Abstract

This study aims to clarify the prognostic value of the preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after potentially curative hepatic resection (HR). The prognostic value of the NLR for HCC patients has not been definitely reviewed by large studies, especially for those with different Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stages.

A consecutive sample of 963 HCC patients who underwent potentially curative HR was classified as having low or high NLR using a cut-off value of 2.81. Overall survival (OS) and tumor recurrence were compared for patients with low or high NLR across the total population, as well as in subgroups of patients in BCLC stages 0/A, B, or C. Clinicopathological parameters, including NLR, were evaluated to identify risk factors of OS and tumor recurrence after potentially curative hepatic resection. Multivariate analyses were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model or subdistribution hazard regression model.

Multivariate analyses showed that NLR (>2.81), tumor number (>3), incomplete capsule, serum albumin (≤35 g/L), alanine transaminase activity (>40 U/L), and macrovascular invasion were risk factors for low OS, whereas NLR (>2.81), tumor size (>5 cm), alpha fetal protein concentration (>400 ng/L), and macrovascular invasion were risk factors for low tumor recurrence. NLR > 2.81 was significantly associated with poor OS and tumor recurrence in the total patient population (both P < 0.001), as well as in the subgroups of patients in BCLC stages 0/A or B (all P < 0.05). Moreover, those with high NLR were associated with low OS (P = 0.027), and also with slightly higher tumor recurrence than those with low NLR for the subgroups in BCLC stage B (P = 0.058). Neither association, however, was observed among patients with BCLC stage C disease.

NLR may be an independent predictor of low OS and tumor recurrence after potentially curative HR in HCC patients in BCLC stages 0/A or B.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide, and China accounts for ∼50% of HCC cases and HCC-related deaths worldwide.1 Various treatments against HCC are commonly used and their efficacy has improved in recent decades; among them, hepatic resection (HR) is the most frequently used treatment in Asia for patients with resectable cancer,2 which the Barcelona Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system defines as stage 0/A disease.3,4 In fact, HR is often used to treat patients in later stages of HCC, especially in Asia, and work from our research group and others argues strongly that the surgery technique can be safe and effective for patients in BCLC stages B or C.5–8 Nevertheless, the prognosis of patients with HCC after HR remains unsatisfactory: disease recurs in up to 74% of patients with intermediate or advanced HCC within 5 years of surgery,8 and patients with advanced disease show hospital mortality up to 2.3% and overall morbidity up to 31.3%.6 This highlights the need to identify risk factors of poor prognosis and HCC recurrence after HR in patients at any BCLC stage of disease, in order to inform cancer treatment and management.

Several studies have established a significant correlation between systemic inflammation and poor survival in lung cancer, breast cancer, soft-tissue sarcoma, and renal cell carcinoma.9–12 The mechanisms underlying this correlation remain unclear. It has been suggested that cytokines and inflammatory mediators are upregulated in the inflammatory state, leading to repair of DNA damage, inhibition of apoptosis, and promotion of angiogenesis, all of which facilitate the proliferation and metastasis of malignant cells.13,14 The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a marker of systemic inflammation that has been linked to poor survival of HCC patients after liver transplantation, transarterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, treatment with sorafenib,15–18 and HR.19–21 On the other hand, 1 study failed to find an association of NLR with poor overall survival (OS) or recurrence-free survival (RFS) after liver transplantation,22 another study found no association of NLR with OS or RFS of HCC patients after curative HR in BCLC stage 0/A,23 and a third study recommended against using NLR to guide HCC treatment decisions.24

The present study aimed to help resolve the lack of consensus on whether NLR is a risk factor of low OS and/or high tumor recurrence in HCC patients after potentially curative HR in a relatively large sample size. We used subgroup analysis to examine these possible relationships separately in patients in BCLC stages 0/A, B, or C. The patients in this study were treated at a single large medical center in Guangxi Province (China), which has the highest incidence of HCC in the world.25–27

METHODS

Ethics Statements

This retrospectively study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Guangxi Medical University; it was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki 2013 edition. Written informed consent was obtained from patients, and patient records or information was anonymized before analysis.

Patients

This retrospective study examined a consecutive sample of HCC patients who underwent potentially curative HR at the Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Guangxi Medical University between January 2004 and December 2011. Clinicopathological baseline data and outcomes had been prospectively collected in the hospital's central database. Patients were included in the study if they (1) had primary HCC with no prior treatment, such as transarterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, or percutaneous ethanol injection; and (2) had preserved liver function (Child Pugh class A or B). Patients were excluded if their medical records were insufficient or if the records showed evidence of immunodeficiency, hematological disease, or bacterial infection.

Definitions

Potentially curative HR for HCC was defined as complete surgical removal of macroscopic tumor tissues. Incomplete capsule was defined as incomplete or absent of tumor capsule. Macrovascular invasion was defined as the presence of invasion in 1 or more of the following vessels, based on imaging and histology: main portal vein and its right/left branches, hepatic vein and its branches, superior mesenteric vein, or inferior vena cava. Tumor recurrence was defined based on histopathology or, in the absence of such evidence, on HCC diagnostic criteria used by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.8 HCC was staged according to the most recent reviews by the main authors of the BCLC system.28,29 The censoring criteria of OS was defined as patients loss to follow up and those still live in March 2015, and tumor recurrence was defined as those without tumor recurrence when they died and those without recurrence in March 2015.

Patients were defined as having high or low NLR depending on whether the ratio at admission was higher or lower than 2.81. Even though several cut-off values (5.00, 2.81, 2.00, and 2.31) of NLR for OS and/or RFS after HR in HCC patients was used,19–21,30 we selected the cut-off point of 2.81 from the study by Mano and coworkers.19 That study comprised 958 patients with the cut-off value derived from a time-dependent receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis, which can take full advantage of censored survival data for a diagnostic maker to assess prognosis.31

Continuous variables were categorized by the threshold with significant clinical value. For example, the patient with serum albumin (ALB) <35 g/L might be considered to have hypoproteinemia. Patient with alanine transaminase (ALT) >40 g/L might suffer from hepatic injury. Patient with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) >400 ng/mL might have poor OS and high recurrence rate.

Outcomes and Subgroup Analysis

Outcomes were OS and tumor recurrence. These outcomes were compared for patients with low or high NLR across all patients in the study population, as well as in 3 subgroups of patients with HCC in different BCLC stages: 0/A, B, or C.

Follow-Up

During the first year after HR, patients were followed up 4 to 6 times and then 2 times each year. At each follow-up time, patients were received blood examination including levels of serum markers of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, liver function testing, serum AFP concentration, and imageological examination such as abdominal ultrasonography, enhanced computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging, and chest radiography.32

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS19.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL) and R 3.2.2 (R Development Core Team) using a significance threshold of P < 0.05. Differences between patients with low or high NLR across all patients were assessed for significance using the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Survival curves of OS were estimated across the entire population and in subgroups using Kaplan–Meier analysis and compared to each other using the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses to identify risk factors for low OS were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. Competing risk (Gray Test) model was used for univariate analyses, whereas subdistribution hazard regression (Fine and Gray) model was used for multivariate analyses to identify risk factors of tumor recurrence.

RESULTS

During the study period, 1057 patients with HCC underwent potentially curative HR at our hospital. Of these, 94 were excluded because they underwent only palliative HR (n = 55), they were died of other diseases (n = 27), or baseline data in their medical records were incomplete (n = 12). In the end, 963 patients were included in the study (Table 1), of whom 227 (23.6%) had high preoperative NLR (> 2.81) and the remaining 736 (76.4%) had low NLR (≤ 2.81). Of all included patients, 18 were with BCLC stage 0 HCC, 593 with BCLC stage A HCC, 211 with BCLC stage B HCC, and 141 with BCLC stage C HCC. The median survival time was 49 months for OS among total population.

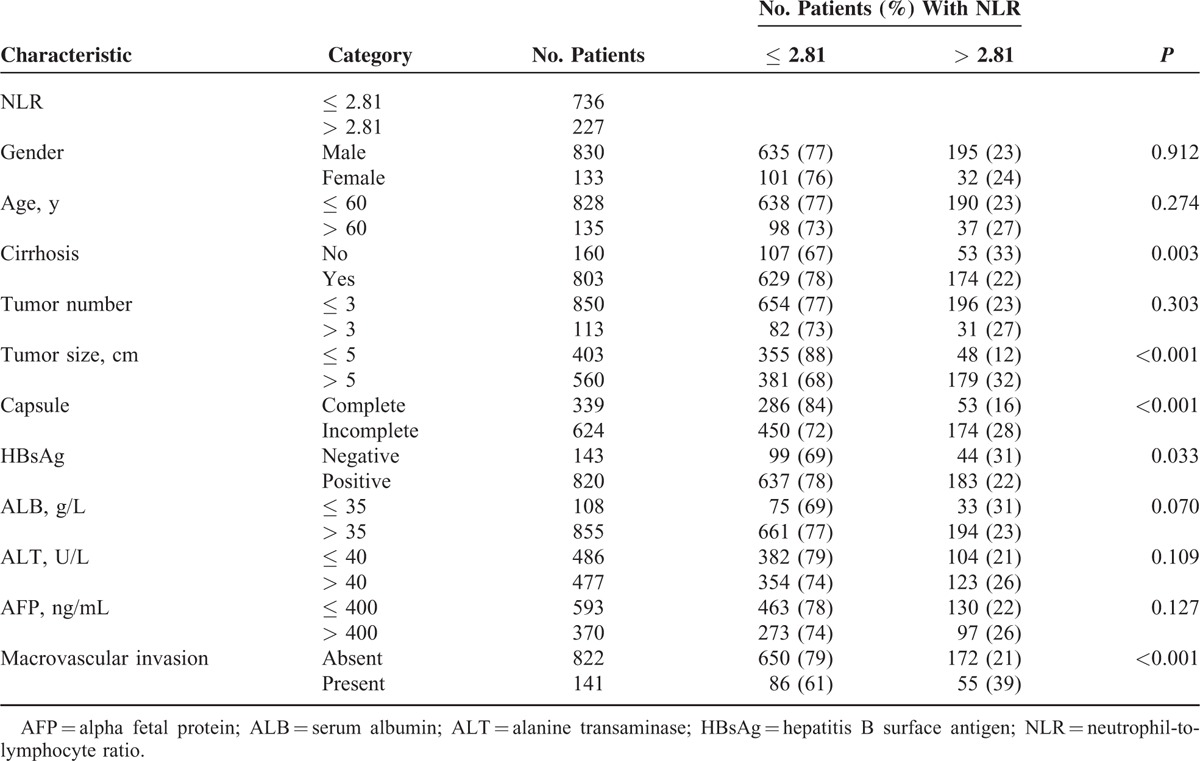

TABLE 1.

Association of Clinicopathological Characteristics With Low or High Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio

Preoperative NLR correlated significantly with cirrhosis (P = 0.003), tumor size > 5 cm (P < 0.001), incomplete capsule (P = 0.017), macrovascular invasion (P < 0.001), hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg; P = 0.033), ALB ≤ 40 g/L (P = 0.041), and ALT > 40 U/L (P = 0.006). NLR did not, however, correlate significantly with tumor number, age, gender, or AFP > 400 ng/mL (Table 1).

Risk Factors for Low OS or Tumor Recurrence

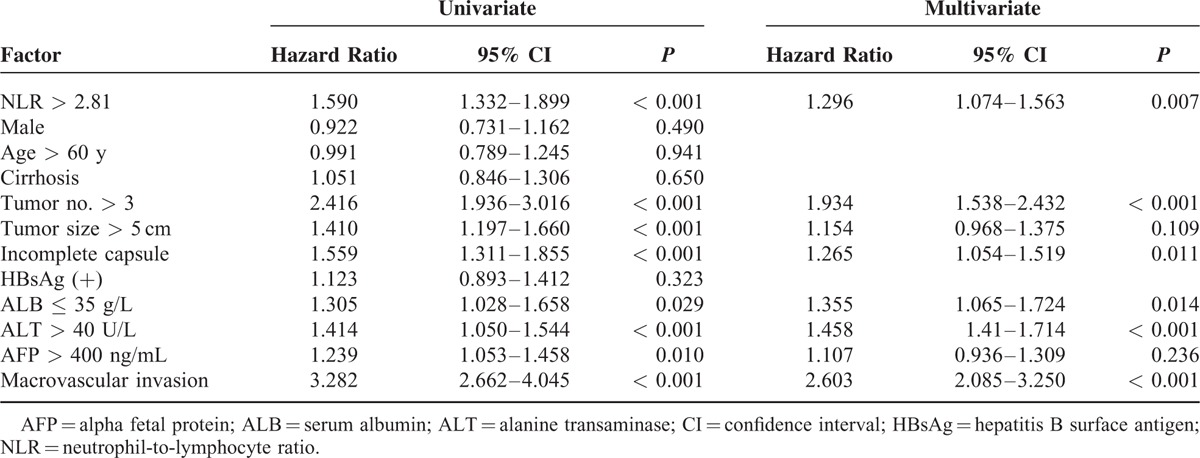

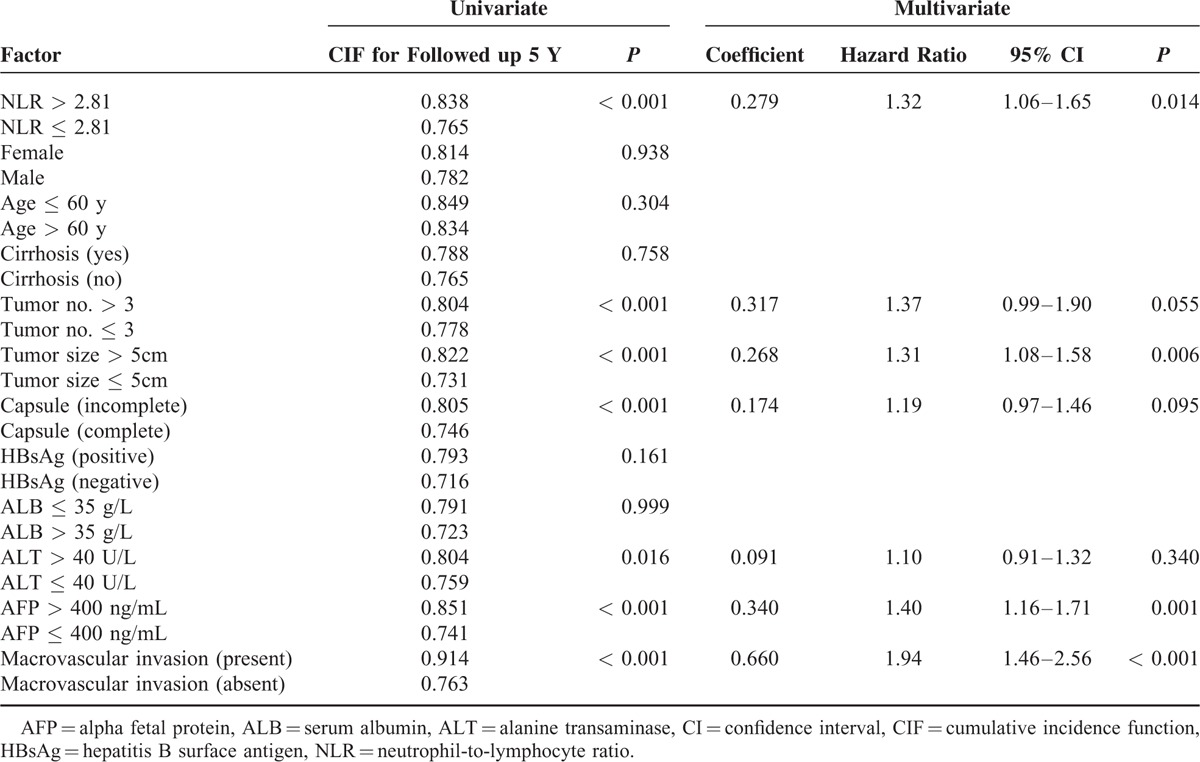

Multivariate analyses by the Cox proportional hazards model identified the following independent risk factors for low OS: NLR > 2.81, tumor number > 3, incomplete capsule, ALB ≤ 35 g/L, ALT > 40 U/L, and macrovascular invasion (Table 2). Multivariate analyses by subdistribution hazard regression (Fine and Gray) model found NLR > 2.81, tumor size > 5 cm, AFP > 400 ng/mL, and macrovascular invasion were risk factors of tumor recurrence (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Factors Predicting Overall Survival of Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Potentially Curative Resection

TABLE 3.

Factors Predicting Recurrence-Free Survival of Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Potentially Curative Resection, Univariate Analyses Using Competing Risk (Gray Test) Model and Multivariate Analyses Using Subdistribution Hazard Regression (Fine and Gray) Model

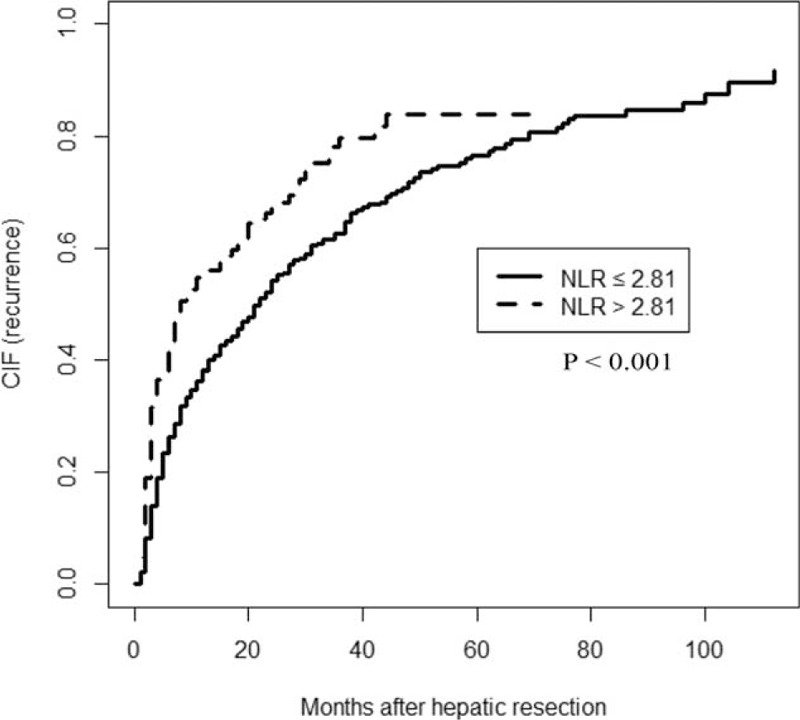

Comparison of Prognosis Between Patients With Low or High NLR, Regardless of BCLC Stage

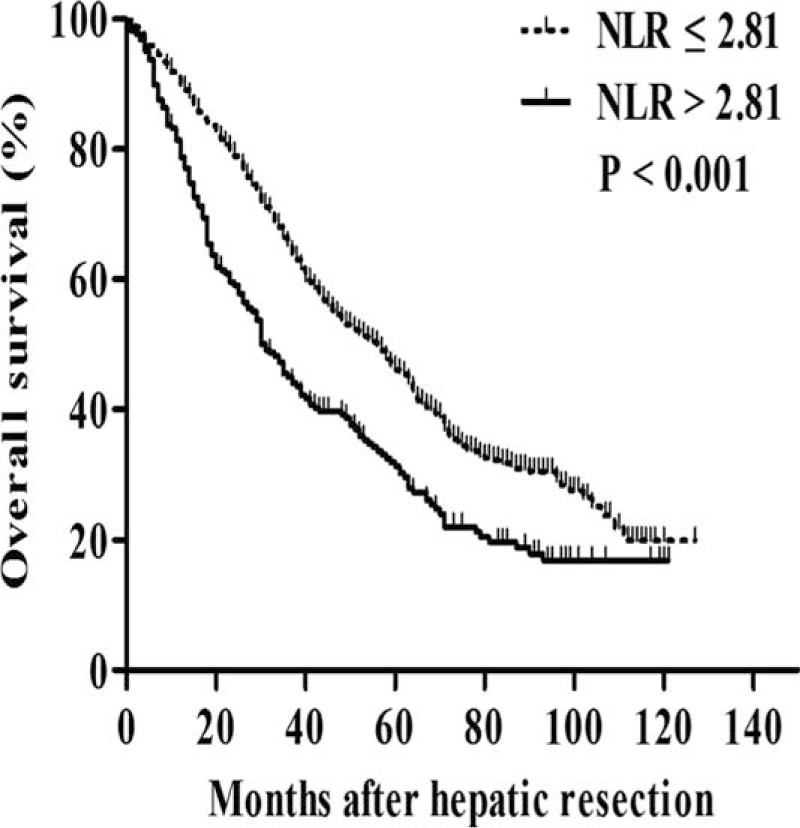

OS was significantly higher among patients with low preoperative NLR than among those with high NLR at 1 year (90.1% vs 78.8%), 3 years (65.3% vs 45.0%), and 5 years (46.1% vs 31.4%) (P < 0.001; Figure 1). Median survival time was 56 months among patients with low NLR, significantly longer than the median of 31 months among patients with high NLR. Moreover, patients with low NLR were with significantly lower rate of recurrence than those with high NLR (P < 0.001; Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing overall survival after potentially curative resection in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with a low or high preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). NLR = neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

FIGURE 2.

Competing risk (Gray Test) model comparing tumor recurrence after potentially curative resection in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with a low or high preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). NLR = neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Comparison of Prognosis Between Patients With Low or High NLR, Depending on BCLC Stage

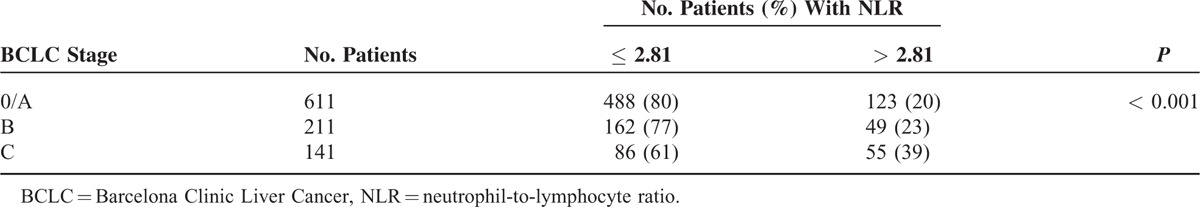

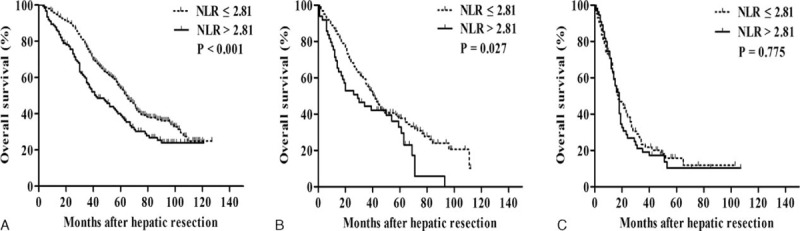

Pearson χ2 test analysis of subgroups of patients with HCC in BCLC stage 0/A, B, or C showed different relationships between low and high preoperative NLR (Table 4). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis among patients in BCLC stage 0/A, OS was significantly higher among patients with low NLR than among those with high NLR at 1 year (95.3% vs 87.8%), 3 years (75.7% vs 56.3%), and 5 years (54.0% vs 39.2%) (P < 0.001; Figure 3A). Similar results were observed among patients in BCLC stage B: 85.8% vs 71.4% at 1 year, 55.3% vs 44.3% at 3 years, and 37.8% vs 32.9% at 5 years (P = 0.027; Figure 3B). In contrast, no significant relationship was observed between NLR and OS among patients in BCLC stage C (P = 0.775; Figure 3C).

TABLE 4.

Association Between Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing overall survival after potentially curative resection in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with a low or high preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), stratified by the BCLC stage. Patients were in (A) stage 0/A, (B) stage B, or (C) stage C. BCLC = Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, NLR = neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

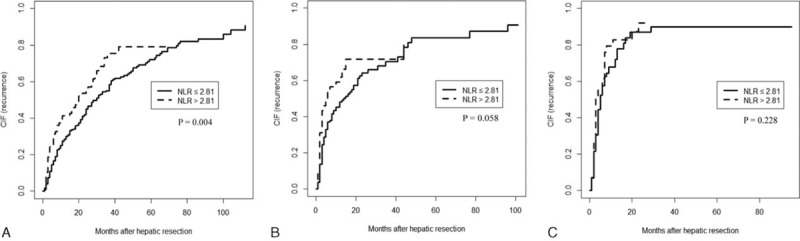

Tumor recurrence was significantly higher among patients with high NLR than among those with low NLR group for the subgroups in BCLC stage 0/A (P = 0.004; Figure 4A). Moreover, those with high NLR were also with slightly higher tumor recurrence than those with low NLR for the subgroups in BCLC stage B (P = 0.058; Figure 4B). However, for the subgroups in BCLC stage C, the 2 groups were with similar tumor recurrence (P = 0.228; Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Competing risk (Gray Test) model comparing tumor recurrence after potentially curative resection in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with a low or high preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), stratified by the BCLC stage. Patients were in (A) stage 0/A, (B) stage B, or (C) stage C.

DISCUSSION

HR is thought to be the most effective treatment for resectable HCC,33,34 and it can benefit even patients in intermediate or advanced stages of disease.35–37 However, a substantial proportion of patients treated by HR show poor prognosis and high risk of recurrence. In fact, 1 study found that 27.9% of HCC patients in BCLC stage A suffered from recurrence within 1 year after HR.38 The present study analyzed preoperative NLR as a candidate marker of poor prognosis in patients after HR and found high NLR to be a significant independent predictor of low OS in patients in BCLC stage 0/A or B, and high tumor recurrence only in patients in BCLC STAGE 0/A. Our data provide no evidence that high NLR is associated with risk of OS or tumor recurrence in patients with stage C disease.

Our results support previous studies associating NLR with poor prognosis after HR.19–21 Those studies analyzed mixed populations in various BCLC stages, whereas the present work provides the first assessment of NLR as a prognostic indicator according to BCLC stage. Our results conflict with 1 study reporting no association of NLR with OS or RFS among patients with BCLC stage 0/A HCC.23 The discrepancy may be due to the fact that we used a much larger sample size than they did (963 vs 324), or the fact that we used a different cut-off point for defining low and high NLR (2.81 vs 5). The value in our study was derived from time-dependent receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis of 958 patients,19 whereas their value was derived from receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis of 96 patients.21 We failed to find any evidence of association of NLR with OS or tumor recurrence in patients with stage C disease. This highlights the stage-specific nature of NLR as a disease indicator and prognostic marker. It also raises the question of whether other prognostic indicators reported in the HCC literature are clinically effective only for certain BCLC stages.

Why elevated preoperative NLR may be linked to poor prognosis after HR is unclear. Available evidence suggests that elevated NLR arises in part due to infiltration of macrophages into tumors,19 and it is associated with increased tumor-associated macrophage activity,39 leading to neutrophilia and/or lymphocytopenia.40 Neutrophils secrete several vascular endothelial growth factors that contribute to tumor angiogenesis,41 and neutrophil count correlates with tumor cell adhesion to hepatic sinusoids and tumor cell motility, which may be linked to tumor metastasis.42,43 Lymphocytopenia may lead to a decrease in the numbers of tumor-specific T cells, weakening antitumor immunity.44 Thus, elevated NLR appears to indicate relatively strong tumor-related inflammation and weak antitumor immune response.

Our findings suggest the potential usefulness of reducing elevated NLR before HR, at least in HCC patients in stages 0/A or B. One approach to reduce NLR may be antiviral treatment. As chronic infection with HBV or hepatitis C virus, which is strongly associated with HCC, can cause persistent inflammation that promotes tumor growth and metastasis,40 antiviral treatment may improve the systemic inflammation. Another approach may be immunopotentiation therapy, which may enhance antitumor immunity. Future studies should examine the potential clinical benefits of reducing NLR before HR.

The insights provided in the present work are limited by its retrospective design and by its failure to evaluate other systemic inflammation markers, such as levels of C-reactive protein or the ratio of platelets to lymphocytes. In addition, we applied an NLR cut-off value obtained in another study, instead of conducting our own receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis. Future studies should avoid these limitations in order to provide the most rigorous evidence possible.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AFP = alpha-fetoprotein, ALB = serum albumin, ALT = alanine transaminase, BCLC = Barcelona Liver Cancer, HbsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, HR = hepatic resection, NLR = neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, OS = overall survival, RFS = recurrence-free survival.

S-DL, Y-YW, and N-FP contributed equally to this study.

Funding: this work was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Special Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012ZX10002010001009), the Guangxi Science and Technology Development Projects (14124003-4), the Guangxi University of Science and Technology Research Projects (KY2015LX056), the Ministry of Health of Guangxi Province (GZPT1240, GZZC15-34, Z2015621, Z2014241, S201417-03), and the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (YCBZ2015030).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int 2010; 4:439–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012; 56:908–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman M, Bruix J, Porayko M, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma: the rationale for the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommendations. Hepatology 2012; 56:793–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong JH, Rodriguez AC, Ke Y, et al. Hepatic resection as a safe and effective treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma involving a single large tumor, multiple tumors, or macrovascular invasion. Medicine 2015; 94:e396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang T, Lin C, Zhai J, et al. Surgical resection for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2012; 138:1121–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu W, Zhou JG, Sun Y, et al. Hepatic resection improved the long-term survival of patients with BCLC stage B hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 19:1271–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhong JH, Ke Y, Gong WF, et al. Hepatic resection associated with good survival for selected patients with intermediate and advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2014; 260:329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao Y, Yuan D, Liu H, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is associated with response to therapy and prognosis of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2013; 62:471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azab B, Bhatt VR, Phookan J, et al. Usefulness of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in predicting short- and long-term mortality in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szkandera J, Absenger G, Liegl-Atzwanger B, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is associated with poor prognosis in soft-tissue sarcoma patients. Brit J Cancer 2013; 108:1677–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pichler M, Hutterer GC, Stoeckigt C, et al. Validation of the pre-treatment neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in a large European cohort of renal cell carcinoma patients. Brit J Cancer 2013; 108:901–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010; 140:883–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008; 454:436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limaye AR, Clark V, Soldevila-Pico C, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts overall and recurrence-free survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 2013; 43:757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan W, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios as predictors of survival and metastasis for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after transarterial chemoembolization. PloS One 2015; 10:e0119312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dan J, Zhang Y, Peng Z, et al. Postoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio change predicts survival of patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing radiofrequency ablation. PloS One 2013; 8:e58184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.da Fonseca LG, Barroso-Sousa R, Bento Ada S, et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio affects survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Med Oncol 2014; 31:264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mano Y, Shirabe K, Yamashita Y, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of survival after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Ann Surg 2013; 258:301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao W, Zhang J, Zhu Q, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a new prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Transl Oncol 2014; 7:248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomez D, Farid S, Malik HZ, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic predictor after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 2008; 32:1757–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parisi I, Tsochatzis E, Wijewantha H, et al. Inflammation-based scores do not predict post-transplant recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients within Milan criteria. Liver Transplant 2014; 20:1327–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan AW, Chan SL, Wong GL, et al. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) predicts tumor recurrence of very early/early stage hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22:4138–4148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan KM, Groeschl RT, Turaga KK, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of outcomes for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a Western perspective. J Surg Oncol 2014; 109:95–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang CY, Huang TR, Yu JH, et al. Epidemiological analysis of primary liver cancer in the early 21st century in Guangxi province of China. Chin J Cancer 2010; 29:545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang JS, Huang T, Su J, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma and aflatoxin exposure in Zhuqing Village, Fusui County, People's Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001; 10:143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61:69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruix J, Gores GJ, Mazzaferro V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical frontiers and perspectives. Gut 2014; 63:844–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forner A, Gilabert M, Bruix J, et al. Treatment of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014; 11:525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu SJ, Shen SL, Li SQ, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative peripheral neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma after radical hepatectomy. Med Oncol 2013; 30:721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics 2000; 56:337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong JH, Xiang BD, Gong WF, et al. Comparison of long-term survival of patients with BCLC stage B hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection or transarterial chemoembolization. PloS One 2013; 8:e68193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Truty MJ, Vauthey JN. Surgical resection of high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma: patient selection, preoperative considerations, and operative technique. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17:1219–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torzilli G, Belghiti J, Kokudo N, et al. A snapshot of the effective indications and results of surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in tertiary referral centers: is it adherent to the EASL/AASLD recommendations? an observational study of the HCC East-West study group. Ann Surg 2013; 257:929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhong JH, Ke Y, Wang YY, et al. Liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and macrovascular invasion, multiple tumours, or portal hypertension. Gut 2015; 64:520–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong JH, Lu SD, Wang YY, et al. Intermediate-stage HCC—upfront resection can be feasible. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015; 12:295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong JH, Wu FX, Li H. Hepatic resection associated with good survival for selected patients with multinodular hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2014; 35:8355–8358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang BL, Tan QW, Gao XH, et al. Elevated PIVKA-II is associated with early recurrence and poor prognosis in BCLC 0-A hepatocellular carcinomas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014; 15:6673–6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4:71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation cancer. Nature 2002; 420:860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kusumanto YH, Dam WA, Hospers GA, et al. Platelets and granulocytes, in particular the neutrophils, form important compartments for circulating vascular endothelial growth factor. Angiogenesis 2003; 6:283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu Y, Zhao Q, Peng C, et al. Neutrophils promote motility of cancer cells via a hyaluronan-mediated TLR4/PI3K activation loop. J Pathol 2011; 225:438–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDonald B, Spicer J, Giannais B, et al. Systemic inflammation increases cancer cell adhesion to hepatic sinusoids by neutrophil mediated mechanisms. Int J Cancer 2009; 125:1298–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 2011; 331:1565–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]