Abstract

Background

Haemorrhagic shock is a major cause of death in the acute care setting. Since 2009, our emergency department has used intra-aortic balloon occlusion (IABO) catheters for resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA).

Methods

REBOA procedures were performed by one or two trained acute care physicians in the emergency room (ER) and intensive care unit (ICU). IABO catheters were positioned using ultrasonography. Collected data included clinical characteristics, haemorrhagic severity, blood cultures, metabolic values, blood transfusions, REBOA-related complications and mortality.

Results

Subjects comprised 25 patients (trauma, n = 16; non-trauma, n = 9) with a median age of 69 years and a median shock index of 1.4. REBOA was achieved in 22 patients, but failed in three elderly trauma patients. Systolic blood pressure significantly increased after REBOA (107 vs. 71 mmHg, p < 0.01). Five trauma patients (20 %) died in ER, and mortality rates within 24 h and 60 days were 20 % and 12 %, respectively. No REBOA-related complications were encountered. The total occlusion time of REBOA was significantly lesser in survivors than that in non-survivors (52 vs. 97 min, p < 0.01). Significantly positive correlations were found between total occlusion time of REBOA and shock index (Spearman’s r = 0.6) and lactate concentration (Spearman’s r = 0.7) in survivors.

Conclusion

REBOA can be performed in ER and ICU with a high degree of technical success. Furthermore, correlations between occlusion time and initial high lactate levels and shock index may be important because prolonged occlusion is associated with a poorer outcome.

Keywords: Emergency department, Shock, Intra-aortic balloon occlusion, Trauma, Gastrointestinal bleeding, Intensive care

Background

Trauma and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) are the most common causes of haemodynamic instability in patients with haemorrhage admitted to the emergency department (ED) and persistent haemorrhage is a major cause of death in acute care management [1–3]. Although the main aim of resuscitation is to stop the haemorrhage and restore circulating blood volume, persistent haemorrhage can be rapidly fatal. In such cases, conventional options for impending haemodynamic collapse are resuscitative thoracotomy (RT) and aortic clamping immediately performed in the emergency room (ER), particularly for uncontrolled torso haemorrhage or unstable pelvic fractures [4–8]. However, these procedures are invasive; therefore, resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) is increasingly used as an alternative to RT [9, 10]. The aim of REBOA is to maintain cerebral and coronary circulation to temporarily control arterial haemorrhage from the injured organ via occlusion using balloon inflation of the aortic lumen. Although a recent systematic review of REBOA in various clinical settings was found to successfully elevate central blood pressure in haemorrhagic shock, the effectiveness and indications for this intervention remain unclear [11]. Moreover, when applied as the only immediately available intervention for trauma patients with haemodynamic instability, REBOA was associated with increased mortality [12]. However, this study of trauma registry data was limited by the data elements collected in the registry, which mainly included age, vital signs and severity of injury. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective study of patients with haemorrhagic instability who underwent REBOA at a single emergency centre to determine the effect of REBOA on mortality and identify associations with vital indicators upon presentation at emergency facilities.

Methods

Patients and study design

The ethics committee of Tokyo Medical University Hachioji Medical Center approved the design of this retrospective study of patients with suspected haemorrhagic shock who subsequently underwent REBOA in ER or who were admitted to our intensive care unit (ICU) and subsequently developed haemorrhagic shock and underwent REBOA in ICU between September 2010 and September 2015. Patients with a systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90 mmHg or a shock index (SI; ratio of heart rate to SBP) ≥1.0 were considered to be in shock. We excluded patients aged <15 years and those who had cardiac arrest on admission or were diagnosed with any terminal disease during the study period.

Intra-aortic balloon occlusion catheter

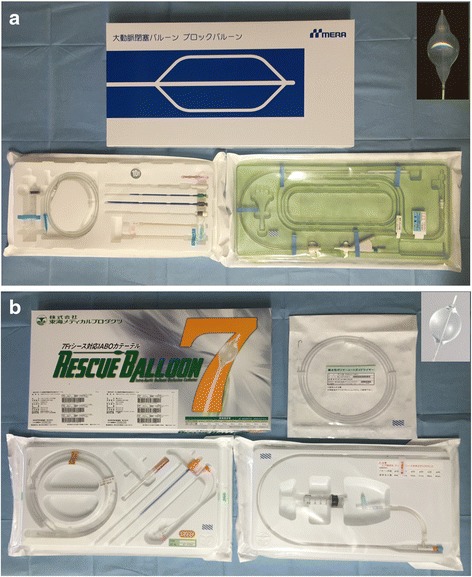

In our ER, 10 Fr. intra-aortic balloon occlusion (IABO) catheters (BLOCK BALLOON™; Senko Medical Instrument, Tokyo, Japan) were used until 2014. Since 2014, 7 Fr. IABO catheters (RESCUE BALLOON®; Tokai Medical Products, Tokyo, Japan) have been available. For percutaneous deployment of IABO catheters, all necessary guidewires, sharps and introducers are packaged together in the kit (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Intra-aortic balloon occlusion catheter available in Japan. a 10 Fr. BLOCK BALLOON™; b 7 Fr. RESCUE BALLOON®

Intervention

Treatment for haemorrhagic shock was performed on the basis of the Advanced Trauma Life Support resuscitation guidelines and the response to an initial fluid resuscitation with 1 L (since 9th edition) or 2 L (until 8th edition) of Ringer’s lactate. Acute care physicians categorised the patients into three categories based on subsequent haemodynamic responses to initial fluid resuscitation: a response group, showing immediate recovery from shock and remaining normotensive after initial fluid resuscitation; a transient-response group, showing recovery from shock, but an inability to remain normotensive after initial fluid resuscitation; and a non-response group, showing haemodynamic instability and no response to fluid resuscitation. Patients in the transient-response and non-response groups were considered to be haemodynamically unstable; therefore, empirical administration of blood and blood product transfusion were initiated earlier. Moreover, one or two acute care physicians performed all REBOA procedures. In our department, TJ was trained for ≥1 year as a member of the endovascular team in the Radiology Department of another university hospital, whereas all other acute care physicians in our ER performed sheath insertion using percutaneous femoral access >5 times under the guidance of TJ before performing REBOA.

For the REBOA procedure, a 10 Fr. (BLOCK BALLOON™) or 7 Fr. (RESCUE BALLOON®) sheath was first inserted into the femoral artery using the Seldinger method. In this study, all patients underwent sheath insertion via percutaneous femoral access. It was important that the sheath was passed over the wire into the femoral artery, and once the dilator and sheath had been advanced over the wire through the skin into the artery, the dilator was removed, leaving the sheath. When it was very difficult to pass the wire through either femoral artery, we discontinued the procedure and considered it to be a failed REBOA. After insertion of the femoral artery sheath, the IABO catheter was placed into the aorta and REBOA was performed. After insertion of the femoral artery sheath, an IABO catheter was inserted into the aorta, with selection of the aortic zone for occlusion according to the recommendations of Stannard et al. under ultrasonographic guidance [13]. Placement of the balloon is normally preformed in zone 1 (proximal part of the aorta, origin of the left subclavian artery to the celiac artery) in patients with suspected intra-abdominal haemorrhage, including UGIB. In patients with suspected haemorrhage from a confirmed pelvic fracture, the IABO catheters were placed in zone 3, (distal part of the aorta, lowest renal artery to the aortic bifurcation). IABO catheter positioning was performed under ultrasonographic guidance before REBOA placement and confirmed by portable chest or abdominal radiography in ER [14].

Data collection

The following characteristics were noted from the charts and radiographs of all patients with haemodynamic instability: age, sex, vital signs, clinical history, haemorrhagic severity, blood cultures, metabolic values [pH, lactate concentration and base excess], blood transfusion, REBOA-related complications and mortality. In patients admitted to ER or ICU, blood cultures and metabolic values were measured at the beginning of resuscitative intervention.

Statistical analyses

Data from all eligible patients were analysed. Continuous variables are shown as median values with interquartile ranges. Between-group differences were statistically assessed using the Mann − Whitney U test for continuous variables and the Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to identify correlations between the evaluated parameters. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism version 6.0a statistical software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Categorical variables were calculated as the ratio (percentage) of the frequency of occurrence. A probability (p) value of > 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Twenty-five patients (median age, 69 years; age range, 25 − 86 years; 62 % males), including 16 trauma and 9 non-trauma patients, were included in this study. The demographics and clinical characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1. The aetiologies of the trauma and non-trauma patients are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The REBOA success rate was 90 % in this study. Five trauma patients (20 %) died in ER. The mortality rates within 24 h and 60 days were 20 % (trauma, n = 4; non-trauma, n = 1) and 12 % (trauma, n = 1; non-trauma, n = 2), respectively. The complications observed with REBOA were not encountered.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients

| Variables | Trauma (n = 16) | Non-trauma (n = 9) | Total (n = 25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 72 (39–82) | 69 (63–72) | 69 (45–80) |

| Male, n (%) | 6 (38) | 9 (100)* | 15 (75) |

| Shock index, median (IQR) | 1.4 (1.1–1.5) | 1.6 (1.0–2.1) | 1.4 (1.1–1.16) |

| Injury severity score, median (IQR) | 41 (33–49) | - | - |

| Glasgow-Blatchford score, median (IQR) | - | - | - |

| Systolic blood pressure before REBOA (mmHg), median (IQR) | 78 (67–87) | 64 (61–77) | 71 (62–87) |

| Base excess (mmol/L), median (IQR) | -9.0 (-18.7–-6.3) | -11.5 (-14.6–-9.2) | -9.4 (-15.1–-6.4) |

| pH, median (IQR) | 7.33 (7.25–7.41) | 7.30 (7.23–7.38) | 7.32 (7.23–7.39) |

| Lactate (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 4.3 (3.2–9.0) | 6.3 (5.6–11.0) | 5.7 (3.7–11.0) |

| Prothrombin time (%), median (IQR) | 64.5 (46.5–79.5) | 67.0 (51.0–7.30) | 67.0 (48.0–77.0) |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (sec), median (IQR) | 56.3 (41.4–75.9) | 39.3 (35.3–64.5) | 53.4 (38.2–75.7) |

| Insertion at the ER, n (%) | 16 (100) | 6 (67) | 22 (88) |

| Failed REBOA, n (%) | 3 (19) | 0 | 3 (12) |

| Total occlusion time of REBOA (min), median (IQR) | 65 (57–99) | 55 (50–95) | 61 (51–98) |

| PRBC transfusion within 24 h (mL), median (IQR) | 1540 (840–2590) | 1960 (1400–2800) | - |

| FFP transfusion within 24 h (mL), median (IQR) | 720 (360–1440) | 900 (720–1440) | - |

| Outcomes, n (%) | |||

| Died at the ER | 5 (31) | 0 | 5 (20) |

| Died within 24 h | 4 (25) | 1 (11) | 5 (20) |

| Died within 2 months | 1 (6) | 2 (22) | 3 (12) |

IQR interquartile range, APACHE acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, ER emergency room, ICU intensive care unit and REBOA resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta; * p < 0.05 vs. trauma group

Table 2.

Characteristics of trauma patients

| No. | Age (y) | Sex | Mechanism | SI | ISS | Injury (AIS > 3) | Sheath insertion | Position (Zone) | Intervals for REBOA (min) | REBOA-related complications | Outcome | Cause of death | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Chest | Abdomen | Pelvis | Vertebral | Extremity | ER | >24 h | >2 months | |||||||||||

| 1 | 34 | F | Fall | 1.5 | 29 | - | + | - | Stable | - | + | Success | III | 65 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 2 | 45 | M | Laceration | 1.5 | 9 | - | - | - | - | - | Popliteal artery and vein tear | Success | III | 70 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 3 | 21 | M | TA (motorcycle) | 1.1 | 16 | - | - | Spleen: Grade IV | - | - | - | Success | II | 40 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 4 | 78 | F | TA (pedestrian) | 1.4 | 41 | + | + | - | Unstable | - | - | Success | III | 43 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | |

| 5 | 19 | F | TA (motorcycle) | 1.6 | 50 | - | + | Liver: Grade III | - | - | + | Success | I | 62 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 6 | 52 | M | Fall | 0.9 | 41 | + | + | Liver: Grade IV | - | + | - | Success | I | 48 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 7 | 71 | F | TA (pedestrian) | 1.0 | 57 | + | + | Spleen: Grade IV | Unstable | - | - | Success | I | 99 | None | Dead | - | - | Exsanguination |

| 8 | 85 | M | TA (motorcycle) | 1.4 | 41 | - | + | - | Unstable | - | - | Success | III | 60 | None | Dead | - | - | Exsanguination |

| 9 | 73 | F | Fall | 1.9 | 57 | + | + | - | Unstable | + | - | Success | II | 65 | None | Dead | - | - | Exsanguination |

| 10 | 86 | F | TA (pedestrian) | 1.1 | 48 | + | + | - | Unstable | - | - | Fail | II | - | None | Dead | - | - | Exsanguination |

| 11 | 82 | F | TA (pedestrian) | 1.1 | 50 | + | - | Spleen: Grade III | Unstable | - | + | Fail | II | - | None | Dead | - | - | Brain dead |

| 12 | 76 | F | TA (pedestrian) | 1.2 | 25 | - | - | Kidney: Grade IV | - | - | + | Fail | I | - | None | Alive | Dead | - | Exsanguination |

| 13 | 41 | F | Fall | 2.2 | 34 | - | + | Spleen: Grade III | Stable | - | - | Success | I | 135 | None | Alive | Dead | - | Exsanguination |

| 14 | 83 | F | Fall | 1.5 | 34 | + | Pulmonary vein injury | - | - | + | - | Success | I | 124 | None | Alive | Dead | - | ARDS |

| 15 | 84 | M | TA (pedestrian) | 1.2 | 41 | + | - | Spleen: Grade IV | - | - | - | Success | II | 57 | None | Alive | Dead | - | Brain dead |

| 16 | 24 | M | TA (motorcycle) | 1.3 | 41 | + | Brachial tear | - | - | - | - | Success | I | 110 | None | Alive | Alive | Dead | Brain dead |

SI shock index, ISS injury severity score, AIS abbreviated Injury Scale, REBOA resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion for the aorta, ER emergency room, TA traffic accident and ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome

Table 3.

Characteristics of non-trauma patients

| No. | Age | Sex | SI | Glasgow-Blatchford score | Clinical Rockall score | Diagnosis | Treatment | Sheath insertion | Position (Zone) | Sheath insertion | CPA during procedure | Intervals for REBOA (min) | REBOA-related complications | Outcome | Cause of death | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 24 h> | 3 months> | |||||||||||||||

| 17 | 68 | M | 1.6 | 13 | 3 | Gastric ulcer | Surgery | Success | I | Success | No | 46 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 18 | 50 | M | 1.0 | 12 | 2 | Gastric ulcer | AE (failed endoscopy) | Success | I | Success | No | 50 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 19 | 63 | M | 2.1 | 11 | 3 | Pseudo-aneurysm by pancreatic fistula | AE | Success | I | Success | Yes | 54 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 20 | 83 | M | 2.1 | 19 | 4 | Duodenal ulcer | Endoscopy | Success | I | Success | No | 140 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 21 | 36 | M | 0.7 | 7 | 3 | Gastric ulcer | Endoscopy | Success | I | Success | No | 20 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 22 | 69 | M | 2.8 | 17 | 3 | Gastric ulcer | Endoscopy | Success | I | Success | No | 57 | None | Alive | Alive | Alive | - |

| 23 | 72 | M | 1.2 | 9 | 3 | Gastric ulcer/ Cerebral infarction | AE (failed endoscopy) | Success | I | Success | Yes | 55 | None | Alive | Alive | Dead | Exsanguination |

| 24 | 69 | M | 1.7 | 12 | 3 | Duodenal ulcer | AE (failed endoscopy) | Success | I | Success | Yes | 95 | None | Alive | Alive | Dead | Ischemic encephalopathy |

| 25 | 80 | M | 0.8 | 14 | 5 | Duodenal ulcer | AE (failed endoscopy) | Success | I | Success | No | 145 | None | Alive | Dead | - | Exsanguination |

SI shock index, CPA cardiopulmonary arrest, REBOA resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta, ER emergency room; and AE angioembolizatoin

With regard to clinical characteristics, there were no significant differences in pH, lactate concentration, base excess, prothrombin time, activated partial thrombin time or injury severity score (ISS) between the survivors (n = 12) and non-survivors (n = 13). However, in trauma patients, there were significant differences in the revised trauma scale (RTS) and the trauma and injury severity scores (TRISS) between survivors and non-survivors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of survivors and non-survivors

| Variables | Survivors | Non-survivors | Total (n = 25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trauma, n (%) | 6 (38) | 10 (63) | - |

| Non-trauma, n (%) | 6 (67) | 3 (33) | - |

| Injury severity score, median (IQR) | 35 (19–41) | 41 (36–50) | - |

| Trauma and injury severity score, median (IQR) | 0.79 (0.46–0.94)* | 0.23 (0.15–0.44) | - |

| Revised trauma score, median (IQR) | 5.56 (5.17–6.43)* | 6.13 (4.03–6.38) | - |

| SBP before REBOA (mmHg), median (IQR) | |||

| Trauma | 87 (85–89) | 67 (60–74) | 78 (67–87) |

| Non-trauma | 63 (60–84) | 67 (65–72) | 64 (61–77) |

| Total | 86 (63–89) | 67 (61–75) | 71 (62–87) |

| SBP after REBOA (mmHg), median (IQR) | |||

| Trauma | 115 (106–123) | 78 (72–100) | 104 (78–118) |

| Non-trauma | 104 (93–123) | 112 (106–137) | 111 (97–127) |

| Total | 112 (101–126)** | 95 (74–111)** | 107 (90–118)** |

| ΔSBP (mmHg), median (IQR) | |||

| Trauma | 26 (19–46) | 11 (8–30) | 22 (11–32) |

| Non-trauma | 35 (28–37) | 49 (41–67) | 37 (32–49) |

| Total | 31 (22–41) | 30 (11–45) | 31 (19–46) |

| Blood transfusion (mL), median (IQR) | |||

| Trauma | 840 (840–2310) | 1960 (980–2450) | 1540 (840–2590) |

| Non-trauma | 2240 (1540–2730) | 1960 (1260–2380) | 1960 (1400–2800) |

| Total | 1680 (840–2800) | 1960 (840–2520) | 1960 (840–2800) |

| Occlusion time of IABO catheter (min), median (IQR) | |||

| Trauma | 55 (44–64) | 99 (63–117) | 65 (57–99) |

| Non-trauma | 54 (47–56) | 95 (75–120) | 55 (50–95) |

| Total | 52 (45–63)* | 97 (61–121) | 61 (51–98) |

IQR interquartile range, SBP systolic blood pressure, REBOA resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta, and IABO intra-aortic balloon occlusion; * p < 0.05 vs. non-survivors; ** p < 0.01 vs. SBP before REBOA in each group

Changes in acute care management with REBOA

Table 4 shows that SBP was significantly higher after initiation of REBOA. However, there were no significant differences in ΔSBP (SBP after REBOA − SBP before REBOA) or the volume of blood transfusion between the survivors and non-survivors.

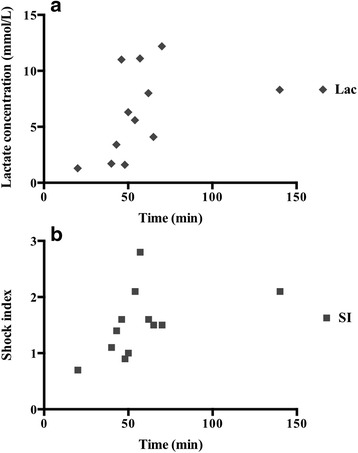

The total occlusion time of IABO catheters for the survivors was significantly shorter than for the non-survivors. Furthermore, strong positive correlations were found between total occlusion time and lactate concentration (Spearman’s r = 0.7, p = 0.02) and between total occlusion time and SI (Spearman’s r = 0.6, p = 0.04) in survivors (Fig. 2). We did not determine correlations between the occlusion time and any clinical variable in non-survivors.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between the total occlusion time of the intra-aortic balloon occlusion catheter and lactate concentration/shock index. a Lactate concentration; b shock index

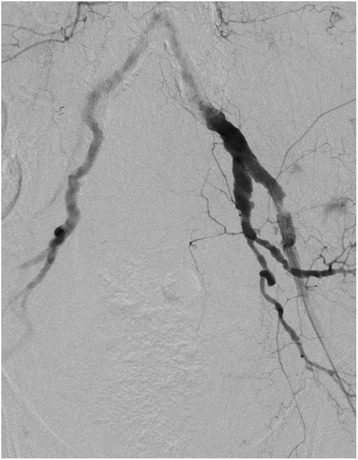

Analysis in cases of failed REBOA

The REBOA procedure failed in three patients (patients 10–12 in Table 2) because the wire could not be blindly passed through the femoral artery for sheath insertion in ER. Two of the three patients underwent RT in ER and one underwent REBOA in the angiography suite. All three patients were aged >75 years with severe visceral injuries and pelvic fractures; therefore, they underwent angio-embolization for the pelvic injuries and angiography revealed severe tortuosity or torsion of the femoral arteries (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Angiography of an elderly trauma patient with failed REBOA revealed severe tortuosity of the femoral arteries

Discussion

In the present study, we found that the total occlusion time of REBOA was longer in non-survivors than that in survivors with similar results between trauma and non-trauma patients. For trauma patients, our results were consistent with those reported by Saito et al. and Irahara et al. [7, 8]. Furthermore, the median REBOA occlusion time of approximately 60 min was similar between trauma and non-trauma patients. A recent study reported a REBOA duration of >90 min in an animal model of haemorrhage-induced organ dysfunction, particularly that of the kidneys and liver [15]. However, REBOA for 60 min was reportedly well tolerated in an animal model of persistent haemorrhagic shock [16]. Although it is important to shorten the occlusion time of REBOA as much as possible, our results strongly support those observed in these previous animal studies.

Norii et al. reported increased mortality using REBOA in trauma patients with a significantly higher ISS and lower RTS compared with patients who did not undergo REBOA treatment, thus REBOA is the only immediately available option for trauma patients with haemodynamic instability in Japan [12]. The Japanese trauma registry data were limited (i.e., age, vital signs, prehospital records, and severity of injury) and several details of the clinical parameters, such as blood cultures, lactate levels, the volume of fluid transfusion, and clinical occlusion time of REBOA, were not provided. We found significant correlations between the total occlusion time of REBOA and lactate concentration and SI measured at the beginning of resuscitation in survivors. Lactate concentration and SI are more effective indicators than vital signs, such as heart rate and SBP, to predict mortality of trauma patients [17, 18]. DeMuro et al. advocated an SI >0.8 to identify trauma patients that will require intervention for haemostasis [19]. For UGIB, a high SI is associated with fatal haemorrhage [20]. These parameters are useful to confirm suspected massive hemorrhage and may be helpful for future consideration for introducing REBOA. In the present study, three cases with a high SI experienced cardiac arrest before IABO catheter insertion and two died (multiple organ failure because of exsanguination and ischemic brain injury, respectively). We speculate that the early introduction of an IABO catheter without inflation for preventive reasons is warranted in patients with haemodynamic instability and a high SI and/or lactate concentration. The Japanese Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology in Emergency Critical Care and Trauma (DIRECT) is currently enrolling patients in a prospective multi-institutional trail (UMIN000015722) to examine the utility of and identify indications for REBOA.

A systematic review by Morrison et al. reported that REBOA successfully elevated central blood pressure in haemorrhagic shock in various clinical settings with [11]. Acute care physicians encounter haemorrhagic shock because of various causes, including ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, spontaneous bleeding caused by anticoagulation, and postpartum bleeding secondary to placenta previa or placenta abruption. Although endoscopic treatment for UGIB is generally acceptable, it can be difficult to completely achieve in some patients, and persistent haemorrhage can result in rapid death. A recent study demonstrated that advanced age, haemorrhagic shock, in-hospital bleeding, re-bleeding, and the need for surgery or other interventions are predictors of in-hospital mortality among patients with UGIB [21]. Moreover, patients with haemorrhagic shock on admission have an approximately 5-fold greater risk of intractability after initial endoscopic treatment, although mortality rates associated with UGIB have remained essentially unchanged at 5 % − 8 % [22]. Our results indicate the clinical safety and feasibility of REBOA in non-trauma patients, which have been insufficiently described in previous reports [23].

The complications observed with REBOA were caused by the insertion of the IABO catheter and femoral artery sheath. The major complications of IABO catheter insertion are vessel injuries (i.e., aortic dissection, rapture and perforation), embolisation, air emboli and peripheral ischaemia. However, Brenner et al. and Ogura et al. have reported no vessel injuries caused by an IABO catheter or inflated balloon in trauma patients [4, 7]. In the present study, there was no complication caused by the IABO catheter itself. In our department, we routinely use ultrasonography to guide positioning of the IABO catheter during procedures and evaluate catheter placement using portable radiography after catheter deployment. The findings of Guliani et al. support this result in their study showing that ultrasonography alone is as safe and accurate as fluoroscopy for positioning and deployment of an IABO catheter [14]. The major complications of sheath insertion are femoral artery injuries (i.e., pseudo-aneurysm, arteriovenous fistula and dissection) and lower limb ischaemia at the same site. Saito et al. reported a severe complication of lower limb ischaemia at the puncture site [7]. Therefore, we recommend careful consideration of ischaemic complications, particularly limb or organ ischaemia, during sheath insertion.

In the present study, we encountered difficulties with the insertions of a 10 Fr. sheath in three elderly trauma patients who were all women aged >75 years with severe tortuosity or torsion of the femoral arteries. Recent studies confirmed that the female sex and age >75 years are risk factors for femoral artery complications after endovascular treatment [24]. Other statistically significant risk factors included high body mass index, low platelet count, urgent procedures, increasing sheath size and administration of antithrombotic agents [25]. In such cases, performing endovascular procedures can be time-consuming and may be an issue with regard to the time required for resuscitation. In the acute care setting, the REBOA procedure is usually conducted blindly by acute care physicians, including emergency physicians and trauma surgeons, who must have sufficient knowledge of the risk factors and procedures associated with an endovascular approach. The development of new devices that do not require an oversized sheath, such as 10 Fr., or long guidewires is likely to reduce not only complications but also time to occlusion. In Japan, 7 Fr. IABO catheters have been clinically available since 2014, and we have used this device with technical success (100 %) by trained acute care physicians.

This study had several limitations, particularly the small number of evaluated patients sustaining different types of haemorrhagic shock, such as single trauma, multiple trauma and non-trauma (UGIB alone). Second, this was not a randomised, controlled trial or retrospective study using propensity scores because in the acute care setting, it is difficult to perform a randomised trial. Furthermore, use of a propensity score may be not suitable for a small sample size (trauma, n = 16 and non-trauma, n = 9) in a single emergency centre [26, 27]. Third, >30 % of the trauma patients in this study were aged ≥65 years and the clinical characteristics of such patients in Japan may differ from those in other countries [28]. Bernard et al. recently reported a population based analysis using Trauma Audit and Research Network data and the median age of trauma patients in whom may be potentially utilized REBOA was 43 years [29]. Thus, population based studies are beneficial to further evaluate the utility of REBOA for trauma populations.

Conclusion

In our experience, REBOA can be performed in ER and ICU and achieve a high degree of technical success. Furthermore, the correlations of occlusion time and initial high lactate levels and SI may be important because prolonged occlusion is associated with a poorer outcome. Further large clinical studies to identify patient subgroups with haemodynamic instability because of traumatic and non-traumatic haemorrhage that may benefit from REBOA are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Abbreviations

- ED

emergency department

- ER

emergency room

- IABO

intra-aortic balloon occlusion

- ICU

intensive care unit

- ISS

injury severity score

- REBOA

resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion for the aorta

- RT

resuscitative thoracotomy

- RTS

revised trauma score

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- SI

shock index

- TRISS

trauma and injury severity score

- UGIB

upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Footnotes

Competing interests

None. This manuscript has not been published previously and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Authors’ contributions

TJ conceived and designed the study. AI, ST, SM, OE, MM and YH provided technical support. OS gave the final approval of the version to be submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Dries DJ. The contemporary role of blood products and components used in trauma resuscitation. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:63. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-18-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baracat F, Moura E, Bernardo W, Pu LZ, Mendonça E, Moura D, et al. Endoscopic hemostasis for peptic ulcer bleeding: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2015. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Ferguson CB, Mitchell RM. Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: standard and new treatment.Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:607-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Brenner ML, Moore LJ, DuBose JJ, Tyson GH, McNutt MK, Albarado RP, et al. A clinical series of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for hemorrhage control and resuscitation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:506–11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31829e5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito N, Matsumoto H, Yagi T, Hara Y, Hayashida K, Motomura T, et al. Evaluation of the safety and feasibility of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:897–903. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irahara T, Sato N, Moroe Y, Fukuda R, Iwai Y, Unemoto K. Retrospective study of the effectiveness of Intra-Aotric Balloon Occlusion (IABO) for traumatic haemorrhagic shock. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogura T, Lefor AT, Nakano M, Izawa Y, Morita H. Nonoperative management of hemodynamically unstable abdominal trauma patients with angioembolization and resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:132–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore LJ, Brenner M, Kozar RA, Pasley J, Wade CE, Baraniuk MS, et al. Implementation of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta as an alternative to resuscitative thoracotomy for noncompressible truncal hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:523–32. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khorsandi M, Skouras C, Shah R. Is there any role for resuscitative emergency department thoracotomy in blunt trauma? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;16:509–16. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabinovici R, Bugaev N. Resuscitative thoracotomy: an update. Scand J Surg. 2014;103:112–9. doi: 10.1177/1457496913514735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison JJ, Galgon RE, Jansen JO, Cannon JW, Rasmussen TE, Eliason JL. A systematic review of the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in the management of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000913. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Norii T, Crandall C, Terasaka Y. Survival of severe blunt trauma patients treated with resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta compared with propensity score-adjusted untreated patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:721–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stannard A, Eliason JL, Rasmussen TE. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) as an adjunct for hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2011;71:1869–72. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31823fe90c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guliani S, Amendola M, Strife B, Morano G, Elbich J, Albuquerque F, et al. Central aortic wire confirmation for emergent endovascular procedures: As fast as surgeon-performed ultrasound. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:549–54. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markov NP, Percival TJ, Morrison JJ, Ross JD, Scott DJ, Spencer JR, et al. Physiologic tolerance of descending thoracic aortic balloon occlusion in a swine model of hemorrhagic shock. Surgery. 2013;153:848–56. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott DJ, Eliason JL, Villamaria C, Morrison JJ, Houston R, 4th, Spencer JR, et al. A novel fluoroscopy-free, resuscitative endovascular aortic balloon occlusion system in a model of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:122–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182946746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandromme MJ, Griffin RL, Weinberg JA, Rue LW, 3rd, Kerby JD. Lactate is a better predictor than systolic blood pressure for determining blood requirement and mortality: could prehospital measures improve trauma triage? J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:861–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandit V, Rhee P, Hashmi A, Kulvatunyou N, Tang A, Khalil M, et al. Shock index predicts mortality in geriatric trauma patients: an analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1111–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeMuro JP, Simmons S, Jax J, Gianelli SM. Application of the Shock Index to the prediction of need for hemostasis intervention. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1260–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakasone Y, Ikeda O, Yamashita Y, Kudoh K, Shigematsu K, Harada K. Shock index correlates with extravasation on angiographs of gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a logistics regression analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:861–5. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu PW, Ng EK, Cheung FK, Chan FK, Leung WK, Wu JC, et al. Predicting mortality in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers after therapeutic endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:311–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogasawara N, Mizuno M, Masui R, Kondo Y, Yamaguchi Y, Yanamoto K, et al. Predictive factors for intractability to endoscopic hemostasis in the treatment of bleeding gastroduodenal peptic ulcers in Japanese patients. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:162–73. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.2.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shigesato S, Shimizu T, Kittaka T, Akimoto H. Intra-aortic balloon occlusion catheter for treating hemorrhagic shock after massive duodenal ulcer bleeding. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:473. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayhan E, Isik T, Uyarel H, Ergelen R, Cicek G, Ghannadian B, et al. Femoral pseudoaneurysm in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: incidence, clinical course and risk factors. Int Angiol. 2012;31:579–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone PA, Campbell JE, AbuRahma AF. Femoral pseudoaneurysms after percutaneous access. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:1359–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pirracchio R, Resche-Rigon M, Chevret S. Evaluation of the propensity score methods for estimating marginal odds ratio in case of small sample size. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali MS, Groenwold RH, Belitser SV, Pestman WR, Hoes AW, Roes KC, et al. Reporting of covariate selection and balance assessment in propensity score analysis is suboptimal: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:112–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Japan Trauma Data Bank. Japan Trauma Data Bank Annual Report 2015 (2010-2014) English Version. https://www.jtcr-jatec.org/traumabank/dataroom/data/JTDB2015e.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2015.

- 29.Barnard EB, Morrison JJ, Mandureira RM, Lendrum R, Fragoso-Iñiguez M, Edwards A, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA): a population based gap analysis of trauma patients in England and Wales. Emerg Med J. 2015;32:926–32. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-205217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]