Abstract

The dual hypocretin receptor (HcrtR) antagonist almorexant (ALM) may promote sleep through selective disfacilitation of wake-promoting systems, whereas benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs) such as zolpidem (ZOL) induce sleep through general inhibition of neural activity. Previous studies have indicated that HcrtR antagonists cause less-functional impairment than BzRAs. To gain insight into the mechanisms underlying these differential profiles, we compared the effects of ALM and ZOL on functional activation of wake-promoting systems at doses equipotent for sleep induction. Sprague-Dawley rats, implanted for EEG/EMG recording, were orally administered vehicle (VEH), 100 mg/kg ALM, or 100 mg/kg ZOL during their active phase and either left undisturbed or kept awake for 90 min after which their brains were collected. ZOL-treated rats required more stimulation to maintain wakefulness than VEH- or ALM-treated rats. We measured Fos co-expression with markers for wake-promoting cell groups in the lateral hypothalamus (Hcrt), tuberomammillary nuclei (histamine; HA), basal forebrain (acetylcholine; ACh), dorsal raphe (serotonin; 5HT), and singly labeled Fos+ cells in the locus coeruleus (LC). Following SD, Fos co-expression in Hcrt, HA, and ACh neurons (but not in 5HT neurons) was consistently elevated in VEH- and ALM-treated rats, whereas Fos expression in these neuronal groups was unaffected by SD in ZOL-treated rats. Surprisingly, Fos expression in the LC was elevated in ZOL- but not in VEH- or ALM-treated SD animals. These results indicate that Hcrt signaling is unnecessary for the activation of Hcrt, HA, or ACh wake-active neurons, which may underlie the milder cognitive impairment produced by HcrtR antagonists compared to ZOL.

Introduction

Hypocretin (Hcrt, also known as orexin) neurons located in the tuberal hypothalamus (de Lecea et al, 1998; Sakurai et al, 1998) are wake-promoting neurons that project widely throughout the brain to subcortical wake-promoting regions including the tuberomammillary nuclei (TMN), basal forebrain (BF), dorsal raphe (DR), and locus coeruleus (LC) (Peyron et al, 1998). Hcrt neurons activate these brain regions (Carter et al, 2012; Eggermann et al, 2001; Eriksson et al, 2001; Liu et al, 2002; Schone et al, 2012) through the co-release of Hcrt, glutamate (GLU) (Schone et al, 2012), and dynorphin (Eriksson et al, 2004; Li et al, 2014; Muschamp et al, 2014). Hcrt neurons are active primarily during wakefulness (Lee et al, 2005), and extracellular Hcrt levels are highest during awakening and periods of heightened emotionality (Blouin et al, 2013), consistent with a role in the regulation of arousal. Degeneration of Hcrt neurons underlies the sleep disorder narcolepsy, underscoring the importance of this system for the regulation of sleep and wakefulness (Hara et al, 2001; Thannickal et al, 2000). Hcrt neurons receive afferents from several brain regions involved in homeostatic processes (Sakurai et al, 2005; Yoshida et al, 2006), indicating that these cells may integrate arousal with other physiological functions.

Insomnia affects between 10 and 30% of the population (Mai and Buysse, 2008; Roth, 2007) and can cause degradation in cognitive performance (Lamond et al, 2007). Benzodiazepine receptor agonist (BzRA) hypnotics such as zolpidem (ZOL) that are currently used to treat insomnia modulate the GABAA receptor and induce sleep through a general inhibition of neural activity. Although BzRAs are effective for the induction of sleep, they can have detrimental effects on cognitive performance (Huang et al, 2010; Uslaner et al, 2013; Wesensten et al, 1996), resulting in the need for hypnotics with an improved cognitive profile. Because of the involvement of the Hcrt system in sleep and arousal, Hcrt receptor (HcrtR) antagonists have been extensively investigated for the treatment of insomnia (Brisbare-Roch et al, 2007; Dugovic et al, 2009; Morairty et al, 2014; Roecker and Coleman, 2008; Uslaner et al, 2013; Winrow et al, 2011) and are thought to promote sleep through selective disfacilitation of wake-promoting systems. Because HcrtR antagonists may act via disfacilitation rather than generalized inhibition, they are predicted to cause less functional impairment than BzRAs (Morairty et al, 2014; Steiner et al, 2011), a hypothesis that has been supported by recent behavioral studies (Morairty et al, 2014; Tannenbaum et al, 2014; Uslaner et al, 2013).

Although HcrtR antagonists demonstrate a favorable neurocognitive profile compared with BzRAs, the neural mechanisms underlying the differential functional impairment of these drugs is not well understood. To gain insight into this phenomenon, we compared the effects of ALM and ZOL on the functional activation of the currently known wake-promoting systems to which Hcrt neurons project. We hypothesized that HcrtR blockade with ALM would inhibit activation of wake-promoting neurons to a lesser extent than ZOL treatment at equivalent sleep-promoting doses. As a test of this hypothesis, we compared Fos expression in five wake-promoting neuronal groups in the presence of these two drugs both in undisturbed conditions and during prolonged wakefulness.

Materials and methods

Animals

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by SRI International's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with National Institute of Health (NIH) guidelines. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=46; Harlan Laboratories) were housed under constant temperature (22±2 °C, 50±25% relative humidity) on a 12 h light–dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. Rats were distributed among the six experimental groups described below. EEG/EMG recordings from eight rats were not included in the final sleep data owing to poor signal quality but were included in the Fos analysis.

Surgical Procedures

To monitor EEG/EMG activity, rats were implanted with sterile telemetry transmitters (F40-EET; Data Sciences, St Paul, MN) as described previously (Morairty et al, 2008) and detailed in Supplementary Materials.

Drugs

Almorexant (ALM; (2R)-2-[(1S)-6,7-Dimethoxy-1-[2-(4-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-ethyl]-3,4-dihydro-1H-isoquinolin-2-yl]-N-methyl-2-phenyl-acetamide) was synthesized at SRI International (Menlo Park, CA) according to the literature (Koberstein et al, 2003). ZOL was supplied by Actelion Pharmaceuticals (South San Francisco, CA) or purchased from IS Chemical Company (Shanghai, China).

Experimental Protocol

Rats were orally dosed with vehicle (VEH) (1.25% hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose, 0.1% dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate, and 0.25% methylcellulose in water), ALM (100 mg/kg), or ZOL (100 mg/kg) at zeitgeber time 18 h (ZT18, Figure 1a), where ZT0=lights on and ZT12=lights off. Doses were chosen on the basis of their similar sleep-promoting efficacy, taking into account that ZOL is approximately threefold more potent when administered intraperitoneally compared with oral administration (Vanover et al, 1999), whereas ALM is equipotent through both routes of administration (Morairty et al, 2014). Following dosing, rats were either left undisturbed or kept awake (ie, sleep deprived; SD) for 90 min, after which rats were euthanized, perfused, and their brains collected for analysis. Thus, there were a total of six experimental groups: three drug treatments (VEH, ALM, and ZOL) under both undisturbed and SD conditions.

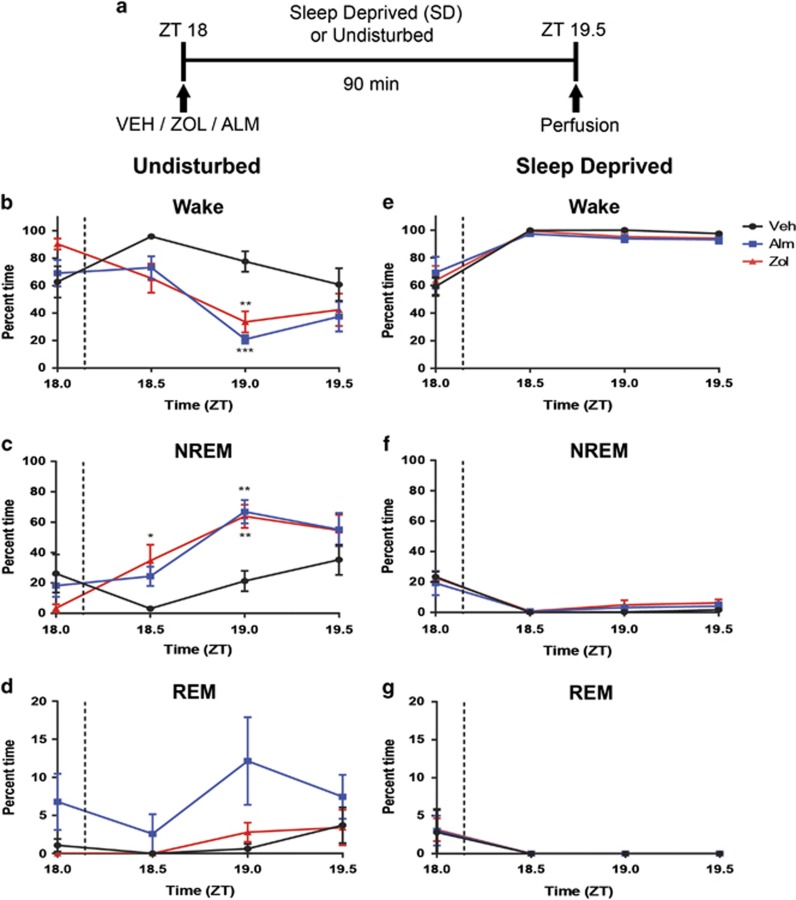

Figure 1.

Experimental paradigm and sleep/wake data. (a) At ZT18, rats were administered VEH, ALM, or ZOL and either sleep deprived or left undisturbed for 90 min. (b–d) Time spent (b) awake, (c) in NREM sleep, and (d) REM sleep following dosing in undisturbed rats. Time periods represent 30 min bins ending at the indicated time; the dashed lines show the approximate dosing time. Time spent (e) awake, (f) in NREM sleep, and (g) REM sleep in rats kept awake following dosing. N=5–7 animals/group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 compared with VEH treatment.

Sleep Deprivation Procedures

Subsets of rats were kept awake from ZT18–19.5 using procedures similar to those previously published (Dittrich et al, 2015; Morairty et al, 2014). Rats were continuously observed under dim red light during concurrent EEG/EMG recording and their cages were tapped when they were inactive and appeared to be entering a sleep state. As rats became more difficult to keep awake, progressively stronger stimulations were employed such as more forceful cage tapping, introducing novel objects into the cage, and stroking fur or vibrissae with an artist's brush.

Identification of Sleep/Wake States

At least 3 weeks post surgery, EEG and EMG were recorded as previously described (Morairty et al, 2014) using DQ ART 4.1 software (Data Sciences). After completion of data collection, expert scorers blinded to drug treatment and sleep/wake conditions determined states of sleep and wakefulness in 10 s epochs using Neuroscore software (Data Sciences). Epochs were assigned to waking (W), rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, or non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep on the basis of EEG and EMG as described previously (Dittrich et al, 2015; Morairty et al, 2014). NREM latency was defined as the time to the first three consecutive 10 s epochs of NREM sleep.

Perfusion, Fixation, and Brain Sectioning

Rats were deeply anesthetized with an overdose of euthanasia solution (150 mg/kg SomnaSol, Butler-Schein, Dublin, OH) and transcardially perfused with heparinized phosphate-buffered saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. Brains were incubated overnight in PFA before immersion in 30% sucrose. Sections were cut at 40 μm and stored in a cryoprotectant solution at −20 °C.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were first incubated with rabbit anti-Fos antibody and developed to create a black nuclear reaction product. The same sections were then incubated with either goat anti-choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) to detect cholinergic (ACh) neurons, goat anti-orexin-B for Hcrt neurons, rabbit anti-adenosine deaminase for histaminergic (HA) neurons, or rabbit anti-serotonin (5HT) for serotonergic neurons, and then developed to form a brown (ChAT, ADA, 5HT) or purple-red (Hcrt) cytoplasmic reaction product. Detailed immunohistochemistry procedures and antibody information are described in Supplementary Materials.

Cell Counts

An experimenter blinded to the drug treatments and sleep/wake conditions counted single- and double-immunoreactive cells on a Leica DM 5000B microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) with a Microfire S99808 camera (Optronics, Goleta, CA) using StereoInvestigator software (MBF Biosciences, Williston, VT). Counting areas in each brain region were defined in a manner similar to those previously described (Deurveilher et al, 2006, 2013) with minor modifications as outlined in Supplementary Materials. A rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2005) was used to define all brain regions.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA). Differences in the proportion of time spent in Wake, NREM, and REM were analyzed in 30 min time bins by two-way ANOVA on factors ‘drug treatment' (between subjects) and ‘time' (within subjects) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test where appropriate. Sleep latency was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Differences in Fos co-labeling were analyzed by two-way ANOVA on factors ‘drug treatment' (between subjects) and ‘sleep/wake condition' (SD or undisturbed, between subjects) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test if two-way ANOVA indicated an interaction between the factors. Statistical significance was established as p<0.05.

Results

Pharmacologically-Induced Sleep

The doses of ALM and ZOL used in the present study (100 mg/kg, p.o) were chosen because they have roughly equivalent sleep induction efficacy in rats and, for ALM, result in high occupancy of both Hcrt receptors (Morairty et al, 2012). Both ALM and ZOL significantly decreased the latency to first NREM sleep bout relative to VEH (18.6±2.6 min for ALM, 16.1±3.9 min for ZOL vs 36.7±7.6 min for VEH; p<0.05 for both comparisons with VEH) in rats left undisturbed after dosing. Significant interactions between time and drug treatment were found in undisturbed animals for wake (F(6,42)=4.34; p=0.002) and NREM (F(6,42)=3.86; p=0.004) time during the 90 min period post dosing. Both ALM- and ZOL-treated rats exhibited less time awake and more time in NREM than VEH-treated rats; no differences were found between ALM- and ZOL-treated rats (Figure 1b and c). For REM sleep, a main effect was found for drug treatment (F(2,14)=6.074; p=0.01) that was largely due to ALM treatment (Figure 1d).

SD was highly effective for all groups, as rats were awake >95% of the time during SD regardless of drug treatment (Figure 1e). No significant differences were found in wake, NREM (Figure 1f), or REM (Figure 1g) time during SD for either ALM or ZOL compared with VEH. However, frequent and vigorous manipulations during SD were required to maintain wakefulness in ZOL-treated rats, whereas ALM-treated rats required only mild interventions to maintain wakefulness.

Fos Immunoreactivity in Hypocretin Neurons

Figure 2a–d and Supplementary Figure S1 present representative sections from the LH in which the sections were stained for both Fos and Hcrt. Across the entire Hcrt field, there was an interaction between drug treatment and sleep/wake condition (F(2,40)=4.945; p=0.012). Fos expression in Hcrt neurons was elevated during SD compared with undisturbed controls under both VEH (p=0.007) and ALM (p<0.0001) but not ZOL treatment. Furthermore, ALM-treated SD rats co-expressed significantly greater levels of Fos than did ZOL-treated SD rats (p=0.002; Figure 2e), with VEH-treated rats trending similarly.

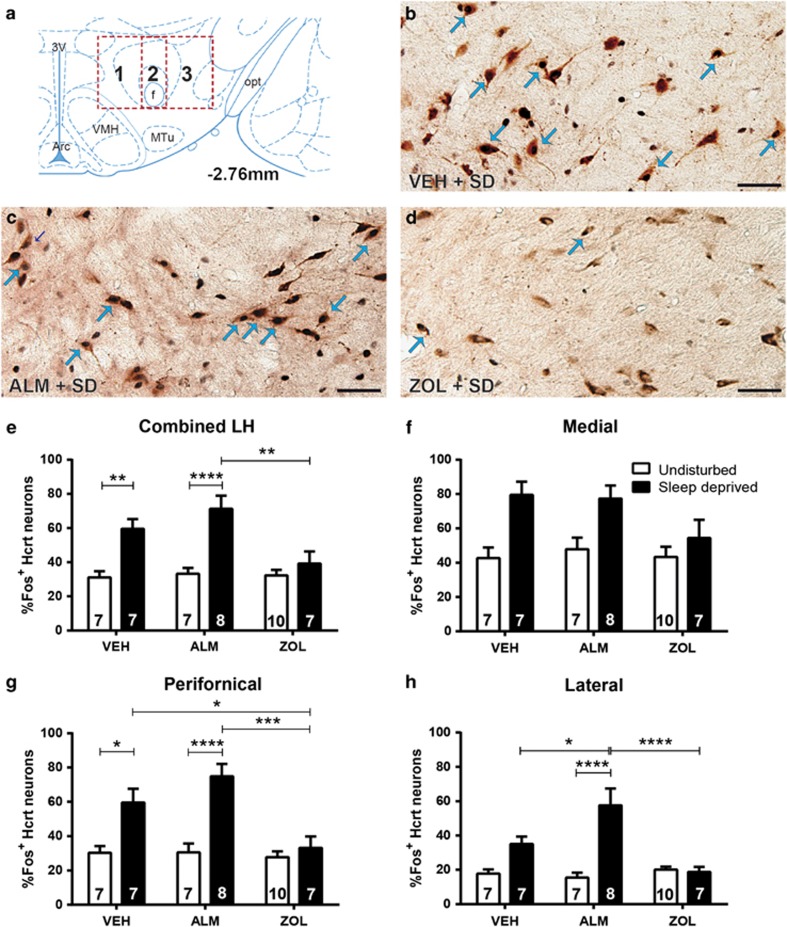

Figure 2.

Fos labeling of Hcrt neurons in the LH. (a) Boxes delineate the regions scored within the Hcrt field; 1, 2, and 3 in the boxes, respectively, correspond to the medial, perifornical, and lateral hypothalamic regions. (b–d) Fos-positive nuclei are small black dots and Hcrt neurons have reddish-brown cytoplasmic reaction products. Blue arrows indicate representative co-labeled neurons. Scale bar=50 μM. Representative image of Hcrt and Fos expression in a sleep-deprived rat treated with (b) VEH, (c) ALM, or (d) ZOL. (e) Combined analysis of all Hcrt neurons examined throughout the Hcrt field, (f) in the medial field, (g) perifornical area, and (h) lateral portions of the LH. Numbers in bars indicate N per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001 compared with the indicated treatment group.

Given the differences in Fos expression in the entire Hcrt neuron population, we sought to determine whether regional heterogeneity occurred and counted Hcrt cells within the medial, perifornical, and lateral hypothalamus as described above. In the medial portion of the Hcrt field (Figure 2f), a main effect for sleep/wake condition (F(1,40)=17.76; p<0.0001) but not drug treatment was found.

In the perifornical area (Figure 2g), there was a significant interaction between drug treatment and sleep/wake condition (F(2,40)=6.137; p=0.0047). SD significantly elevated Fos expression in Hcrt neurons under VEH (p=0.014) and ALM (p=0.0001) but not ZOL treatments. Similarly, both VEH- (p=0.035) and ALM-treated (p=0.0002) SD rats exhibited significantly greater levels of Fos co-expression than did ZOL-treated SD rats.

In the LH (Figure 2h), we identified a significant interaction between drug treatment and sleep/wake condition (F(2,40)=12.11; p<0.0001). Fos co-expression was elevated by SD relative to undisturbed conditions only in ALM-treated rats (p<0.0001); VEH-treated rats exhibited a similar trend. ALM treatment resulted in greater Fos expression compared with both VEH- (p=0.02) and ZOL-treated (p<0.0001) SD animals.

These results indicate that VEH and ALM are permissive for forced wakefulness-induced activation of Hcrt neurons, whereas this phenomenon is suppressed by ZOL. These effects were most robust in the perifornical area and attenuated in the medial Hcrt field.

Fos Immunoreactivity in HA Neurons

Figure 3a–d and Supplementary Figure S2 present representative sections from the TMN that were stained for Fos and ADA. A significant interaction between drug treatment and sleep/wake condition (F(2,40)=3.57; p<0.038) was found in a combined analysis of the HA field. Fos expression in HA neurons was increased during SD relative to undisturbed conditions for both VEH- (p=0.02) and ALM- (p<0.0004) but not ZOL-treated rats (Figure 3e). Both VEH- (p=0.0004) and ALM-treated (p=0.0011) SD rats exhibited significantly elevated Fos co-expression compared with ZOL-treated SD animals.

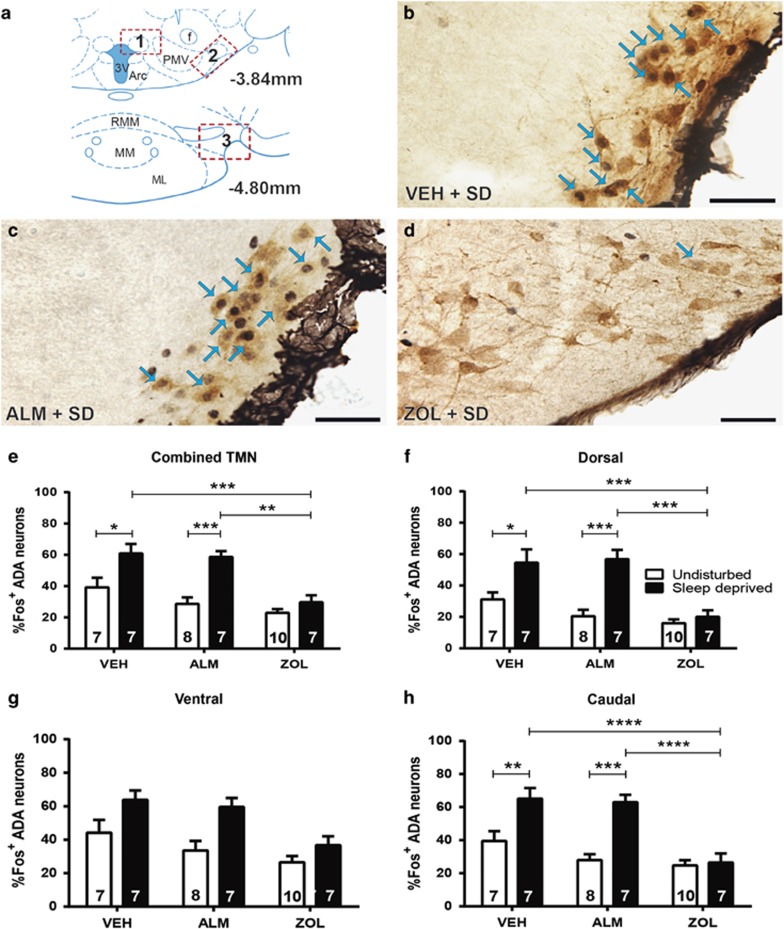

Figure 3.

Fos labeling of HA neurons in the TMN. (a) Boxes delineate the TMN regions scored; 1, 2, and 3 correspond to the dTMN, vTMN, and cTMN, respectively. (b–d) Fos-positive nuclei are small black dots and HA-expressing neurons have brown cytoplasmic reaction products. Blue arrows indicate examples of co-labeled neurons. Scale bar represents 50 μM. Representative image of HA neurons and Fos in a sleep-deprived rat treated with (b) VEH, (c) ALM, or (d) ZOL. (e) Combined analysis of all scored HA neurons throughout the HA field, (f) in the dTMN, (g) vTMN, and (h) cTMN. Numbers in bars indicate N per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001 compared with the indicated treatment group.

On the basis of the overall differences in Fos expression in HA neurons, we examined the three major subregions of the TMN: the dTMN, vTMN, and cTMN. For the dTMN, there was a significant interaction between drug treatment and sleep/wake condition (F(2,40)=5.53; p=0.008). VEH- (p=0.03) and ALM- (p<0.0001) but not ZOL-treated rats exhibited enhanced Fos co-expression during SD compared with undisturbed conditions. Similarly, Fos expression was significantly higher in SD rats treated with VEH (p=0.0004) or ALM (p=0.0002) compared with ZOL (Figure 3f).

Less-pronounced effects were observed in the vTMN (Figure 3g), as main effects for drug treatment (F(2,40)=8.74; p=0.0007) and sleep/wake condition (F(1,40)=17.16; p=0.0002) were found, but there was no significant interaction between the factors.

Clear differences were observed for the cTMN (Figure 3h), as a significant interaction was found between drug treatment and sleep/wake condition (F(2,40)=6.66; p=0.003). VEH- (p=0.001) and ALM- (p<0.0001) but not ZOL-treated rats exhibited increased Fos levels during SD compared with undisturbed conditions; both VEH- (p<0.0001) and ALM-treated (p<0.0001) SD rats exhibited greater Fos co-expression than ZOL-treated SD rats.

These results indicate that, as in Hcrt neurons, VEH and ALM permit SD-induced activation of HA neurons, whereas this effect was suppressed by ZOL. This phenomenon was attenuated in the vTMN.

Fos Immunoreactivity in Cholinergic Neurons

Representative sections from ACh neurons in the BF are shown in Figure 4a–d and Supplementary Figure S3. Consistent with previous reports on the effects of forced wakefulness in the BF (McKenna et al, 2009), relatively modest absolute levels of Fos/ChAT co-expression were found compared with levels in the LH and TMN. However, drug treatment and sleep/wake condition had significant effects on Fos co-expression across the BF, as a significant interaction (F(2,40)=6.747; p=0.003) between these factors was found. SD increased Fos co-expression compared with undisturbed conditions for both VEH (p=0.044) and ALM (p=0.0012) but not ZOL-treated animals. Both VEH (p=0.0024) and ALM (p<0.0001) led to significantly higher Fos co-expression compared with ZOL treatment in SD animals (Figure 4e).

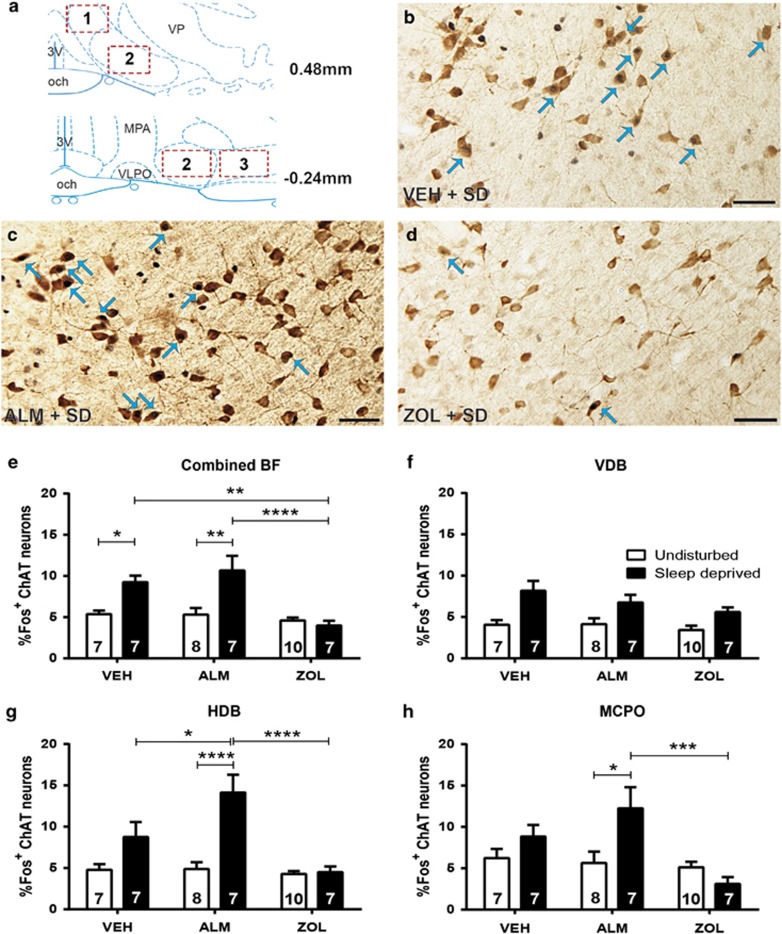

Figure 4.

Fos co-labeling with ACh neurons in the BF. (a) Boxes delineate the BF regions that were scored; 1, 2, and 3 correspond to the VDB, HDB, and MCPO, respectively. The HDB was counted at multiple rostral-caudal levels. (b–d): Fos-positive nuclei are small black dots and ACh-expressing neurons have brown cytoplasmic reaction products. Blue arrows indicate examples of co-labeled neurons. Scale bar represents 50 μM. Representative image of HA and Fos expression in sleep-deprived rat treated with (b) VEH, (c) ALM, or (d) ZOL. (e) Combined analysis of all ACh neurons examined for co-labeling throughout the ACh field, (f) in the VDB, (g) HDB, and (h) MCPO. Numbers in bars indicate N per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001 compared with the indicated treatment group.

We next investigated Fos co-expression in subregions of the BF to understand the regional specificity of this effect. In the VDB (Figure 4f), sleep/wake condition was the only factor to exhibit a main effect (F(1,40)=22.19; p=0.0001), indicating that the overall effect is less prominent in this subregion.

The effects of drug treatment and sleep/wake condition were more profound in the HDB where a clear interaction between the two factors (F(2,40)=7.566; p=0.002) was found. SD significantly elevated Fos/ChAT co-expression compared with undisturbed condition for ALM-treated rats (p<0.0001). ALM-treated SD rats exhibited greater Fos co-expression than both VEH- (p=0.04) and ZOL-treated (p<0.0001) SD rats (Figure 4g).

A significant interaction between drug treatment and sleep/wake condition (F(2,40)=5.03; p=0.01) occurred in the MCPO (Figure 4e). SD increased Fos expression compared to undisturbed conditions in ALM-treated rats (p=0.02), which exhibited significantly greater Fos expression than ZOL-treated SD rats (p=0.0008).

Taken together, these results indicate that ALM is permissive for forced wakefulness-induced activation of BF cholinergic neurons, whereas ZOL inhibits their activation. This effect was evident in the HDB and, to a lesser extent, the MCPO.

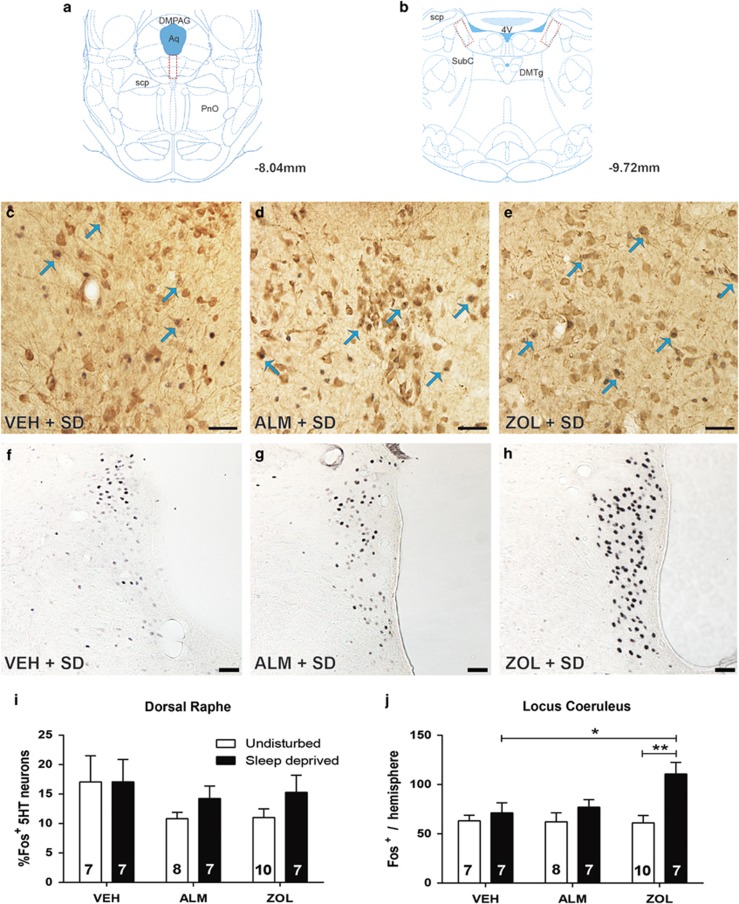

Fos Immunoreactivity in Serotonergic Neurons

5HT-expressing neurons were analyzed for Fos co-labeling following VEH, ALM, or ZOL treatment under SD and undisturbed conditions (Figure 5a, c–e and i and Supplementary Figure S4A–C). No significant effects of drug treatment or sleep/wake condition on Fos co-expression were found.

Figure 5.

Fos co-labeling with 5HT neurons in the DR and single-labeled Fos cells in the LC. (a–b) Boxes delineate the regions scored in the (a) DR and (b) LC. In (c–h) Fos-positive nuclei are small black dots and 5HT-expressing neurons have brown cytoplasmic reaction products. Blue arrows indicate examples of co-labeled neurons. Scale bar represents 50 μM. Representative image of 5HT and Fos expression in a sleep-deprived rat treated with (c) VEH, (d) ALM, or (e) ZOL. (f) Fos expression in the LC of a sleep-deprived rat treated with VEH, (g) ALM, or (h) ZOL. (i) Combined analysis of all scored 5HT neurons in the DR. (j) Analysis of Fos labeling in the LC for each treatment condition. Numbers in bars indicate N per group. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared with the indicated treatment group.

Fos Immunoreactivity in LC Neurons

Analysis of single-labeled Fos expression in the LC (Figure 5b, f–h and j, and Supplementary Figure S4D–F) identified a significant interaction between sleep/wake condition and drug treatment (F(2,40)=3.27; p=0.049). In contrast to other brain regions, SD increased Fos expression in ZOL-treated (p=0.0022) but not in VEH- or ALM-treated rats.

Discussion

These results establish that ALM is permissive for the activation of Hcrt neurons in the LH, HA neurons in the TMN, and ACh neurons in the BF during periods of forced vigilance, whereas an equipotent dose of ZOL inhibits activation of these cell groups. These observations are consistent with different downstream sleep-promoting mechanisms for the two drugs, with ZOL promoting sleep through pan-neuronal inhibition and ALM through disfacilitation mediated by HcrtR blockade. We conclude that ALM does not inhibit the recruitment of wake-promoting Hcrt, HA, or ACh neurons during periods of increased vigilance. These results also indicate that HcrtRs are not essential for short-term activation of Hcrt, HA, or ACh neuronal populations. Surprisingly, our results also demonstrate that ZOL-treated animals exhibit elevated Fos expression in the LC following SD.

All-known wake-promoting cell groups express HcrtRs and are innervated by Hcrt neurons (Bayer et al, 2001; Eggermann et al, 2001; Eriksson et al, 2001; Li et al, 2002; Marcus et al, 2001; Peyron et al, 1998; Yamanaka et al, 2002). If ALM were to promote sleep through inhibition of downstream targets, it would be expected to interfere with the activation of wake-promoting cell groups. The fact that three major wake-active cell groups in the LH, TMN, and BF all demonstrated elevated Fos expression during periods of forced vigilance in the presence of ALM indicates that ALM and, by extension, at least partial HcrtR blockade is permissive for the functional activation of these groups. As many of these groups exhibit subregion-specific connectivity patterns (Ericson et al, 1987; Harris and Aston-Jones, 2006; Jones, 2003; Lee et al, 2008; Yoshida et al, 2006), we examined Fos expression in the major subregions of the LH, TMN, and BF. We found some degree of variation in Fos expression patterns between the subregions, suggesting this may influence response to HcrtR antagonists. Hcrt neurons in the perifornical area regulate stress and arousal responses (Harris and Aston-Jones, 2006), which may partially explain their greater sensitivity to SD in VEH-treated rats compared with the lateral Hcrt field. Variation in Fos co-expression patterns were found between the BF subregions, but similar patterns were found between the HDB and MCPO, which exhibit differential projection patterns (Jones, 2003), suggesting that most outputs of the BF may be affected similarly by ALM. The projections of HA subregions are not topographically organized (Schwartz et al, 1991), so the significance of their subregional heterogeneity is unclear.

Our results from the DR and LC are inconclusive in that forced vigilance did not elevate Fos expression under most conditions nor was there any indication that ALM or ZOL inhibited their activity, ie, reduced Fos expression relative to VEH. Although it was unexpected that the LC and DR did not increase Fos expression in response to SD in VEH-treated animals, the mixed downstream effects of NE and generally inhibitory effects of 5HT on other wake-promoting cell groups (Brown et al, 2012; Li et al, 2002; Li and van den Pol, 2005) contrast with the excitatory effects of Hcrt, HA, and ACh on these groups (Saper et al, 2001), suggesting that the LC and DR may be differentially regulated. The elevated Fos expression observed in the LC following forced wakefulness in ZOL but not VEH or ALM treatment groups is also surprising considering the inhibitory effect of ZOL in other regions, but this may be a result of the greatly increased level of stimulation required to keep ZOL-treated rats awake during forced wakefulness coupled with the high sensitivity of Fos expression in the LC to stress (Sved et al, 2002). However, it is also possible that ZOL facilitates activation of the LC.

These results indicate that ALM disfacilitates Hcrt-induced excitation of wake-promoting regions, but does not block activation of these cell groups by other neurotransmitters during periods of forced vigilance. Hcrt neurons also co-release GLU (Henny et al, 2010; Schone et al, 2012); thus, Hcrt neurons may release GLU in terminal fields within the LH, TMN, and BF in response to stressors requiring increased vigilance in the presence of ALM. GLU release from Hcrt neurons is sufficient to enhance firing of HA neurons in the TMN in vitro (Schone et al, 2012), suggesting that Hcrt neurons can engage fast glutamatergic regulation of downstream targets in the absence of HcrtR activation. However, it is also possible that increased Fos co-labeling is independent of Hcrt neuronal activity and is driven by other arousal systems. This combination of glutamatergic input from Hcrt neurons and excitatory transmission originating from other wake-promoting regions may explain why Hcrt, HA, and ACh neurons can be activated in the presence of ALM.

Another clue as to the mechanisms underlying how Hcrt antagonists promote sleep comes from our recent study, demonstrating that ALM increases adenosine (ADO) levels in both the BF and cortex (Vazquez-DeRose et al, 2014), and that some of its sleep-promoting effects are dependent on the intact functionality of BF cholinergic neurons. Interestingly, microinjection of ALM directly into the BF both promoted sleep and increased ADO concentrations in the cortex, further supporting a role for the BF as a component of the circuitry underlying ALM's sleep-promoting effects. Microinjection of ALM into other wake-promoting regions was not performed in this study, so their relative contribution to ALM's effects are unknown. However, these results are consistent with those of the current study and suggest that ALM may function both by promoting the release of a sleep-promoting neurotransmitter and by disfacilitating the wake-promoting effects of Hcrt.

Limitations in the study design should be considered when interpreting the current results. First, the rats were dosed at ZT18, a time with low natural sleep pressure when wake-promoting systems are highly active. It is possible that different results would be obtained if rats were dosed during the light phase when homeostatic and circadian influences may contribute to a higher activation threshold for these neuronal groups. Second, the SD protocol used in this study lasted only 90 min and thus was unlikely to markedly increase sleep pressure, suggesting that novelty and handling stress also contributed to the elevated Fos co-expression observed in most wake-active regions. The intensity of SD required to maintain wakefulness was not quantified, making it difficult to determine the degree to which differences in handling stress between the treatment groups may have influenced results. Third, although our results indicate that neither ALM nor ZOL inhibit Fos co-expression in wake-promoting neurons of undisturbed animals, the poor temporal resolution of Fos must be considered as it is possible that 90 min post dosing may not allow sufficient time for baseline Fos level to be fully degraded, which could mask inhibitory drug effects.

Interestingly, we found that ALM-treated SD rats exhibited significantly greater Fos co-expression than did VEH-treated rats in the lateral Hcrt field and the HDB. The underlying cause of this is unclear, as our central hypothesis suggests that two groups should exhibit similar levels of Fos co-expression. One possible explanation is that these regions may be particularly stress-sensitive and the stimulation required to keep ALM-treated rats awake during SD provoked a stress response, resulting in greater Fos activation. However, although LH Hcrt neurons are known to be stress-sensitive (Espana et al, 2003), evidence for HDB stress-responsiveness is limited. Another possibility is that ALM may facilitate greater Fos co-expression in these regions through the mechanisms that are not yet understood.

ZOL and similar drugs like eszopiclone are widely prescribed and generally considered effective at inducing sleep (Greenblatt and Roth, 2012), but their use is associated with a high incidence of adverse effects such as driving impairment (Gunja, 2013; Verster et al, 2006), memory impairment (Balkin et al, 1992; Mintzer and Griffiths, 1999; Wesensten et al, 1995, 1996), complex sleep behaviors (Chen et al, 2014; Dolder and Nelson, 2008), and psychomotor deficits (Storm et al, 2007; Wesensten et al, 2005), highlighting the need for hypnotics that induce less-functional impairment. ALM and other HcrtR antagonists effectively induce sleep (Brisbare-Roch et al, 2007; Cox et al, 2010) but cause less impairment in memory tasks (Dietrich and Jenck, 2010; Morairty et al, 2014) or motor function in rodents (Ramirez et al, 2013; Steiner et al, 2011), dogs (Tannenbaum et al, 2014), and non-human primates (Uslaner et al, 2013) than do traditional hypnotics. Although some degree of impairment may occur at high doses in humans (Hoever et al, 2010; Jacobson et al, 2014), HcrtR antagonists are expected to exhibit a favorable safety profile compared with ZOL and other hypnotics, though years of post-market surveillance will be needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Our finding that the functional activation of Hcrt, HA, and ACh wake-promoting neurons is unaffected by ALM but inhibited by ZOL provides a possible explanation for reports describing a reduced impairment profile for Hcrt antagonists compared with ZOL. The ability of these neurons to be recruited in response to stimuli requiring alertness in the presence of ALM indicates that these arousal systems can function normally in the presence of the drug. The current results strongly suggest that ALM causes less functional impairment than ZOL at least in part because it does not impair activation of wake-promoting systems in response to salient stimuli.

Funding and disclosure

The authors declare no financial conflict of interests regarding the subject of this work. Over the past 3 years, GSP has received research support from Genentech. SRM has received research support from F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and CHDI. TCN has consulted for Genentech and received study medication from Actelion for a study funded by the Department of Defense, and study medication from Glaxo-Smith Kline for a study funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. TSK has served as a consultant for NIH, the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science, Merck Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer; made paid educational presentations for the benefit of APSS, LLC, the Physician's Postgraduate Press, and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; and received research support from F Hoffmann-LaRoche, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, CHDI, and Inscopix.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by USAMRAA Grant DR080789P1, DFG fellowship DI 1718/1-1, and NIH R01 NS077408. We thank Alan Wilk, Michael Miller, and Webster Lincoln for assistance with the experiments and Rhiannan Williams for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Balkin TJ, O'Donnell VM, Wesensten N, McCann U, Belenky G (1992). Comparison of the daytime sleep and performance effects of zolpidem versus triazolam. Psychopharmacology 107: 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer L, Eggermann E, Serafin M, Saint-Mleux B, Machard D, Jones B et al (2001). Orexins (hypocretins) directly excite tuberomammillary neurons. Eur J Neurosci 14: 1571–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin AM, Fried I, Wilson CL, Staba RJ, Behnke EJ, Lam HA et al (2013). Human hypocretin and melanin-concentrating hormone levels are linked to emotion and social interaction. Nat Commun 4: 1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisbare-Roch C, Dingemanse J, Koberstein R, Hoever P, Aissaoui H, Flores S et al (2007). Promotion of sleep by targeting the orexin system in rats, dogs and humans. Nat Med 13: 150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Basheer R, McKenna JT, Strecker RE, McCarley RW (2012). Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol Rev 92: 1087–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter ME, Brill J, Bonnavion P, Huguenard JR, Huerta R, de Lecea L (2012). Mechanism for Hypocretin-mediated sleep-to-wake transitions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: e2635–e2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CS, Huang MF, Hwang TJ, Chen ST, Ko CH, Yen CN et al (2014). Clinical correlates of zolpidem-associated complex sleep-related behaviors: age effect. J Clin Psychiatry 75: e1314–e1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CD, Breslin MJ, Whitman DB, Schreier JD, McGaughey GB, Bogusky MJ et al (2010). Discovery of the dual orexin receptor antagonist [(7 R)-4-(5-chloro-1,3-benzoxazol-2-yl)-7-methyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl][5-methy l-2-(2H-1,2,3-triazol-2-yl)phenyl]methanone (MK-4305) for the treatment of insomnia. J Med Chem 53: 5320–5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X-B, Foye PE, Danielson PE et al (1998). The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 322–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deurveilher S, Lo H, Murphy JA, Burns J, Semba K (2006). Differential c-Fos immunoreactivity in arousal-promoting cell groups following systemic administration of caffeine in rats. J Comp Neurol 498: 667–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deurveilher S, Ryan N, Burns J, Semba K (2013). Social and environmental contexts modulate sleep deprivation-induced c-Fos activation in rats. Behav Brain Res 256: 238–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich H, Jenck F (2010). Intact learning and memory in rats following treatment with the dual orexin receptor antagonist almorexant. Psychopharmacology 212: 145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich L, Morairty SR, Warrier DR, Kilduff TS (2015). Homeostatic sleep pressure is the primary factor for activation of cortical nNOS/NK1 neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology 40: 632–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolder CR, Nelson MH (2008). Hypnosedative-induced complex behaviours: incidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs 22: 1021–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugovic C, Shelton JE, Aluisio LE, Fraser IC, Jiang X, Sutton SW et al (2009). Blockade of orexin-1 receptors attenuates orexin-2 receptor antagonism-induced sleep promotion in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 330: 142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermann E, Serafin M, Bayer L, Machard D, Saint-Mleux B, Jones BE et al (2001). Orexins/hypocretins excite basal forebrain cholinergic neurones. Neuroscience 108: 177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson H, Watanabe T, Kohler C (1987). Morphological analysis of the tuberomammillary nucleus in the rat brain: delineation of subgroups with antibody against L-histidine decarboxylase as a marker. J Comp Neurol 263: 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson KS, Sergeeva O, Brown RS, Haas HL (2001). Orexin/hypocretin excites the histaminergic neurons of the tuberomammillary nucleus. J Neurosci 21: 9273–9279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson KS, Sergeeva OA, Selbach O, Haas HL (2004). Orexin (hypocretin)/dynorphin neurons control GABAergic inputs to tuberomammillary neurons. Eur J Neurosci 19: 1278–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espana RA, Valentino RJ, Berridge CW (2003). Fos immunoreactivity in hypocretin-synthesizing and hypocretin-1 receptor-expressing neurons: effects of diurnal and nocturnal spontaneous waking, stress and hypocretin-1 administration. Neuroscience 121: 201–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt DJ, Roth T (2012). Zolpidem for insomnia. Expert Opin Pharmacother 13: 879–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunja N (2013). In the Zzz zone: the effects of Z-drugs on human performance and driving. J Med Toxicol 9: 163–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM et al (2001). Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron 30: 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Aston-Jones G (2006). Arousal and reward: a dichotomy in orexin function. Trends Neurosci 29: 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henny P, Brischoux F, Mainville L, Stroh T, Jones BE (2010). Immunohistochemical evidence for synaptic release of glutamate from orexin terminals in the locus coeruleus. Neuroscience 169: 1150–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoever P, de Haas S, Winkler J, Schoemaker RC, Chiossi E, van Gerven J et al (2010). Orexin receptor antagonism, a new sleep-promoting paradigm: an ascending single-dose study with almorexant. Clin Pharmacol Ther 87: 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoever P, de Haas SL, Dorffner G, Chiossi E, van Gerven JM, Dingemanse J (2012). Orexin receptor antagonism: an ascending multiple-dose study with almorexant. J Psychopharmacol 26: 1071–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang MP, Radadia K, Macone BW, Auerbach SH, Datta S (2010). Effects of eszopiclone and zolpidem on sleep-wake behavior, anxiety-like behavior and contextual memory in rats. Behav Brain Res 210: 54–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson LH, Callander GE, Hoyer D (2014). Suvorexant for the treatment of insomnia. Expert Rev Clin P 7: 711–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE (2003). Arousal systems. Front Biosci 8: s438–s451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko EM, Estabrooke IV, McCarthy M, Scammell TE (2003). Wake-related activity of tuberomammillary neurons in rats. Brain Res 992: 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koberstein R, Aissaoui H, Bur D, Clozel M, Fischli W, Jenck F et al (2003). Tetrahydroisoquinolines as orexin receptor antagonists: strategies for lead optimization by solution-phase chemistry. Chimia 57: 270–275. [Google Scholar]

- Koberstein R, Fischll W, Clozel M, Aissaou H, Weller T (2005) Substituted 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives. In: WIPO (ed). WIPO. Actelion Pharm. LTD. [Google Scholar]

- Lamond N, Jay SM, Dorrian J, Ferguson SA, Jones C, Dawson D (2007). The dynamics of neurobehavioural recovery following sleep loss. J Sleep Res 16: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Hassani OK, Jones BE (2005). Discharge of identified orexin/hypocretin neurons across the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci 25: 6716–6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SB, Chang BJ, Lee HS (2008). Organization of histamine-immunoreactive, tuberomammillary neurons projecting to the dorsal tier of the substantia nigra compacta in the rat. Brain Res 1203: 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Marchant NJ, Shaham Y (2014). Opposing roles of cotransmission of dynorphin and hypocretin on reward and motivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 5765–5766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gao XB, Sakurai T, van den Pol AN (2002). Hypocretin/Orexin excites hypocretin neurons via a local glutamate neuron-A potential mechanism for orchestrating the hypothalamic arousal system. Neuron 36: 1169–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, van den Pol AN (2005). Direct and indirect inhibition by catecholamines of hypocretin/orexin neurons. J Neurosci 25: 173–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RJ, van den Pol AN, Aghajanian GK (2002). Hypocretins (orexins) regulate serotonin neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus by excitatory direct and inhibitory indirect actions. J Neurosci 22: 9453–9464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai E, Buysse DJ (2008). Insomnia: prevalence, impact, pathogenesis, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. Sleep Med Clin 3: 167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M et al (2001). Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 435: 6–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna JT, Cordeira JW, Jeffrey BA, Ward CP, Winston S, McCarley RW et al (2009). c-Fos protein expression is increased in cholinergic neurons of the rodent basal forebrain during spontaneous and induced wakefulness. Brain Res Bull 80: 382–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintzer MZ, Griffiths RR (1999). Selective effects of zolpidem on human memory functions. J Psychopharmacol 13: 18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morairty SR, Dittrich L, Pasumarthi RK, Valladao D, Heiss JE, Gerashchenko D et al (2013). A role for cortical nNOS/NK1 neurons in coupling homeostatic sleep drive to EEG slow wave activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 20272–20277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morairty SR, Hedley L, Flores J, Martin R, Kilduff TS (2008). Selective 5HT2A and 5HT6 receptor antagonists promote sleep in rats. Sleep 31: 34–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morairty SR, Revel FG, Malherbe P, Moreau JL, Valladao D, Wettstein JG et al (2012). Dual hypocretin receptor antagonism is more effective for sleep promotion than antagonism of either receptor alone. PLoS One 7: e39131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morairty SR, Wilk AJ, Lincoln WU, Neylan TC, Kilduff TS (2014). The hypocretin/orexin antagonist almorexant promotes sleep without impairment of performance in rats. Front Neurosci 8: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschamp JW, Hollander JA, Thompson JL, Voren G, Hassinger LC, Onvani S et al (2014). Hypocretin (orexin) facilitates reward by attenuating the antireward effects of its cotransmitter dynorphin in ventral tegmental area. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: e1648–e1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (2005) The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 5th edn. Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam; Boston, xliii p, 166 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG et al (1998). Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci 18: 9996–10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez AD, Gotter AL, Fox SV, Tannenbaum PL, Yao L, Tye SJ et al (2013). Dual orexin receptor antagonists show distinct effects on locomotor performance, ethanol interaction and sleep architecture relative to gamma-aminobutyric acid-A receptor modulators. Front Neurosci 7: 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roecker AJ, Coleman PJ (2008). Orexin receptor antagonists: medicinal chemistry and therapeutic potential. Curr Top Med Chem 8: 977–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T (2007). Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med 3(5 Suppl): S7–S10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H et al (1998). Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 92: 1 page following 696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Nagata R, Yamanaka A, Kawamura H, Tsujino N, Muraki Y et al (2005). Input of orexin/hypocretin neurons revealed by a genetically encoded tracer in mice. Neuron 46: 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB, Chou TC, Scammell TE (2001). The sleep switch: hypothalamic control of sleep and wakefulness. Trends Neurosci 24: 726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schone C, Apergis-Schoute J, Sakurai T, Adamantidis A, Burdakov D (2014). Coreleased orexin and glutamate evoke nonredundant spike outputs and computations in histamine neurons. Cell Rep 7: 697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schone C, Cao ZF, Apergis-Schoute J, Adamantidis A, Sakurai T, Burdakov D (2012). Optogenetic probing of fast glutamatergic transmission from hypocretin/orexin to histamine neurons in situ. J Neurosci 32: 12437–12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JC, Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Pollard H, Ruat M (1991). Histaminergic transmission in the mammalian brain. Physiol Rev 71: 1–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner MA, Lecourt H, Strasser DS, Brisbare-Roch C, Jenck F (2011). Differential effects of the dual orexin receptor antagonist almorexant and the GABA(A)-alpha1 receptor modulator zolpidem, alone or combined with ethanol, on motor performance in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology 36: 848–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm WF, Eddy DR, Welch CB, Hickey PA, Fischer J, Cardenas R (2007). Cognitive performance following premature awakening from zolpidem or melatonin induced daytime sleep. Aviation space Environ Med 78: 10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sved AF, Cano G, Passerin AM, Rabin BS (2002). The locus coeruleus, Barrington's nucleus, and neural circuits of stress. Physiol Behav 77: 737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum PL, Stevens J, Binns J, Savitz AT, Garson SL, Fox SV et al (2014). Orexin receptor antagonist-induced sleep does not impair the ability to wake in response to emotionally salient acoustic stimuli in dogs. Front Behav Neurosci 8: 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal T, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M et al (2000). Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron 27: 469–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner JM, Tye SJ, Eddins DM, Wang X, Fox SV, Savitz AT et al (2013). Orexin receptor antagonists differ from standard sleep drugs by promoting sleep at doses that do not disrupt cognition. Sci Transl Med 5: 179ra144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanover KE, Edgar DM, Seidel WF, Hogenkamp DJ, Fick DB, Lan NC et al (1999). Response-rate suppression in operant paradigm as predictor of soporific potency in rats and identification of three novel sedative-hypnotic neuroactive steroids. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291: 1317–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-DeRose J, Schwartz MD, Nguyen AT, Warrier DR, Gulati S, Mathew TK et al (2014). Hypocretin/orexin antagonism enhances sleep-related adenosine and GABA neurotransmission in rat basal forebrain. Brain Structure Funct (e-pub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Verster JC, Veldhuijzen DS, Patat A, Olivier B, Volkerts ER (2006). Hypnotics and driving safety: meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials applying the on-the-road driving test. Curr Drug Safety 1: 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesensten NJ, Balkin TJ, Belenky GL (1995). Effects of daytime administration of zolpidem versus triazolam on memory. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 48: 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesensten NJ, Balkin TJ, Belenky GL (1996). Effects of daytime administration of zolpidem and triazolam on performance. Aviation Space Environ Med 67: 115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesensten NJ, Balkin TJ, Reichardt RM, Kautz MA, Saviolakis GA, Belenky G (2005). Daytime sleep and performance following a zolpidem and melatonin cocktail. Sleep 28: 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winrow CJ, Gotter AL, Cox CD, Doran SM, Tannenbaum PL, Breslin MJ et al (2011). Promotion of sleep by suvorexant-a novel dual orexin receptor antagonist. J Neurogenet 25: 52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A, Tsujino N, Funahashi H, Honda K, Guan JL, Wang QP et al (2002). Orexins activate histaminergic neurons via the orexin 2 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 290: 1237–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, McCormack S, Espana RA, Crocker A, Scammell TE (2006). Afferents to the orexin neurons of the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 494: 845–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.