Abstract

Background

Patients with asthma are highly susceptible to air pollution and in particular, to the effects of ozone (O3) inhalation, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

Objective

Using mouse models of O3-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness (AHR), we sought to investigate the role of the recently discovered group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2).

Methods

C57BL/6 and Balb/c mice were exposed to Aspergillus fumigatus and/or O3 (2ppm, 2h). ILC2 were isolated by FACS sorting and studied for IL-5 and IL-13 mRNA expression. ILC2 were depleted with anti-Thy1.2 mAb and replaced by intratracheal transfer of ex vivo expanded Thy1.1 ILC2. Cytokines (ELISA, qPCR), inflammatory cell profile and AHR (FlexiVent) were assessed in the mice.

Results

In addition to neutrophil influx, O3 inhalation elicited the appearance of eosinophils and IL-5 in the airways of Balb/c but not C57BL/6 mice. Although O3 induced expression of IL-33, a known activator of ILC2 in the lung was similar between these strains, isolated pulmonary ILC2 from O3 exposed Balb/c mice had significantly greater IL-5 and IL-13 mRNA expression than those of C57BL/6 mice. This suggested that an altered ILC2 function in Balb/c mice may mediate the increased O3 responsiveness. Indeed, anti-Thy1.2 treatment abolished, whereas ILC2 add-back dramatically enhanced O3-induced AHR.

Conclusions

O3-induced activation of pulmonary ILC2 was necessary and sufficient to mediate asthma-like changes in Balb/c mice. This previously unrecognized role of ILC2 may help explain the heightened susceptibility of human asthmatic airways to O3 exposure.

Keywords: ozone, group-2 innate lymphoid cells, airway hyperresponsiveness

INTRODUCTION

With the emergence of heavily polluted megacities, exposure to the common air pollutant ozone (O3) is a global respiratory health problem. O3 is an important trigger of asthma exacerbation1–3 but the underlying pathways remain unclear. The O3-induced inflammatory changes occur acutely and the clinical symptoms can last up to a week in asthmatic patients4. The O3 effects involve activation of the pulmonary epithelium and innate immune system, with release of IL-6 and IL-8 followed by influx of neutrophilic granulocytes. In asthmatic patients5, 6 and in mouse models of allergic airway inflammation7 O3 also elicited IL-5 release within hours of exposure. IL-5 is classically considered to be one of the T helper type 2 (Th2) cell derived cytokines released together with IL-4 and is responsible for eliciting airway eosinophilia, a cardinal pathologic feature of asthma8, 9. In our previous studies IL-5 appeared without detectable levels of IL-4 in the airways within a few hours of O3 exposure7, suggesting an early source of IL-5 during the inflammatory airway response, distinct from Th2 cells.

Lung resident group-2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2)10 are recently described innate lymphocytes with a capability to release IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-33 without antigenic stimulation, and to initiate and perpetuate allergic airway inflammation. ILC2 reside in adipose tissues and at various barrier mucosal sites in the intestine and lung. During influenza virus infection ILC2 accumulate and mediate virus-induced AHR as well as epithelial repair11, 12. Lung ILC2 also promote acute airway eosinophilia in mice exposed to the protease papain or the fungal allergen Alternaria13–17. The function of ILC2 appears to be evolutionarily conserved, because human ILC2 also produce Th2 cytokines in response to IL-33 and IL-25 similarly to mouse ILC23, 11, 18, 19. We hypothesized that activation of lung resident ILC2 could contribute to the rapid inflammatory changes elicited by O3 exposure in mice.

METHODS

Mice

All experimental animals used in this study were housed under pathogen free conditions. Experiments were performed on male mice between 8 and 12 weeks of age. Animals received water and food ad libitum. C57BL/6, Balb/c, and Thy1.1 mice were purchased from the National Institutes of Health and the Jackson Laboratory. Bicistronic IL-4 reporter (4get) mice20 were the gift of Dr. Kerry Campbell (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA) and were bred in house. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania.

O3 exposure and allergen challenge protocols

Allergen sensitization/challenge and O3 exposure have been carried out as before7. Briefly, mice were sensitized with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of 20 µg Aspergillus fumigatus (Af) mixed with alum on day 0 and 7 and received an intranasal challenge with 25µg of Af on day 13. Mice were exposed to air or O3 (2 ppm) or to forced air for 2 hours on Day 16 and were sacrificed 12h after O3 exposure on Day 17. When mice were exposed to O3 or forced air alone, unless otherwise indicated, they were studied 12 hours after the exposure ended. This time point was selected based on pilot time course studies, to represent the height of proinflammatory changes as seen in Balb/c mice. The chosen level of ozone exposure in our studies was based on numerous previously published works on mice, rats and humans by other laboratories and ours. The 2ppm O3 dose represents a level of exposure that is well tolerated by both Balb/c and C56BL/6 mice and that causes a significant airway inflammatory response. That a 2ppm inhaled dose in rodents results in O3 concentration in the lungs relevant to human exposure levels has been experimentally also validated by others, using oxygen-18-labeled O3 (18O3). For example, in a study by Hatch et al. it was demonstrated that exposure to 18O3 (0.4 ppm for 2 h) caused four- to fivefold higher 18O3 concentrations in humans than in rats21. Rats exposed to 2.0 ppm, had still less 18O3 in BAL than humans (exposed to 0.4 ppm). The species discrepancies between the recoverable O3 levels in the lung are not entirely clear but Slade et al. demonstrated that after exposure to O3, mice react by a rapid decrease of core temperature, a species and strain specific characteristics22. The recoverable 18O3 in the lung tissue was negatively associated with the extent of hypothermia that significantly altered O2 consumption and pulmonary ventilation, explaining at least partly, the interspecies differences seen in O3 susceptibility.

BAL was performed and cells were assessed on cytospin preparations stained with DiffKwik. Mice were compared for total and differential BAL cell counts, using a Countess® Automated Cell Counter and Cytospin counts. In other experiments BAL was also processed for FACS analysis. Lungs were perfused and removed for isolation of ILC2 cells and RNA extraction. The BAL supernatant was processed for ELISA for IL-4 and IL-5 expression.

Immunoglobulin treatment, isolation of lung hematopoietic cells and adoptive transfer

To deplete ILC2 cells, 4 doses of anti-Thy1.2 mAb (30H12, West Lebanon), and anti-CD4 mAb (GK1.5, BD bioscience) were administered intraperitoneally every other day (0.5 mg/mouse). For FACS analysis and ILC2 isolation mice were exsanguinated and lungs were perfused by injecting 10 ml PBS into the right ventricle of the heart. Lungs were carefully cut into small fragments and digested in Hank’s balanced salt solution containing 0.025 mg/ml Liberase D (Roche Diagnostics) and 10 U/ml DNase I (Roche Diagnostics). Cells were filtered by using a cell strainer. For adoptive transfer, lung ILC2 were isolated from Thy1.1 mice by FACS sorting, and grown with IL-2, IL-7, IL-33 for 7 days. 106 cells were intratracheally transferred into anti- Thy1.2 mAb treated Thy1.2 mice.

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

Antibodies were purchased from eBioscience unless specified otherwise. The anti-lineage (Lin) mixture included anti-FcεR (MAR-1), anti-B200 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD19 (ID3), anti-Mac-1 (M1/70), anti-Gr-1 (8C5), anti-CD11c (HL3), anti-NK1.1 (PK 136), anti-Ter-119 (Ter-119), anti-CD3 (2C11), anti-CD8b (53.5.8), anti-TCRb (H57), and anti-gdTCR (GL-3). We also used anti-Thy1.2 (53-2.1), anti-Siglec F (E50-2440; BD Biosciences), and anti-ST2 (DJ8; MD Bioproducts). Cell sorting was performed on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences), and flow cytometric analysis was performed on a LSR-II (BD Biosciences).

Cytokine assessment

BAL IL-4 and IL-5 expression was measured by standard sandwich ELISA (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total mRNA and protein were extracted from perfused lung tissue. In the O3 time course experiments il33 mRNA was measured as part of an Affymetrix GeneChip® Microarray. IL-33 protein was assessed as part of a Luminex assay. For comparison of Balb/c and C57BL/6 lung il33 mRNA, lung tissue was obtained and total RNA extracted 12 h after air or O3 exposure and qPCR was performed. ILC2 and CD4 T cells were FACS sorted, total RNA extracted and cytokine mRNA expression was examined by qPCR.

Lung function measurements

Airway hyperresponsiveness to aerosolized acetyl-β-methylcholine chloride methacholine (MCh) inhalation was assessed using the FlexiVent system (SCIREQ, Montreal, Canada) as described before23. Briefly, lung mechanics were studied in tracheostomized mice under anesthesia by intra-peritoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine. Mice were ventilated with a tidal volume of 8ml/kg at a rate of 150 breaths/min and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 2cm H2O by a computerized FlexiVent System. After mechanical ventilation for 2 min, a sinusoidal 1-Hz oscillation was applied to the tracheal tube. The single-compartment model was fitted to these parameters by multiple linear regression to calculate dynamic resistance, compliance and tissue damping of the airway. Baseline measurements and responses to aerosolized saline were followed by measurements of responses to increasing doses of (0.625–25 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). Recorded values were averaged for each dose and used to obtain dose-response curves for each mouse.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as Mean±SEM. All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 Software, (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA). Multiple group comparisons were made using one way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni correction. Differences between groups in MCh responsiveness were assessed by two-way ANOVA.

RESULTS

Ozone exposure enhanced Aspergillus fumigatus induced eosinophilia in Balb/c, but not C57BL/6 mice

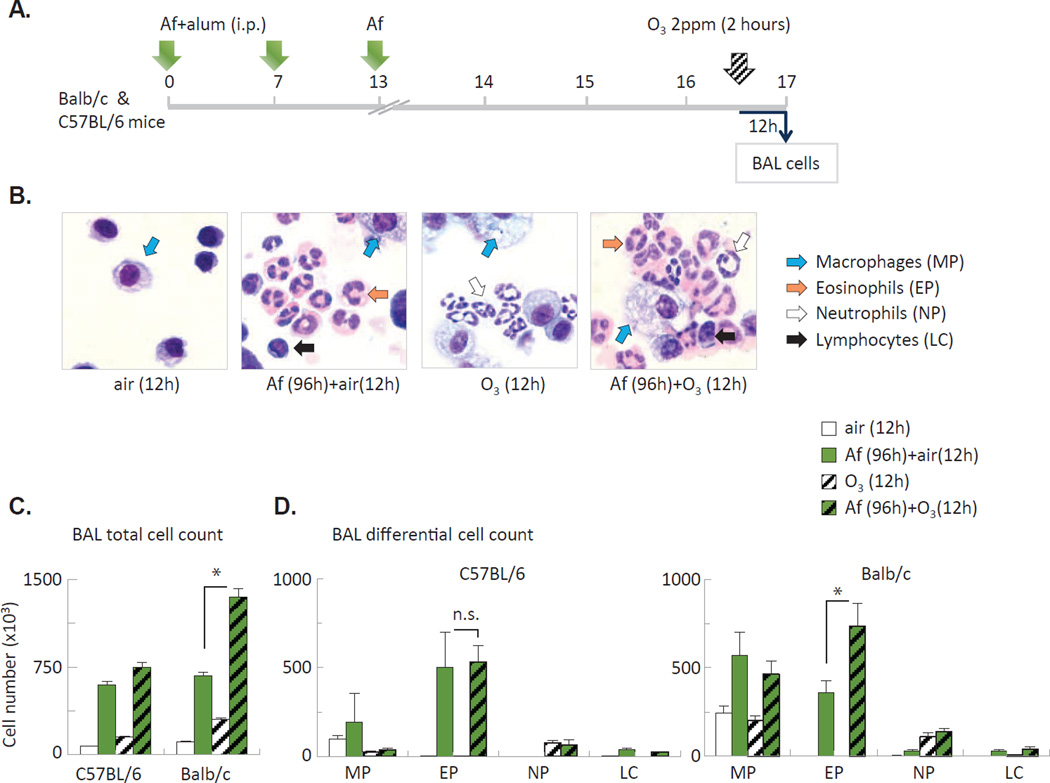

To model exacerbation of allergic airway changes (seen in asthmatic patients upon O3 inhalation), we used a combined allergen sensitization/challenge and O3 exposure protocol7. In this model mice were sensitized with intraperitoneal injections of Aspergillus fumigatus (Af) mixed with alum on day 0 and 7 and received an intranasal challenge with Af on day 13. Mice were exposed to O3 or to forced air for 2 hours on Day 16 and were sacrificed 12h later, on Day 17 (Figure 1A). Af induced eosinophilic airway inflammation, O3 induced airway neutrophilia, while the combination of these treatments elicited appearance of both eosinophils and neutrophils in the airways (Figure 1B). Quantitation of the changes revealed that in allergen-sensitized and challenged mice O3 virtually doubled the numbers of eosinophils in the BAL fluid of Balb/c mice but not in C57BL/6 mice (Figure 1C–D) indicating strain differences of the airway response.

Figure 1. O3 enhanced airway eosinophilia in allergen challenged Balb/c but not C57BL/6 mice.

(A) Combined allergen and O3 exposure protocol. (B) Representative cytospin preparations of BAL cells from Balb/c mice. (C–D) BAL total and differential cell counts from C57BL/6 and Balb/c mice. MP: macrophages; EP: eosinophils; NP: neutrophils; LC: lymphocytes. *p<0.05, Mean±SEM of n=3–9.

Ozone exposure induced IL-5 release and airway eosinophilia in Balb/c, but not C57BL/6 mice

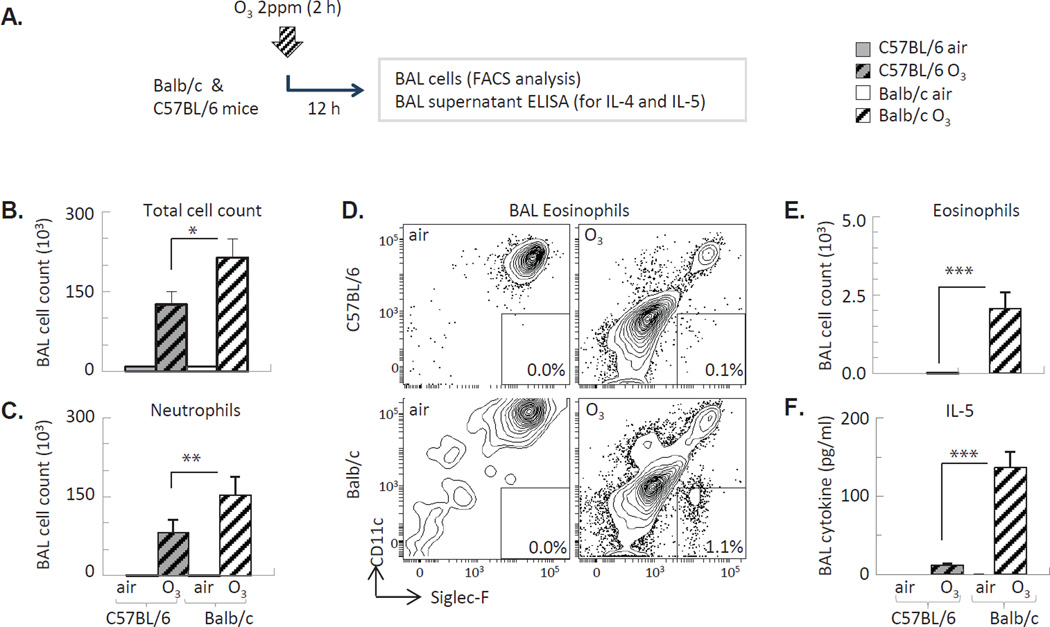

Balb/c mice have increased susceptibility to Th2-mediated inflammatory conditions in comparison with C57BL/6 mice24. To investigate whether Balb/c mice would respond to O3 differently without the priming effects of allergen sensitization and challenge, we further assessed these strains exposed to O3 alone (Figure 2A) and found that the total (Figure 2B) and neutrophil (Figure 2C) cell counts in the BAL were increased to a lesser extent in C57BL/6 than in Balb/c mice in response to O3. Further, in Balb/c but not C57BL/6 mice O3 inhalation resulted in an influx of a small but significant numbers of eosinophils in the BAL 12 h later (Figure 2D–E), together with increased IL-5 expression (Figure 2F). IL-5 release within the first 12 hours after O3 exposure occurred without increased numbers or activation of Th2 cells in the lung as indicated by lack of IL-4 release into the airways (not shown) or activation of the IL-4 gene promoter in the BAL cells of “4get” mice (not shown).

Figure 2. O3 exposure of Balb/c mice induced eosinophil influx and IL-5 release into the airways.

(A) Experimental design. (B) Total BAL cell counts (Countess®). (C, E) BAL neutrophils and eosinophils were quantified by FACS analysis. (D) Representative flow profile of Siglec F+ eonsinophils in the BAL. (F) IL-5 assessed from the BAL supernatant by ELISA *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (ANOVA with Bonferroni correction), Mean±SEM of n=3–5.

Ozone exposure activates lung-resident ILC2

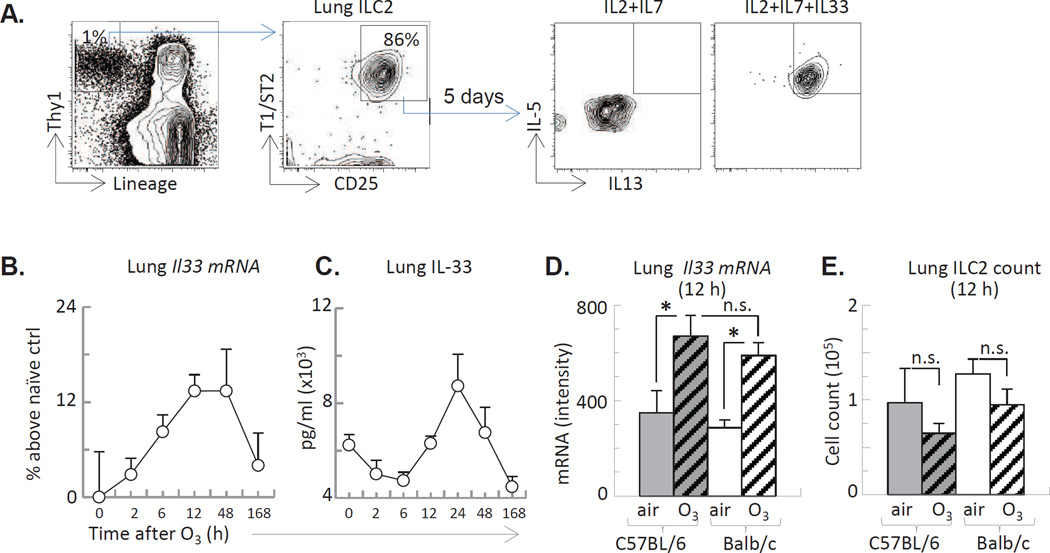

IL-5 was produced by isolated lung ILC2 in response to the addition of the epithelial derived cytokine, IL-33 (Figure 3A). O3 exposure of the mice induced IL-33 mRNA activation and increased protein expression in the lung tissue in a time dependent manner (Figure 3B–D Balb/c data are shown). The kinetics or extent of IL-33 expression were comparable between the two mouse strains (Figure 3D). The number of ILC2 remained similar between air and O3 exposed mice (Figure 3E) suggesting no ILC2 influx or proliferation within 12 h after O3 exposure.

Figure 3. O3 induced time dependent IL-33 expression in the lung.

(A): Lung ILC2 isolated by FACS sorting, stimulated in vitro with IL-33 for 5 days and assessed for IL-5 and IL-13 by FACS. (B–D): Balb/c mice exposed to O3 for 2 h and studied for lung IL-33 mRNA and protein expression at the indicated time points. (E): The number of lung-resident ILC2, assessed by FACS. *p<0.05; (ANOVA with Bonferroni correction), Mean±SEM of n=3–5 (n.s. not significant)

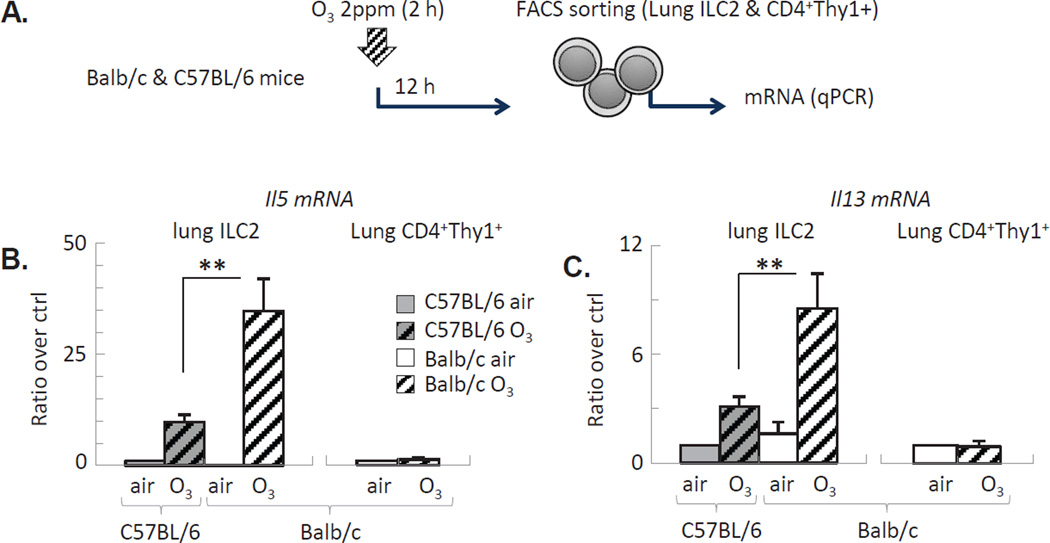

We have then isolated ILC2 from the lungs (Figure 4A) and studied them ex vivo. qPCR showed a significantly increased activation of IL-5 and IL-13 mRNA 12 h after O3 exposure (Figure 4B–C). This was evident in both strains. However, the effects were markedly greater in Balb/c ILC2 compared with C57BL/6 ILC2. O3 did not induce IL-5 or IL-13 production by CD4+ Thy1+ T helper cells isolated from the lungs 12 h after exposure, supporting that ILC2 but not T helper cells were the major source of these cytokines at this early time point following O3 inhalation.

Figure 4. O3 activated expression of IL-5 and IL-13 mRNA was enhanced in lung-resident ILC2 of Balb/c mice.

(A): Experimental design: Lung ILC2 and CD4+ T cells were isolated 12 h after O3 exposure and processed for qPCR analysis. (B–C): Il5 and Il13 mRNA of ILC2 and T cells was normalized to GAPDH. Mean±SEM of n=3; **p<0.01; (ANOVA with Bonferroni correction).

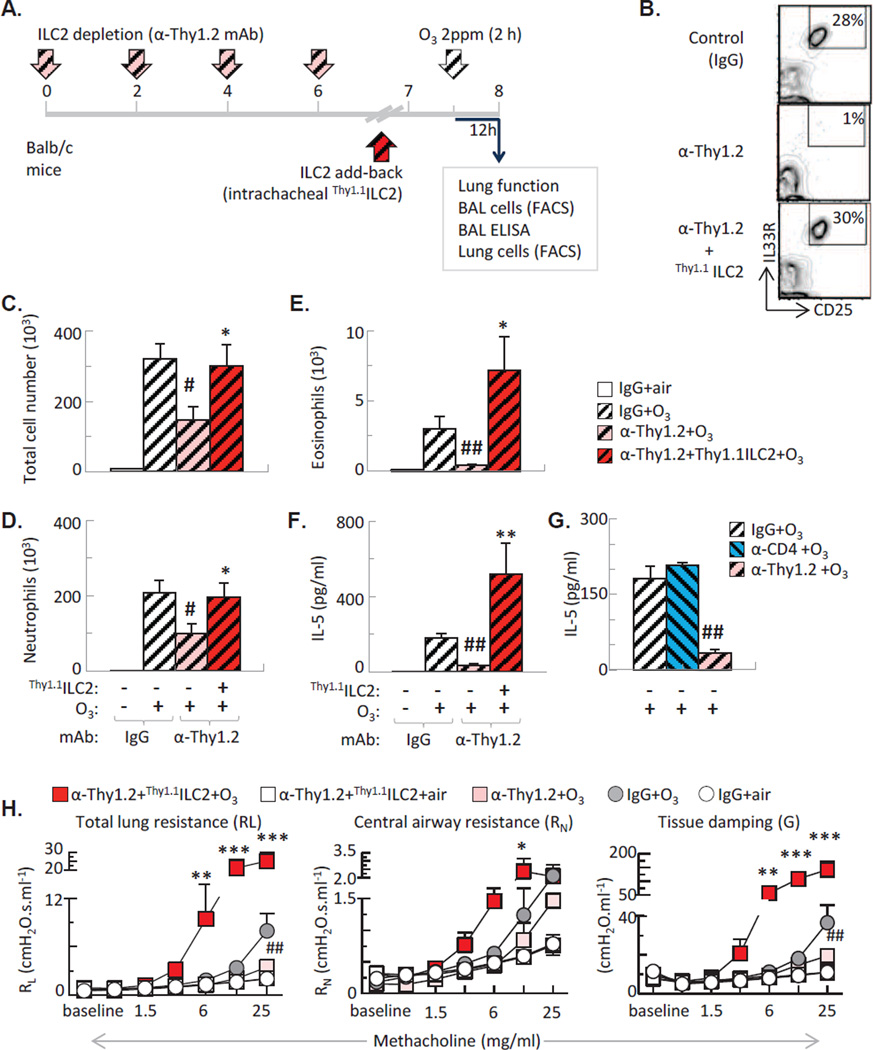

ILC2 mediate ozone-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness

To determine whether ILC2 activation in Balb/c mice is causally related to ozone induced airway inflammation, we treated mice with anti-Thy1.2 mAb (that depletes both innate lymphoid cells and T cells, Figure 5A, 5B), or anti-CD4 mAb (that specifically depletes CD4+ T helper cells). Anti-Thy1.2 mAb treatment significantly reduced total cell count and neutrophilia and abolished eosinophils in the BAL fluid of the O3 exposed Balb/c mice (Figure 5C–E). Anti-Thy1.2 treatment (Figure 5F–G), but not anti-CD4 mAb (Figure 5G), abolished IL-5 release in the BAL of O3 exposed mice, confirming that innate lymphoid cells but not T helper cells were likely the major source of IL-5, 12 h after exposure.

Figure 5. ILC2 was required for O3-induced airway inflammation and AHR.

(A): Experimental design: Balb/c mice received anti-thy1.2 (or control IgG) mAb. ILC2 were subsequently replaced by intratracheal transfer of Thy1.1 ILC2. (B): Representative flow plots indicating that the proportion of recovered ILC2 after transfer is commensurate with that of the non-depleted mice. (C–E): Anti-Thy1.2 mAb treatment inhibited, transfer of ILC2 increased lung total, neutrophil and eosinophil counts in O3 exposed Balb/c mice. (F): antiThy1.2 but not anti-CD4 attenuated IL-5 release into the airways. ILC2 replacement significantly enhanced IL-5 in response to O3. (G): Anti-Thy1.2 inhibited, ILC2 replacement significantly enhanced AHR after O3. Mean±SEM of n=8–9; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 vs. α-Thy1.2 +O3; #p<0.05; ##p<0.01; vs. IgG+O3 (ANOVA with Bonferroni correction).

Since anti-Thy1.2 mAb treatment depletes both ILC2 and T cells, we added back Thy1.1+ ILC2 by intratracheal transfer to verify the specific role of these cells in O3-induced airway inflammation (Figure 2A–B). We transferred ILC2 that were expanded in vitro with IL-2, IL-7 and IL-33. ILC2 transfer restored total and neutrophil cell count and significantly enhanced IL-5 and airway eosinophilia in response to O3 in anti-Thy1.2 mAb treated mice (Figure 2C–F).

To confirm if the ILC2 effects had any physiological relevance we investigated the lung function of the O3 exposed mice by studying their methacholine responsiveness (Figure H5). Anti-Thy1.2 mAb treatment (pink squares) significantly reduced AHR after O3 inhalation. Conversely, ILC2 transfer into the anti-Thy1.2 mAb treated mice (red squares), dramatically enhanced AHR to methacholine after O3. Notably, ILC2 transfer did not induce spontaneous AHR in air-exposed mice (white squares), suggesting that in vivo activation of these cells by O3 exposure is a requirement for the physiological effects.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we described a novel role of innate lymphoid cells in ozone-induced acute airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. We found that ozone exposure increased airway levels of IL-33, a potent activator of ILC2. We showed that lung-resident ILC2 were the predominant early source of Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 in ozone-exposed mice. Cell depletion and add-back experiments established an essential role of ILC2 in mediating ozone-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. Together, these data indicated that ILC2 are critical effector cells in O3-induced airway inflammation in mice.

The heightened sensitivity of asthma patients in comparison with healthy individuals, to air pollution, especially O3 inhalation is not well understood5, 25–27. In mouse models, allergen-28, 29 and O3-induced airway changes also vary among different strains7, 30 implying genetically determined pathologies. Here we mimicked exacerbation of allergic airway changes by O3 inhalation7 in allergen-sensitized and challenged mice. O3 virtually doubled the numbers of eosinophils in the BAL fluid of Balb/c but not in C57BL/6 mice confirming strain differences of the airway response. Indeed Balb/c mice responded to O3 inhalation differently from C57BL/6 mice even without the priming effects of allergen sensitization and challenge: In addition to the increased numbers of neutrophils, Balb/c mice had eosinophils, together with an increased IL-5 expression in the airways induced by O3. Although eosinophilia may be synergistically promoted by a number of chemokines, cytokines and growth factors (inducible by O37, 31, 32), presence of IL-5 is a prerequisite. Importantly, IL-5 expression within the first 12 hours after O3 exposure occurred without increased numbers or activation of Th2 cells in the lung as indicated by the lack of IL-4 release into the airways or activation of the IL-4 gene promoter in the BAL cells of “4get” mice, suggesting an alternative source of IL-5.

Besides Th2 cells, ILC2 can also produce IL-5 when stimulated by the epithelial derived cytokine, IL-3310, 12, 33. Interestingly, we found that O3 induced IL-33 expression in the lung in a time dependent manner. This effect was comparable between Balb/c and C57BL/6 mice. The number of ILC2 did not change after O3 exposure in either strains, suggesting that within the 12-hours time period, no ILC2 influx or proliferation took place in the lung. Notably however, when ILC2 were isolated from the lungs, their capability to express IL-5 and IL-13 mRNA was significantly increased. While both strains showed IL-5 and IL-13 mRNA induction, the effects were markedly greater in Balb/c ILC2 compared with C57BL/6 ILC2. Further, O3 did not induce IL-5 or IL-13 production by CD4+ cells confirming that ILC2 but not T helper cells were the major source of these cytokines at this early time point following O3 inhalation. These results established that in comparison with C57BL/6 mice, Balb/c mice exhibited increased airway neutrophilia, displayed evidence of eosinophil granulocytes in the airways and expressed heightened IL-5 levels in the BAL fluid after O3 inhalation. Such discrepancies in O3 responsiveness were associated with a markedly amplified activation of IL-5 and IL-13 mRNA in pulmonary ILC2 of Balb/c mice. Thus, O3 activated Balb/c ILC2 to a significantly greater extent than C57BL/6 ILC2 suggesting that ILC2 in these strains are intrinsically different in their function. It is possible therefore that ILC2 functional differences are also responsible to O3 susceptibility in asthmatic patients.

Although recent work has made significant advances in understanding the biology of ILC, their functional capability remains to be better appreciated. ILC2 activation can cause asthma-related features including airway inflammation, mucus production and AHR. To determine whether ILC2 activation in Balb/c mice is causally related to ozone induced airway inflammation, we depleted both innate lymphoid cells and T cells or specifically, CD4+ T helper cells. Depletion of ILC2 and T cells significantly reduced total cell counts and neutrophilia and abolished the presence of eosinophils in the BAL fluid of the O3 exposed Balb/c mice. ILC2 but not CD4 depletion abolished IL-5 release in the BAL of O3 exposed mice, confirming that the source of this cytokine were the ILC2. ILC2 add back restored total and neutrophil cell count and significantly enhanced IL-5 and airway eosinophilia in response to O3.

To investigate the physiological relevance of the ILC2 effects we investigated the lung function of the O3 exposed mice. Because we found that O3 heightened IL-13 induction in Balb/c ILC2 and because IL-13 can directly induce airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR)12, 34, 35, we hypothesized that presence of ILC2 in the lung is necessary for the O3-induced AHR. Indeed ILC2 depletion significantly reduced AHR after O3 inhalation while ILC2 add back dramatically enhanced AHR after O3. As ILC2 transfer did not induce spontaneous AHR in air-exposed mice, we propose that in vivo activation of these cells by O3 exposure is a requirement for the physiological effects.

Our data clearly demonstrated the effectiveness of activated ILC2 in altering lung physiology. The mechanism and significance of the direct ILC2 action on AHR in response to O3 will need further clarification. Nonetheless the facts that the O3 activated ILC2 outcomes were disproportionately greater on methacholine responsiveness than on airway inflammation and that ILC2 can affect AHR through IL-13 during inflammatory changes in the lung12, 35 suggest a potential direct regulatory role of these cells in airway physiology. In summary, we identified lung-resident ILC2 as the cell type responsible for airway inflammation induced by an air pollutant. Our study suggests that ILC2 may significantly contribute to the mechanisms by which air pollution induces asthma exacerbation.

KEY MESSAGES.

O3 induced release of IL-33 in the lung of mice.

Increased susceptibility of Balb/c mice to O3 induced inflammatory changes was associated with elevated production IL-5 and IL-13 of by pulmonary ILC2.

Depletion of ILC2 suppressed while repletion enhanced airway inflammatory changes induced by O3 inhalation in mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for Drs. Reynold A. Panettieri and David Artis (UPENN) for critical reading of the manuscript

Funding: R01AI072197(AH); RC1ES018505(AH); P30ES013508(AH); R21 AI059621(AB and AH), and AI098428 (AB).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- EP

eosinophil

- i.n.

intranasal

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.t.

intratracheal

- IL

interleukin

- ILC2

type 2 innate lymphoid cell

- LC

lymphocyte

- MP

macrophage

- NP

neutrophil

- O3

ozone

- ppm

parts per million

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- Th2

T helper type 2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ledford DK, Burks AW, Ballow M, Cox L, Wood RA, Casale TB. Statement regarding. "The public health benefits of air pollution control". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, Ewart G, Kraft M, Finn PW. The public health benefits of air pollution control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:22–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim KH, Jahan SA, Kabir E. A review on human health perspective of air pollution with respect to allergies and asthma. Environ Int. 2013;59:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peel JL, Tolbert PE, Klein M, Metzger KB, Flanders WD, Todd K, et al. Ambient air pollution and respiratory emergency department visits. Epidemiology. 2005;16:164–174. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000152905.42113.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosson J, Stenfors N, Bucht A, Helleday R, Pourazar J, Holgate ST, et al. Ozone-induced bronchial epithelial cytokine expression differs between healthy and asthmatic subjects. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:777–782. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frischer T, Studnicka M, Halmerbauer G, Horak F, Jr, Gartner C, Tauber E, et al. Ambient ozone exposure is associated with eosinophil activation in healthy children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1213–1219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kierstein S, Krytska K, Sharma S, Amrani Y, Salmon M, Panettieri RA, Jr, et al. Ozone inhalation induces exacerbation of eosinophilic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in allergen-sensitized mice. Allergy. 2008;63:438–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JJ, Dimina D, Macias MP, Ochkur SI, McGarry MP, O'Neill KR, et al. Defining a link with asthma in mice congenitally deficient in eosinophils. Science. 2004;305:1773–1776. doi: 10.1126/science.1099472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humbles AA, Lloyd CM, McMillan SJ, Friend DS, Xanthou G, McKenna EE, et al. A critical role for eosinophils in allergic airways remodeling. Science. 2004;305:1776–1779. doi: 10.1126/science.1100283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Q, Monticelli LA, Saenz SA, Chi AW, Sonnenberg GF, Tang J, et al. T cell factor 1 is required for group 2 innate lymphoid cell generation. Immunity. 2013;38:694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, Doering TA, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1045–1054. doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang YJ, Kim HY, Albacker LA, Baumgarth N, McKenzie AN, Smith DE, et al. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:631–638. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 2012;36:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, Kephart GM, McKenzie AN, Kita H. IL-33-responsive lineage- CD25+ CD44(hi) lymphoid cells mediate innate type 2 immunity and allergic inflammation in the lungs. J Immunol. 2012;188:1503–1513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barlow JL, Bellosi A, Hardman CS, Drynan LF, Wong SH, Cruickshank JP, et al. Innate IL-13-producing nuocytes arise during allergic lung inflammation and contribute to airways hyperreactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:191–198. e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price AE, Liang HE, Sullivan BM, Reinhardt RL, Eisley CJ, Erle DJ, et al. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11489–11494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–1370. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mjosberg J, Spits H. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells-new members of the "type 2 franchise" that mediate allergic airway inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1093–1096. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mjosberg JM, Trifari S, Crellin NK, Peters CP, van Drunen CM, Piet B, et al. Human IL-25- and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1055–1062. doi: 10.1038/ni.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohrs M, Shinkai K, Mohrs K, Locksley RM. Analysis of type 2 immunity in vivo with a bicistronic IL-4 reporter. Immunity. 2001;15:303–311. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatch GE, Slade R, Harris LP, McDonnell WF, Devlin RB, Koren HS, et al. Ozone dose and effect in humans and rats. A comparison using oxygen-18 labeling and bronchoalveolar lavage. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:676–683. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slade R, Watkinson WP, Hatch GE. Mouse strain differences in ozone dosimetry and body temperature changes. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L73–L77. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.1.L73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain D, Keslacy S, Tliba O, Cao Y, Kierstein S, Amin K, et al. Essential role of IFNbeta and CD38 in TNFalpha-induced airway smooth muscle hyper-responsiveness. Immunobiology. 2008;213:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Lamm WJ, Albert RK, Chi EY, Henderson WR, Jr, Lewis DB. Influence of the route of allergen administration and genetic background on the murine allergic pulmonary response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:661–669. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McConnell R, Berhane K, Gilliland F, London SJ, Islam T, Gauderman WJ, et al. Asthma in exercising children exposed to ozone: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:386–391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scannell C, Chen L, Aris RM, Tager I, Christian D, Ferrando R, et al. Greater ozone-induced inflammatory responses in subjects with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:24–29. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.1.8680687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koren HS. Associations between criteria air pollutants and asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(Suppl 6):235–242. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atochina EN, Beers MF, Tomer Y, Scanlon ST, Russo SJ, Panettieri RA, Jr, et al. Attenuated allergic airway hyperresponsiveness in C57BL/6 mice is associated with enhanced surfactant protein (SP)-D production following allergic sensitization. Respir Res. 2003;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeda K, Haczku A, Lee JJ, Irvin CG, Gelfand EW. Strain dependence of airway hyperresponsiveness reflects differences in eosinophil localization in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L394–L402. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang LY, Levitt RC, Kleeberger SR. Differential susceptibility to ozone-induced airways hyperreactivity in inbred strains of mice. Exp Lung Res. 1995;21:503–518. doi: 10.3109/01902149509031755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishi Y, Shirato M, Nomura A, Sakamoto T, Uchida Y, Ohtsuka M, et al. Cloning of rat eotaxin: ozone inhalation increases mRNA and protein expression in lungs of brown Norway rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L171–L176. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.1.L171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnston RA, Mizgerd JP, Flynt L, Quinton LJ, Williams ES, Shore SA. Type I interleukin-1 receptor is required for pulmonary responses to subacute ozone exposure in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:477–484. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0315OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Q, Saenz SA, Zlotoff DA, Artis D, Bhandoola A. Cutting edge: Natural helper cells derive from lymphoid progenitors. J Immunol. 2011;187:5505–5509. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao YD, Zou JJ, Zheng JW, Shang M, Chen X, Geng S, et al. Promoting effects of IL-13 on Ca2+ release and store-operated Ca2+ entry in airway smooth muscle cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HY, Chang YJ, Subramanian S, Lee HH, Albacker LA, Matangkasombut P, et al. Innate lymphoid cells responding to IL-33 mediate airway hyperreactivity independently of adaptive immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:216–227. e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]