Abstract

Introduction: Neisseria meningitidis (N. meningitidis) is associated with severe invasive infections such as meningitis and fulminant septicemia. Septic arthritis due to N. meningitidis is rare and bone infections have been reported exceptionally. We report the case of a 1-year old girl who presented with a painful, swollen right knee, accompanied by fever and agitation. Arthrocentesis of the right knee, while patient was under anesthesia, yielded grossly purulent fluid, so we made arthrotomy and drainage. The culture from synovial fluid revealed N. meningitidis, sensitive to Ceftriaxone. The patient received intravenous antibiotherapy with Ceftriaxone. The status of the patient improved after surgical drainage and intravenous antibiotic therapy. She recovered completely after 1 month.

Conclusion: This observation illustrates an unusual presentation of invasive meningococcal infection and the early identification of the bacteria, combined with the correct treatment, prevent the complications and even death.

INTRODUCTION

Neisseria meningitidis is associated with severe invasive infections such as meningitis and fulminant septicemia. Septic arthritis due to N. meningitidis is uncommon and bone infections have been reported exceptionally.1

There is a concomitant septic arthritis in 11% of cases of meningococcemia. We describe below a rare clinical case of a 1-year-old girl with primary meningococcal arthritis (PMA) without meningococcemia.

CASE REPORT

A Caucasian 1-year old girl presented to the Emergency Department with a painful, swollen right knee accompanied by fever and agitation. She was unable to move it or bear weight on it. There was no history of close contact with other children, no history of respiratory or urinary tract infections. Our patient had never received meningococcal vaccination. Her body temperature was 38.6 °C. There was no skin rash. There was no neck rigidity or photophobia. The knee examination revealed an erythematous, warm, swollen right knee that was diffusely tender to palpation. Active and passive range of motion was severely limited secondary to pain. The peripheral blood white cells count was 22.74 × 103, Neutrophils = 75.0%, Lymphocytes = 16.9%, Monocytes = 7.8%, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) = 53 mm/1 hour, C-reactive protein (CRP) = 49.45 mg/L. Two sets of blood cultures were performed. Both blood cultures were negative for any bacteria after incubation for 5 days. X-ray of the right lower limb did not reveal any bone lesions (Figure 1). Arthrocentesis of the right knee, while the patient was under anesthesia, yielded grossly purulent fluid, so we made arthrotomy and drainage. We made also, puncture of the right hip to exclude the diagnosis of osteoarthritis. Microscopic examination of synovial fluid revealed numerous polymorphonuclear neutrophils with intracellular Gram-negative diplococci. The synovial fluid culture revealed N. meningitidis serogroup C, sensitive to Ceftriaxone. The patient received intravenous Ceftriaxone for 12 days (1 g/day) and continued to take oral Cefuroxime for another 2 weeks. The evolution of the patient was favorable, removing the drain on 5th day after surgery. She showed full recovery at later follow-up.

FIGURE 1.

X-ray of the right lower limb.

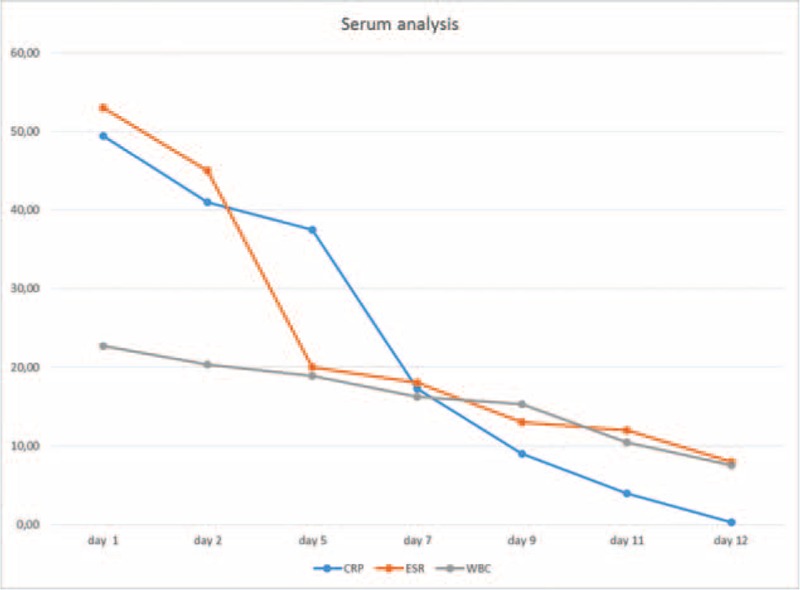

The patient responded well to the treatment over 12 days. The white blood cells, CRP, and ESR have fallen consistently (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Serum analysis of WBC, CRP, and ESR levels during treatment. CRP = C reactive protein, ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate, WBC = white blood count.

We evaluated the patient in each month, for 6 months, with the monitoring of blood count, ESR, and CRP, which were maintained within normal limits.

DISCUSSION

PMA is an uncommon form of meningococcal disease. PMA is defined as acute septic arthritis without meningitis or classical syndrome of meningococcemia, defined as the combination fever, rash, and hemodynamic instability.2 Giamarellos-Bourboulis et al3 reported 34 cases of PMA in literature from 1980 to 2002.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most likely causative agent of septic arthritis, occurring in 44% of cases.4Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas are much less common. These gram-negative bacteria affect newborns and patients with immunodeficiencies. It was reported that N. gonorrhoea is a frequent cause of septic arthritis in young people. N. meningitidis is a less common cause of septic arthritis. Its predilection for causing oligo articular infection makes it difficult to separate it from disseminated gonococcal infection.5–8

Our child presented with only 1 joint arthritis, associated with rash and a clinical differential diagnosis was difficile. The presentation of PMA can be very similar to other septic arthritis and it can be identical with arthritic disease induced by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Both bacteria have an affinity to cause oligo articular arthritis associated with rash. Direct bacterial invasion of the synovium via blood-borne infection is the proposed pathogenesis of PMA, with approximately 40% from patients having positive blood culture.9 Symptoms of an upper respiratory infection precede the arthritis up to 50% of cases;8 a maculopapular rash is another sign, observed in 30% of cases.5,9 In our case, the infant had no history of respiratory or urinary tract infections.

The clinical spectrum of meningococcal infections ranges from asymptomatic carriage to fulminant sepsis, with meningitis and septicemia. However, the ability of the organism to cause focal disease is often overlooked.10 Effort was made to classify the various presentations according to the clinical types and pathogenic mechanisms. Schaad postulated that 4 different mechanisms may be involved:

direct bacterial invasion of the synovium-septic arthritis.

hypersensitivity reaction-allergic arthritis.

intra-articular hemorrhage – hemarthrosis.

iatrogenic causes9

Although arthritis has been observed in approximately 7% of meningococcal infections, PMA is uncommon. A review of the literature found 46 reported patients – children and adults – with meningococcal joint infections without meningeal symptoms. Of the 46 patients, 19 involved isolated joints. Of these, the knee was the most common – 11 patients, followed by the ankle. Approximately 50% of patients were children younger than 4 years old.11,12 In this review, we can add our 1-year old girl with meningococcal infection in only 1 joint.

In our case, the synovial fluid culture revealed N. meningitidis serogroup C, but in our country there were no epidemics with this organism, and the PMA serogroup C is the only case reported in a 1-year old child.

Searching PubMed database about Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C causing primary arthritis, we found a few results (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Reported Cases of Primary Arthritis With Neisseria meningitidis Serogroup C

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique is sometimes used to identify various strains of meningococci from the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or other normally sterile sites with validity comparable to that of culture-based diagnosis. It provides a complementary tool of classic culture and often enhances confirmatory results. The distinction between gonococcal arthritis (N. gonorrhoeae) and meningococcal arthritis (N. meningitidis) may be difficult. On microscopic examination of knee aspirate N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae are morphologically indistinguishable and cultures may be negative, especially if antimicrobial agents have been given.20 PCR can provide a specific diagnosis in such cases. Also, PCR does not require organisms to be viable.21 In our case, the result of the culture was positive, so it was not necessary to perform the PCR technique.

Vaccination remains the best control strategy to prevent invasive meningococcal disease, but our infant did not received meningococcal vaccination. He had no risk factors in history and in our country this vaccine is optional and it is not covered by the national health system.

Septic arthritis is a medical emergency that needs prompt recognition and treatment to prevent local disruption of the joint and peripheral circulation of infection. Initial diagnosis of septic arthritis is obvious. The patient presents with fever and a warm, swollen, and tenderness joint. The knee is the most frequent involved.20 Further evaluation of septic arthritis includes arthrocentesis of affected joint, complete blood cell count, and peripheral blood cultures. The synovial fluid should be cultured, gram-stained, and analyzed for cell count to help with initial management.22,23 The synovium is positive for meningococcus in 90 % of PMA cases, the blood cultures are positive only in 40% of PMA cases.22

CONCLUSIONS

Our case confirms the data from the literature that N. meningitidis does not appear to be aggressive toward hyaline cartilage. Complete recovery does usually occur, provided appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy, joint aspiration, and/or washout are performed early.

This observation illustrates an unusual presentation of invasive meningococcal infection and the early identification of the bacteria, combined with the correct treatment, prevented the complications and even death.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the child for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Anca Gabriela Savu, Intensive Care, Dr Letitia Doina Duceac, Epidemiology, and Dr Elena Petraru, Microbiology, from the “St. Mary” Children Emergency Hospital, Iasi, for their help in managing this patient.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CRP = C-reactive protein, ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, PMA = primary meningococcal arthritis.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schaad UB. Arthritis in disease due to Neisseria meningitidis. Rev Infect Dis 1980; 2:880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells M, Gibbons R. Primary meningococcal arthritis: case report and review of literature. Mil Med 1997; 769–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Grecka P, Toskas A. Primary meningococcal arthritis: case report and clinical review. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2002; 553–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross JJ, Salzman CL, Carling P, et al. Pneumococcal septic arthritis – review of 190 cases. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harwood MI, Womack J, Kapur R. Primary meningococcal arthritis. J Am Board Fam Med 2008; 21:66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidd BL, Hart HH, Grigor RR. Clinical features of meningococcal arthritis: a report of four cases. Ann Rheum Dis 1985; 790–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinals RS, Ropes MW. Meningococcal arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1964; 241–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernando NK, Gupta YK. Purulent meningococcal arthritis in an adult. J Med Soc NJ 1980; 590–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaad UB. Arthritis in disease due to N. meningitidis. Rev Infect Dis 1980; 880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillon M, Nource C, Dowling F, et al. Primary meningococcal arthritis. Pediatric Infect Dis J 1997; 16:331–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weels M, Gibbons RB. Primary meningococcal arthritis. Case report and review of the literature. Mil Med 1997; 162:769–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Muderis M, Mo YK, Boyle S. Primary septic arthritis of the knee due to Neisseria meningitides. Hong Kong J Orthop Surg 2003; 7:43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joice M, Laing A, Mullet H. Isolated septic arthritis: meningococcal infection. J R Soc Med 2003; 237–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christiansen JC. Primary meningococcal arthritis caused by Neisseria meningitidis. One of the many manifestations of meningococcal disease. Ugeskr Laeger 1995; 157:3909–3910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cartolano GL, Le Lostec Z, Chéron M, et al. Primary meningococcal arthritis of the knee: contribution of synovial liquid culture in blood-culture vial. Rev Méd Interne 2001; 22:75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Grecka P, Petrikkos G, et al. Primary meningococcal arthritis: a case report and review. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2002; 20:553–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joyce M, Laing A, Mullet H, et al. Isolated septic arthritis: meningococcal infection. J R Soc Med 2003; 96:237–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harwood M, Womack J, Kapur R. Primary meningococcal arthritis. J Am Board Fam Med 2008; 21:66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garner A, Sundram F, Harris K. Group C Neisseria meningitidis as a cause of septic arthritis in a native shoulder joint: a case report. Case Rep Orthop 2011; 2011:862487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klatte TO, Lehmann W, Rueger JM. [Primary meningococcal infection of the knee. A rare cause of septic arthritis]. Unfallchirurg 2015; 118:885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edgeworth JD, Nicholl JE, Eykyn SJ. Diagnosis of primary meningococcal arthritis using the polymerase chain reaction. J Infection 1998; 37:199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCulloch M, Brooks H, Kalantarinia K. Isolated polyarticular septic arthritis: an atypical presentation of meningococcal infection. Am J Med Sci 2008; 323–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karim I, Carvalho N. Infection and immune mediated meningococcal associated arthritis: combination features in the same patient. Rev Inst Meds Sao Paulo 2012; 54:109–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]