/+ ILC2s. To account for the ILC2 reconstitution defect noted in Figure 4A, the ratio of cytokine-positive KO:WT ILC2s was expressed relative to the total ratio of KO:WT ILC2s. If there were no defect in activation of IL-5 or IL-13 in PLZF−/− derived ILC2s, the ratio of PLZF−/−:WT ILC2s in the cytokine-positive population would have been identical to that of the total ILC2 population, or 1. However, the quantitation plots in Figure 4B reveal a significant activation defect in PLZF−/− ILC2s in response to either papain or IL-25 treatment for both IL-5 and IL-13 expression. Thus, the data establish the cell-intrinsic nature of the ILC2 functional defects and suggest that defective eosinophilia in papain or IL-25 treated PLZF−/− mice is secondary to impaired ILC2 effector function.

PLZF−/− T cells are capable of mediating Th2 responses to ovalbumin in both PLZF−/− mice and mixed bone marrow chimeras

Whether ILC2s can also control Th2 responses triggered by injection of antigen with alum has not been investigated. WT or PLZF−/− mice were sensitized with ovalbumin+alum intraperitoneally on days 0, 7, and 14, followed by ovalbumin inhalation on days 20, 21, and 22 and sacrifice on day 23 (16). As shown in Figure 5A, there was no significant difference in the degree of eosinophilia or in recruitment of CD4+ T cells to the lungs of PLZF−/− mice compared with WT mice, indicating that this Th2 response is independent of ILC2s.

Figure 5. PLZF−/− mice generate normal adaptive Th2 responses to ovalbumin.

PLZF−/− or PLZF+/+ littermate mice were sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin. A. Flow cytometry plots and percentages of lung digests for eosinophils and CD4+ T cells, as indicated. Bars indicate the mean. Summary data are pooled from 2 separate experiments. B. Mixed bone marrow chimeras were generated using CD45.1 PLZF+/+ and CD45.2 PLZF−/− bone marrow and sensitized to ovalbumin as described above. Eosinophils, ILC2s, and CD4+ T cells were normalized to splenic B cell numbers and expressed as a ratio of CD45.2 PLZF−/− to CD45.1 PLZF+/+ to determine if there were cell intrinsic defects in cells participating in lung inflammation in response to ovalbumin. The dashed lines indicate the predicted PLZF−/−:PLZF+/+ ratio if no cell intrinsic defect were present. C. Flow cytometry plots of CD4+ T cells (CD4+, TCRβ+, CD8−, CD19−) from ova-sensitized mixed chimera mice challenged with ovalbumin, gated as either CD45.2 PLZF−/− vs CD45.1 PLZF+/+ or as IL-5+ vs IL-13+. The cytokine positive cells are then gated for CD45.2 PLZF−/− vs CD45.1 PLZF+/+. The quantitation plot shows the ratio of KO:WT IL-5+/IL-13+ CD4+ T cells to total CD4+ T cells, and the dashed line indicates the predicted ratio of KO:WT IL-5+/IL-13+ CD4+ T cells if no activation defect were present. Experiments were repeated 2–3 times with 4–6 mice per condition. Statistical analysis with student’s t test for variation from a ratio of 1.

To prove that PLZF-derived CD4+ T cells function comparably to WT in a competitive environment, independent of ILC2 function, we examined the Th2 response in mixed CD45.1+, WT:CD45.2+, PLZF−/− bone-marrow chimeras, as described above. Ovalbumin sensitization and challenge led to a marked allergic inflammatory response with significant pulmonary eosinophilia (Figure 5B). Analysis of the normalized ratios of PLZF−/− to WT-derived eosinophils again revealed no cell-intrinsic defect in reconstitution or expansion, while PLZF−/− ILC2s demonstrated a marked defect in reconstitution and expansion. Furthermore, analysis of PLZF−/−-derived CD4+ T cells revealed no defect in reconstitution or expansion.

PLZF is not expressed in T or B cells (with the exception of iNKTs), but to confirm that T cells derived from PLZF−/− bone marrow retain functionality in a mixed chimera, we stained lung digest lymphocytes for IL-5 and IL-13 (8). Comparison of the normalized ratio of cytokine-positive PLZF−/−:WT CD4+ T cells to total PLZF−/−:WT CD4+ T cells showed no defect in upregulation of cytokine expression among CD4+ T cells derived from PLZF−/− bone marrow, indicating a functionally intact adaptive immune response (Figure 5C).

DISCUSSION

An important limitation of previously published research on ILC2 function has been the need to use systems in which the endogenous immune system is significantly altered. Adoptive transfer of purified ILC2s into Rag2−/−IL2rg−/− mice proves that ILC2s can mediate innate responses, but these mice lack endogenous lymphoid immune cells and lymph nodes (9). Functional studies using antibody-based depletion of ILC2s in Rag1−/− mice are also hindered by the lack of a functional adaptive immune response (9, 11). Reconstitution of lethally irradiated mice with bone marrow from Rorasg/-sg mice (possessing a mutant form of retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha (RORα)) partly circumvents this limitation (13, 20). The resulting chimeras do not have a significant ILC2 compartment but do develop T cells. However, this approach is limited by the potential presence of radiation-resistant cells (including ILC2s, which we have observed) coupled with concerns about the function of the reconstituted immune system compared with that of the wild type, unirradiated mouse. As we have demonstrated in this work, the PLZF−/− mouse model does not depend on irradiation or reconstitution of immune-deficient mice, and therefore complements the published research on ILC2 function. In addition, the PLZF−/− mouse model is a novel tool for dissecting the role that lymphoid-derived innate cells play in an otherwise immunocompetent system.

This work also reveals a unique role for PLZF in establishing effector function of lymphoid lineage innate cells. ILCs develop from the CLP in the bone marrow, via an innate lymphoid cell precursor, and subsequently migrate to the periphery (8). In contrast, iNKTs undergo thymic selection prior to emigration and maturation in the periphery (6). In spite of these disparate developmental pathways, PLZF acts as a global master transcription factor in conferring an effector phenotype on both lymphoid-derived innate cell types. Our previous work suggested that the PLZF−/− mouse has a reduced number of ILC precursors in the bone marrow and we confirmed this defect using the bone marrow mixed chimera. However, the PLZF−/− mouse has a nearly normal number of ILC2s in the lung, indicating that PLZF expression is not required for development, in contrast to its effect on ILC2 function. This is consistent with our observation that residual immature ILC2 in PLZF−/− mice express high levels of CD62L and lower levels of ICOS compared with their wild-type counterparts, which will likely impact tissue targeting and recirculation. The precise transcriptional targets of PLZF expression are currently under investigation, but likely include effector cytokines and other tissue-targeting integrins. Furthermore, we are evaluating epigenetic changes induced by PLZF that define the unique capacity of PLZF to pattern these effector phenotypes. Ultimately, ILC2 lacking PLZF have a profound functional defect, even in the face of a relatively preserved cell frequency.

Our findings are supported by several recent publications on ILC2 function. Maazi et al recently reported that mice lacking ICOS have impaired type 2 inflammation in response to inhaled IL-33 (21). Given that we previously demonstrated reduced ICOS expression on ILC2s from PLZF−/− mice, this may partly explain the reduced functionality of PLZF−/− ILC2s (8). Huang et al have postulated the existence of distinct ILC2 subsets, termed inflammatory ILC2 (iILC2s, responsive to IL-25) and natural ILC2 (nILC2s, responsive to IL-33) (22). The diminished responsiveness observed in PLZF−/− ILC2s to both stimuli is consistent with PLZF expression at an early common progenitor stage for both iILC2s and nILC2s, rendering both subsets hypofunctional. Christianson et al recently reported a feed forward mechanism for type 2 inflammation in mouse lungs, in which IL-13 secretion from stimulated ILC2s induces additional IL-33 secretion from epithelial cells to augment the allergic inflammatory response (23). The decreased secretion of IL-13 from PLZF−/− ILC2s would lead to a diminished feed-forward signaling cascade and presumably render PLZF−/− mice less susceptible to induction of allergic airways disease. Papain-induced ILC2 activation also depends on IL-4 secretion from basophils; our in vitro and mixed chimera experiments confirm that the ILC2 defect is cell-intrinsic and not due to dysfunctional basophil function (24). However, PLZF−/− ILC2s may be hyporesponsive to basophil-derived IL-4, thereby further decreasing IL-5 and IL-13 expression.

While our data unambiguously demonstrate an important role for PLZF in determining the effector function of ILC2s, the molecular mechanism remains to be investigated. Nevertheless, this study reinforces the importance of PLZF expression during development of lymphoid-derived innate cells by defining a previously unrecognized functional role for PLZF, and suggests that PLZF represents a unique tool for dissecting the function of these innate cells in disease models.

Supplementary Material

Key Messages.

ILC2s from mice lacking the transcription factor PLZF have functional defects in response to various type 2 immune stimuli

ILC2s are not required for alum-ova adjuvanted Th2 responses in the lungs

PLZF−/− mice are a novel tool for studying innate immune responses in an otherwise immunocompetent mouse

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32 HL007605 (P.V.) and R01HL118092, R01AI038339 and AI108643 (A.B.) and the University of Chicago Digestive Research Core Center Grant P30DK42086.

We thank the past and present members of the Bendelac lab for productive discussion and David Leclerc and Ryan Duggan for help with cell sorting.

Abbreviations used

- CLP

common lymphoid progenitor

- ILC

innate lymphoid cell

- iNKT

invariant natural killer T cell

- IN

intranasal

- IP

intraperitoneal

- KO

knockout

- PAS

periodic acid-Schiff

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PLZF

promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger

- Th2

T helper cell, type 2

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brennan PJ, Brigl M, Brenner MB. Invariant natural killer T cells: an innate activation scheme linked to diverse effector functions. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13(2):101–17. doi: 10.1038/nri3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs A, Colonna M. Innate lymphoid cells in homeostasis, infection, chronic inflammation and tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29(6):581–7. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328365d339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vantourout P, Hayday A. Six-of-the-best: unique contributions of gammadelta T cells to immunology. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13(2):88–100. doi: 10.1038/nri3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Commensal microbiota and NKT cells in the control of inflammatory diseases at mucosal surfaces. Current opinion in immunology. 2013;25(6):690–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantinides MG, Bendelac A. Transcriptional regulation of the NKT cell lineage. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25(2):161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savage AK, Constantinides MG, Han J, Picard D, Martin E, Li B, et al. The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity. 2008;29(3):391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Constantinides MG, McDonald BD, Verhoef PA, Bendelac A. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2014;508(7496):397–401. doi: 10.1038/nature13047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 2012;36(3):451–63. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price AE, Liang HE, Sullivan BM, Reinhardt RL, Eisley CJ, Erle DJ, et al. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(25):11489–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, Doering TA, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(11):1045–54. doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scanlon ST, McKenzie AN. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells: new players in asthma and allergy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halim TY, Steer CA, Matha L, Gold MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez I, McNagny KM, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40(3):425–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drake LY, Iijima K, Kita H. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4+ T cells cooperate to mediate type 2 immune response in mice. Allergy. 2014;69(10):1300–7. doi: 10.1111/all.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camberis M, Le Gros G, Urban J., Jr . Animal model of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and Heligmosomoides polygyrus. In: Coligan John E, et al., editors. Current protocols in immunology. Unit 19. Chapter 19. 2003. p. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caceres AI, Brackmann M, Elia MD, Bessac BF, del Camino D, D’Amours M, et al. A sensory neuronal ion channel essential for airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in asthma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(22):9099–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900591106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartemes KR, Kephart GM, Fox SJ, Kita H. Enhanced innate type 2 immune response in peripheral blood from patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(3):671–8. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner JE, Morrison PJ, Wilhelm C, Wilson M, Ahlfors H, Renauld JC, et al. IL-9-mediated survival of type 2 innate lymphoid cells promotes damage control in helminth-induced lung inflammation. J Exp Med. 2013;210(13):2951–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung LY, Lewkowich IP, Dawson LA, Downey J, Yang Y, Smith DE, et al. IL-33 drives biphasic IL-13 production for noncanonical Type 2 immunity against hookworms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(1):282–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206587110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halim TY, Maclaren A, Romanish MT, Gold MJ, McNagny KM, Takei F. Retinoic-Acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37(3):463–74. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maazi H, Patel N, Sankaranarayanan I, Suzuki Y, Rigas D, Soroosh P, et al. ICOS:ICOS-Ligand Interaction Is Required for Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Function, Homeostasis, and Induction of Airway Hyperreactivity. Immunity. 2015;42(3):538–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y, Guo L, Qiu J, Chen X, Hu-Li J, Siebenlist U, et al. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential ‘inflammatory’ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(2):161–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christianson CA, Goplen NP, Zafar I, Irvin C, Good JT, Jr, Rollins DR, et al. Persistence of asthma requires multiple feedback circuits involving type 2 innate lymphoid cells and IL-33. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motomura Y, Morita H, Moro K, Nakae S, Artis D, Endo TA, et al. Basophil-derived interleukin-4 controls the function of natural helper cells, a member of ILC2s, in lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40(5):758–71. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.