Abstract

Background

Takotsubo (or stress-induced) cardiomyopathy is characterized by transient left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Recent trends in patient volume, characteristics and outcomes in the United States are unknown.

Methods

Using 2007–2012 National Inpatient Sample data, we identified 22,005 adults (≥18 years) with a primary and 31,942 adults with a secondary discharge diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy (ICD-9 code 429.83) who underwent diagnostic coronary angiography.

Results

During 2007–2012, the incidence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy increased over 3-fold: 52/million discharges in 2007 to 178/million in 2012 (P < 0.001). We found a temporal increase in the prevalence of cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes, hypertension) and psychiatric disorders (P trend<0.0001 for all). In-hospital mortality was 1.1% and remained unchanged over this period (P=0.22). Compared to the primary diagnosis group, mortality in the secondary diagnosis group was higher (1.1% vs. 3.2%), and was associated with higher incidence of cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest and respiratory failure. Men represent 8% of patients in the primary diagnosis group and 12% in the secondary group. In both groups men had a higher incidence of shock, cardiac arrest and respiratory failure. While their mortality was higher than women in the primary group (3.0% vs. 0.9%; adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.85; 1.74 – 8.51), it was comparable in the secondary group (4.8% vs. 3.0%).

Conclusions

We found a marked increase in the hospitalization for takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the U.S. in recent years, suggesting higher incidence than prior reports. Although outcomes have remained favorable, there is an increasing burden of cardiovascular and psychiatric disorders in this population with growing cost of care. Risk of mortality is higher in men and in patients with underlying critical illness. The excess mortality in these groups appears to be mediated by greater severity of disease.

Keywords: stress, epidemiology, cardiomyopathy, echocardiography, shock

Introduction

Takotsubo (or stress-induced) cardiomyopathy is a non-ischemic cardiomyopathy characterized by left ventricular dysfunction, usually in the setting of acute psychological or physical stress that is likely mediated by catecholaminergic excess.1–4 The clinical presentation of takotsubo cardiomyopathy mimics acute coronary syndrome and is often accompanied by ST-segment elevation on the electrocardiogram and elevated cardiac biomarkers.5,6 The diagnosis is frequently made after exclusion of significant coronary disease by angiography and the demonstration of classic ballooning of the left ventricular apex.7

According to previous studies, takotsubo cardiomyopathy may represent 1–2% of all admissions for acute coronary syndromes.8,9 However, most of the prior studies were either single center studies or were limited to cross sectional analysis of 1–2 years of data, precluding assessment of the temporal variation in patient volume, characteristics and outcomes.10,11 Moreover data regarding recent epidemiology, clinical outcomes, cost of care and risk factors for mortality in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy are limited. Previous studies have found poor outcomes in men with takotsubo cardiomyopathy.12 Moreover, compared to those with a primary presentation of takotsubo cardiomyopathy, patients where the cardiomyopathy develops in the setting of another physical illness have a higher mortality.12 It remains unknown whether higher mortality in men and in those developing takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to critical illness is due to differences in clinical characteristics or comorbidities in these groups.13

To address this gap in knowledge, we used data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) – a large, nationally representative registry of hospitalized adults in the United States, to describe temporal trends in hospitalization and clinical outcomes in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. We also examined differences in clinical characteristics, complications and mortality in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy by gender.

Methods

Data sources

We used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), which is the largest, all-payer database of inpatient hospitalization in the United States.14 Details regarding the NIS database have been described previously.15 Briefly, the NIS comprises a random 20% sample of all inpatient hospitalizations in 46 U.S. states. The database includes de-identified information on patient demographics, admission status, discharge diagnoses, co-morbidities, procedures and outcomes for each sampled hospitalization. We used NIS data for years 2007–2012 to coincide with the time period when the diagnosis code for takotsubo cardiomyopathy was first introduced.

The database is constructed using 20% of all inpatient discharges from the reporting states for a given year, however, the sampling strategy evolved during our study period. Prior to 2012, the NIS database included 100% of discharges from a random 20% of all acute care hospitals in the U.S. (as defined by the American Hospital Association) stratified by hospital bedsize, ownership, rural/urban location and U.S. region. Patients admitted under observation status, as well as those admitted to short-term rehabilitation hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, and alcoholism or chemical dependency units were not included. Discharge weights are computed for the 20% sample to generate national estimates. Prior to release of the data, the AHRQ verifies discharge weights for the 20% sample against the total 100% sample and details of the validation process are available to the public.16 In 2012, a number of methodological changes were made to the sampling methodology. First, the discharge universe was redefined using the state inpatient database (SID) and long-term non-acute care hospitals were also excluded. Second, instead of including 100% of discharges from a random 20% of hospitals, the database included a random 20% of discharges from all (100%) acute care hospitals in the U.S. with the discharges stratified by hospital bed strength, ownership, rural/urban location and U.S. region. The updated methodology improved the stability of the estimates and reduced the margins of error by up to 50%. It also resulted in a reduction in overall national estimates by 4.3%.16 A revised set of discharge weights called ‘trend weights’ were generated for year 2012, as well as for all years preceding 2012 to ensure comparability across years and to facilitate trend analyses using data from previous years. 17,18 As recommended by the AHRQ, we used the updated trend weights in survey methods that accounted for clustering and stratification to generate national estimates by weighting the 20% sample for all years in this study.

Study Population & Variables

Each observation in the NIS represents an individual hospitalization with information regarding demographic characteristics (including age, sex, race and residential income quartile), discharge diagnoses and inpatient procedures performed during the index hospitalization. The discharge diagnoses are presented as one primary discharge diagnosis and up to 24 secondary discharge diagnoses. In addition up to 15 procedures are reported for each hospitalization. All diagnoses and procedures are available as International Classification of Diseases-9th Clinical Modification (ICD-9CM) codes. Within the NIS, ICD-9CM codes for several diagnoses and procedures are meaningfully combined into broad categories provided separately as Clinical Classification Software (CCS) diagnosis and procedure codes

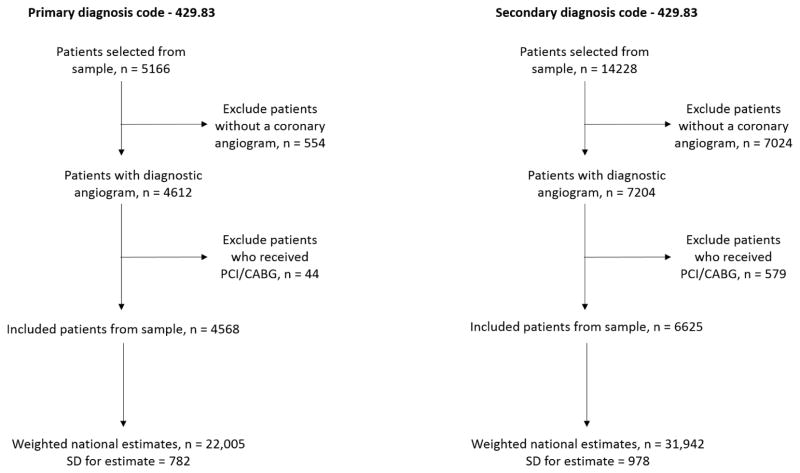

We identified all patients aged ≥ 18 years with a primary or a secondary discharge diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy using the ICD-9CM code 429.83, which has been used in prior studies to identify this disorder.10 While patients with a primary discharge diagnosis likely represent admissions where takotsubo cardiomyopathy was the primary reason for admission, those with a secondary diagnosis may include patients who 1) developed takotsubo cardiomyopathy secondary to another critical physical illness during the current admission, or 2) had a past history of takotsubo cardiomyopathy and were readmitted for either a related or an unrelated cause. Hence, we limited our study to patients who were likely to have received the recommended diagnostic work up during the index hospitalization. Since most accepted diagnostic criteria for takotsubo cardiomyopathy (revised Mayo Clinic criteria, Gothenburg criteria, etc.) require exclusion of significant coronary artery disease,8,19,20 we excluded all patients who did not undergo a diagnostic coronary angiogram (CCS code 47) during this index hospitalization or underwent diagnostic angiography that was followed by percutaneous or surgical coronary revascularization (CCS codes 45 and 44 respectively). The patient selection process for the study is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowsheet for the patient selection process in the present study

Among the selected cases we preferentially used CCS codes to identify co-morbidities and major procedures. Where CCS codes were unavailable, ICD-9CM codes were used. The hospitalizations were further classified by insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, private, other), admission type (elective or non-elective), length of stay and cost of hospitalization. Cost of hospitalizations was computed by multiplying charges for each hospitalization with the cost-to-charge ratios for each hospital for a given year, and inflation adjusted to the year 2012.21 The cost-to-charge ratios were not available for 2012, and cost analysis was limited to 2007–2011. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. The data for age, sex, diagnoses and procedures was available for 100% of patients, income quartile was missing for 206 (1.8%) patients, primary payer for 11 (0.1%), with data for disposition and admission type (elective vs. non-elective) missing for <10 patients (<0.1%), which is not reported in pursuance of the NIS data agreement.

Statistical analysis

In the conduct of our analysis, we followed the recommendations of AHRQ and used methods appropriate for analysis of survey data. To ensure the accuracy of our national estimates and variances, we used the survey analysis methods that accounted for clustering and stratification of patients for all categorical and continuous variables in our descriptive analyses.22 Trend analyses were performed using the Cochran-Armitage test of trend for categorical variables, and survey-specific linear regression for continuous variables.

First, to select patients who presented for a primary presentation consistent with takotsubo cardiomyopathy, we examined the total number of discharges with a primary discharge diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy for each-calendar year and obtained weighted estimates for each year. We also calculated the number of discharges per-million adult discharges for each year. We then examined temporal trends in takotsubo hospitalizations for both absolute volume and as a proportion of hospitalized adults. Next, we examined calendar-year trends in patient characteristics, secondary discharge diagnoses, co-morbidities, inpatient procedures, patient disposition, cost and length of stay and insurance status. Variables that were not normally distributed (e.g. cost and length of stay), were log-transformed and trends in geometric means were examined.23 We also examined differences in patient characteristics and outcomes by gender.

Next we used a multivariable logistic regression model for survey data to examine the effect of individual patient characteristics on our primary outcome in patients with a primary discharge diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. We included patient gender, age, race, secondary diagnoses (heart failure, valvular heart disease and arrhythmia), comorbid conditions (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, fluid electrolyte disorder, liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, coagulopathy and psychiatric disorder), inpatient procedures (diagnostic cardiac catheterization) and calendar-year as covariates in our model. We also accounted for hospital level clustering and stratification of patients using the CLUSTER and STRATA statements respectively.

We then repeated this analysis in selected patients where takotsubo cardiomyopathy was listed as a secondary discharge diagnosis, and compared differences in patient characteristics and outcomes between these two patient groups. To assess the independent effect of primary or secondary diagnosis on mortality, we performed multivariate analysis including all patient-level characteristics from the above model and included primary and secondary status as additional covariates.

We used SAS 9.4 software (SAS institute, Cary, NC) for all analyses. The study was reviewed by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board, which waived the requirement for informed consent. The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health under award K08HL122527 (Dr. Girotra). The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents.

Results

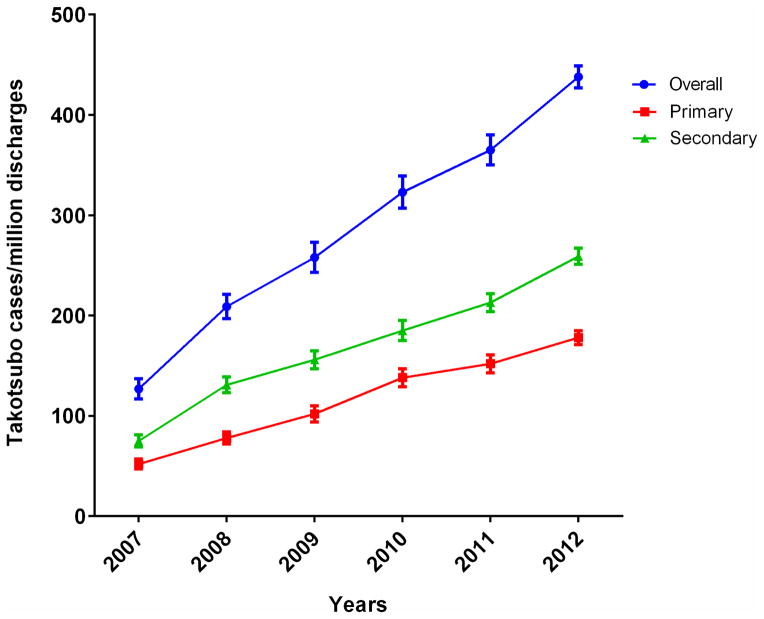

During 2007–2012, we found 4,568 patients corresponding to a national estimate of 22,005 patients who were discharged with a primary diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States (Figure 1). The number of hospitalizations increased nearly three-fold, from 1642 cases in 2007 to 5480 cases in 2012, whereas the number of hospitalizations per-million adult discharges increased over 3-fold - from 52 cases per million adult discharges in 2007 to 178 per million in 2012 (Figure 2). Additionally, there were an estimated 31,942 patients with a secondary diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy during this period who satisfied our inclusion criteria (Figure 1), and the overall number of hospitalizations with takotsubo cardiomyopathy as a primary or a secondary diagnosis increased from 75 cases per million adult discharges in 2007 to 259 per million in 2012 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Calendar-year trends in hospitalization for takotsubo cardiomyopathy (number per 1 million discharges) in the United States – primary discharge diagnosis, secondary discharge diagnosis and overall.

Table 1 shows temporal trends in patient characteristics for patients with primary diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy during the study period. In this group, the mean age was 65.7 years, and the proportion of patients over the age of 65 years increased slightly from 51.8% in 2007 to 55.8% in 2012 (P = 0.0008). More than 9 out of 10 patients were women (92.0%) and the gender distribution remained unchanged over time. A majority of patients were white (71.1%), with a smaller proportion of black (4.8%) and other minority (9.3%) patients, with improved reporting of race over time. A substantial number of patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy had hypertension (64.2%), diabetes (20.5%), dyslipidemia (47.7%), and their prevalence increased over time (P<0.0001 for all). Notably, 29.7% of patients had an underlying mental health disorder, with increasing prevalence between 2007 and 2012 (P<0.0001). Cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest complicated the clinical course of 4.0% and increased from 3.2% in 2007 to 4.1% in 2012 (P for trend <0.0001), while 1.2% of patients had cardiac arrest without much change over time. During hospitalization, 4.8% of patients received mechanical ventilation and 2.8% of patients received intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP). While the use of IABP declined from 3.9% in 2007 to 2.4% in 2012 (P for trend = 0.04), the use of mechanical ventilation remained unchanged (P for trend = 0.06). Temporal trends for patient characteristics in patients with a secondary diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy were similar to those with in the primary diagnosis group and are reported in supplemental table 1.

Table 1.

Trends in characteristics for patients hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

| Characteristics | Hospital admissions for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy | P value (trend) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Overall | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | ||

| Estimated patient numbers (weighted numbers ± SD) | 22005 (782) | 1642 (173) | 2516 (208) | 3242 (258) | 4327 (294) | 4798 (304) | 5480 (214) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Mean Age (SEM) | 65.7 (0.2) | 64.5 (0.7) | 66.0 (0.5) | 65.2 (0.5) | 65.6 (0.4) | 66.2 (0.4) | 65.9 (0.4) | 0.31 |

| Age ≥ 65 year (%) | 55.5 (0.8) | 51.8 (2.9) | 57.0 (2.2) | 52.3 (1.9) | 54.4 (1.8) | 58.6 (1.6) | 55.8 (1.6) | 0.0008 |

| Female Sex | 92.0 (0.4) | 92.8 (1.7) | 90.8 (1.6) | 92.9 (1.0) | 93.1 (0.8) | 91.3 (0.8) | 91.6 (0.9) | 0.19 |

|

| ||||||||

| Race | 0.10 | |||||||

| White | 71.7 (1.3) | 58.9 (4.6) | 67.4 (3.2) | 67.8 (3.8) | 72.0 (3.2) | 74.3 (2.1) | 77.3 (1.6) | |

| Black | 4.5 (0.4) | 3.3 (1.0) | 4.1 (1.0) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.2 (0.8) | 5.7 (1.0) | 4.3 (0.6) | |

| Others | 9.1 (0.6) | 9.0 (1.8) | 6.9 (1.3) | 8.2 (1.3) | 8.5 (1.4) | 9.6 (1.2) | 10.8 (1.2) | |

| Missing/Unknown | 14.7 (1.3) | 28.8 (4.8) | 21.6 (3.4) | 19.8 (4.1) | 15.3 (3.3) | 10.4 (2.0) | 7.7 (1.1) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Income quartiles§ | <0.0001 | |||||||

| 0–25 | 22.2 (0.9) | 20.5 (2.6) | 19.2 (2.3) | 22.7 (2.4) | 23.3 (1.9) | 19.2 (1.7) | 25.5 (1.6) | |

| 26 to 50 | 24.6 (0.8) | 20.6 (2.8) | 27.2 (2.1) | 21.5 (1.9) | 24.5 (1.9) | 25.2 (1.7) | 26.0 (1.4) | |

| 51 to 75 | 26.8 (0.8) | 28.8 (2.7) | 25.4 (2.2) | 27.8 (2.2) | 26.6 (1.8) | 29.7 (1.8) | 23.9 (1.4) | |

| 76 to 100 | 26.4 (1.1) | 30.1 (3.4) | 28.2 (2.9) | 28.0 (2.8) | 25.6 (2.3) | 25.9 (2.3) | 24.6 (1.5) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Secondary diagnoses | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Cardiogenic shock | 4.0 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.7) | 4.2 (1.1) | 3.2 (0.6) | 5.3 (0.8) | 4.1 (0.6) | 0.0001 |

| HF | 23.7 (0.7) | 23.0 (2.3) | 27.2 (1.9) | 20.6 (1.8) | 22.9 (1.5) | 24.9 (1.5) | 23.8 (1.3) | 0.82 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1.2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.8 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0.04 |

| Valvular heart disease | 13.9 (0.6) | 14.7 (2.0) | 15.3 (1.5) | 13.1 (1.5) | 12.3 (1.2) | 15.2 (1.3) | 13.5 (1.0) | 0.42 |

| Arrhythmia | 21.1 (0.6) | 16.9 (2.1) | 19.4 (1.8) | 20.0 (1.6) | 21.2 (1.4) | 21.6 (1.2) | 23.3 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Acute cerebrovascular disease | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.78 |

|

| ||||||||

| Comorbid medical conditions | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Hypertension | 64.2 (0.7) | 60.9 (2.6) | 64.2 (2.0) | 59.2 (1.8) | 62.4 (1.7) | 66.7 (1.6) | 67.6 (1.4) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 18.0 (0.6) | 15.6 (2.0) | 16.6 (1.6) | 16.9 (1.6) | 19.3 (1.4) | 17.5 (1.3) | 19.2 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 2.6 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.6) | 2.0 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 47.7 (0.9) | 48.4 (2.9) | 42.2 (2.7) | 42.9 (2.2) | 48.6 (1.8) | 47.5 (1.8) | 52.5 (1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5.2 (0.3) | 3.9 (1.1) | 4.2 (0.9) | 5.5 (0.9) | 4.9 (0.7) | 6.1 (0.8) | 5.4 (0.7) | 0.002 |

| Sepsis | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.003 |

| Liver disease | 4.4 (0.3) | 3.4 (1.0) | 2.8 (0.7) | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.4 (0.7) | 6.3 (0.8) | 5.1 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 15.7 (0.6) | 11.4 (1.8) | 16.4 (1.7) | 16.0 (1.6) | 15.1 (1.1) | 17.8 (1.3) | 15.1 (1.1) | 0.02 |

| Cancer | 12.2 (0.5) | 10.4 (1.6) | 9.7 (1.3) | 13.0 (1.3) | 9.4 (1.0) | 14.2 (1.1) | 13.8 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Fluid/electrolyte disorder | 19.3 (0.6) | 16.7 (2.0) | 20.4 (1.8) | 17.0 (1.6) | 19.4 (1.4) | 21.1 (1.4) | 19.5 (1.2) | 0.005 |

| Coagulation disorder | 2.6 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.4) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||||

| Comorbid mental health conditions | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Any psychiatric diagnosis | 29.7 (0.7) | 28.2 (3.0) | 23.6 (1.8) | 27.1 (1.8) | 31.3 (1.6) | 30.4 (1.4) | 32.7 (1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Mood disorder | 17.8 (0.6) | 16.7 (2.3) | 13.8 (1.5) | 18.2 (1.7) | 19.5 (1.4) | 16.9 (1.1) | 19.2 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety disorder | 14.4 (0.5) | 12.4 (1.9) | 10.1 (1.3) | 11.0 (1.3) | 13.0 (1.1) | 14.8 (1.2) | 19.8 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Procedures | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 4.8 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.9) | 5.6 (1.0) | 4.6 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.6) | 6.6 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.7) | 0.06 |

| IABP | 2.8 (0.3) | 3.9 (1.1) | 2.0 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.5) | 2.4 (0.5) | 0.04 |

|

| ||||||||

| Administrative/financial details | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Payment source | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Medicare | 55.5 (0.8) | 54.0 (2.9) | 54.8 (2.1) | 54.2 (2.0) | 54.3 (2.0) | 55.8 (1.6) | 57.8 (1.6) | |

| Medicaid | 5.3 (0.4) | 4.9 (1.5) | 5.1 (1.0) | 5.4 (0.9) | 4.7 (0.8) | 5.0 (0.7) | 6.2 (0.8) | |

| Private insurance | 32.9 (0.8) | 33.9 (2.6) | 33.6 (2.2) | 34.5 (2.0) | 35.3 (1.9) | 33.4 (1.5) | 28.9 (1.4) | |

| Others | 6.3 (0.4) | 7.2 (1.5) | 6.5 (1.2) | 5.9 (1.0) | 5.7 (0.8) | 5.8 (0.7) | 7.1 (0.8) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Admission type (%elective) | 6.5 (0.5) | 7.5 (1.6) | 6.3 (1.5) | 5.1 (1.1) | 7.1 (1.2) | 7.0 (1.2) | 6.1 (0.8) | 0.80 |

|

| ||||||||

| Disposition | 0.32 | |||||||

| Home or self-care | 82.0 (0.7) | 82.8 (2.3) | 79.9 (2.1) | 80.8 (1.5) | 84.4 (1.3) | 81.6 (1.3) | 82.2 (1.2) | |

| Short term hospital | 1.2 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.4) | |

| Skilled care facility | 7.0 (0.4) | 7.1 (1.6) | 7.4 (1.2) | 7.2 (0.9) | 6.4 (0.9) | 7.1 (0.8) | 7.0 (0.7) | |

| Home health care | 8.4 (0.4) | 7.5 (1.6) | 9.9 (1.5) | 8.8 (1.0) | 7.3 (0.9) | 9.1 (0.9) | 8.0 (0.9) | |

| Unknown/AMA | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | |

| Died | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Hospitalization cost (US$) | 12417θ (260) | 12296 (571) | 12341 (525) | 11765 (423) | 12526 (610) | 12849 (491) | - θ | 0.58 |

|

| ||||||||

| Length of stay (days – mean ± SEM) | 3.6 (0.1) | 3.6 (0.2) | 3.9 (0.2) | 3.5 (0.1) | 3.4 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.1) | 3.4 (0.1) | 0.08 |

|

| ||||||||

| In-hospital mortality | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.22 |

Values represent percentages (standard errors), unless otherwise specified

Abbreviations: SD – standard deviation, SEM - standard error of mean, HF – heart failure, COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IABP – intra-aortic balloon pump, AMA – against medical advice

Trends for white race vs others

Trends for lowest income quartile vs. others

2012 cost data not available

There were several differences between patients with a primary versus a secondary diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy (Table 2). Compared to patients with a primary diagnosis, those with a secondary diagnosis were older (mean age for primary 65.7 years vs. 66.6 years for secondary, P 0.0008), less likely to be women (92.0% vs. 88.1%), and have a psychiatric diagnosis (29.7% vs. 26.6%, P = 0.0007), but were more likely to have HF (23.7% vs. 37.5%, P<0.0001), acute cerebrovascular disease (1.0% vs. 2.8%), cardiac dysrhythmia (21.1% vs. 28.8%), chronic kidney disease (5.2% vs. 7.3%) or sepsis (1.0% vs. 5.0%, P<0.0001 for all). They were also more likely to experience cardiogenic shock (4.0% vs. 6.7%), cardiac arrest (1.2% vs. 3.9%) and respiratory failure requiring mechanical respiratory support (4.8% vs. 16.6%, P<0.0001).

Table 2.

Differences in characteristics of takotsubo cardiomyopathy patients as “primary” vs. secondary” discharge diagnosis

| Characteristics | Overall | Primary | Secondary | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admissions (weighted numbers ± SD) | 53947 (1616) | 22005 (783) | 31942 (978) | |

|

| ||||

| Patient characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mean Age (SEM) | 66.8 (0.1) | 65.7 (0.2) | 66.6 (0.2) | 0.0008 |

| Age ≥ 65 year | 57.7 (0.5) | 55.5 (0.8) | 59.2 (0.6) | 0.0002 |

| Female sex | 89.7 (0.3) | 92.0 (0.4) | 88.1 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Race | 0.20 | |||

| White | 71.9 (1.1) | 71.7 (1.3) | 72.0 (1.2) | |

| Black | 5.0 (0.3) | 4.5 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.4) | |

| Others | 9.2 (0.4) | 9.1 (0.6) | 9.2 (0.5) | |

| Missing/Unknown | 14.0 (1.1) | 14.7 (1.3) | 13.5 (1.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Income quartiles§ | 0.51 | |||

| 0–25 | 22.2 (0.9) | 22.2 (0.9) | 24.8 (0.9) | |

| 26 to 50 | 24.6 (0.8) | 24.6 (0.8) | 26.3 (0.8) | |

| 51 to 75 | 26.8 (0.8) | 26.8 (0.8) | 25.7 (0.8) | |

| 76 to 100 | 26.4 (1.1) | 26.4 (1.1) | 23.2 (1.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Cardiovascular diagnoses | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cardiogenic shock | 5.6 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.3) | 6.7 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| HF | 31.9 (0.5) | 23.7 (0.7) | 37.5 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 2.8 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 3.9 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

| Valvular heart disease | 13.5 (0.4) | 13.9 (0.6) | 13.3 (0.5) | 0.42 |

| Arrhythmia | 25.7 (0.4) | 21.1 (0.6) | 28.8 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Acute cerebrovascular disease | 2.1 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.2) | 2.8 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Comorbid medical conditions | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hypertension | 63.1 (0.5) | 64.2 (0.7) | 62.3 (0.6) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes | 22.6 (0.4) | 20.5 (0.6) | 24.1 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 46.0 (0.6) | 47.7 (0.9) | 44.8 (0.7) | 0.0046 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6.4 (0.2) | 5.2 (0.3) | 7.3 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| Acute kidney injury | 8.8 (0.3) | 4.6 (0.3) | 11.7 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

| Sepsis | 5.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 7.7 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 5.3 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.3) | 5.9 (0.3) | 0.0013 |

| COPD | 18.8 (0.4) | 15.7 (0.6) | 20.9 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer | 13.2 (0.3) | 12.2 (0.5) | 13.9 (0.4) | 0.01 |

| Fluid/electrolyte disorder | 26.5 (0.5) | 19.3 (0.6) | 31.5 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Coagulation disorder | 4.2 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.2) | 5.2 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Comorbid mental health disorders | ||||

|

| ||||

| Any psychiatric diagnosis | 27.9 (0.5) | 29.7 (0.7) | 26.6 (0.6) | 0.0007 |

| Mood disorder | 17.0 (0.4) | 17.8 (0.6) | 16.4 (0.5) | 0.06 |

| Anxiety disorder | 13.2 (0.3) | 14.4 (0.5) | 12.4 (0.4) | 0.002 |

|

| ||||

| Procedures | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 11.8 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.3) | 16.6 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

| IABP | 3.3 (0.2) | 2.8 (0.3) | 3.7 (0.2) | 0.008 |

|

| ||||

| Administrative/financial details | ||||

|

| ||||

| Payment source | <0.0001 | |||

| Medicare | 58.0 (0.5) | 55.5 (0.8) | 59.7 (0.7) | |

| Medicaid | 5.8 (0.3) | 5.3 (0.4) | 6.2 (0.3) | |

| Private insurance | 29.2 (0.5) | 32.9 (0.8) | 26.6 (0.6) | |

| Others | 7.0 (0.3) | 6.3 (0.4) | 7.4 (0.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Admission type (% elective) | 8.0 (0.5) | 6.5 (0.5) | 9.0 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Disposition | <0.0001 | |||

| Home or self-care | 72.0 (0.5) | 82.1 (0.7) | 65.1 (0.6) | |

| Short term hospital | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.2) | |

| Skilled care facility | 12.2 (0.3) | 7.0 (0.4) | 15.7 (0.5) | |

| Home health care | 11.4 (0.3) | 8.4 (0.5) | 13.5 (0.4) | |

| Unknown/AMA | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | |

| Death | 2.3 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.2) | 3.2 (0.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Length of stay (days – mean ± SEM) | 3.5 (0.1) | 3.6 (0.1) | 6.2 (0.1) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Cost of stay (US$) θ | 16,723 (308) | 12417 (260) | 19668 (422) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| In-hospital mortality | 2.3 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.2) | 3.2 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

Values represent percentages (standard errors), unless otherwise specified

Abbreviations: SD – standard deviation, SEM - standard error of mean, HF – heart failure, COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IABP – intra-aortic balloon pump, AMA – against medical advice

Trends for white race vs others

Trends for lowest income quartile vs. others

2012 cost data not available

We found several differences in patient characteristics by gender (Table 3). Compared to women, men with a primary diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy were younger (66.1 years vs. 61.0 years, P <0.0001), more likely to be black (4.1% vs. 9.4%, P = 0.0001), and have chronic kidney disease (5.0% vs. 7.7%, P = 0.03) but were less likely to have a mental health disorder (30.6% vs. 19.8%). Notably, compared to women, the hospital course for men was more likely to be complicated by cardiogenic shock (3.8% vs. 6.0%, P = 0.03), cardiac arrest (1.0% vs. 3.3%, P 0.0001) and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation (4.4% vs. 10.1%, P < 0.0001). Similar gender differences were observed in patients with a secondary diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy and men were younger and had a higher incidence of cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest and respiratory failure was higher (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in characteristics of takotsubo cardiomyopathy patients by gender

| Primary diagnosis | Secondary diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Characteristics | Females | Males | P value | Females | Males | P value |

| Admissions (weighted numbers ± SD) | 20248 (715) | 1757 (122) | 28150 (870) | 3793 (177) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Mean Age (SEM) | 66.1 (0.2) | 61.0 (0.9) | <0.0001 | 67.4 (0.2) | 60.9 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Age ≥ 65 year (%) | 56.2 (0.8) | 46.7 (2.6) | 0.0002 | 61.1 (0.7) | 44.9 (1.7) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Race | 0.0002 | 0.26 | ||||

| White | 72.2 (1.3) | 65.5 (2.8) | 72.4 (1.2) | 69.3 (1.9) | ||

| Black | 4.1 (0.4) | 9.1 (1.5) | 5.2 (0.4) | 5.9 (0.9) | ||

| Others | 9.0 (0.6) | 10.3 (1.7) | 9.0 (0.5) | 10.7 (1.2) | ||

| Missing/Unknown | 14.7 (1.3) | 15.1 (2.3) | 13.4 (1.2) | 14.1 (1.6) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Income quartiles§ | 0.51 | 0.45 | ||||

| 0–25 | 22.0 (0.9) | 24.1 (2.5) | 25.0 (0.9) | 23.8 (1.6) | ||

| 26 to 50 | 24.5 (0.8) | 25.3 (2.4) | 26.2 (0.8) | 26.5 (1.8) | ||

| 51 to 75 | 26.8 (0.8) | 27.4 (2.3) | 25.4 (0.8) | 17.9 (1.7) | ||

| 76 to 100 | 26.7 (1.1) | 23.2 (2.5) | 23.4 (1.0 | 21.9 (1.8) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Secondary diagnoses | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Cardiogenic shock | 3.8 (0.3) | 6.0 (1.2) | 0.03 | 6.4 (0.3) | 8.9 (1.0) | 0.008 |

| HF | 24.3 (0.7) | 17.1 (2.1) | 0.003 | 38.2 (0.7) | 32.5 (1.7) | 0.002 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1.0 (0.2) | 3.3 (0.9) | 0.0001 | 3.6 (0.2) | 6.5 (0.9) | <0.0001 |

| Valvular heart disease | 14.1 (0.6) | 10.8 (1.6) | 0.07 | 13.9 (0.5) | 9.0 (1.1) | 0.0004 |

| Arrhythmia | 20.9 (0.6) | 23.9 (2.2) | 0.18 | 28.2 (0.6) | 33.6 (1.8) | 0.002 |

| Acute cerebrovascular disorder | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.5) | 0.96 | 2.7 (0.2) | 3.2 (0.6) | 0.49 |

|

| ||||||

| Comorbid medical conditions | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Hypertension | 64.7 (0.8) | 59.2 (2.4) | 0.03 | 63.6 (0.7) | 52.8 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 20.6 (0.6) | 18.7 (1.9) | 0.37 | 24.7 (0.6) | 19.2 (1.4) | 0.0005 |

| Dyslipidemia | 47.9 (0.9) | 45.6 (3.2) | 0.46 | 45.8 (0.7) | 37.3 (1.7) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5.0 (0.3) | 7.7 (1.4) | 0.03 | 7.3 (0.4) | 7.0 (0.9) | 0.76 |

| Acute kidney injury | 4.5 (0.3) | 6.2 (1.3) | 0.13 | 10.9 (0.5) | 17.5 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Fluid/electrolyte disorder | 19.3 (0.6) | 19.6 (2.0) | 0.87 | 31.1 (0.7) | 34.4 (1.6) | 0.05 |

| Sepsis | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.7) | 0.09 | 7.0 (0.4) | 12.7 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer | 11.9 (0.5) | 15.2 (2.0) | 0.07 | 13.5 (0.5) | 17.0 (1.4) | 0.009 |

| Coagulation disorder | 2.4 (0.2) | 4.7 (1.1) | 0.006 | 4.8 (0.3) | 8.5 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Comorbid mental health disorders | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Any psychiatric diagnosis | 30.6 (0.8) | 19.8 (2.0) | <0.0001 | 27.6 (0.6) | 19.7 (1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Mood disorder | 18.4 (0.7) | 11.2 (1.6) | 0.0004 | 17.1 (0.5) | 11.3 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety disorder | 14.9 (0.6) | 9.1 (1.5) | 0.003 | 12.8 (0.4) | 9.1 (1.0 ) | 0.003 |

|

| ||||||

| Procedures | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 4.4 (0.3) | 10.1 (1.6) | <0.0001 | 15.6 (0.5) | 24.2 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

| IABP | 2.7 (0.3) | 4.0 (1.0) | 0.14 | 3.5 (0.3) | 5.3 (0.8) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Admission type (% elective) | 6.6 (0.5) | 5.7 (1.4) | 0.55 | 9.0 (0.6) | 9.0 (1.1) | 0.96 |

|

| ||||||

| Disposition | <0.0001 | 0.01 | ||||

| Home or self-care | 81.9 (0.7) | 84.0 (2.0) | 65.2 (0.7) | 64.3 (1.7) | ||

| Short term hospital | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.6) | ||

| Skilled care facility | 6.9 (0.4) | 8.2 (1.5) | 15.7 (0.5) | 15.8 (1.3) | ||

| Home health care | 8.9 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.9) | 13.7 (0.5) | 11.5 (1.1) | ||

| Unknown/AMA | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.3) | ||

| Death | 0.9 (0.2) | 3.0 (0.9) | 3.0 (0.2) | 4.8 (0.8) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hospitalization cost (US$) θ | 12277 (249) | 13994 (863) | 0.07 | 18914 (404) | 25662 (1480) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||

| Length of stay (days – mean ± SEM) | 3.5 (0.1) | 3.8 (0.2) | 0.90 | 6.1 (0.1) | 7.4 (0.3) | 0.0002 |

|

| ||||||

| In-hospital mortality (unadjusted) | 0.9 (0.2) | 3.0 (0.9) | 0.0003 | 3.0 (0.2) | 4.8 (0.8) | 0.008 |

|

| ||||||

| Adjusted OR for mortality (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 3.85 (1.74, 8.51) | 0.0009 | 1 (reference) | 1.1 (0.81, 3.74) | 0.55 |

Values represent percentages (standard errors), unless otherwise specified

Abbreviations: SD – standard deviation, SEM - standard error of mean, HF – heart failure, COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IABP – intra-aortic balloon pump, AMA – against medical advice

OR - Odds ratio (OR) after adjustment for patient characteristics

2012 cost data not available

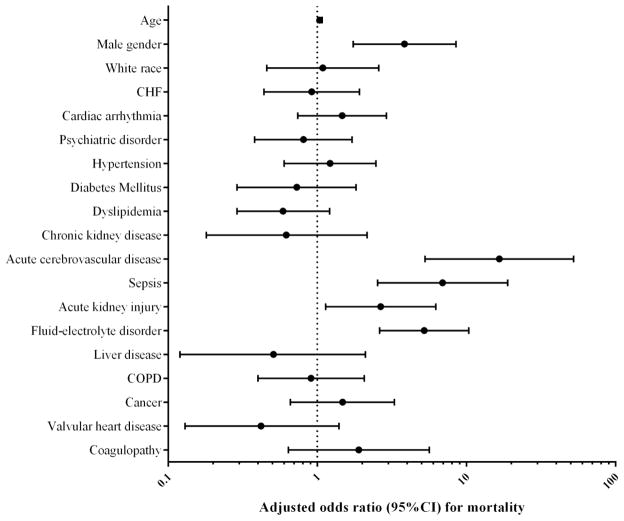

In the patients with primary diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy, in-hospital mortality was 1.1% and remained unchanged during the study period, even after adjustment for trends in patient characteristics over time (P for trend = 0.82, Supplemental Figure 1). Compared to those with a primary diagnosis, the in hospital mortality in patients with secondary discharge diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy was nearly three-fold higher, 1.1% vs. 3.2% (unadjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.01, 95% C.I. 2.18 – 4.15, P<0.0001), even after adjusting for baseline patient characteristics (adjusted OR for mortality 1.60, 95% C.I. 1.13 – 2.27, P = 0.008) (Supplemental table 2). Compared to women with a primary diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy, risk of in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in men (0.9% vs. 3.0%, P = 0.0005). Higher mortality in men was noted even after adjustment of baseline differences in patient characteristics (adjusted OR 3.85; 95% CI 1.74 – 8.51, P = 0.0009, Figure 3). On the other hand in the secondary diagnosis group, compared to women, the unadjusted mortality in men was higher (3.0% vs. 4.8%, P=0.008), but was not observed after adjustment for differences in baseline characteristics (risk-adjusted OR 1.1, 95% C.I. 0.81 – 3.74).

Figure 3.

Multivariate logistic regression for mortality with adjustment for patient characteristics (c-statistic − 0.88)

The average length of stay in our study was 3.6 days, and remained unchanged over time (P = 0.08). Moreover, length of stay was similar between men and women (3.6 days vs. 4.0 days, P = 0.86). Compared to the primary diagnosis group, the average length of stay in the secondary diagnosis group was longer (3.6 days vs. 6.2 days, P <0.0001) but did not change over time. A majority of the patients (79.8%) were discharged home, and the pattern of discharge disposition did not change over time (P for trend = 0.32). The overall average cost of hospitalization was US$ 16,723 and cost for patients with a primary diagnosis was lower (US$ 12,417) compared to those with a secondary diagnosis (US$ 19,668) of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Notably, the cost of stay remained unchanged during the study period (P=0.58) for either group.

Discussion

In this study using nationally representative data, we found an over 3-fold increase in hospitalization due to takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States over a 6-year period. Prevalence of chronic comorbidities and complications such as cardiogenic shock in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy has increased over time. Overall mortality in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy is low and has remained unchanged in recent years. Although takotsubo cardiomyopathy is more common in women, mortality is nearly four-fold higher in men compared to women even after accounting for differences in baseline characteristics. Higher mortality in men with takotsubo cardiomyopathy is present despite their younger age, and is likely due to a higher prevalence of cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The reported number of patients with a secondary discharge diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy who had undergone an angiographic coronary evaluation was 1.5 times more than the primary group, and had a similar 3-fold increase over during 2007–2012. These patients are likely to include those developing takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the setting of another critical illness and have a much higher mortality than those with a primary presentation; however, the excess mortality is explained by the difference in patient characteristics between these groups. A number of our findings merit further discussion.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States. We found that hospitalization for takotsubo cardiomyopathy increased from 52 cases per million adult discharges to 178 cases per million between 2007 and 2012. We could not determine whether the increase in hospitalization rates was due to a higher index of suspicion for this diagnosis among clinicians or a true increase in the incidence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. It is possible that an increasing trend in hospitalization for takotsubo cardiomyopathy is due to greater recognition of the disease given more widespread availability of diagnostic imaging.5,24 A similar trend was noted in an observational study from Sweden (SWEDEHEART registry) during 2005–2013,25 which likely represent increasing recognition of this entity. In the year 2012, where 5480 cases were reported as a primary diagnosis, takotsubo cardiomyopathy represented 0.7% of the annual volume of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in the United States (735,000).26 The additional 7960 patients with a secondary diagnosis of takotsubo in 2012 and underwent a diagnostic coronary angiogram likely represents takotsubo cardiomyopathy precipitated in the setting of another critical illness. A nearly equal number of patients who did not undergo a coronary angiogram during the study as they may represent related or unrelated re-hospitalizations in patients with a prior history of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Given, the trajectory of patient admissions for takotsubo cardiomyopathy observed in our study, it is likely that the true incidence of this entity may exceed the current estimates of 1–2% of AMI, especially if the secondary presentation is accounted for appropriately.

The patient characteristics in our study, including gender distribution, age at presentation and the prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities, are similar to those reported previously.12,27 Among patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy we found increasing prevalence of cardiogenic shock, and chronic cardiovascular comorbidities like diabetes and hypertension over time. It is reassuring to note that the increase in burden of co-morbidities and illness severity did not lead to worse outcomes over time, as overall mortality was low at 1.1%, and remained unchanged during the study period. Some studies have suggested a possible protective role for diabetes in the development of takotsubo cardiomyopathy, inferred from lower prevalence of diabetes in this group.28 While we found lower incidence of some of cardiovascular risk factors, particularly diabetes in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy (20%) compared to AMI (30%) reported in published literature,29 we did not find an association between diabetes and mortality in takotsubo patients. Further studies are need to investigate the association between cardiovascular risk factors, like diabetes and hypertension, and incidence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. We also find an increasing incidence of psychiatric disorders in these patients, which we speculate to be due to a few reasons. First, it is likely that the important triggers are now better known and psychiatric diagnosis is pursued. Second, patients with a history of psychiatric disorder presenting with physical complaints are now pursued with further testing and a diagnosis for takotsubo cardiomyopathy is established, while previously the disorder may have been mischaracterized.

Low mortality with takotsubo cardiomyopathy in our study is consistent with a number of previous studies examining patients with a primary presentation of takotsubo cardiomopathy,27,30–32 Our reported mortality is lower than the 4.2% mortality reported in another study,33 which pooled the patients with a primary and secondary diagnosis together. Using this approach, we found a similarly high mortality during 2007–2012, driven by the excess mortality in the secondary group. Our findings add to the results of a meta-analysis of 37 studies (2,120 patients), which showed that mortality in patients with a primary presentation of takotsubo cardiomyopathy was low (1%) but was up to 10-fold higher in patients where stress-induced cardiomyopathy developed due to an underlying critical illness.12

Consistent with prior studies, we found that more than 90% of patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy were women.12 However, it was noteworthy that the risk of mortality was nearly fourfold in men compared to women, despite their younger age and similar comorbidity profile. We found that higher mortality in men persisted after risk-adjustment for baseline characteristics and may be associated higher prevalence of complications, including cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, respiratory failure and need for hemodynamic support with an IABP. The slightly higher proportion of men in the secondary diagnosis group without any excess mortality raises the question about delayed presentation of men with a primary presentation may drive the excess complications and higher mortality compared to women. The mechanism behind gender-based differences in prevalence and outcomes of takotsubo cardiomyopathy remain poorly studied. Some studies have suggested that estrogen plays an important role in modulating both the myocardial adrenergic receptor distribution and the catecholaminergic response to stress, which may explain the higher incidence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy in women.13,34,35 However, these findings need further confirmation.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, we identified our cases using ICD-9 discharge codes, and details of the presentation for the patients are unavailable limiting our ability to independently confirm the diagnosis. Although this limitation is difficult to overcome in an administrative database, we limited our analysis to patients who underwent a diagnostic coronary catheterization during the index hospitalization and where acute coronary syndrome as the underlying etiology was likely excluded. While it is possible that some of the cases of takotsubo cardiomyopathy who were diagnosed using non-invasive approaches may have been excluded with this approach, patients who did not undergo coronary angiogram during the index stay do not satisfy the widely accepted criteria necessary for the diagnosis,19 and are hence not included in the analysis. Second, the NIS data does not provide information on important clinical predictors of outcomes including disease severity, left ventricular ejection fraction and baseline functional status of patients, which can potentially confound the adjustment for patient characteristics. Third, given the administrative nature of the database, it is not possible to reliably differentiate comorbidities from complications of hospitalization. Fourth, we could not further characterize patients who underwent non-invasive testing, like echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and could not assess their utilization in the management of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Fifth, data regarding specific medical management such as inotropes and antithrombotic agents are not available in the NIS. Lastly, the NIS does not provide information that can be used to reliably predict pre-hospital events that may have served as likely precipitants or long term outcomes after discharge, both of which would require dedicated studies in the future.

In conclusion, we found more than three-fold increase in hospitalization for takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States over a 6 year period, 2007 through 2012, which likely represents an increasing recognition of this disease. In spite of increasing medical comorbidities and complications, overall mortality has remained low, which may allude to the self-limiting nature of this disease. However, given the increase in patient volume, the healthcare impact of this previously rare entity is likely to expand. We note that the mortality in men is nearly four-times higher compared to women, and is associated with a higher prevalence of cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest and respiratory failure. While mortality in patients where takotsubo cardiomyopathy may have developed in the setting of another primary physical illness is higher, no gender differences were observed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Girotra is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health under award K08HL122527.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Akashi YJ, Goldstein DS, Barbaro G, Ueyama T. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new form of acute, reversible heart failure. Circulation. 2008;118(25):2754–2762. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.767012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352(6):539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. European heart journal. 2006;27(13):1523–1529. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel SM, Chokka RG, Prasad K, Prasad A. Distinctive clinical characteristics according to age and gender in apical ballooning syndrome (takotsubo/stress cardiomyopathy): an analysis focusing on men and young women. Journal of cardiac failure. 2013;19(5):306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metzl MD, Altman EJ, Spevack DM, Doddamani S, Travin MI, Ostfeld RJ. A case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy mimicking an acute coronary syndrome. Nature clinical practice. Cardiovascular medicine. 2006;3(1):53–56. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0414. quiz 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Annals of internal medicine. 2004;141(11):858–865. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelliccia F, Greco C, Vitale C, Rosano G, Gaudio C, Kaski JC. Takotsubo syndrome (stress cardiomyopathy): an intriguing clinical condition in search of its identity. The American journal of medicine. 2014;127(8):699–704. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008;155(3):408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eitel I, Behrendt F, Schindler K, et al. Differential diagnosis of suspected apical ballooning syndrome using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. European heart journal. 2008;29(21):2651–2659. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshmukh A, Kumar G, Pant S, Rihal C, Murugiah K, Mehta JL. Prevalence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States. American heart journal. 2012;164(1):66–71 e61. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parodi G, Del Pace S, Carrabba N, et al. Incidence, clinical findings, and outcome of women with left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome. The American journal of cardiology. 2007;99(2):182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh K, Carson K, Shah R, et al. Meta-analysis of clinical correlates of acute mortality in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The American journal of cardiology. 2014;113(8):1420–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.01.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider B, Athanasiadis A, Sechtem U. Gender-related differences in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Heart failure clinics. 2013;9(2):137–146. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HCUP Databases. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Jul, 2014. [Accessed October 24, 2014]. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khera R, Cram P, Lu X, et al. Trends in the Use of Percutaneous Ventricular Assist Devices: Analysis of National Inpatient Sample Data, 2007 Through 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houchens RLRD, Elixhauser A, Jiang J. [accessed 07/20/2014];Nationwide Inpatient Sample redesign: Final report. 2014 Apr 4; available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/reports/NISRedesignFinalReport040914.pdf.

- 17.HCUP. [Accessed 07/20/2014, 2014];Trend Weights for HCUP NIS Data. 2014 Available at http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/trendwghts.jsp.

- 18.HCUP. [Accessed October 24, 2014];HCUP national estimates. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/nationalestimates/508_course/508course.htm-{D7E23702-C5FE-42FF-A185-EDF87F3D7FD8.

- 19.Madias JE. Why the current diagnostic criteria of Takotsubo syndrome are outmoded: A proposal for new criteria. International journal of cardiology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redfors B, Shao Y, Lyon AR, Omerovic E. Diagnostic criteria for takotsubo syndrome: a call for consensus. International journal of cardiology. 2014;176(1):274–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed 5/30/2014];Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation calculator. 2014 http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

- 22.Houchens REA. HCUP Method Series Report # 2003–02. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [Accessed 5/13/2014]. 2005. Final Report on Calculating Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Variances, 2001. ONLINE June 2005 (revised June 6, 2005) Available: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/CalculatingNISVariances200106092005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bland JM, Altman DG. Transformations, means, and confidence intervals. Bmj. 1996;312(7038):1079. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7038.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerra F, Rrapaj E, Pongetti G, et al. Differences and similarities of repolarization patterns during hospitalization for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and acute coronary syndrome. The American journal of cardiology. 2013;112(11):1720–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redfors B, Vedad R, Angeras O, et al. Mortality in takotsubo syndrome is similar to mortality in myocardial infarction - A report from the SWEDEHEART registry. International journal of cardiology. 2015;185:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eitel I, von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Bernhardt P, et al. Clinical characteristics and cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(3):277–286. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madias JE. Low prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with Takotsubo syndrome: A plausible ‘protective’ effect with pathophysiologic connotations. European heart journal. Acute cardiovascular care. 2015 doi: 10.1177/2048872615570761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, Sorel M, Selby JV, Go AS. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;362(23):2155–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elesber AA, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Wright RS, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Four-year recurrence rate and prognosis of the apical ballooning syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50(5):448–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parodi G, Bellandi B, Del Pace S, et al. Natural history of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Chest. 2011;139(4):887–892. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Zenovich AG, et al. Acute and reversible cardiomyopathy provoked by stress in women from the United States. Circulation. 2005;111(4):472–479. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153801.51470.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brinjikji W, El-Sayed AM, Salka S. In-hospital mortality among patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a study of the National Inpatient Sample 2008 to 2009. American heart journal. 2012;164(2):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyon AR, Rees PS, Prasad S, Poole-Wilson PA, Harding SE. Stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy--a novel pathophysiological hypothesis to explain catecholamine-induced acute myocardial stunning. Nature clinical practice Cardiovascular medicine. 2008;5(1):22–29. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueyama T, Ishikura F, Matsuda A, et al. Chronic estrogen supplementation following ovariectomy improves the emotional stress-induced cardiovascular responses by indirect action on the nervous system and by direct action on the heart. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2007;71(4):565–573. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.