Abstract

Background

Although we previously demonstrated that activation of central nervous system (CNS) melanocortin3/4 receptors (MC3/4R) play a key role in blood pressure (BP) regulation, especially in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs), the importance of hindbrain MC4R is still unclear.

Method

In the present study, we examined the cardiovascular and metabolic effects of chronic inhibition of MC3/4R in the hindbrain of SHRs and normotensive Wistar–Kyoto (WKY) rats. Male WKY rats (n = 6) and SHRs (n = 7) were implanted with telemetry probes to measure BP and heart rate (HR) 24 h/day, and an intracerebroventricular cannula was placed into the fourth ventricle. After 10 days of recovery and 5 days of control measurements, the MC3/4R antagonist (SHU-9119) was infused into the fourth ventricle (1 nmol/h) to antagonize hindbrain MC4R for 10 days, followed by a 5-day recovery period.

Results

Chronic hindbrain MC3/4R antagonism significantly increased food intake and body weight in WKY rats (17 ± 1 to 35 ± 2 g/day and 280 ± 8 to 353 ± 8 g) and SHRs (19 ± 2 to 35 ± 2 g/day and 323 ± 7 to 371 ± 11 g), and markedly increased fasting insulin and leptin levels while causing no changes in blood glucose levels (99 ± 4 to 87 ± 4 and 89 ± 5 to 89 ± 4 mg/dl, respectively, for WKY rats and SHRs). Chronic SHU-9119 infusion reduced mean arterial pressure and HR similarly in WKY rats (−8 ± 1 mmHg and −47 ± 3 b.p.m.) and SHRs (−11 ± 3 mmHg and −44 ± 3 b.p.m.).

Conclusion

These results suggest that although hindbrain MC4R activity contributes to appetite and HR regulation, it does not play a major role in mediating the elevated BP in SHRs.

Keywords: blood pressure, central nervous system, food intake, heart rate, melanocortin system

INTRODUCTION

The central nervous system (CNS) melanocortin system plays an important role in regulating energy balance and body weight homeostasis. Several hormones that control body weight, such as leptin and insulin, stimulate pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons which release α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) – an agonist for melanocortin 4 receptors (MC4R). Activation of MC4R, in turn, leads to suppression of appetite and increased energy expenditure via augmented sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) to thermogenic tissues [1–3].

In addition to its powerful effects on energy balance, acute and chronic MC4R activation stimulates SNA to tissues that regulate cardiovascular function, including the kidneys, and heart and blood vessels, leading to increased blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR). Studies in humans as well as in experimental animal models suggest that a functional MC4R may be required for obesity to be associated with increased SNA and hypertension. For instance, humans with dysfunctional MC4R exhibit severe obesity and many characteristics of the metabolic syndrome, but are not hypertensive, and actually have lower BP, reduced SNA to different stimuli such as inspiratory hypoxia, and lower prevalence of hypertension than control obese individuals [4]. Similar phenotypes are observed in MC4R-deficient mice which are not hypertensive despite severe obesity, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and other features of the metabolic syndrome [5].

Previous studies from our laboratory suggest that the brain melanocortin system may play an important role in BP regulation beyond obesity-induced hypertension. For instance, we found that chronic infusion of MC3/4R antagonist into the lateral ventricles of lean spontaneous hypertensive rats (SHRs), a model of hypertension associated with high sympathetic tone, markedly reduced their BP to the same degree as accomplished by adrenergic receptor blockade [6]. In addition, chronic MC3/4R antagonism markedly reduced the hypertension induced by chronic nitric oxide synthase inhibition using NG-nitro-L-argenine methyl ester (L-NAME) in lean Sprague–Dawley rats [7]. Therefore, the CNS melanocortin system appears to play a more fundamental role in regulating SNS activity and BP than previously appreciated. However, the specific contribution of hindbrain MC4R activity in long-term regulation of SNS and BP is still unknown.

Balthasar et al. [8] showed that rescuing MC4R in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) and amygdala prevented 60% of the obesity observed in whole-body MC4R-deficient mice, but did not alter energy expenditure [8], whereas we observed that selective rescue of MC4R in POMC neurons resulted in increased energy expenditure compared to MC4R-deficient mice [9]. This suggests that there may be divergent control of appetite, metabolic function, and SNA by MC4R located in different areas of the brain. However, there have been no studies, to our knowledge, that have investigated the role of MC4R in the hindbrain in regulating metabolic and cardiovascular function or in contributing to elevated BP in SHRs. Therefore, to test the hypothesis that hindbrain MC4R play a role in BP and HR regulation, and contribute to the hypertension in SHRs, we chronically infused the MC3/4R antagonist, SHU-9119, into the fourth ventricle of SHRs and normotensive Wistar–Kyoto (WKY) rats treated as controls to specifically target the hindbrain. We found that chronic fourth ventricle MC3/4R blockade caused marked hyperphagia and weight gain while causing significant reductions in HR in SHRs and WKY controls, but failed to substantially attenuate hypertension in SHRs.

METHODS

All experimental procedures conformed to the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Animal surgery

Male SHRs (n = 8) and WKY rats (n = 6) weighing between 275 and 325 g (15–17-week-old; Harlan, Inc, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), and atropine sulfate (0.37 mg/kg) was administered to prevent excessive airway secretion. A telemetry BP transmitter (Model TA11PAC40; Data Sciences International, Minnesota, USA) was implanted in the abdominal aorta distal to the kidneys under sterile conditions as previously described [10]. A stainless steel cannula (26 gauge, 10 mm long) was also implanted into the fourth ventricle using the following coordinates: from bregma, 0.0 mm lateral, 12.0 mm caudal, and 6.3 mm ventral from the surface of the skull [11]. After surgery, the rats were housed individually and received water and food ad libitum (Harlan Teklad, #170955, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). The rats were allowed to recovery from surgery for 10–12 days before control measurements were taken, and then we began monitoring food intake, body weight, BP, and HR. At the end of experiments, accuracy of the cannula was examined by histological evaluation after acute injection of Evan’s Blue. Although fourth-ventricle infusions have been widely used to target brainstem neurons, we also tested by infusion of Evan’s blue dye and found that large areas of the fourth ventricle, the whole ventral surface of the medulla oblongata, and parts of the pons were found to be stained; the staining, however, did not extend to the lateral or third ventricles.

Experimental protocols

Mean arterial pressure (MAP), HR, and food intake were recorded daily. After a 5-day control period, the MC3/4R antagonist, SHU-9119, was infused intracerebroventricularly (1 nmol/h at 0.5 µl/h) for 10 consecutive days via osmotic minipump (model 2002; Durect Corp., Cupertino, California, USA). Under isoflurane anesthesia, the osmotic minipump was implanted subcutaneously in the scapular region and connected to the intracerebroventricular (ICV) cannula using tygon tubing (Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, Illinois, USA). The rate of SHU-9119 infusion was based on previous studies showing that this dose effectively blocks MC4R and increases food intake, promotes weigh gain, and reduces BP and HR [6]. On the last day of SHU-9119 infusion, the cannula connecting the minipump with the ICV cannula was severed to stop the infusion, and the rats were followed for an additional 5-day post-treatment period. All animals were fasted for 5 h before blood samples (200 µl) were collected via a tail snip once during control, on day 10 of SHU infusion, and on day 5 of post-treatment period.

Analytical methods

Plasma leptin and insulin were measured using ELISA kits [R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) and Chrystal Chem (Downers Grove, Illinois, USA), respectively]. Plasma glucose was determined using the glucose oxidation method (Beckman glucose analyzer 2).

Statistical methods

The results are expressed as means ± SEM. The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test for comparisons between control and experimental values within each group when appropriate. Comparisons between different groups were made by two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test when appropriate. Statistical significance was accepted at a level of P less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Food intake and body weight responses to chronic hindbrain melanocortin-4 receptor antagonism

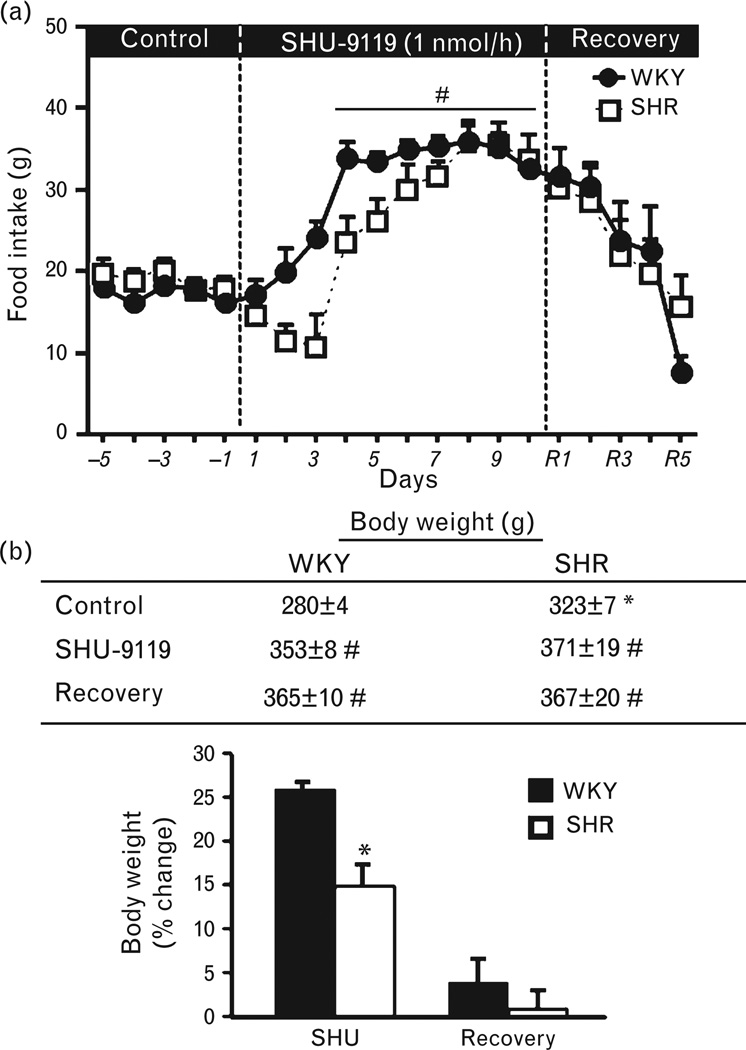

In SHRs and WKY rats, chronic hindbrain MC4R antagonism for 10 consecutive days markedly increased appetite, with food intake almost doubling by the end of treatment (Fig. 1a). After the infusion of SHU-9119 was stopped, food intake gradually decreased and returned back to baseline values in both groups by day 3 of the post-treatment period (Fig. 1a). The increase in food intake was associated with a 15 and 26% increase in body weight in SHRs and WKY rats, respectively (Fig. 1b).

FIGURE 1.

(a) Food intake responses and (b) body weight and percentage change in body weight in response to chronic fourth-ventricle infusion of the MC3/4R antagonist SHU-9119 (1 nmol/h) in WKY rats and SHRs. (*) P < 0.05 compared to WKY rats. (#) P < 0.05 compared to control period. MC3/4R, melanocortin3/4 receptors; SHRs, spontaneously hypertensive rats; WKY, Wistar–Kyoto.

Mean arterial pressure and heart rate responses to chronic hindbrain melanocortin-4 receptor antagonism

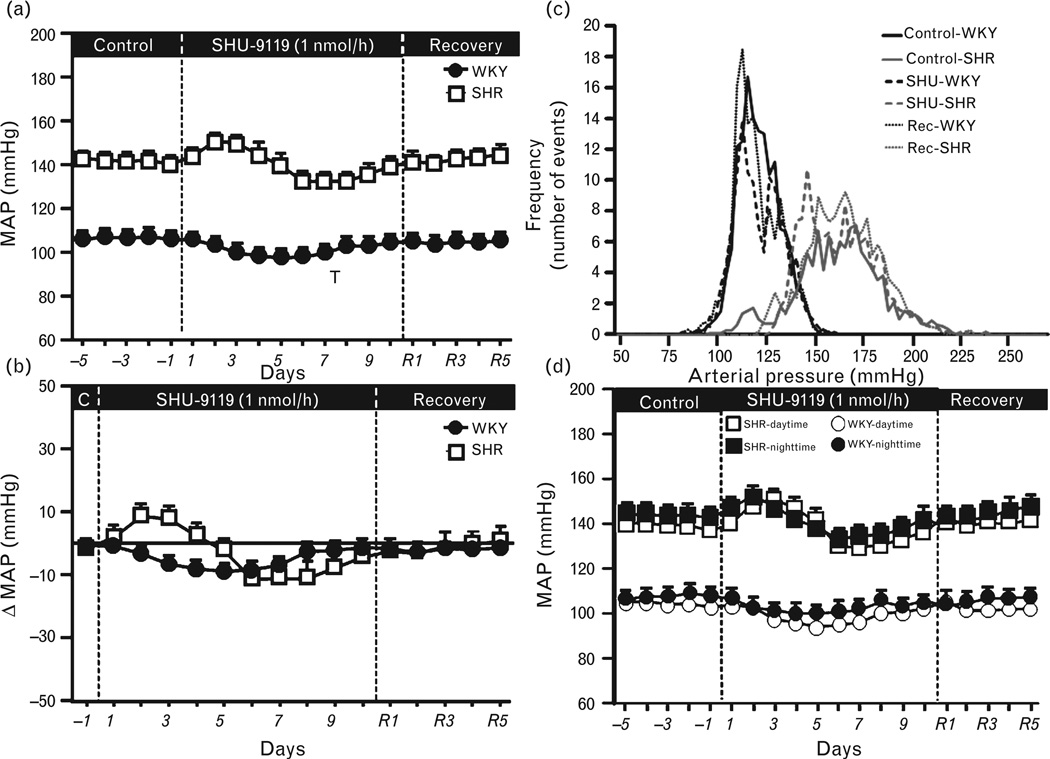

As expected, baseline MAP was higher in SHRs (142 ± 4 mmHg) compared to WKY rats (106 ± 2 mmHg), whereas HR was approximately 10 b.p.m. lower in SHRs. Chronic MC4R antagonism reduced MAP by approximately 8 mmHg in WKY rats during the first 7–8 days of treatment after which MAP gradually returned back toward control values (Fig. 2a and b). A similar fall in BP during chronic SHU-9119 infusion was observed in SHRs (Fig. 2a and b), except that BP increased slightly during the first 3 days of treatment before falling to approximately 11 mmHg below baseline values. Overall, the integrated area under the curve (AUC) for the change in BP during MC3/4R blockade was not different between groups (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

(a) Mean arterial pressure (MAP), (b) changes in MAP during chronic fourth-ventricle infusion of the MC3/4R antagonist SHU-9119 (1 nmol/h), (c) frequency of distribution of SBP, and (d) daytime and night-time MAP during control, SHU-9119 infusion, and recovery period in WKY rats and SHRs. The effects of chronic fourth-ventricle SHU-9119 infusion on 24-h BP variability values were obtained on days 3 and 4 of control, days 8 and 9 of SHU-9119 infusion, and on the last 2 days of the recovery (Rec) post-treatment period. BP, blood pressure; MC3/4R, melanocortin3/4 receptors; SHRs, spontaneously hypertensive rats; WKY, Wistar–Kyoto.

We also assessed the effects of chronic fourth-ventricle SHU-9119 infusion on 24-h BP variability, and found that although SBP frequency distribution was shifted to the right in SHRs compared to WKY controls, highlighting their elevated BP, chronic MC3/4R antagonism caused only a small shift to the left of the SBP frequency distribution in both groups without changing the BP variability (Fig. 2c). The effects of MC3/4R blockade on BP were similar during the light and dark periods (Fig. 2d).

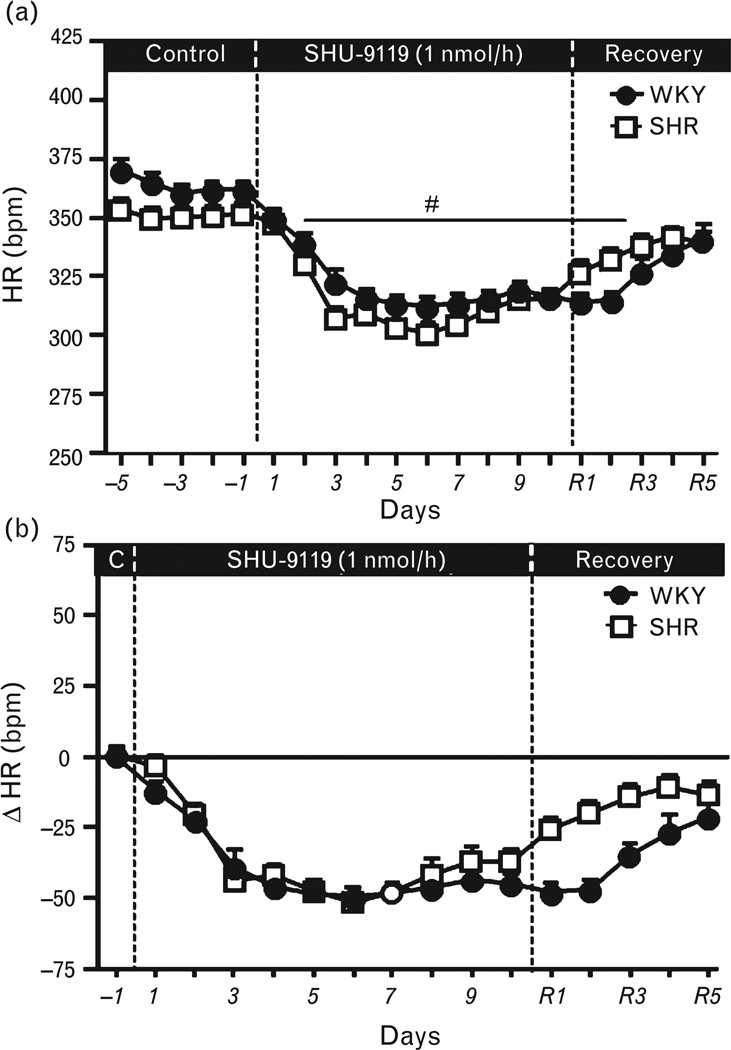

Chronic MC4R blockade caused a marked reduction in HR in both groups (Fig. 3a and b). This fall in HR occurred despite increased food intake and rapid body weight gain, which is usually associated with increased HR. These results, therefore, suggest that although hindbrain MC3/4R activity is important for appetite and HR regulation, it does not play a major role in contributing to the elevated BP in SHRs. However, tonic MC3/4 activation in the hindbrain does appear to contribute, in part, to baseline BP in both WKY rats as well as SHRs since chronic fourth-ventricle infusion of the MC3/4 R antagonist decreased BP by 8–11 mmHg in both groups.

FIGURE 3.

(a) Heart rate (HR) and (b) changes in HR during chronic fourth-ventricle infusion of the MC3/4R antagonist SHU-9119 (1 nmol/h) in WKY rats and SHRs. (#) P <0.05 compared to control period. MC3/4R, melanocortin3/4 receptors; SHRs, spontaneously hypertensive rats; WKY, Wistar–Kyoto.

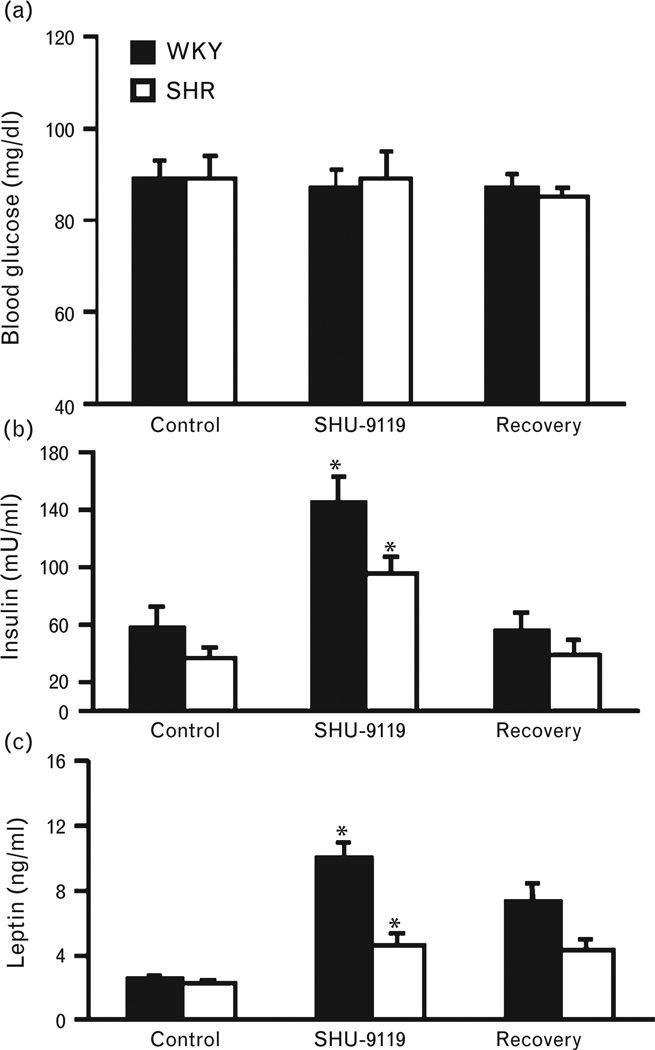

Plasma glucose, insulin, and leptin responses to chronic hindbrain melanocortin-4 receptor antagonism

Chronic MC4R blockade did not significantly alter fasting plasma glucose levels in WKY rats or SHRs (Fig. 4a). At baseline, WKY rats and SHRs exhibited similar plasma leptin levels (2.6 ± 0.2 and 2.3 ± 0.1 ng/ml), whereas fasting insulin levels were higher in WKY rats compared to SHRs (57.5 ± 14.5 vs. 37.2 ± 7.5 µU/ml). Chronic SHU-9119 infusion in the fourth ventricle significantly increased plasma leptin and insulin levels in both groups (Fig. 4b and c), likely as a result of the marked hyperphagia and rapid weight gain that occurred in both groups.

FIGURE 4.

(a) Fasting plasma glucose, (b) leptin, and (c) insulin levels during chronic fourth-ventricle infusion of the MC3/4R antagonist SHU-9119 (1 nmol/h) in WKY rats and SHRs. (#) P <0.05 compared to baseline. MC3/4R, melanocortin3/4 receptors; SHRs, spontaneously hypertensive rats; WKY, Wistar–Kyoto.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated that chronic MC3/4R antagonism in the hindbrain results in comparable increases in appetite and reductions in HR in normotensive rats as well as in SHRs. In addition, we observed similar and modest effect of hindbrain MC4R blockade to lower BP in WKY rats and SHRs.

Previous studies have demonstrated an important role of the brain melanocortin system in modulating SNA and controlling BP and HR. For example, acute ICV injections of MC4R agonists raise SNA to several tissues, including the kidneys [12–14]. Also, α and β-adrenergic receptor blockade completely prevents the hypertension caused by chronic central MC4R stimulation [15], suggesting that the SNA plays a key role in mediating the effects of MC4R activation on BP.

In the present study, we tested if MC3/4R located in the hindbrain plays a fundamental role in control of appetite, as well as in BP and HR regulation, and whether they contribute to the hypertension in SHRs. We found that endogenous hindbrain MC4R activity is important in appetite and HR regulation, but does not play a major role in the elevated BP of SHRs. These observations reinforce the notion of divergent control of metabolic and cardiovascular function by the brain melanocortin system. In contrast to our previous findings, showing that lateral ventricle infusion of SHU-9119 markedly reduced BP in SHRs (~22 mmHg), comparable to the effect of combined α and β-adrenergic blockade [6], we found that infusion of the MC3/4R antagonist into the fourth ventricle had only a modest effect on BP in SHRs, similar to the effects observed in normotensive WKY rats. Together, these findings suggest that endogenous MC3/4R activity in the forebrain (most likely in the hypothalamus) plays a key role in contributing to the elevated sympathetic tone and increased BP in SHRs. Previous observations from acute studies and baseline phenotypes of transgenic mice suggest that activation of MC4R in certain areas of the brain exert a differential control of energy expenditure, appetite, glucose homeostasis, BP, and HR regulation [12–14]. However, the neuronal populations involved in mediating the long-term effects of MC4R on appetite and cardiovascular function are still unknown. Although MC4R have been reported to be localized in cholinergic preganglionic neurons of the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS)/dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) and intermediolateral nucleus (IML) of the brainstem/spinal cord, as well as in the PVN, lateral and dorsomedial portions of the hypothalamus, the importance of brainstem MC4R in regulating cardiovascular and metabolic function has not been previously elucidated. Therefore, the precise regions and neuronal populations responsible for the long-term effects of MC3/4R on food intake regulation and cardiovascular function are still poorly understood and represent an important area for further investigation.

Although the BP-lowering effect of hindbrain MC3/4R antagonism in SHRs was modest compared to antagonism of forebrain MC3/4R observed in our previous study [6], the effects of hindbrain MC3/4R blockade on HR and food intake regulation were pronounced and similar in both normotensive WKY rats and SHRs, resulting in significant bradycardia concomitant with an almost doubling of food consumption and significant weight gain. These findings provide further support for the concept that hindbrain MC3/4R plays an important role in regulating food intake and may be essential for weight gain to cause elevations in HR and BP. Thus, the CNS melanocortin system appears to be a key link between weight gain, increased sympathetic activity, and hypertension, although hindbrain MC3/4R activation does not appear to play a major role in contributing to increased BP in SHRs. Also our previous studies support an important participation of brain MC3/4R in regulating BP in other nonobese models of hypertension. For instance, chronic infusion of MC3/4R antagonist into the lateral ventricles caused marked BP reductions after blockade of nitric oxide synthesis in L-NAME-treated rats, suggesting that endogenous brain MC3/4R activation may play an important role in regulating BP in this model of hypertension [7].

Activation of melanocortin pathway also seems to modulate BP responses to acute stress. Individuals with MC4R mutations exhibit reduced muscle SNS activity and impaired SNS response to inspiratory hypoxia [4,16]. In addition, we showed that MC4R in the PVN or in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) participate in the modulation of BP response to acute air-jet stress in mice [17], indicating that hindbrain MC4R modulates sympathetic responses to stress.

The notion of differential impact of the melanocortin system according to its location in the CNS is supported by previous studies demonstrating that rescue of MC4R in the PVN and a few scattered cells of the amygdala attenuated weight gain by 60% compared to MC4R-deficient mice, and this attenuated weight gain was caused by reduced food intake rather than increased energy expenditure in these mice [8]. We showed that rescue of MC4R only in POMC neurons reduced body weight, visceral adiposity, and improved glucose tolerance mainly by increasing energy expenditure, whereas appetite remained mostly unchanged [9]. Here, we show that endogenous hindbrain MC3/4R activity is also important for body weight regulation as evidenced by marked hyperphagia evoked by MC3/4R blockade. Thus, MC3/4R in different areas of the forebrain and hindbrain play a key role in regulating energy balance and body weight not only by affecting appetite but also energy expenditure. The effects of MC3/4R on these two determinants of body weight are highly dependent on the location of the MC4R in the CNS.

Chronic MC3/4R antagonism in the hindbrain also caused significant increase in plasma leptin and insulin levels that paralleled the degree of hyperphagia and weight gain in WKY rats and SHRs. Acute studies suggest that the CNS melanocortin system may also modulate insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake by peripheral tissues independent of its effects on appetite and body weight regulation [1,18–20]. However, in a previous study, we showed that restraining the hyperphagia and weight gain caused by chronic MC3/4R blockade completely prevented the hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance associated with MC4R inhibition [18], suggesting that the majority of the chronic effects of MC4R blockade on insulin sensitivity and glucose regulation in WKY rats and SHRs are likely due to hyperphagia and weight gain.

Overall, our results demonstrate that MC3/4R located in the hindbrain exert differential control on appetite, HR, and BP regulation. Endogenous hindbrain MC3/4R activity is important for appetite and HR regulation, but does not play a major role in mediating the elevated BP in SHRs. Since our previous studies found that chronic infusion of MC4R antagonist into the lateral ventricles caused marked reductions in BP in SHRs, these observations suggest that forebrain MC4R activation may play a more important role than hindbrain MC3/4R in this model of spontaneous hypertension. Unraveling the mechanisms responsible for this differential regulation of appetite, HR and BP by the CNS melanocortin system will advance our knowledge on how the brain regulates metabolic and cardiovascular functions and may pave the way to novel therapeutic approaches to treat obesity and other metabolic disorders.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant PO1HL-51971, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM104357) and by an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant to Jussara M. do Carmo.

Abbreviations

- BP

blood pressure

- HR

heart rate

- ICV

intracerebroventricular cannula

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MC4R

melanocortin-4 receptors

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rat

- SHU-9119

MC4R antagonist

- WKY

Wystar–Kyoto

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fan W, Dinulescu DM, Butler AA, Zhou J, Marks DL, Cone RD. The central melanocortin system can directly regulate serum insulin levels. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3072–3079. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.9.7665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagan MM, Rushing PA, Schwartz MW, Yagaloff KA, Burn P, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Role of the CNS melanocortin system in the response to overfeeding. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2362–2367. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02362.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huszar D, Lynch CA, Fairchild-Huntress V, Dunmore JH, Fang Q, Berkemeier LR, et al. Targeted disruption of the melanocortin-4 receptor results in obesity in mice. Cell. 1997;88:131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenfield JR, Miller JW, Keogh JM, Henning E, Satterwhite JH, Cameron GS, et al. Modulation of blood pressure by central melanocortinergic pathways. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:44–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tallam LS, da Silva AA, Hall JE. Melanocortin-4 receptor mediates chronic cardiovascular and metabolic actions of leptin. Hypertension. 2006;48:58–64. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000227966.36744.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Kanyicska B, Dubinion J, Brandon E, Hall JE. Endogenous melanocortin system activity contributes to the elevated arterial pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2008;51:884–890. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.100636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Dubinion JH, Bassi M, Mokwtarpouriani K, Hamza SM, Hall JE. Chronic central nervous system MC3/4R blockade attenuates hypertension induced by nitric oxide synthase inhibition but not angiotensin II infusion. Hypertension. 2014;65:171–177. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balthasar N, Dalgaard LT, Lee CE, Yu J, Funahashi H, Williams T, et al. Divergence of melanocortin pathways in the control of food intake and energy expenditure. Cell. 2005;123:493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Rushing JS, Pace B, Hall JE. Differential control of metabolic and cardiovascular functions by melanocortin-4 receptors in proopiomelanocortin neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R359–R368. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00518.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.do Carmo JM, Hall JE, da Silva AA. Chronic central leptin infusion restores cardiac sympathetic-vagal balance and baroreflex sensitivity in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1974–H1981. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00265.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valenti VE, De Abreu LC, Sato MA, Saldiva PH, Fonseca FL, Giannocco G, et al. Central N-acetylcysteine effects on baroreflex in juvenile spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Integr Neurosci. 2011;10:161–176. doi: 10.1142/S0219635211002671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunbar JC, Lu H. Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) products in the central regulation of sympathetic and cardiovascular dynamics: studies on melanocortin and opioid interactions. Peptides. 2000;21:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes WG, Morgan DA, Djalali A, Sivitz WI, Mark AL. Interactions between the melanocortin system and leptin in control of sympathetic nerve traffic. Hypertension. 1999;33:542–547. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahmouni K, Haynes WG, Morgan DA, Mark AL. Role of melanocortin-4 receptors in mediating renal sympathoactivation to leptin and insulin. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5998–6004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-14-05998.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo JJ, da Silva AA, Tallam LS, Hall JE. Role of adrenergic activity in pressor responses to chronic melanocortin receptor activation. Hypertension. 2004;43:370–375. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000111836.54204.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenfield JR. Melanocortin signalling and the regulation of blood pressure in human obesity. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:186–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.do Carmo JM, Sessums P, Ebaady S, Freeman J, Hall JE, da Silva AA. Melanocortin-4 receptors in the PVN and RVLM are important in mediating the cardiovascular responses to acute stress [Abstract] FASEB J. 2014;S28:686.7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo JJ, Silva AA, Hall JE. Hypothalamic melanocortin receptors and chronic regulation of arterial pressure and renal function. Hypertension. 2003;41:768–774. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000048194.97428.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li G, Mobbs CV, Scarpace PJ. Central pro-opiomelanocortin gene delivery results in hypophagia, reduced visceral adiposity, and improved insulin sensitivity in genetically obese Zucker rats. Diabetes. 2003;52:1951–1957. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obici S, Feng Z, Tan J, Liu L, Karkanias G, Rossetti L. Central melanocortin receptors regulate insulin action. J Clin Investig. 2001;108:1079–1085. doi: 10.1172/JCI12954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]