Abstract

Rgs2, a regulator of G proteins, lowers blood pressure by decreasing signaling through Gαq. Human patients expressing Met-Leu-Rgs2 (ML-Rgs2) or Met-Arg-Rgs2 (MR-Rgs2) are hypertensive relative to people expressing wild-type Met-Gln-Rgs2 (MQ-Rgs2). We found that wild-type MQ-Rgs2 and its mutant, MR-Rgs2, were destroyed by the Ac/N-end rule pathway, which recognizes Nα-terminally acetylated (Nt-acetylated) proteins. The shortest-lived mutant, ML-Rgs2, was targeted by both the Ac/N-end rule and Arg/N-end rule pathways. The latter pathway recognizes unacetylated N-terminal residues. Thus, the Nt-acetylated Ac-MX-Rgs2 (X = Arg, Gln, Leu) proteins are specific substrates of the mammalian Ac/N-end rule pathway. Furthermore, the Ac/N-degron of Ac-MQ-Rgs2 was conditional, and Teb4, an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane-embedded ubiquitin ligase, was able to regulate G protein signaling by targeting Ac-MX-Rgs2 proteins for degradation through their Nα-terminal acetyl group.

Regulators of G protein signaling (RGSs) bind to specific Gα subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins (Gαβγ) and accelerate the hydrolysis of Gα-bound guanosine tri-phosphate, thereby abrogating the signaling by G proteins (1–4). The mammalian Rgs2 protein regulates stress responses, translation, circadian rhythms, Ca2+ channels, specific hormones, and cardiovascular homeostasis (3–10). Blood pressure–increasing vasoconstrictors such as norepinephrine and angiotensin II are up-regulated by activated Gαq proteins, which are deactivated by Rgs2 (7). Both Rgs2−/− and heterozygous Rgs2+/− mice are strongly hypertensive (8, 9). Human patients with decreased Rgs2 signaling are hypertensive as well (10).

In some hypertensive patients, one of two Rgs2 genes encodes Met-Leu-Rgs2 (ML-Rgs2), in which Gln at position 2 of wild-type Met-Gln-Rgs2 (MQ-Rgs2) is replaced by Leu. Another hypertension-associated Rgs2 mutant is Met-Arg-Rgs2 (MR-Rgs2) (10). The Gln → Leu and Gln → Arg mutations are not detected in the general population (10). All three Rgs2 proteins are up-regulated by a proteasome inhibitor, which suggests that they may be targeted by a proteasome-dependent proteolytic system (11).

The N-end rule pathway recognizes proteins containing N-terminal (Nt) degradation signals called N-degrons, polyubiquitylates these proteins, and thereby causes their degradation by the proteasome (fig. S1) (12–20). The main determinant of an N-degron is a destabilizing Nt residue of a protein. Recognition components of the N-end rule pathway, called N-recognins, are E3 ubiquitin ligases that can target N-degrons. Regulated degradation of proteins by the N-end rule pathway mediates a broad range of biological functions (fig. S1) (12–20).

The N-end rule pathway consists of two branches. One branch, the Arg/N-end rule pathway, targets unacetylated destabilizing Nt residues (12, 14, 16). The Nt residues Arg, Lys, His, Leu, Phe, Tyr, Trp, and Ile, as well as Nt-Met [if it is followed by a bulky hydrophobic (Φ) residue], are directly recognized by N-recognins (16). In contrast, the unacetylated Asn, Gln, Asp, and Glu (as well as Cys, under some conditions) Nt residues are destabilizing, owing to their preliminary enzymatic modifications (fig. S1D).

The pathway’s other branch, called the Ac/N-end rule pathway, targets proteins through their Nα-terminally acetylated (Nt-acetylated) residues (fig. S1, A and C) (13, 15, 16). Degrons and E3 ubiquitin ligases of the Ac/N-end rule pathway are called Ac/N-degrons and Ac/N-recognins, respectively. Approximately 90% of human proteins are cotranslationally and irreversibly Nt-acetylated by ribosome-associated Nt-acetylases (21, 22). (In contrast, acetylation of internal Lys residues is reversible and largely posttranslational.) Doa10, an ER membrane-embedded E3 ubiquitin ligase of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (23, 24), functions as an Ac/N-recognin (13). Not4, a cytosolic and nuclear E3, is another yeast Ac/N-recognin (15).

The Arg/N-end rule pathway is present in all examined eukaryotes, from fungi to mammals and plants (fig. S1D) (12, 18, 19). In contrast, the Ac/N-end rule pathway (fig. S1C) has been identified in S. cerevisiae (13, 15, 16), but its presence in mammals and other multicellular eukaryotes has been conjectural so far.

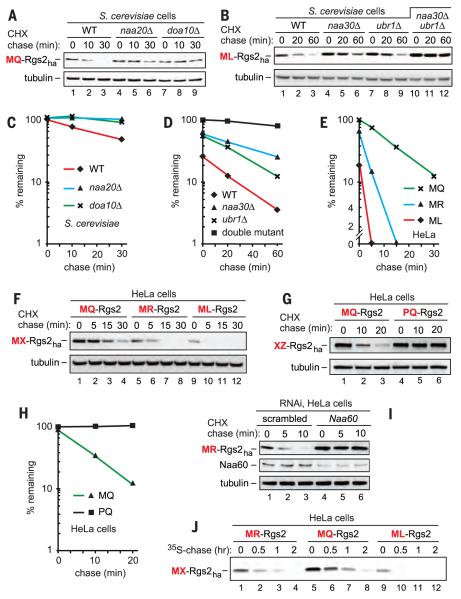

We began by subjecting wild-type human MQ-Rgs2 and its ML-Rgs2 mutant to cycloheximide (CHX) chases in yeast (13, 15, 16). The C-terminally HA (hemagglutinin)–tagged MQ-Rgs2ha was short-lived (t1/2 ≈ 30 min) in wild-type yeast and was stabilized in both naa20Δ and doa10Δ cells, which lacked, respectively, the cognate NatB Nt-acetylase and the Doa10 Ac/N-recognin (13) (Fig. 1, A and C, and figs. S1C and S2). Thus, in yeast, wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha was degraded largely by the Ac/N-end rule pathway (13, 15, 16).

Fig. 1. Rgs2 as an N-end rule substrate.

(A) CHX chases with wild-type human MQ-Rgs2ha in wild-type, naa20Δ, and doa10Δ S. cerevisiae. (B) As in (A) but with ML-Rgs2ha in wild-type, naa30Δ, ubr1Δ, and naa30Δ ubr1Δ strains. (C to E) Quantification of data in (A), (B), and (F), respectively. See the legend to fig. S3 for definitions of “100%” levels at zero time. (F) CHX chases with exogenously expressed MX-Rgs2ha (X = Arg, Gln, Leu) in HeLa cells. (G) As in (F) but with MQ-Rgs2ha versus PQ-Rgs2ha. (H) Quantification of data in (G). (I) CHX chases with exogenously expressed MR-Rgs2 in HeLa cells subjected to RNAi for a either a “scrambled” target or Naa60. (J) 35S-pulse chases with MX-Rgs2ha (X = Arg, Gln, Leu) in HeLa cells.

The mutant human ML-Rgs2ha was also short-lived in wild-type S. cerevisiae (t1/2 < 15 min) and was partially stabilized in both naa30Δ and ubr1Δ cells, which lacked, respectively, the cognate NatC Nt-acetylase and the Ubr1 N-recognin of the Arg/N-end rule pathway (Fig. 1, B and D, and figs. S1C, S2, and S3, A and D). ML-Rgs2ha was nearly completely stabilized in double-mutant naa30Δ ubr1Δ cells, including strongly elevated time-zero (pre-chase) levels of ML-Rgs2ha (Fig. 1, B and D, and fig. S3, A and D).

Many cellular proteins are partially Nt-acetylated (21). Non–Nt-acetylated yeast MΦ-type proteins are eliminated by the Arg/N-end rule pathway, whereas the Nt-acetylated counterparts of these proteins are destroyed by the Ac/N-end rule pathway (15, 16). This dual-targeting pattern was also observed with human ML-Rgs2ha (Fig. 1, B and D, and fig. S3, A and D). The contribution of the Ubr1 N-recognin to the degradation of ML-Rgs2ha (Fig. 1B and fig. S3A) indicated its incomplete Nt-acetylation in S. cerevisiae, similarly to results with natural MΦ-type yeast proteins (15, 16). Both wild-type MQ-Rgs2 and the second hypertension-associated mutant MR-Rgs2 were targeted (after their Nt-acetylation) solely by the Ac/N-end rule pathway, because the unacetylated Nt-Met followed by a non-Φ residue such as Gln or Arg is not recognized by the Arg/N-end rule pathway (in contrast to an MΦ-type protein such as ML-Rgs2ha) (fig. S1D) (16).

Wild-type MQ-Rgs2 is a predicted substrate of the NatB Nt-acetylase (fig. S2), in agreement with stabilization of MQ-Rgs2ha in naa20Δ S. cerevisiae, which lack NatB (Fig. 1, A and C). Using mass spectrometry (13), we analyzed the MQ-Rgs2 protein from human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells, confirming its Nt-acetylation (fig. S5A).

Considerably unequal levels of transiently expressed MQ-Rgs2ha, MR-Rgs2ha, and ML-Rgs2ha in human HeLa cells suggested their different stabilities (MQ > MR > ML) in these cells—an interpretation consistent with near-equal levels of the corresponding MX-Rgs2 mRNAs (fig. S4, C, F, and G). Indeed, CHX chases in HeLa cells showed that MR-Rgs2ha (t1/2 < 8 min) and ML-Rgs2ha (t1/2 < 5 min) were shorter-lived than the also unstable wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha (t1/2 ≈ 15 min) (Fig. 1, E and F, and fig. S3, B and E). The same (MQ > MR > ML) order of degradation rates was observed in 35S pulse chases of MQ-Rgs2ha, MR-Rgs2ha, and ML-Rgs2ha (Fig. 1J and fig. S4J).

In contrast to Nt-acetylatable (and therefore short-lived) wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha, the otherwise identical PQ-Rgs2ha (Pro-Gln-Rgs2ha), generated cotranslationally from MPQ-Rgs2ha, was neither Nt-acetylated nor recognized by the Arg/N-end rule pathway (figs. S1 and S2). PQ-Rgs2ha was long-lived in HeLa cells (Fig. 1, G and H). This result was an additional, conceptually independent piece of evidence for the targeting of Ac-MQ-Rgs2ha by the Ac/N-end rule pathway (fig. S1C).

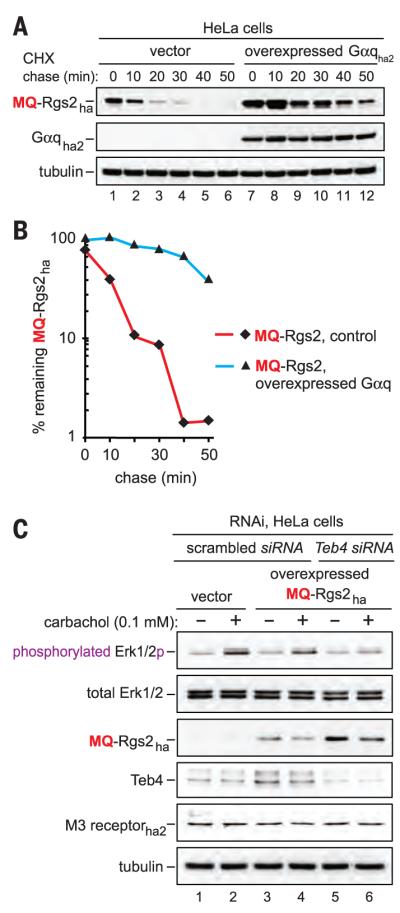

Remarkably, the exogenous (overexpressed) wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha was much shorter-lived (t1/2 ≈ 15 min) than the endogenous MQ-Rgs2 (t1/2 ≈ 3 hours) in HeLa cells that did not overexpress MQ-Rgs2ha (Fig. 1, E and F, Fig. 2B, and figs. S3, B and E, and S4, A and B). These results, with human cells, agreed with the recent demonstration of the biologically relevant conditionality of S. cerevisiae Ac/N-degrons (through their steric shielding in cognate protein complexes) (15). Given this understanding with natural Ac/N-end rule substrates in yeast (15, 16, 25), the present results (fig. S4, A and B) are what one would expect if Ac-MQ-Rgs2, in human cells that do not overexpress it, can be (reversibly) shielded from the Ac/N-end rule pathway soon after Nt-acetylation of MQ-Rgs2. This shielding would occur through formation of one or more physiologically relevant protective complexes between Ac-MQ-Rgs2 and its protein ligand(s). In contrast to the long half-life of the endogenous, “stoichiometrically” expressed MQ-Rgs2, its overexpression in HeLa cells would make the resulting “unprotectable” excess of Ac-MQ-Rgs2ha molecules vulnerable to destruction by the Ac/N-end rule pathway, thereby accounting for the large difference between the slowly degraded endogenous MQ-Rgs2 (in cells that do not overexpress MQ-Rgs2) and the short half-life of overexpressed MQ-Rgs2ha (fig. S4, A and B). Indeed, the short-lived MQ-Rgs2 was strongly stabilized by co-overexpression of one of its binding partners, the Gαq protein (Fig. 3, A and B).

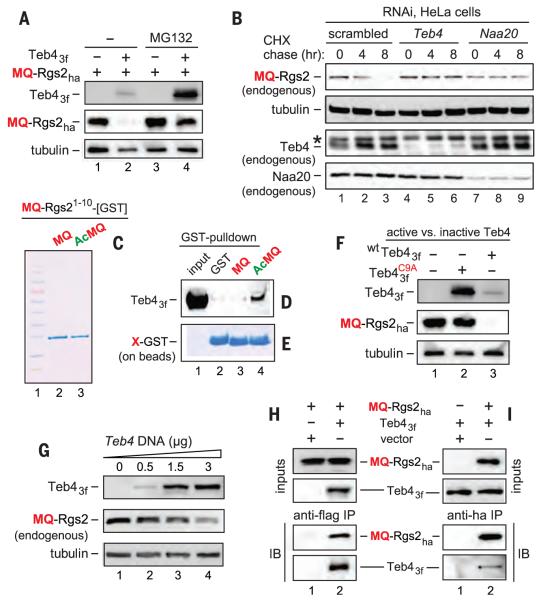

Fig. 2. Teb4 as an Ac/N-recognin.

(A) MQ-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells with or without Teb43f or the MG132 proteasome inhibitor. (B) CHX chases with endogenous MQ-Rgs2, Teb4, and Naa20 subjected to RNAi for a “scrambled” target, Teb4, or Naa20. The asterisk indicates a protein cross-reacting with anti-Teb4. (C) Molecular weight standards, purified MQ-Rgs21-10-GST, and purified Ac-MQ-Rgs21-10-GST, respectively. (D) Lane 1, Teb43f input; lanes 2 to 4, GST pull-downs with GST alone, MQ-Rgs21-10-GST, and Ac-MQ-Rgs21-10-GST, respectively. (E) As in (D) but Coomassie-stained GST fusions released from beads. (F) MQ-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells overexpressing wild-type Teb43f or . (G) Increases in Teb43f led to decreases in MQ-Rgs2ha. (H) HeLa cells expressing MQ-Rgs2ha alone (lane 1) or together with Teb43f (lane 2) were treated with a cell-penetrating cross-linker, followed by immunoprecipitations with anti-FLAG, reversal of cross-links, SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and immunoblotting with anti-HA and anti-FLAG. (I) As in (H) but Teb43f alone in lane 1, and immunoprecipitations with anti-HA.

Fig. 3. Gαq stabilizes Rgs2 while the Teb4-mediated degradation of Rgs2 increases signaling by Gαq.

(A) CHX chase of MQ-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells that did not express or overexpressed the HA-tagged Gαq. (B) Quantification of data in (A). See the legend to fig. S3 for definitions of “100%” levels at zero time. (C) HeLa cells were subjected to RNAi either for a “scrambled” target or for Teb4. The M3 receptor was transiently expressed either alone or together with MQ-Rgs2ha. The levels of indicated proteins, including the levels of either total Erk1/2 or the activated (specifically phosphorylated) Erk1/2p, were determined by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting of cell extracts that had been prepared 10 min after treatment of cells with carbachol.

A candidate Ac/N-recognin of the mammalian Ac/N-end rule pathway was Teb4, an ER membrane–embedded E3 ubiquitin ligase that polyubiquitylates proteins retrotranslocated from the ER. Teb4 is similar to the S. cerevisiae Doa10 Ac/N-recognin (13, 23, 24). We found that human Teb4 was indeed an Ac/N-recognin:

1) Transiently expressed MQ-Rgs2ha was up-regulated by a proteasome inhibitor, whereas coexpression of human Teb4 (Teb43f) and MQ-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells down-regulated MQ-Rgs2ha (Fig. 2, A and F). In addition, incrementally higher levels of Teb43f resulted in incrementally lower levels of endogenous MQ-Rgs2 (Fig. 2G).

2) The level of MQ-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells was not decreased when MQ-Rgs2ha was coexpressed with , a missense mutant that is inactive as a ubiquitin ligase (24) (Fig. 2F). Analogous assays with MR-Rgs2ha and ML-Rgs2ha gave similar results (fig. S4, D and E).

3) The in vivo polyubiquitylation of MQ-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells was increased by coexpression of Teb43f, but not by coexpression of the mutant (fig. S3F).

4) In CHX chases, endogenous MQ-Rgs2 was stabilized by RNA interference (RNAi)–mediated knockdowns of either endogenous Teb4 E3 or endogenous cognate NatB Nt-acetylase (Fig. 2B and fig. S4A). Similar results were obtained with exogenous (overexpressed) MQ-Rgs2ha, confirming the targeting of MQ-Rgs2 by Teb4 and indicating that this targeting required Nt-acetylation of MQ-Rgs2 by the NatB Nt-acetylase (Fig. 2B and fig. S4, A and B). In addition, overexpressed (hypertension-associated) MR-Rgs2ha as well as the engineered MK-Rgs2ha (which has a different basic residue at position 2) were stabilized by RNAi-based knockdown of Naa60, the catalytic subunit of cognate NatF Nt-acetylase (21, 22), but these MX-Rgs2ha proteins were not stabilized by knockdown of the noncognate NatB (Naa20) Nt-acetylase (Fig. 1I and fig. S4, H and I).

5) Cross-linking and coimmunoprecipitation experiments indicated that Teb4 interacted with MQ-Rgs2 (more accurately, with Nt-acetylated Ac-MQ-Rgs2ha, as shown below) (Fig. 2, H and I).

6) PQ-Rgs2ha was neither Nt-acetylated nor recognized by the Arg/N-end rule pathway and was a long-lived protein, in contrast to short-lived MQ-Rgs2ha (Fig. 1, G and H, and fig. S1C). In agreement with these in vivo results, Teb43f coimmunoprecipitated with MQ-Rgs2ha (Ac-MQ-Rgs2ha) but not with PQ-Rgs2ha (Fig. 2, H and I, and fig. S3C).

7) Glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays showed that Teb4f interacted with Ac-MQ-Rgs21-10-GST (containing the first 10 residues of wild-type human Rgs2) but not with MQ-Rgs21-10-GST or GST alone, indicating that the binding of Teb4 to Ac-MQ-Rgs21-10-GST required its Nt-acetyl group (Fig. 2, C to E, and fig. S5B).

By increasing the rate of deactivation of Gαq, Rgs2 can down-regulate Gαq-activated protein kinases, including the growth-promoting kinase Erk1/2 (3, 4). We asked whether the Teb4 Ac/N-recognin could regulate the activation of Erk1/2 through the degradation of Nt-acetylated Ac-MQ-Rgs2. The Gαq-coupled M3 acetylcholine receptor was expressed in HeLa cells either alone or together with MQ-Rgs2ha. By activating the M3 receptor–coupled Gαq, the agonist carbachol strongly increased the level of activated Erk1/2 [measured by detecting its phosphorylation by the “upstream” Mek1/Mek2 kinases (3, 4)]. As predicted by the model in which the Teb4-Rgs2 circuit regulates the activation of Erk1/2, this effect of carbachol on Erk1/2 was decreased in cells that also expressed MQ-Rgs2ha and was further diminished upon RNAi-mediated knockdown of Teb4—a change that stabilized MQ-Rgs2ha and thereby further elevated its level (Fig. 3C).

Thus, wild-type human Ac-MQ-Rgs2, its hypertension-associated natural mutants Ac-ML-Rgs2 and Ac-MR-Rgs2, and its engineered mutant Ac-MK-Rgs2 are conditionally short-lived physiological substrates of the mammalian Ac/N-end rule pathway, and the Teb4 ubiquitin ligase acts as an Ac/N-recognin of this pathway. Teb4 promotes G protein signaling by destroying the Ac-MX-Rgs2 proteins (X = Arg, Gln, Leu), which are targeted for degradation through their Nα-terminal acetyl group. The faster degradation of ML-Rgs2 and MR-Rgs2 (relative to wild-type MQ-Rgs2) and their consequently lower levels can account, at least in part, for the hypertensive phenotypes of these mutants. The resulting understanding of Rgs2 with respect to the N-end rule pathway is summarized in fig. S6.

Identification of Teb4 as an Ac/N-recognin of the mammalian Ac/N-end rule pathway suggests that some previously characterized substrates of Teb4, including specific transmembrane proteins [(23, 24, 26) and references therein], may be recognized by Teb4 at least in part though their Nt-acetylated Nt residues (Ac/N-degrons)—a testable proposition.

More than 30 human proteins contain an RGS-type domain (fig. S7) (3, 4). The N-terminal Cys residue, a common feature of Rgs4, Rgs5, and Rgs16, can be oxidized in vivo by nitric oxide (NO) and oxygen. The resulting Nt-arginylation of oxidized Cys and the ensuing degradation of these RGSs by the Arg/N-end rule pathway mediate its previously described function as a sensor of NO and oxygen (fig. S1D) [reviewed in (12, 18, 19)]. Our study identified Rgs2 (MQ-Rgs2) as a different kind of N-end rule substrate, an Nt-acetylated one. Given their inferred N-terminal sequences, it is possible, indeed likely, that a number of other mammalian RGS proteins (in addition to Rgs2, Rgs4, Rgs5, and Rgs16) may also prove to be substrates of either the Ac/N-end rule pathway or the Arg/N-end rule pathway, or both of these proteolytic systems (fig. S7).

Many cellular proteins contain Ac/N-degrons, having acquired them during synthesis (13). These degradation signals, recognized by the Ac/N-end rule pathway, tend to be conditional, owing to their shielding in cognate protein complexes (15). In addition, the Ac/N-end rule pathway and the Arg/N-end rule pathway are functionally complementary (16). It could therefore be possible to control the levels (and thus the activities) of many different proteins therapeutically, including Rgs2 and other RGSs, by modulating their Ac/N-degrons or specific components of the Ac/N-end rule pathway.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Conditional removal of N-terminal methionine from nascent proteins, their N-terminal acetylation, and the N-end rule pathway.

(A) N-terminal processing of nascent proteins by Nα-terminal acetylases (Nt-acetylases) and Met-aminopeptidases (MetAPs). “Ac” denotes the Nα-terminal acetyl moiety. M, methionine (Met) residue. X and Z, single-letter abbreviations for any amino acid residue. Yellow ovals denote the rest of a protein molecule. MetAPs cotranslationally remove N-terminal Met from a nascent protein unless the side chain of a residue at position 2 is bulkier than Val, in which case Met is retained (12, 34).

(B) Functional complementarity between the Arg/N-end rule pathway and the Ac/N-end rule pathway for proteins bearing the N-terminal MΦ motif, i.e., unacetylated N-terminal Met followed by a bulky hydrophobic (Φ) residue. This motif is targeted by the Arg/N-end rule pathway (16). Because the Met-Φ motif is also a substrate of the NatC Nt-acetylase (Fig. S2), Met-Φ proteins are usually Nt-acetylated at least in part, thereby acquiring the previously characterized Ac/N-degrons (13, 16). Thus, both Nt-acetylated and unacetylated versions of the same Met-Φ protein can be destroyed, either by the Ac/N-end rule pathway or by the “complementary” Arg/N-end rule pathway (16).

(C, D) The mammalian N-end rule pathway. The main determinant of an N-degron is a destabilizing N-terminal residue of a protein. Recognition components of the N-end rule pathway, called N-recognins, are E3 ubiquitin ligases that can recognize N-degrons.

Regulated degradation of proteins or their fragments by the N-end rule pathway mediates a strikingly broad range of functions, including the sensing of heme, nitric oxide, oxygen, and short peptides; control of protein quality and subunit stoichiometries, including the elimination of misfolded proteins; regulation of signaling by G proteins; repression of neurodegeneration; regulation of apoptosis, chromosome cohesion/segregation, transcription, and DNA repair; control of peptide import; regulation of meiosis, autophagy, immunity, fat metabolism, cell migration, actin filaments, cardiovascular development, spermatogenesis, and neurogenesis; the functioning of adult organs, including the brain, muscle and pancreas; and the regulation of many processes in plants (references (12-14, 16, 18, 20, 35-88) and references therein). In eukaryotes, the N-end rule pathway consists of two branches, the Ac/N-end rule pathway and the Arg/N-end rule pathway.

(C) The Ac/N-end rule pathway. This diagram illustrates the mammalian Ac/N-end rule pathway through extrapolation from its S. cerevisiae version. As described in the main text, the Ac/N-end rule pathway has been identified only in S. cerevisiae (13, 15, 16), i.e., the presence of this pathway in mammals and other multicellular eukaryotes was conjectural, until the present work. Red arrow on the left indicates the removal of N-terminal Met by Met-aminopeptidases (MetAPs). N-terminal Met is retained if a residue at position 2 is nonpermissive (too large) for MetAPs. If the retained N-terminal Met or N-terminal Ala, Ser, Thr are followed by acetylation-permissive residues, the above N-terminal residues are Nα-terminally acetylated (Nt-acetylated) by ribosome-associated Nt-acetylases (21, 89, 90). Nt-terminal Val and Cys are Nt-acetylated relatively rarely, while N-terminal Pro and Gly are almost never Nt-acetylated. (N-terminal Gly is often N-myristoylated.) N-degrons and N-recognins of the Ac/N-end rule pathway are called Ac/N-degrons and Ac/N-recognins, respectively (12). The term “secondary” refers to Nt-acetylation of a destabilizing N-terminal residue before a protein can be recognized by a cognate Ac/N-recognin. As described in the main text, the human Teb4 E3 ubiquitin ligase was identified, in the present study, as an Ac/N-recognin of the mammalian Ac/N-end rule pathway. Natural Ac/N-degrons are regulated at least in part by their reversible steric shielding in protein complexes (15, 16).

(D) The Arg/N-end rule pathway. The prefix “Arg” in the pathway’s name refers to N-terminal arginylation (Nt-arginylation) of N-end rule substrates by the Ate1 arginyltransferase (R-transferase), a significant feature of this proteolytic system. The Arg/N-end rule pathway targets specific unacetylated N-terminal residues. In the yeast S. cerevisiae, the Arg/N-end rule pathway is mediated by the Ubr1 N-recognin, a 225 kDa RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase and a part of the targeting apparatus comprising a complex of the Ubr1-Rad6 and Ufd4-Ubc4/5 holoenzymes (12, 14, 18). In multicellular eukaryotes several functionally overlapping E3 ubiquitin ligases (Ubr1, Ubr2, Ubr4, Ubr5) function as N-recognins of this pathway. An N-recognin binds to the “primary” destabilizing N-terminal residues Arg, Lys, His, Leu, Phe, Tyr, Trp and Ile. In contrast, the N-terminal Asn, Gln, Asp, and Glu residues (as well as Cys, under some metabolic conditions) are destabilizing owing to their preliminary enzymatic modifications. These modifications include the Nt-deamidation of N-terminal Asn and Gln by the Ntan1 and Ntaq1 Nt-amidases, respectively, and the Nt-arginylation of N-terminal Asp and Glu by the Ate1 R-transferase, which can also Nt-arginylate oxidized Cys, either Cys-sulfinate or Cys-sulfonate. They can form in animal and plant cells through oxidation of Cys by nitric oxide (NO) and oxygen, and also by N-terminal Cys-oxidases (19, 44, 52, 59, 61, 91-93). In addition to its type-1 and type-2 binding sites that recognize, respectively, the basic and bulky hydrophobic unacetylated N-terminal residues, an N-recognin such as Ubr1 contains other substrate-binding sites as well. These sites recognize substrates that are targeted through their internal (non-N-terminal) degrons, as indicated on the diagram (12). Hemin (Fe3+-heme) binds to the Ate1 R-transferase, inhibits its Nt-arginylation activity and accelerates its in vivo degradation. Hemin also binds to Ubr1 (and apparently to other N-recognins as well) and alters its functional properties, in ways that remain to be understood (43). As shown in the diagram, the unacetylated Met of the N-terminal MΦ motif is recognized by both yeast and mammalian Ubr1; this capability greatly expands the substrate range of the Arg/N-end rule pathway (16).

Fig. S2. Specificities and subunit compositions of Nα-terminal acetylases (Nt-acetylases).

(A) Substrate specificities of S. cerevisiae Nt-acetylases. “Ac” denotes the Nα-terminal acetyl moiety. The bulk of Nt-acetylases are associated with ribosomes (94, 95). The specificities of mammalian Nt-acetylases are similar to those of their yeast counterparts, but an individual mammalian genome encodes more than ten Nt-acetylases, in contrast to four in S. cerevisiae. Some mammalian Nt-acetylases, such as NatF (its catalytic subunit is called Naa60 (see fig. S4H, I)) (22), can Nt-acetylate N-terminal motifs that include Met-Lys or Met-Arg, which are rarely if ever Nt-acetylated in S. cerevisiae. This compilation of Nt-acetylases and their specificities is derived from data in the literature ((21, 89, 90, 96-108) and references therein).

(B) Subunits of S. cerevisiae Nt-acetylases. This paper employs the revised nomenclature for subunits of Nt-acetylases (109) and cites older names of these subunits in parentheses.

Fig. S3. The targeting of MX-Rgs2 proteins by the yeast and human Ac/N-end rule and Arg/N-end rule pathways.

(A) CHX chases with the hypertension-associated mutant human ML-Rgs2ha in wild-type, naa30Δ, ubr1Δ, and naa30Δ ubr1Δ S. cerevisiae.

(B) As in A but in human HeLa cells with wild-type human MQ-Rgs2ha and hypertension-associated mutants MR-Rgs2ha and ML-Rgs2ha.

(C) HeLa cells expressing MQ-Rgs2ha or PQ-Rgs2ha together with Teb43f were treated with a cell-penetrating crosslinker, followed by immunoprecipitations with anti-flag, reversal of crosslinks, SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting with anti-ha and anti-flag (see also Fig. 2H and Materials and Methods). Note the coimmunoprecipitation of MQ-Rgs2ha with Teb43f, and the absence of coimmunoprecipitation of PQ-Rgs2ha.

(D) Quantification of data in A. 100% corresponded to the zero-time level of ML-Rgs2ha in naa30Δ ubr1Δ S. cerevisiae.

(E) Quantification of data in B. 100% corresponded to the zero time level of PQ-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells.

In every set of degradation curves shown in this figure and in the main Figs. 1 and 3, 100% at zero time was chosen to correspond to the relative initial level of the most slowly degraded test protein in a given set. Panel A (quantified in D) and panel B (quantified in E) show the results of CHX-chases that were independently carried out counterparts of CHX-chases that are shown in the main Fig. 1B (quantified in D) and 1F (quantified in E), respectively. These comparisons illustrate qualitative reproducibility of independently generated data (particularly the robustly reproduced order of metabolic stabilities of specific test proteins in specific genetic backgrounds), which differed in relatively minor aspects of corresponding degradation curves. In our extensive experience with repeated CHX-chases and 35S-pulse-chases in either S. cerevisiae or HeLa cells, a strictly quantitative reproducibility of independently produced and measured chase-degradation patterns remains the aim to be reached.

(F) Extracts from HeLa cells expressing MQ-Rgs2ha in the presence or absence of coexpressed Teb43f or and in the presence of the MG132 proteasome inhibitor, as indicated. MQ-Rgs2ha was immunoprecipitated from extracts using anti-ha antibody, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody to detect polyubiquitin chains linked to MQ-Rgs2, and with anti-flag, anti-ha and anti-tubulin antibodies as well, as shown.

Fig. S4. Degradation assays with MX-Rgs2 proteins in HeLa cells subjected to RNAi of specific Nt-acetylases and Teb4.

(A) CHX-chases with endogenous (not overexpressed) MQ-Rgs2 in HeLa cells subjected to RNAi-mediated knockdowns of endogenous Teb4 or Naa20 (NatB).

(B) Same as in A but CHX-chases with transiently expressed (exogenous) MQ-Rgs2ha.

(C) Relative steady-state levels of exogenous wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha and its MR-Rgs2ha and ML-Rgs2ha mutants in HeLa cells transfected with equal amounts of MX-Rgs2ha plasmids.

(D) ML-Rgs2ha expressed in HeLa cells in the presence of the coexpressed wild-type Teb43f or . Note a strong decrease of ML-Rgs2ha in the presence of wild-type Teb43f but not in the presence of its inactive missense mutant . Note also a much lower steady-state level of active Teb43f (in comparison to the inactive ), owing to the previously described self-targeting of active Teb4 for degradation (24).

(E) Same as in D but with MR-Rgs2ha.

(F) Quantification of data in C (relative levels of the three MX-Rgs2ha proteins).

(G) Same as in F but quantification, using qRT-PCR, of the relative levels of mRNAs encoding the three MX-Rgs2ha proteins. Standard errors of means (SEMs), with qRT-PCR assays in triplicate for each sample, are indicated as well.

(H) Steady-state levels of transiently expressed (exogenous) MR-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells subjected to RNAi-mediated knockdowns of either endogenous Naa60, the cognate (for MR-Rgs2ha) NatF Nt-acetylase, or endogenous Naa20, the non-cognate (for MR-Rgs2ha) NatB Nt-acetylase. Note the increase in MR-Rgs2ha in response to RNAi of Naa60 but not of Naa20.

(I) Same as in H but with MK-Rgs2ha, a derivative of wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha not encountered, thus far, among human patients, that contained another basic residue at position 2.

(J) 35S-pulse-chases with MX-Rgs2ha (X=R, Q, L) in HeLa cells.

Fig. S5. Mass spectrometric analyses of Nt-acetylation of MQ-Rgs2 and MQ-Rgs21-10-[GST]. (A) Wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha purified from human HEK293 cells is Nt-acetylated. (B) Non-Nt-acetylated (upper panel) and Nt-acetylated MQ-Rgs21-10-[GST] fusion (lower panel) purified from E. coli that either lacked or expressed, respectively, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe NatB Nt-acetylase (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. S6. Rgs2, Teb4, N-terminal acetylation, and the N-end rule pathway. Rgs2 and Teb4 are, respectively, a substrate and Ac/N-recognin of the mammalian Ac/N-end pathway. Only some Rgs2-regulated processes (including the Gαq-mediated activation of Erk1/2 kinase) are shown. Both wild-type MQ-Rgs2 and its hypertension-associated mutant MR-Rgs2 (the latter is not shown) are Nt-acetylated and conditionally destroyed by the Teb4-mediated Ac/N-end rule pathway. In contrast, another hypertension-associated mutant, ML-Rgs2, is targeted by both the Ac/N-end rule pathway and the Arg/N-end rule pathway (see the main text) (fig. S1C, D). Some abbreviations: IP3, inositol trisphosphate. DAG, diacyglycerol.

Fig. S7. Mammalian RGS proteins as identified or predicted N-end rule substrates.

Human RGS proteins as identified or possible (predicted) substrates of either the Ac/N-end rule pathway, or the Arg/N-end rule pathway, or both pathways at the same time, depending on the Nt-acetylation status of a specific RGS protein. See also the main text.

Table S1. S. cerevisiae strains used in this study.

Table S2. Plasmids used in this study.

Table S3. Some PCR primers used in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Neubig, M. Mulvihill, and E. Wiertz for gifts of plasmids, and K. Piatkov for helpful suggestions. Supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of the Korea government (MSIP) (NRF-2011-0021975, NRF-2012R1A4A1028200, NRF-2013R1A1A2012529) and BK21 Plus Program (C.-S.H.), and by NIH grants DK039520 and GM031530 (A.V.).

Footnotes

www.sciencemag.org/content/347/6227/1249/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S7

Tables S1 to S3

References (27–110)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Lefkowitz RJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:6366–6378. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobilka B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:6380–6388. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sjögren B, Blazer LL, Neubig RR. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2010;91:81–119. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(10)91004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimple AJ, Bosch DE, Giguère PM, Siderovski DP. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011;63:728–749. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chidiac P, Sobiesiak AJ, Lee KN, Gros R, Nguyen CH. Cell. Signal. 2014;26:1226–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuo M, Coon SL, Klein DC. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1392–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nance MR, et al. Structure. 2013;21:438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang KM, et al. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1506–1512. doi: 10.1038/nm958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heximer SP, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:445–452. doi: 10.1172/JCI15598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang J, et al. J. Hypertens. 2005;23:1497–1505. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000174606.41651.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodenstein J, Sunahara RK, Neubig RR. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:1040–1050. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varshavsky A. Protein Sci. 2011;20:1298–1345. doi: 10.1002/pro.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang C-S, Shemorry A, Varshavsky A. Science. 2010;327:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1183147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang C-S, Shemorry A, Auerbach D, Varshavsky A. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:1177–1185. doi: 10.1038/ncb2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shemorry A, Hwang C-S, Varshavsky A. Mol. Cell. 2013;50:540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H-K, et al. Cell. 2014;156:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JM, Hwang CS. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1366–1367. doi: 10.4161/cc.28751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tasaki T, Sriram SM, Park KS, Kwon YT. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:261–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051710-093308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbs DJ, Bacardit J, Bachmair A, Holdsworth MJ. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mogk A, Schmidt R, Bukau B. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starheim KK, Gevaert K, Arnesen T. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012;37:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Damme P, et al. PLOS Genet. 2011;7:e1002169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreft SG, Wang L, Hochstrasser M. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:4646–4653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassink G, et al. Biochem. J. 2005;388:647–655. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monda JK, et al. Structure. 2013;21:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zelcer N, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014;34:1262–1270. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01140-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Conditional removal of N-terminal methionine from nascent proteins, their N-terminal acetylation, and the N-end rule pathway.

(A) N-terminal processing of nascent proteins by Nα-terminal acetylases (Nt-acetylases) and Met-aminopeptidases (MetAPs). “Ac” denotes the Nα-terminal acetyl moiety. M, methionine (Met) residue. X and Z, single-letter abbreviations for any amino acid residue. Yellow ovals denote the rest of a protein molecule. MetAPs cotranslationally remove N-terminal Met from a nascent protein unless the side chain of a residue at position 2 is bulkier than Val, in which case Met is retained (12, 34).

(B) Functional complementarity between the Arg/N-end rule pathway and the Ac/N-end rule pathway for proteins bearing the N-terminal MΦ motif, i.e., unacetylated N-terminal Met followed by a bulky hydrophobic (Φ) residue. This motif is targeted by the Arg/N-end rule pathway (16). Because the Met-Φ motif is also a substrate of the NatC Nt-acetylase (Fig. S2), Met-Φ proteins are usually Nt-acetylated at least in part, thereby acquiring the previously characterized Ac/N-degrons (13, 16). Thus, both Nt-acetylated and unacetylated versions of the same Met-Φ protein can be destroyed, either by the Ac/N-end rule pathway or by the “complementary” Arg/N-end rule pathway (16).

(C, D) The mammalian N-end rule pathway. The main determinant of an N-degron is a destabilizing N-terminal residue of a protein. Recognition components of the N-end rule pathway, called N-recognins, are E3 ubiquitin ligases that can recognize N-degrons.

Regulated degradation of proteins or their fragments by the N-end rule pathway mediates a strikingly broad range of functions, including the sensing of heme, nitric oxide, oxygen, and short peptides; control of protein quality and subunit stoichiometries, including the elimination of misfolded proteins; regulation of signaling by G proteins; repression of neurodegeneration; regulation of apoptosis, chromosome cohesion/segregation, transcription, and DNA repair; control of peptide import; regulation of meiosis, autophagy, immunity, fat metabolism, cell migration, actin filaments, cardiovascular development, spermatogenesis, and neurogenesis; the functioning of adult organs, including the brain, muscle and pancreas; and the regulation of many processes in plants (references (12-14, 16, 18, 20, 35-88) and references therein). In eukaryotes, the N-end rule pathway consists of two branches, the Ac/N-end rule pathway and the Arg/N-end rule pathway.

(C) The Ac/N-end rule pathway. This diagram illustrates the mammalian Ac/N-end rule pathway through extrapolation from its S. cerevisiae version. As described in the main text, the Ac/N-end rule pathway has been identified only in S. cerevisiae (13, 15, 16), i.e., the presence of this pathway in mammals and other multicellular eukaryotes was conjectural, until the present work. Red arrow on the left indicates the removal of N-terminal Met by Met-aminopeptidases (MetAPs). N-terminal Met is retained if a residue at position 2 is nonpermissive (too large) for MetAPs. If the retained N-terminal Met or N-terminal Ala, Ser, Thr are followed by acetylation-permissive residues, the above N-terminal residues are Nα-terminally acetylated (Nt-acetylated) by ribosome-associated Nt-acetylases (21, 89, 90). Nt-terminal Val and Cys are Nt-acetylated relatively rarely, while N-terminal Pro and Gly are almost never Nt-acetylated. (N-terminal Gly is often N-myristoylated.) N-degrons and N-recognins of the Ac/N-end rule pathway are called Ac/N-degrons and Ac/N-recognins, respectively (12). The term “secondary” refers to Nt-acetylation of a destabilizing N-terminal residue before a protein can be recognized by a cognate Ac/N-recognin. As described in the main text, the human Teb4 E3 ubiquitin ligase was identified, in the present study, as an Ac/N-recognin of the mammalian Ac/N-end rule pathway. Natural Ac/N-degrons are regulated at least in part by their reversible steric shielding in protein complexes (15, 16).

(D) The Arg/N-end rule pathway. The prefix “Arg” in the pathway’s name refers to N-terminal arginylation (Nt-arginylation) of N-end rule substrates by the Ate1 arginyltransferase (R-transferase), a significant feature of this proteolytic system. The Arg/N-end rule pathway targets specific unacetylated N-terminal residues. In the yeast S. cerevisiae, the Arg/N-end rule pathway is mediated by the Ubr1 N-recognin, a 225 kDa RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase and a part of the targeting apparatus comprising a complex of the Ubr1-Rad6 and Ufd4-Ubc4/5 holoenzymes (12, 14, 18). In multicellular eukaryotes several functionally overlapping E3 ubiquitin ligases (Ubr1, Ubr2, Ubr4, Ubr5) function as N-recognins of this pathway. An N-recognin binds to the “primary” destabilizing N-terminal residues Arg, Lys, His, Leu, Phe, Tyr, Trp and Ile. In contrast, the N-terminal Asn, Gln, Asp, and Glu residues (as well as Cys, under some metabolic conditions) are destabilizing owing to their preliminary enzymatic modifications. These modifications include the Nt-deamidation of N-terminal Asn and Gln by the Ntan1 and Ntaq1 Nt-amidases, respectively, and the Nt-arginylation of N-terminal Asp and Glu by the Ate1 R-transferase, which can also Nt-arginylate oxidized Cys, either Cys-sulfinate or Cys-sulfonate. They can form in animal and plant cells through oxidation of Cys by nitric oxide (NO) and oxygen, and also by N-terminal Cys-oxidases (19, 44, 52, 59, 61, 91-93). In addition to its type-1 and type-2 binding sites that recognize, respectively, the basic and bulky hydrophobic unacetylated N-terminal residues, an N-recognin such as Ubr1 contains other substrate-binding sites as well. These sites recognize substrates that are targeted through their internal (non-N-terminal) degrons, as indicated on the diagram (12). Hemin (Fe3+-heme) binds to the Ate1 R-transferase, inhibits its Nt-arginylation activity and accelerates its in vivo degradation. Hemin also binds to Ubr1 (and apparently to other N-recognins as well) and alters its functional properties, in ways that remain to be understood (43). As shown in the diagram, the unacetylated Met of the N-terminal MΦ motif is recognized by both yeast and mammalian Ubr1; this capability greatly expands the substrate range of the Arg/N-end rule pathway (16).

Fig. S2. Specificities and subunit compositions of Nα-terminal acetylases (Nt-acetylases).

(A) Substrate specificities of S. cerevisiae Nt-acetylases. “Ac” denotes the Nα-terminal acetyl moiety. The bulk of Nt-acetylases are associated with ribosomes (94, 95). The specificities of mammalian Nt-acetylases are similar to those of their yeast counterparts, but an individual mammalian genome encodes more than ten Nt-acetylases, in contrast to four in S. cerevisiae. Some mammalian Nt-acetylases, such as NatF (its catalytic subunit is called Naa60 (see fig. S4H, I)) (22), can Nt-acetylate N-terminal motifs that include Met-Lys or Met-Arg, which are rarely if ever Nt-acetylated in S. cerevisiae. This compilation of Nt-acetylases and their specificities is derived from data in the literature ((21, 89, 90, 96-108) and references therein).

(B) Subunits of S. cerevisiae Nt-acetylases. This paper employs the revised nomenclature for subunits of Nt-acetylases (109) and cites older names of these subunits in parentheses.

Fig. S3. The targeting of MX-Rgs2 proteins by the yeast and human Ac/N-end rule and Arg/N-end rule pathways.

(A) CHX chases with the hypertension-associated mutant human ML-Rgs2ha in wild-type, naa30Δ, ubr1Δ, and naa30Δ ubr1Δ S. cerevisiae.

(B) As in A but in human HeLa cells with wild-type human MQ-Rgs2ha and hypertension-associated mutants MR-Rgs2ha and ML-Rgs2ha.

(C) HeLa cells expressing MQ-Rgs2ha or PQ-Rgs2ha together with Teb43f were treated with a cell-penetrating crosslinker, followed by immunoprecipitations with anti-flag, reversal of crosslinks, SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting with anti-ha and anti-flag (see also Fig. 2H and Materials and Methods). Note the coimmunoprecipitation of MQ-Rgs2ha with Teb43f, and the absence of coimmunoprecipitation of PQ-Rgs2ha.

(D) Quantification of data in A. 100% corresponded to the zero-time level of ML-Rgs2ha in naa30Δ ubr1Δ S. cerevisiae.

(E) Quantification of data in B. 100% corresponded to the zero time level of PQ-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells.

In every set of degradation curves shown in this figure and in the main Figs. 1 and 3, 100% at zero time was chosen to correspond to the relative initial level of the most slowly degraded test protein in a given set. Panel A (quantified in D) and panel B (quantified in E) show the results of CHX-chases that were independently carried out counterparts of CHX-chases that are shown in the main Fig. 1B (quantified in D) and 1F (quantified in E), respectively. These comparisons illustrate qualitative reproducibility of independently generated data (particularly the robustly reproduced order of metabolic stabilities of specific test proteins in specific genetic backgrounds), which differed in relatively minor aspects of corresponding degradation curves. In our extensive experience with repeated CHX-chases and 35S-pulse-chases in either S. cerevisiae or HeLa cells, a strictly quantitative reproducibility of independently produced and measured chase-degradation patterns remains the aim to be reached.

(F) Extracts from HeLa cells expressing MQ-Rgs2ha in the presence or absence of coexpressed Teb43f or and in the presence of the MG132 proteasome inhibitor, as indicated. MQ-Rgs2ha was immunoprecipitated from extracts using anti-ha antibody, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody to detect polyubiquitin chains linked to MQ-Rgs2, and with anti-flag, anti-ha and anti-tubulin antibodies as well, as shown.

Fig. S4. Degradation assays with MX-Rgs2 proteins in HeLa cells subjected to RNAi of specific Nt-acetylases and Teb4.

(A) CHX-chases with endogenous (not overexpressed) MQ-Rgs2 in HeLa cells subjected to RNAi-mediated knockdowns of endogenous Teb4 or Naa20 (NatB).

(B) Same as in A but CHX-chases with transiently expressed (exogenous) MQ-Rgs2ha.

(C) Relative steady-state levels of exogenous wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha and its MR-Rgs2ha and ML-Rgs2ha mutants in HeLa cells transfected with equal amounts of MX-Rgs2ha plasmids.

(D) ML-Rgs2ha expressed in HeLa cells in the presence of the coexpressed wild-type Teb43f or . Note a strong decrease of ML-Rgs2ha in the presence of wild-type Teb43f but not in the presence of its inactive missense mutant . Note also a much lower steady-state level of active Teb43f (in comparison to the inactive ), owing to the previously described self-targeting of active Teb4 for degradation (24).

(E) Same as in D but with MR-Rgs2ha.

(F) Quantification of data in C (relative levels of the three MX-Rgs2ha proteins).

(G) Same as in F but quantification, using qRT-PCR, of the relative levels of mRNAs encoding the three MX-Rgs2ha proteins. Standard errors of means (SEMs), with qRT-PCR assays in triplicate for each sample, are indicated as well.

(H) Steady-state levels of transiently expressed (exogenous) MR-Rgs2ha in HeLa cells subjected to RNAi-mediated knockdowns of either endogenous Naa60, the cognate (for MR-Rgs2ha) NatF Nt-acetylase, or endogenous Naa20, the non-cognate (for MR-Rgs2ha) NatB Nt-acetylase. Note the increase in MR-Rgs2ha in response to RNAi of Naa60 but not of Naa20.

(I) Same as in H but with MK-Rgs2ha, a derivative of wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha not encountered, thus far, among human patients, that contained another basic residue at position 2.

(J) 35S-pulse-chases with MX-Rgs2ha (X=R, Q, L) in HeLa cells.

Fig. S5. Mass spectrometric analyses of Nt-acetylation of MQ-Rgs2 and MQ-Rgs21-10-[GST]. (A) Wild-type MQ-Rgs2ha purified from human HEK293 cells is Nt-acetylated. (B) Non-Nt-acetylated (upper panel) and Nt-acetylated MQ-Rgs21-10-[GST] fusion (lower panel) purified from E. coli that either lacked or expressed, respectively, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe NatB Nt-acetylase (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. S6. Rgs2, Teb4, N-terminal acetylation, and the N-end rule pathway. Rgs2 and Teb4 are, respectively, a substrate and Ac/N-recognin of the mammalian Ac/N-end pathway. Only some Rgs2-regulated processes (including the Gαq-mediated activation of Erk1/2 kinase) are shown. Both wild-type MQ-Rgs2 and its hypertension-associated mutant MR-Rgs2 (the latter is not shown) are Nt-acetylated and conditionally destroyed by the Teb4-mediated Ac/N-end rule pathway. In contrast, another hypertension-associated mutant, ML-Rgs2, is targeted by both the Ac/N-end rule pathway and the Arg/N-end rule pathway (see the main text) (fig. S1C, D). Some abbreviations: IP3, inositol trisphosphate. DAG, diacyglycerol.

Fig. S7. Mammalian RGS proteins as identified or predicted N-end rule substrates.

Human RGS proteins as identified or possible (predicted) substrates of either the Ac/N-end rule pathway, or the Arg/N-end rule pathway, or both pathways at the same time, depending on the Nt-acetylation status of a specific RGS protein. See also the main text.

Table S1. S. cerevisiae strains used in this study.

Table S2. Plasmids used in this study.

Table S3. Some PCR primers used in this study.