Abstract

The optical confinement generated by metal-based nanoapertures fabricated on a silica substrate has recently enabled single-molecule fluorescence measurements to be performed at physiologically relevant background concentrations of fluorophore-labeled biomolecules. Nonspecific adsorption of fluorophore-labeled biomolecules to the metallic cladding and silica bottoms of nanoapertures, however, remains a critical limitation. To overcome this limitation, we have developed a selective functionalization chemistry whereby the metallic cladding of gold nanoaperture arrays is passivated with methoxy-terminated, thiol-derivatized polyethylene glycol (PEG), and the silica bottoms of those arrays are functionalized with a binary mixture of methoxy- and biotin-terminated, silane-derivatized PEG. This functionalization scheme enables biotinylated target biomolecules to be selectively tethered to the silica nanoaperture bottoms via biotin-streptavidin interactions, and reduces the non-specific adsorption of fluorophore-labeled ligand biomolecules. This, in turn, enables the observation of ligand biomolecules binding to their target biomolecules even under greater than 1 µM background concentrations of ligand biomolecules, thereby rendering previously impracticable biological systems accessible to single-molecule fluorescence investigations.

Keywords: Zero-mode waveguide, nanoaperture, single-molecule fluorescence, microscopy, fluorescence resonance energy transfer, self-assembled monolayer, translation factor

Nature often exploits weak intermolecular interactions to permit the reversible assembly of macromolecular complexes, achieve high binding specificities, and facilitate functionally important biomolecular dynamics.1 Although, in principle, single-molecule fluorescence (smF) microscopies provide powerful tools for dissecting the mechanisms of the fundamentally important biological processes that involve weakly interacting target and ligand biomolecules,2 in practice, these investigations remain challenging. This is because the observation of these weak intermolecular interactions on a timescale that is experimentally accessible to conventional smF microscopies requires prohibitively high background concentrations of ligand biomolecules in solution – a condition that results in high background noise and, consequently, compromises the quality of smF data.3

Many strategies have been devised to reduce the noise arising from high background concentrations of ligand biomolecules in smF microscopy experiments. Notably, strategies that specifically activate fluorophores of interest (e.g., fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET),4 photoactivatable fluorophores,5,6 and photogenic fluorophores7) or confine the excitation field (e.g., total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy,8 and confocal microscopy9) have been used to selectively excite only those ligand biomolecules that are bound to a target biomolecule. Perhaps the most effective strategy described to date is the use of metal-based, sub-wavelength nanoapertures, often called zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs), to generate a confined excitation field near the silica bottom of a nanoaperture structure, thereby selectively exciting only those ligand biomolecules that are bound to a target biomolecule that is localized within the confined excitation volume.3 While nanoaperture fluorescence microscopy is currently the only optical confinement-based microscopy that permits smF measurements to be made at physiologically-relevant, µM background concentrations of ligand biomolecules (Fig. 1), the non-specific adsorption of these ligand biomolecules to the metallic and silica nanoaperture surfaces often compromises the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) of the smF data. In order to overcome this problem, an orthogonal surface chemistry process was developed to selectively passivate the metallic cladding and silica bottoms of nanoapertures. Unfortunately, this process is quite limited, as it uses negatively charged poly(vinyl) phosphonic acid (PVPA) to minimize the non-specific adsorption of negatively charged, fluorophore-labeled deoxynucleotides for single-molecule DNA sequencing applications,10 and it is not generally applicable to other biomolecular systems. The lack of significant progress in the development of more generalizable surface passivation chemistries has thus far restricted the use of nanoaperture fluorescence microscopy to only a handful of biological systems11–13 over the decade since nanoaperture fluorescence microscopy of biological systems was first introduced.3

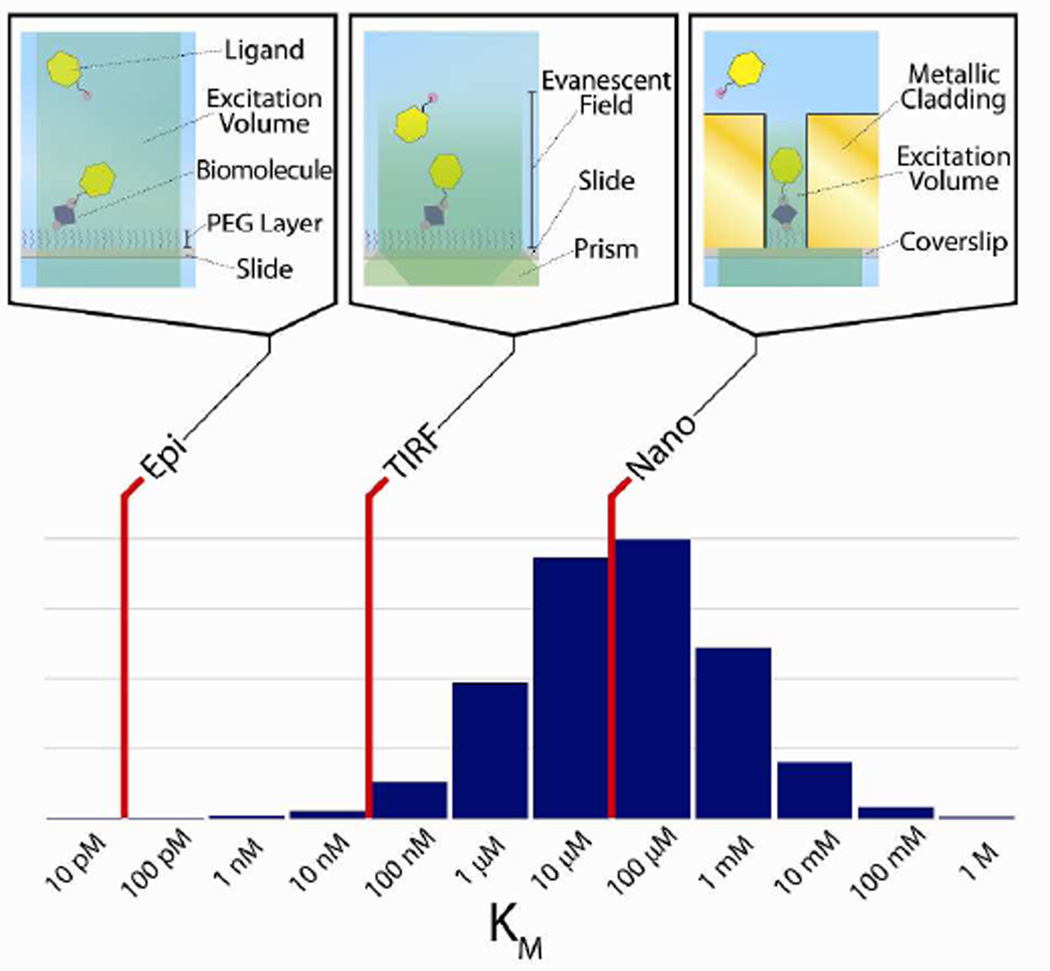

Figure 1.

Diagram of concentration ranges accessible by various microscopy techniques. Red lines represent the upper limit of the background concentration of ligand biomolecules that can be employed in smF experiments using epi-fluorescence microscopy (Epi), TIRF microscopy (TIRF), and nanoaperture fluorescence microscopy (Nano). The microscope schematics connected to each red line provide molecular-level diagrams corresponding to each technique (upper panel). The histogram shows the distribution of Michaelis constants (KM), a characterization of the interactions between enzymes and their corresponding substrates, of all eukaryotic enzymes in the BRENDA enzyme database.14 This distribution is analogous to the distribution of background concentrations of ligand biomolecules required to observe interactions with a target biomolecule on an experimentally accessible timescale using smF microscopies (lower panel).

Here, we report a cost-effective and widely accessible method for the fabrication and selective functionalization of microfluidic devices containing gold nanoaperture arrays for smF microscopy investigations. A key advantage of our approach is the robust passivation of the nanoaperture surfaces against the non-specific adsorption of biomolecules. For the gold cladding, this is provided by the formation of self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on the gold surface using methoxy-terminated, thiol-derivatized PEG. SAMs have traditionally been employed to mitigate non-specific adsorption, and expansively ordered, thiolate SAMs readily form on gold surfaces.15,16 Notably, SAMs with terminal PEG blocks have been shown to provide particularly non-specific adsorption-resistant, biocompatible backgrounds,16–18 as PEG chains are extensively hydrated, and the non-specific adsorption of biomolecules induces enthalpically unfavorable desolvation and entropic penalties from compression of a monolayer.19 By combining this approach for passivating the gold cladding with a fully orthogonal approach for functionalizing the silica bottom of the nanoapertures using a binary mixture of methoxy- and biotin-terminated, silane-derivatized PEG, we have developed a scheme that enables specific tethering of biotinylated target biomolecules to the silica bottom of the nanoapertures while robustly blocking the non-specific adsorption of ligand biomolecules to both the gold cladding and the silica bottom of the nanoapertures. As a proof-of-principle, we demonstrate that the time-resolved fluorescence signals from an individual biotinylated, surface-tethered, FRET donor- and acceptor-fluorophore labeled protein, bacterial peptide chain release factor 1 (RF1) – a protein that has never been shown to be compatible with PVPA-passivated aluminum-based nanoapertures – can be easily monitored in the presence of more than 1 µM background concentrations of FRET acceptor-labeled RF120 without detectable deterioration of the SBR from excitation cross-talk.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

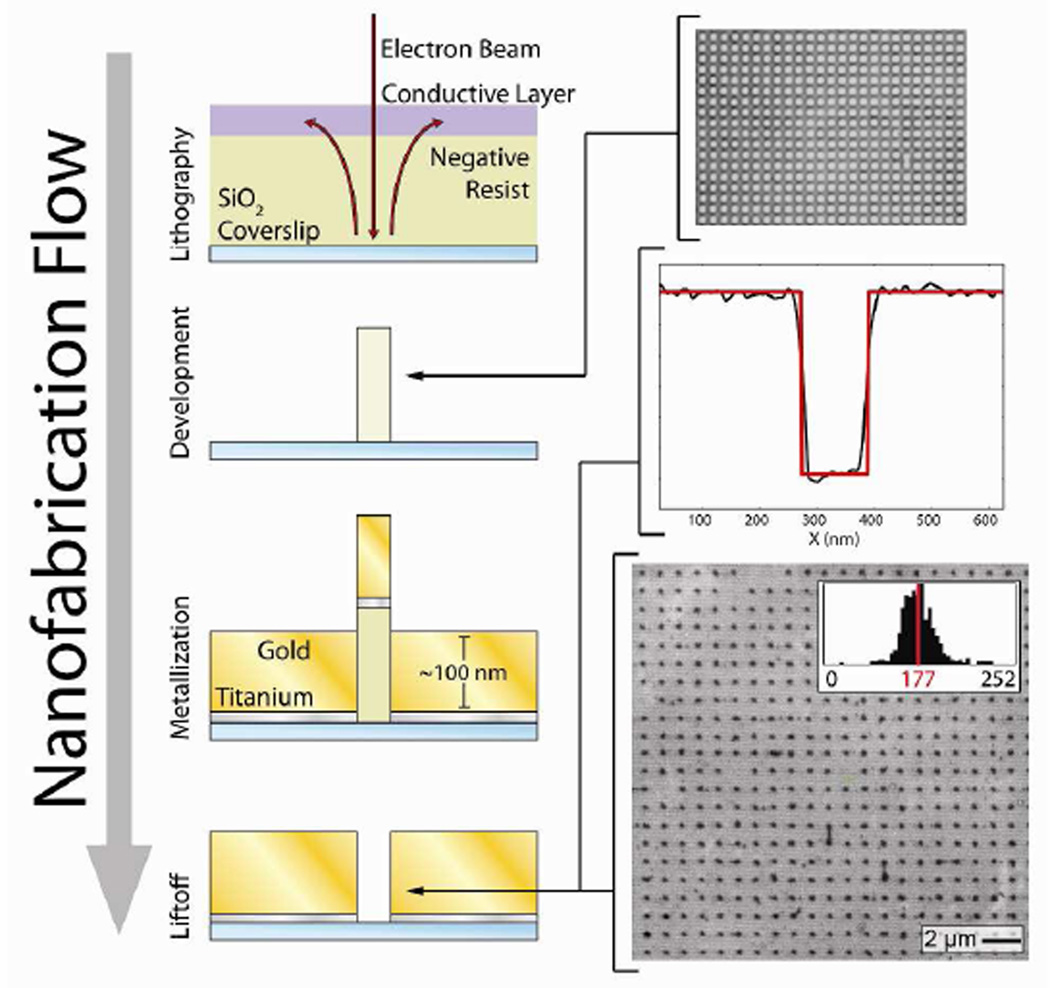

Gold nanoaperture arrays were fabricated on borosilicate coverslips using an electron-beam lithography process in which nanoapertures are formed in the relief of metal-embedded pillars of cross-linked polymer (Fig. 2). During the development of the electron-beam lithography steps of this process, we found that the poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) poly(styrenesulfonate) conductive layer employed (applied to the Ma-N 2403 negative-tone resist in order to prevent charging during electron beam writing) failed to be completely removed by water washing following electron-beam writing. It is possible that this layer, which has a pH of 1.5–2.5 at room temperature, crosslinks to the Ma-N 2403 negative-tone resist layer, which is composed of a phenolic resin with a bisazide photoactive compound. Therefore, instead of washing with water, treatment with acetic acid, which would be expected to reverse the crosslinking equilibrium, was used to produce well-defined pillars. Typically, this process yields ~80% of the intended nanoapertures, with poor pillar adhesion prior to metallization or incomplete lift-off being the most common causes of defects. Despite these issues, this process yields nanoapertures with an average diameter of 177 nm, with a relatively narrow diameter distribution (Fig. 2), and a spacing of 1 – 5 µm. Within these dimensions, gold nanoapertures exhibit both the strong electromagnetic confinement responsible for the reduction in excitation volume as well as the gold surface plasmon-mediated fluorescence enhancement that is characteristic of smaller diameter gold nanoapertures.21,22

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram of the nanoaperture fabrication process. Negative-tone electron-beam lithography crosslinks patterns in the negative resist on a silica coverslip; excess electrons are removed to a ground via a conductive layer. Pillars of patterned, cross-linked resist remain following substrate exposure to aqueous developer. The top panel shows a wide-field, optical microscope image of a pre-metallization pillar array. An optically transparent, adhesion layer of titanium is then deposited with electron-beam evaporation. Subsequently, a layer of gold is deposited with electron-beam evaporation, such that the cross-linked resist remains solvent exposed. Nanoapertures are formed in the relief of the pillars following solvent-based liftoff. The middle panel shows an atomic force microscope image cross-section of a typical nanoaperture; the red line is a boxcar function fit with a 115 nm step length. The bottom panel shows a scanning electron microscope image of a nanoaperture array, post-fabrication; the average diameter of the nanoapertures in this array is 177 ± 16 nm (1σ, n = 499).

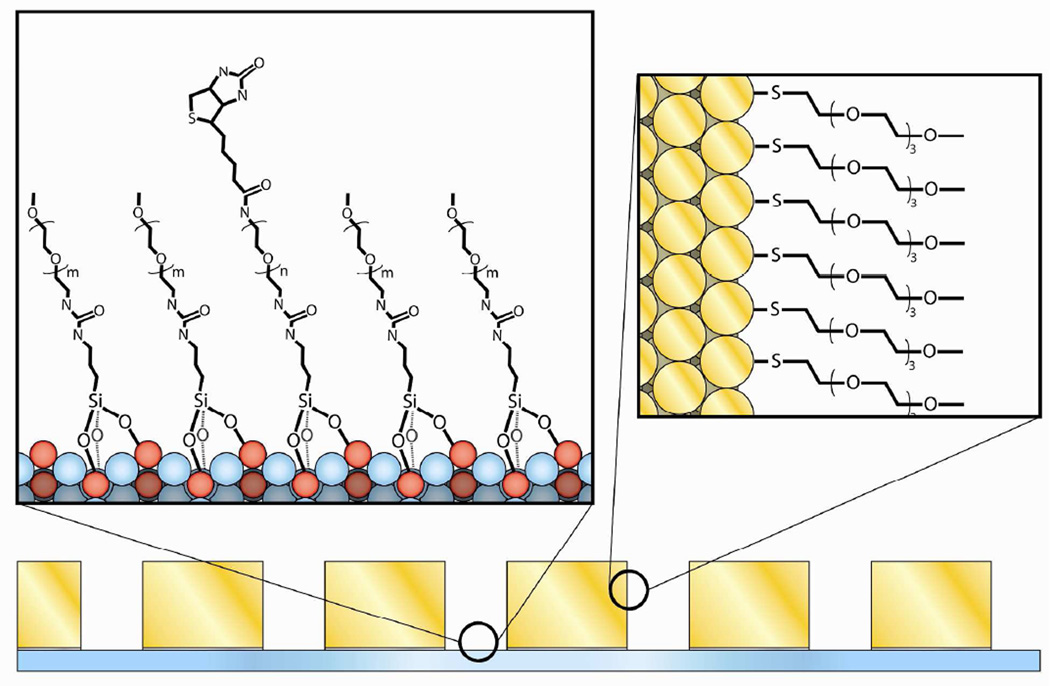

Following nanofabrication, the gold nanoaperture arrays were passivated with a SAM formed using methoxy-terminated, thiol-derivatized PEG (mPEG-SH) and a SAM formed using a binary mixture of methoxy-terminated, triethoxy-functionalized, silane-derivatized PEG (mPEG-Si) and biotin-terminated, triethoxy-functionalized, silane-derivatized PEG (biotin-PEG-Si) to create biomolecule adsorption-resistant backgrounds on the gold cladding and the silica nanoaperture bottoms, respectively (Fig. 3). As silanes have a propensity to covalently bond to gold,23 thiolation of the gold cladding was performed prior to silanization of the silica nanoaperture bottoms to yield more homogeneously passivated nanoapertures. Following extensive substrate cleaning, the passivation process begins with a 12 hour incubation in a solution prepared by dissolving mPEG-SH in anhydrous ethanol to a final PEG concentration of 1 mM – thereby ensuring sufficient time for SAM formation.16 The substrates were then silanized for 24 hours in a solution of 100 µM biotin-PEG-Si and mPEG-Si in anhydrous toluene at the specified molar ratio of biotin-PEG-Si to mPEG-Si.

Figure 3.

Molecular-level schematic diagram of thiol and silane passivated surfaces. The gold surfaces of the nanoaperture arrays were passivated with a SAM formed using mPEG-SH, and the borosilicate surfaces of the nanoaperture arrays were passivated with a SAM formed using a binary mixture of biotin-PEG-Si and mPEG-Si.

Microfluidic devices were then assembled by mounting substrates comprising fully passivated, gold nanoaperture arrays onto quartz microscope slides that had been drilled to form sets of inlet/outlet ports, cleaned and passivated with mPEG-Si using a previously published procedure,24 and divided into multiple, separate reaction flow cells using adhesive spacers (Fig. S1).25 Once the substrates had been mounted onto the adhesive spacers, epoxy was used to seal the sides of the flow cells. This multiple flow cell geometry allows for several independent experiments and controls to be performed in the same microfluidic device, thereby eliminating device fabrication and processing as a source of experimental variation.

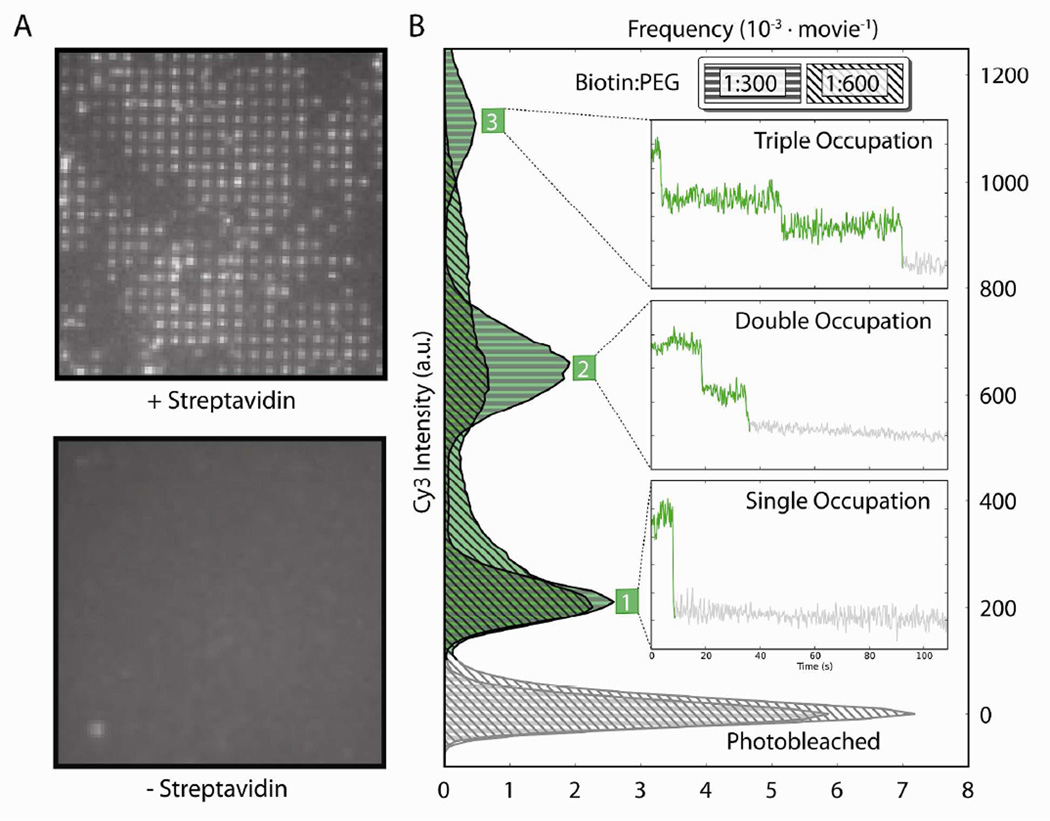

To assess the robustness of our gold nanoaperture passivation scheme, we performed several nanoaperture fluorescence microscopy experiments using a biotinylated, Cy3 FRET donor- and Cy5 FRET acceptor-labeled, double-cysteine mutant of the Escherichia coli RF1 (bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5). The ability to specifically localize a biotinylated target biomolecule from solution to the silica bottom of a nanoaperture is dependent upon the formation of a biotin-streptavidin-biotin bridge between the biotin-PEG-Si on the silica bottom of the nanoaperture, streptavidin, and the biotinylated target biomolecule – in this case, bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5. After incubation of a flow cell with 1 µM streptavidin for 5 minutes at room temperature, washing with Tris-polymix buffer, incubation with 1 pM bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 for 5 minutes at room temperature, and washing with Imaging buffer, wide-field fluorescence imaging of the flow cell yielded fluorescence emission from bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 in a well-defined pattern corresponding to the nanoaperture array (Fig. 4A, top panel). When performing the same experiment in a neighboring flow cell, but in the absence of streptavidin, no fluorescence emission was detected from the nanoaperture array. Even imaging of regions of bulk silica just proximal to the nanoaperture array revealed only minimal fluorescence emission from spatially localized bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5, which we attributed to the non-specific adsorption of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 to defects in the borosilicate surface of the coverslip substrate (Fig. 4A, bottom panel). Thus, the passivating SAMs resisted the non-specific adsorption of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 to both the gold cladding and the silica bottoms of the gold nanoaperture arrays, while the presence of streptavidin at the bottom of the nanoaperture arrays allowed the specific localization of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 to the nanoaperture arrays. In addition to demonstrating the robustness of our SAM-based passivation scheme, these results show that the presence of neither the gold cladding nor the mPEG-SH SAMs interfered with passivation of the silica regions of the substrates with the biotin-PEG-Si and mPEG-Si SAMs.

Figure 4.

(A) Streptavidin-dependence of nanoaperture occupation. After incubating bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 in a flow cell with streptavidin, Cy3 fluorescence was observed in a pattern corresponding to that of the nanoaperture arrays, demonstrating that bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 was specifically localized to the silica bottoms of the nanoapertures (upper panel); the nanofabrication defects described in the text result in the lack of fluorescence in some of the regions where nanoapertures should be located. After incubating bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 in a second flowcell without streptavidin, Cy3 fluorescence was not observed from the nanoaperture array under the same imaging conditions; moreover, only minimal Cy3 fluorescence emission was observed from regions of bulk silica just proximal to the nanoaperture array (lower panel). (B) Tunable nanoaperture occupation. Histograms show the distributions of Cy3 fluorescence intensities observed over 100 seconds from nanoapertures in flow cells that had been passivated with a 1:300 or a 1:600 ratio of biotin-PEG-Si:mPEG-Si and then incubated with both bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 and streptavidin. Insets show discrete photobleaching events in Cy3 fluorescence intensity versus time trajectories that contribute to the histogram peaks and correspond to the occupancy of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 in individual nanoapertures.

We expect that the biotin-PEG-Si that is responsible for localizing streptavidin, and therefore bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5, to the silica nanoaperture bottoms via a biotin-streptavidin-biotin bridge should be Poisson-distributed throughout the nanoapertures; thus, whereas individual nanoapertures may contain zero, one, two, three, or more surface-tethered bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules, the exact distribution that is observed is dependent upon the ratio of biotin-PEG-Si to mPEG-Si employed during passivation – the larger the ratio, the greater the probability of observing multiple surface-tethered bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules per nanoaperture. To demonstrate this tunable control over nanoaperture occupation, we characterized the Cy3 fluorescence emission from single nanoapertures containing surface-tethered bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 in flow cells that have been passivated using our passivation scheme with particular ratios of biotin-PEG-Si to mPEG-Si. Normalized histograms were constructed of the intensity of Cy3 fluorescence emitted from individual nanoapertures in flow cells passivated with 1:600 (n = 173, where n is the number of nanoapertures that were characterized) and 1:300 (n = 195) biotin-PEG-Si:mPEG-Si that were both incubated with 1 µM streptavidin for 5 minutes at room temperature, washed with Tris-polymix buffer, incubated with 100 nM bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 for 5 minutes at room temperature, and washed with Imaging buffer to remove all unbound bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 (Fig. 4B). As expected, the distributions of the average Cy3 fluorescence intensity per nanoaperture are resolved into discrete peaks that correspond to discrete numbers of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules per nanoaperture. By correlating the number of individual Cy3 photobleaching events observed in the Cy3 fluorescence intensity versus time trajectories to the Cy3 fluoresence intensity observed per nanoaperture, we determined the absolute number of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules that corresponded to each peak in the histogram; the peaks in the histogram of Cy3 intensities correspond to nanoapertures that contain either one, two, or three biotin-streptavidin-biotin-tethered, fluorescing bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules (Fig. 4B, insets). As expected, doubling the biotin-PEG-Si: mPEG-Si ratio from 1:600 to 1:300 increases the populations of Cy3 fluorescence intensities corresponding to higher numbers of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules per nanoaperture. In addition, control over the distribution of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules per nanoaperture can be achieved by altering the concentrations and incubation times of streptavidin and bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5. For the nanoaperture arrays of the dimensions used here, we find that a 1:1000 ratio of biotin-PEG-Si: mPEG-Si with a 5 minute incubation at room temperature in 1 µM streptavidin followed by a 5 minute incubation at room temperature in 10–100 pM bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 yields a maximal population of nanoapertures that contain a single bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecule. Taken together with the streptavidin dependence shown in Figure 4A, our ability to predictably control the distribution of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules per nanoaperture by altering the ratio of biotin-PEG-Si: mPEG-Si demonstrates that the tethering of bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules to the silica nanoaperture bottoms is specifically dependent on the presence of a biotin-streptavidin-biotin bridge. Moreover, the chemistries employed are general enough to produce similar results in different nanoaperture geometries (e.g., squares) and with other metallic claddings that can form thiol SAMs (e.g., silver).

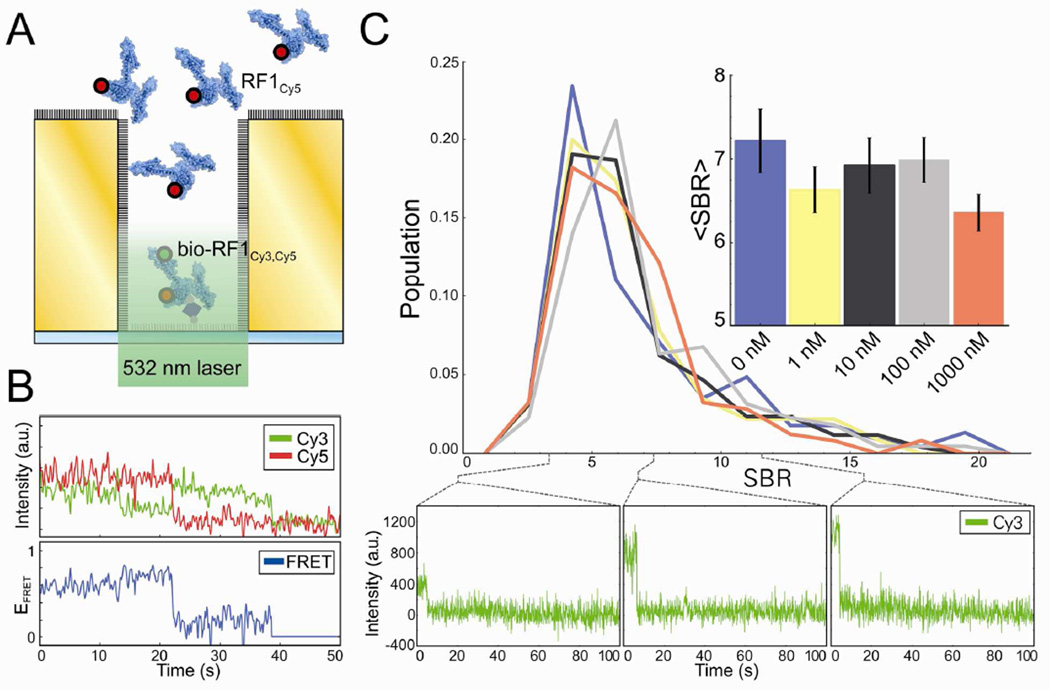

High background concentrations of ligand biomolecules and/or the non-specific adsorption of ligand biomolecules cause deterioration of the SBR in FRET-based smF experiments used to characterize weak biomolecular interactions – a limitation of FRET-based smF experiments that we expect our passivated, gold-based nanoapertures to overcome. In order to simulate the conditions of such an experiment without the usual complications to the FRET efficiency versus time trajectories that are introduced by the binding and dissociation of FRET acceptor-labeled ligand biomolecules from solution to individual, surface-tethered, FRET donor-labeled target biomolecules, we performed the FRET-based titration experiment diagrammed in Figure 5A. Briefly, we used a biotin-streptavidin-biotin bridge to specifically tether bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 to the silica nanoaperture bottoms of a fully passivated (1:1000 biotin-PEG-Si:mPEGSi) nanoaperture array and imaged a single flow cell at successively higher background solution concentrations of a Cy5 FRET acceptor-labeled variant of RF1 (RF1Cy5). To observe FRET signals arising from individual bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules tethered to the silica nanoapertures bottoms, the Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence intensities from individual, single bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 occupancy nanoapertures (ICy3 and ICy5, respectively) were converted into FRET efficiency, EFRET = ICy5/(ICy3+ICy5), which is a ratiometric measure of acceptor-fluorophore fluorescence. Although we were able to observe FRET signals arising from nanoapertures containing single bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules, the resulting EFRET versus time trajectories were characterized by a very low SBR (Fig. 5B). It is possible that this reduction in the SBR of EFRET versus time trajectories is caused by quenching of Cy3 and/or Cy5 that arises from close proximity of these fluorophores to the gold surface, by a red-shift of the fluorescence emission of Cy5 past our filter bandwidth, or that our bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 construct exists mostly in a conformation where Cy3 and Cy5 are too far away from each other so as to undergo appreciable energy transfer – an unlikely explanation, as we have observed energy transfer between Cy3 and Cy5 in TIRF-based FRET experiments using this same bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 construct (Pulukkunat, D.K.; Gonzalez Jr., R.L. unpublished results).

Figure 5.

(A) Schematic diagram of a nanoaperture fluorescence microscopy experiment designed to simulate the effect of increasing background concentrations of a FRET acceptor-labeled ligand biomolecule on a FRET-based nanoaperture fluorescence microscopy experiment. (B) A typical FRET signal from a single bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 in a nanoaperture. Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence intensities versus time trajectories are plotted on top, and the corresponding EFRET versus time trajectory is plotted below. (C) Distributions of Cy3 SBRs (calculated as the change in Cy3 fluorescence intensity due to photobleaching divided by the standard deviation of pure background fluorescence) imaged with 0 nM (n=136), 1 nM (n=137), 10 nM (n=155), 100 nM (n=131), and 1000 nM (n=146) background concentrations of RF1Cy5. Representative Cy3 fluorescence intensity versus time trajectories at specific SBRs from the 1000 nM RF1Cy5 data set are shown below. The inset shows the average SBRs with bootstrapped, 1σ error bars (n=1000).

In order to quantify the ability of our nanoapertures to resist the SBR deterioration caused by high ligand biomolecule concentrations in solution and/or non-specific adsorption of ligand biomolecules to the nanoaperture surfaces, we calculated the SBR distributions of Cy3 fluorescence intensity observed during this experiment. As a reference, the SBR of the analogous TIRF microscopy experiment drops prohibitively low with greater than ~50 nM of RF1Cy5 in solution. After nonlinear least squares fitting a step function to each Cy3 fluorescence intensity versus time trajectory observed in single bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 occupancy nanoapertures, we calculated the SBR as the Cy3 fluorescence intensity difference due to photobleaching divided by the standard deviation of pure background fluorescence (measured using the last 50 photobleached timepoints of each Cy3 fluorescence intensity versus time trajectory), and plotted the SBR distribution of ~130–150 single bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules per background concentration of RF1Cy5 that was tested (Fig. 5C). We observed an insignificant decrease in the average SBR at the highest background concentration of RF1Cy5 we tested (1 µM), and presumably the fully passivated, gold nanoaperture arrays reported here would continue to enable detection of single bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 molecules with adequate SBR at concentrations of RF1Cy5 much greater than 1 µM. Notably, this robust passivation would also be particularly effective in fluorescence colocalization-type smF experiments in which fluorophore-labeled ligand biomolecules in solution are directly excited by a laser excitation source and are observed to interact with either unlabeled or differentially fluorophore labeled target biomolecules tethered to the bottoms of the nanoapertures.

CONCLUSION

The significant SBR deterioration caused by the non-specific adsorption of ligand biomolecules onto the metallic and silica surfaces of nanoaperture arrays, as well as difficulties in the nanofabrication, passivation, and microscopy of nanoaperture arrays, have been major limiting factors for the widespread adoption of nanoaperture fluorescence microscopy for smF studies of biological systems. By combining a facile and effective procedure for fabricating and functionalizing gold nanoaperture arrays, we have generated a microfluidic device that can enable powerful new smF experiments of weakly interacting biological systems that were previously impracticable with microscopy techniques such as TIRF. We have demonstrated that our passivated nanoaperture arrays can be used to probe biological interactions under physiological concentrations of ligand biomolecules with a protein of interest, RF1; notably, straightforward extensions of these experiments enable the structural dynamics of RF1 to be characterized as it weakly interacts with ribosomes programmed with non-stop messenger RNA codons – previously impracticable smF experiments that will allow us to investigate the mechanisms governing the fidelity with which RF1 recognizes stop codons and terminates protein synthesis. Moreover, the well-documented, robust nature of the non-specific adsorption-resistance of PEG SAMs15–19 suggests that the passivation scheme presented here should be resistant to the non-specific adsorption of many other types of biomolecules. Furthermore, the plasmon-mediated fluorescence enhancements that are attainable with a variety of gold nanoaperture geometries21 are fully compatible with the surface functionalization approaches we present here – a benefit that we will attempt to exploit in future developments of the nanoaperture array design reported here.

METHODS

Nanoaperture Array Fabrication

Borosilicate coverslips (No. 1.5, VWR) were degreased in piranha solution (3:1 H2SO4:30% H2O2) for 15 min, rinsed with Milli-Q ultrapure water, sonicated for 15 min in ethanol, and then sonicated for 15 min in Milli-Q ultrapure water. Degreased coverslips were exposed to an O2 plasma for 2 minutes, and, immediately thereafter, a thin layer of Ma-N 2403 (Micro Resist Technology GmbH), was deposited with a spin-coater. Coverslip substrates were then prebaked at 90 °C for 1 minute. Next, 2.5% poly(2,3-dihydrothieno-1,4-dioxin)-poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) (Sigma-Aldrich) was filtered through a 0.2 µm Acrodisc syringe filter (VWR), deposited with a spin-coater as a conductive layer, and then prebaked at 90 °C for 5 minutes. Arrays of circles were patterned on the substrate using an FEI Sirion SEM with a 30 kV electron beam adapted with the Nanometer Pattern Generation System (JC Nabity Lithography Systems). Patterns were developed by immersion in 8.74 M acetic acid for 5 minutes, followed by mild agitation in Milli-Q ultrapure water and mild agitation in ethanol. The emergent, ~500 nm cylindrical columns were metalized with ~100 nm of gold (Kurt J. Lesker, Co.) with a 50 Å thick, optically transparent, titanium (Kurt J. Lesker, Co.) adhesion layer using electron beam deposition with an Angstrom EvoVac Deposition System. Liftoff was performed by sonication for 2 minutes in 1M KOH, yielding nanoapertures in the relief of the columns. Nanoapertures were characterized with an Agilent 8500 FE-SEM and a Digital Instruments AFM, and analyzed with ImageJ.26

Nanoaperture Functionalization

Nanofabricated substrates were cleaned with 1.5 hour-aged piranha solution (3:1 H2SO4 : 30% H2O2) and an O2 plasma. Substrates were then incubated for 12 hours in 1 mM mPEG-SH (MW = 350 g mol−1) (Nanocs Inc.) in anhydrous ethanol (Sigma), and then rinsed with ethanol and dried with N2. Substrates were then silanized for 24 hours in 100 µM solutions of biotin-PEG-Si (MW = 2000 g mol−1) and mPEGSi (MW = 3400 g mol−1) (Laysan Bio Inc.) in anhydrous toluene (Sigma) with 10 mM glacial acetic acid (Sigma), rinsed thoroughly with ethanol, Milli-Q ultrapure water, and isopropyl alcohol, and then dried with N2.

Recombinant Gene Construction

The Escherichia coli (E. coli) prfA gene encoding wildtype polypeptide chain termination factor 1 (RF1) was previously cloned into the pPROEX-HTb expression vector (Life Technologies, Inc.) downstream of an N-terminal hexa-histidine affinity purification tag and a Tev protease cleavage site; additionally, all native cysteines were removed and a single cysteine was introduced using at amino-acid position 167 with a serine-to-cysteine mutation (RF1S167C) using site-directed mutagenesis.20 Starting with this RF1S167C construct, an N-terminal enzymatic biotinylation tag (GLNDIFEAQKIEWHE) was subcloned downstream of the Tev protease cleavage site, and site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a glutamic acid-to-cysteine mutation at amino-acid position 256 (biotag-RF1S167C,E256C).

Protein Expression

RF1 proteins were overexpressed in E. coli cells, purified using affinity chromatography, Tev protease treated, and purified away from the cleaved hexa-histidine tags and Tev protease using previously published protocols.20 Briefly, electro-competent BL21(DE3) E. coli cells cotransfected with pPROEX-HTb expression vectors carrying either RF1S167C or biotag-RF1S167C,E256C, and pET-26b(+) expression vectors carrying the gene prmC – a methyltransferase that modifies RF1 – were grown under ampicillin and kanamycin selection, and RF1 protein overexpression was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were lysed with a French Press, and RF1 proteins were purified using affinity chromatography with a Ni-NTA agarose bead column. Purified RF1 proteins were subsequently incubated with hexa-histidine-tagged Tev protease overnight, and the proteolyzed RF1 proteins were purified from the cleaved hexa-histidine tags and the hexa-histidine-tagged Tev protease using a second passage through a Ni-NTA agarose bead column. biotag-RF1S167C,E256C was biotinylated (bio-RF1S167C,E256C) using recombinant E. coli BirA biotin-ligase (plasmid obtained from AddGene) that was overexpressed, purified, and used following a previously published protocol.27

Protein Labeling

Cysteine 167 in RF1S167C was reduced by incubation with 1 mM tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride at room temperature and labeled by reaction with 15× molar excess of maleimide-derivatized Cy5 (G.E. Lifesciences) using a previously published protocol.20 bio-RF1S167C,E256C was reduced and labeled following a similar protocol, but using equivalent concentrations of both maleimide-derivatized Cy3 and Cy5. Labeled RF1 proteins were purified from unreacted dyes using size-exclusion column chromatography with a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg chromatography column (GE Lifesciences), and were subsequently purified from unlabeled RF1 proteins using hydrophobic interaction column chromatography with a TSKgel Phenyl-5PW column (Tosoh Biosciences) using previously published protocols.20 The purification yielded pure, 100% Cy5-labeled RF1S167C (RF1Cy5) and pure, 100%, 1:1 stoichiometrically Cy3- and Cy5-labeled bio-RF1S167C,E256C (bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5).

Fluorescence Microscope

Nanoaperture arrays were illuminated by epi-fluorescence through a Nikon, water-immersion 60× NA=1.2 PlanApo objective using a 50 mW, 532 nm diode-pumped solid-state laser (CrystaLaser) through a 552 nm, single-edge dichroic beamsplitter (Semrock) and a downstream 533 nm (FWHM=17 nm) notch filter (Thorlabs) using a Nikon Ti-U inverted microscope. To increase incident illumination intensity, only a quarter of the field of view was illuminated; this area contained ~1000 to 4500 nanoapertures depending on the spacing employed between the nanoapertures. Fluorescence emissions were collected through the objective, and imaged through a Photometrics DV2 wavelength splitter containing a 630dcxr dichroic beamsplitter, and HQ575/40m and HQ680/50m emission filters (for Cy3 and Cy5, respectively) onto a 512 × 512 pixel Andor iXon3 897E electron-multiplying charge-coupled-device camera. Movies were recorded at a 100 ms acquisition rate without binning using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices).

Microscopy Buffers

Tris-polymix buffer (50 mM Tris-acetate (pH25 C = 7.0), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM ammonium acetate, 0.5 mM calcium acetate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5 mM putrescine, 1 mM spermidine, 15 mM magnesium acetate, and 1% (w/v) β-D-glucose). Imaging buffer (Tris-polymix buffer supplemented with 300 mg mL−1 glucose oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich), 40 mg mL−1 catalase (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM 1,3,5,7-cyclooctatetraene (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 mM p-nitrobenzyl alcohol (Fluka))

Nanoaperture Fluorescence Microscopy

Flow cells were prepared for imaging by incubation with ultrapure bovine serum albumin (Ambion) and a 50-nucleotide oligomer of random-sequence duplex DNA (IDT), and, when specified, a subsequent incubation with 1 µM streptavidin (Invitrogen) using a previously published protocol.20 bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 was diluted to the specified concentration in Tris-polymix buffer, loaded into the flow cells, incubated for 5 min at room temperature, and untethered bio-RF1Cy3,Cy5 was removed by washing the flow cells with 200 µL of Tris-polymix buffer. Immediately prior to imaging, flow cells were washed and filled with Imaging buffer, and, when specified, various concentrations of RF1Cy5.

Data Processing

All analysis was performed with Python using NumPy and SciPy,28 Matplotlib,29 and the Python Imaging Library. Individual, Cy3 or Cy5 intensity versus time trajectories were constructed by selecting those pixels on the Cy3 half of the initial frame with intensities exceeding three standard deviations of the mean pixel intensity, clustering neighboring pixels into regions, calculating the center of mass (COM) of each region, and mapping those COM coordinates onto the Cy5 half of the frame when applicable. The intensity of a region in each frame of a movie was then obtained by summing the four pixels neighboring the region COM, linearly scaled by distance to the COM, such that the total pixel area employed in the sum was one pixel. The x- and y- coordinates for each region COM were drift-corrected in each frame of each movie by the drift of the COM of the entire illumination profile in that movie.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank J. Abramson and A. Gondarenko for thoughtful discussion on this technique, members of the Gonzalez group for their comments on the manuscript, and A. Olivo for managing the Gonzalez lab. This work was supported by an ACS Research Scholar Grant (RSG GMC-117152), and an NIH-NIGMS grant (R01 GM084288). We gratefully acknowledge the support of the CEPSR Clean Room at Columbia University. C.D.K. was supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science Graduate Fellowship Program (DOE SCGF), made possible in part by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, administered by ORISE-ORAU under contract no. DE-AC05-06OR23100, and by Columbia University’s NIH Training Program in Molecular Biophysics (T32-GM008281).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Flow cell construction. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

J.H., S.W., and R.L.G. conceived the project; M.P. designed the basic passivation scheme; all authors contributed to the intellectual development of the project; D.K.P. performed the cloning and mutagenesis of RF1; C.D.K. performed the nanofabrication, surface passivation, RF1 sample preparation, and microscopy; C.D.K. and R.L.G. wrote the manuscript with input from M.P., D.K.P., and S.W; all authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Fersht AR. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. New York: W.H. Freeman and Co.; 1999. pp. 293–368. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinoco I, Gonzalez RL. Biological Mechanisms, One Molecule at a Time. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1205–1231. doi: 10.1101/gad.2050011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levene MJ, Korlach J, Turner SW, Foquet M, Craighead HG, Webb WW. Zero-Mode Waveguides for Single-molecule Analysis at High Concentrations. Science. 2003;299:682–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1079700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ha T, Enderle T, Ogletree DF, Chemla DS, Selvin PR, Weiss S. Probing the Interaction Between Two Single Molecules: Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Between a Single Donor and a Single Acceptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:6264–6268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betzig E, Patterson GH, Sougrat R, Lindwasser OW, Olenych S, Bonifacino JS, Davidson MW, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hess HF. Imaging Intracellular Fluorescent Proteins at Nanometer Resolution. Science. 2006;313:1642–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.1127344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rust MJ, Bates M, Zhuang X. Sub-Diffraction-Limit Imaging by Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (STORM) Nat. Methods. 2006;3:793–795. doi: 10.1038/nmeth929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.English BP, Min W, Oijen AM van, Lee KT, Luo G, Sun H, Cherayil BJ, Kou SC, Xie XS. Ever-Fluctuating Single Enzyme Molecules: Michaelis-Menten Equation Revisited. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:87–94. doi: 10.1038/nchembio759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Funatsu T, Harada Y, Tokunaga M, Saito K, Yanagida T. Imaging of Single Fluorescent Molecules and Individual ATP Turnovers by Single Myosin Molecules in Aqueous Solution. Nature. 1995;374:555–559. doi: 10.1038/374555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nie S, Chiu D, Zare R. Probing Individual Molecules with Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy. Science. 1994;266:1018–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.7973650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korlach J, Marks PJ, Cicero RL, Gray JJ, Murphy DL, Roitman DB, Pham TT, Otto Ga, Foquet M, Turner SW. Selective Aluminum Passivation for Targeted Immobilization of Single DNA Polymerase Molecules in Zero-Mode Waveguide Nanostructures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:1176–1181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710982105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uemura S, Aitken CE, Korlach J, Flusberg BA, Turner SW, Puglisi JD. Real-Time tRNA Transit on Single Translating Ribosomes at Codon Resolution. Nature. 2010;464:1012–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature08925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sameshima T, Iizuka R, Ueno T, Wada J, Aoki M, Shimamoto N, Ohdomari I, Tanii T, Funatsu T. Single-Molecule Study on the Decay Process of the Football-Shaped GroEL-GroES Complex Using Zero-Mode Waveguides. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:23159–23164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eid J, Fehr A, Gray J, Luong K, Lyle J, Otto G, Peluso P, Rank D, Baybayan P, Bettman B, et al. Real-Time DNA Sequencing from Single Polymerase Molecules. Science. 2009;323:133–138. doi: 10.1126/science.1162986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schomburg I, Chang A, Placzek S, Söngen C, Rother M, Lang M, Munaretto C, Ulas S, Stelzer M, Grote A, et al. BRENDA in 2013: Integrated Reactions, Kinetic Data, Enzyme Function Data, Improved Disease Classification: New Options and Contents in BRENDA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D764–D772. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mrksich M, Whitesides GM. Using Self-Assembled Monolayers to Understand the Interactions of Man-Made Surfaces with Proteins and Cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1996;25:55–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Love JC, Estroff LA, Kriebel JK, Nuzzo RG, Whitesides GM. Self-Assembled Monolayers of Thiolates on Metals as a Form of Nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1103–1169. doi: 10.1021/cr0300789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palma M, Abramson JJ, Gorodetsky AA, Nuckolls C, Sheetz MP, Wind SJ, Hone J. Controlled Confinement of DNA at the Nanoscale: Nanofabrication and Surface Bio-Functionalization. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;749:169–185. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-142-0_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palma M, Abramson JJ, Gorodetsky AA, Penzo E, Gonzalez RL, Sheetz MP, Nuckolls C, Hone J, Wind SJ. Selective Biomolecular Nanoarrays for Parallel Single-Molecule Investigations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:7656–7659. doi: 10.1021/ja201031g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mrksich M, Whitesides G. Using Self-Assembled Monolayers That Present Oligo(ethylene glycol) Groups To Control the Interactions of Proteins with Surfaces. In. Poly(ethylene glycol); American Chemical Society. 1997;Vol. 680:23–361. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sternberg SH, Fei J, Prywes N, McGrath KA, Gonzalez RL. Translation Factors Direct Intrinsic Ribosome Dynamics During Translation Termination and Ribosome Recycling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:861–868. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenger J, Géard D, Dintinger J, Mahboub O, Bonod N, Popov E, Ebbesen TW, Rigneault H. Emission and Excitation Contributions to Enhanced Single Molecule Fluorescence by Gold Nanometric Apertures. Opt. Express. 2008;16:3008. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.003008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Géard D, Wenger J, Bonod N, Popov E, Rigneault H, Mahdavi F, Blair S, Dintinger J, Ebbesen T. Nanoaperture-Enhanced Fluorescence: Towards Higher Detection Rates with Plasmonic Metals. Phys. Rev. B. 2008;77:045413. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owens TM, Nicholson KT, Banaszak Holl MM, Süer S. Formation of Alkylsilane-Based Monolayers on Gold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6800–6801. doi: 10.1021/ja025755f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha T, Rasnik I, Cheng W, Babcock HP, Gauss GH, Lohman TM, Chu S. Initiation and Re-Initiation of DNA Unwinding by the Escherichia Coli Rep Helicase. Nature. 2002;419:638–641. doi: 10.1038/nature01083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanchard SC, Kim HD, Gonzalez RL, Puglisi JD, Chu S. tRNA Dynamics on the Ribosome During Translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:12893–12898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403884101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howarth M, Ting AY. Imaging Proteins in Live Mammalian Cells with Biotin Ligase and Monovalent Streptavidin. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:534–545. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliphant TE. Python for Scientific Computing. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007;9:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter JD. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007;9:90–95. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.