Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) slopes prior to dialysis initiation with cause-specific mortality following dialysis initiation.

Patients and Methods

In this retrospective cohort study of 18,874 United States veterans who had transitioned to dialysis from October 1, 2007, through September 30, 2011, we examined the association of pre-end-stage renal disease (ESRD) eGFR slopes with all-cause, cardiovascular, and infection-related mortality during the post-ESRD period over a median follow-up of 2.0 years (interquartile range; 1.1–3.2 years). Associations were examined using Cox models with adjustment for potential confounders.

Results

Prior to transitioning to dialysis, 4,485 (23.8%), 5,633 (29.8%), and 7,942 (42.1%) patients experienced fast, moderate, and slow eGFR decline, respectively, and 814 (4.3%) had increasing eGFR (defined as eGFR slopes of <−10, −10 to <−5, −5 to <0, and ≥0 mL/min/1.73 m2/year). During the study period, a total of 9,744 all-cause, 2,702 cardiovascular, and 604 infection-related deaths were observed. Compared with patients with slow eGFR decline, those with moderate and fast eGFR decline had a higher risk of all-cause (adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: 1.06; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00–1.11 and HR: 1.11; 95%CI 1.04–1.18, respectively) and cardiovascular mortality (HR: 1.11; 95%CI 1.01–1.23 and HR: 1.13; 95%CI 1.00–1.27, respectively). In contrast, increasing eGFR was only associated with higher infection-related mortality (HR: 1.49; 95%CI 1.03–2.17).

Conclusion

Rapid eGFR decline is associated with higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, and increasing eGFR is associated with higher infection-related mortality among incident dialysis patients.

INTRODUCTION

Despite numerous advances in our understanding of chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression, the incidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) remains exceedingly high. Each year, as many as 115,000 patients transition from advanced non-dialysis dependent CKD (NDD-CKD) to maintenance dialysis in the United States.1 Furthermore, patients who newly initiate dialysis treatment experience the highest mortality within the first few months after the transition to dialysis.1–3 In order to improve outcomes in this vulnerable population, intense study and dedicated efforts are needed to identify modifiable risk factors and interventions that may ameliorate the exceptionally high mortality risk of this transition period.4 At this time, the optimal approach to transitioning patients from NDD-CKD to maintenance dialysis remains unclear.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the association between change in kidney function and risk of adverse outcomes. Several studies have demonstrated strong associations between change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over one year and risk of ESRD,5,6 cardiovascular disease,7,8 and mortality5,7–10 among NDD-CKD patients. However, these studies have focused primarily on patients with relatively preserved kidney function, and only a few studies have examined the association between increasing eGFR trajectory and risk of adverse outcomes.6,11–14 Other than one study in advanced CKD patients,15 no prior studies have examined the association of change in eGFR including increasing eGFR in late-stage NDD-CKD with cause-specific mortality following dialysis initiation.

In this study, we investigated the association of eGFR slopes prior to dialysis initiation with all-cause, cardiovascular, and infection-related mortality after dialysis initiation in a national cohort of US veterans with advanced CKD transitioning to dialysis.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Study Population

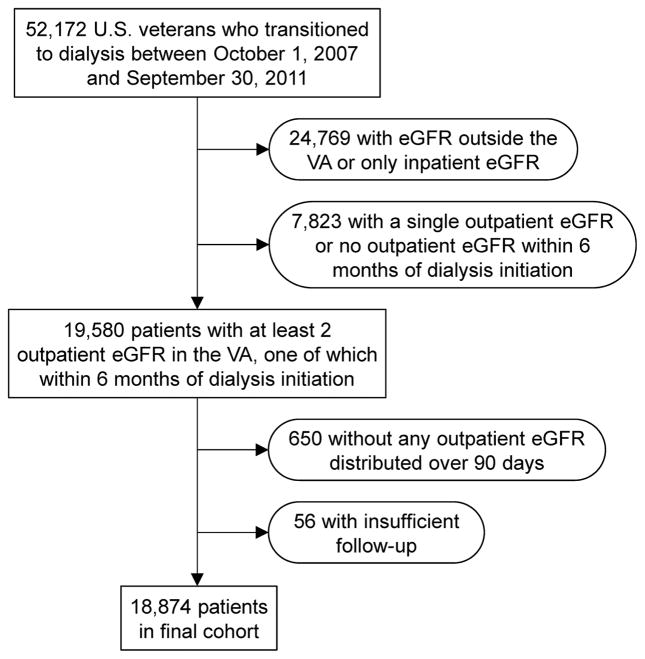

We analyzed data from the Transition of Care in CKD (TC-CKD) study, a retrospective cohort study examining US veterans transitioning to dialysis from October 1, 2007 through September 30, 2011. A total of 52,172 US veterans were identified from the US Renal Data System (USRDS)1 as an initial cohort. In this study, we used only outpatient serum creatinine measurements available from Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers because of the potential fluctuation of serum creatinine levels among sick inpatients. Therefore, patients with serum creatinine measurement outside the VA medical centers (which were not available for our analyses) or those with only inpatient serum creatinine measurements were excluded (n = 24,769). Patients were also excluded if they had less than 2 outpatient serum creatinine measurements before dialysis initiation or if they did not have any serum creatinine measurement at a VA medical center within 6 months of dialysis initiation (n = 7,823). Additional exclusions included patients without any serum creatinine measurements distributed over at least 90 days (n = 650) and those with insufficient follow-up data (n = 56). The final cohort consisted of 18,874 patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population.

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; VA, Veterans Affairs

Covariates

Data from the USRDS Patient and Medical Evidence files were used to determine patients’ demographic data including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and marital status at the time of dialysis initiation. We used the national VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) LabChem data files to extract data about serum creatinine.16 Laboratory variables except serum creatinine were collected using the Decision Support System National Data Extracts Laboratory Results file,17 and baseline values were defined as the last quarterly average of each variable before dialysis initiation or the second quarterly average from the last if the last one was not available. Data related to medication exposure were obtained from both Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Data and VA pharmacy dispensation records.18 Patients who received at least 1 dispensation of medications within 6 months of dialysis initiation were recorded as having been treated with these medications. Information about comorbidities (including the Charlson comorbidity index) at the time of dialysis initiation was extracted from the VA Inpatient and Outpatient Medical SAS Datasets,19 using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnostic and procedure codes and Current Procedural Terminology codes, as well as from VA/CMS Data. Cardiovascular disease was defined as the presence of diagnostic codes for coronary artery disease, angina, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular disease. We calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index score using the Deyo modification for administrative data sets, without including kidney disease.20

Exposure Variable

eGFR was calculated by using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation.21 Although two indices of decline in eGFR, percentage change and slope (annual change in eGFR), have been used to define CKD progression, we used eGFR slope as the main predictor for the survival models as it has been suggested to be a better predictor for mortality risk rather than percentage change.6 The eGFR slope was calculated from an ordinary least-square regression model using all available outpatient eGFR measurements starting not more than 7 years before dialysis initiation. Considering the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline which defined rapid CKD progression as a decline in eGFR of >5 mL/min/1.73 m2/year,22 we stratified pre-ESRD eGFR slopes into four a priori categories as follows: fast eGFR decline (eGFR slope <−10 mL/min/1.73 m2/year), moderate eGFR decline (eGFR slope −10 to <−5 mL/min/1.73 m2/year), slow eGFR decline (eGFR slope −5 to <0 mL/min/1.73 m2/year), and increasing eGFR (eGFR slope ≥0 mL/min/1.73 m2/year). We used the slow eGFR decline category (eGFR slope −5 to <0 mL/min/1.73 m2/year) as reference in all analyses under the assumption that mortality risk is lowest in that category. The eGFR slope was also treated as a continuous variable to examine a nonlinear association using a restricted cubic spline analysis.

Outcome Assessment

The co-primary outcomes of this study were all-cause, cardiovascular, and infection-related mortality after dialysis initiation. Death data were obtained from VA and USRDS sources.1 Cause-specific mortality data were obtained from the USRDS.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the number (percent) for categorical variables and the mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables with a normal distribution or median (interquartile range [IQR]) for those with a skewed distribution. Categorical variables were analyzed with χ2 test. Continuous variables were compared using t tests or Mann–Whitney U tests, or ANOVA, as appropriate. Survival analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazard regression to determine the association of eGFR slopes before dialysis initiation with all-cause, cardiovascular, and infection-related mortality after dialysis initiation. Patients were followed until death or other censoring events including renal transplantation, loss of follow-up, or until December 27, 2012, whichever happened first. For cause-specific mortality, the patients were followed until death or other censoring events including renal transplantation, loss of follow-up, or until October 6, 2011, whichever happened first. The effect of potential confounders was analyzed by constructing models with incremental adjustments based on a priori considerations: unadjusted (model 1); age, sex, race/ethnicity (whites, African-Americans, Hispanics, and others), and marital status (married, divorced, single, and widowed) (model 2); model 2 plus body mass index, comorbid conditions (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and Charlson comorbidity index), and last eGFR before dialysis initiation (model 3); and model 3 plus medications (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, vasodilators, loop, thiazide, and potassium-sparing diuretics, statins, active vitamin D analogs, phosphate binders [calcium acetate, sevelamer, or lanthanum], nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sodium bicarbonate, and erythropoietin stimulating agents [ESAs]) (model 4). Restricted cubic spline models were used to investigate nonlinearity in fully adjusted associations between eGFR slopes and mortality. The associations of eGFR slopes with all-cause, cardiovascular, and infection-related mortality were examined in subgroups of patients categorized by age, race, body mass index (BMI), the presence of diabetes mellitus, and last eGFR level before dialysis initiation. Interactions were formally tested for by the inclusion of interaction terms.

Of the variables included in multivariable models, data points were missing for race (2.2%), BMI (4.3%), and Charlson comorbidity index (0.01%). Information about cause of death was also missing in 47.2% of the total number of deaths in this cohort. Compared with patients with missing cause of death, those without missing cause of death were less likely to be African-American (18.8% versus 23.6%) and had a slightly higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease (57.7% versus 53.4%) and congestive heart failure (67.6% versus 62.8%) (Supplemental Table 1). There were a total of 17,660 patients (93.6% of the total study population) with complete data available for multivariable adjusted analyses. Missing values were not imputed in primary analyses, but were substituted after adding the laboratory data (serum albumin (10.6% missing), serum bicarbonate (6.5% missing), and blood hemoglobin (10.8% missing)) to the adjustment with the use of multiple imputation procedures using STATA’s “mi” set of command in sensitivity analyses. As deaths from cardiovascular or infection-related cause are competing events, we also performed sensitivity analyses to examine the association of eGFR slopes with cardiovascular and infection-related mortality using Fine and Gray competing risks proportional hazards regressions.23

The reported P values are two-sided and taken to be significant at less than 0.05 for all analyses. All of the analyses were conducted using STATA MP Version 12 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Memphis and Long Beach VA Medical Centers, with exemption from informed consent.

RESULTS

Patients’ baseline characteristics according to category of eGFR slope are presented in Table 1. Among 18,874 patients, the mean age was 69.1±11.3 years, among whom 98.2% were male, 28.6% were African-American, and 72.2% were diabetic. During the prelude pre-ESRD period to dialysis initiation, there were a median (IQR) of 18 (10, 29) serum creatinine measurements per patient, and the median (IQR) eGFR slope was −5.4 (−9.7, −2.9) mL/min/1.73 m2/year over a median (IQR) period of 4.0 (3.0, 5.2) years. Among these patients, 4,485 (23.8%), 5,633 (29.8%), and 7,942 (42.1%) experienced fast, moderate, and slow eGFR decline, respectively, whereas 814 (4.3%) patients had increasing eGFR. The median (IQR) eGFR slopes in the fast, moderate, and slow decline, and the increasing slope categories were −14.6 (−19.4, −11.9), −6.9 (−8.3, −5.9), −2.9 (−3.9, −1.9), and 1.4 (0.5, 3.2) mL/min/1.73 m2/year, respectively. Patients with fast eGFR decline were younger; were more likely to be African-Americans; had a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus and a lower prevalence of cardiovascular disease, congestive heart failure, and malignancy; had higher serum cholesterol and phosphorus; and had lower serum albumin, bicarbonate, calcium, and blood hemoglobin levels. Patients with increasing eGFR, on the other hand, were more likely to be white; had a lower prevalence of diabetes mellitus; and were less likely to use vitamin D analogs, phosphate binders, bicarbonate, and ESAs.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at the initiation of dialysis by eGFR slope categories

| Variable | All (n = 18,874) |

eGFR slope (mL/min/1.73 m2/year)

|

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast decline <−10 (n = 4,485) |

Moderate decline −10 to <−5 (n = 5,633) |

Slow decline −5 to <0 (n = 7,942) |

Increasing ≥0 (n = 814) |

|||

| Age (years) | 69.1±11.3 | 61.6±10.0 | 68.3±10.5 | 73.6±10.3 | 71.8±10.8 | <.001 |

| Gender (male) | 18,533 (98.2) | 4,376 (97.6) | 5,532 (98.2) | 7,821 (98.5) | 804 (98.8) | .002 |

| Race | <.001 | |||||

| White | 13,072 (69.3) | 2,443 (54.5) | 3,725 (66.2) | 6,242 (78.6) | 662 (81.4) | |

| African-American | 5,390 (28.6) | 1,922 (42.9) | 1,757 (31.2) | 1,565 (19.7) | 146 (18.0) | |

| Asian | 246 (1.3) | 66 (1.5) | 91 (1.6) | 88 (1.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Other | 153 (0.8) | 49 (1.1) | 56 (1.0) | 44 (0.6) | 4 (0.5) | |

| Marital status | <.001 | |||||

| Married | 10,365 (54.9) | 2,012 (44.9) | 3,029 (53.8) | 4,843 (61.0) | 481 (59.1) | |

| Divorced | 4,551 (24.1) | 1,505 (33.6) | 1,424 (25.3) | 1,465 (18.5) | 157 (19.3) | |

| Single | 1,521 (8.1) | 573 (12.8) | 456 (8.1) | 438 (5.5) | 54 (6.6) | |

| Widow | 1,958 (10.4) | 283 (6.3) | 566 (10.1) | 1,010 (12.7) | 99 (12.2) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.0±6.7 | 30.1±7.1 | 30.4±6.8 | 29.7±6.4 | 30.4±7.2 | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13,632 (72.2) | 3,536 (78.9) | 4,145 (73.6) | 5,434 (68.4) | 517 (63.5) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 18,421 (97.6) | 4,350 (97.0) | 5,535 (98.3) | 7,780 (98.0) | 756 (92.9) | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 8,972 (47.5) | 1,638 (36.5) | 2,636 (46.8) | 4,291 (54.0) | 407 (50.0) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 10,594 (56.1) | 2,213 (49.4) | 3,128 (55.5) | 4,788 (60.3) | 465 (57.1) | <.001 |

| Liver disease | 2,494 (13.2) | 873 (19.5) | 721 (12.8) | 773 (9.7) | 127 (15.6) | <.001 |

| Malignancies | 4,848 (25.7) | 837 (18.7) | 1,408 (25.0) | 2,355 (29.7) | 248 (30.5) | <.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 5 (3, 7) | 5 (3, 6) | 5 (3, 7) | 5 (3, 7) | 5 (3, 7) | <.001 |

| Medications | ||||||

| ACEI/ARB use | 9,552 (50.6) | 2,463 (54.9) | 2,880 (51.1) | 3,799 (47.8) | 410 (50.4) | <.001 |

| Diuretic use | 14,603 (77.4) | 3,599 (80.3) | 4,443 (78.9) | 6,030 (75.9) | 531 (65.2) | <.001 |

| Statin use | 12,375 (65.6) | 2,723 (60.7) | 3,792 (67.3) | 5,348 (67.3) | 512 (62.9) | <.001 |

| Vitamin D analog use | 6,136 (32.5) | 1,193 (26.6) | 1,975 (35.1) | 2,870 (36.1) | 98 (12.0) | <.001 |

| Phosphate binder usea | 6,145 (32.6) | 1,851 (41.3) | 1,967 (34.9) | 2,215 (27.9) | 112 (13.8) | <.001 |

| Bicarbonate use | 4,078 (21.6) | 1,152 (25.7) | 1,278 (22.7) | 1,554 (19.6) | 94 (11.6) | <.001 |

| ESA use | 6,257 (33.2) | 1,816 (40.5) | 2,017 (35.8) | 2,312 (29.1) | 112 (13.8) | <.001 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||||

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.4±0.6 | 3.1±0.7 | 3.4±0.6 | 3.5±0.6 | 3.5±0.7 | <.001 |

| Serum cholesterol (mg/dL) | 153.2±50.5 | 167.8±60.3 | 152.5±49.2 | 145.4±43.4 | 150.9±45.8 | <.001 |

| Serum bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 22.9±4.2 | 22.0±3.9 | 22.6±4.1 | 23.4±4.3 | 25.3±4.3 | <.001 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.5±0.6 | 4.5±0.6 | 4.5±0.6 | 4.5±0.6 | 4.3±0.5 | <.001 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 8.7±0.8 | 8.4±0.8 | 8.7±0.8 | 8.9±0.8 | 8.9±0.7 | <.001 |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dL) | 5.2±1.4 | 5.5±1.4 | 5.3±1.4 | 5.0±1.3 | 4.6±1.5 | <.001 |

| Serum ALP (U/L) | 97.8±62.9 | 103.9±75.3 | 95.6±58.2 | 95.3±57.8 | 102.9±60.5 | <.001 |

| Serum intact PTH (pg/mL) | 219 (125, 366) | 230 (136, 378) | 237 (134, 377) | 202 (115, 342) | 154 (87, 256) | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.6±1.6 | 10.2±1.5 | 10.5±1.5 | 10.9±1.6 | 11.6±2.0 | <.001 |

| Blood WBC (1000/mm3) | 7.9±3.2 | 8.0±3.0 | 7.8±3.1 | 7.8±3.4 | 8.1±3.5 | .005 |

| Serum urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 64.8±24.9 | 65.2±23.2 | 67.0±23.6 | 65.2±25.6 | 43.2±25.2 | <.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 5.0±2.5 | 5.7±2.8 | 5.3±2.5 | 4.5±2.3 | 2.7±1.9 | <.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 13.0 (9.5, 18.6) | 11.9 (8.8, 16.3) | 12.1 (9.0, 16.5) | 13.7 (10.0, 19.7) | 31.7 (18.9, 57.6) | <.001 |

| Last outpatient eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 12.9 (9.2, 19.5) | 11.6 (8.3, 16.6) | 11.9 (8.6, 16.9) | 13.9 (9.9, 21.0) | 40.9 (22.7, 66.7) | <.001 |

| Last eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 12.0 (8.5, 17.6) | 10.8 (7.7, 15.3) | 11.3 (8.0, 15.8) | 12.9 (9.1, 19.0) | 28.5 (14.5, 56.4) | <.001 |

| Time between last outpatient eGFR and dialysis initiation (days) | 32 (10, 78) | 22 (7, 60) | 27 (8, 65) | 40 (13, 89) | 75 (32, 123) | <.001 |

| Time between first and last eGFR (years) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.2) | 3.5 (2.5, 4.7) | 4.1 (3.1, 5.2) | 4.3 (3.3, 5.4) | 3.4 (2.2, 4.6) | <.001 |

| eGFR slope (mL/min/1.73 m2/year) | −5.4 (−9.7, −2.9) | −14.6 (−19.4, −11.9) | −6.9 (−8.3, −5,9) | −2.9 (−3.9, −1.9) | 1.4 (0.5, 3.2) | <.001 |

| Number of serum creatinine measurement | 18 (10, 29) | 17 (10, 27) | 19 (11, 31) | 18 (10, 30) | 10 (5, 17) | <.001 |

Note: Data are presented as number (percentage), mean ± standard deviation, or median (interquartile range).

Phosphate binders include calcium acetate, sevelamer, or lanthanum.

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; BP, blood pressure; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ESA, erythropoietin stimulating agent; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; WBC, white blood cell count.

During a median follow-up of 2.0 years (IQR, 1.1, 3.2 years; total time at risk, 41,027 patient-years [PYs]) following dialysis initiation, a total of 9,744 all-cause deaths occurred (mortality rate = 237.5/1000 PYs; 95% confidence interval [CI], 232.8–242.3), including 2,702 deaths (mortality rate = 65.9/1000 PYs; 95%CI, 63.4–68.4) and 604 deaths (mortality rate = 14.7/1000 PYs; 95%CI, 13.6–15.9) from cardiovascular and infection-related causes, respectively. Table 2 shows the hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95%CI for all-cause mortality according to categories of eGFR slopes using Cox proportional hazards models. In univariate analyses, compared to patients with slow eGFR decline, those with moderate or fast eGFR decline were at lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 0.81; 95%CI 0.77–0.84 and HR: 0.66; 95%CI 0.63–0.70, respectively), while those with increasing eGFR exhibited a higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 1.30; 95%CI 1.19–1.42). After multivariable adjustment for baseline covariates, decrement in eGFR slope categories was associated with a stepwise increase in risk of all-cause mortality among patients who experienced decline in eGFR (HR: 1.06; 95%CI 1.00–1.11, and HR: 1.11; 95%CI 1.04–1.18, for moderate and fast eGFR decline, respectively). The association between increasing eGFR and all-cause mortality was attenuated and no longer significant (HR: 0.97; 95%CI 0.87–1.07) after multivariable adjustment (Table 2). A similar trend was observed between eGFR slopes and risk of cardiovascular mortality (Table 3). In contrast, no significant associations were found between eGFR decline and infection-related mortality; however, increasing eGFR was associated with higher infection-related mortality (HR: 1.49; 95%CI 1.03–2.17) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Association of eGFR slopes with all-cause mortality after dialysis initiation

| eGFR slopes (mL/min/1.73 m2/year) | Model 1

|

P | Model 2

|

P | Model 3 | P | Model 4

|

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Increasing (≥0) | 1.30 (1.19–1.42) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.23–1.47) | <.001 | 0.96 (0.87–1.06) | .44 | 0.97 (0.87–1.07) | .55 |

| Slow decline (−5 to <0) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Moderate decline (−10 to <−5) | 0.81 (0.77–0.84) | <.001 | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | .30 | 1.06 (1.00–1.11) | .04 | 1.06 (1.00–1.11) | .03 |

| Fast decline (<−10) | 0.66 (0.63–0.70) | <.001 | 1.11 (1.05–1.18) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.05–1.19) | <.001 | 1.11 (1.04–1.18) | .001 |

Note: Data are adjusted for the following covariates: model 1: unadjusted; model 2: age, sex, race/ethnicity, and marital status; model 3: model 2 plus body mass index, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, Charlson comorbidity index, and last eGFR; model 4: model 3 plus medications.

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR; hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Table 3.

Association of eGFR slopes with cardiovascular and infection-related mortality after dialysis initiation

| eGFR slopes (mL/min/1.73 m2/year) | Cardiovascular

|

P | Infection-related

|

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |||

| Increasing (≥0) | 1.13 (0.93–1.37) | .21 | 1.49 (1.03–2.17) | .04 |

| Slow decline (−5 to <0) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Moderate decline (−10 to <−5) | 1.11 (1.01–1.23) | .03 | 1.08 (0.88–1.33) | .48 |

| Fast decline (<−10) | 1.13 (1.00–1.27) | .04 | 1.18 (0.92–1.51) | .18 |

Note: Data are adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, Charlson comorbidity index, last eGFR, and medications.

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR; hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

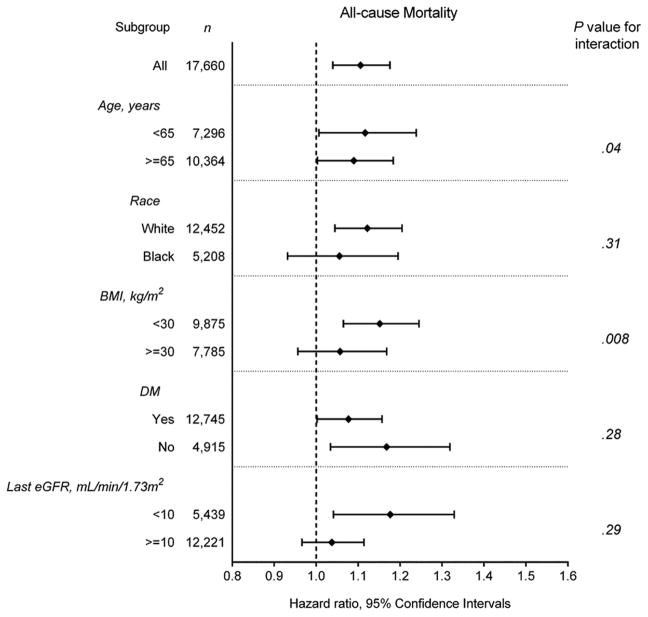

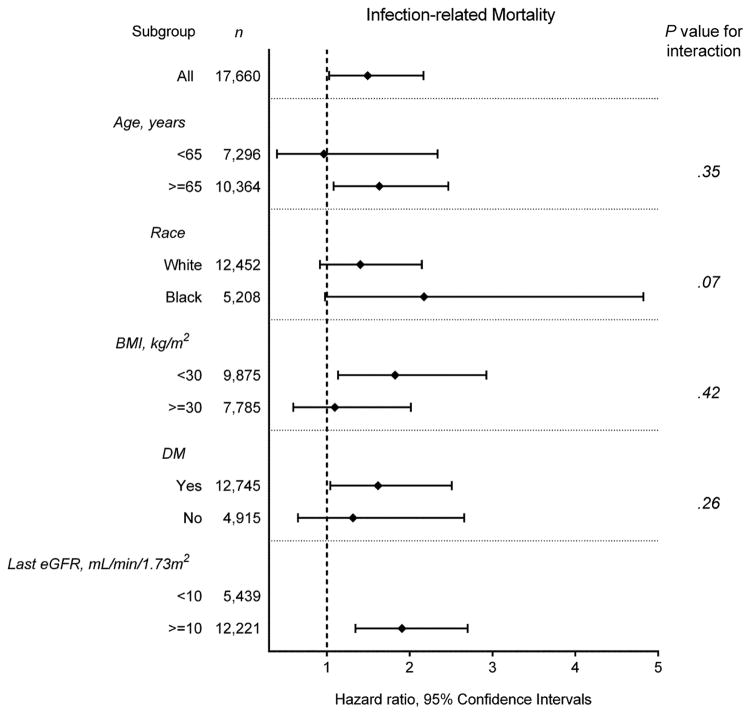

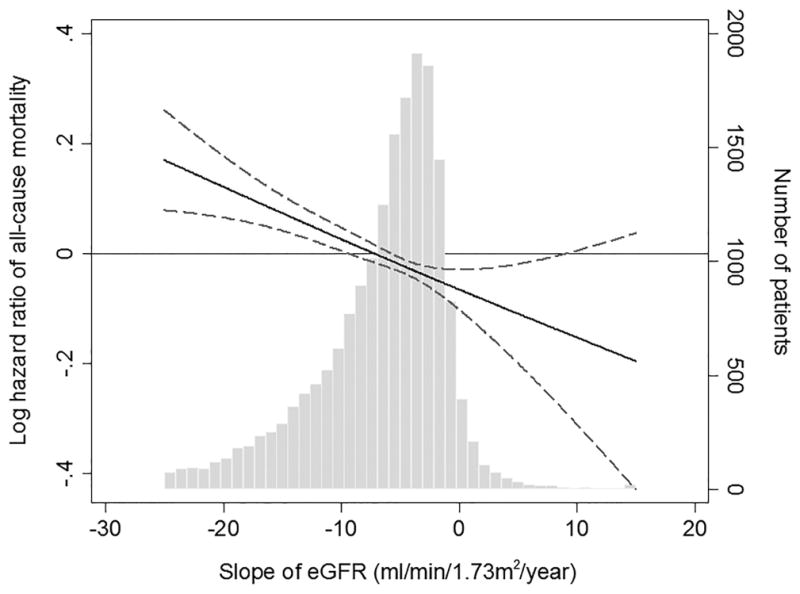

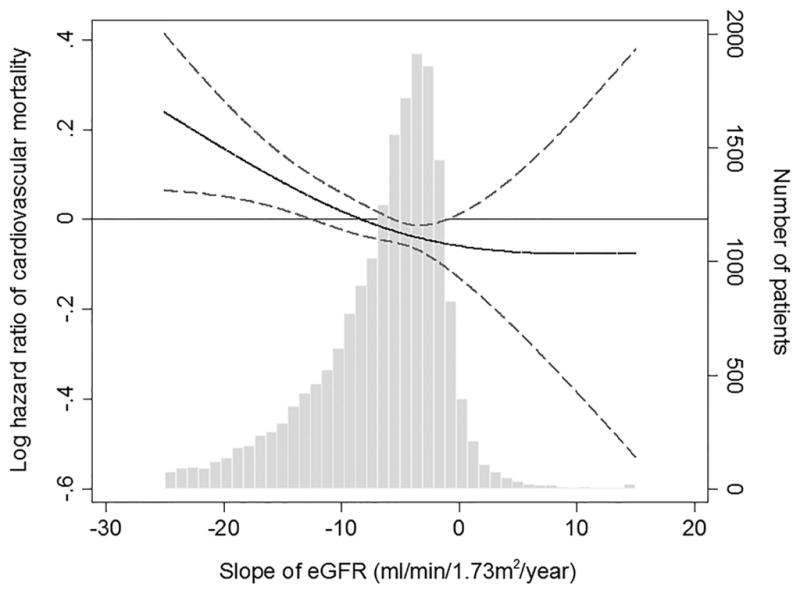

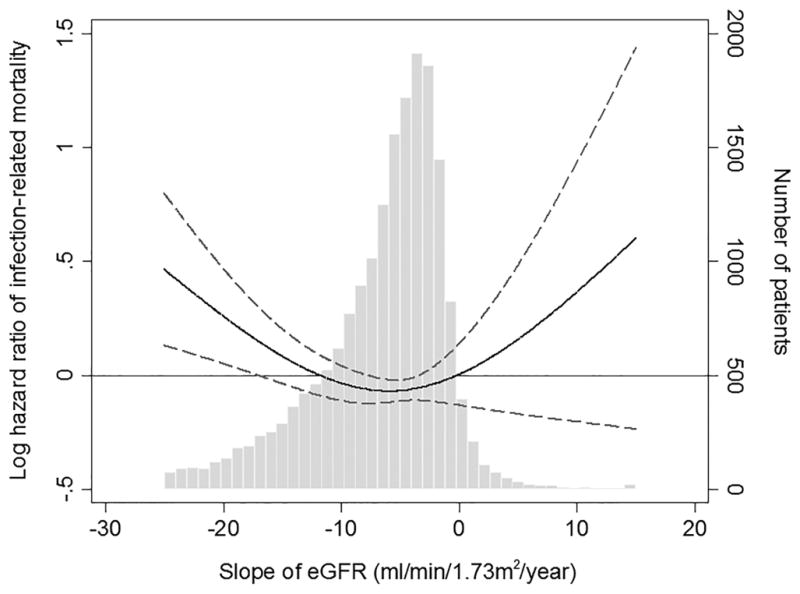

Figure 2 shows the fully adjusted association of eGFR slope as a continuous variable with the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and infection-related mortality. There was a linear association of eGFR slope with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, with higher mortality seen in those with faster eGFR decline (Figure 2A–B); whereas, a U-shaped association was observed between eGFR slope and infection-related mortality (Figure 2C). The association of faster eGFR decline with higher all-cause mortality was present in most of the examined subgroups, and similar trends, albeit without reaching statistical significance, were present for cardiovascular mortality (Figure 3A–B). The association of increasing eGFR with infection-related mortality was stronger among patients age 65 years or older, those with BMI less than 30 kg/m2, and those with diabetes mellitus, although a statistically significant interaction was not detected (Figure 3C).

Figure 2.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) of post-ESRD (A) all-cause, (B) cardiovascular, and (C) infection-related mortality associated with pre-ESRD eGFR slopes in Cox model using restricted cubic splines, adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, Charlson comorbidity index, last eGFR, and medications. The bars represent the number of patients with eGFR slope levels grouped in increments of 1 mL/min/1.73 m2/year.

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

Figure 3.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) of (A) all-cause and (B) cardiovascular mortality associated with fast eGFR decline and (C) infection-related mortality associated with increasing eGFR, compared respectively to slow eGFR decline, overall and in selected subgroups.

Models were adjusted for adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, Charlson comorbidity index, last eGFR, and medications.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

Results of analyses in which imputed values for missing variables were used yielded similar results (Supplemental Table 2). Competing risks analyses also showed similar trends of association between eGFR slope and cardiovascular and infection-related mortality (Supplemental Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort study of 18,874 patients transitioning to dialysis, we examined the association of eGFR slopes in late-stage NDD-CKD with all-cause, cardiovascular, and infection-related mortality following dialysis initiation. Compared with slow eGFR decline, both moderate and fast eGFR decline were associated with higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Interestingly, a small proportion of patients (4.3%) experienced increasing eGFR prior to transitioning to dialysis, and these patients experienced significantly higher infection-related mortality.

Previous studies have identified several factors prognosticating survival of ESRD patients; however, the impact of pre-ESRD conditions on post-ESRD outcomes in patients transitioning to dialysis remains unclear, largely because of the limitation of registry data that lacks most core data prior to dialysis initiation. With regard to the change in eGFR, studies have consistently demonstrated that one-year change in eGFR is strongly related to the risks of ESRD,5,6 cardiovascular disease,7,8 and mortality5,7–10 among NDD-CKD patients. Recently, not only declining eGFR but also increasing eGFR has been shown to be independently associated with higher mortality.6,11–14 Perkins et al.12 examined the effect of rate of eGFR decline on survival of 15,465 NDD-CKD patients receiving primary care at a single institution, and reported 84% and 42% increases in mortality for those with declining (−4.8 mL/min/1.73 m2/year) and increasing eGFR (3.5 mL/min/1.73 m2/year), respectively, compared with those with stable eGFR. Similarly, in a community-based cohort of 529,312 adults in Canada, Turin et al.14 reported that, compared with patients with stable eGFR, both decline in eGFR (≤−5 mL/min/1.73 m2/year) and increase in eGFR (≥5 mL/min/1.73 m2/year) were independently associated with higher mortality (HR 1.52 and 2.20, respectively). These studies have focused largely on the association of change in eGFR with risk of adverse outcomes among patients with relatively preserved kidney function. To our knowledge, there are only a few studies which described the association of change in eGFR with mortality after dialysis initiation. O’Hare et al.15 identified 4 distinct trajectories of eGFR during the 2-year period before dialysis initiation in CKD patients transitioning to dialysis, and demonstrated that those with more rapid loss of eGFR were at higher risk for death during the first year after initiation. Onuigbo et al.24 investigated an incident hemodialysis cohort at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, between 2001 and 2013, and reported the newly described syndrome of rapid onset ESRD (SORO-ESRD) following acute kidney injury (AKI), which was related to subsequent cardiovascular mortality with high rates of dialysis catheter use.25 In these studies, however, no information has been provided on patients with increasing eGFR and on the association of change in eGFR with different causes of death.

Our study is the first to examine eGFR slopes including both declining and increasing slopes among advanced CKD patients transitioning to dialysis, and the first to provide evidence on the association of eGFR slopes with post-ESRD cause-specific mortality. Several causal mechanisms underlying the association between eGFR decline and increased mortality have been implicated in previous studies. The worsening of kidney function could be a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, or oxidative stress,26 which contributes to increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Other potential pathways that could mediate this association include the activation of the renin-angiotensin system, blood pressure dysregulation, disordered bone and mineral metabolism, and chronic inflammation.8,27,28 In addition, worsening kidney function in patients with advanced CKD may lead to decreased appetite, decreased physical function, and overall frailty,9,29,30 which may indirectly contribute to increased risk of mortality among these patients. It should be noted that patients who experienced more rapid decline in eGFR are likely to die before reaching ESRD;9 and hence, some of the observed differences in baseline characteristics across eGFR slope categories could be explained by immortal time bias in this study. For instance, compared to patients with slow eGFR decline, patients who experienced fast eGFR decline but survived to the point of initiating dialysis were younger and had lower prevalence of cardiovascular disease and congestive heart failure; nevertheless, those patients were still at a higher risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

As previously reported,6,11–14 increasing eGFR is also associated with excess mortality in NDD-CKD patients. We observed a similar association, and also provided additional information on increasing eGFR; that is, increasing eGFR associates with higher infection-related mortality. The mechanisms underlying the higher infection-related mortality seen in patients with increasing eGFR remain speculative. The finding of increasing eGFR may be attributable to a decline in serum creatinine generation as a consequence of loss of muscle mass associated with chronic debilitating conditions.11,31 Although we did not measure nutritional status and muscle mass in a time-dependent fashion, the almost identical levels of mean BMI across eGFR categories and the lower level of mean serum creatinine in increasing eGFR categories at baseline might reflect loss of lean body mass accompanied by fluid gain in patients with increasing eGFR. Muscle wasting may lead to the emergence of circulating actin that can consume plasma gelsolin which has salutary and protective actions,32 through inactivation of bioactive lipid mediators including lysophosphatidic acid,33 lipopolysaccharide endotoxin,34 and platelet-activating factor.35 Recent evidence indicates that low level of plasma gelsolin is associated with higher mortality in dialysis patients,36 potentially because of impaired antimicrobial defenses induced by low levels of gelsolin.37 These underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms could explain the association between increasing eGFR and higher infection-related mortality. Interestingly, we found a significantly lower percentage of use for certain medications such as vitamin D analogs, phosphate binders, bicarbonate, and ESAs that are typically associated with more advanced CKD among patients with increasing eGFR; which suggest that these patients may indeed have had less advanced CKD, and perhaps started dialysis due to AKI events during a hospitalization immediately preceding dialysis initiation. These AKI events preceding dialysis initiation and underlying chronic illness could also serve as a potential explanation for the observed association. Furthermore, their strong associations observed in the subgroups of patients aged 65 years or older, with BMI less than 30 kg/m2, and with diabetes mellitus, all of which could increase infectious risk in CKD patients may also support the explanation for this association.

This study must be interpreted in light of several limitations. Our study was observational, and hence, the results do not allow us to infer causality but merely associations. About half of the patients in the initial cohort were excluded because their outpatient serum creatinine levels were not measured in VA medical centers. Most of our patients consisted of male United States veterans; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to women or the general United States population. Kidney function was not measured using a gold standard method, but estimated using the creatinine-based Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation,21 which can be affected by several non-GFR factors. Nevertheless, its widespread use affords clinical applicability to our results. Given that inpatient eGFR measurements were excluded to avoid the effects of potential hospital-acquired AKI, the influence of fluctuation in eGFR over time related to community-acquired AKI on eGFR slopes was not completely eliminated in this study. We adjusted our analyses for a variety of important covariates as potential confounders, but we cannot eliminate the possibility of unmeasured confounders, such as proteinuria, muscle mass, and changes in volume status, which might affect eGFR slopes over time.

In conclusion, compared with slow eGFR decline, more rapid eGFR decline and increasing eGFR were associated with higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and infection-related mortality, respectively, following dialysis initiation independent of comorbid conditions and other known risk factors at baseline. These findings highlight the importance of the change in eGFR on the risk for post-ESRD mortality and suggest that the eGFR slope is an additional predictor of mortality among incident dialysis patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This study is supported by grant 5U01DK102163 from the National Institute of Health (NIH) to CPK and KKZ, and by resources from the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). Support for VA/CMS data is provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development, VA Information Resource Center (Project Numbers SDR 02-237 and 98-004).

CPK and KKZ are employees of the Department of Veterans affairs. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. The results of this paper have not been published previously in whole or part.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CMS

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESA

erythropoietin stimulating agent

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- HR

hazard ratio

- IQR

interquartile range

- NDD

non-dialysis dependent

- PY

patient-year

- USRDS

United States Renal Data System

- VA

Veterans Affairs

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2014 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson BM, Zhang J, Morgenstern H, et al. Worldwide, mortality risk is high soon after initiation of hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2014;85(1):158–165. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradbury BD, Fissell RB, Albert JM, et al. Predictors of early mortality among incident US hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(1):89–99. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01170905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhee CM, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Transition to dialysis: controversies in its timing and modality [corrected] Seminars in dialysis. 2013;26(6):641–643. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turin TC, Coresh J, Tonelli M, et al. Short-term change in kidney function and risk of end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(10):3835–3843. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coresh J, Turin TC, Matsushita K, et al. Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2518–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsushita K, Selvin E, Bash LD, et al. Change in estimated GFR associates with coronary heart disease and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(12):2617–2624. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shlipak MG, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, et al. Rapid decline of kidney function increases cardiovascular risk in the elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(12):2625–2630. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009050546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rifkin DE, Shlipak MG, Katz R, et al. Rapid kidney function decline and mortality risk in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(20):2212–2218. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambers Heerspink HJ, Weldegiorgis M, Inker LA, et al. Estimated GFR decline as a surrogate end point for kidney failure: a post hoc analysis from the Reduction of End Points in Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes With the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) study and Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial (IDNT) Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(2):244–250. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Aly Z, Zeringue A, Fu J, et al. Rate of kidney function decline associates with mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(11):1961–1969. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkins RM, Bucaloiu ID, Kirchner HL, et al. GFR decline and mortality risk among patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(8):1879–1886. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00470111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turin TC, Coresh J, Tonelli M, et al. One-year change in kidney function is associated with an increased mortality risk. Am J Nephrol. 2012;36(1):41–49. doi: 10.1159/000339289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turin TC, Coresh J, Tonelli M, et al. Change in the estimated glomerular filtration rate over time and risk of all-cause mortality. Kidney Int. 2013;83(4):684–691. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Hare AM, Batten A, Burrows NR, et al. Trajectories of kidney function decline in the 2 years before initiation of long-term dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(4):513–522. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Deptartment of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service, VA Information Resource Center. VIReC Resource Guide: VA Corporate Data Warehouse. Hines, IL: VA Information Resource Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service, VA Information Resource Center. VIReC Research User Guide: Veterans Health Administration Decision Support System Clinical National Data Extracts. 2. Hines, IL: VA Information Resource Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.VA Information Resource Center (VIReC) VHA Pharmacy Prescription Data. 2. Hines, IL: VA Information Resource Center; 2008. VIReC Research User Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Medical SAS Inpatient Datasets FY2006–2007. Hines, IL: VA Information Resource Center; 2007. VIReC Research User Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levin A, Stevens PE. Summary of KDIGO 2012 CKD Guideline: behind the scenes, need for guidance, and a framework for moving forward. Kidney Int. 2014;85(1):49–61. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onuigbo MA. Syndrome of rapid-onset end-stage renal disease: a new unrecognized pattern of CKD progression to ESRD. Ren Fail. 2010;32(8):954–958. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.502608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onuigbo M, Agbasi N. Syndrome of rapid onset ESRD accounted for high hemodialysis catheter use-results of a 13-year Mayo Clinic incident hemodialysis study. Ren Fail. 2015 Sep 16;:1–6. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2015.1088336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manjunath G, Tighiouart H, Ibrahim H, et al. Level of kidney function as a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular outcomes in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2003;108(17):2154–2169. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095676.90936.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kottgen A, Russell SD, Loehr LR, et al. Reduced kidney function as a risk factor for incident heart failure: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(4):1307–1315. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shlipak MG, Stehman-Breen C, Fried LF, et al. The presence of frailty in elderly persons with chronic renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(5):861–867. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odden MC, Chertow GM, Fried LF, et al. Cystatin C and measures of physical function in elderly adults: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (HABC) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(12):1180–1189. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovesdy CP, George SM, Anderson JE, et al. Outcome predictability of biomarkers of protein-energy wasting and inflammation in moderate and advanced chronic kidney disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(2):407–414. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee PS, Waxman AB, Cotich KL, et al. Plasma gelsolin is a marker and therapeutic agent in animal sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(3):849–855. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253815.26311.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goetzl EJ, Lee H, Azuma T, et al. Gelsolin binding and cellular presentation of lysophosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(19):14573–14578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bucki R, Georges PC, Espinassous Q, et al. Inactivation of endotoxin by human plasma gelsolin. Biochemistry. 2005;44(28):9590–9597. doi: 10.1021/bi0503504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osborn TM, Dahlgren C, Hartwig JH, et al. Modifications of cellular responses to lysophosphatidic acid and platelet-activating factor by plasma gelsolin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292(4):C1323–1330. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00510.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee PS, Sampath K, Karumanchi SA, et al. Plasma gelsolin and circulating actin correlate with hemodialysis mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(5):1140–1148. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008091008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Why is protein-energy wasting associated with mortality in chronic kidney disease? Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.