Abstract

Objective

To explore a possibility of single-cell analysis of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.

Methods

Two hundred and twenty cells were isolated by laser-capture microdissection from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded cervical tissue blocks from 8 women who had HPV DNA detected in their cervical swab samples. The number of type-specific HPV copies in individual cells was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction with and without a prior reverse transcription. Cells were assayed and counted for more than once if the corresponding swab sample was positive for ≥2 HPV types.

Results

Infection with HPV16, HPV39, HPV51, HPV52, HPV58, HPV59, and HPV73 was detected in 12 (5.5%) of 220, 3 (9.4%) of 32, 3 (5.8%) of 52, 11 (22.9%) of 48, 9 (18.8%) of 48, 3 (9.4%) of 32 and none of 20 cells, respectively. Numbers of HPV genome copies varied widely from cell to cell. Coexistence of multiple HPV types was detected in 6 (31.6%) of 19 positive cells from one of the 6 women who had 2 or 3 HPV types detected in their swab samples.

Conclusion

Given the heterogeneity of HPV status in individual cells, further clarification of HPV infection at the single-cell level may refine our understanding of HPV-related carcinogenesis.

Keywords: Human Papillomavirus, Laser-Capture Microdissection, Single Cell

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a causative agent of cervical cancer and its precursor, high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) [1-6]. The virus belongs to the Papillomaviridae family with more than 170 types having been fully characterized to date [7]. Genital infections with multiple HPV types are common, particularly among young women and women with cytological abnormalities [8-10]. It remains largely undermined whether different HPV types can concurrently exist in the same cell in the natural history of the infection although such a possibility has ever been suggested by a study showing coexistence of two HPV types within the same primary keratinocyte in vitro [11] and a case report of double infection with HPV1 and HPV63 within the same nucleus [12]. Considering that formation of neoplasia usually initiates from a single cell, mediated through clonal expansions [13-15], clarification of coinfection with multiple HPV types at the single-cell level would refine our understanding of the inter-type interaction and its association with carcinogenesis of the infection.

In the past two decades, considerable efforts have been made to investigate clinical relevance of HPV DNA loads which were usually measured on cervical swab samples. The reported viral loads vary widely, ranging from a few to millions of copies per unit of cellular DNA [16-19]. These values reflect both numbers of positive cells and copies of HPV genomes in individual cells, as swabbing collects a mixture of exfoliated cells. The consequences may not be the same for infections with a large number of positive cells but few copies of viral genomes in each as compared to those with a small number of positive cells but many copies of viral genomes in each, although the overall viral loads could be similar. To better understand how the levels of HPV loads play a role in the development of cervical lesion, an approach for measuring viral loads at the single-cell level is desirable.

This study sought to explore the possibility of single-cell analysis of HPV infections using laser-capture microdissection (LCM) followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) with and without a prior reverse transcription (RT).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens

Archived formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cervical tissue blocks from 8 women were retrieved from the University of Washington Biorepository. These women were participants of the Evaluation of Cervical Cancer Screening Methods (ECCSM), the study that was designed to evaluate screening strategies for identifying women with high-grade CIN. Women in the ECCSM underwent a routine pelvic examination and provided cervical samples for thin-layer Pap and HPV testing. Those with oncogenic HPV types detected in a cervical sample or a screening Pap indicating the presence of abnormal cytology were asked to return for colposcopy and biopsy. DNAs for HPV testing were isolated from cervical swab samples using the QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD) and assayed by PCR-based reverse-line blot [20]. All 8 women had HPV16 DNA detected in their cervical swab samples; 6 of them were concurrently positive for other HPV types, including HPV39, HPV51, HPV52, HPV58, HPV59 and/or HPV73. A detailed description of the design and population of the ECCSM study was presented elsewhere [21]. Use of specimens for the present study has been approved by the Institute Review Board of University of Washington.

CaSki cell line was used to assess degrees of DNA recovery by single-cell analysis. As reported previously by others [22,23], there are about 500-600 integrated HPV16 genome copies per cell, estimated by Southern blot analysis of CaSki cellular DNA with HPV16 probe. This cell line, initially obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), has been routinely maintained in our laboratory. Cells were cultured and harvested at ~85% confluence, fixed with formaldehyde, pelleted and paraffin-embedded for sectioning as other FFPE samples.

Isolation of single cells by laser-capture microdissection

Serial 5-μm sections were cut from FFPE cervical tissue blocks and mounted on polyethylene naphthalate membrane-coated slides (Leica Bio-systems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining was used to guide microdissection. Slides were incubated at 60°C for 30 minutes in a drying oven. Tissue sections were deparaffinized in 2 changes of xylene for 30 seconds each, followed by rehydrated in a series of graded ethanol to deionized water, then counterstained using HistoGene Staining Solution (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA). Finally, the tissues were dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and dried at room temperature for 10 minutes.

LCM was performed on a Leica's LMD6000 platform, a non-contact system using a 355 nm UV laser beam. Cells were identified morphologically; margins of the cells were microscopically circumscribed with a digital pen. The selected cells were dissected with the laser beam. Figure 1 exemplifies photomicrographs (100X) of a section before and after removal of a single cell. The microdissected cell was transferred into a 0.2 ml PCR tube containing 20 μl proteinase K buffer (1mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris, 0.5% Tween-20, 0.2 mg/ml proteinase K and 10 ng/ml carrier RNA). Cells in individual tubes were incubated in a thermo cycler at 55°C for 8 hours for digestion and then at 95°C for 10 minutes for inactivation of proteinase K. Following that, samples were transferred into 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes, dried with a Vacufuge™ (Ependorf, Hauppauge, NY), re-suspended in 5 μl distilled water, and stored at −20°C until further assay.

Figure 1.

Laser-capture microdissection of cells from a cervical tissue section Arrows indicate a position of a singe cell before (a) and after (b) its removal (100×magnification).

To minimize a potential of sample-to-sample carryover, all instruments for tissue sectioning (such as microtome, tweezer, and slide warmer) were thoroughly cleaned with isopropyl alcohol pads and DNA Away (Molecular Bio Products, San Diego, CA) after the completion of each block. In addition, we kept a space of ~30-50μm between selected cells to minimize a potential of cell-to-cell carryover.

Detection of the HPV genomes by quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Levels of type-specific HPV DNA/RNA and DNA alone in individual cells were measured by qPCR with and without a prior RT, respectively. Types chosen for testing were based on what detected in the corresponding cervical swab sample. Cells were assayed and counted for more than once if the corresponding swab sample was positive for 2 or more HPV types. For example, if a woman had HPV16 and HPV31 detected in her cervical swab sample, cells dissected from this woman's tissue block would be tested for both types; if her swab sample was positive for HPV16 alone, cells from this woman would be tested only for HPV16.

An aliquot of 2 μl sample (equivalent to ~2/5 of a cell) was subjected to reverse transcription in a reaction volume of 3 μl using SuperScript® VILO™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The mixture was incubated at 25°C for 10 minutes and 42°C for 60 minutes followed by 85°C for 5 minutes for inactivation of the reverse transcriptase. DNAs were not removed from RT samples because this procedure was used to maximize a sensitivity of the detection rather than quantify the amount of HPV transcripts. SiHa RNA (9 ng/μl) and sterile water were included in each run of the RT as a positive and negative control, respectively. A success of the RT was indicated by the positive control which tested positive for HPV16 by qPCR with RT (mean, 255,181 copies; SD, ±13,922) but negative by qPCR without RT.

The qPCR assay was set up in a reaction volume of 10 μl with TaqMan Universal PCR Master Kit (Applied Bio-systems, Foster City, CA), 0.09 μM of primers, 0.06 μM of probe, and 1μl sample (equivalent to 1/5 of a cell for sample without a prior RT or to 1/7.5 of a cell (1/3*2/5) for sample with a prior RT). The sequences of the primers and probes for 7 HPV types (i.e., HPV types 16, 39, 51, 52, 58, 59 and 73) are listed in table 1. The specificity of each set of primers and probe was previously verified by testing with plasmids containing DNAs of other HPV types at a concentration of 105copies/μl [19]. PCR amplification was carried out on an Applied Bio-systems 7900 HT Sequence Detection System with a cycling program of holding at 50°C for 2 minutes and then at 95°C for 10 minutes followed by a two-step cycle of 10 seconds at 95°C and 1 minute at 60°C for 40 cycles. A log-phase 6-point standard curve (ranging from 106 to 101 copies) for each type of HPV was implemented in each set of the assay. We manually checked and confirmed amplification curves for all positive tests. The numbers of HPV copies were determined by linear extrapolation of the cycle threshold values using the equation derived from the standard curve. The observed values were converted to copy number per cell by multiplying 7.5 and 5 for those obtained by RT-qPCR and qPCR without RT, respectively.

Table 1.

Primers and probes for qPCR

| HPV types | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Probe (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | TTCGGTTGTGCGTACAAAGC | VIC-CACACGTAGACATTCGT-MGB | GCCCATTAACAGGTCTTCCAAA |

| 39 | TGACCTTGTATGTCACGAGCAAT | VIC-AGGAGAGTCAGAGGATG-MGB | TGCATGGTCGGGTTCATCTA |

| 51 | GCTCCGTGTTGCAGGTGTT | VIC-AAGTGTAGTACAACTGGC-MGB | GGGTGTCTCCACTGCTTTCC |

| 52 | GACAGCTCAGATGAGGAGGATACA | VIC-ATGGTGTGGACCGGC-MGB | TGGCTTGTTCTGCTTGTCCAT |

| 58 | GACAGCTCAGACGAGGATGAAA | VIC-AGGCTTGGACGGGC-MGB | TGGCCGGTTGTGCTTGT |

| 59 | TGACTCCGACTCCGAGAATGA | VIC-AAAGATGAACCAGATGGAGT-MGB | TCGTCTAGCTAGTAGCAAAGGATGAT |

| 73 | ACCAACAACCGAAATTGACCTT | VIC-CATGTTACGAGTCATTGGA-MGB | CTGTTTCATCCTCATCCTCTGAGTT |

Verification of multiple HPV types in single cells by DNA sequencing

Cells positive for more than one type of HPV by qPCR were further assayed by PCR-based DNA sequencing to verify the presence of multiple types. Briefly, a regular PCR in a reaction volume of 25 μl was performed with 1μl of qPCR products as sample input. The PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis and visualized on an ethidium bromide-stained 1.5% agarose gel. The PCR-generated DNA fragments were cloned into pSC-B plasmid using a StrataClone Ultra Blunt PCR Cloning Kit according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The accuracy of the target inserts was confirmed by DNA sequencing from both directions with a pair of M13 primers (forward: 5’-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT; reverse: 5’-AACAGCTATGACCATG).

Statistical analyses

A McNemar test with continuity correction was used to compare frequencies of positive detections by qPCR with versus without a prior RT assay. A difference in log10-transformed viral copy numbers measured by qPCR with, compared to without, a prior RT was assessed by a Student's t-test. Fisher's exact test was used to examine frequencies of coexistent HPV types in single cells. Statistical tests were at the 5% two-sided significance level.

RESULTS

Recovery of the HPV16 genomes from microdissected CaSki cells

We pooled 20 dissected CaSki cells together to get an expected total of ~10,000 HPV16 genome copies. The pooled sample was diluted to a series of 3 concentrations (i.e., 500, 100, and 10 HPV16 genome copies/μl) and assayed by qPCR without RT. The number of HPV16 copies detected was 66.4 for a sample input of 500 copies and 21.5 for a sample input of 100 copies, accounting for 13.3% and 21.5% of the expected number, respectively. HPV16 genome for a sample input of 10 copies was undetectable.

Type-specific HPV infections detected at the single-cell level

The number of cells dissected from FFPE cervical tissue blocks ranged from 16 to 48 per woman with a total of 220 obtained from 8 women (4 with a histologic diagnosis of CIN2 and 4 with CIN1). The LCM was repeated on different tissue blocks for 3 women to increase number of cells (case no. 147 and 427, with an initial collection of 12 cells and a recollection of 20 for each) or to confirm presence of multiple HPV types in single cells (case no. 249, with an initial collection of 12 cells and a recollection of 8 and then 28).

Overall, infection with HPV types 16, 39, 51, 52, 58, 59 and 73 was detected in 12 (5.5%) of 220, 3 (9.4%) of 32, 3 (5.8%) of 52, 11 (22.9%) of 48, 9 (18.8%) of 48, 3 (9.4%) of 32, and none of 20 cells, respectively (18 positive by RT-qPCR alone, 10 by qPCR without RT alone, and 13 by both). The proportions of positive detections were comparable between the procedures with and without RT (Table 2, 6.9% versus 5.1%, P = 0.19).

Table 2.

Type-specific HPV infections detected in individual cells by qPCR with and without a prior reverse transcription

| Case no. | Histologic diagnosis | Types detected in swab sample | No. of cells | No. of tests | No. (%) of type-specific

positive cells by qPCR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| without RT | with RT | either† | |||||

| 42 | CIN2 | HPV16 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 147 | CIN2 | HPV16 | 32# | 32 | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (6.3) |

| HPV39 | 32 | 0 | 3 (9.4) | 3 (9.4) | |||

| 249 | CIN1 | HPV16 | 48* | 48 | 3 (6.3) | 5 (10.4) | 6 (12.5) |

| HPV52 | 48 | 9 (18.8) | 8 (16.7) | 11 (22.9) | |||

| HPV58 | 48 | 5 (10.4) | 4 (8.3) | 9 (18.8) | |||

| 427 | CIN1 | HPV16 | 32# | 32 | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) |

| HPV59 | 32 | 1 (3.1) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (9.4) | |||

| 735 | CIN1 | HPV16 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| HPV51 | 20 | 2 (10.0) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (10.0) | |||

| 842 | CIN2 | HPV16 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| HPV73 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 891 | CIN2 | HPV16 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1055 | CIN1 | HPV16 | 32 | 32 | 0 | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) |

| HPV51 | 32 | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.1) | |||

| Total | 220 | 452 | 23 (5.1) | 31 (6.9) | 41 (9.1) | ||

including 12 cells initially collected, 8 by the 1st repeat and 28 by the 2nd repeat

including 12 cells initially collected and 20 recollected

positive by qPCR with and/or without RT. If positive by both, only one was counted.

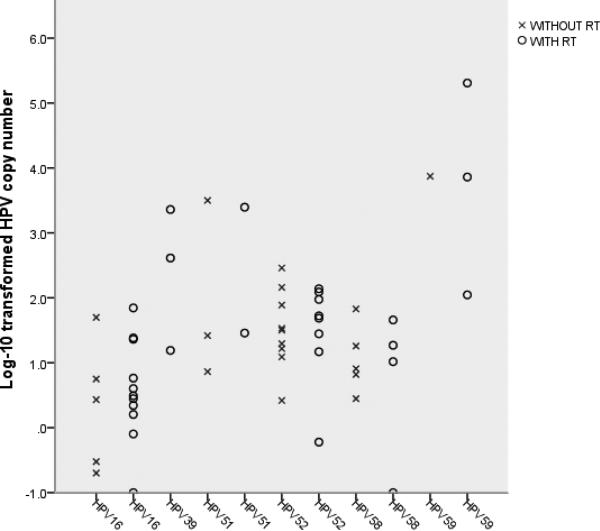

The log10-transformed HPV copy number in individual cells is plotted in Figure 2. The majority of detectable infections were at a level of <2 logs. The mean (SD) of the log10-transformed HPV copy number was 1.22 (±1.27) for cells positive by RT-qPCR alone and 0.91 (±0.73) for those positive by qPCR without RT alone. For cells positive by both, the mean (SD) was 1.73 (±1.45) and 1.68 (±1.16) detected by qPCR with and without a prior RT, respectively. There were no appreciable differences in type-specific copy numbers by qPCR with versus without RT for all types (p = 0.79) except for HPV59 (case no. 427). Of 32 cells tested for HPV59, 2 were negative by qPCR without RT but positive by RT-qPCR at a level of 2.05 and 3.86 logs, respectively; one was positive by both but with a substantially greater number of copies detected by qPCR with, compared to without, RT (5.31 versus 3.87 logs).

Figure 2.

Log10-transformed type-specific HPV copy number in individual positive cells The mean (SD) of log10-transformed copy number detected by qPCR with and without a prior reverse transcription was 1.44 (±1.35) and 1.35 (±1.05), respectively (p = 0.79).

Coexistence of multiple HPV types in single cells

Six women had 2 or 3 HPV types detected in their cervical swab samples. By analysis of the corresponding types of HPV in individual cells, presence of more than one type of HPV in single cells was found in one woman (Table 3, case no. 249). In the initial analysis of 12 cells, 3 were positive for HPV16 and/or HPV52 with coexistence of both types detected in 2. We repeated LCM on different FFPE blocks from this woman twice with another 36 cells collected. Infection with more than one type of HPV was detected in 3 (one with HPV16 and HPV52, one with HPV52 and HPV58, and another with all 3 types) in the first repeat of 8 cells and coexistence of HPV52 and HPV58 in one in the second repeat of 28 cells.

Table 3.

Multiple HPV types detected in single cells from a woman (case no. 249) who had HPV16, HPV52 and HPV58 detected in her cervical swab sample

| Test | No. of cells | No. of HPV-positive cells | Identification numbers for cells positive for multiple types | No. of viral copies in single

cells |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV16 | HPV52 | HPV58 | ||||

| Initial test | 12 | 3 | 2 | 0.3 | 16.5 | |

| 12 | 0.2 | 26.2 | ||||

| 1st repeat | 8 | 5 | 5 | 45.7 | 34.2 | |

| 8 | 4.0 | 14.8 | ||||

| 3 | 5.8 | 94.5 | 6.6 | |||

| 2nd repeat | 28 | 11 | 24 | 31.8 | 8.1 | |

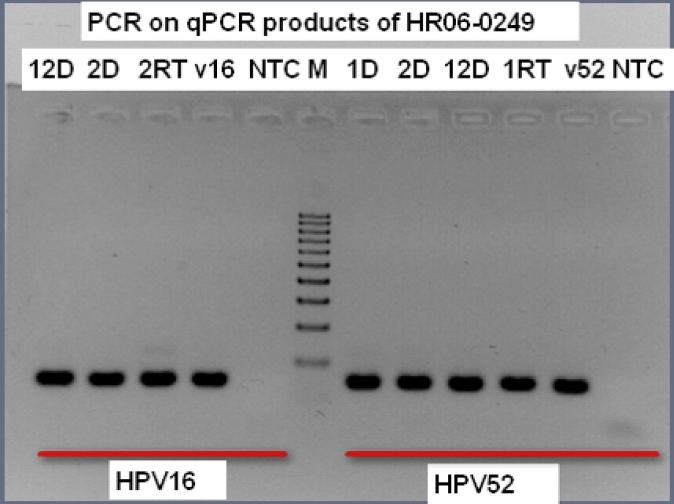

Figure 3 shows an example of re-amplification of qPCR products of 3 positive cells from the initial test of case no. 249 including 2 (#2 and #12) each positive for HPV16 and HPV52 and one (#1) positive for HPV52. The PCR products were cloned into pSC-B vector; sequences of the target region (66 bps for HPV16 and 64 bps for HPV52) were confirmed by sequencing with M13 primer (data not shown). The confirmatory analysis (i.e., re-amplification of qPCR products) was performed on all cells from the repeated test showing multiple HPV types in each and a set of cells tested negative by qPCR. All of the positive tests were confirmed; none of the negative cells displayed any visible bands (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Re-amplification of HPV16 and HPV52 with an aliquot of qPCR products as sample input, visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel Three positive cells were indentified by the initial qPCR analysis of 12 cells from case no. 249. One (cell number 1) was positive for HPV52; two (cell number 2 and 12) were positive for both HPV16 and HPV52. RT = products from qPCR with RT; D = products from qPCR without RT; v16 = HPV16-positive control; v52 = HPV52-positive control; NTC = negative control; M = maker (100-bp DNA ladder).

Of the remaining 5 women with 2 HPV types detected in their cervical swab samples; 4 (case no. 147, 427, 735, and 1055) had both types detected by qPCR, but in different cells (Table 2). None of 14 positive cells from these 4 women, in contrast to 6 (31.6%) of 19 positive cells from case no. 249 displayed multiple types of HPV within the single cell (P = 0.03).

DISCUSSION

In this proof-of-principle study, we demonstrated the feasibility of single-cell analysis of HPV infection by LCM followed by qPCR. Although use of LCM for analyses of HPV status was reported before [24-26], previous studies focused on infections in individual lesions or individual components of the lesions. Data from this study revealed the heterogeneity of HPV status in individual cells showing that most cells dissected from tissue blocks from women with HPV DNA detected in their cervical swab samples did not have a detectable HPV infection; in a small set of HPV-positive cells, numbers of viral copies varied substantially from cell to cell.

Considering the depth of tissue sections and potential loss in sample extraction, we expected that DNAs retrieved from single cells might represent only a fraction of the tissue's entire content. Thus, we used CaSki cells to assess degrees of recovery. The lower than the expected number of HPV16 copies observed from CaSki cells suggests that the actual number of viral copies in cells from clinical samples might be larger than what we observed. This may in part explain why the type-specific infection was detected only in a small fraction of cells. We chose not to adjust for number of viral copies according to percentages of the recovery. This is because the assay-related DNA loss may vary from cell to cell; ratios of the observed to expected copies may not necessarily be linear. Nevertheless, data from the present study clearly indicated that the number of viral copies in individual positive cells was not a unique value but a distribution of values. One interpretation for the broad range of viral copies pertains to cellular differentiation and proliferation as HPV utilizes the host cell DNA replication machinery for its own replication. Alternatively (or in addition), cells may differ in numbers of initially acquired HPV copies and/or physical statuses of the viral genomes, thereby resulting in differing accumulation of viral copies.

In this study, viral loads were measured by qPCR with and without a prior RT. It should be pointed out that the copy number detected by RT-qPCR represented both HPV DNA and RNA. We expected that qPCR with, compared to without, a prior RT would identify more infected cells if the virus was transcriptionally active; the observed difference, however, was not substantial. We noted that type-specific infection was not detected in 10 cells by RT-qPCR but was detected by qPCR without RT. This discrepancy could be in part explained by a lack of HPV RNA due to either inactive transcription or RNA degradation and/or a loss of few DNA copies in the RT procedure as the number of HPV copies detected by the latter was quite small. We did not see appreciable differences in HPV copy numbers detected by RT-qPCR versus qPCR without RT for all types except for HPV59. The number of HPV59 copies detected by RT-qPCR was substantially greater than that by qPCR without RT, suggesting an active transcriptional status of the virus. Identification of viral transcription in individual cells is important as detection of HPV RNA as compared to DNA in cervical swab samples has been shown to be more specific for predicting high-grade CIN [27-29].

In agreement with a previous case report of double infection with HPV1 and HPV63 within the same nucleus identified by fluorescence in situ hybridization [12], we repeatedly detected coexistence of two or three HPV types in single cells dissected from different tissue blocks from one woman. Our results cannot be explained by assay-related cross-reaction as the specificity of primers and probes was well verified previously [19]. Also, all sequences of multiple types detected in single cells were confirmed by direct sequencing of PCR products. One concern, however, is whether types detected were from different rather than the same cell. Although cells selected displayed clean margins and there was space (~30-50μm) between the selected cells, a possibility of cell-cell overlap could not be excluded. If one type of HPV is in an upper cell and another type in a cell beneath, our results could be misinterpreted. Arguing against this is the fact that coexistence was repeatedly detected in one woman. Had the overlap been a reason for detection of multiple types, it would have been expected to occur in other 4 women who had both types detected by qPCR. However, none of 14 positive cells from these 4 women as compared to 6 of 19 positive cells from case no. 249 was positive for multiple types. Furthermore, had a detection of multiple HPV types in single cells resulted from cell-to-cell carryover, it would have been more likely detected in women with larger number of viral copies in single cells, such as case no. 427. In fact, our finding of coexistence of multiple HPV types in single cells is in part supported by a study in vitro showing that a subset of high-risk HPV types can be stably maintained in the same cell, interactions between types do occur [11].

Genital infection with multiple HPV types is common, detected in 15-40% of women with CIN of all grades [9,24]. An increased risk of cervical lesions among women infected with multiple types versus only one type of HPV has been observed in some studies [30-34] but not in others [9,35-37]. Previous studies of HPV DNA in microdissected cervical lesions have demonstrated that most lesions contained only one type of HPV; the lesions with two types appeared to morphologically represent the collision of two lesions each with a single type of HPV, suggesting one virus-to-one lesion [24,26]. On the other hand, presence of multiple types of HPV in microdissected cervical lesions has also been reported from a vaccine trial [38]. The finding of coexistent HPV types in single cells is intriguing, as it may bring about a new area in HPV research. It would be interesting to know the frequency, duration, and clinical relevance of multiple HPV types in single cells, whether different types enter into cells concurrently or sequentially, and how they interact with each other. Clearly, additional studies are warranted to examine HPVs in individual cells over a course of the infection, as well as studies to identify mechanisms of type-type interaction and host-virus interaction.

The major limitation of the present study was the limited sample size with only 8 women included. Thus, our results should be interpreted with caution. In addition, the image of individual cells prior to microdissection was not recorded. Consequently, the relationship between HPV status and morphologic features of the cell remained undetermined. Finally, in analyses of HPV16 DNA from dissected CaSki cells, the viral genome was undetectable for a sample with an expected number of 10 copies, suggesting that we might miss infections with few HPV genome copies. It is likely that the actual number of positive cells might be larger than what was observed in the present study.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the feasibility of single-cell analysis of HPV infections. Given the heterogeneity of HPV status in individual cells (in terms of copy number, viral transcription, and coexistence of multiple types), further studies of HPV status at the single-cell level may refine our understanding of HPV-related carcinogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research reported in this publication was supported by National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number CA133569. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Xia Liu was financially supported by a “Plan of Cultivating Future Talents” grant from Shengjing Hospital, China Medical University.

The authors would like to thank the ECCSM investigators for their providing the biological specimens.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional human subjects review board of the University of Washington.

Footnotes

All authors have no commercial or other associations that might pose a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bauer HM, Hildesheim A, Schiffman MH, Glass AG, Rush BB, Scott DR, Cadell DM, Kurman RJ, Manos MM. Determinants of genital human papillomavirus infection in low-risk women in Portland, Oregon. Sex Transm Dis. 1993;20:274–278. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199309000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:244–265. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kjaer SK, van den Brule AJ, Bock JE, Poll PA, Engholm G, Sherman ME, Walboomers JM, Meijer CJ. Human papillomavirus--the most significant risk determinant of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:601–606. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960301)65:5<601::AID-IJC8>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:342–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlecht NF, Kulaga S, Robitaille J, Ferreira S, Santos M, Miyamura RA, Duarte-Franco E, Rohan TE, Ferenczy A, Villa LL, Franco EL. Persistent human papillomavirus infection as a predictor of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Jama. 2001;286:3106–3114. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koshiol J, Lindsay L, Pimenta JM, Poole C, Jenkins D, Smith JS. Persistent human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:123–137. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Villiers EM. Cross-roads in the classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2013;445:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickson EL, Vogel RI, Geller MA, Downs LS., Jr. Cervical cytology and multiple type HPV infection: A study of 8182 women ages 31-65. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:405–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.03.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuschieri KS, Cubie HA, Whitley MW, Seagar AL, Arends MJ, Moore C, Gilkisson G, McGoogan E. Multiple high risk HPV infections are common in cervical neoplasia and young women in a cervical screening population. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:68–72. doi: 10.1136/jcp.57.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rousseau MC, Villa LL, Costa MC, Abrahamowicz M, Rohan TE, Franco E. Occurrence of cervical infection with multiple human papillomavirus types is associated with age and cytologic abnormalities. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:581–587. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Meyers C. Evidence for the coexistence of two genital HPV types within the same host cell in vitro. Virology. 2004;321:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egawa K, Shibasaki Y, de Villiers EM. Double infection with human papillomavirus 1 and human papillomavirus 63 in single cells of a lesion displaying only an human papillomavirus 63-induced cytopathogenic effect. Lab Invest. 1993;69:583–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396:643–649. doi: 10.1038/25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Tine BA, Kappes JC, Banerjee NS, Knops J, Lai L, Steenbergen RD, Meijer CL, Snijders PJ, Chatis P, Broker TR, Moen PT, Jr., Chow LT. Clonal selection for transcriptionally active viral oncogenes during progression to cancer. J Virol. 2004;78:11172–11186. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11172-11186.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao R. From single cell gene-based diagnostics to diagnostic genomics: current applications and future perspectives. Clin Lab Sci. 2005;18:254–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swan DC, Tucker RA, Tortolero-Luna G, Mitchell MF, Wideroff L, Unger ER, Nisenbaum RA, Reeves WC, Icenogle JP. Human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA copy number is dependent on grade of cervical disease and HPV type. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1030–1034. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1030-1034.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marongiu L, Godi A, Parry JV, Beddows S. Human Papillomavirus 16, 18, 31 and 45 viral load, integration and methylation status stratified by cervical disease stage. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:384. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xi LF, Hughes JP, Castle PE, Edelstein ZR, Wang C, Galloway DA, Koutsky LA, Kiviat NB, Schiffman M. Viral load in the natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 infection: a nested case-control study. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1425–1433. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winer RL, Xi LF, Shen Z, Stern JE, Newman L, Feng Q, Hughes JP, Koutsky LA. Viral load and short-term natural history of type-specific oncogenic human papillomavirus infections in a high-risk cohort of midadult women. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1889–1898. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Apple RJ, Wheeler CM. Genotyping of 27 human papillomavirus types by using L1 consensus PCR products by a single-hybridization, reverse line blot detection method. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3020–3027. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3020-3027.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulasingam SL, Hughes JP, Kiviat NB, Mao C, Weiss NS, Kuypers JM, Koutsky LA. Evaluation of human papillomavirus testing in primary screening for cervical abnormalities: comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and frequency of referral. Jama. 2002;288:1749–1757. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker CC, Phelps WC, Lindgren V, Braun MJ, Gonda MA, Howley PM. Structural and transcriptional analysis of human papillomavirus type 16 sequences in cervical carcinoma cell lines. J Virol. 1987;61:962–971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.962-971.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yee C, Krishnan-Hewlett I, Baker CC, Schlegel R, Howley PM. Presence and expression of human papillomavirus sequences in human cervical carcinoma cell lines. Am J Pathol. 1985;119:361–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quint W, Jenkins D, Molijn A, Struijk L, van de Sandt M, Doorbar J, Mols J, Van Hoof C, Hardt K, Struyf F, Colau B. One virus, one lesion--individual components of CIN lesions contain a specific HPV type. J Pathol. 2012;227:62–71. doi: 10.1002/path.3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalantari M, Garcia-Carranca A, Morales-Vazquez CD, Zuna R, Montiel DP, Calleja-Macias IE, Johansson B, Andersson S, Bernard HU. Laser capture microdissection of cervical human papillomavirus infections: copy number of the virus in cancerous and normal tissue and heterogeneous DNA methylation. Virology. 2009;390:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Marel J, Quint WG, Schiffman M, van de Sandt MM, Zuna RE, Dunn ST, Smith K, Mathews CA, Gold MA, Walker J, Wentzensen N. Molecular mapping of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia shows etiological dominance of HPV16. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:E946–953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratnam S, Coutlee F, Fontaine D, Bentley J, Escott N, Ghatage P, Gadag V, Holloway G, Bartellas E, Kum N, Giede C, Lear A. Aptima HPV E6/E7 mRNA test is as sensitive as Hybrid Capture 2 Assay but more specific at detecting cervical precancer and cancer. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:557–564. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02147-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coquillard G, Palao B, Patterson BK. Quantification of intracellular HPV E6/E7 mRNA expression increases the specificity and positive predictive value of cervical cancer screening compared to HPV DNA. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu TY, Xie R, Luo L, Reilly KH, He C, Lin YZ, Chen G, Zheng XW, Zhang LL, Wang HB. Diagnostic validity of human papillomavirus E6/E7 mRNA test in cervical cytological samples. J Virol Methods. 2014;196:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaturvedi AK, Myers L, Hammons AF, Clark RA, Dunlap K, Kissinger PJ, Hagensee ME. Prevalence and clustering patterns of human papillomavirus genotypes in multiple infections. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2439–2445. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrero R, Castle PE, Schiffman M, Bratti MC, Hildesheim A, Morales J, Alfaro M, Sherman ME, Wacholder S, Chen S, Rodriguez AC, Burk RD. Epidemiologic profile of type-specific human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1796–1807. doi: 10.1086/428850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trottier H, Mahmud S, Costa MC, Sobrinho JP, Duarte-Franco E, Rohan TE, Ferenczy A, Villa LL, Franco EL. Human papillomavirus infections with multiple types and risk of cervical neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1274–1280. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bello BD, Spinillo A, Alberizzi P, Cesari S, Gardella B, D'Ambrosio G, Roccio M, Silini EM. Cervical infections by multiple human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes: Prevalence and impact on the risk of precancerous epithelial lesions. J Med Virol. 2009;81:703–712. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li N, Yang L, Zhang K, Zhang Y, Zheng T, Dai M. Multiple Human Papillomavirus Infections among Chinese Women with and without Cervical Abnormalities: A Population-Based Multi-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Front Oncol. 2011;1:38. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2011.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levi JE, Fernandes S, Tateno AF, Motta E, Lima LP, Eluf-Neto J, Pannuti CS. Presence of multiple human papillomavirus types in cervical samples from HIV-infected women. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Dunn T, Zuna RE, Gold MA, Allen RA, Zhang R, Sherman ME, Wacholder S, Walker J, Wang SS. Multiple human papillomavirus genotype infections in cervical cancer progression in the study to understand cervical cancer early endpoints and determinants. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2151–2158. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wentzensen N, Nason M, Schiffman M, Dodd L, Hunt WC, Wheeler CM, New Mexico HPVPRSC No evidence for synergy between human papillomavirus genotypes for the risk of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in a large population-based study. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:855–864. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, Naud P, Salmeron J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter DL, Kitchener HC, Castellsague X, de Carvalho NS, Skinner SR, Harper DM, Hedrick JA, Jaisamrarn U, Limson GA, Dionne M, Quint W, Spiessens B, Peeters P, Struyf F, Wieting SL, Lehtinen MO, Dubin G, group HPs Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2161–2170. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]