Abstract

Characterizing the structural dynamics of the translating ribosome remains a major goal in the study of protein synthesis. Deacylation of peptidyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) during translation elongation triggers fluctuations of the pretranslocation ribosomal complex between two global conformational states. Elongation factor G-mediated control of the resulting dynamic conformational equilibrium helps coordinate ribosome and tRNA movements during elongation and is thus a critical mechanistic feature of translation. Beyond elongation, deacylation of peptidyl-tRNA also occurs during translation termination, and this deacylated tRNA persists during ribosome recycling. Here we report that specific regulation of the analogous conformational equilibrium by translation release and ribosome recycling factors plays a critical role in the termination and recycling mechanisms. Our results support the view that specific regulation of the global state of the ribosome is a fundamental characteristic of all translation factors and a unifying theme throughout protein synthesis.

Keywords: Ribosome, smFRET, termination, ribosome recycling, conformational dynamics

Ribosome, transfer RNA (tRNA), and translation factor structural rearrangements are hypothesized to play important mechanistic roles throughout protein synthesis. Some of the most well-characterized conformational changes of the translational machinery include the movements of tRNAs from their classical to their hybrid ribosome binding configurations, movement of the ribosomal L1 stalk from an open to a closed conformation, and the counterclockwise rotation, or ratcheting, of the small (30S) ribosomal subunit relative to the large (50S) subunit1-7. Using an L1 stalk-tRNA single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRETL1-tRNA) signal, we recently demonstrated that stochastic movements of the L1 stalk between open and closed conformations within a pretranslocation ribosomal elongation complex are coupled to the fluctuations of P-site tRNA between classical and hybrid configurations8. Taken together with ensemble intersubunit FRET data correlating the classical and hybrid tRNA binding configurations with the non-ratcheted and ratcheted conformations of the ribosomal subunits9, respectively, our smFRETL1-tRNA data suggested that the entire pretranslocation complex spontaneously and reversibly fluctuates between two major conformational states: global state 1 (GS1) and global state 2 (GS2)8 (Fig. 1a).

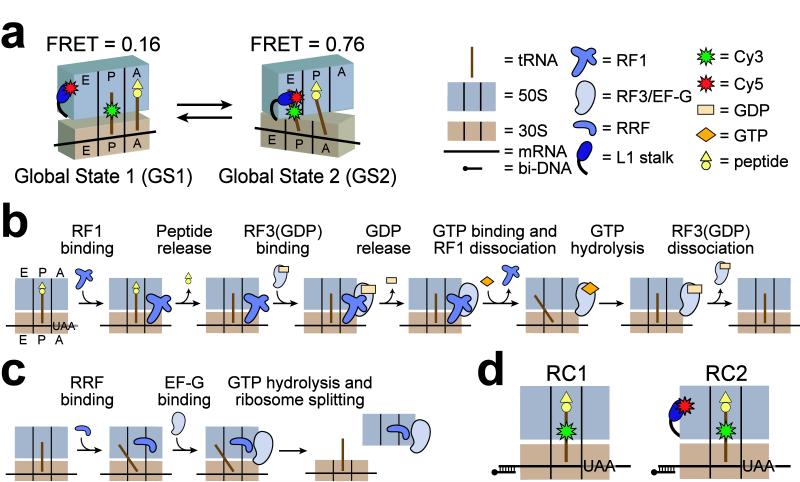

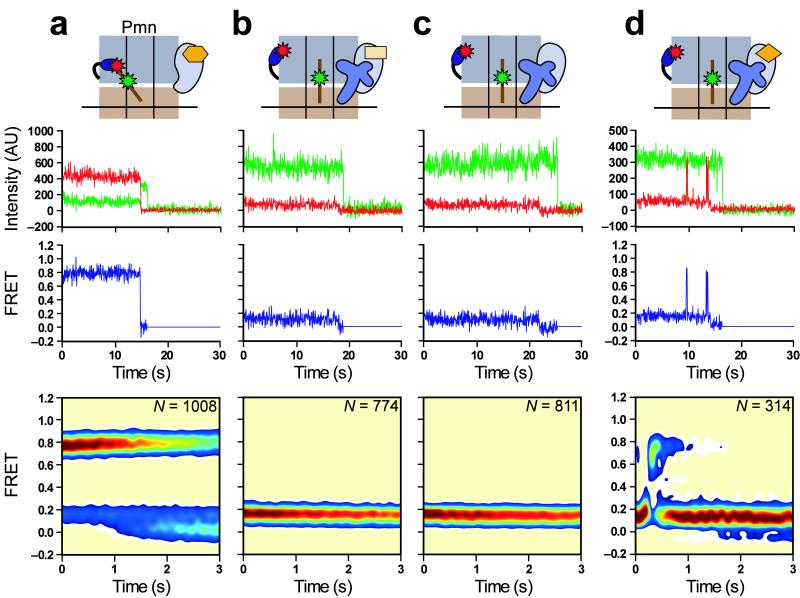

Figure 1.

Experimental model and reaction schemes for termination and recycling. (a) Our previously described smFRET signal between P-site (Cy3)tRNAPhe and L1(Cy5) demonstrated that during elongation, ribosomes exist in two global conformations: Global state 1 (GS1), encompassing a non-ratcheted ribosome, an open L1 stalk, and tRNAs bound in classical configurations; and global state 2 (GS2), encompassing a ratcheted ribosome, a closed L1 stalk, and tRNAs bound in hybrid configurations8. FRET values for GS1 and GS2 under our current conditions are shown. (b) Mechanistic model for termination. See text for details. (c) Mechanistic model for ribosome recycling. Details regarding the nucleotide binding mode of EF-G, as well as the timing of GTP hydrolysis, are not fully understood and have been omitted for clarity. Later steps of recycling involving IF3 are not depicted. (d) Cartoon diagrams of release complexes 1 (RC1) and 2 (RC2) used in this study. Cartoon representations are defined in the legend.

The essential features of our dynamic model have recently been largely validated. smFRET studies of pretranslocation complexes have reported spontaneous and reversible intersubunit rotation between two major conformations, non-ratcheted and ratcheted10, as well as fluctuations of the L1 stalk between open and closed conformations (ref. 11 and J. Fei & R.L. Gonzalez, Columbia University, unpublished data). Collectively, these studies revealed that the equilibrium constants governing the non-ratcheted⇄ ratcheted ribosome and open⇄ closed L1 stalk equilibria are closely correlated11, reinforcing the idea that these dynamic processes are coupled. Consistent with this model, two recent cryogenic electron microscopic (cryo-EM) studies used classification methods to reveal the existence of both GS1- and GS2-like conformations within a single pretranslocation sample6,7, without any detectable intermediates. Nevertheless, our GS1⇄GS2 model certainly does not incorporate all of the dynamic complexity encompassed by a ~2.5 MDa biomolecular machine. In addition, it remains entirely possible that short-lived and/or rarely-sampled intermediates have thus far eluded detection by smFRET experiments and cryo-EM reconstructions. Thus, the GS1⇄GS2 model represents the simplest dynamic model that is consistent with the available data, providing a convenient framework for investigating the dynamics of the translating ribosome.

We have previously reported that reversible transitions between GS1 and GS2 are prompted by peptidyltransfer to either an A-site aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA) or to the antibiotic puromycin8. Puromycin mimics the 3′-terminal residue of aa-tRNA12, but unlike a fully intact aa-tRNA, dissociates rapidly from the A site upon peptidyltransfer. Therefore, deacylation of P-site peptidyl-tRNA alone, regardless of A-site occupancy, is necessary and sufficient to trigger GS1⇄GS2 fluctuations. Binding of the GTPase ribosomal translocase, elongation factor G (EF-G), stabilizes GS2 (refs. 8,10), helping to control the directionality of tRNA movements during translocation. Thus, precise regulation of the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium by EF-G is a fundamental feature of translation elongation.

Beyond elongation, a deacylated tRNA also occupies the P site during translation termination and ribosome recycling, raising the possibility that regulation of the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium may be mechanistically important throughout these additional stages of protein synthesis. During termination, a stop codon in the A site of a ribosomal release complex (RC) promotes binding of a class I release factor (RF1 or RF2), which catalyzes hydrolysis of the nascent polypeptide, thereby deacylating the P-site peptidyltRNA. RF1/2 remains tightly bound to the post-hydrolysis RC, and a class II release factor (RF3, a GTPase) is required to catalyze RF1/2 dissociation13. RF3(GDP) binds to the RF1/2-bound RC, and rapid dissociation of GDP yields a high-affinity complex between nucleotide-free RF3 and the RF1/2-bound RC14. Binding of GTP to RF3 then catalyzes RF1/2 dissociation, and subsequent GTP hydrolysis leads to RF3(GDP) dissociation14, yielding a ribosomal posttermination complex (PoTC) (Fig. 1b). During ribosome recycling, the PoTC is initially recognized by ribosome recycling factor (RRF) and dissociated into its component 30S and 50S subunits by the combined action of RRF and EF-G in a GTP-dependent reaction15-17 (Fig. 1c).

Recent cryo-EM studies suggest that ribosome and tRNA structural rearrangements analogous to those observed in pretranslocation complexes (i.e. between GS1 and GS2) occur during both termination and ribosome recycling3,4,18-20, yet the GS1⇄GS2 dynamics of the post-hydrolysis RC and PoTC have not been directly investigated. Notably, the continuous presence of a deacylated P-site tRNA throughout termination and ribosome recycling strongly suggests that these ribosomal complexes possess the intrinsic capability to undergo spontaneous GS1⇄GS2 fluctuations8. Thus, determining how the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium is coupled to the activities of release and ribosome recycling factors will greatly expand our understanding of the roles that conformational dynamics of the translational machinery play in the termination and ribosome recycling mechanisms. Using a new RF1-tRNA smFRET (smFRETRF1-tRNA) signal, as well as our previously characterized smFRETL1-tRNA signal (Fig. 1d), here we directly investigate how RF1, RF3, and RRF influence and regulate the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium within the Escherichia coli ribosome. Together with our previous studies on elongation8, the results presented here support the view that manipulation of the global state of the ribosome is a fundamental mechanistic feature of all translation factors and a regulatory strategy that is used throughout protein synthesis.

RESULTS

Fluorescent labeling of RF1 and release complexes

We prepared L1(Cy5) ribosomes and Phe-(Cy3)tRNAPhe as previously described8. We prepared fluorescent release factor by mutagenizing E. coli RF1 to contain a single cysteine at position 167 within domain 2. Previous work has shown that this mutant RF1 demonstrates peptide release activity comparable to wild-type RF1 (ref. 21). Purified single-cysteine RF1 was reacted with Cy5-maleimide and separated from unreacted dye by gel filtration; further separation of unlabeled RF1 using hydrophobic interaction chromatography generated 100% homogeneously-labeled RF1(Cy5) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Using a standard peptide release assay, we showed that RF1(Cy5) demonstrates stop codon-dependent peptide release activity that is indistinguishable from wild-type RF1 (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Using these fluorescent reagents in our highly-purified in vitro translation system, we enzymatically prepared two RCs (Fig. 1d). RC1 comprises a wild-type ribosome, 5′-biotinylated mRNA, fMet-Phe-(Cy3)tRNAPhe in the P site, and an empty A site programmed with a UAA stop codon. We prepared RC2 identically to RC1 with the exception that L1(Cy5) ribosomes were used in place of wild-type ribosomes. For further details regarding the preparation and biochemical testing of translation components, see Methods and Supplementary Methods.

RF1 blocks GS1→GS2 transitions within a post-hydrolysis RC

RCs assembled on a biotinylated mRNA were immobilized on the surface of a streptavidin-derivatized quartz flow cell and visualized with single-molecule resolution using a total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (see Methods for further details). Incubation of surface-immobilized RC1 with 5 nM RF1(Cy5) generates steady-state smFRET versus time trajectories that sample a single FRET state centered at 0.94 ± 0.01 FRET (Fig. 2). Although our smFRET studies focus exclusively on relative distance changes, it is noteworthy that the observed 0.94 FRET value, corresponding to a distance of ~32–38 Å (assuming R0 = 50–60 Å22,23), is in reasonable agreement with the ~23 Å distance measured between the points of attachment of our fluorophores in an X-ray crystal structure of RF1 bound to an RC24. As a control, incubation of 5 nM RF1(Cy5) with an analogous complex containing a sense codon (AAA) at the A site yielded no detectable smFRET signal (data not shown). Inspection of individual trajectories (Fig. 2) reveals that the 0.94 FRET state is long-lived, with a lifetime limited only by fluorophore photobleaching (Supplementary Fig. 3). This observation demonstrates that after hydrolysis, RF1 remains stably bound to RC1, consistent with previous biochemical studies25. Surprisingly, the 0.94 FRET state undergoes no detectable fluctuations to additional FRET states within our time resolution (20 frames s−1). Given the large displacement (~40 Å) of the central-fold domain, or elbow, of the P-site tRNA during the classical→hybrid transition6, this suggests that deacylation of P-site tRNA by RF1 does not result in tRNA movements between the classical and hybrid binding configurations, a finding that would stand in stark contrast to the analogous situation in a pretranslocation elongation complex26-28. Nevertheless, we could not immediately exclude the possibility that tRNA movements might not result in an observable FRET change.

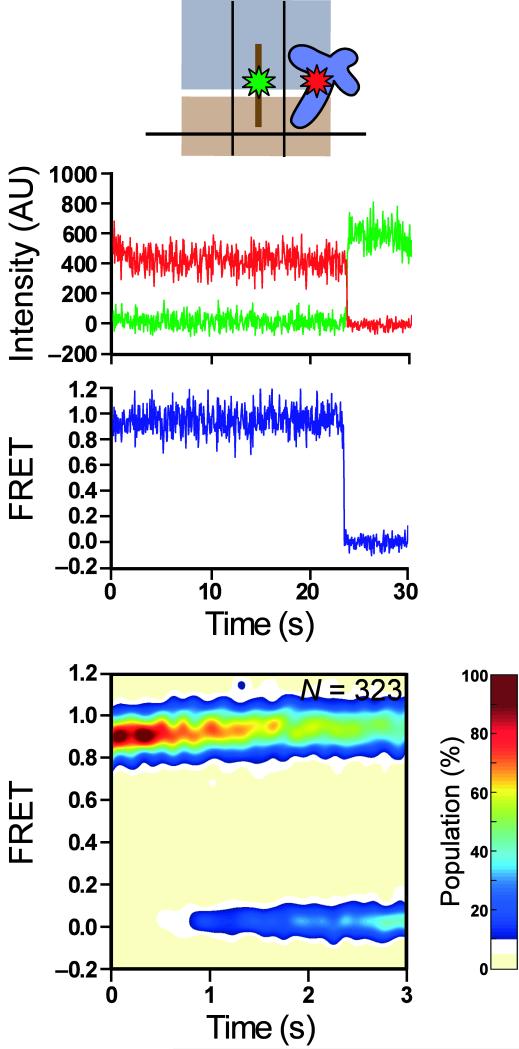

Figure 2.

RF1 binds stably to a release complex and prevents tRNA fluctuations. RC1 in the presence of 5 nM RF1(Cy5). A cartoon representation of RF1(Cy5) bound to RC1 is shown as in Fig. 1 (first row). Representative Cy3 and Cy5 emission intensities are shown in green and red, respectively (second row). The corresponding smFRET trace, ICy5/(ICy3+ICy5), is shown in blue (third row). Contour plots of the time evolution of population FRET (fourth row) are generated by superimposing the first three seconds of individual smFRET time trajectories, binning the data into 20 FRET bins and 30 time bins, normalizing the resulting data to the most populated bin in the plot, and scaling the z-axis as shown in the color bar. “N” indicates the number of traces making up the contour plot.

Therefore, in order to directly investigate the effect of RF1 on conformational dynamics of both the P-site tRNA and L1 stalk, we next monitored the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium using the smFRETL1-tRNA signal within RC2. Prior to RF1-catalyzed peptide release, the majority of RC2 trajectories (~87%) sample a single FRET state centered at 0.16 ± 0.01 FRET (Fig. 3a), consistent with our previous characterization of posttranslocation elongation complexes8, which also carry a peptidyl-tRNA at the P site and an empty A site. Of the remaining trajectories, 1% sample a single FRET state centered at 0.76 ± 0.01 FRET, reporting on GS2, and 12% exhibit fluctuations between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET; these latter two subpopulations likely represent ribosomes whose P-site peptidyl-tRNA was prematurely deacylated during RC2 preparation, thereby enabling transitions to GS2. The absolute smFRETL1-tRNA values reported in this work are slightly lower than those reported previously8 due to the use of fluorescence emission filters with slightly different transmission efficiencies.

Figure 3.

RF1 blocks GS1→GS2 transitions and stabilizes GS1. (a) RC2. Lowered FRET values for GS1 and GS2 in this work obscure the previously described broadened width of the FRET distribution caused by conformational heterogeneity of the L1 stalk in a posttranslocation complex8,11. (b) RC2 in the presence of 1 μM RF1. (c) RC2Pmn. 63% of smFRET vs. time trajectories fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET; 24% remain stably centered at 0.16 FRET, and likely represent RCs that either failed to undergo the puromycin reaction or photobleached prior to undergoing the first GS1→GS2 transition; 13% sample only 0.76 FRET, and likely represent RCs whose fluorophore(s) photobleached prior to undergoing a GS2→GS1 transition. (d) RC2Pmn in the presence of 1 μM RF1. 85% of trajectories remain stably centered at 0.16 FRET, corresponding to RF1-bound RCs; 9% fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET, and likely represent RCs to which RF1 did not bind or dissociated from transiently; 6% sample only 0.76 FRET, and likely represent RCs to which RF1 did not bind and which failed to undergo a GS2→GS1 transition prior to fluorophore photobleaching. Data in all panels are displayed as in Figure 2.

Addition of 1 μM RF1 to surface-immobilized RC2 generates no substantial change in the smFRETL1-tRNA signal (Fig. 3b), clearly demonstrating that RF1-catalyzed deacylation of P-site peptidyl-tRNA via hydrolysis does not result in GS1→GS2 transitions, in good agreement with our smFRETRF1-tRNA data. We further observed a slight shift in the relative occupancies of smFRET subpopulations, such that 98% of the trajectories now sample stable 0.16 FRET, compared to 87% in the absence of RF1 (the remaining 2% of trajectories show rare fluctuations to 0.76 FRET). Thus, even fluctuating smFRET trajectories resulting from the premature deacylation of peptidyltRNA during RC2 preparation were converted to stable 0.16 smFRET trajectories in the presence of RF1. This result suggests that RF1 binding alone can block GS1→GS2 transitions independently of the actual deacylation event.

In order to confirm these results, we next deacylated peptidyl-tRNA by pre-treating RC2 with puromycin (RC2Pmn). As expected from our previous elongation studies, the majority of RC2Pmn trajectories (~63%) fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET (Fig. 3c), reporting on spontaneous and reversible transitions between GS1 and GS2. The remaining trajectories either failed to undergo the puromycin reaction or exhibited fluorophore photobleaching directly from 0.16 or 0.76 FRET before undergoing a fluctuation (see figure legends for further subpopulation analyses); the latter observation indicates that GS1→GS2 and GS2→GS1 transition rates extracted from dwell-time analysis of these data will be slightly overestimated due to the premature truncation of the trajectories. After correcting for photobleaching kinetics and the finite experimental observation time29 (see Supplementary Methods), dwell-time analysis of RC2Pmn data yielded GS1→GS2 and GS2→GS1 transition rates (kGS1→GS2 and kGS2→GS1) of 0.52 ± 0.03 s−1 and 1.36 ± 0.03 s−1, respectively (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 4), comparable to those measured previously with similarly prepared pretranslocation elongation complexes8.

Addition of 1 μM RF1 to surface-immobilized RC2Pmn strongly perturbs the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium (Fig. 3d), such that the majority (85%) of the trajectories now exhibit stable 0.16 FRET. Indeed, addition of RF1 to RC2Pmn generates an smFRETL1-tRNA signal that is virtually indistinguishable from that observed for non-puromycin reacted RC2 in the absence or presence of RF1 (compare Fig. 3d to 3a,b). In all three cases, measurement of the actual lifetime spent in the 0.16 FRET state is limited by fluorophore photobleaching, demonstrating that intermolecular RF1-ribosome and/or intramolecular ribosome-ribosome interactions, established upon tight binding of RF1 to the post-hydrolysis RC, block the GS1→GS2 transitions that would otherwise occur spontaneously in a ribosomal complex carrying a deacylated tRNA at the P site. Thus, whereas deacylation of P-site tRNA via peptidyltransfer to A-site aa-tRNA shifts the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium towards GS2 in anticipation of EF-G8, deacylation of P-site tRNA via RF1-mediated hydrolysis locks the RC in GS1 in anticipation of RF3.

RF1 domain 1 is expendable for blocking GS1→GS2 transitions

RF1 domains 2–4 occupy the A site in a manner that is spatially analogous to a classically-bound tRNA18,24,30, whereas domain 1 protrudes out of the A site, spanning the gap between the “beak” domain of the 30S subunit and the L11 region of the 50S subunit24. Because direct contacts between RF1 domain 1 and both the 30S and 50S subunit have been observed crystallographically24,30, we wondered whether domain 1-ribosome interactions might provide the molecular basis for RF1’s ability to block GS1→GS2 transitions. To test this, we prepared an RF1 domain 1 deletion mutant (RF1Δd1) as previously described31 and generated RF1Δd1(Cy5) in the same manner as full-length RF1(Cy5). Biochemical testing confirms that RF1Δd1 and RF1Δd1(Cy5) can catalyze stop codon-dependent peptide release, albeit with slightly lower activity relative to full-length RF1 as previously reported31 (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 2).

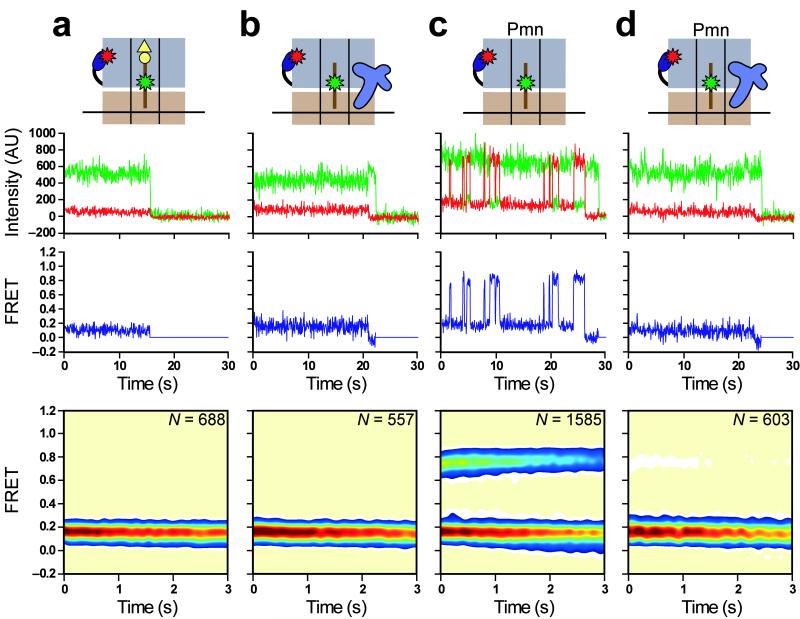

Figure 4 reports the results of RC1, RC2, and RC2Pmn experiments analogous to those reported in Figures 2 and 3, but with RF1Δd1 in place of full-length RF1. The results are virtually indistinguishable. The smFRETRF1Δd1-tRNA signal, centered at 0.93 ± 0.02 FRET, is stable and shows no evidence of fluctuations (Fig. 4a), suggesting that, analogous to full-length RF1, RF1Δd1 remains stably bound to the post-hydrolysis RC and prevents tRNA movements. As expected from this result, we find that, despite the absence of domain 1-ribosome interactions, RF1Δd1 blocks GS1→GS2 transitions upon hydrolysis (Fig. 4b) and independently of the origin of the deacylation event (Fig. 4c). Thus, our data clearly demonstrate that RF1’s ability to lock the RC in GS1 does not require domain 1.

Figure 4.

RF1 domain 1 is dispensable for RF1-mediated blocking of GS1→GS2 transitions. (a) RC1 in the presence of 5 nM RF1Δd1(Cy5). (b) RC2 in the presence of 1 μM RF1Δd1. 94% of trajectories remain stably centered at 0.16 FRET; 6% fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET. (c) RC2Pmn in the presence of 1 μM RF1Δd1. 86% of trajectories remain stably centered at 0.16 FRET; 10% fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET; 4% sample only 0.76 FRET. Data in all panels are displayed as in Figure 2.

GTP binding to RC-bound RF3 triggers the GS1→GS2 transition

Our RF1 studies demonstrate that the target for RF3-mediated RF1 dissociation is a post-hydrolysis, RF1-bound RC locked in GS1. However, a recent cryo-EM study reported the GS2-like conformation of a puromycin-reacted RC bound to RF3(GDPNP, a non-hydrolyzable GTP analog)4; this structure provides a snapshot of the post-hydrolysis RC after RF1 dissociation but before GTP hydrolysis by RF3. In order to investigate the dynamics of an analogously prepared RC, we first confirmed that our purified RF3 exhibits previously described guanine nucleotide-dependent biochemical activity14 (Supplementary Fig. 5), and then performed an experiment in which we added 1 μM RF3(GDPNP) to surface-immobilized RC2Pmn. The resulting data reveal that RF3(GDPNP) substantially alters the relative occupancies of subpopulations observed with RC2Pmn, such that the majority (73%) of smFRET trajectories now remain stably centered at 0.76 FRET (Fig. 5a). Thus, in complete opposition to RF1, the GTP-bound form of RF3 locks a post-hydrolysis RC into GS2. Dwell-time analysis of the fluctuating subpopulation of smFRET trajectories (22%) revealed kinetics that were consistent with those of isolated RC2Pmn, suggesting that this subpopulation of RC2Pmn simply did not bind RF3(GDPNP) under our conditions. Consistent with this interpretation, increasing the RF3(GDPNP) concentration causes a decrease in the occupancy of the fluctuating subpopulation while kGS1→GS2 and kGS2→GS1 remain relatively constant (Supplementary Fig. 6).

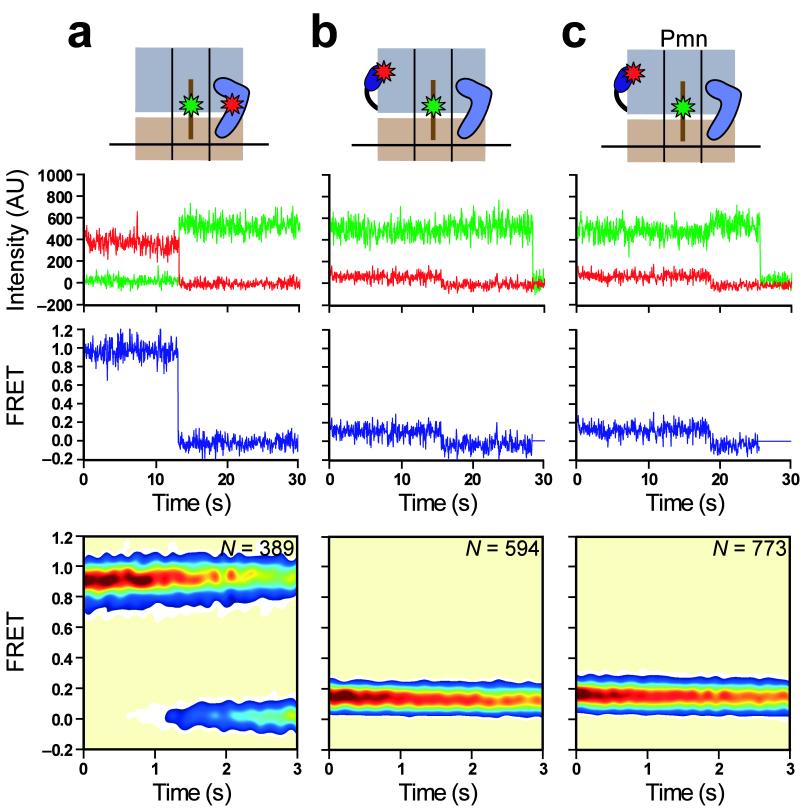

Figure 5.

RF3(GDP) interacts with an RF1-bound ribosome locked in GS1, and binding of GTP to RC-bound RF3 enables the GS1→GS2 transition. (a) RC2Pmn in the presence of 1 μM RF3(GDPNP) (GDPNP is denoted as an orange hexagon). 73% of trajectories remain stably centered at 0.76 FRET, corresponding to RF3(GDPNP)-bound RCs; 5% sample only 0.16 FRET; 22% fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET. The latter two subpopulations likely represent RCs that either failed to undergo the puromycin reaction or were photobleached prior to undergoing the first GS1→GS2 transition, or that did not bind RF3(GDPNP) and therefore spontaneously fluctuate between GS1 and GS2. This conclusion is supported by results from an RF3(GDPNP) titration (Supplementary Fig. 6). (b) RC2RF1 in the presence of 1 μM RF1 and RF3(GDP). 98% of trajectories remain stably centered at 0.16 FRET; 2% fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET. (c) RC2RF1 in the presence of 1 μM RF1 and nucleotide-free RF3. 99% of trajectories remain stably centered at 0.16 FRET; 1% fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET. (d) RC2RF1 in the presence of 1 μM RF1, RF3(GDP) and 1 mM GTP. Only those trajectories exhibiting fluctuations between GS1 and GS2 (42%) make up the time-synchronized contour plot (fourth row), generated by post-synchronizing the onset of the first GS1→GS2 event in each trajectory to time = 0.5 seconds. The remaining 58% of trajectories remain stably centered at 0.16 FRET. Data in all panels are displayed as in Figure 2.

The smFRET data suggest that the GS1→GS2 transition occurs at some point during or after binding of RF3(GDP) to the post-hydrolysis, RF1-bound RC, but before hydrolysis of GTP by RF3. We sought to further pinpoint the GS1→GS2 transition within the termination pathway by performing a set of steady-state smFRET experiments where we initially incubated surface-immobilized RC2 with 1 μM RF1 to generate RC2RF1, and subsequently incubated RC2RF1 with 1 μM RF3 in the absence or presence of the specified guanine nucleotide and 1 μM RF1. Biochemical data provide evidence that nucleotide-free RF3 forms a high-affinity complex with the RF1-bound RC14 (Supplementary Fig. 5), and so we first tested whether binding of RF3(GDP) or nucleotide-free RF3 to RC2RF1 could activate the GS1→GS2 transition. Both of these experiments generate steady-state smFRET data that is indistinguishable from data collected with RC2RF1 alone (compare Fig. 5b,c with 3b), suggesting that neither binding of RF3(GDP) to RC2RF1, RC2RF1-catalyzed exchange of GDP for exogenous GDP on RF3, nor the nucleotide-free RF3 intermediate elicit or involve the GS1→GS2 transition.

We next tested the addition of RF3(GDP) to surface-immobilized RC2RF1 in the presence of a mixture of 10 μM GDP and 1 mM GTP. Because it was performed with saturating 1 μM RF1, this experiment is expected to yield a continuously recycling termination reaction (Fig. 1b), in which binding of GTP to RC-bound RF3 catalyzes RF1 dissociation and subsequent GTP hydrolysis leads to RF3(GDP) dissociation14, thereby enabling RF1 rebinding and a new round of RF3-mediated RF1 dissociation. Interestingly, individual smFRET trajectories exhibit clear evidence of one or more excursions to GS2 (Fig. 5d), demonstrating that the GS1→GS2 transition occurs exclusively upon binding of GTP to RC-bound RF3. Transitions to GS2 are exceptionally short-lived, indicating the possibility of missing events (i.e. excursions to GS2 that are much shorter than our time resolution). Thus, dwell-time analysis provides a lower limit of kGS2→GS1 ≥ 3.7 ± 0.6 s−1 (Supplementary Fig. 7), which is almost 3-fold faster than kGS2→GS1 for RC2Pmn in the absence of RF1, RF3, and guanine nucleotide (1.36 ± 0.03 s−1). This result suggests that hydrolysis of GTP, dissociation of RF3(GDP), and/or rebinding of RF1 may modestly promote the GS2→GS1 transition.

RRF fine-tunes the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium within a PoTC

Previous biochemical characterization has demonstrated that puromycin-reacted RCs yield PoTCs that serve as natural substrates for RRF- and EF-G-catalyzed ribosome recycling32. Thus, after confirming the activity of our purified RRF in a standard ribosome splitting assay (Supplementary Fig. 8), we used RC2Pmn as a model PoTC with which to investigate the effect of RRF binding on the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium. Contrary to RF1 and RF3, we find that RRF has only modest effects on the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium, slightly stabilizing GS2 (Fig. 6a); even with a large excess of RRF over surface-immobilized RC2Pmn, the relative occupancies of smFRET subpopulations remain almost unchanged relative to RC2Pmn. As we increased the RRF concentration, the dwell time spent in the 0.76 FRET state was extended, ultimately leading to a decrease in the occupancy of the fluctuating subpopulation and an increase in occupancy of the stable 0.76 FRET subpopulation as the rate of photobleaching from the 0.76 FRET state began to limit observations of fluctuations to 0.16 FRET. However, even at concentrations as high as 50 μM RRF, individual smFRET trajectories still exhibit rare fluctuations to 0.16 FRET.

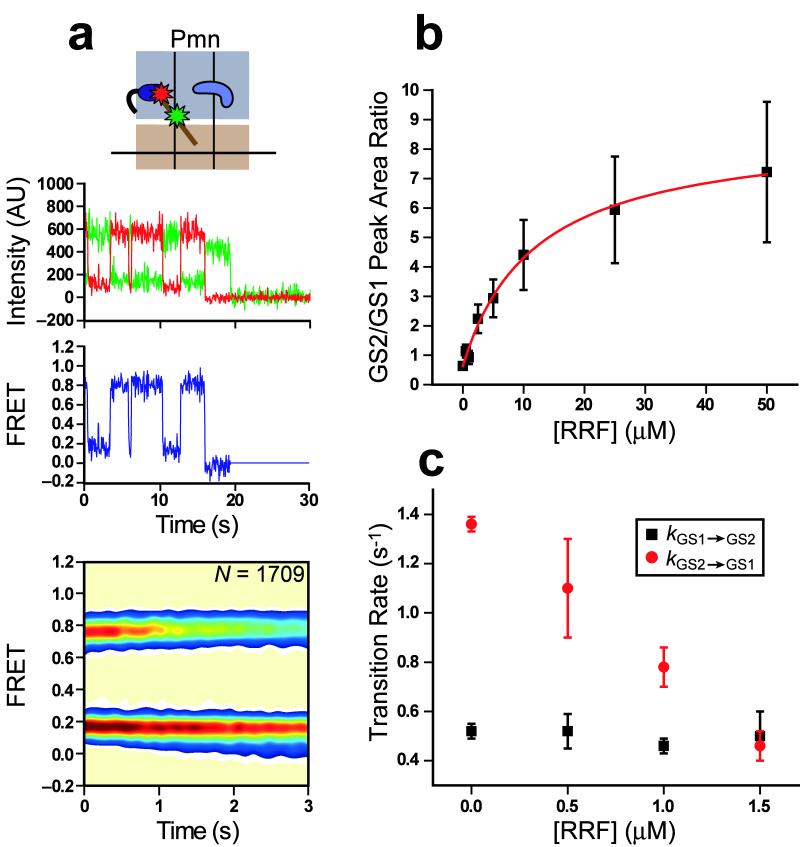

Figure 6.

RRF preferentially binds GS2 and competes with GS2→GS1 transitions within a fluctuating posttermination complex. (a) RC2Pmn in the presence of 1 μM RRF. 70% of trajectories fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET; 23% remain stably centered at 0.76 FRET; 7% sample only 0.16 FRET. For RC2Pmn data analyzed similarly, 76% fluctuate between 0.16 and 0.76 FRET, 18% remain stably centered at 0.76 FRET; 6% sample only 0.16 FRET. The slight differences between these RC2Pmn subpopulations and those reported in Figure 3c arise from automated, rather than manual, detection of strongly anti-correlated Cy3 and Cy5 intensity traces (see Supplementary Methods for details). Data are displayed as in Figure 2. (b) GS2/GS1 peak area ratio (Keq) as a function of RRF concentration. The data was fit according to the equation in the text (red line), yielding the following parameters: C = 0.6 ± 0.1, Kd,GS1 = 12 ± 2 μM and Kd,GS2 = 0.9 ± 0.3 μM (R2 = 0.99). (c) kGS1→GS2 and kGS2→GS1 as a function of RRF concentration. Error bars represent the standard deviation from at least three independent experiments.

To more quantitatively probe the subtle effect of RRF on the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium, we plotted one-dimensional smFRET histograms of the entire population of trajectories as a function of RRF concentration (Supplementary Fig 9). The areas under the peaks centered at 0.16 and 0.76 FRET report on the equilibrium populations of GS1 and GS2, respectively. From these plots, it is evident that the GS1 population decreases while the GS2 population increases as a function of increasing RRF concentration. Assuming that RRF can bind to both GS1 and GS2, a plot of the GS2/GS1 peak area ratio (Keq) vs. RRF concentration can be fit by the following binding isotherm in order to determine the equilibrium dissociation constants for RRF binding to GS1 (Kd,GS1) and GS2 (Kd,GS2)33:

where C is the GS2/GS1 peak area ratio in the absence of RRF. This analysis yields a Kd,GS2 of 0.9 ± 0.3 μM and a Kd,GS1 of 12 ± 2 μM (Fig. 6b), revealing that RRF exhibits greater than an order of magnitude tighter binding to GS2 over GS1. This result is supported by structural studies describing a clear steric clash between the binding positions of RRF and the aminoacyl-end of classically-bound tRNA at the P site within GS1 (refs. 3,20,34-37). The Kd of RRF binding to vacant ribosomes (i.e. in the absence of mRNA or tRNAs) is in the range of 0.2–0.6 μM38-40, in good agreement with the Kd we report for GS2, further indicating that RRF may interact with the GS2 conformation of the PoTC in much the same way as it does with a vacant ribosome.

In order to explore the kinetic basis for the RRF-mediated change in the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium, we determined kGS1→GS2 and kGS2→GS1 in a low RRF concentration range (0–1.5 μM), where substantial corrections for premature truncation of the trajectories due to photobleaching are not necessary. Analysis of these data clearly shows that, at RRF concentrations near Kd,GS2, kGS1→GS2 remains unchanged while kGS2→GS1 decreases linearly (Fig. 6c). The observation that kGS1→GS2 remains unchanged is consistent with the low affinity of RRF for GS1 and reveals that, at low RRF concentrations, RRF neither induces nor inhibits the GS1→GS2 transition. Instead, RRF seems to depend upon a spontaneous GS1→GS2 transition for access to the GS2 conformation of the PoTC. The decrease in kGS2→GS1 within the same RRF concentration range demonstrates that RRF binds to GS2 and inhibits GS2→GS1 transitions. The simplest model consistent with all of the data is that, at RRF concentrations near Kd,GS2, RRF rapidly binds to and dissociates from GS2, with binding directly competing with the GS2→GS1 transition. As the concentration of RRF increases, repeated RRF binding events begin to out-compete the GS2→GS1 transition, thus leading to the observed steady decrease in kGS2→GS1.

Given a Kd,GS1 of 12 ± 2 μM, it is not surprising that no appreciable effect is seen in kGS1→GS2 at RRF concentrations of 0–1.5 μM. In order to assess whether RRF might affect kGS1→GS2 at higher concentrations, we analyzed the 50 μM RRF dataset for rare excursions to GS1. Dwell-time analysis of these rare events revealed that, at 50 μM RRF, kGS1→GS2 is 1.6-fold faster than kGS1→GS2 for free RC2Pmn (0.83 ± 0.06 s−1 versus 0.52 ± 0.03 s−1, respectively). Thus, at high enough concentrations where substantial binding to GS1 becomes possible, RRF modestly promotes the GS1→GS2 transition through a yet to be determined mechanism. Collectively, our results demonstrate that the population of PoTCs found in the GS2 conformation can be tuned by regulating RRF concentration.

DISCUSSION

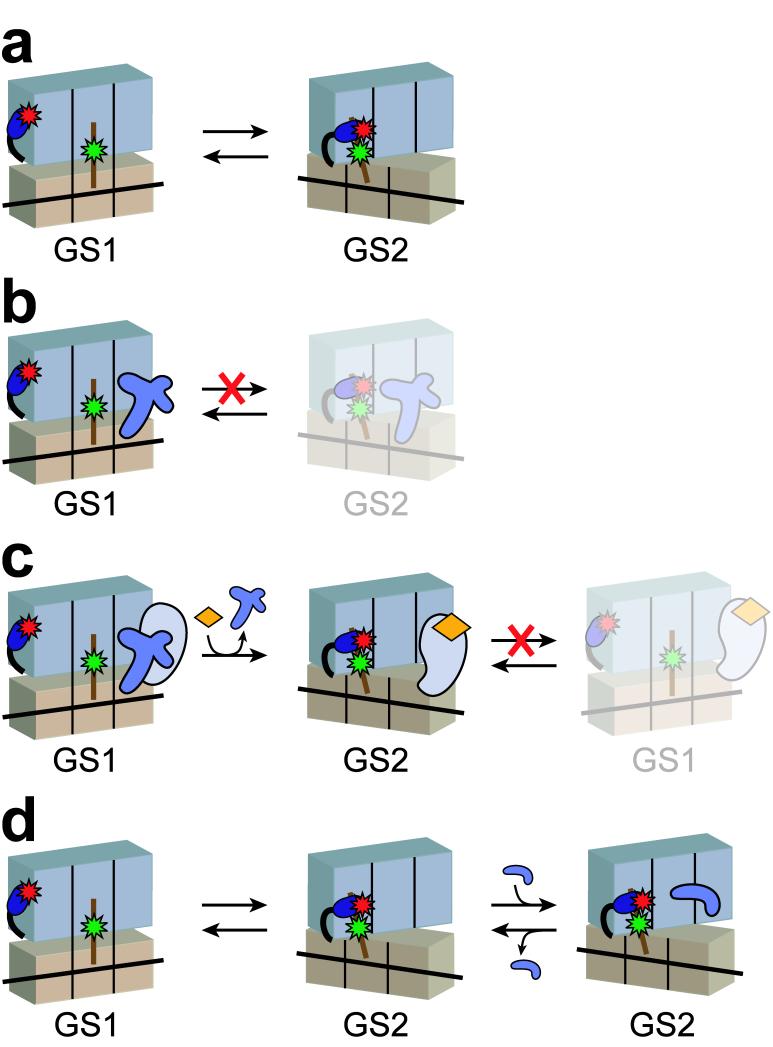

The tight binding of RF1 to a post-hydrolysis RC establishes intermolecular RF1-ribosome, and possibly intramolecular ribosome-ribosome interactions, which block GS1⇄GS2 fluctuations that are otherwise intrinsic to ribosomal complexes carrying a deacylated P-site tRNA (Fig. 7a,b). Thus, without making extensive interactions with the P-site tRNA or any contacts with the L1 stalk, RF1 successfully blocks movements of P-site tRNA from the classical to the hybrid configuration, movements of the L1 stalk from the open to the closed conformation, and presumably, the accompanying intersubunit ratcheting of the ribosome. This observation highlights the tight coupling between ribosome and tRNA dynamics and reveals that the interaction of translation factors with the ribosome can allosterically and specifically regulate the global state of the ribosome.

Figure 7.

Mechanistic model for regulation of the GS1⇄GS2 dynamic equilibrium by RF1, RF3, and RRF. (a) A post-hydrolysis release complex (RC) fluctuates stochastically between GS1 and GS2. (b) RF1 specifically binds GS1 and prevents GS1→GS2 transitions of the RC, even after deacylation of P-site tRNA. (c) RF3(GDP) initially interacts with an RF1-bound RC locked in GS1. GS1→GS2 transitions are suppressed until nucleotide-free RF3 binds GTP, which stabilizes the RC in GS2 and prevents GS2→GS1 transitions prior to GTP hydrolysis. (d) A posttermination complex, the natural substrate for RRF, fluctuates stochastically between GS1 and GS2. At concentrations near Kd,GS2, RRF preferentially binds GS2 and competes directly with the GS2→GS1 transition. At high RRF concentrations above Kd,GS1, RRF can also bind GS1 and actively promote the GS1→GS2 transition (not shown). Cartoon representations are shown as in Figure 1.

The finding that RF1Δd1 is indistinguishable from full-length RF1 in its ability to block GS1→GS2 transitions demonstrates that any potential intersubunit interactions mediated by domain 1 are not essential for blocking GS1→GS2 transitions. Thus, the mechanism through which RF1 blocks GS1→GS2 transitions remains uncharacterized. One attractive possibility is the base-stacking interaction between A1913 from helix 69 of 23S rRNA and A1493 from helix 44 of 16S rRNA, which was observed in a recent X-ray crystal structure of RF1 bound to an RC24. This contact physically connects the two subunits, is a distinctive feature of an RF1-bound RC, and might therefore play a role in preventing the GS1→GS2 transition. Future RF1, helix 69, and/or helix 44 mutations will enable testing of this hypothesis.

Our smFRET data demonstrate that the target of RF3(GDP) is a post-hydrolysis, RF1-bound RC locked in GS1, and that the intrinsic GS1→GS2 transition remains suppressed throughout the interaction of the RF1-bound RC with RF3(GDP) and nucleotide-free RF3. Indeed, the GS1→GS2 transition occurs exclusively upon binding of GTP to RC-bound RF3, which leads to RF1 dissociation and stabilization of GS2 prior to GTP hydrolysis (Fig. 7c). Our results clearly indicate that the characteristic fluctuations between GS1 and GS2 that are typically triggered by deacylation of the P-site tRNA are specifically regulated throughout the termination pathway. Nevertheless, the present data do not allow us to temporally resolve GTP binding, the GS1→GS2 transition and dissociation of RF1. Therefore, at this time we cannot distinguish between the recently proposed model for RF3 function in which binding of GTP to RC-bound RF3 actively drives the GS1→GS2 transition, indirectly leading to RF1 dissociation4, or an alternative model in which binding of GTP to RC-bound RF3 actively drives RF1 dissociation, consequently enabling the GS1→GS2 transition that can occur spontaneously in the absence of RF1. Future three- and four-wavelength experiments using fluorescently-labeled ribosomes, tRNAs, and RFs to directly observe the relative timing of GS1⇄GS2 transitions and the binding and dissociation of RFs with single-molecule resolution should allow us to resolve these mechanistic details.

As is the case during elongation and termination, the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium is specifically regulated, although more subtly, during ribosome recycling. Our smFRET data demonstrate the ability of RRF to shift the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium towards an RRF-bound GS2 conformation as a function of increasing RRF concentration. This occurs through two mechanisms. At low concentrations, RRF preferentially and transiently binds to GS2, competing directly with the GS2→GS1 transition and inhibiting kGS2→GS1 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 7d). At high concentrations, RRF can also bind directly to GS1 and modestly increase kGS1→GS2. Tunable shifting of the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium towards an RRF-bound PoTC in GS2 sets important constraints for subsequent steps of ribosome recycling. For example, the RRF-bound PoTC in GS2, which presumably serves as the substrate for EF-G-catalyzed splitting of the ribosomal subunits, is a transient species whose fractional population is a sensitive function of RRF concentration. This implies that the efficiency of ribosome recycling will be strongly dependent on RRF concentration, as has been demonstrated in vitro15,41. These results further suggest that cellular control of RRF concentrations can regulate the efficiency of ribosome recycling in vivo, which may be important for reactivating sequestered ribosomes42 and preventing unscheduled translation reinitiation events43.

The ribosome interacts with numerous translation factors throughout protein synthesis, many of which bind at partially overlapping sites and thus compete for ribosome binding. The organizing principles through which the ribosome coordinates the binding of translation factors, thus avoiding negative interference, remain an open question. Biochemical studies have shown that the absence or presence of a peptide on P-site tRNA regulates the activities of the translational GTPases44. Taken together with our previous study8, the work presented here reveals an additional level of organizational control in which the absence or presence of a peptide on the P-site tRNA controls a dynamic equilibrium involving coupled tRNA and ribosome dynamics that is uniquely recognized and manipulated by elongation, release, and ribosome recycling factors during the elongation, termination, and recycling stages of translation (Fig. 7). Thus, given the universally conserved two-subunit architecture of the ribosome, as well as the conserved ability of eukaryotic ribosomes to sample GS1- and GS2-like conformations45,46, careful regulation of the GS1⇄GS2 equilibrium likely serves as a universal principle for organizing the binding and biochemical activities of translation factors throughout protein synthesis.

METHODS

Purification of release and ribosome recycling factors

After cloning genes encoding RF1, RF1Δd1, RF3, and RRF, we overexpressed protein factors in BL21 cells, purified them using Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography, and cleaved their hexahistidine affinity tags with TEV protease. We co-overexpressed RF1 and RF1Δd1 with a plasmid-encoded copy of the PrmC gene, an N5-glutamine methyltransferase known to methylate RF1 at residue Gln235 (refs. 47,48). All purified proteins were greater than 95% pure, as evidenced by SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 1a), and we confirmed their identities by mass spectrometry. Final protein stocks were stored at −20°C in Translation Factor Buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl pH4°C = 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 50% (v/v) glycerol). Further details regarding cloning, mutagenesis, purification, Cy5-labeling, and biochemical activity assays of factors can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Ribosomal release complex formation and purification

We prepared release complexes 1 and 2 (RC1 and RC2) in Tris-polymix buffer (50 mM Tris-OAc, pH25°C = 7.0, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM NH4OAc, 0.5 mM Ca(OAc)2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5 mM putrescine, and 1 mM spermidine), 5 mM Mg(OAc)2, in three steps. In the first step, we incubated wild-type (RC1) or L1(Cy5) (RC2) ribosomes with initiation factors, fMet-tRNAfMet and an mRNA containing a 3′-biotinylated DNA oligonucleotide pre-annealed to its 5′ end (see Supplementary Methods) to enzymatically form an initiation complex. We then put this initiation complex through one elongation cycle by adding EF-Tu(GTP)Phe-(Cy3)tRNAPhe and EF-G(GTP), at which point ribosomes became stalled at the stop codon residing at the third codon position within the mRNA. The efficiency of this elongation step is approximately 95%, as deduced from a standard primer extension inhibition assay8. Finally, we separated the resulting ribosomal release complexes from free mRNA, translation factors, and aatRNAs by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation in Tris-polymix buffer at 20 mM Mg(OAc)2, as previously described26.

Single-molecule experiments

We performed all experiments at room temperature in Tris-polymix buffer at 15 mM Mg(OAc)2, supplemented with an oxygen-scavenging system (300 μg ml−1 glucose oxidase, 40 μg ml−1 catalase and 1% (w/v) β-D-glucose). In addition, we added 1 mM 1,3,5,7-cyclooctatetraene (Aldrich) and p-nitrobenzyl alcohol (Fluka) to all buffers in order to quench a long-lived, non-fluorescent triplet state sampled by the Cy5 fluorophore. Previous biochemical experiments have demonstrated that the oxygen-scavenging and triplet state quencher systems have no effect on our in vitro translation system26,49.

We cleaned and subsequently derivatized quartz microscope slides with a mixture of polyethyleneglycol (PEG) and PEG-biotin in order to passivate the surface, as previously described26. Just prior to data acquisition, we treated slides with streptavidin, allowing immobilization of ribosomal release complexes bound to an mRNA with a 3′-biotinylated DNA oligonucleotide pre-annealed to its 5′ end. We collected smFRET data with a wide-field, prism-based total internal reflection fluorescence microscope utilizing a 150 mW diode-pumped 532 nm laser (CrystaLaser) operating at 24 mW for Cy3 excitation, a 25 mW diode-pumped 643 nm laser (CrystaLaser) operating at 19 mW for direct Cy5 excitation, a Dual-View multi-channel imaging system (MAG Biosystems) for separation of Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence emissions, and a back-thinned charge-coupled device camera (Cascade II, Princeton Instruments) with 2-pixel binning and 50 ms exposure time for detection. We identified single ribosomal release complexes by characteristic single-fluorophore fluorescence intensities as well as single-step fluorophore photobleaching.

Dwell-time analyses

We determined the rates of GS1→GS2 (kGS1→GS2) and GS2→GS1 (kGS2→GS1) transitions for each dataset as follows. We fit individual, fluctuating smFRETL1-tRNA trajectories to a hidden Markov model using the HaMMy software suite50 with an initial guess of 5 states. We filtered the resulting idealized trajectories such that transitions occurring with either a change in FRET of less than 0.1 or lasting only a single frame were discarded. We then extracted dwell times spent in GS1 before undergoing a transition to GS2 and dwell times spent in GS2 before undergoing a transition to GS1 from the idealized smFRET trajectories as follows. For each dataset, we plotted one-dimensional smFRET histograms from the first 0.5 seconds (i.e. 10 frames) of all traces and fit with two Gaussian distributions, centered at 0.16 for GS1 and 0.76 for GS2, using Origin 7.0. We then set thresholds corresponding to the GS1 and GS2 FRET states using the full width at half height of the Gaussian distributions. We plotted one-dimensional histograms of the time spent in GS1 and GS2 before undergoing a transition, and determined the corresponding GS1 and GS2 lifetimes by fitting each histogram to a single-exponential decay. We did not include dwell times resulting from the first and last transitions within each trajectory in this analysis due to the arbitrary onset of data collection and the stochastic nature of the photobleaching event. We subsequently increased and then decreased the thresholds by 0.03 FRET8, and repeated the analyses in order to test the sensitivity of the calculated lifetimes to the choice of thresholds. We found the sensitivity to threshold values to be minimal, and determined the average lifetime value for each dataset using the data obtained from these three sets of thresholds. Finally, we calculated kGS1→GS2 and kGS2→GS1 by taking the inverse of the GS1 and GS2 lifetimes, respectively, and applying corrections to account for premature truncation of fluctuating trajectories caused by photobleaching and the finite nature of the observation time (for more information, see Supplementary Methods).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by start-up funds to R.L.G. from Columbia University, as well as grants to R.L.G. from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (CABS 1004856), the U.S. National Science Foundation (MCB 0644262), and the American Cancer Society (RSG GMC-117152). S.H.S. was supported, in part, by the Columbia University Langmuir Scholars Program, and N.P. was supported, in part, by the Columbia University Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) Program. We are indebted to Ms. Subhasree Das for managing the Gonzalez laboratory. We thank Prof. Joachim Frank, Prof. Eric Greene, Dr. Ning Gao, and the members of the Gonzalez laboratory for valuable discussions and for carefully reading the manuscript and providing comments.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS S.H.S. and R.L.G. designed the research; S.H.S. conducted the research, except for release factor activity assays, which were conducted by S.H.S, N.P., and K.A.M., and purification of RRF, which was conducted by N.P.; J.F. provided L1(Cy5) ribosomes and offered critical discussions related to data analysis and interpretation; S.H.S. and R.L.G. wrote the manuscript; all authors approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frank J, Agrawal RK. A ratchet-like inter-subunit reorganization of the ribosome during translocation. Nature. 2000;406:318–322. doi: 10.1038/35018597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valle M, et al. Locking and unlocking of ribosomal motions. Cell. 2003;114:123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao N, et al. Mechanism for the disassembly of the posttermination complex inferred from cryo-EM studies. Mol Cell. 2005;18:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao H, et al. RF3 induces ribosomal conformational changes responsible for dissociation of class I release factors. Cell. 2007;129:929–941. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connell SR, et al. Structural basis for interaction of the ribosome with the switch regions of GTP-bound elongation factors. Mol Cell. 2007;25:751–764. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agirrezabala X, et al. Visualization of the hybrid state of tRNA binding promoted by spontaneous ratcheting of the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2008;32:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Julian P, et al. Structure of ratcheted ribosomes with tRNAs in hybrid states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16924–16927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809587105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fei J, Kosuri P, MacDougall DD, Gonzalez RL., Jr. Coupling of ribosomal L1 stalk and tRNA dynamics during translation elongation. Mol Cell. 2008;30:348–359. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ermolenko DN, et al. Observation of intersubunit movement of the ribosome in solution using FRET. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:530–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornish PV, Ermolenko DN, Noller HF, Ha T. Spontaneous intersubunit rotation in single ribosomes. Mol Cell. 2008;30:578–588. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornish PV, et al. Following movement of the L1 stalk between three functional states in single ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813180106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traut RR, Monro RE. The puromycin reaction and its relation to protein synthesis. J Mol Biol. 1964;10:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(64)80028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freistroffer DV, Pavlov MY, MacDougall J, Buckingham RH, Ehrenberg M. Release factor RF3 in E.coli accelerates the dissociation of release factors RF1 and RF2 from the ribosome in a GTP-dependent manner. EMBO J. 1997;16:4126–4133. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zavialov AV, Buckingham RH, Ehrenberg M. A posttermination ribosomal complex is the guanine nucleotide exchange factor for peptide release factor RF3. Cell. 2001;107:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirokawa G, et al. The role of ribosome recycling factor in dissociation of 70S ribosomes into subunits. RNA. 2005;11:1317–1328. doi: 10.1261/rna.2520405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zavialov AV, Hauryliuk VV, Ehrenberg M. Splitting of the posttermination ribosome into subunits by the concerted action of RRF and EF-G. Mol Cell. 2005;18:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peske F, Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W. Sequence of steps in ribosome recycling as defined by kinetic analysis. Mol Cell. 2005;18:403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawat U, et al. Interactions of the release factor RF1 with the ribosome as revealed by cryo-EM. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:1144–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klaholz BP, Myasnikov AG, Van Heel M. Visualization of release factor 3 on the ribosome during termination of protein synthesis. Nature. 2004;427:862–865. doi: 10.1038/nature02332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barat C, et al. Progression of the ribosome recycling factor through the ribosome dissociates the two ribosomal subunits. Mol Cell. 2007;27:250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson KS, Ito K, Noller HF, Nakamura Y. Functional sites of interaction between release factor RF1 and the ribosome. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:866–870. doi: 10.1038/82818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bastiaens PI, Jovin TM. Microspectroscopic imaging tracks the intracellular processing of a signal transduction protein: fluorescent-labeled protein kinase C beta I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8407–8412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hohng S, Joo C, Ha T. Single-molecule three-color FRET. Biophys J. 2004;87:1328–1337. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.043935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laurberg M, et al. Structural basis for translation termination on the 70S ribosome. Nature. 2008;454:852–857. doi: 10.1038/nature07115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zavialov AV, Mora L, Buckingham RH, Ehrenberg M. Release of peptide promoted by the GGQ motif of class 1 release factors regulates the GTPase activity of RF3. Mol Cell. 2002;10:789–798. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanchard SC, Kim HD, Gonzalez RL, Jr., Puglisi JD, Chu S. tRNA dynamics on the ribosome during translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12893–12898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403884101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HD, Puglisi JD, Chu S. Fluctuations of transfer RNAs between classical and hybrid states. Biophys J. 2007;93:3575–3582. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.109884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munro JB, Altman RB, O’Connor N, Blanchard SC. Identification of two distinct hybrid state intermediates on the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2007;25:505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartley LE, Zhuang X, Das R, Chu S, Herschlag D. Exploration of the transition state for tertiary structure formation between an RNA helix and a large structured RNA. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:1011–1026. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petry S, et al. Crystal structures of the ribosome in complex with release factors RF1 and RF2 bound to a cognate stop codon. Cell. 2005;123:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mora L, Zavialov A, Ehrenberg M, Buckingham RH. Stop codon recognition and interactions with peptide release factor RF3 of truncated and chimeric RF1 and RF2 from Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1467–1476. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karimi R, Pavlov MY, Buckingham RH, Ehrenberg M. Novel roles for classical factors at the interface between translation termination and initiation. Mol Cell. 1999;3:601–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar SK, et al. Engineered holliday junctions as single-molecule reporters for protein-DNA interactions with application to a MerR-family regulator. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12461–12467. doi: 10.1021/ja072485y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agrawal RK, et al. Visualization of ribosome-recycling factor on the Escherichia coli 70S ribosome: functional implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8900–8905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401904101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weixlbaumer A, et al. Crystal structure of the ribosome recycling factor bound to the ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:733–737. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borovinskaya MA, et al. Structural basis for aminoglycoside inhibition of bacterial ribosome recycling. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:727–732. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lancaster L, Kiel MC, Kaji A, Noller HF. Orientation of ribosome recycling factor in the ribosome from directed hydroxyl radical probing. Cell. 2002;111:129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00938-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirokawa G, et al. Binding of ribosome recycling factor to ribosomes, comparison with tRNA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35847–35852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiel MC, Raj VS, Kaji H, Kaji A. Release of ribosome-bound ribosome recycling factor by elongation factor G. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48041–48050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seo HS, et al. Kinetics and thermodynamics of RRF, EF-G, and thiostrepton interaction on the Escherichia coli ribosome. Biochemistry. 2004;43:12728–12740. doi: 10.1021/bi048927p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavlov MY, Antoun A, Lovmar M, Ehrenberg M. Complementary roles of initiation factor 1 and ribosome recycling factor in 70S ribosome splitting. EMBO J. 2008;27:1706–1717. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janosi L, et al. Evidence for in vivo ribosome recycling, the fourth step in protein biosynthesis. EMBO J. 1998;17:1141–1151. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirokawa G, Inokuchi H, Kaji H, Igarashi K, Kaji A. In vivo effect of inactivation of ribosome recycling factor - fate of ribosomes after unscheduled translation downstream of open reading frame. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:1011–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zavialov AV, Ehrenberg M. Peptidyl-tRNA regulates the GTPase activity of translation factors. Cell. 2003;114:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spahn CM, et al. Domain movements of elongation factor eEF2 and the eukaryotic 80S ribosome facilitate tRNA translocation. EMBO J. 2004;23:1008–1019. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor DJ, et al. Structures of modified eEF2 80S ribosome complexes reveal the role of GTP hydrolysis in translocation. EMBO J. 2007;26:2421–2431. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dincbas-Renqvist V, et al. A post-translational modification in the GGQ motif of RF2 from Escherichia coli stimulates termination of translation. EMBO J. 2000;19:6900–6907. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heurgue-Hamard V, Champ S, Engstrom A, Ehrenberg M, Buckingham RH. The hemK gene in Escherichia coli encodes the N(5)-glutamine methyltransferase that modifies peptide release factors. EMBO J. 2002;21:769–778. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gonzalez RL, Jr., Chu S, Puglisi JD. Thiostrepton inhibition of tRNA delivery to the ribosome. RNA. 2007;13:2091–2097. doi: 10.1261/rna.499407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKinney SA, Joo C, Ha T. Analysis of single-molecule FRET trajectories using hidden Markov modeling. Biophys J. 2006;91:1941–1951. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.