Abstract

Compression fracture of the vertebral body is common in the older patients. The possible etiology like osteoporosis or cancer metastasis should be included as a possibility in the differential diagnosis for severe back pain, to prevent delays in diagnosis and treatment. More severe fractures can cause significant pain, leading to inability to perform activities of daily living, and life-threatening in the older patient.

We report a rare case of a 61-year-old man suffering from severe lower back pain and intermittent abdominal fullness. He came to our clinic, where muscle power was normal, but could not stand up or change posture because of severe back pain. Plain film and magnetic resonance imaging of lumbar spine both revealed osteoblastic lesion at L2 spine. Abdomen computed tomography showed a mass at the pancreatic body. The pancreatic cancer with osteoblastic metastasis was diagnosed. After receiving multimodality therapy such as percutaneous vertebroplasty and pain controlling, we provided effective palliation of symptoms, aggressive rehabilitation program, and better quality of life.

Our case highlights the benefits of multidisciplinary cancer treatment for such patient, preventing the complications such as immobilization accompanied with adverse effects like musculoskeletal, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems. All clinicians should be informed of the clinical findings to provide patients with suitable therapies and surveys.

INTRODUCTION

Most people suffered from acute or chronic lower back pain and experienced decreased mobility, stability, and muscle strength.1 The physician shall make the differential diagnosis for it such as vertebral fracture caused by osteoporosis, trauma, metastasis, and idiopathic factors. Fracture due to osteoporosis must conform to low impact trauma and criteria through dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Bone metastasis can be diagnosed through history taking, x-ray, computed tomography (CT), magnetic reonance imaging (MRI), and bone scans. Cancers, such as breast, prostate, kidney, and lung, metastasize to multiple bones including the vertebrae, ribs, and femur.2 In pancreatic cancer, liver and peritoneum metastases are frequent, whereas bone metastases are less common,3,4 which include mostly osteolytic and extremely rare osteoblastic lesions.5

In this study, we reported a patient who suffered from severe back pain. The lumbar x-ray of the patient showed a vertebral compression fracture with an osteoblastic lesion, and pancreatic cancer with bone metastasis was diagnosed. After receiving percutaneous vertebroplasty and controlling the pain, we introduced the patient to an aggressive rehabilitation program and instructed the patient to perform better daily activities.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 61-year-old man had been experiencing severe low back pain, and intermittent abdominal fullness developed 3 months before the admission. The pain sensation with dullness in quality was located over the sacroiliac area. The pain exacerbated particularly at night and radiated to the bilateral scapula. The patient visited the clinic several times, and chronic muscle strain was suspected because no trauma or specific medical history was mentioned. The pain sensation became more severe even under medicine and was accompanied with dysuria, voiding frequency, and poor defecation, thereby prompting the patient to visit our outpatient clinic 1 month before the admission.

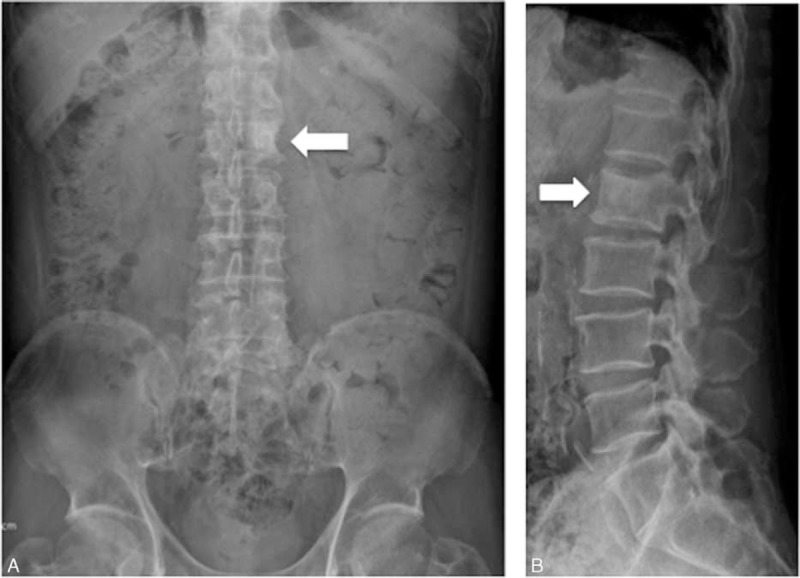

At that time, muscle power in all 4 limbs was normal, but the patient could not stand up or change posture because of severe back pain. The pain occurred spontaneously or by movement. The initial physical examination showed a positive finding in right straight leg raising test (20 degrees) and a negative finding in bilateral Patrick test. The pain became severe while coughing and doing lumbar flexion with radiating numbness and pain to the right thigh and leg. The lateral view of x-ray showed a vertebral compression fracture with an osteoblastic lesion at the L2 vertebral body (Figure 1). Two weeks before admission, the patient underwent MRI of the lumbar spine, which revealed osteoblastic metastasis with heterogeneous enhancement in the L2 vertebra, direct tumor invasion of left paraspinal soft tissue, and psoas muscle myositis (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Anterior-posterior (A) and lateral view (B) of x-rays showing a hyperdensity lesion at the L2 level, with mild wedge shape at the T12 to L1 vertebral body.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Axial T2-weighted images showing an abnormal lesion in the left side of the L2 vertebral body. (B) Axial T1-weighted image obtained after intravenous administration of gadolinium showing heterogeneous enhancement. Metastases of vertebral body, direct tumor invasion of soft tissue, and left psoas muscle myositis are noted.

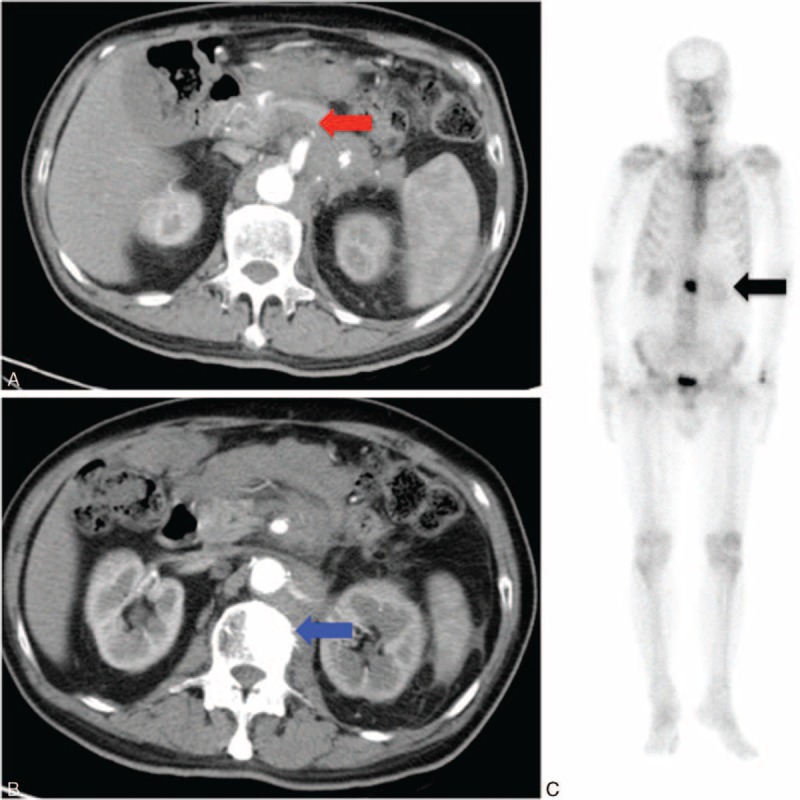

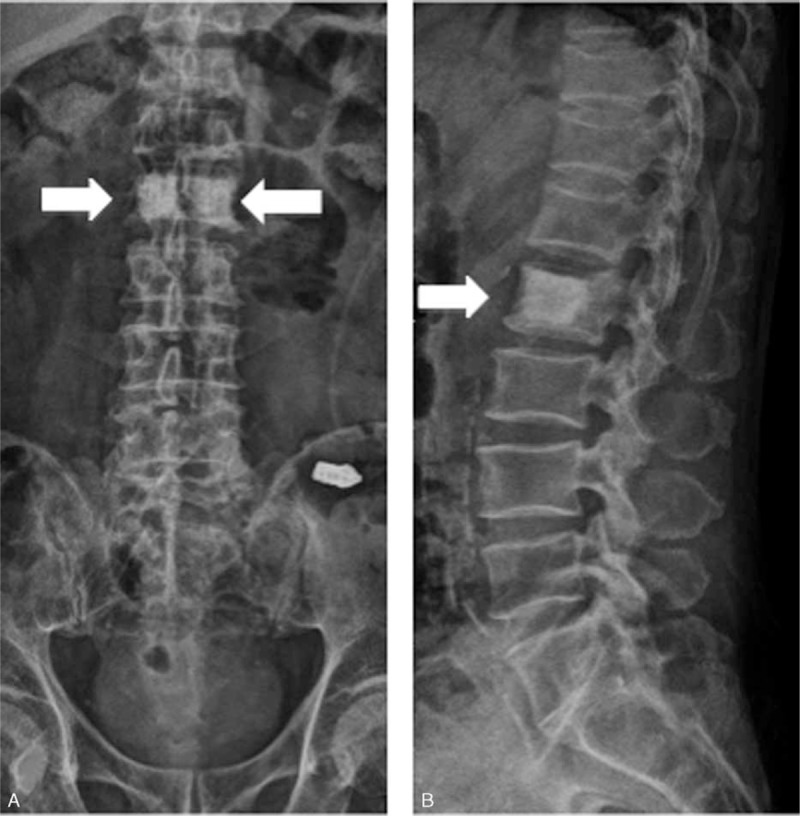

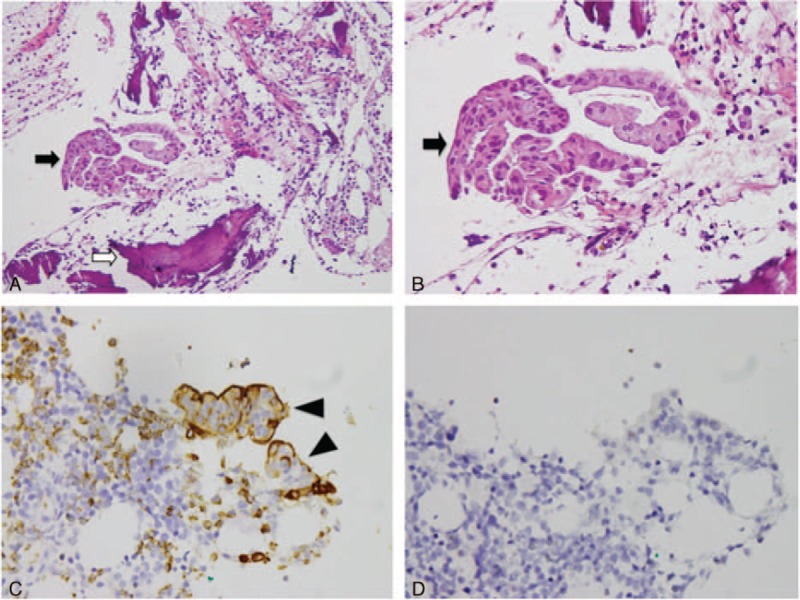

One day before the admission, severe back pain was exacerbated with abdominal fullness and cold sweating. Thus, the patient came to our emergency room. Abdominal sonography showed multiple masses over the liver. Severe back pain lasted throughout the day with a visual analog pain score (VAS) described as 9 to 10 even under treatment with Ultracet (tramadol 37.5 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg) thrice per day, but quit because he could not tolerate the side effect such as nausea, vomiting, and general weakness after medication. Under the impression of osteoblastic metastasis in the L2 vertebra with direct tumor invasion of left paraspinal soft tissue, and psoas muscle myositis, the patient was admitted. During admission, the laboratory data, such as complete blood count, electrolyte, liver function, and renal function, were within the normal range. The tumor markers of alpha-fetaprotein, prostatic-specific antigen, and carbohydrate antigen-199 were also within the normal range. However, carcinoembryonic antigen (454.63 ng/mL, normal range <5.0 ng/mL) and carbohydrate antigen-125 (2412.9 U/mL, normal range <35 U/mL) were elevated. Abdomen CT (Figure 3A) was arranged and showed a 60.8 mm × 16.5 mm ill-defined mass at the pancreatic body, with encasement of the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery and aorta, and multiple liver and L2 vertebral metastasis (Figure 3B). Enlarged or confluent lymph nodes were noted at the paraaortic region, paracaval region, and right subphrenic region. Metastatic lymphadenopathy was highly suspected. The technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate whole-body bone scan showed abnormal increased uptake at the L2 level (Figure 3C). Percutaneous vertebroplasty with injection of 5 mL bone cement and L2 vertebral body biopsy were performed under guidance of radiology 3 days after the admission (Figure 4), and metastatic adenocarcinoma (cT4N1M1) was diagnosed (Figure 5).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Abdominal CT with contrast showing an ill-defined mass in the pancreatic body. Tumor involves the celiac axis and the superior mesenteric artery, with some enlarged lymph nodes at the paraaortic region (red arrow); (B) the CT showed a hyperdensity lesion at L2 vertebral body (blue arrow); and (C) the bone scan shows abnormal uptaking in about the L2 level (black arrow). Bone metastasis was suspected. CT = computed tomography.

FIGURE 4.

Anterior-posterior (A) and lateral view (B) of x-rays showing 2 hyperdensity regions at the L2 level after percutaneous vertebroplasty.

FIGURE 5.

Histologic findings of metastatic adenocarcinoma at L2 vertebral body. (A) and (B) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (A: 10 × 20, B: 10 × 40): metastatic adenocarcinoma, composed of tumor cells (black arrow) with large, pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, arranged in tubular or small glandular structure. Bone (white arrow); (C) immunohistochemical stain shows positive to carcinoembryonic antigen (arrow head) (10 × 40); (D) immunohistochemical stain shows negative to thyroid transcription factor-1 (10 × 40).

After receiving percutaneous vertebroplasty, the severe back pain subsided with VAS about 3 to 4, and the patient could walk without any device under the same medicine prescribed before for pain control. The performance status under Karnofsky and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scales were improved from 20 to 80 and 4 to 1. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment for the pancreatic cancer was added into the treatment, but the course of treatment was halted because the patient could not tolerate the side effect. Currently, the patient is on best supportive care and palliative treatment, and the quality of life and activity of daily living were the same as the time after this procedure, which was performed for >1 year.

DISCUSSION

Etiologies of lower back pain are variable, and vertebral fracture can be diagnosed through history taking and image data. The diagnosis of osteoporosis in which bone marrow density decrease and bone lucency can also be noted by the image. In addition, the fracture caused by metastasis with heterogenic lesion and irregular borderline should be considered. Normal bone development and maintenance are sustained through a balanced communication between osteoclasts and osteoblasts.6 Bone metastases usually exhibit disturbances of both cell types and are a public health problem because of the increasing incidence of cancer at 3.2 million per year.7 Yin et al8 noted that breast and lung cancers are the most frequent causes of osteolytic bone lesions. Previous literature reviews showed that bone metastases in pancreatic cancer are mostly osteolytic and are extremely rare osteoblastic lesions,5 which are usually induced by prostate cancer.9 In our case, we also surveyed for prostate cancer. However, data were all within the normal range. Pancreatic cancer was determined through sonography and CT image.

Joffe and Antonioli mentioned that most bone metastases in pancreatic cancer are osteolytic, but osteoblastic bone metastases were commoner than previously recognised.10 Borad et al3 reported in 2009 that the most common sites of skeletal metastases from pancreatic cancer with a predominance of osteoblastic than osteoclastic lesions were in the vertebrae.3 Pneumaticos et al4 also presented a case of pancreatic cancer with severe back pain caused by an osteoblastic lesion at the L3 vertebra. Thus, pancreatic cancer should be considered in cases with osteoblastic vertebral lesions.

Pancreatic cancer, an aggressive malignancy with a very poor prognosis, is the seventh leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide.11 The 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer patients is <5%.12 Traditional chemotherapeutics have largely failed to improve the survival significantly.13 The current standard treatment for patient with advanced pancreatic cancer is gemcitabine monotherapy, with a median survival rate of approximately 9 to 15 months for patients with locally advanced disease and 3 to 6 months for those who present with metastases, respectively.14 In using gemcitabine and novel targeted agents, such as erlotinib, the survival rate is much improved but accompanied with frequent skeletal metastases.3 On the basis of these findings, pain will become the major problem as survival prolongs. Considering the stress-related periosteal tumor development, microfractures, macrofractures, periosteum, and surrounding nerve damages,15 the acute peaks of pain when moving under a painful background is mentioned.

Without suitable treatment, the patient became bedridden and used a wheelchair for ambulation. Muscle weakness was noted because of the immobilization. If the pain is not well managed, fatigue, insomnia, and depression will impede the aggressive rehabilitation. Moreover, joint contractures, muscle atrophy, pressure sores, pneumonia, cardiovascular problems, and decreased functional status can influence daily activities.

The current gold standard treatment for painful bone metastases is radiotherapy and analgesic indication. The pain can be treated with medicine but with significant side effects. Furthermore, the course of treatment is time-consuming for the patient, caregiver, and physician.16 If background pain is poorly controlled, the pain induced by movement requires more medicine and leads to adverse events. Radiotherapy is a good solution but with some limitations, such as no response, delayed effect, and poor tissue tolerance. When a localized painful lesion is identified, surgery is rarely a satisfactory therapeutic option because it is often an extremely invasive option for a fragile patient.

Vertebroplasty, with percutaneous intravertebral injection under radiology guidance, is a minimal invasive local therapy even for spine metastasis and osteoporosis fractures. Clinical vertebroplasty according to Marc et al17 that consistent back pain with VAS of 5 at fracture level is the indication. The risks and complications of vertebroplasty are bleeding, infection, and cement leakage, all can be prevented under carefully performing, patient selection, and radiology guidance with contrast. Cement leakage was classified as Yeom et al18 to vascular or cortical cement leakage, and epidural leakage was also reported. Trumm et al19 reported a 58% leakage rate, but others reported higher rates such as 77% from Tomé-Bermejo et al.20 Percutaneous vertebroplasty has proved its efficacy in pain control of malignant pathology.21 However, all treatment in most cases with 33% to 50% pain reduction is clinically meaningful,22 and the cancer would be almost out of control in the long run with more severe pain.

When treating the patients with cancer, it is important to provide the best care for individuals. In our case, after treatment with percutaneous vertebroplasty and multimodality therapy providing effective palliation of symptoms, the pain sensation subsided and the quality of life improved. The performance status under Karnofsky and ECOG scales was much improved. The patient could walk without any assistance, and continued to receive treatment for pancreatic cancer.

CONCLUSION

We report a rare case that severe lower back pain caused by osteoblastic metastasis of pancreatic cancer, and the patient was managed successfully via multimodality treatment. Our case highlights the benefits of multidisciplinary cancer treatment for such patient, preventing the complications such as immobilization accompanied with adverse effects like musculoskeletal, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems. All clinicians should be informed of the clinical findings to provide patients with suitable therapies and surveys.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, VAS = visual analog pain score.

Y-PC and W-TW contributed equally to this work.

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the authors or upon any organization with which the authors are associated.

The authors did not obtain written consent of the patient to describe his illness and publish this case report because the patient was lost to follow-up when we started work on the case study. We did not use patient data that would allow identifying him.

Ethics committee approval is not included as it is commonly accepted that case reports do not require such approval.

This work was supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW104-TDU-B-212-133019).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leinonen V, Kankaanpää M, Airaksinen O, et al. Back and hip extensor activities during trunk flexion-extension: effects of low back pain and rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81:32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12:6243s–6249s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borad MJ, Saadati H, Lakshmipathy A, et al. Skeletal metastases in pancreatic cancer: a retrospective study and review of the literature. Yale J Biol Med 2009; 82:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pneumaticos SG, Savidou C, Korres DS, et al. Pancreatic cancer's initial presentation: back pain due to osteoblastic bone metastasis. Eur J Cancer Care 2010; 19:137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao C, Domenico DR, Kim K, et al. Observations on the developmental patterns and the consequences of pancreatic exocrine adenocarcinoma: findings of 154 autopsies. Arch Surg 1995; 130:125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortiz A, Lin SH. Osteolytic and osteoblastic bone metastases: two extremes of the same spectrum? Recent Results Cancer Res 2012; 192:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46:765–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin JJ, Pollock CB, Kelly K. Mechanisms of cancer metastasis to the bone. Cell Res 2005; 15:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregory LS, Choi W, Burke L, et al. Breast cancer cells induce osteolytic bone lesions in vivo through a reduction in osteoblast activity in mice. PLoS One 2013; 8:e68103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joffe N, Antonioli DA. Osteoblastic bone metastases secondary to adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Clin Radiol 1978; 29:41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serena Lunardi, Ruth JMuschel, Thomas BBrunner. The stromal compartments in pancreatic cancer: are there any therapeutic targets? Cancer Lett 2014; 343:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sideras K, Braat H, Kwekkeboom J, et al. Role of the immune system in pancreatic cancer progression and immune modulating treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev 2014; 40:513–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2011; 378:607–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urch C. The pathophysiology of cancer-induced bone pain: current understanding. Palliat Med 2004; 18:267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lossignol DA, Dumitrescu C. Breakthrough pain: progress in management. Curr Opin Oncol 2010; 22:302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marc Röllinghoff, Kourosh Zarghooni, Klaus Schlüter-Brust, et al. Indications and contraindications for vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130:765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeom JS, Kim WJ, Choy WS, et al. Leakage of cement in percutaneous transpedicular vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic compression fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003; 85:83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trumm CG, Pahl A, Helmberger TK, et al. CT fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous vertebroplasty in spinal malignancy: technical results, PMMA leakages, and complications in 202 patients. Skeletal Radiol 2012; 41:1391–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomé-Bermejo F, Piñera AR, Duran-Álvarez C, et al. Identification of risk factors for the occurrence of cement leakage during percutaneous vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic or malignant vertebral fracture. Spine 2014; 39:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie P, Zhao Y, Li G. Efficacy of percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients with painful vertebral metastases: a retrospective study in 47 cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2015; 138:157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon DB, Dahl JL, Miaskowski C, et al. American Pain Society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management. American Pain Society Quality of Care Task Force. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1574–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]